Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Convergencia

versión On-line ISSN 2448-5799versión impresa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.24 no.74 Toluca may./ago. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v0i74.4387

Scientific Article

Framing climate change in Chile: discourse analysis in digital media

1Universidad de Chile, Chile. jhasbun@med.uchile.cl

2Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia, Chile. paldunce@uchile.cl

3Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile.gblanco@uach.cl

4Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile. rodrigobrowne@uach.cl

This article presents a discourse analysis of four digital media press in Chile with regard to mitigation and adaptation to climate change. The research, unprecedented for the Chilean case, is aimed at acknowledging the news framings by means of which climate change is communicated, since the media are the main source of information on climate change for decision makers and citizens. The results show that the primary definers of the topic are the governmental actors of national level and the invisibilization of individuals and civil organizations in the process. Thus, we see a high degree of consensus between the visible actors with regard to the framing of economic opportunity and the absence of framings of critical ecology. The conclusions point that this imbalance might influence a design of public policies with a technocratic bias, losing the possibility of building an integral vision of the development of the country.

Key words: climate change; communication; framing; adaptation; mitigation

Este artículo presenta un análisis de discurso a cuatro medios de prensa digital en Chile respecto a la mitigación y la adaptación al cambio climático. La investigación, sin precedentes para el caso chileno, se orienta a conocer los encuadres noticiosos con que es comunicado el cambio climático, ya que los medios son la principal fuente de información del cambio climático para los tomadores de decisión y la ciudadanía. Los resultados muestran que los definidores primarios del tema son los actores gubernamentales de nivel nacional, y la invisibilización de las personas y organizaciones ciudadanas en el proceso. Vemos así un alto grado de consenso entre los actores visibilizados respecto al encuadre de oportunidad económica, y la ausencia de encuadres de ecología crítica. Las conclusiones apuntan a que este desbalance podría influir en un diseño de políticas públicas con un sesgo tecnocrático, perdiendo la posibilidad de construir una visión integral del desarrollo del país.

Palabras clave: cambio climático; comunicación; encuadres; adaptación; mitigación

Introduction1

Climate change, a challenge for public policies

The political will of democratic countries depends heavily on the list of priorities in the public agenda at any given moment; this is the reason why the power the media have in communication is fundamental, owing to their capacity to influence public opinion, a construct measureable by means of periodical opinion polls (Kingdon, 1995: 90 ).

We understand climate change not as a natural phenomenon, but one eminently political, as it comprises not only man-made transformations upon the various systems which support life, but besides in decision-making processes; this way, it requires high coordination levels of action and multiple changes in the understanding and designing of public policies (Giddens, 2010: 15 ).

This way, Brazilian Achim Steiner (2013) , executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme UNEP, has stated: “the challenge we face is neither technical nor normative; it is political: the current action pace is insufficient”, in regards to the possibility of limiting the increase in 2ºC of the planet’s temperature.

A way to approach the agenda setting process is the notion of framing, as it allows configuring the limits of a debate by establishing a definite number of alternatives, which will have be observable for decision makers at the moment of understanding, planning and managing a public policy problem (Pralle, 2009: 783 ).

Latin America and Chile facing climate change

Since climate change does not equally impact various latitudes and territories, it has differential effects inside each society, which for the Latin American case means that it hits harder those who are economically, politically, socially and culturally more vulnerable, reason why from this standpoint climate change policies may be considered developmental, as the mitigation of its impacts necessarily means to raise the population’s life conditions (Giddens, 2010: 20 ; Cannon and Müller-Mahn, 2010: 620 ).

This is relevant as there exists an imbalance between north and south hemispheres regarding the amount of: i) scientific output (IPCC, 2014: 842); and, ii) production of news on climate change (Schmidt et al., 2013: 1237 ) in favor of the first, which generates biases and distortions in the comprehension of the phenomenon by our societies, as research over the last three decades shows in a consistent manner that the general public and decision makers, as part of such audience, understand science and climate change fundamentally by means of the media2 (Boykoff and Yulsman, 2013: 360 ).

The noticeable economic growth in Latin America over the last decade has generated that a large number of our countries are considered middle income, which face critical disjunctives regarding climate change, as they have to address questions that are technically and politically difficult to answer: are we facing current or future vulnerability? Or else, are we focusing on the adaption to or the mitigation of climate change? There is evidence that indicates that middle-income countries are more vulnerable to climate change impacts (drought, food security, among others) than poor ones, in the dilemma of adaption v. development, since the transition from traditional ways of life to modern ones not only implies gains, but also losses (Fraser et al., 2013: 199 ).

The capacity to adapt to climate change in Latin America is low (IPCC, 2014: 1537), and even if our contribution to the emission of greenhouse effect gases is small, all the same we have to consider their mitigation. Moreover, the limited capacity of our States is recognized in: i) facing the combined tensions and processes involved in climate change; ii) the reduced number of national policies that consider variables of climate change; and, iii) the difficulties to solve the problems altogether, when decision makers are not trained or sufficiently informed, in contexts of budgetary fiscal restraint and conflicts at various governmental scales (Hardoy and Pandiella, 2009: 220 ).

In this context, Chile stands out by being the first country that applied the policies of the neoliberal recipe book, generating heavily marked (economic, political, geographical, environmental) inequality, reason why it is relevant to analyze news framings of climate change, as they will allow us to approach the process of agenda setting, political and public, in view of understanding what the horizon of possibilities that people can visualize at the time of thinking and acting before climate change is.

Media concentration in Latin America

A common feature in Latin America is the heavy concentration of media ownership, with important consequences for the plurality of information that sustain democratic States, as these have the function of observing and controlling the exercise of power in democracies (Sunkel and Geoffroy, 2001: 13 ).

