Introduction

Several definitions have been proposed to explain the phenomenon of gender-based violence. A basic definition of gender-based violence refers to violence inflicted by men on women within or outside an intimate relationship. Lorente et al. (2000) define what they call the “syndrome of aggression against women” as the set of “aggressions suffered by women as the result of social and cultural constraints acting upon the male and female gender that place women in a position of subordination to men and are manifested in the three basic spheres of personal relations: family, workplace and social life”. According to the authors, violence functions as a mechanism of social control over women and serves to reproduce and maintain the status quo of male domination. Indeed, rates of men’s violence against women are higher in societies or groups dominated by “masculine” ideas. Moreover, cultural and often legal mandates over the rights and privileges of the husband’s role have historically legitimized men’s power and domination over women by promoting their economic dependence, thus justifying men’s use of violence and coercive control over. For this reason, when addressing violence against women, it is important to take into account factors affecting specific social groups, such as migratory experiences, acculturation and economic disadvantages, which may influence rates of violence among immigrants (Gavidia et al., 2011; Stoyanova, 2018; Toledo-Larrea and Sánchez-Rodríguez, 2018 a) . Thus, for example, Vives-Cases et al. (2014) show that, in various countries and specifically in Spain, a higher likelihood of current intimidate partner violence has been reported for immigrant women compared with nonimmigrant women; however, immigrant women do not form a homogeneous social group, and factors such as country of origin, legal or illegal administrative status, length of stay and home language may influence its likelihood. Stoyanova (2018) highlights that migrant women are of special concern given the awareness that when their migration status is dependent on that of their spouse, they might be faced with a stark choice between staying in an abusive relationship and risking being deported.

In Spain, the most important legislative changes regarding gender-based violence occurred following the passing of Organic Law 1/2004 on Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence (BOE, 2004), better known as the Ley Integral or “Integral Law”. Until that time, the Spanish system was similar to that of Latin American countries and consisted mainly of modifying the existing legislation and adopting social measures to combat gender violence (Klevens, 2007) . However, the Integral Law was the first regulatory framework to address the problem of violence against women in a comprehensive manner as it established administrative, educational and social measures and incorporated amendments to the penal code, the civil code and procedural law, thus continuing a long process of legal reforms to promote equality (Martínez, 2005) . Article 32 of the Integral Law indicates that special consideration will be given to the situation of women who, due to their personal and social circumstances, may be at greater risk of suffering gender violence or greater difficulties to access the services provided for in this Law, such as those belonging to minorities, immigrants, those in situations of social exclusion or women with disabilities.

Given the importance of the Integral Law in combating gender-based violence, in recent years numerous studies have addressed specific aspects contained in the legislation. Some authors have examined gender-based violence from the perspective of education (Ferrer et al., 2011; Okenwa-Emgwa and Strauss, 2018; Taylor, 2018) , while others have dealt with aspects related to advertising and mass media (Gurrieri et al., 2016; Magaraggia and Cherubini, 2017) or the role that health care professionals play in the prevention, detection and integral attention to women affected by gender-based violence (Bacchus et al., 2018; Djikanovic et al., 2013; Otero et al., 2018). Yet other authors have analyzed gender-based violence from the perspective of social work (Ferrer and Bosch, 2014; Piedra et al., 2018; Puigvert, 2014) or in penal and judicial settings (Lemaitre and Sandvik, 2014; Molina et al., 2013; Wilson, 2017) .

In some of the works above and in many other, the socioeconomic effects of gender-based violence on women are highlighted. For example, Santaularia et al. (2014) analyze negative health outcomes, such as chronic diseases, respiratory or gastrointestinal problems in women, that arise form prolonged stress or mental problems and impaired social functioning. Reed et al. (2015) study the association between intimate-partner violence and drug use or women's HIV risk in low-income communities in South Africa. Mukanangana et al. (2014) analyze the negative impacts of gender-based violence on women's reproductive health. Bacchus et al. (2018) show evidence of a positive association between gender-based violence and subsequent depressive symptoms, hard drug and marijuana use, alcohol consumption or sexually transmitted infections.Otero et al. (2018) explore how times of economic crisis and precariousness triggered violence against women and made women more hesitant to put an end to violent relationships. Ferrer and Bosch (2014) show that Spanish society as a whole considers intimate partner violence against women as a social problem and rejects it, but there are still some violence-supportive attitudes such as victim blaming, and also a gender gap in the consideration of this violence. Piedra et al. (2018) treat the intervention and prevention of gender-based violence from a Social Work perspective: designing campaigns in connection with the main socializing agents (family, school, mass media), specific training of professionals and the correct social approach to an already consummated case of violence. Wilson (2017) analyzes how police and judges deliberately violate existing legal provisions to prevent women from divorcing or filing charges against their husbands in cases of domestic violence in Tajikistan and Azerbaijan.

Otherwise, Section 19 of the Spanish Integral Law transferred the jurisdiction over reception facilities for victims of gender violence to the autonomous communities (political and administrative divisions established under the Spanish Constitution of 1978 to guarantee the limited autonomy of these regions). In the autonomous community of Andalusia, section 44 of Law 13/2007 on Prevention Measures and Comprehensive Protection against Gender Violence (BOJA, 2007) established three levels for the care and comprehensive assistance of victims of gender violence: short-term crisis centers, shelters and transitional housing (BOJA, 2007; BOJA 2009; BOJA, 2011).

Several studies have examined gender-based violence specifically in Andalusia using official data from the Information System of the Andalusian Women’s Institute (SIAM) (see, for example, Alconada de los Santos, 2011; Agraz and Salido, 2017; Rueda, 2008; Ruiz and Rueda, 2008; Toledo-Larrea and Sánchez-Rodríguez, 2018 b) . SIAM contains data gathered from standardized questionnaires administered to women upon admission to a shelter, which include information about the general characteristics of immigrant users of Andalusian these facilities. However, the data used in the framework of this research were collected directly from women’s shelters in the eight provinces of Andalusia and include information that allow for a more comprehensive statistical analysis of the abuse suffered by immigrant women and their economic and personal achievements following a stay in a shelter. The study spans the period 2004-2010 because, as mentioned above, the most significant legislative reforms to protect women victims of gender violence were undertaken during this time. In addition, immigrant users were chosen because significant amendments were made to Organic Law 4/2000 (BOE, 2000) on the Rights and Freedoms of Immigrants in Spain and their Social Integration in this period under Organic Law 2/2009 of 11 December 2009 (BOE, 2000; BOE, 2009; Jover et al., 2010) . Specifically, Article 31bis of the modified organic law sets out that special consideration shall be given to the situation of immigrant women who, because of their personal and social circumstances, may be at greater risk of gender-based violence or face greater difficulties in accessing the services available to them. A more in-depth analysis regarding the sociodemographic profiles of foreign resident in Andalusia can be found in Vargas and Ocaña (2014) and, specifically about women, in Castillo and Ruiz (2010) or Gómez and Carvajal (2014) .

