Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Madera y bosques

On-line version ISSN 2448-7597Print version ISSN 1405-0471

Madera bosques vol.14 n.1 Xalapa Mar. 2008

Artículo de investigación

Planning forest recreation in natural protected areas of southern Durango, Mexico

Planeación de la recreación forestal en áreas naturales protegidas del sur de Durango, México

Gustavo Pérez Verdín1, Martha E. Lee2 y Deborah J. Chavez3

1 Postdoc Research Associate. Mississippi State University. Box 9681. Mississippi State, MS 39759. [Correspondence author] gperez@cfr.msstate.edu.

2 School of Forestry. Northern Arizona University. P.O. Box 15018. Flagstaff, AZ, 86011-5018. Martha.Lee@nau.edu

3 Pacific Southwest Research Station. USDA Forest Service. 4955 Canyon Crest Drive. Riverside, CA, 92507. dchavez@fs.fed.us

ABSTRACT

This research investigated the usefulness of the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) for managing forest recreation in two natural protected areas of southern Durango, Mexico. We used on-site interviews to document the recreation activities visitors participated in, the characteristics of their preferred recreation sites, and socio-demographic information. A cluster analysis identified visitor groups based on the characteristics of preferred recreation sites and the resulting clusters were compared to the recreation activities and socio-demographic data to create a typology of visitors. We used the ROS framework to identify three classes in each natural protected area including (1) zones with easy access and basic facilities (ROS rural class), (2) natural-appearing zones with few facilities (ROS roaded class), and (3) reserve zones (ROS semiprimitive non-motorized or primitive class). Overall, the ROS framework appears to fit appropriately in these two case studies and could be used for recreation planning purposes in other forest areas of the country.

Key words: Forest recreation, Recreation Opportunity Spectrum, Michilía Biosphere Reserve, El Tecuán Recreational Park, planning frameworks, recreation resources inventory.

RESUMEN

Se investigó la utilidad del Espectro de Oportunidades de Recreación (EOR) para la planeación de la recreación forestal en dos áreas naturales protegidas del sur de Durango. Se usaron entrevistas de campo para documentar las actividades recreativas realizadas por los visitantes, las características de los sitios recreativos que ellos seleccionaron e información socio-demográfica. La técnica de análisis grupales clasificó los visitantes de acuerdo a las características de los sitios seleccionados y los grupos resultantes se compararon con las actividades recreativas realizadas y la información socio-demográfica obtenida. Con apoyo del EOR, se identificaron tres clases de recreación en cada área natural protegida, las cuales fueron: (1) Zonas con fácil acceso y servicios básicos (consistente con la clase rural del EOR); (2) Zonas de apariencia natural con pocos servicios (clase de caminos del EOR) y (3) Zonas de reserva (clases semiprimitiva no motorizada o primitiva). De manera general, el sistema EOR se adecuó bien a las condiciones de los dos casos de estudio y podría usarse para actividades de planeación de la recreación forestal en otros lugares del país.

Palabras clave: Recreación forestal, Espectro de Oportunidades de Recreación, Reserva de la Biosfera La Michilía, Parque Recreativo el Tecuan, esquemas de planeación, inventario de recursos recreativos.

INTRODUCTION

The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) is a framework commonly used in the United States (US) for planning and managing recreation use in natural settings (usda, 1982). The us Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management use the ROS concept to manage recreation opportunities primarily in wildland settings where the physical environments provide a continuum or spectrum of recreation opportunities. This spectrum is generally achieved by combining and mapping different levels of physical and social characteristics of the environment including activities, settings, and experiences (Driver et al., 1987). The social psychological foundation of the ROS is the expectancy-valence theory (Moore, 1999). Expectancy or cognitive theories have their roots in the principle of hedonism which suggests that individuals tend to seek pleasure and avoid pain (Steers and Porter, 1987). Expectancy, in this context, means the belief of probable outcomes from given actions. Valence, introduced by Lewin (1938), means the attractiveness of an outcome to an individual (Moore, 1999). Within expectancy-valence theory, an outcome's attractiveness (valence), combined with the rational expectation that a particular outcome will or will not be realized (expectancy), motivates an individual to participate or not to participate in a given activity (e. g., camping), within a given setting (e.g. big trees around) (Driver et al., 1987; Moore, 1999).

