Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Convergencia

versão On-line ISSN 2448-5799versão impressa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.23 no.72 Toluca Set./Dez. 2016

Scientific Articles

Socio-educational care and severe mental disorder: housing as a basis for intervention

1Universidad de Oviedo, España. garciaomar@uniovi.es

2Universidad de Oviedo, España. vipe@uniovi.es

3Universidad de Oviedo, España. storio@uniovi.es

The paradigm shift in mental health opens the door to a multidisciplinary approach. We advocate the need to invest in the recovery of people with Severe Mental Disorder from a socio-educational perspective, beyond the classic medical-clinical approach. The literature is reviewed and the results of various programs to support housing as a centerpiece of community intervention are analyzed. Improved personal and social functioning, fewer revenues, greater satisfaction and quality of life at lower cost is evidence. It is therefore crucial setting public policy of social action that promotes the conditions necessary to achieve social justice and inclusive citizenship. The relevance of Social Pedagogy and Social Education in achieving this goal and in improving their quality of life is concluded. We demand their theoretical and practical space in the field of mental health.

Key words: mental illness; housing; social inclusion; socio-educational intervention; social justice

El cambio de modelo de atención en salud mental abre las puertas a un abordaje multiprofesional. Defendemos la necesidad de apostar por la recuperación de las personas con trastorno mental severo desde una vertiente socioeducativa, más allá del planteamiento médico-clínico. Se revisa la bibliografía y analizan los resultados de diversos programas de apoyo a la vivienda como eje central de intervención en la comunidad. Se evidencia un mejor funcionamiento personal y social, menor número de ingresos, mayor satisfacción y calidad de vida a menor coste económico. Es crucial la configuración de una política pública de acción social que promueva las condiciones necesarias para conseguir una justicia social y una ciudadanía inclusiva. Se concluye la relevancia de la Pedagogía Social y la Educación Social en la consecución de este objetivo y en la mejora de la calidad de vida. Reivindicamos su propio espacio teórico-práctico en el ámbito de salud mental.

Palabras clave: enfermedad mental; vivienda; integración social; intervención socioeducativa; justicia social

Introduction

Nowadays the consideration of “citizen” granted to an individual with a mental disorder produces a change in the way their needs are addressed, offering a range for possibilities of multidisciplinary attention. This conception, more philosophical than an actual practice, has guided the proposal to transform psychiatric attention as of the second half of last century, with diverse variants however, in the United States, various European and Latin American countries. In this paradigm, the pedagogical dimension has to become an indispensable element for the social inclusion of individuals with a severe mental disorder (SMD) in the community.

In this process, from our standpoint, supported residential and accommodation services arises as one the basic pillars in the recovery and social inclusion of people with mental disorders, up to the point that a number of authors such as Shepherd and Murray (cited in Macpherson et al., 2004: 180) state that “housing shall be in the center of communal psychiatry”.

Then we present some key socio-educational issues that move to reflection on SMD attention and housing programs. In the first place, the importance implied by the change in the health care model in Spain is distinguished; it change from a purely therapeutic and clinical conception under an institutional model to a holistic, communal and civil, paving the road for an inter-sectoral approach (Prieto-Rodríguez, 2002).

In like manner, there is an account of the needs of people with SMD and the various scopes of pedagogic intervention; finally, housing is considered the central axis of such intervention owing to the positive effects that it produces in its users, providing necessary individuated support in function of the multiple personal and social needs of the residents. Therefore, the objective of the present work is to show the relevance of socio-educational work in the recovery of people with SMD, and also its importance in social policies that should enforce it. Without this socio-educational vision, from all administrative, political and labor levels, the intended social integration is left incomplete, vindicating a policy based on social justice.

Attention to severe mental disorder in Spain: a pedagogic issue?

Historically, the concept of mental disorder has experienced some significant changes, from which several clear implications in terms of policies and attention strategies that demanded and nowadays demand large-scaled organizational changes come out. Well into the XIX, insanity was considered a social problem and an issue of public order, whose treatment was reclusion (Foucault, 1976). Later on, insanity came to be considered a disease, and as such, a medical issue, turning lunatic asylums into psychiatric hospitals. However, the custodial function still prevailed over therapeutic treatment (Rodríguez, 2002).

Along the XX century, voices critical to the institutional model arise and call for a transformation; even the origin and cause of mental disorders is discussed, generating a number of trends of thought that have repercussions on the attention to such disorders. On the one side, we find a hegemonic biomedical model, in which a psychiatrist diagnosis is the result of a clinical judgment based on a cerebral approach to metal disorders, with a biological etiology and whose treatment techniques are pharmacological in nature (Cea-Madrid, 2015; Geneyro and Tirado, 2015).

On the other side, one finds the current from the so called antipsychiatry of the 1960’s and 70’s, in which authors such as Cooper, Laing, Basaglia, Oury or Szasz state the hypothesis of the social origin of mental disorder, this way they characterized mental disorders, in short schizophrenia, as a relational problem, not organic; this is to say, as a disorder derived from the subject’s adaption to their social environment (Cea-Madrid and Castillo-Parada, 2016; Desviat, 2006; Morales, 2012; Pastor and Ovejero, 2009) to the point of denying the existence of metal disorders and using the mental disorder as a social mechanism, regulated and ruled by psychiatry in order to pathologize human heterogeneity (Vásquez-Rocca, 2011).

This way, loaded with theoretical and political elements, the 1960’s-70’s “classic antipsychiatry” established a denounce of psychiatry’s power and function in society as a theoretical-political movement with clear social and political claims and justifications (Cea-Madrid and Castillo-Parada, 2016) and at a sociohistorical time loaded with various social, ideological, unionist, cultural and political claims.

Therefore, if pathology has its origin in the familial and community context the subject lives in, it is there where therapy must take place, not in hospital contexts (Pastor and Ovejero, 2009). These winds of change were important as they generated a new attention model for people with mental disorders, which progressively evolves from the clinical treatment of the disorder to the integral attention of the community itself, emphasizing their status as citizens with rights and duties (López and Laviana-Cuetos, 2007).

This evolution comes into force in Spain by the mid 1980’s with the process of psychiatric reform started in 1985 with the Report of the Ministerial Commission for the Psychiatric Reform, concurring at a historic moment of deep transformations in all the spheres and tiers of Spanish society (Desviat, 2000).