The privatization over the 1990’s (with the exception of Uruguay), justified under the premise of introducing actors and generating more competitiveness, did not change the mono- or oligopolistic status of the info-communicational industries in Latin America, with the largest number of these industries in small countries such as Chile, Peru and Uruguay, with the radio as the least concentrated sector and telephone, as the most (Mastrini and Becerra, 2006: 117 ).

In this dynamic, the market has fixed the main strategies of the sector in Latin America “so that the State later adjusted the regulatory framework to such situation” (Mastrini and Becerra, 2006: 307 ). The Chilean case does not escape from such logic, but makes it deeper, because after the civil-military dictatorship the policy for the media was: “the best policy is to have none” (Sunkel and Geoffroy, 2001: 12 ), in which the non-State intervention became the disappearance of various media created by the end of the military government, a situation that made Human Rights Watch (1998: 49) point out that the freedom of expression and information in Chile was restricted “to a level possibly incomparable with that of any other democratic society in the occidental hemisphere”.

The concentration of media ownership has three consequences on the freedom of expression: i) the subordination of the media to economic powers; ii) the weakening if the journalists’ professional culture; iii) that the media are not channels for the citizens to express. For the case of Chile, such processes are accompanied by an “ideological monopoly”, and the cultural and political diversity was relegated to a marginal level by the entertainment industry (Sunkel and Geoffroy, 2001: 114-115 ).

In this panorama, when the debate focuses on highly complex topics —with important risks for human security such as climate change—, the effects of such processes are potentially catastrophic.

Media discourses on climate change

The central role of the media in the setting of the political and public agendas on climate change has elicited the analysis of the media discourse, especially in industrialized countries (Schmidt et al., 2013: 1239 ), with exceptions such as the case of India (Jogesh, 2012: 266 ), Brazil (Painter and Ashe, 2012: 2 ) and Peru (Takahashi and Meisner, 2013: 340 ). In the lengthy trajectory of the research on the media role covering environmental topics, it is not until the 1990’s when attention is paid to climate change (Anderson, 2009: 166 ), entering the agenda as a heavily politicized issue, especially in the United States and England (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004: 125 ), changing from a control of the discourse by climate scientists to the politicians with the “green speech” delivered by Margaret Thatcher to the Royal Society in 1988 (Anderson, 2009: 168).

Over the first half of the 1990’s the topic loses impulse when competing with topics such as the economic crisis and the Gulf War to emerge again in 1997 by virtue of the Kyoto Protocol, this time accompanied by new studies regarding the impacts of climate change on developed countries (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2007: 1190 ).

In the early years of the 20000’s in the U.S. and England attention was still paid by the media (Boykoff, 2007: 1198 ), especially in 2006, linked to Al Gore’s documentary “An inconvenient truth”.

Ironically, there has been poor coverage on climate change in developing countries, in comparative terms, even if they experience its worst effects (Painter and Ashe, 2012: 6 ).

From the interface between communication and politics, this article intends to understand how mitigation and adaption to climate change are communicated in Chile, by means of a discourse analysis on four digital press media over 2011-2013.

The question that guided this research is: how do the digital media present mitigation and adaption to climate change in Chile? In view of approaching the processes of public and environmental agenda setting by means of analyzing the news framings in the digital press.

Conceptual framework

The news framings of climate change in Chile were analyzed; these can be defined as “the core organizing idea for the news contents, which provides a context and implies what the central topic is by means of selection, emphasis, exclusion and production” (Ryan et al., 1991: 3 ). This way, the framings orient the perspective with which news are told, which produces narratives, which amplified in the public space by the media, contribute to the definition and constructions of visions of the world and lifestyles the individuals lead, with no disregard for the capacity of agency and interpretation they may have. News framings are important because of their ability to “define the terms of the debate without the audience realizing” (Tankard, 2001: 97 ). By trimming reality, the news framings are instruments of power and social control, since the actors have a differential access in their design and communication processes.

Hall et al. (1978: 647) notice the usual structures of news production, concluding that ultimately the media reproduce the definitions of the powerful, as credited sources. This way, they state that politics is the primary definer that configures and frames “what the problem is”. This initial framing provides the criteria with which all the subsequent contributions are deemed “relevant” or “irrelevant”.

This standpoint would define the political agenda that will define the media agenda, which will amplify these dimensions already framed for the audience, also defining at once, the priority topics (CervantesBaraba, 2001). Gandy (1989: 270) points out that “certain sorts of sources have been identified as more reliable than others. The official bureaucracies, or bureaucratically organized institutions, tend to be the most reliable, and as a result, the information provided by bureaucracies tends to dominate the media channels”.

From this perspective, it is relevant to consider, additionally, entrepreneurs and power interest groups, which also have capacity to set a media agenda. Hence, the media will be at a structured subordination before the primary definers (Hall et al., 1978: 650 ).

The theory of agenda setting allows grasping the link between public opinion, pressure groups, the media and decision makers by trying to answer the question why certain topics appear in the agendas, whereas others are neglected (Kingdon, 1995: 7 ).

Problems enter —become salient— and leave public and political agendas regardless of their objective state (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993: 142 ); while problems with no available or feasible solutions, even if they attract public attention and the government, are not likely to enter the decision agenda (Kingdon, 1995: 44 ).

Methodological framework

The qualitative content analysis allows computing and systematizing the information3 in order to generate objective inferences of the emergence and use of certain analysis objects on such processing.

The problem that guides this research is close to the field of studies called “science and politics”, a complex interface in which the concepts of knowledge and power concur. From such viewpoint, the most pertinent analysis device is Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which is utilized in this research.

