Introduction1

The XX century media further solidified the false association between mass culture and women pre-dating modern era (Huyssen, 2006: 94 ), sparkling in scholars a certain disregard toward television. Heightening academic interest in gender representation of women in television can be attributed to the rise of TV fiction in the late 1990’s and its popularity among feminine audience, after the impulse of feminist studies of soap operas in the 1980’s (Brunsdon, 2000). Stemming from the overrepresentation of sex on television (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012; Kunkel et al., 2005) and the debate on “new femininities” (Gill and Scharff, 2011), sexuality in TV fiction has become a fruitful field of study. As Plummer points out, “People increasingly have come to live their sexualities through, and with the aid of, television, press, film, and most recently, cyberspace” (Plummer, 2003: 275).

Content analyses of sex representations reinforce the idea that television fiction offers a distorted image of sexuality (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012; Fisher et al., 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005; Signorielli, 2000), which plays an important role in the construction and reinforcement of gender stereotypes (Behm-Morawitz and Mastro, 2008; Eyal and Finnerty, 2007; Lauzen et al., 2008; Merskin, 2007; Ward, 1995). On the other hand, some of the research works carried out by Signorielli and Bacue (1999), and Signorielli and Kalhenberg (2001) stress the didactic potential of television fiction in relation to sex and stereotypes, despite cultivation theory scholars tend to perceive television as a conservative medium. In general, it is considered that information on such relevant issues as abstinence, social responsibility and sexual protection constitutes a reduced part of the representations of sexuality (Berridge, 2014; Kelly, 2010; Kunkel et al., 1999; Strasburger, 2010; Ward, 1995), just like the consequences of sexual relations (Aubrey, 2004;Aubrey and Gamble, 2014;Eyal and Finnerty, 2007;Kunkel et al., 2005).

The construction of gender in Spanish television also constitutes a growing body of research. However, as in other European countries, content analysis on domestic fiction focuses mainly on young people (Guarinos, 2009; Ramajo et al., 2008; Masanet, Medina and Ferrés, 2012; Lacalle, 2013), while studies on the representation of women concentrate on the analysis of American television fiction broadcast in Spain (Chicharro, 2013; García-Muñoz and Fedele, 2011; Fernández-Morales, 2009; Trapero, 2010). In this sense, the research work presented here constitutes a novel contribution to the study of representations of female sexuality in Spanish television fiction, both in terms of its wide sample (709 female characters) and innovative method. The analysis combines the coding in SPSS of 40 variables with the description of sexuality-related storylines that include female characters.

Female sexuality and television fiction

Unlike other fields of research, the sexualization of culture is a complicated and often polarized field (Gill, 2014), in which claims on the educational potential of representations (Collins et al., 2003;Davis, 2004;Emons et al., 2010;Oliver et al., 2014; Signorielli and Kahlenberg, 2001) coexist with criticism to the growing pornographication of mainstream TV (McNair, 1996, 2002;Attwood, 2006). Representations of sexuality can play a decisive role in both the processes of socialization and learning (Collins et al., 2003;Farrar et al., 2003) on the basis of reproduction of scenarios and scripts (Brown, 2002). Therefore, representations of sexuality are important in the perceptions of sexuality and sexual behaviors among viewers (Eyal and Finnerty, 2007), especially young ones (Eyal and Finnerty, 2007;Masanet et al., 2012;Plummer, 1995).

The study of new femininities, promoted by “postfeminism” and “third-wave feminism”, has identified the agency of women with uninhibited sexuality that characterizes an increasing number of female characters in television fiction series, which assimilate empowerment with the construction of their own subjectivity. Critical feminism, on the contrary, complains about the overrepresentation of female sexuality in the media (Gill, 2008) and is concerned by the progressive consolidation of certain neoliberal sexual prototypes (Gallager, 2014;Gill, 2007), which turn femininity into a hyper-sexualized woman systematically associated with consumerism (McRobbie, 2009;Gill and Scharff, 2011). Gill (2007) understands postfeminism as an articulation of feminist and anti-feminist ideas, produced “through a grammar of individualism that fits perfectly with neoliberalism”.Gallager (2014: 26) claims that the feminist discourse in the media tends to be conservative and is largely structured upon notions of individual choice, personal empowerment and freedom.