This paper is structured as follows. Women’s shelters for victims of gender-based violence in Andalusia are described in the following section. Subsequently, a statistical analysis is performed to analyze the profile and achievements of immigrant users of women’s shelters in Andalusia. In this section, data and variables are described at the beginning and, then, the statistical analysis is structured into three phases: general characteristic of these women, gender-based violence and socioeconomic achievements. The discussion and conclusions are presented in the final section.

Women’s shelters in Andalusia

As mentioned above, assistance is provided at three levels in the autonomous community of Andalusia: short-term crisis centers, shelters and transitional housing (BOJA, 2007; BOJA, 2009; BOJA, 2011). In principle, the purpose of these facilities is to provide protection and shelter to women victims of gender violence who have fled their homes and do not have family support. The staff (director, social worker, lawyer, psychologist and social assistants) provides social, psychological and legal assistance to aid the victims to live a violence-free life.

Prior to being admitted to a shelter, both national and immigrant women must fulfill the same requirements: they must have reported the abuse to the police and be unable to return home. Access to second-level facilities also requires that the victims voluntarily decide to enter the shelter and have no family or friends to provide them support. Moreover, they are required to have filed a police report and initiated criminal proceedings against the perpetrator. Women are admitted to the shelters following an assessment of their situation by the staff. Sometimes victims will seek alternative arrangements such as living with a family member or friends. At other times they may return to their abusers even when a protection or expulsion order has been issued. When a woman does decide to enter a shelter, numerous factors must be considered prior to admittance, such as the lack of family support, lack of economic independence and, ultimately, the victim’s commitment to changing the situation.

While in the shelters, women are provided with information and counseling to offer them a new perspective on life and enjoy the rights granted to all citizens in Spain under law. To achieve this aim, the programs focus on improving their self-esteem, habits and social and job skills through training schemes. The shelters also organize support groups to allow the women to talk about their experience, promote nonviolent and peaceful coexistence and acquire new role models. Labor market integration as well as improving access to social, educational and training resources are also key objectives of these programs.

When legal measures do not guarantee the safety of victims, other measures are taken, such as temporary shelters to cover the basic needs of female victims and their children. These measures are especially important in cases where the victim lacks financial resources and/or family and social support. These resources are particularly helpful to aid especially vulnerable women who lack the necessary social skills to undergo the path to recovery.

Nonetheless, despite the measures taken, some victims of gender-based violence, such as substance abusers, women with mental health issues or those working in the sex industry, require specialized assistance that cannot be provided in the shelters as they are not sufficiently equipped to address such specific needs. Moreover, the behavior of these women may interfere with the day-to-day functioning and objectives of the centers.

It should be noted that 50% of victims of gender-based violence admitted to a shelter suffer problems directly associated with this type of violence but may also have other related issues such as dysfunctional families, lack of effective support networks, economic deprivation, precarious housing, dependence on social services or little or no work experience. In addition to suffer abuse, when these women enter a shelter they must abandon their immediate environment and start the recovery process, that is, they must deal with their pain without the emotional support of their family and friends, which for many makes the road to recovery even more difficult.

Immigrant users of women’s shelters in Andalusia: statistical analysis

In the following section, statistical analyses are performed to ascertain the profile of immigrant victims of gender violence who were admitted to a shelter in one of the eight provinces of Andalusia and study the evolution and socioeconomic changes experienced by these women over their stay.

Data

The data were gathered from a standardized questionnaire women are required to fill out upon admission to a shelter in any of the eight Andalusian provinces. Part of the data has been collected and analyzed by SIAM since 2007 and published in official reports of the Andalusian Women’s Institute (IAM) (Sibony, 2010) .

However, we also examine other data from the questionnaire that are not available in the SIAM database and have therefore not yet been subject to statistical analysis, such as information on the violence suffered by these women and how their situation has changed after leaving the shelters.

To obtain more reliable results, selection and sampling procedures have not been used, but the statistical analysis considers the entire population (i.e., all immigrant women admitted to a shelter in any of the eight Andalusian provinces from 2004 to 2010). The results obtained can be extrapolated to other more general geographical contexts.

As mentioned above, the period 2004-2010 was selected due to the significant legislative reforms relating to gender-based violence made during this period in the framework of the Integral Law. In addition, important modifications were made to the law on immigration (Organic Law 4/2000); a fact which prompted us to focus on immigrant users of Andalusian women’s shelters. This immigration law means important advances in the recognition of rights, an increase in legal security, progress in social benefits and some changes in the regulation of residence and work permits and therefore, opens up the possibilities of social integration of immigrants.1 Thus, while the Integral Law has had a positive effect on all female victims of gender violence, such effect has been even more pronounced on the personal, social and economic situation of immigrant women following the legal reform.

Variables

The data used for the statistical analysis were aggregated by year and province. The observed statistical variables were as follows:

Year of admission to the shelter

Province: Almeria, Cadiz, Cordoba, Huelva, Jaen, Malaga and Seville

Number of women admitted to shelters by province and year

Number of immigrant women admitted to shelters by province and year

For immigrant women, the following additional information was also considered:

Marital status: married, separated/divorced or unmarried

Number of children: only those admitted to the shelter

Educational level: no schooling, primary schooling, secondary education, higher education

Employment: number of women with work-based training who were employed when leaving the shelter and number of women who worked in the underground economy, the service sector, as migrant farmworkers or who had never been employed

Reason for immigrating to Spain: economic or family reunification

Administrative situation: number of regulatory procedures and residence permits2

Number of cases associated with abuse or derived abuse and cases with family support3

Number of reports filed, restraining or protection orders issued and civil proceedings undertaken against the perpetrator (divorce, parent-child measures, guardianship and custody proceedings)4

Number of women receiving public financial assistance (as set out in Chapter IV of the Integral Law)

Residence after leaving the shelter: transitional housing, independent residence, family residence, return to the abuser, conjugal residence without the abuser, residence with friends, other women’s shelter, other type of shelter

Methodology

The statistical analysis is structured into three phases:

Phase I: General characteristics. In a first phase, the variables age, marital status, number of children, educational level, previous occupations and reason for immigrating to Spain were analyzed with regard to the immigrant women in the shelters.