Van Dijk (2002: 4) orients the perspective of CDA before the discourse, as it stresses the prevailing social problems, choosing “the standpoint of those who suffer the most, and critically analyzing those in power, those responsible and those who own the means and the opportunity to solve such problems”.

We now see that in the texts a number of discursive references concur; these are negotiated and governed by the differential of power each possesses, which on occasion makes them places for struggle and control, showing traces of conflicting ideologies, for power rests upon relations of difference and particularly on the effects of differences in social structures.

In this paper we analyze the news framings used to represent climate change, which become narratives that possess incipient or advanced degrees of institutionalization. When these narratives express conflicting positions, product of the clash between those who aspire to change the social structures and those with interests in maintaining them, become discourses, as control devices for the differential access to decide regarding the use of certain resources (economic, political).

Analysis units

The analysis unit is the news item, which in the media is a formal report of events considered significant for the target audience, commonly publishes shortly after the information becomes available (Chandler and Munday, 2011: 227 ). A referential and objective informational communication is expected, with no biases, even if the information selection is determined by news values, i.e., by the informal journalistic criteria adopted by the selections, prioritization and presentation of the events by the editorial line of the medium.

Sample

The sample we considered is the digital press. In Chile, the digital press has a credibility similar to that of the printed; it is perceived as the most independent to report and with similar quality. It is the fourth communication means utilized in the country, after open TV, radio and cable TV, slightly surpassing printed newspapers (UDP-Feedback, 2011: no page). Its temporary outreach includes the Segunda Comunicación Nacional de Cambio Climático [Second National Communication on Climate Change] (August 30th, 2011) and the creation of Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia [Center of Weather and Resilience Science] (October 31st 2013), since it is a relevant period in terms of the relevance the topic was obtaining in the national agenda.

In order to find out the diversity of tendencies present in the political discourse, four national digital press media have been selected (La Nación, El Mostrador, La Tercera, El Mercurio) both because of their editorial-political profile (center-left / right) and readership (table 1 4). The duopoly that exists in the media (digital and printed) expresses in the concentration levels of readership the conservative media have over the liberal (Sunkel and Geoffroy, 2001: 17 ).

From the corpus of news items, the information will be codified in two central nodes: “climate change mitigation” (CCM) and “climate change adaption” (CCA), from which a second-order codification will be made on different framings (sub-nodes) in view of facilitating discourse analysis.

Selection criteria

The criteria for sample selection are as follows:

Include national news items, including those from Chileans abroad speaking of the country or else, foreigners in Chile speaking of the country. Editorials, opinions and interviews were omitted, since their logic does not respond to the style structure of the news items.

News items that in their heading, subheading, first and second paragraph mention any of the following concepts: i) climate change; ii) global warming, iii) global change; and, iv) greenhouse effect.

Results

By applying the selection criteria defined in the methodological framework, we obtained a corpus of 58 news items on climate change in Chile over the analyzed period, on which discourse analysis will be made. If we take the set of the four analyzed media, we find that a national news item on climate change is published every 12.78 days. The electronic medium El Mostrador does not present national news items on climate change, as it has international agencies as information sources.

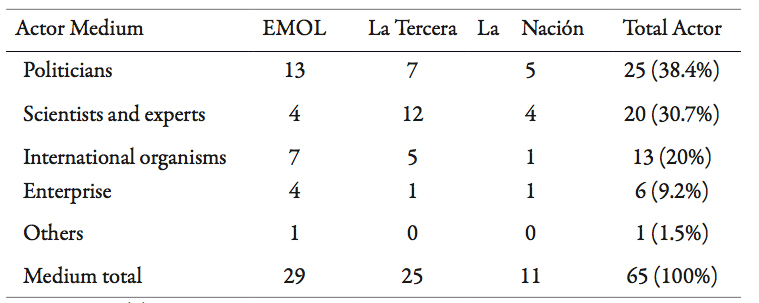

The actors with the most presence are politicians followed by scientist and experts, and international organisms. Entrepreneurs are rather behind, while the absence of citizens is noticeable (table 2).

As regards each analyzed node and sub-node, the same number of items is noticed for mitigation (N=28) and adaption (N=29) to climate change in Chile.

For the analysis, we have defined CM as: “human intervention to reduce sources or improve greenhouse gas sinks”. From the standpoint of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), since it is caused by human action, fundamentally by the burning of fossil fuels that release greenhouse gases such as CO2, it is possible to perform various mitigating activities that contribute to decrease the volume of such gas in the atmosphere.

CCM has been subdivided for the analysis of four framings: i) “reduction of emission intensity”; ii) “absolute emission reduction”; iii) “goals of carbon neutrality”; and, iv) “other mitigating actions”.

Almost a half of the studied news items (28/58)5contains information referring to CCM, either explicitly or implicitly. Most of the news items orients to framing of “other mitigating actions” (12), followed by “reduction of emission intensity” (10), “goals of carbon neutrality” (5) and “absolute reduction of emissions”, which does not have any reference.

Of the four framings analyzed, three present news items in three of the reviewed digital media with climate change items for Chile, being the media with the largest number of items La Tercera and El Mercurio (both with 9), followed behind by La Nación, with two items.

Furthermore, CCA has been defined as: “adjustments in human or natural systems as a response to prospective or actual climate stimuli, or their effects, which may moderate the damage or else take advantage of their beneficial aspects”, this node has been subdivided into four framings: i) “planning”; ii) “vulnerability”; iii) “economic risk”; and, iv) “existing measures”, taking as references the framings found by Juhola et al. (2011: 456).