Harris (2004) identifies two types of young women in the XXI century: the “can-do girls”, successful young women who become role models for teen and young women, and the “at-risk girls”, which represent failure. Can-do girls are often trapped between the “double entanglement” (McRobbie, 2004: 256 ) produced by the attempt to reconcile the values traditionally associated with femininity with the desire to always be sexually available for men. As a result:

young women are hailed through a discourse of ‘can-do’ girl power, yet on the other their bodies are powerfully re-inscribed as sexual objects” (Gill, 2007).

Levy (2005) uses the term “raunch culture” to refer to the hyper-sexualization of a culture that identifies female empowerment with the transformation of women into sexual objects. She also highlights the persistence of two contradictory female stereotypes used to characterize the same woman: the woman who wants to be like men in order to dominate them, and the hyper-sexualized woman who wants to appeal to men. From Braidotti’s perspective (2004) , however, it is neither about accepting nor celebrating the differences, but about learning how to live with those dissimilarities. This aligns with her determination to go beyond social criticism and identify representations that are able to transform reality (Braidotti, 2001).

Disguising the structural inequalities reflected in the prototypes of postfeminist TV portrayals (Ally McBeal,Sex and the City, Desperate housewives, etc.) leaves out women who do not fit into the current molds and promotes the representation of female sexuality according to the iconographic models of pornography (Attwood, 2006). The growing pornographication of the media —the generalized fascination with the sexualization of women and the graphic depictions of sexuality— converges with the “backlash” (Faludi, 1991) or “retro-sexism” (Whelehan, 2000) made up of ambiguous and fragmented discourses that represent a major setback in the achievements of historical feminist movements. Unfortunately, the framing of the social debate on the protection of children “prevents an examination of the potential harms to the status of women, an issue which is certainly equally worthy of discussion” (Tyler, 2010, online).

Method

The symbolic nature of television’s texts makes the context an essential element of sexuality’s representations (Kelly, 2010;Kim et al., 2007;Ward, 1995), since the media not only provide culturally-constructed mediated portrayals of sexuality, but also “suggest that events are to happen in certain contexts” (Aubrey and Gamble, 2014: 133 ). The importance of the context in the analysis of the characters’ sexuality has been underscored by numerous researchers inspired by the social learning theory (Eyal and Kunkel, 2008;Farrar et al., 2003;Kunkel et al., 2007;Rivadeneyra, 2011). From a feminist perspective, contextual variables are essential to correlate gender inequality with other types of social inequalities, as Gamman and Marshment (1989: 7) pointed out in the 1990’s, when they criticized the depoliticization made by psychoanalytic criticism of other power relations, such as class, race and generation.

The study presented here combines codification in SPSS Statistics with socio-semiotics approach to analyze the representations of female sexuality in Spanish TV fiction. Based on the contributions of other authors, who have studied the representation of sexuality in television fiction, by sexual content we mean “any depiction or portrayal of talk/behavior that involves sexuality, sexual suggestiveness and sexual activities/relationships” (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012: 333 ), including “affection that implies potential or likely sexual intimacy” (Farrar et al., 2003: 10 ).

The selection of SPSS Statistics to build the quantitative database is due to its flexibility to recode different variables and data inputs, which allows social-sciences researchers to adapt it to their needs. Socio-semiotics is a branch of structuralism semiotics, which deals with the social dimension of discourses (Landowski 1997;Semprini, 1990); but, unlike textual analysis, socio-semiotics integrates the context of the object of study into the analysis. This qualitative approach is particularly useful in the analysis of sexuality, considered to be “a hugely symbolic and semiotic affair"(Plummer, 2003: 275) for humans.