Phase II: Analysis of gender-based violence. In this phase, information was collected on whether the women had a history associated with abuse or derived abuse or received family support.

Phase III: Analysis of the evolution and achievements of women in the shelters. We first analyzed if the women had initiated a criminal proceeding, obtained a protection order or initiated a civil proceeding against their perpetrators during their stay in the shelter (i.e., married women requesting a divorce; unmarried women requesting parent-child measures or child custody or guardianship proceedings), as well as the number of regulatory procedures and residence permits. We also analyzed if the women were employed, had received public financial assistance and their place of residence after leaving the shelter.

The statistical analysis for the three phases includes graphical procedures, such as (simple or clustered) pies, line and bar charts and histograms. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the strength of the linear relationship between two numerical variables. This coefficient takes values between -1 and 1. A positive sign of the coefficient indicates that the two variables increase or decrease at the same time. In the event that the increase of one variable involves the decrease of another and vice versa, the sign of the coefficient is negative. The closer of the absolute value of the coefficient is to the value of 1, the stronger the linear relationship between the variables. However, if the coefficient is close to 0, the linear relationship is almost non-existent. In order to statistically test the significance of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, a hypothesis test is performed. The null hypothesis of the test is defined as the equality to zero of the coefficient, such that the linear relationship between the variables is higher as the limit probability (p-value) approaches zero.

Besides, a correspondence analysis is applied to obtain further information about the relationship structure existing between the different categories of two qualitative variables. The application of the technique entails designing a Cartesian diagram in two orthogonal dimensions, which represents the different modalities for both variables. The degree of relation between two categories is higher as their proximity increases in the representation. Moreover, categories with high scores, in absolute terms, in an axis or dimension allow discriminating between categories and therefore giving interpretation to such axis.

Results

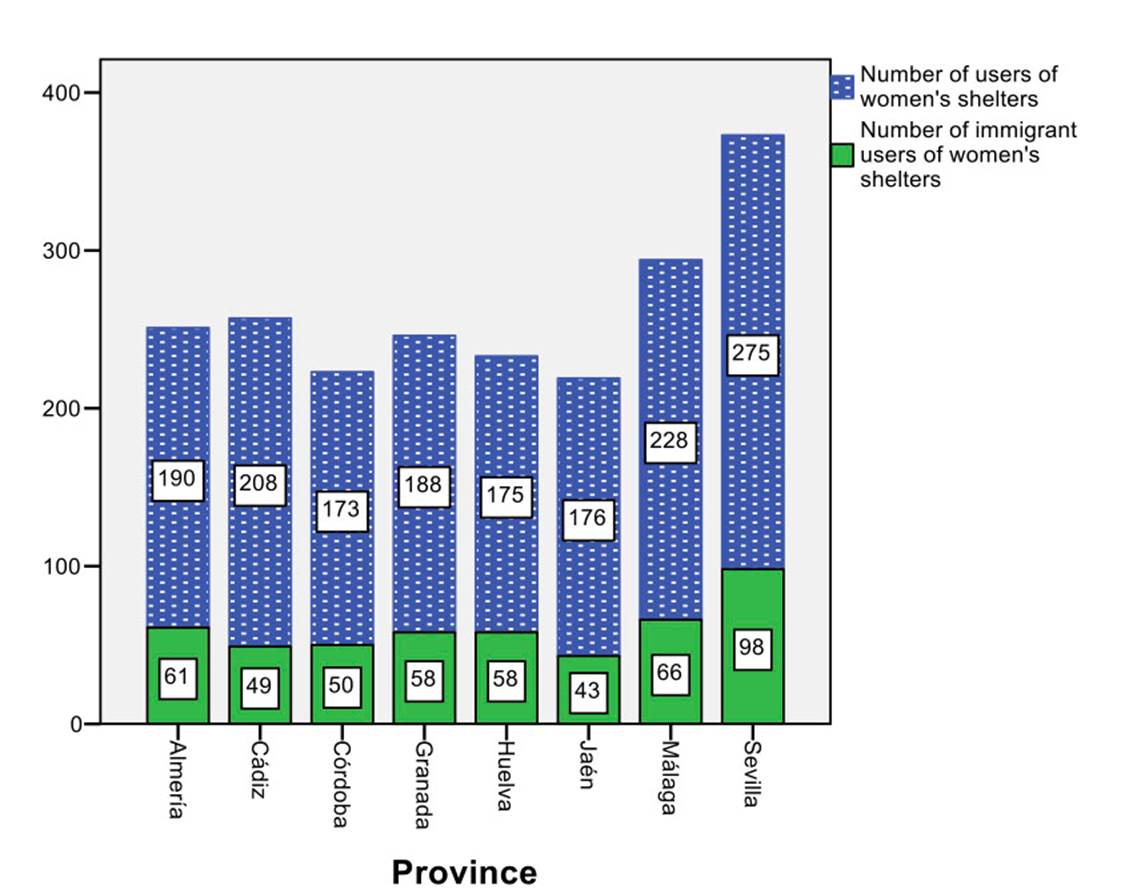

Data on 1613 women admitted to shelters in Andalusia were collected; 483 of these women were immigrant. Figures 1 and 25 show the distribution of the total number of women (both Spanish and immigrants) and the total number of immigrant women admitted to shelters over the period 2004-2010. The distribution of frequencies is grouped by provinces (Figure 1) and years (Figure 2). Figure 1 highlights that Seville is the province with the largest number of admissions to shelters (275), followed by Malaga and Cadiz. Seville is also the province with the largest number of immigrant women (98) admitted to shelters, accounting for 4.68% of all women in shelters, followed by Malaga with 66, which represents 3.15% of the total. Figure 2 shows the distribution of admissions by year. Then, in Figure 2, 2004, 2005 and 2010 show the highest admission rates, with 291, 259 and 244 women admitted to shelters in each of these years, respectively. However, the highest percentage of immigrant women (4.06%; 85) corresponds to the year 2009.

Since this study focuses specifically on female immigrants admitted to women’s shelters in Andalusia, the following statistical analysis considered only the 483 immigrant women included in the database (29.94% of a total of 1613 women).