In a half of the analyzed items (29/58) information referring to CCA is noticed implicitly or explicitly. Most of the items orients to “planning” (20), followed by “vulnerability” and “economic risk” (both 15), being the last “existing measures” (8). Out of the four framings analyzed for CCA, three present items in three of the revised digital media that contain news on climate change in Chile, and only “vulnerability” has no references in El Mercurio, even if it is the medium with the largest number of news items on climate change in Chile.

Discussion

Mitigation or adaption to climate change

Being Chile a developing South American country, with a mean income and an OECD member, it is found in an interregnum: it is not a wealthy and developed country, neither is it one in poverty situation, which makes complex the decision process in the adaption/mitigation disjunctive. By and large, it is advised that developed countries invest on mitigation mainly, whilst developing ones must do so on adaption; basically owing to the intensive use of fossil fuels by the former and because the latter must invest less to bridge the gaps with developed countries and deliver better life conditions to their inhabitants, in what Giddens (2010: 17) calls “development imperative”.

In this dynamic, developing countries resort to adaptive reactions, since they do not have the resources to face the prospective impacts, while international cooperation and technology transfer play a fundamental role in supporting the change to a planned adaption.

Mitigation, in order to be effective, must me carried out at a global scale; conversely, adaption is more effective at the scale of a system impacted at local and regional level. Mitigation has an established measurement; on the contrary, being aware of the benefits of adaption depends on social, economic and political contexts (Broomell et al., 2015: 72 ). The benefits of mitigation will be noticed in decades to come, owing to the prevalence of GG in the atmosphere; while those of adaption are more effective in the present, for they reduce vulnerability to climate variability. And to the extent that climate change continues, the benefits of adaption will increase over time. The question that captures the problem points at: which combinations of emission reductions and adaption can better ameliorate the impacts of climate change?

After studying the interrelations between adaption and mitigation, IPCC puts forward disjunctives and synergies between both measures, since one has consequences on the other, reason why they must be designed to make the most of complementariness, reducing their negative interferences (IPCC, 2014), Ayers and Huq (2008: 757) pinpoint the benefits of integrating both approaches at project level in Bangladesh, claiming that it goes beyond the alignment of interests, fostering the support to adaption among the defenders of the “strong” mitigation agenda, who had been cautions about adaption in the past.

Somorin et al. (2012: 292) , in their discourse analysis of response policies addressing climate change in Congo River forests, found three discourses: only-mitigation policies; policies unrelated to adaption and mitigation; and, integrated policies of mitigation and adaption.

In this last discourse, the framings we found point at: i) there are new opportunity windows for synergies; ii) it is possible to design a measurement to integrate one to the other; iii) apparently they possess similar institutional and juridical frameworks for their design and implementation; and, iv) the fact that they share a policy of results to reduce poverty, conserve biodiversity and promote development. It is worth underscoring that the conflicting coalitions after the three previously mentioned discourses underscore their positions and interests with financial, power, control, knowledge, influence and justice.

This research results demonstrate that the reviewed digital press exposes mitigation and adaption without deepening into the benefits and costs of applying one strategy of the other. This unclear definition of both terms may be associated to the fact that in general few news items on science include information on the scientific process (Alley, 2012: 174 ; Arcila-Calderón et al., 2015: 86 ), and the Chilean case is not the exception, as they do not explain the grounds on which mitigation and adoption actions become meaningful (Jang and Hart, 2015: 16 ).

It is important to notice that the structure of the “news” format does not reach more than 500 words on average (Sterman, 2011: 817 ), because of that there is difficulty to communicate the contexts of meaning of the events featured, as the delivery of the largest amount of information in the smallest possible space is privileged, which plays against complex topics. This adds to the low reading comprehension of Chilean adults,6 the very low schooling level7 and the poor consumption of literature in general,8 this situation is also distinguished by Sterman (2011: 816) for the case of American audiences. This produces a breach between the understanding of basic sciences and the Summaries for those responsible for the policies,9 which at least require 17 years of study to be understood.

Mitigation

In the analyzed sample, mitigation appears mainly at transnational level, in international meetings and conferences (for instance, the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP17) and at national level, both as a central government response (developing mitigation models) and in the endeavors made by entrepreneurial actors (corporate mitigation); this concurs with Olausson’s (2009: 430) findings after analyzing three Swedish newspapers.

Mitigating actions are usually unfolded at macro-level (national or transnational); there are no news items that connect mitigation with individual actions or voice the concern of nongovernmental organizations involved.

Ockwell et al. (2009: 320) state that communication plays an essential role regarding effective mitigation, pointing out that it has two roles: the first, to facilitate the public acceptance of regulations (top-down), and the second, to stimulate grassroots actions by means of an effective and rational commitment to climate change (bottom-up). They point out that only the combination of both approaches will allow increasing the involvement level of people with climate change, contributing to surpass the barriers perceived at structural-social level and at subjective-individual level.

The way in which mitigation is framed by the studied digital press media orients to narratives that stress the political dimension, relegating to a lower level the scientific dimension, which allows proposing that in the communication of mitigation, in these Chilean press media, it is politics the one that defines the limits of mitigation, both explicitly (“what is said”) and implicitly (“what is not said”). The world of the large corporations seems to be associated to measures of carbon neutrality, while SMEs appear neither as sources nor are mentioned by the visible actors. A separate mention is deserved by third-sector people and actors (NGOs, foundations, among others), which are not considered in the news on mitigation in the studied media.

In Chile there is a balance between news items on adaption and mitigation of climate change over the period comprehended in the analysis, which contrasts with what occurred in Peru, where between 2000 and 2010, one notices that the adaption strategy (65%) amply surpassed that of mitigation (17%) (Takahashi and Meisner, 2013: 436 ).