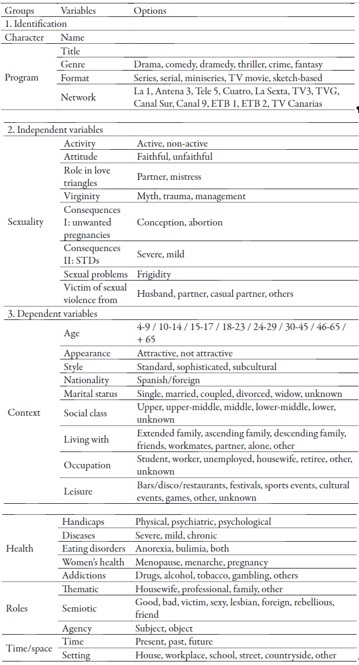

The sample consists of 709, female lead and secondary characters from all the domestically produced Spanish television fiction shows premiered by Spain’s mainstream networks in 2012 and 2013. The sample selection of the 84 programs (series, soap operas, miniseries, TV movies and sketches) excluded those occasional secondary characters that appear in three or fewer episodes. The first phase of the research included watching a sample of 3,305 episodes: 1,779 broadcast throughout 2012 and 1,526 throughout 2013. The following step was to build the code book (table 1),2 divided in eight sections: program identification, sexuality, context, character’s relevance, relationships, health, roles played and settings. The 40 variables used in the encoding comprehend eight independent variables on sexuality, 27 dependent variables and five related to the identification of the program (character’s name, program’s title, network, fiction genre and format). The independent variables on sexuality are as follows: activity, attitude, role in love triangles, virginity, unwanted consequences of sexual relations (pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases [STDs], sexual problems and sexual violence). The age of the characters was grouped into eight clusters in order to reduce the dispersion inherent to the coding of this variable: 4-9; 10-14; 15-17; 18-23; 24-29; 30-45; 46-65 and over 65. Each variable allows choosing between several options, with the exception of string variables (character’s name and program’s title).

The encoding involved thirteen researchers, competent in the use of SPSS. Of these researchers, four had PhD degrees and the rest were PhD students. Before the coding, a pilot test analysis was carried out to test the inter-coder agreement and to detect possible errors in the data inputting stage. In this way, discrepancies between coder’s assigned values led to the revision of the code book concepts, while the missing values were identified in the Case Processing Summary tables and erroneous cases were located in the database and corrected in the Data Editor. Once the inter-coder reproducibility and the quantitative database were verified, we carried out the univariate analysis, through nominal variables and frequency tables; and the bivariate analysis, which allowed us to cross examine the seven (independent) sexual variables and age with the rest of the (dependent) variables, in order to create contingency tables and proceed to the main data analysis.

The data matrix consists of 709 units of analysis (cases), one for each character included in the sample. The crossing of the seven sexuality-related variables with the 32 dependent variables produced 224 contingency tables, plus 31 tables that resulted from the crossing of the age variable with the rest of the dependent variables, which generated a total of 255 contingency tables. The quantitative database was complemented with a qualitative database, built in parallel to the coding process in SPSS. This database is comprised in the main sexuality-related storyline of each of the 360 female characters (50.8%) associated to this topic. However, since a storyline can include different sexual variables, complex storylines were separated in storylines dealing with a single sexual variable. A total of 714 storylines regarding sexuality were identified.

Contingency tables allowed us to structure the data obtained and to examine the most relevant results of variable crossing in relation to the corresponding storylines. This last stage of the study involved the participation of seven of the researchers who developed the quantitative and qualitative databases (SPSS and storylines, respectively). The adoption of a narrative content unit (storyline), instead of other technical units, such as the scene unit (Al-Sayed and Günter, 2012), was motivated by the greater thoroughness provided by the former type of unit to analyze serial narratives, as pointed out by Maura Kelly (2010: 482) in her study on the representation of virginity in television fiction.

Results

The storylines of 50.8% (N = 360) of the sample of female characters are related to the sexual sphere. The sexual activity of the female characters is directly proportional to their physical attractiveness and inversely proportional to age, with the exception of the groups of little girls (4 to 9 year-olds) and adolescent girls (10 to 14 year-olds), whose sexual dimension is hardly represented. Thus, 61.4% (N = 283) of the sexually active women are physically attractive and 82.9% (N = 63) accentuate their sex appeal through provocative attire and constant seductive attitude toward men. The most sexually active age group is 30-to-45-years, which constitutes the largest age group in the sample (42.8%; N = 154), concurring with the preferred target audience of Spanish television fiction. The second most sexually active age group is 24-to-29 (20.8%; N = 75). The sophistication, associated with characters with a high purchasing power, also acts as a trigger for sexual activity, since 39.5% (N = 30) of the sophisticated female characters accentuate their sex appeal.