Phase I. General characteristics of immigrant users of women’s shelters

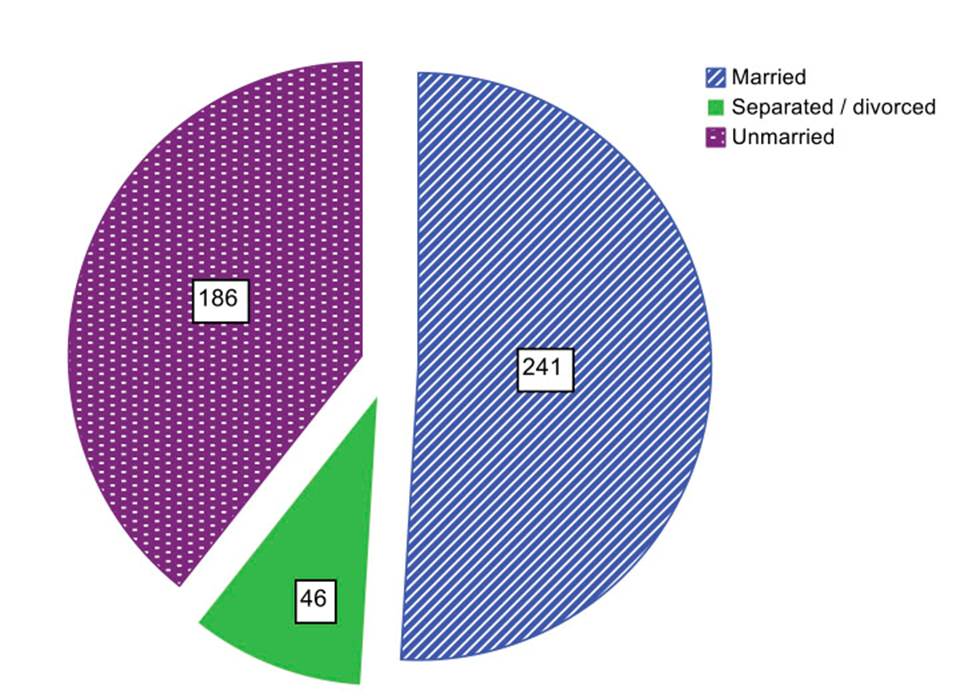

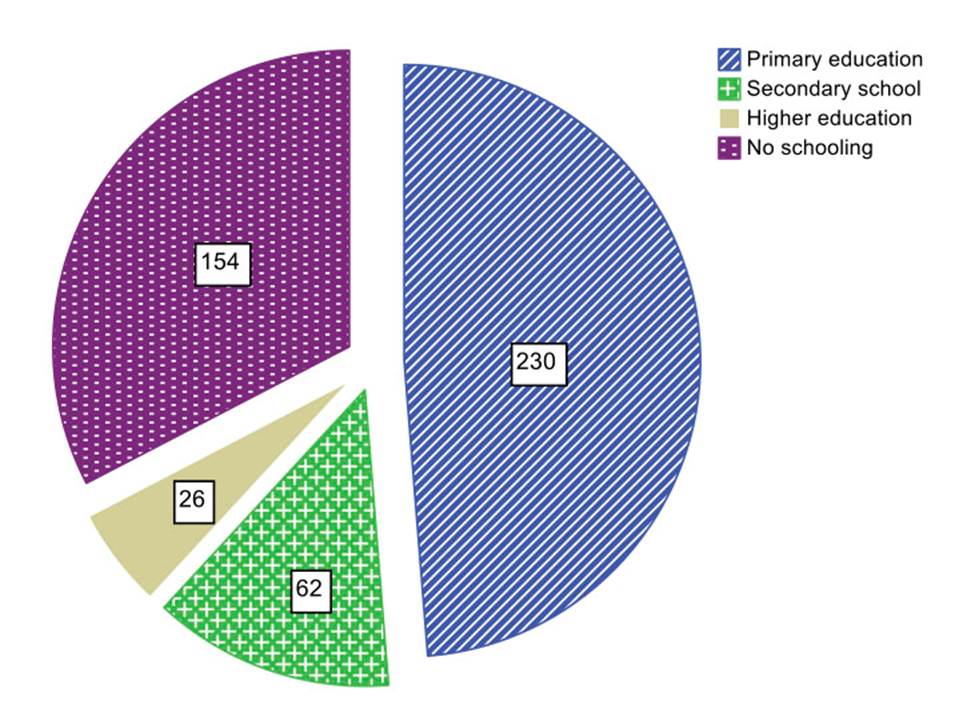

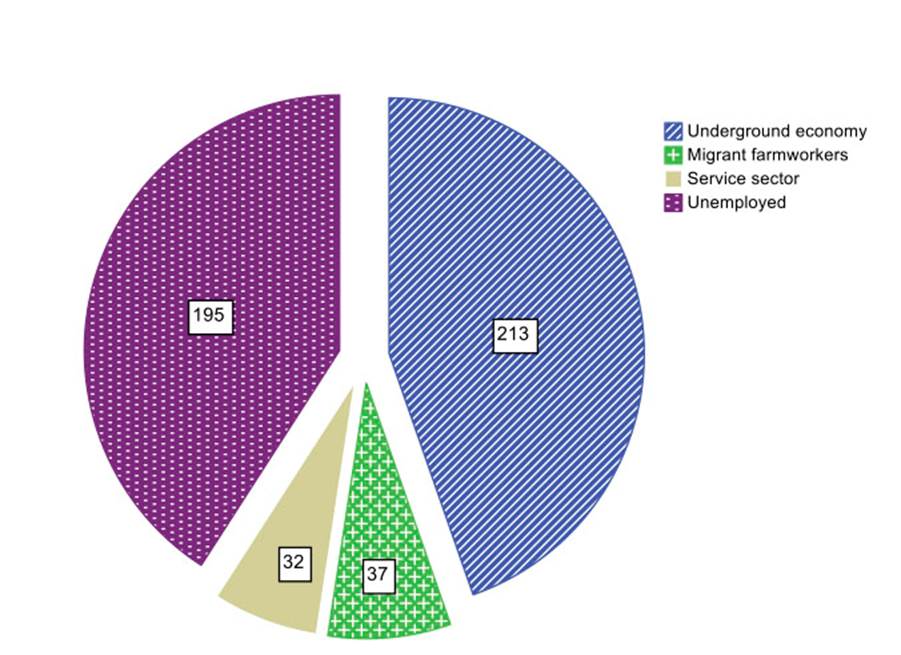

The mean age of the immigrant women admitted to the shelters was 31.03 years and the mean number of children per woman was 1.09 (Table 1). As shown in figures 3 and 4, respectively, most of the women were married (241) and had primary schooling (230). Figure 5 also shows the distribution of the women’s occupations. The underground economy was the first source of income for 213 (44.10%) of the women and 195 (40.37%) were unemployed. As regards the main reason for immigrating to Spain, 325 of the women immigrated for economic reasons and 158 for purposes of family reunification (Figure 6).