From that moment on, the process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization began and the community care model is assumed. Its objective is to articulate attention to these people’s psychiatric problems in their own socio-communitarian environment, empowering the remaining and integration in the familial and social context in the most normalized possible way (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo [MSC], 2007).

This way, the ideal framework to assist mental disorders is not a closed institution but the community, hence it is intended to potentiate the individual’s autonomy as pedagogy’s central objective (Rosendal, 2013). Nowadays, the new international approaches to care emphasize the concept of recovery (Anthony, 2000; Scheyett et al., 2013), which refers not only to recover from the disorder, but also the retaking the vital project once the disorder and disability appear (Garrido et al., 2008).

From this standpoint, education acquires vital importance, as it is recognized as a fundamental right that it has to enable both citizens’ participation in economic, political and cultural life, and the educative treatment of the effects, in the form of vulnerability, inequality, exclusion, marginalization and social maladjustment that current society produces (García Molina, 2003).

On the other side, over this period and up to the present, a number of documents and guidelines have been developed to definitively foster the setting up of this social inclusion model for people with severe metal disorders (SMD), both at national and international level.

Among them we can refer: the Declaration of Helsinki and the Plan of Action 2005; Green Paper - Improving the mental health of the population: Towards a strategy on mental health for the European Union, 2005; the “European Pact for Mental Health and Well-being”, 2008, important to fight against social exclusion and stigma; or World Health Organization’s Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (2013-2020).

However, in the analysis of reality one can verify not only the forgetting and absence of pedagogical proposals in the definition of social policy on mental health and SMD, but also that a sizeable part of these documents have remained mere guidelines without being implemented. Moreover, the actual setting up of the communitarian model has had its chiaroscuros (Espino, 2002), focusing efforts on reorganizing and restructuring the health care system, but with a deficient supportive network (few places adapted to the various needs, lack of labor insertion programs, lack of community programs for social integration).

Adding to this, Public Administration has diluted a large share of its responsibility into the associative instances that are now experiencing liquidity problems, due to delays in payments, uncertainty on the continuity of agreements and the dismantling of the Law of Promotion of Autonomy and Attention to People in Dependency Situation, etc. (Pérez and Navarro, 2013).

This way, we shall make it clear the connection of public policies with the socioeconomic context of each time. From here, this initial impulse in the 1980’s, characterized by a moment of profound transformations in Spanish society; and also from here, the scant later coverage of the community model. Hence, the current economic policies, liberal in nature, challenge the criteria that made the Europe of Welfare possible, prioritize the reduction social expenditure and the contention of public expenditure growth by means of policies of budgetary restriction and privatization of State-provided services (Espino, 2002; Desviat, 2011).

This way, in the economic and political context restrictive for public health care especially affects mental health, tail-end of the collectives with socio-sanitary needs (Espino, 2002), and the true Cinderella for health care systems and social services so that families and people with mental disorders are at great risk of social exclusion; this way, we have to agree with Foucault (1976) when he makes us think that in all the psychiatric reforms that have taken place over the last two centuries, the criterion of exclusion has remained, changing shape and place.

This new philosophy of attention must place us before challenges and demands which have to be addressed so that social realities are improved from a holistic perspective, not restricted only to the clinic-psychiatric sphere (Dimenstein et al., 2012). In this context, Social Pedagogy shall maintain active its capacity to promote processes of learning, training and development, with vocation for change and social transformation that decisively contribute to the well-being of people and improve their quality of life (Caballo and Gradaílle, 2008).

Hence, the desire of transforming the social conditions of existence from, with and for society is made explicit (Caride, 2002 and 2005); there has to be substantial modifications in relation with the place people take in social action processes, being subjects of action and not only objects to apply policies rather paternalistic, in such manner that social education, in words by Ortega-Esteban (1999: 18) , “above things shall help to be and coexist with the others. Learn to be with the rest and live together in community”.

The importance of social education in social policies is also reaffirmed, as it guides the pedagogic activity toward the dynamization of communal resources, such as housing, compensation for inequalities, facing social inclusion issues that people with SMD experience, as well as the search for new possibilities for their integration and social insertion and the development of democratic coexistence (Caride, 2005).

Moreover, attention to people with SMD not only shall encompass the vision of Pedagogy/Social Education to palliate and improve the situations that come from marginalization and social exclusion, as it is being carried out nowadays, but also suggests the existence of an intervention based upon the reciprocity that has to be established between the education’s social dimension and the society’s educational mission (Caride et al., 2015).

Hence, “it will be fundamental that Social Education articulates its proposal around two processes, which should be considered indissoluble and starting and arrival point: communitarian construction and democratic participation” (Caride, 2002: 107 ); both aspects are present at the new philosophy of attention to people with SMD, but which only by means of the socio educational sphere can be fully implemented. Because of this, we propose the community as a space for social intervention, where citizens broaden their leadership as a reflection of their collective action; they gradually build their own discourse on what is necessary to transform, they search for ways and social processes that work as models for their actions and answers to their needs.

This way, community action becomes meaningful when it is developed from a human collective that shares a space and a sense of belonging, which produces bonding and mutually supportive processes and which activates protagonist willingness in the improvement of their own reality (Gomá, 2008). Such actions are fundamental in the frame of socio-educational work for an actual recovery from severe mental disorder.

Therefore, at this point two lines concur, so far they seemed to be installed in the collective and professional imaginary as parallel and differenced, which never connected, namely: attention to SMD and Social Pedagogy.

Severe mental disorder: concept, necessities and main spheres of pedagogical intervention

Inside this whole new paradigm of community attention, one finds people with SMD. The concept, assumed by the majority of policies and global documents on mental health, is based on the conjunction of three dimensions that make its definition operational (MSC, 2007; Liberman, 1993; Ruggeri et al., 2000):

Diagnosis, which usually includes, fundamentally, schizophrenia and other psychoses and delusional disorders (the largest diagnosis group), affective psychoses, and some sorts of personality disorders.

Duration and treatment, generally over two years.

Global functioning and presence of disability, implying alterations and deficits in a number of functional aspects such as social behavior, interpersonal relationships, self-care, autonomy, leisure and free time, accommodation and employment.