On the contrary, sexual activity is quite low in the 46-65 age group (13.3%; N = 48) and almost non-existent in the over-65 age group (1.4%; N = 5), as a result of the social identification of beauty with youth, as well as the limited role played in fiction by women over 45. The death or absence of the female characters’ partner, romantic failures, worn-out relationships and the influence of religion make up the rest of contextual factors that determine the absence of representations related to the sexuality of 49.2% (N = 349) of the sample of female characters, nevertheless the impact of these factors is much lower than that of the character’s age and narrative prominence.

Spanish television fiction promotes female monogamy, with 69.8% (N = 270) of the sexually active female characters only having sexual or romantic relationships with a single person, while 30.2% (N = 117) being involved with more than one partner. The end of a relationship is often linked to the start of a new one and most of the women change their partners very often. As in the case of sexual activity, the age of the characters also determines infidelity, which reaches its zenith among the 30-to-45 year-old female characters (42.7%; N = 50) and dramatically decreases among female characters over the age of 46 (8.5%; N = 10). The fact that the number of cases of infidelity suffered by women is larger among monogamous women (47.1%; N = 90) than among women who maintain relations with more than one person (37.2%; N = 71), reveals that infidelity is more frequent among male characters than among their female counterparts. Moreover, storylines related to male infidelity are more developed and better articulated than those related to female infidelity.

The stories included in the sample focus on the exploration of the first sexual experiences of the 18-to-23 year-old female characters (41.9% of the 31 women who have their first sexual experience, explicitly or implicitly depicted in the series), followed at a considerable distance by the groups of 24-to-29 year-olds (22.6%; N = 7) and 15-to-17 year-olds (19.4%; N = 6). Of the nine women who lose their virginity in an explicit manner, 44.4% (N = 4) belong to period dramas. With a few exceptions, the loss of virginity tends to be charged with a strong ritualistic atmosphere and is presented as a kind of liberating “psychodrama”, in the cultural sense given to this concept by Geertz (1973: 104) .

Spain’s domestic television fiction barely portrays the dark side of sexuality, since only 7.7% (N = 55) of the female characters face problems related to the sexual sphere. According to the different levels of sexual activity of the sample of female characters, the group of 30-to-45 year-old women faces more problems of this kind than the rest of the age groups (40.0%; N = 22 characters), followed by the 24-to-29 age group (20.0%; N = 11) and the 18-to-23 age group (16.4%; N = 9). The problems related to the sexual sphere revolve mainly around unwanted pregnancies (5.92%; N = 42) and the trauma resulting from some sort of abuse (2.67%; N = 19), which occasionally converge in the same female character. Only one young female character contracts one of these diseases (crabs) in a drama set in the 1970’s.

Of the unwanted pregnancies detected in the sample, 42 (5.9%) are mainly associated with the groups of 18-23 year-olds (33.3%; N = 14) and 30-45 year-olds (38.1%; N = 16). Only 0.4% (N = 3) of the women with unintended pregnancies decided to have an abortion, despite the increase in the number of voluntary abortions carried out in Spain between 2003 (8.8%) and 2012 (12.0%) (Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [MSSSI], 2012). 59.5% (N = 25) of unwanted pregnancies take place in stories set in the past, when women hardly had any effective contraceptive methods available. The fears and doubts raised by unwanted pregnancies respond to very diverse situations, such as the male partner’s reluctance to acknowledge paternity; the father being a married man or a casual lover; the precarious economic situation of the couple and, exceptionally, the pregnant woman’s professional career. However, the problems caused by unplanned pregnancy are eventually solved most of the times. When unplanned pregnancy is the result of rape or sexual abuse, the perpetrator is often previously acquainted by the victim, which is in line with a good portion of the actual sexual attacks that occur in Spain, where 27.0% of the attackers are acquaintances of the victim, 24.9% are relatives, and 20% are the victim’s own partner (Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social [MSPS], 2009).