Phase II. Analysis of gender-based violence

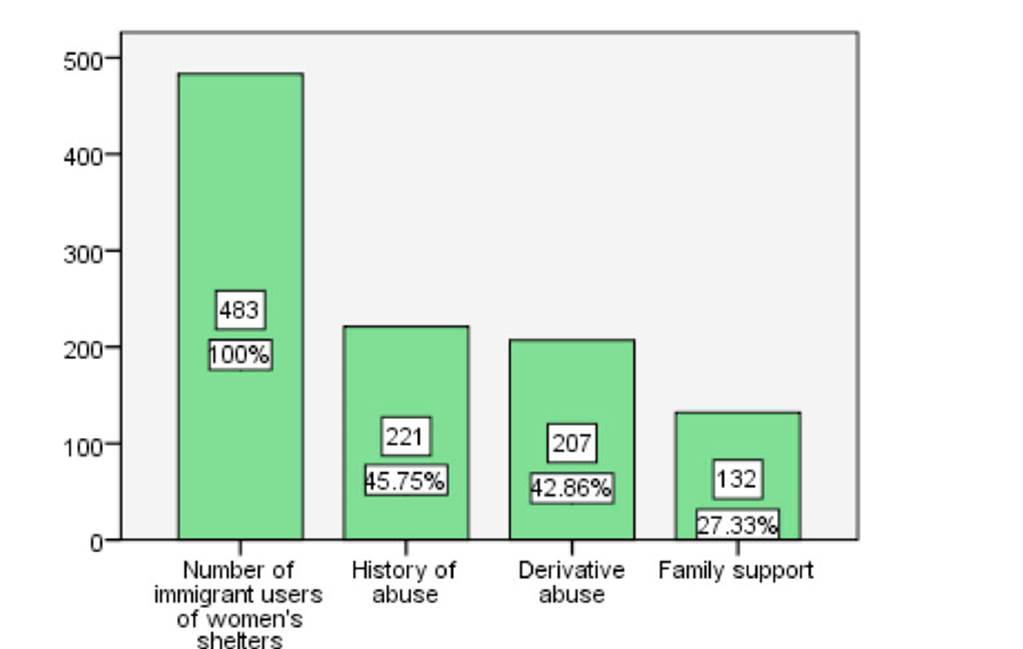

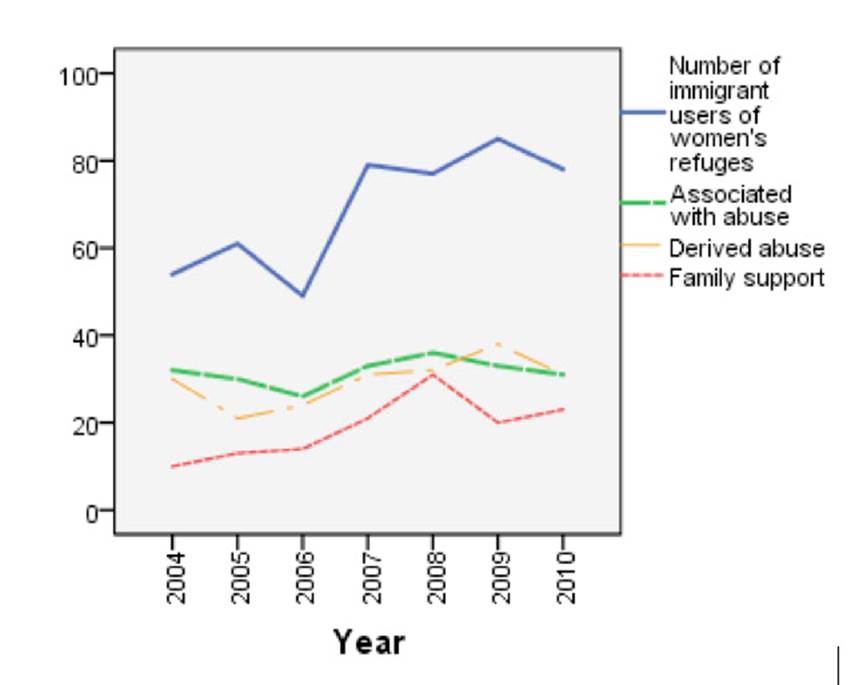

Figure 7 shows that, of the 478 immigrants admitted to the shelters, 45.75% had a history associated with abuse, 42.86% had derived abuse and only 27.33% received family support. The distribution of these three variables is shown in Figures 8 and 9 by province and year, respectively. Figure 8 again shows that Seville is the province with the highest absolute values for the three variables considered. Moreover, it is the only province with an equal or even slightly higher number of women who receive family support and women with a history associated with abuse or derived abuse. As regards the distribution by years, all the variables show an upward trend except for family support, which decreases slightly in 2009 and 2010.

Finally, Table 2 shows the results of Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the variables used to analyze gender-based violence. The three coefficients are statistically different from zero, with the strongest linear relationship observed between a history associated with abuse and derived abuse and another associated with abuse and family support.