Adaption

Vicuña (2012) points out that, in a simple manner, it is possible to perceive adaption as a (current) contextual reduction or as a (future) result of vulnerability. In this disjunctive, wealthy countries should concern about solving future vulnerability, while the poor, about the current, a situation which in middle-income countries such as Chile becomes complex, as they should take care of both, for which they should look for confluence. Chile started their way to adaption heavily stressing knowledge development to deal with the present vulnerability, however at present it would be moving toward the resolution of current vulnerability problems.

Bassett and Fogelman (2013: 42) present a content analysis that shows the prevalence (70%) of the “adjustment adaption” approach over “transformative adaption” (3%). In the case of the analyzed items, this prevalence is also noticed, where climate impacts are considered the main source of vulnerability, disregarding the social roots (“transformative adaption”) in such manner that the media discourse does not express the need to produce structural transformations in the political, social and individual life, and rather express the standpoint of incremental reforms, which in spite of leading in the long term to changes in the individuals’ behaviors, we do not know if are enough to prevent the degradation of the environment to the point of allowing sustainability for future generations.

In the analyzed sample, adaption mainly arises as planning, this is to say, as a search for solutions for the impacts of climate change. In the case of England, this narrative focuses on the planning processes with an emphasis on the revision of the existing planning policies (Juhola et al., 2011: 456 ).

The case of Chile shows an expectable lower maturation level in the planning discussion. Since at present the first steps are being taken to generate adaption policies, with an emphasis both on the production of scientific information and on national and international meetings for discussion.

Second in relevance, the framing of vulnerability, in which adaption is seen as a response to the perceived vulnerability of climate change impacts (Juhola et al., 2011: 456 ). In the case of Sweden, this framing is connected to extreme climate events such as floods. In Chile, vulnerability is observed as the projection of future impacts, this is to say, climate change is not considered to be occurring at present.10 Once again, there is no deepening into the social and historical aspects of vulnerability, which influences the way we will conceive adaption, for “the adaption policy will be framed according to how risk and vulnerability are conceptualized” (Bassett and Fogelman, 2013: 52 ).

Both elements (disconnection from vulnerability and from the current exposition to climate change, and the disconnection from vulnerability’s social aspects) generate: i) the audiences’ lack of comprehension regarding the most vulnerable and exposed populations to the effects of climate change; and, ii) lack of understanding of the need to act decreasing the current economic and social vulnerability, being those populations the most vulnerable to the present and future impacts of climate change.

Thirdly, the narrative of “economic risk”, in which adoption is presented as current and future economic costs and risks (Juhola et al., 2011: 456 ), with broad support on politics (8 actors) and emerging not only as costs but also as business opportunities. This positive vision of economic opportunity points at the framing of ecologic modernization, in recent decades sustained in England by the New Labor government (Uusi-Rauva and Tienari, 2010: 496 ), which contrasts with the emerging position of the media associated to the Chilean left-center (lanacion.cl=1), which tend to underline negative effects such as losses in employment and infrastructure.

For Cannon and Müller-Mahn (2010: 622) , it is fundamental to separate the concept of “development” from that of “economic growth”, which have been mistaken as of the 1980’s and which in the sample tend to concur on the narrative of “economic opportunity”. This narrative harbors the idea that economic growth and wealth accumulation by the rich will eventually permeate down to the lower layers of society,11 an idea defended by the right-wing think tanks12 in Chile, advocates of the economic model taken by the military government in the eighties, and which has not been effectively challenged by the democratic governments in recent decades.

This way, economic growth is not climate change adaption itself, but a concept of “meaningful development”, focused on directly improving the people’s lives, but not as a secondary effect of what other actors (corporations or governments) do in their search for profit and growth (Cannon and Müller-Mahn, 2010: 624-625 ). Hence, one can talk of an “economic bias” of the decision makers, who exclusively define the problems as an issue of calculating costs and benefits (Dewulf, 2013: 327 ).

These biases correspond with the Chilean elites’ responsibility dodging in this regard claiming in their discourses: a) the limited information provided by official agencies and the media; b) lack of scientists’ clarity; c) insufficient measures at institutional level; d) structural and institutional causes and conditions; e) State responsibility and regulatory failures (not business failures) (Parker et al., 2013: 1359 ).

Owing to this, while the international community (“top-top-down”) and social pressure (bottom-up) remain inactive, it is not expectable that the elite takes steps and make the necessary changes to stop climate change, for “the actors can behave strategically framing the scale of the problem, placing themselves in the center of power or dodging the responsibility moving it upwards or downwards” (Dewulf, 2013: 327 ).

Finally, the “existing measures” framing, which in opposition to that of planning deals with the current climate change, not the projected (Juhola et al., 2011: 456 ), emerges enumerating actions oriented to contain impacts on agriculture (4 out of 7 items) with a particular focus on the management of hydric resources. Even if the number of items is low in relation with the sample (4/58), the tendency pinpoints that in Chile policies are aligning toward the agribusiness, especially winemaking.

Policy as primary source

The actors made visible by the sample that tend to group as primary sources are fundamentally politicians (N=23), accounting for 67.6%; far behind are the entrepreneurs (N=7) with 20.5% and finally the scientists (N=4) with only 11.8%. There are no citizen actors in these narratives. These meager figures of scientists reporting on climate change are consistent with what occurs in the U.S., where “their voices are frequently marginalized in the arena of the public policies” (Alley, 2012: 178 ).

The practice of excluding society (people and organizations) as sources of information, i.e., with an active role in the construction of debate in the public space documented by the analyzed media, fractures “the dialogical relation that would have to take place among the actors of the political communication” ( Reyes Montes, 2007: 129 ).