Only three of the 360 female characters whose storyline is related to the sexual sphere exercise some kind of sexual violence, and this occurs in some of the many period TV series. These women are characterized negatively: Two of them sexually abuse younger men through different forms of coercion, while the third threatens a bullfighter with revealing his homosexuality if he does not support her political plans.

Discussion

The sexual construction of the analyzed female characters is determined mainly by physical appearance and age (Araüna, 2013;Glatzer, 2010;Glascock, 2001, 2003). The young female characters in the sample identify empowerment with sexual assertiveness, as well as with the acquisition of individual power and control (Gallager, 2014). The few women over 46 years of age related with sexuality either imitate the sexy style of young women with provocative clothing, or display sophistication that denotes the high social stratus which they usually belong to. The sexual activity of the less attractive female characters is also very limited and tends to revolve around the search for a sexual partner, one of the most reviled topics of popular cultural forms (Gill, 2007: 69).

Most of the representations of sexuality are incidental to the story (Eyal and Finnerty, 2007), particularly infidelities and unwanted pregnancies, and portray it as a kind of “truth” waiting to be discovered (Plummer, 1995: 132 ). Sexual intercourses are more common between unmarried couples (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012) and their representation tends to be very stereotypical (Eyal and Finnerty, 2009). The setting in the past of a sizeable part of the analyzed storylines does not substantially affect the sexual construction of women, even though period dramas are more likely to include subjects of social interest, for example the consequences of sexual violence and of not using methods to prevent pregnancies and the transmission of STDs.

Infidelity is one of the most recurrent scripts in the representation of sexual intercourse in the analyzed storylines, which is a similar result to that reached by Al-Sayed and Gunter (2012) in their research on British soap operas. Female infidelity appears to be linked with age, as most of these women are under 45 years of age, and it tends to be casual. These are two factors that tend to perpetuate the dominant myth of male sexuality as something “natural”, and reinforce the idea of the greater responsibility of women in this regard (Berridge, 2014: 340 ). Male infidelity frequently originates with complex triangulations, which turn the two women involved in the love triangle into rivals, confronted by a man. The female mistress is always younger than the unfaithful man’s wife or female partner.

Sexual promiscuity tends to be presented as an attribute of the character engaged in it, however occasional female infidelity is frequently justified by resorting to exogenous circumstances and is followed by repentance. Thus, even though most of the sexually active female characters are shown as sexually available, infidelity is still justified by the effects of alcohol or loneliness (Berridge, 2014: 336 ). In married female characters, infidelity is presented as a reaction to male infidelity. In general, the idea that women are more responsible about their sexuality than men (Berridge, 2014: 338) persists, which has been revalidated in other research studies carried out by Spanish scholars (Araüna, 2013; Galán, 2007).

Less than a quarter of the young women that star in stories related to sexual initiation lose their virginity in an explicit manner. “Abstinence” —posed as a desire to remain virgin until marriage— is the most common script in the sexual initiation stories set in the past and which culminates on the wedding night (Kelly, 2010). The dominant script in the stories set in the present time depicts virginity as a “stigma” that needs to be banished, and is usually redirected to the script about the “management” of how, when, where and who to lose this virginity with (Ibid.). Regardless of women’s age, the loss of virginity in Spanish television fiction constitutes a sort of “rite of passage”, a concept coined by the French anthropologist Van Gennep (1981) to mark the symbolic transition from a stage of life to another.

The analyzed stories tend to ignore the negative consequences of unprotected sex (Aubrey, 2004;Eyal and Finnerty, 2009;Van Damme, 2010). On the contrary, the consequences of “forbidden” sex are widely exploited in some dramas’ storylines, for instance relations with a priest or a nun; or with the boyfriend or husband of an acquainted woman (a workmate or a relative). These are relatively frequent topics in the stories set in the past, which occasionally add the age difference factor, at a time when a relationship between a woman and a younger man was frowned upon.

With the exception of only one female character who contracts an STD in a period drama, the only negative consequences of unprotected sex are unwanted pregnancies, a third of which occurs in the 18-to-23 age group. The unwanted pregnancy of one of the three teenagers who experience this situation, included in one of the few dramas targeting young audiences (El Barco, Antena 3), is downplayed by appealing to the apocalyptic context of the story (the end of humanity). The time in which the story is set does not condition the development of the storylines on unplanned pregnancies, with the exception of the married woman’s “obligation” to give birth and the stigma associated to single mothers in Spain in the past. In series set in the present, unwanted pregnancy is usually presented as an exclusively feminine problem (Berridge, 2014). Yet, despite the high number of abortions that are carried out in Spain every year (Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [MSSSI], 2012), only three of the 42 women with unintended pregnancy choose to abort, while another character fails to have one.