These dimensions are virtually present in the totality of the literature reviewed. However, López and Laviana (2007) express the need to add another dimension of contextual character, stigma, one of the most important causes of limitation and social restriction, defined as “a mark of shame, dishonor, disapproval because of which the subject is rejected, discriminated and excluded from the participation in diverse spheres of society” (OMS, 2001: 16).

People with SMD suffer heavy stigmatization and discrimination (Whitley and Campbell, 2014). Such stigma ends up being as handicapping or more than the very symptoms of the disorder; this way, attitudes of rejection toward these people and the social negative consequence can create additional barriers that increase their risk of isolation and marginalization.

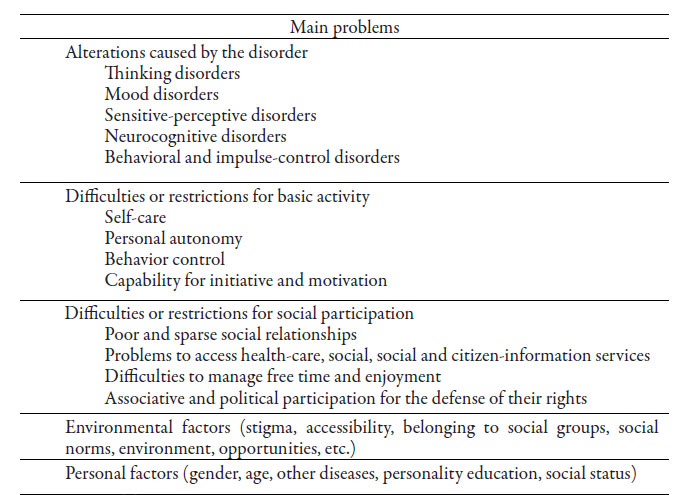

Because of this, socio-communitarian support is fundamental, demonstrating that low levels of social support are linked to higher stigmatization levels and lower levels of quality of life (Chronister et al. 2013). Thereby, as exposed by Garcés Trullenque (2010), their problems and needs overstep the sanitary-psychiatric sphere and express in social aspects: difficulties or restrictions for basic activities and social participation; environmental and personal factors that translate into a poor quality of life (see table 1).1

Out this of sort of problems, there comes a series of needs that configure the main areas of socio-educational action, always within the scope of community, as a support for integration, accommodation and residential attention; labor integration, leisure and free time activities, as shown in Table 2.

All in all, the objective we have set is that they can recover their vital project, for which the community acquires a fundamental value in the context of intervention. This supposes a change toward the participation of various agents, mainly socio-educational and whose key referent is emancipation and social transformation, and it is here where education is closely linked to community development (García-Pérez, 2013a).

The intention is to have a community environment favorable for the acceptance of the disabilities conveyed by the disorder and propitiate the optimization of available resources in the community, and in this we the socio-educational professionals have a primary role (García-Pérez and Torío-López, 2014a).

Hence, this dimension of the global function of SMD underscored by WHO (2001), it is the one, which to a good extent, determines the differentiation in the ways of intervention and distinctions between a patient and another sane individual who needs a series of socio-communal support. On this issue, the international community and the Spanish State promote a number of initiatives oriented to foster equating policies.

Especially important is UN 2006 “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities”, whose intention is to accomplish the full development of disabled people, by means of the exercise of their social, cultural, civil and political rights. In Spain, following the postulates of the Convention, the “Spanish strategy on Disability, 2012-2020” was produced as a formula to collaborate to the full autonomy and inclusion in the collective. But once again, reality shows us a community in which SMD is not associated with functional diversity, but with a disorder that has to be treated under medical parameters, not from a provision of support from social welfare.

Because of this, actuations of social inclusion into the community are not possible if people with SMD do not actually live in the community. Therefore, facilitating accommodation is the first basic element for intervention to act, offering in the first place, residential stability according to the choices and preferences of the users and from here, establish the adequate vital, educational, labor, social and leisure supports.

Supported accommodation as an essential base for recovery

Housing is a basic human and universal need, it is the environment in which more daily care routines and social, familial and intimate relations are comprised, this way the feeling of home is crucial for every citizen’s positive mental health. People with SMD face the same housing problems as other community groups. However, their situation may be insecure or precarious, with serious difficulties to access and maintain a decent housing adequate for their demands and desires.

As stated by Ridgway (2008), people with psychiatric disabilities have a risk ten times higher than the general population to become homeless. In this circumstance, several factors come into play (López Álvarez et al., 2004; Nelson, Aubry and Hutchinson, 2013; Ridgway, 2008): difficulty in searching, accessing and maintaining a house; discrimination motivated by the stigma that accompanies mental disorders; insufficient economic incomes; insufficient social planning in the context of the deinstitutionalization policy, which becomes inadequate or limited organization of community residential services.

Moreover, not having adequate housing generates a series of negative consequences facing the attention and integration of people with SMD into the society and community and also affects the whole model of health care and social assistance: increment of hospital readmissions; excessive familial burdens; difficulties of community integration; increment of people with SMD in homeless marginalization (Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría [AEN], 2002; Rodríguez, 2002).

This way, the acquisition of decent housing provides an inflection point that allows people start working in their recovery and then, accomplish other objectives in their lives (Ridgway, 2008). In like manner, as stated by Rogers et al. (2009), apart from the treatment, probably there is no other service area more important for the recovery of people with SMD than housing services.

This way, the creation and development of these accommodation devices has experienced an evolution that goes from halfway houses, with important therapeutic and rehabilitating content, to the philosophy called supported housing, which the model of residential attention, nowadays considered the global reference due to the evidence of its results, is based upon. Namely, housing first and the program “Pathways to Housing Program” developed by Tsemberis and Eisenberg (2000) in New York and that is in use across the US and in some European countries such as Denmark, Finland, France and Sweden (Pleace and Wallace, 2011).

Evolution of residential attention for people with severe mental disorder

Over the last 30 years there has been a boom of household services and models of provision of services fostered by deinstitutionalization and the intention to integrate people with SMD into the community. Usually, residential programs have witnessed a similar evolution, which we can present in three successive phases (Fakhoury et al. 2002; López et al. 2004; Nelson, 2010; Nelson et al. 2013; Newman, 2001; Ridgway, 2008; Rogers et al. 2009).