In a study on the role of the press in the construction of environmental representations in inhabitants of Saltillo, Mexico, Carabaza (2007: 64) puts forward that “civil organizations, citizens and specialists are marginalized from the information, as they are sporadically considered important information sources, maybe owing to these groups’ lack of communication strategies or the professional routines imposed to journalists for information collection”.

This way, politics defines and frames the problem and its solutions (adaption and mitigation), which implies that decision makers not only “make decisions”, but almost in solitary they discuss the final ruling. Ordinary scientists and citizens do not have the power themselves to influence the agenda setting, which the studied media deliver to politics, this way, there is need for a counterweight that levels the power to decide on actors other than politicians and entrepreneurs.

A problem that arises from such prevailing proposition is the fact that political signals in news items on climate change “activates ideological beliefs and makes such beliefs predictors of greater concern” than those forecast by the scientific elites, with or without a consensus (Alley, 2012: 178 ; Wiest et al., 2015: 194 ). This is relevant, because in the studied sample for the Chilean case most of the political actors presented are governmental agents or supporters of President Sebastián Piñera.13

In the analyzed media, the risk that appears is that since visible actors possess a homogenous political lean (right) will ideologically taint the audience reception, a situation that musty be solved, such as Giddens (2010) points out the need to avoid turning climate change into political capital, as it will make political work difficult in the long run and will also divide the public opinion with an ideological-political cleavage.

The process of “problem definition” is relevant because it builds the social significance of the issue dealt with, its meaning, implications and urgency (Rochefort and Cobb, 1994: 28 ). The fact that the definition of a complex problem is eminently carried out by politics is not a problem in itself, because if there exists good understanding of the scientific process, the broad scientific consensus expressed in the IPCC report as well as the necessary mitigating and adaption actions may be obtained.

Sterman and Booth-Sweeney (2007: 235) verified that adults with substantive training in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) experience systematic biases in their judgments, decisions and assessments of the dynamics of the climate system, when they performed an exercise with MIT14 students taking the Summary for Policy Makers from the third IPCC assessment report as a reference.

From this standpoint it is not feasible to assume that political actors are capable of understanding and communicating a complex process such as climate change to the audiences, since in the United States, these people are demographically similar to the entrepreneurial and governmental leaders, a situation that does not necessarily agree with the educational profile of Chilean political actors.

Invisibility of people and social organizations

Separating people and local communities from the news framings generates: i) poor comprehension —acquisition and use of correct factual knowledge; ii) erroneous perceptions —looks and interpretations based on beliefs and prejudices; and, iii) poor commitment —personal connection that includes cognitive, affective and behavioral dimensions— by the public (Wolf and Moser, 2011: 548; Ford and King, 2015: 144 ). This is so because “the audience’s interpretation […] are clearly constrained by what is informed, by what is omitted and, maybe more fundamentally, by the news implications that set limits to the citizens’ aptitude to influence politics” (Edelman, 2002: 113 ).

When the news items systematically make people and communities invisible as regards their role before climate change, what is latently being spelt is disaster. Let us remember that these are socially built events, “product of the impact of a natural disaster on people whose vulnerability has been created by social, economic and political conditions” (Cannon and Müller-Mahn, 2010: 622 ).

This information asymmetry among the key actors can confuse the audiences, putting people at unnecessary risks (Aldunce et al., 2014b), situation that can be observed as “native externalities”, a product of narratives that exacerbate the role of decision makers and experts by using “top-bottom” and “command and control” approaches. As a result of these mechanistic proposals, “in this narrative a fundamental role is given to governmental agencies and the professionals, which tends to limit the role of communities (Aldunce et al., 2014a: 259).

Conclusion

Chile, as a middle income country, lives tensions between its political-economic elites, which base their programs on economic growth with strong negative externalities for the environment, and citizen sectors that show disposition to look for alternative development options, albeit maybe expecting their leaders bring up such options in the debate.

This work offers unpublished empirical evidence regarding the media framings to communicate climate change in Chile used by four digital press media with high readership levels and recognition by various actors of the country: La Nación, El Mostrador, La Tercera and El Mercurio.

The first general finding is that these tensions on development models are not presented in the four media studied for the case of climate change, which therefore favors the elites’ discursive stance.

The way climate change is represented in the media is key to inform people and communities about their responsibilities and rights regarding a suitable provision of Global climate Stability,15 and in the case that such supply is scarce, which are the daily actions that have to be performed to contribute with them or regarding preparation for action in case the plans designed to minimize the associated risks fail.

Thus, we notice that vulnerability can also be created by deficient conditions of knowledge circulation, cultural capital that would enable preparation and precaution; but in a way as crucial or more than the former, having access to perceptions, values and regulations which, all in all, support the visions of the world and lifestyles of people and their communities coherent with a transformation into a low-carbon civilization.

The analyzed media, representatives of political tendencies with access to power in Chile at present, are consistent in moving the actions of mitigation and adaption to climate change away from people and the locale level, minimizing the potential of the media to change the behavior of the individuals, their practices and social structures

REFERENCES

Aldunce, Paulina et al. (2014a), “Framing disaster resilience. The implications of the diverse conceptualisations of ‘bouncing back’”, en Disaster Prevention and Management, año 23, núm. 3, Reino Unido: Emerald. [ Links ]

Aldunce, Paulina et al. (2014b), “Resilience for disaster risk management in a changing climate: Practitioners’ frames and practices”, en Global Environmental Change, núm. 11, Reino Unido: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Alley, Kristen (2012), “Mass media roles in climate change mitigation”, en Chen, Wei-Yin, Steiner, John, Suzuki, Toshio y Lackner, Maximilian [eds. ], Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Anderson, Alison (2009), “Media, Politics and Climate Change: Towards a New Research Agenda”, en Sociology Compass, núm 3, Estados Unidos: Wiley. [ Links ]