When unwanted pregnancy is the result of rape or abuse, the perpetrator is often part of the surroundings of the victim, which is consistent with a large part of the real attacks that occur in Spain (Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social [MSPS], 2009). On the contrary, despite the high levels of gender-based violence reported in recent years, domestically-produced television fiction presents this type of violence as a problem of the past, as it only includes two cases, set in the present, of women who are sexually abused. However, all storylines dealing with this topic aim to spread awareness to end with this social scourge.

The analysis has confirmed the overrepresentation of sex on television, as observed by other European and American authors (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012; Kunkel et al., 2005), however with some particularities that will be mentioned below. The dominant prototype that emerges from the representations is that of a young, attractive and sexy woman without major economic concerns (Gill, 2008). This is a type of character that fits the female models popularized by neoliberalism (Gallager, 2014; Gill, 2007; Gill and Scharff, 2011; McRobbie, 2009), even though their sexual relationships tend to be monogamous and infidelity is often narratively justified (Berridge, 2014). The association of female characters with sexuality is inversely proportional to their age and beauty, except in the case of girls and female teens, and directly proportional to the character’s narrative prominence, which is a trait widely highlighted by other researchers (Gill, 2007).

The context of these representations, particularly the characterization of female characters, plays an important role in the treatment given to the construction of sexuality (Aubrey and Gamble, 2014;Eyal and Kunkel, 2008;Farrar et al., 2003;Kunkel et al., 2007;Rivadeneyra, 2011), nevertheless the setting in the past of 34 of the 84 analyzed programs does not substantially change their sexual characterization. Moreover, the central role played by infidelity in most of side storylines suggest the inextricability of sex and love relationships, emphasized by Giddens (1992/1993: 1) in his seminal contribution to the subject.

By and large, it can be stated that the sample of representations offer a distorted image of sexuality (Al-Sayed and Gunter, 2012; Fisher et al., 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005; Signorielli, 2000), even though there are noticeable differences in this respect across genres and formats. The drama genre and the soap opera format pay closer attention to the didactic aspect of sexuality than the rest of the analyzed television fiction series (Al-Sayed & Gunter, 2012; Lacalle, 2013), especially the series set in the past and broadcast by the public channels La 1 and TV3. In general, Spanish television fiction tends to ignore the unintended consequences of sexual intercourse, sexually transmitted diseases and unplanned pregnancies (Aubrey, 2004; Aubrey and Gamble, 2014; Eyal and Finnerty, 2007; Kunkel et al., 2005). On the contrary, sex seems to be portrayed as the culmination of women’s empowerment.

The loss of virginity is one of the narrative themes of sexuality that is charged with the greatest degree of symbolism in Spanish television fiction representations. Although the storylines about this “rite of passage” (Van Gennep, 1981) adopt the different modalities of representation defined by Kelly (2010), most storylines opt for the “management” script, i.e., the couple’s management of their first sexual relation.

This research has focused on the more narrative aspects of the representation of female sexuality in Spanish television fiction, thus some important issues have been addressed superficially, as the frequent relation between love and sexuality. The identification of the variables focused on sexuality —which have been accurately discriminated from the rest of the descriptive and narrative codes (see Table 1) — has allowed us to carry out a precise and multifaceted analysis of the representation of female sexuality in television fiction, taking into consideration the content and the diverse underlying connections that exist within our object of study. However, the method used here is articulated and flexible enough to address the study of the sexual dimension of the representations, both of women and men, focused on areas such as family, workplace and even love. Beyond the accurate diagnosis of the construction of female sexuality in Spanish television fiction, which constitutes the specific subject of this research, the primary objective of our work is to reveal the prejudices that underlie these representations and to stimulate other scholars “to focus their energies on this challenging avenue of research” (Oliver et al., 2014: 93 ).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)