In the first place, halfway houses are created; these can serve to make the change to community life, prolonging health care attention with therapeutic and rehabilitating content, within a custodial attention model. In relation to this model, it was demonstrated that it hindered independent social functioning, increasing assisted activity (Segal and Kotler, 1993) and producing fewer personal benefits of participation and independence than other accommodation with broader community support (Nelson et al., 1998).

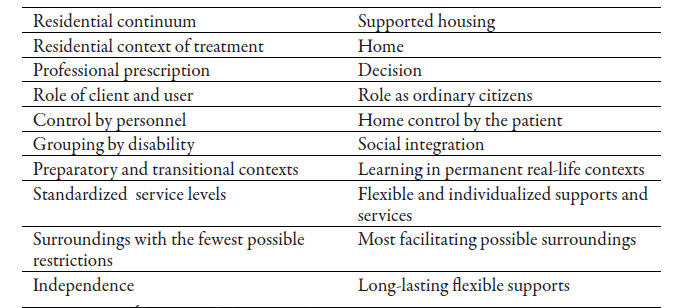

Later on, the programs start to become independent from health care networks, at the same time they adopt a structure that combines various alternatives graduated according to supervisions and support levels, in which the users go through more than ten different devices (Carling, 1993; López et al., 2004; Ogilvie, 1997). This is the model known as “residential continuum” or “linear continuum”. It was about articulating a sort of scaffolding of intermediate resources between hospital and the community to offer services based on a prototypical functioning according to the patients’ functional profile (Ridgway, 2008) in order for them to reach independent life. Criticisms to this philosophy of residential attention underscore the scant margin left for the users’ initiative and preferences, and also the difficulties generated by making the mobility that substantiates the model effective (Geller and Fisher, 1993; Nelson et al., 2013; Ridgway, 2008; Ridway and Zipple, 1990). However, it is still the most characteristic model in residential attention for people with SMD.

These criticisms to the linear model produced the arrival, basically in the United States and about a decade ago, of a third perspective and an alternative model called supported housing; it is a flexible and continually supported system in which people with SMD exercise the control of their household that responds to their choices and preferences. This programs offers in the first place subsidized, stable and permanent housing before any other intervention, and then it combines this with other services and supports individualized on the basis of the patients’ needs (Tsemberis and Eisenberg, 2000).

Although its good results are distinguished, some authors consider that it is a model reduced to assist the poor and the homeless (Desviat, 2011), whose main political motivation to be set up is to reduce costs (Stanhope and Dunn, 2011). In this case, the basic ideas or principles that support the model include a series of elemental needs such as a having a house, which they can choose according to their preferences to have control of their activities and lifestyle, etc. (López et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 2013; Ridgway, 2008; Ridgway and Zipple, 1990) (see table 3).

In this regard, few studies have directly compared these models; even those existing do not clarify evidence and differential results (Goldfinger et al., 1999). Other studies, such as those by Tsemberis and Eisenberg (2000) or Siegel et al. (2006), show better stability in the household, greater autonomy and higher satisfaction levels, higher participation in the community and reduction of symptoms in the users of supported housing, as they make their preferences effective (Nelson, 2010; Rogers et al., 2009). Thereby, well-being levels improve as the restriction levels of the house decrease, which also produces a lower economic cost (Pleace and Wallace, 2011).

Results of accommodation programs with support for people with SMD

Scientific literature on supported accommodation for people with SMD verifies the limits of evidence and the general lack of solid proof in the sector (Chilvers et al., 2010; Fakhoury et al., 2002; O’Malley and Croucher 2005).2 In spite of this, there is sufficient information to state that various residential programs are associated with positive results for people with SMD (García-Pérez and Torío-López, 2014a; Hubley et al., 2014; López et al., 2004; Nelson, 2010; Nelson et al., 2013; Newman, 2001; Pleace and Wallace, 2011; Pleace and Quilgars, 2013; Ogilvie, 1997; Rogers et al., 2009; Ridgway, 2008; Tsemberis, 2010). We distinguish, among others, the following:

They are capable of keeping a considerable number of people with SMD in the community

They offer certain residential stability.

They improve social functioning and integration.

They reduce the incidence of hospitalization and psychiatric symptoms.

They increase the level of basic and social functioning (better performance of social activity and daily life routines).

They improve the bonds with community resources.

They raise self-satisfaction.

They increase the quality of life and produce a deep sense of home and belonging.

They are profitable: they reduce costs due to a reduced use of service, patients improve their health, they are more satisfied with their vital state, which produces a lower number of hospital admissions and, in the case, days hospitalized are fewer, etc.

Naturally, these results depend on different variables associated to accommodation: location of the house, functions and services offered; temporary or permanent accommodation; number and characteristics of supportive personnel; open or restrictive environment; resources of the environment; neighbors’ reticence, etc. Hence, it has been demonstrated that the fact of residing in low quality or inadequate housing increases the risk of activity deterioration, reduces the quality of life and raises the number of hospital readmissions (Fakhoury et al., 2002).

Therefore, housing and the supports offered therein are crucial elements in the recovery of people with SMD and their social insertion, since they have positive or negative consequences in function of the patients’ choice or preference and the sort of program implemented in them.

As a conclusion

Changes in the way mental disorders are perceived, and thereby, the approach to their necessities and problems make it evident the need to perform a pedagogic intervention, in the context of community attention. However, from the analysis of the current reality, the forgetting and absence of socio-educational proposals in the definition of social policy on mental health and severe metal disorders can be verified.

Moreover, the actual setting-up of the community model has been left half-finished, putting aside the social and the educational, community, labor, and residential support and insisting on a clinical model in which large part of the “social” programs intended for these people and /or their families come from mental health services. This way, one must shy way from partial solutions and treatments and take global and holistic actions, as Desviat (2011: 292) expresses:

The community is not rotation between mental health centers […] nor is it an attention program for the poor, as it has been reduced to in the United States […], the community is interconnected work, action in a territory in continuous interaction with citizens and their organizations. Citizenry that is part of the processes, that makes the assistance process its own.

If the integration of people with severe mental disorder into the community is a fundamental principle, value and goal of contemporary mental health (Wong et al., 2011), housing emerges as the main support for integration and recovery management.