Phase III. Analysis of the evolution and achievements of immigrant women in the shelters

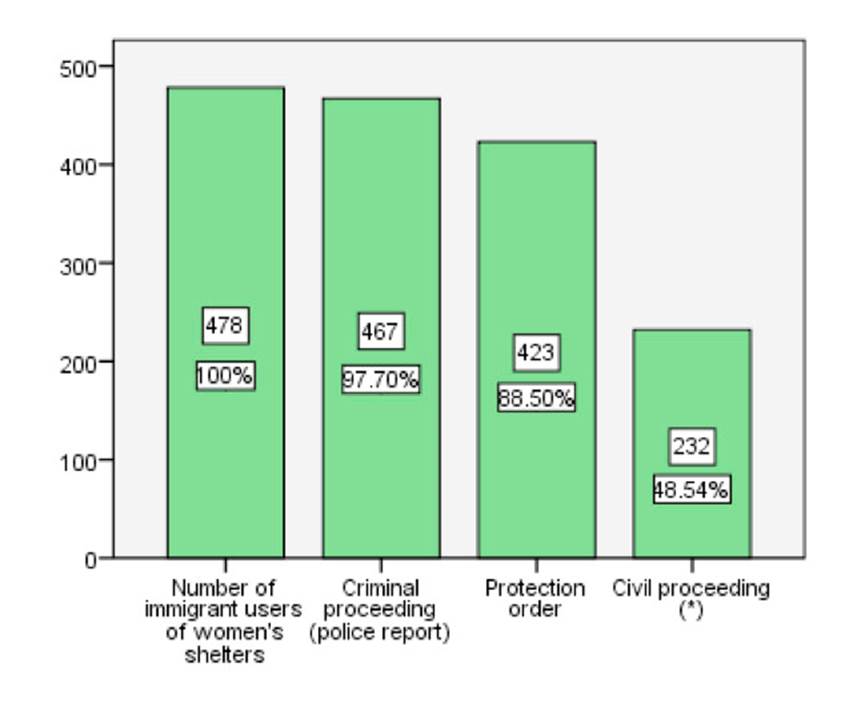

With regard to the criminal and civil proceedings initiated by the immigrants during their stay in the shelter, Figure 10 shows that of the 478 women studied, almost all (467; 97.70%) filed a police report against the perpetrator. A high percentage of women (88.50%) also obtained a protection order. However, the percentage falls to 48.54% (232) for married women who initiated divorce proceedings and unmarried women who requested parent and child measures or initiated guardianship and custody proceedings.

Figures 11 and 12 compare the number of immigrant women who were employed after leaving the shelter and the number of immigrant women with work-based training by province and year, respectively. The figures show that both distributions are clearly related. This is confirmed by Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient (Table 3), which shows a value of 0.612 with a sufficiently small p-value (less than 0.01). Therefore, it can be concluded that it is easier for women with worked-based training to find a job.

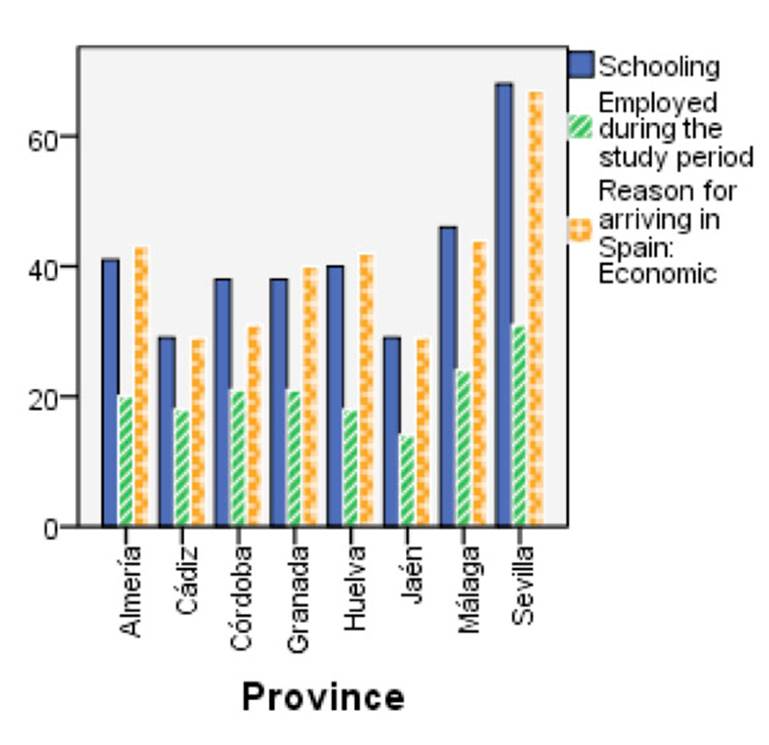

Figures 13 and 14 show three variables which, a priori, might be related: the number of women with schooling at any level (primary, secondary or higher education), the number of women who were employed after leaving the shelter and the number of women who immigrated to Spain mainly for economic reasons. These data are grouped by province (Figure 13). As it is seen, the variables exhibit a similar trend, indicating thus a linear relation between them. However, in Figure 14, which includes data for each year, the trend is not as clear. In this case, the number of women who found employment after leaving the shelter remains, on average, constant over the period 2004-2010, the number of women who immigrated to Spain for economic reasons increases and the number of women with schooling decreases in 2010.

Table 4 displays Pearson’s pairwise correlation coefficients between the three variables considered in figures 13 and 14, without differentiating between province and year. The coefficients indicate the existence of a positive linear relationship, which is statistically significant at a 0.01 level in the three cases.

Figures 15 and 16 show the distribution of women who received public financial assistance after leaving the shelter by province and year. In absolute terms, Seville is the province with the largest number of women receiving aid (this is the province with the most inhabitants and the one with the largest number of immigrant users of women’s shelters), followed by Malaga and Almeria. As for the years, 2009 shows the highest number of users of women’s shelters and women who received public financial assistance, followed by 2007. In total, 214 of the 483 immigrant women in shelters (44.30%) received financial assistance during the study period.