Arcila-Calderón, Carlos et al. (2015), “Media coverage of climate change in spanish-speaking online media”, en Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, año 22, núm. 68, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Ayers, Jessica y Huq, Saleemul (2008), “The value of linking mitigation and adaptation: a case study of Bangladesh”, en Environmental Management, año 43, núm. 5, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Bassett, Thomas y Fogelman, Charles (2013), “Deja vu or something new? The adaptation concept in the climate change literature”, en Geoforum, núm. 48, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Baumgartner, Frank y Jones, Brian (1993), Agendas and instability in American politics, Estados Unidos: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Boykoff, Maxwell y Boykoff, Jules (2004), “Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press”, en Global Environmental Change, año 14, núm. 2, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Boykoff, Maxwell (2007), “Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006”, en Area, año 39, núm. 4, Maiden (MA), Estados Unidos. [ Links ]

Boykoff, Maxwell y Boykoff, Jules (2007), “Climate change and journalistic norms: A case study of US mass-media coverage”, en Geoforum, núm. 38, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Boykoff, Maxwell y Yulsman, Tom (2013), “Political economy, media, and climate change: sinews of modern life”, en Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, año 4, núm. 5, Estados Unidos: Wiley . [ Links ]

Broomell, Stephen et al. (2015), “Personal experience with climate change predicts intentions to act”, enGlobal Environmental Change , núm. 32, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Cannon, Terry y Müller-Mahn, Detlef (2010), “Vulnerability, resilience and development discourses in context of climate change”, en Natural Hazards, vol. 55, núm. 3, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Carabaza, Julieta (2007), “El papel de la prensa en la construcción de las representaciones sobre la problemática ambiental en los habitantes de Saltillo, Coahuila”, en Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, año 8, núm 24, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Cervantes-Baraba, Cecilia (2001), “La Sociología de las Noticias y el Enfoque Agenda-Setting”, en Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, año 14, núm 43, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Chandler, Daniel y Munday, Rod (2011), Dictionary of media and communication, Reino Unido: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes (2012). Encuesta Nacional de Participación y Consumo Cultural. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.cultura.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/ENPCC_2012.pdf [10 de marzo de 2017 ]. [ Links ]

Dewulf, Art (2013), “Contrasting frames in policy debates on climate change adaptation”, en Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, año 4, núm. 4, Reino Unido: Wiley. [ Links ]

Edelman, Murray (2002), La construcción del espectáculo político, Argentina: Manantial. [ Links ]

Ford, James y King, Diana (2015), “Coverage and framing of climate change adaptation in the media: A review of influential North American newspapers during 1993-2013”, en Environmental Science & Policy, año 48, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Fraser, Evan et al. (2013), “Vulnerability hotspots: Integrating socio-economic and hydrological models to identify where cereal production may decline in the future due to climate change induced drought”, en Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, año 170, núm. 15, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Gandy, Oscar (1989), “The surveillance society: information technology and bureaucratic social control”, en Journal of Communication, año 39, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Wiley . [ Links ]

Garreaud, René (2011), “Cambio Climático: Bases físicas e impactos en Chile”, en Revista Tierra Adentro (INIA-Chile), núm. 93. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://dgf.uchile.cl/rene/PUBS/inia_RGS_final.pdf [20 de junio de 2015 ]. [ Links ]

Giddens, Anthony (2010), La política del cambio climático, España: Alianza. [ Links ]

Hall, Stuart et al. (1978), “The social production of news”, en Marris, Paul y Thornham, Susan (2000), Media Studies. A reader, Estados Unidos: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Hardoy, Jorgelina y Pandiella, Gustavo (2009), “Urban poverty and vulnerability to climate change in Latin America”, en Environment and Urbanization, año 21, Estados Unidos: Sage. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch (1998), Los límites de la tolerancia. Libertad de expresión y debate público en Chile, Chile: LOM Ediciones. [ Links ]

IPCC (Intergobernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2014), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: IPCC Working Group II Contribution to AR5. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://ipcc-wg2.gov/AR5/ [20 de junio de 2015 ]. [ Links ]

Jang, Mo y Hart, Sol (2015), “Polarized frames on ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ across countries and states: Evidence from Twitter big data”, enGlobal Environmental Change , núm. 32, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Jogesh, Anu (2012), “A change in climate?: Trends in climate change reportage in the Indian print media”, en Dubash, Navroz [ed. ], Handbook of Climate Change and India, Inglaterra: Earthscan. [ Links ]

Juhola, Sirkku et al. (2011), “Understanding the framings of climate change adaptation across multiple scales of governance in Europe”, en Environmental Politics, año 20, núm. 4, Reino Unido: Routdledge. [ Links ]

Kingdon, John (1995), Agendas, alternatives and public policies, Estados Unidos: Little, Brown. [ Links ]

Mastrini, Guillermo y Becerra, Martín (2006), Periodistas y magnates: estructura y concentración de las industrias culturales en América Latina, Argentina: Instituto Prensa y Sociedad, Prometeo Libros. [ Links ]

Melo, Fabiola (2013) "Mineduc: más de 5 millones de chilenos mayores de 18 años aún no termina la educación escolar", en La Tercera. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.latercera.com/noticia/mineduc-mas-de-5-millones-de-chilenos-mayores-de-18-anos-aun-no-termina-la-educacion-escolar/ [10 de marzo de 2017 ]. [ Links ]

Ockwell, Donald et al. (2009), “Reorienting Climate Change Communication for Effective Mitigation”, en Science Communication, año 30, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Olausson, Ulrika (2009), “Global warming--global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty”, en Public Understanding of Science, año 18, núm. 4, Reino Unido: Sage. [ Links ]