On the one side, it has been demonstrated that they are effective rehabilitating resources that improve clinical aspects and basic functioning, but also increase the quality of life and strengthen sense of community belonging and social relationships. On the other, the fact that the very patients perceive improvement is of the utmost importance, as it increases their self-esteem and self-confidence to carry out any activity, being assured they have a house and the necessary supports to do so.

This way, the ultimate goal of residential services for people with SMD is to serve as a starting point to accomplish a change in role from “client” to citizen by means of housing (Newman and Goldman, 2008) and also by means of education and employment opportunities (Piat and Sabetti, 2010).

However, not only is it a resource in which direct intervention may be the link to the rest of community services, but also directly places the individual in the community, in a neighborhood on which to lay the foundations for civil participation so that joint work is undertaken as a symbiosis of citizenship foment, improving not only their personal situation, but also reducing the stigma, eliminating negative labels from society. This becomes the reduction of social rejection and directly improves their social inclusion, and successively, in a cycle of mutual improvements generated by such community construction.

In order to build that “community recovery cycle”, in the first place, it is necessary to set up public policies that actually back stable housing support, as well as coordinated educational, health care and labor systems that guarantee universal and equitable services, in which complementariness and collaboration, not competence and lack of solidarity, act together (Desviat, 2011).

This claim seems to become a utopia at a time of social cutbacks and dismantling of the Welfare State in the European context, whose two main foundational principles, solidarity and social citizenship (Román-Brugnoli et al., 2014), are crumbling down. This way, the social effects of the crisis in Spain are rather noticeable both from the individual and collective standpoints, increasing the risk of social fracture.

The economic crisis leads to increasing social needs related to employment, housing, income and food and especially affects those in worse poverty situations and social exclusion and also people with SMD (García-Pérez, 2013b). Before this panorama, many people with SMD live in chronic poverty and do not have the necessary resources to access decent housing.

This often forces the individuals to resort to the shelter system or to live on the street (Nelson et al., 2013; Ridgway, 2008), so their attention shall be emphasized in a multidimensional way: social, economic and environmental (Martínez-Treviño et al., 2014). If this dire situation of people with SMD is not enough to set up these supportive systems, maybe in a neoliberal context such as the current, the fact that, for instance, supportive housing reduces costs of public services is a sufficient reason to undertake it, as it was the case of Housing First in the United States (Stanhope and Dunn, 2011).

Furthermore, we have to transcend the concept of citizenship that is promoted from the public policies of attention to SMD, which in practice is based almost entirely on the conception of legal status and not on the actual possibility of exercising certain duties and rights, following the public questioning to the capacity of modern Nation-States to offer effective and equal opportunities for their citizens (Gómez-Urrutia, 2014; Nussbaum, 2011). Scarcely worth is the proliferation of legislation, recommendations and strategies — previously stated—, if they are not accompanied by resources and personnel, added by a modification of the social and cultural structure, securing minimum levels for all the citizens.

All in all, not only is a palliative change necessary, which is what has occurred, to improve an existing system, largely related to health care and rehabilitation, but also a transforming change. Following Nelson’s (2010) proposal, people with mental health problems should be not only in community, but be valuable members of it.

This new position demands a concept of civil citizenship that promotes conditions for equal opportunities and access and for treatment in the public space and institutions; inclusive citizenry that promotes social justice facilitating the incorporation of people with SMD so that their interests are represented, their rights respected and their individual and collective needs addressed.

Being aware of the impossibility of providing limitless resources, public policies should guarantee a broad range of alternative housing services, once its positive effects are demonstrated, as a housing basic right beyond therapy, in addition to recognize its lower cost in relation to the current medical attention system.

This way, the development of this paper demonstrates the concurrence of the necessary foundations that justify a socio-educational intervention in a number of areas, recreating scenarios of pedagogic action in a population sector heavily stigmatized.

Therefore, housing is the element on which actions to undertake as a community, in a coordinate and integral manner, are supported; it has a wide range of possibilities focused on various supports, in function of the needs and demands of people with SMD and their preferences:

Community development and civil-social education: with interventions in the autonomy of the community and unfolding in the environment, programs in coexisting, family, partner, etc. In this section we can include any element that favors social participation and work aimed at eradicating the stigma and social degradation suffered by people with SMD. This way, every community interaction can generate positive or negative answers so that many interactions can provoke stress, anxiety and be harmful for the development of severe mental disorders, thus an avoidance answer is propitiated. Reaching this point, patients can assimilate what Corrigan et al. (2009) called the model of “Why try?” The model suggests that as a result of the internalized stigma, people with SMD can lower their self-esteem and self-efficacy, which might prevent them from accomplishing their vital objectives. Thereby, people with SMD who are aware of the mental disorders’ public stigma and take up these stigmatizing attitudes can doubt their capability to participate in community and accomplish social inclusion (García-Pérez and Torío- López, 2014b). Educational support: in reference to programs with a supportive formal-education component such as supported education by Mowbray et al. (2005), with great results in accomplishing higher education for people with SMD and that directly becomes the patients’ personal and social improvements.

Occupational-training and labor insertion support: with actions intended to develop their vocational orientation, the basic habits to adjust to the labor environment, training support for all sorts of non-formal education, which link with the concept of learning for life, training to look for a job, obtain and keep the post, insertion into the regular labor market, supported employment, protected employment, etc. All of these aspects imply formative work with the entrepreneurial sector, the community and the context in which actions take place, which turn into improvement of communicational and social abilities, strengthening of social networks, with interventions in the sphere of autonomy in the community and interaction in it, while they adequately use their free time.

Leisure and sociocultural entertainment: in this case we have to offer these people “normalized leisure”, which also needs certain training to choose and enjoy, giving them personal resources by means of various socio-educational activities in full integration with the community’s resources. Leisure becomes a channel for participation, a socializing element to learn cultural values and cohesion, and also a source and momentum for community transformation. Moreover, its influence on the recovery of people with SMD has been demonstrated (Iwasaki et al., 2014).

In order to achieve these goals, it is essential to work in and with the community, in and with the neighborhood, the environment and the city. The city and neighborhood where they live turns into a rehabilitating and educational agent in which human being has to constantly face new situations difficult to anticipate. In this context, social education promotes didactical strategies that foster autonomy so that relationships that occur in people’s daily life are, at the same time vehicles, contexts and contents of socio-pedagogical actions (Úcar, 2013).