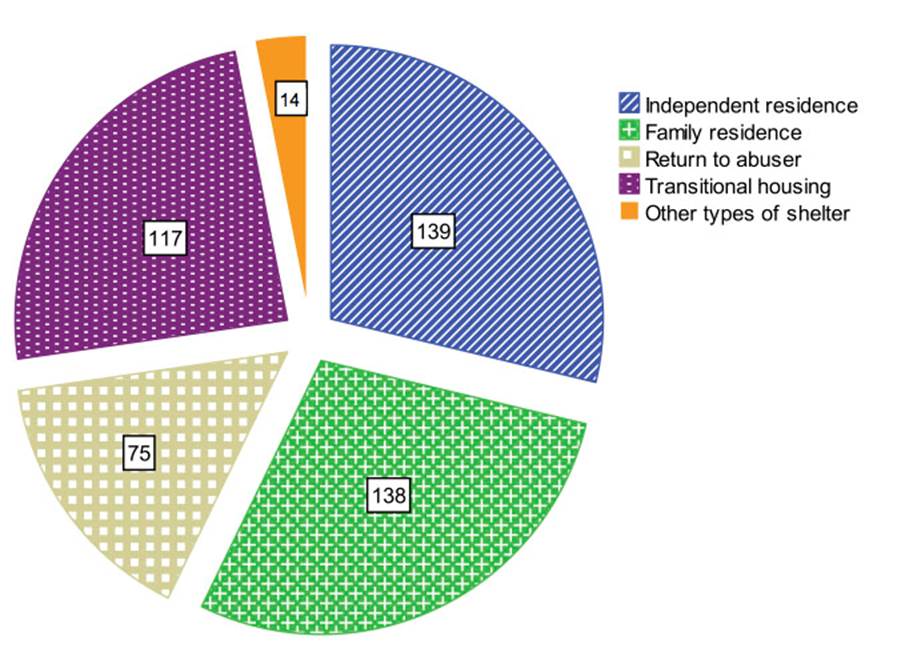

Figure 17 shows the distribution of place of residence after leaving the shelter. The largest percentage of women (139; 28.78%) moved to an independent residence, followed by 28.57% (138), who went to the family home. The percentage of women who returned to their abuser is 15.53% (75).

In order to determine whether receiving public financial assistance influences choice of residence after leaving the shelter, Pearson’s linear correlation coefficients were calculated. As can be seen in Table 5, there are significant linear relationships (at the 0.01 level) between the number of women receiving public financial assistance and the number of women living in an independent residence, a family residence or in transitional housing. The linear relationship is significant at the 0.05 level with the number of women living in other types of shelters. However, the linear relationship is practically non-existent between the number of women with financial support and the number of women who return to their abusers.

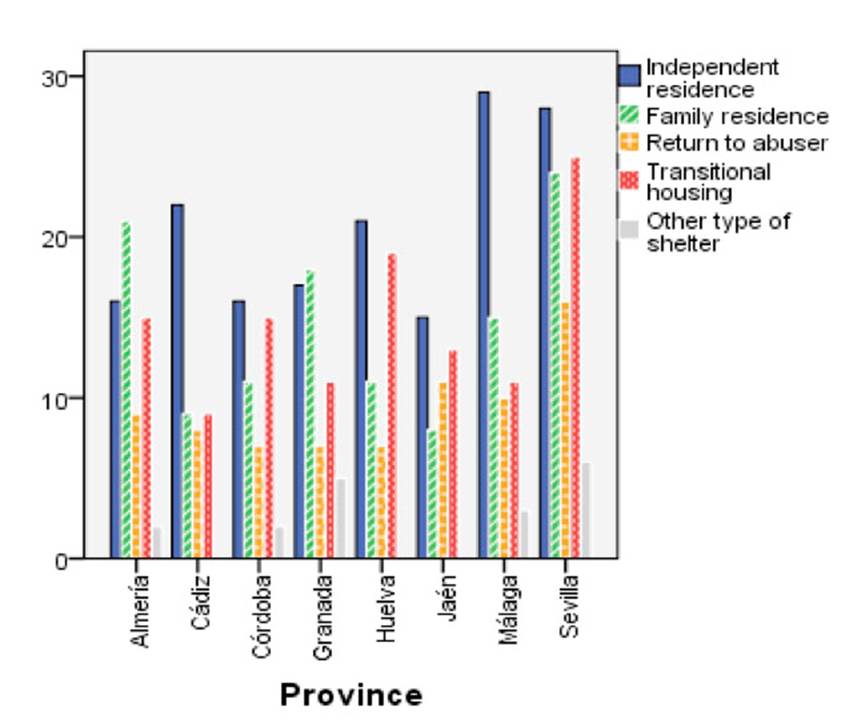

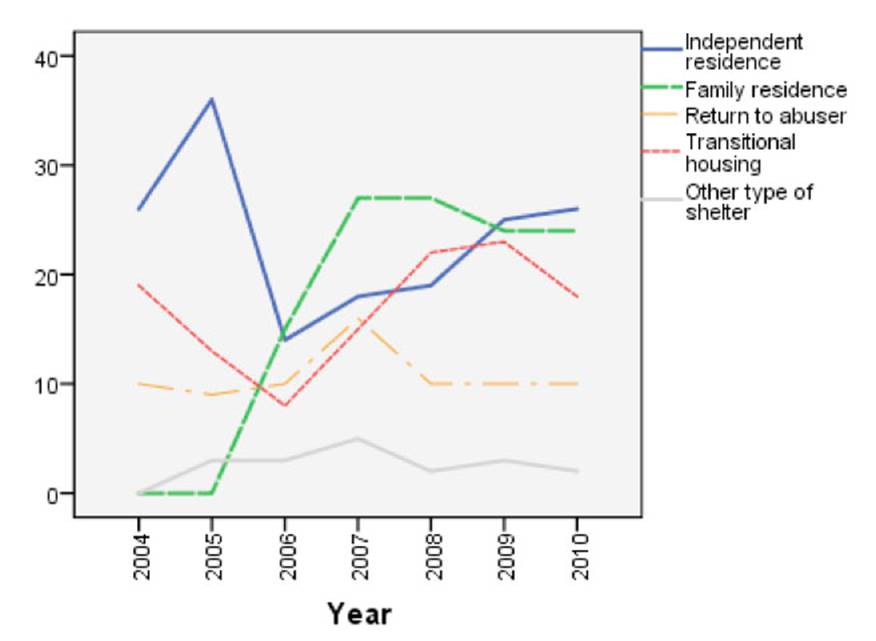

Figures 18 and 19 present the distribution of residences after leaving the shelter by province and year. As can be seen, in Almería, Granada and Sevilla, the majority of immigrant women moved to a family home, while most of those in Cadiz and Malaga chose to move to an independent residence (Figure 18). The number of immigrant women who returned to their abusers is shown in the center of the graph, and is considerably higher than the number of women who moved to another type of shelter. Figure 19 shows that, in 2007, most of the women moved to a family home, while in 2005, 2009 and 2010, the majority of them chose to move to an independent residence. Moreover, in 2007 there was a slight increase in the number of women who returned to their abusers after leaving the shelter.