Painter, James y Ashe, Teresa (2012), “Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007-10”, en Environmental Research Letters, año 7, Reino Unido: IOP Publishing. [ Links ]

Parker, Cristián et al. (2013), “Elites, climate change and agency in a developing society: the Chilean case”, en Environment, Development and Sustainability, año 15, núm. 5, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Pralle, Sarah (2009), “Agenda-setting and climate change”, enEnvironmental Politics , vol. 18, núm. 5, Reino Unidos: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Reyes Montes, María Cristina (2007), “Comunicación política y medios en México: el caso de la reforma a la Ley Federal de Radio y Televisión”, en Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, vol. 14, núm. 43, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Rochefort, David y Cobb, Roger (1994), The politics of problem definition, Estados Unidos: University Press of Kansas. [ Links ]

Ryan, Michael et al. (1991), “Risk Information for Public Consumption: Print Media Coverage of Two Risky Situations”, Health Education and Behavior, vol. 18, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Schmidt, Andreas et al. (2013), “Media attention for climate change around the world: a comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries”, enGlobal Environmental Change , 23, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Somorin, Olufunso et al. (2012), “Congo basin forests in a changing climate: policy discourses on adaptation and mitigation (REDD+)”, enGlobal Environmental Change , vol. 22, núm. 1, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Steiner, Achim (2013), Director del Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente (PNUMA), La Segunda online, 5 de noviembre de 2013. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.lasegunda.com/Noticias/CienciaTecnologia/2013/11/890458/Advierten- que-controlar-aumento-de-la-temperatura-de-la-tierra-se-hace-mas-dificil [20 de junio de 2015 ]. [ Links ]

Sterman, John y Booth-Sweeney, Linda (2007), “Understanding public complacency about climate change: adults’ mental models of climate change violate conservation of matter”, en Climatic Change, año 80, núm. 3-4, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Sterman, John (2011), “Communicating climate change risks in a skeptical world”, enClimatic Change , año 108, núm. 4, Alemania: Springer. [ Links ]

Sunkel, Guillermo y Geoffroy, Esteban (2001), Concentración económica de los medios de comunicación, Chile: LOM Ediciones. [ Links ]

Takahashi, Bruno y Meisner, Mark (2013), “Agenda Setting and Issue Definition at the Micro Level: Giving Climate Change a Voice in the Peruvian Congress”, en Latin American Policy, año 4, núm. 2, Estados Unidos: Wiley . [ Links ]

Tankard, James (2001), “The empirical approach to the study of media framing”, en Reese, Stephen y Gandy, Oscar [eds. ], Framing public life: Perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world, Estados Unidos: Routledge. [ Links ]

UDP-Feedback (2011), Primer estudio nacional sobre lectoría de medios escritos, Chile: Escuela de Periodismo Universidad Diego Portales. [ Links ]

Uusi-Rauva, Christa y Tienari, Janne (2010), “On the relative nature of adequate measures: Media representations of the EU energy and climate package”, enGlobal Environmental Change , año 20, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Van Dijk, Teun (2002), “Critical discourse studies: a sociocognitive approach”, en Wodak, R. y Meyer, M. [eds. ], Methods of critical discourse analysis, Inglaterra: Sage. [ Links ]

Vicuña, Sebastián (2012), “Adaptation challenges for middle income countries: the experience of Chile”, en Centro de Cambio Global UC. Adaptation Futures. International Conference on Climate Adaptation (PPT), Estados Unidos. [ Links ]

Wiest, Sara et al. (2015), “Framing, partisan predispositions, and public opinion on climate change”, enGlobal Environmental Change , núm. 31, Reino Unido: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Wolf, Johanna y Moser, Susanne (2011), “Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: insights from in depth studies across the world”, en WIRES Climate Change, año 2, Estados Unidos: Wiley . [ Links ]

1Research funded in the context of project FONDAP #1511009, “Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia” [Center of Climate Science and Resilience]: University of Chile, Austral University of Chile, and University of Concepcion, Chile.

2Such as television, newspapers, magazines, radio, online news, aggregators, blogs and social media.

4Tables are at the Annex, at the end of the present article (editor’s note).

5This figure (28 news items) does not consider the juxtaposition phenomenon, by means of which a particular item can refer to a different framings. Henceforth, figures presented respond to the same phenomenon.

6Centro de Microdatos de la Universidad de Chile [Center of Microdata of the University of Chile] (2013) points out that functional illiteracy reaches 44% of the country’s adult population, which are similar to the figures for 1998.

75.2 million people over 18 years of age have not finished secondary education in Chile (42,9%) (Melo, 2013).

831.3% of the population buys a book a year on average. Encuesta Nacional de Participación y Consumo Cultural. Análisis Descriptivo [National Survey of Cultural Participation and Consumption] (Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes, 2012).

10For example, by means of sustained and severe droughts experienced in the country, with a rain regime decreasing for decades now in the center and the south. Garreaud (2011) lists the impacts observed in Chile over the XX century those projected for XXI.

12The most important: “Libertad y Desarrollo”, “Centro de Estudios Públicos”, “Fundación Jaime Guzmán”. The neoliberal discourse states that the best way to reduce poverty is by means of economic growth.

13Center-right president (Partido Renovación Nacional), he was the president of the country from 2010 to 2014.

15La Estabilidad Climática Global es el bien público global amenazado por el cambio climático. Office of Development Studies (ODS) (2002), Profiling the Provision Status of Global Public Goods. An ODS Staff Papear. United Nations Development Programme, New York

Received: October 03, 2015; Accepted: September 12, 2016

texto en

texto en