This way, education must be an instrument to help and address the quotidian and concrete needs of the population, turning society into an enormous formative potential, as a place of cultural interchanges and a school of civism, democracy, solidarity and participation (García-Pérez and Torío-López, 2014b). Therefore, we have to rethink social pedagogy and the generation of new approaches that suit better the complex current reality; the natural field of intervention is the people’s quotidian life, not a specific institution.

This way, Social Pedagogy can also help people with SMD; advise, guide and support empowering processes that give them resources to improve their quality of life. Because of this, aid for supported housing has to be individualized in function of the preferences and needs expressed by people with SMD, in joint decision making and between the patient and the socio-educational professional, setting up participatory methodologies in mental health (Cea-Madrid, 2015).

Finally, the configuration of a policy of social action and welfare with these characteristics needs a number of perspectives, as it has been demonstrated, among which the pedagogical dimension is basic and fundamental (March, 1988). This way, a new action frame opens, both from the theoretical and practical standpoints, and the relevance of Social Pedagogy and Education in the task of rehabilitating these people and in the improvement of their welfare and quality of life is verified by means of socio-educational actions which have housing a central element.

REFERENCES

Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría (AEN) (2002), Rehabilitación psicosocial del trastorno mental severo. Situación actual y recomendaciones. Cuadernos Técnicos, núm. 6, España: Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría. [ Links ]

Anthony, William A. (2000), “Recovery-oriented service systems: setting some system level standards”, en Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, vol. 24, núm. 2, Estados Unidos: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Caballo, Belén y Rita Gradaílle (2008), “La educación social como práctica mediadora en las relaciones escuela-comunidad local”, en Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, núm. 15, España: Sociedad Iberoamericana de Pedagogía Social (SIPS). [ Links ]

Caride, José A. (2002), “La Pedagogía Social en España”, en Núñez, Violeta [coord.], La educación en tiempos de incertidumbre: las apuestas de la Pedagogía Social, España: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Caride, José A. (2005), Las fronteras de la Pedagogía Social, España: Gedisa . [ Links ]

Caride, José A. et al. (2015), “De la pedagogía social como educación, a la educación social como pedagogía”, en Perfiles Educativos, vol. XXXVII, núm. 48, México: ISUE-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Carling, Paul J. (1993), “Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice”, en Hospital and Community Psychiatry, vol. 44, núm. 5, USA: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Cea-Madrid, Juan Carlos (2015), “Metodologías participativas en Salud Mental: alternativas y perspectivas de emancipación social más allá del modelo clínico y comunitario”, en Teoría Crítica de la Psicología, núm. 5, México: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. [ Links ]

Cea-Madrid, Juan Carlos y Tatiana Castillo-Parada (2016), “Materiales para una historia de la antipsiquiatría: balance y perspectivas”, en Teoría Crítica de la Psicología, núm. 8, México: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo . [ Links ]

Chilvers, Rupatharshini et al. (2010), “Supported housing for people with severe mental disorders (Review)”, en Cochrane Schizophrenia Group, núm. 12, Chichester, Reino Unido: Wiley. [ Links ]

Chronister, Julie et al. (2013), “The role of stigma coping and social support in mediating the effect of societal stigma on internalized stigma, mental health recovery, and quality of life among people with serious mental illness”, en Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 41, núm. 5, USA: Wiley. [ Links ]

Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas (2005), Libro Verde Mejorar la salud mental de la población. Hacia una estrategia de la Unión Europea en materia de salud mental. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_determinants/life_style/mental/green_paper/mental_gp_es.pdf [14 de julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

Corrigan, Patrick W. et al. (2009), “Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices”, en World Psychiatry, vol. 8, núm. 2, Ginebra: Wiley. [ Links ]

Desviat, Manuel (2000), “La asistencia de las psicosis en España o hacia dónde va la reforma psiquiátrica”, en Rivas Guerrero, Fabio [coord.], La Psicosis en la Comunidad, Madrid: Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría. [ Links ]

Desviat, Manuel (2006), “La antipsiquiatría: crítica a la razón psiquiátrica”, en Norte de Salud Mental, núm. 25, País Vasco: Osasun Mentalaren Elkartea, Asociación de Salud Mental. [ Links ]

Desviat, Manuel (2011), “Panorama actual de las políticas de bienestar y la reforma psiquiátrica en España”, en Estudos de Psicologia, vol. 16, núm. 3, Brasil: Scielo. [ Links ]

Dimenstein, Magda et al. (2012), “Participación y redes de cuidado entre usuarios de servicios de salud mental en el nordeste brasileño: mapeando dispositivos de reinserción social”, en Psicología desde el Caribe, vol. 29, núm. 3, Colombia: Universidad del Norte. [ Links ]

Espino, Antonio (2002), “Análisis del estado actual de la reforma psiquiátrica: debilidades y fortalezas. amenazas y oportunidades”, en Revista AEN, vol. XXII, núm. 81, España: Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría . [ Links ]

Fakhoury, Walid K. H. et al. (2002), “Research in supporting housing”, en Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, vol. 37, núm. 7, USA: Springer. [ Links ]

Foucault, Michel (1976), Historia de la locura en la Época Clásica, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Garcés Trullenque, Eva María (2010), “El Trabajo Social en Salud Mental”, en Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, núm. 23, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

García-Molina, José (2003), “Educación Social: ¿profesión educativa o empleo social?”, en De nuevo, la Educación Social, Madrid: Dykinson. [ Links ]

García-Pérez, Omar (2013a), “Viviendas supervisadas para personas con trastorno mental severo en Asturias: ¿ambiente restrictivo o abiertas a la comunidad?”, en Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, núm. 22, España: Sociedad Iberoamericana de Pedagogía Social. [ Links ]

García-Pérez, Omar (2013b), “El rol del ciudadano de la persona con trastorno mental severo: preferencias y poder de elección sobre la vivienda”, en Torío-López, Susana et al. [eds.], La Crisis Social y el Estado de Bienestar: las respuestas de la Pedagogía Social, España: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Oviedo. [ Links ]

García-Pérez, Omar y Susana Torío-López (2014a), “Funcionamiento básico y social de los usuarios de las viviendas supervisadas para personas con trastorno mental severo en Asturias: necesidad de una intervención pedagógica”, en Revista Complutense de Educación, vol. 25, núm. 2, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid . [ Links ]