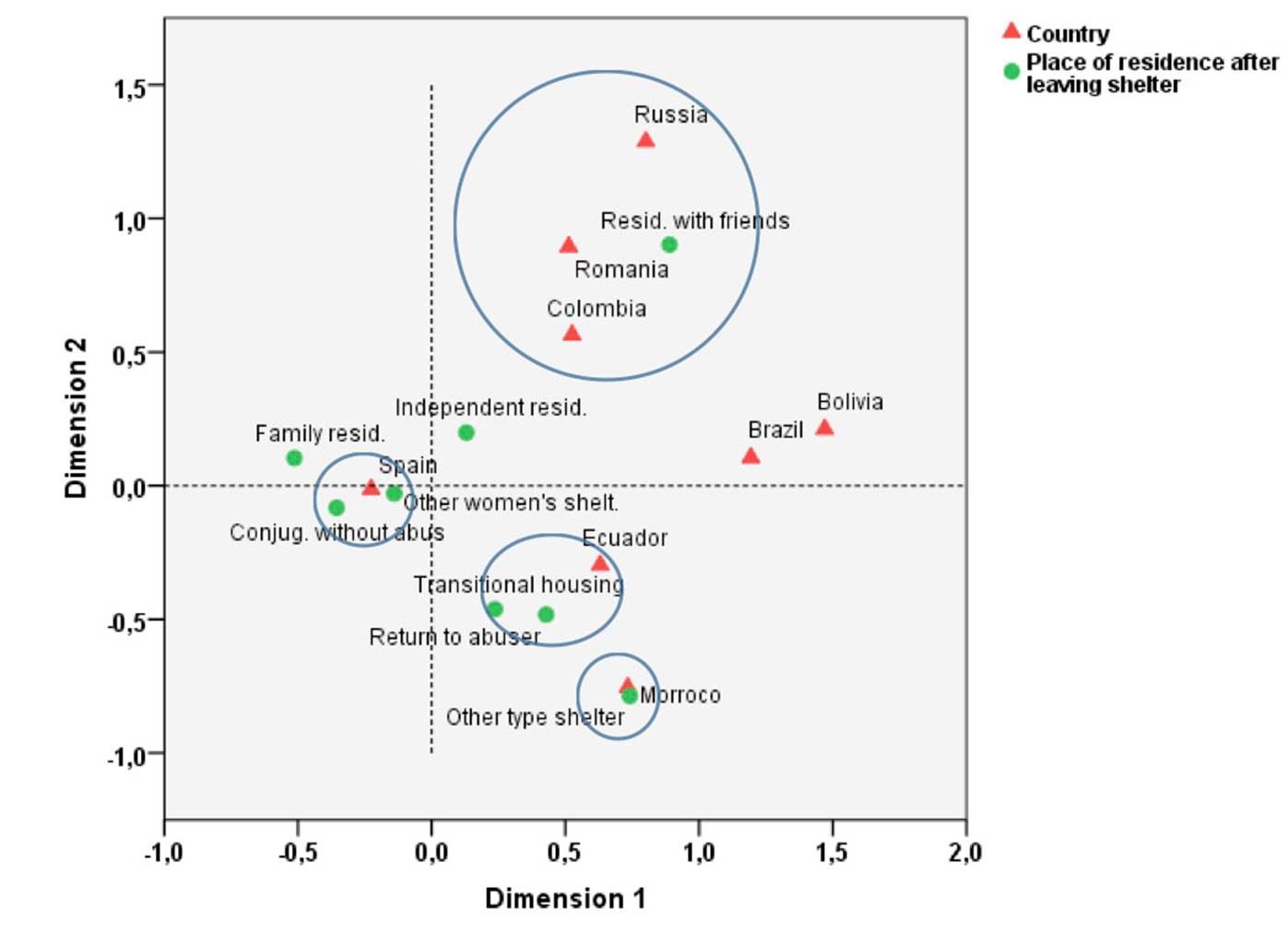

Finally, the aim is to apply a correspondence analysis to get further information about the relationship structure existing between the different categories of the following variables: country and place of residence after leaving shelter, and so to investigate if Spanish and immigrant women have similar behavior patterns. Firstly, Dimension 1 of Figure 20 discriminates among the behavior of Spanish women and those of other nationalities after leaving the women’s shelter. Secondly, taking into account the proximity between categories, the following conclusions can be obtained about the place where they usually move: a) Spanish women often go to their conjugal home without the abuser or another women’s shelter; b) women who come from Russia, Romania or Colombia usually move to a residence with friends after leaving the shelter; c) Moroccan women tend to move to another type of shelter; d) Brazilian and Bolivian women are not associated with a particular type of residence; finally, e) Ecuadorian women show the greatest tendency to return with her abuser.

Discussion and conclusion

Countries around the world have implemented important administrative, educational and social measures and modified their respective penal codes, civil codes and procedural law to combat gender-based violence against women. The measures taken to provide comprehensive social assistance include housing facilities and protection for victims of gender-based violence at risk who have been forced to flee their homes because they fear for their own life or safety or that of their children (Hester et al., 2007) . Although the purpose of these facilities is similar, they differ depending on the country and the social, cultural and religious setting in which they operate. In Spain, we find that shelters set up exclusively for women victims of gender-based violence and their children reflect society’s commitment to the victims and are conducive to the full integration of women and their children in Spanish society, with all the rights pertaining to them under law (Marrades and Serra, 2013; Sibony, 2010; Stoyanova, 2018) .

A statistical analysis was performed using data on immigrant users of Andalusian women’s shelters collected in the framework of a research project, as well as official data of the SIAM database. Official sources allow determining the general characteristics of these women: their mean age is about 33, they have only one child who also entered the shelter, most are married and have only primary studies, the underground economy is their main source of income and they have immigrated to Spain primarily for economic reasons. However, the data we collected permitted us to perform a more exhaustive analysis on the violence these women have suffered and the achievements they made after leaving the shelter. Based on our own data, we are able to draw the following conclusions.

Firstly, as regards abuse, a high percentage of immigrant women admitted to shelters have a family history of abuse and are derivative victims of abuse, with a high positive linear correlation between both variables. Moreover, the majority of these women filed police reports and obtained protection orders against the perpetrators, while approximately half initiated civil proceedings: parent and child measures or guardianship and custody proceedings in the case of single women and divorce proceedings in the case of married women (Nikparvar, 2018; Sabido, 2013) . Second, having a job, schooling and/or work-based training and immigrating to Spain mainly for economic reasons are also variables with a high positive linear correlation. Importantly, the economic resources of these women after leaving the shelter is a significant factor in their decision to return to the abuser as women who receive public financial assistance (around 50%) are more likely to move to an independent or family residence, transitional housing or another type of shelter rather than return to the abuser. Finally, the behaviour patterns about the residence after leaving the shelter are related to each women's original country.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)