García-Pérez, Omar y Susana Torío-López (2014b), “Alojamiento con apoyo para personas con trastorno mental severo: ¿Participan realmente en la comunidad?”, en Del Pozo-Serrano, Francisco José y Carlos Peláez-Paz [coords.], Educación Social en situaciones de riesgo y conflicto en Iberoamérica, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid . [ Links ]

Garrido et al. (2008), “Buscando la reconstrucción personal, retomando el control de la propia vida. Un diseño para favorecer procesos de “recovery” y “empowerment”, en Informaciones Psiquiátricas, núm. 194, España: Hospital Benito Menni. [ Links ]

Geller, Jeffrey L. y William H. Fisher (1993), “The linear continuum of transitional residence: debuking the myth”, en American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 150, núm. 7, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Geneyro, Silvia Carolina y Francisco Javier Tirado (2015), “Diagnóstico clínico en biopsiquiatría: de la hermenéutica clínica a la traducción psicofarmacológica”, en Sociología y Tecnociencia, vol. 4, núm. 1-2, España: Universidad de Valladolid. [ Links ]

Goldfinger, Stephen et al. (1999), “Predicting homelessness after rehousing: A longitudinal study of mentally ill adults”, en Psychiatric Services, vol. 50, núm. 5, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Gomá, Ricard (2008), “La acción comunitaria: transformación social y construcción de ciudadanía”, en RES. Revista de Educación Social, núm. 7, España: Asociación Estatal de Educación Social. [ Links ]

Gómez-Urrutia, Verónica (2014), “Modelos de ciudadanía: discursos sobre roles femeninos en la legislación chilena”, en Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 66, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Hubley, Anita M. et al. (2014), “Subjective quality of life among individuals who are Homeless: a review of current knowledge”, en Social Indicators Research, núm. 115, Nueva York: Springer. [ Links ]

Iwasaki, Yoshitaka et al. (2014), “Role of leisure in recovery from mental illness”, en American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, vol. 17, núm. 2, Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Liberman, Robert Paul (1993), Rehabilitación integral del enfermo mental crónico, España: Martínez Roca. [ Links ]

López-Álvarez, Marcelino et al. (2004), “Los programas residenciales para personas con trastorno mental severo. Revisión y propuestas”, en Archivos de Psiquiatría, vol. 67, núm. 2, España: Tricastelia. [ Links ]

López-Álvarez, Marcelino y Margarita Laviana-Cuetos (2007), “Rehabilitación, apoyo social y atención comunitaria a personas con trastorno mental grave. Propuestas desde Andalucía”, en Revista AEN, vol. XXVII, núm. 99, España: Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría . [ Links ]

Macpherson, Rob et al. (2004), “Supported accommodation for people with severe mental illness: a review”, en Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, núm. 10, Reino Unido: Royal College of Psychiatrists. [ Links ]

March, Martí Xavier (1988), “La intervención pedagógico-social en el ámbito de la inadaptación social: hacia una pedagogía de la inadaptación social”, en Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, núm. 3, España: SIPS. [ Links ]

Martínez-Treviño et al. (2014), “El referente de la pobreza en el discurso de la ONU sobre el desarrollo sostenible”, en Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 66, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México . [ Links ]

Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad (2012), Estrategia Española sobre Discapacidad 2012-2020, Madrid: Gobierno de España. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/espana/eh14/social/Documents/estrategia_espanola_discapacidad_2012_2020.pdf [14 de julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

MSC (2007), Estrategia en Salud Mental del Sistema Nacional de Salud , 2006, España: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. [ Links ]

Morales-Ramírez, Francisco (2012), “La recepción de la antipsiquiatría en México entre las décadas de 1970 y 1980”, en Temas de Historia de la Psiquiatría Argentina, vol. XV, núm. 31, Argentina: Polemos. [ Links ]

Mowbray, Carol T. et al. (2005), “Supported education for adults with psychiatric disabilities: an innovation for social work and psychosocial rehabilitation practice”, en Journal of Social Work, vol. 50, núm. 1, Reino Unido: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Nelson, Geoffrey (2010), “Housing for people with serious mental illness: approaches, evidence, and transformative change”, en Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, vol. XXXVII, núm. 4, USA: Western Michigan University. [ Links ]

Nelson, Geoffrey et al. (1998), “The relationship between housing characteristics, emotional well-being, and the personal empowerment of psychiatric consumer/survivors”, en Community Mental Health Journal, vol. 34, núm. 1, Nueva York: Springer . [ Links ]

Nelson, Geoffrey et al. (2013), “Housing and Mental Health”, en Stone, J. H. y M. Blouin [eds.], International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/132/ [13 de enero de 2013]. [ Links ]

Newman, Sandra (2001), “Housing attributes and serious mental illness: implications for research and practice”, enPsychiatric Services , vol. 52, núm. 10, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Newman, Sandra y Howard Goldman (2008), “Putting Housing First, Making Housing Last: Housing Policy for Persons with Severe Mental Illness”, en American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 165, núm. 10, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Nussbaum, Martha (2011), Creating capabilities, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Ogilvie, Rita J. (1997), “The state of supported housing for mental health consumers: A literature review”, en Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, vol. 21, núm. 2, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

O´Malley, Lisa y Karen Croucher (2005), “Supported housing services for people with mental health problems”, en Housing Studies, vol. 20, núm. 5, Reino Unido: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

OMS (2001), Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento, de la discapacidad y de la salud: CIF, España: Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales. [ Links ]

OMS (2005), Mental Health: Facing the Challenges, Building Solutions: report from the WHO European Ministerial Conference of Helsinki, Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.msssi.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/excelencia/salud_mental/opsc_est17.pdf.pdf [14 de julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

OMS (2008), “Pacto Europeo para la Salud Mental y el Bienestar”, en Conferencia de alto nivel de la UE “Juntos por la salud mental y el bienestar”, Bruselas, 12-13 junio. Disponible en: Disponible en: ec.europa.eu/health/mental_health/docs/mhpact_es.pdf [14 julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

OMS (2013), Plan de Acción sobre Salud Mental 2013-2020, Ginebra: OMS. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/97488/1/9789243506029_spa.pdf. [14 de julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

ONU (2006), Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad. Disponible en Disponible en www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/documents/tccconvs.pdf [14 de julio de 2015]. [ Links ]

Ortega-Esteban, José (2005), “Pedagogía Social y Pedagogía Escolar: la Educación Social en la Escuela”, en Revista de Educación, núm. 336, España: Ministerio de Educación. [ Links ]

Ortega Esteban, José (1999), “Educación social especializada. Concepto y profesión”, en Educación Social Especializada, Barcelona: Ariel. [ Links ]

Pastor, Juan y Anastasio Ovejero (2009), “Historia de la locura en la época clásica y el movimiento antipsiquiátrico”, en Revista de Historia de la Psicología, vol. 30, núm. 2-3, Valencia: Publicacions Universitat Valencia. [ Links ]

Pérez, Manuel y Luis Navarro (2013), “El Tercer Sector de acción social en España. Situación y retos en un contexto de crisis”, en Revista Tercer Sector, núm. 23. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.fundacionluisvives.org/rets/23/articulos/101406/index.html [16 de febrero de 2014]. [ Links ]

Piat Myra y Judith Sabetti (2010), “Residential Housing for Persons with Serious Mental Illness: The Fifty Year Experience with Foster Homes in Canada”, en Stone, J. H. y M. Blouin [eds.], International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation, Disponible en: Disponible en: http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/236/ [12 de enero de 2013]. [ Links ]

Pleace, Nicholas y Allison Wallace (2011), Demonstrating the Effectiveness of Housing Support Services for People with Mental Health Problems: A Review, Reino Unido: National Mental Health Development Unit. [ Links ]

Pleace, Nicholas y Deborah Quilgars (2013), Improving Health and Social Integration through Housing First: A Review, Reino Unido: Centre for Housing Policy. [ Links ]

Prieto-Rodríguez, Adriana (2002), “Salud Mental: situación y tendencias”, en Revista de Salud Pública, vol. 4, núm. 1, Colombia: Scielo. [ Links ]

Ridgway, Priscilla (2008), “Supported Housing”, en Mueser, Kim T. y Dilip V. Jester [eds.], Clinical handbook of schizophrenia, Nueva York: The Gilford Press. [ Links ]

Ridgway, Priscilla y Anthony Zipple (1990), “The paradigm shift in residential services: from the linear continuum to supported housing approaches”, en Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, vol. 13, núm. 4, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Rodríguez-González, Abelardo [coord.] (2002), Rehabilitación Psicosocial de Personas con Trastornos Mentales Crónicos, Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide. [ Links ]

Rogers, Sally et al. (2009), Systematic Review of Supported Housing Literature, 1993-2008, Boston: Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation. [ Links ]

Román-Brugnoli et al. (2014), “Solidaridad en el debate global y local: reflexión desde un análisis del caso chileno”, enConvergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales , núm. 66, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México . [ Links ]

Rosendal, Niels Jensen (2013), “Social Pedagogy in modern times”, en Education Policy Analysis Archives, vol. 21, núm. 36. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/1217/ [3 de mayo de 2013]. [ Links ]

Ruggeri, Mirella et al. (2000), “Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness”, en British Journal of Psychiatry, núm. 177, Reino Unido: The Royal College of Psychiatrists. [ Links ]

Scheyett et al. (2013), “Recovery in severe mental illnesses: a literature review of recovery measures”, en Social Work Research, vol. 37, núm. 3, Washington: National Association of Social Workers. [ Links ]

Segal, Steven P. y Pamela L. Kotler (1993), “Sheltered care residence: ten-year personal outcomes”, en American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, vol. 63, núm. 1, USA: Wiley . [ Links ]

Siegel, Carol E. et al. (2006), “Tenant outcomes in supported housing and community residences in New York City”, enPsychiatric Services , vol. 57, núm. 7, USA: American Psychological Association . [ Links ]

Stanhope, Victoria y Kerry Dunn (2011), “The curious case of Housing First: The limits of evidence based policy”, en International Journal of Law Psychiatry, vol. 34, núm. 4, Ámsterdam: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Tsemberis, Sam (2010), “Housing First: ending homelessness, promoting recovery and reducing costs”, en Ellen, Ingrid Gould y Brian O´Flaherty [eds.], How to House the Homeless, Nueva York: Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Tsemberis, Sam y Ronda Eisenberg (2000), “Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals”, enPsychiatric Services , vol. 51, núm. 4, USA. [ Links ]

Úcar, Xavier (2013), “Exploring different perspectives of Social Pedagogy: towards a complex and integrated approach”, enEducation Policy Analysis Archives , vol. 21, núm. 36. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/1282 [3 de mayo de 2013]. [ Links ]

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo (2011), “Antipsiquiatría. Deconstrucción del concepto de enfermedad mental y crítica de la razón psiquiátrica”, en Nómadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas, vol. 31, núm. 3, Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid [ Links ]

Whitley, Rob y Rosalyn Denise Campbell (2014), “Stigma, agency and recovery amongst people with severe mental illness”, en Social Sciences & Medicine, núm. 107, Ámsterdam: Elsevier . [ Links ]

Wong, Yin-Ling et al. (2011), “Social Integration of People with Serious Mental Illness: Network Transactions and Satisfaction”, en Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, vol. 38, núm. 1, USA: Springer [ Links ]

1All tables are at Annex, at the end of the present article (Editors’ note).

2This makes practitioners and public managers doubt the potential of residential programs for people with SMD and how these can positively produce important results for health, more so at times when political and administrative decisions regarding the funding and setting into motion of programs depends and is based upon the much-sought-after scientific evidence, supported on positivism and on the generalization of results by means of statistical results (Stanhope and Dunn, 2011). This way, reviews such as a Chilvers’ et al. (2010) do no find evidence at all, since they base their study solely on researches with experimental methodology with random trials. However, other reviews, Rogers et al. (2009) or Nelson (2010), put forward the existence of important and significant literature that might be useful for those interested, both patients and workers and those responsible for the programs, as well as for other aspects of mental health and socio-educational intervention.

Annex

Source: López Álvarez et al. (2004: 108).

Table 3: Differences between the “residential continuum” and supported housing models

Received: June 16, 2015; Accepted: May 27, 2016

texto em

texto em