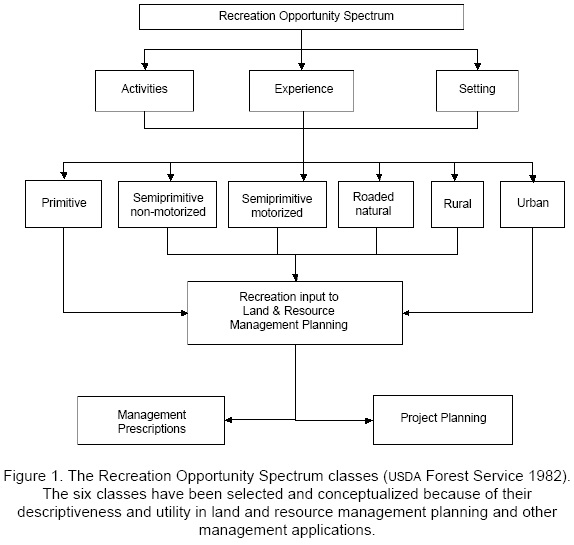

This foundation drives the hypothesized causal linkages among activities, settings, and experiences in the r o s framework. Recreation activities are defined as behaviors such as hiking and camping; recreation settings are the places where activities take place and include all physical resources (e.g., topography, density of forests, water), social (e.g., number and type of others), and managerial (e.g., permits, fee systems, facilities); and recreation experiences are defined as a package of psychological outcomes realized from a recreation engagement (Manfredo et al., 1983). Various combinations of these three key components delineate six recreation opportunity classes: primitive, semi-primitive non-motorized, semi-primitive motorized, roaded natural, rural, and urban (Douglass, 1993) (Figure 1). Criteria such as remoteness of the area, size, and evidence of humans are used to classify lands suitable for opportunities in difference classes along the spectrum. By applying these criteria and associate standards to a piece of land, it is possible to delineate the recreation opportunities available to recreationists. For example, an area that is isolated from the sights and sounds of human activities provides opportunities for solitude and introspection. Adeveloped campground offers opportunities for socializing and learning.

The ROS framework was designed to be adapted to different physical and cultural conditions and is being applied both in the us and abroad. ROS abroad applications include New Zealand (Kliskey 1998; Sutton 2004), Australia (Parkin et al., 2000), and Japan (Yamaki et al., 2003). In Mexico, however, only a few studies have documented the application of recreation planning frameworks for managing outdoor recreation. The topography and the unique land tenure system affect the patchiness of ecosystems, and managerial settings could require somewhat different criteria and standards than the original ROS recreation opportunity classes. Gonzalez-Guillen et al., (1996) studied 14 natural parks of the central state of Mexico to identify forest areas with potential for recreational purposes. They identified 27 forest areas based on the physiographic aspects, hydrology, vegetation types, wildlife, and facilities in the area. Though they never mentioned the concept of the ROS, they used the setting component as the primary source of classification.

Other planning frameworks exist for managing recreation in natural protected areas as well. Farrell and Marion (2002) discussed the possibility of using a modification of the visitor impact management approach as an alternative to other planning frameworks in Costa Rica, Chile, and Mexico. Although they do not present results of the application of this framework, they suggest that it can be useful not only for evaluating visitor impact on natural resources, but also for managing economic and socio-cultural impacts related to visitation and addressing other specific protected area management issues.

One of the big differences of ROS over other planning frameworks is the easy incorporation of visitor's behaviors into maps or Geographical Information Systems. In this study, we used preference settings to map the recreation opportunities by virtue of the fact that settings are the ROS component most readily influenced by resource managers (Driver et al., 1987).

OBJECTIVE

The general goal of this study is to provide insights into managing recreation and to describe the potential use of the ROS framework in Durango forest areas. Resource managers can use the ROS framework as a tool to inventory, classify, and manage recreation opportunities based upon recreation setting preferences. Thus, the study's objectives are to: (1) identify visitors' preferences for recreation setting characteristics; (2) describe visitor types in terms of recreation activities, reasons for visiting, and other demographic information, and (3) Identify potential recreation opportunity classes based on visitors characteristics and preferences.

STUDY AREAS

The natural protected areas chosen for this study are the 30,000-hectare Michilía Biosphere Reserve (MBR) that was established in 1979 as part of the Man and Biosphere International program, and a 778-hectare, state-owned El Tecuán recreational park (TEC). Even though t e c has not been officially declared as a natural protected area, its management objectives match with those of the National Parks category i.e., natural resources conservation, outdoor recreation, and aesthetics. The study areas are located in the southeast and southcentral areas of the state of Durango, Mexico, respectively (Figure 2).

The MBR has a few facilities to provide outdoor recreation opportunities. These include grills along the main road and around attraction sites as well as interpretative and directional signs to reach ecotouristic points such as the wolf and white-tail deer breeding centers or the research station located near the center of the area (Figure 3). Because no physical boundaries were observed on the field, we used the geographical information provided in the presidential decree to delimit the area.

In contrast, TEC has more facilities for outdoor recreation, such as picnic areas, basketball courts, restrooms, cabins, and a few dispersed recreation facilities, and it is easily located both on the field and maps. Even though users are required to pay an entrance fee (approximately $10 U.S. dls. per person), the management of the park is unable to maintain clean and safe facilities due to a lack of resources. During the peak months, TEC experiences moderate vegetation and soil impacts, especially in the picnic and camping areas. Visitors frequently scrape trees and cut branches to build campfires (Figure 4), or hike in recently reforested areas causing impacts to newly planted trees. We estimated that El Tecuán Recreational Park (TEC) receives more than 3,000 visitors while MBR receives approximately 1,000 visitors per year.

Local ranchers use both MBR and TEC for grazing activities and divide the areas into small fenced plots. The fences serve as physical barriers that limit the movement of motorized vehicles into deeper parts of the areas. In turn, this lack of movement produces a relatively high demand/use of some recreation sites and increases the risk of ecological impacts. The recreation and grazing-related impacts suggest a need for managing and planning outdoor recreation opportunities in these areas. More details on the characteristics of the study areas and survey methods can be found in Perez Verdin (2003).

Data Collection and Analysis

Data for this study consisted on visit o r's interviews, maps, aerial photos, field trips, and draft management plans. Due to a low number of visitors in both areas we did not follow statistic methods to draw a sample. We interviewed every single visitor or group of visitors in the m br (n=73) and asked all te c visitors or group of visitors to voluntarily fill out a questionnaire and leave the completed questionnaire with park staff as they left the area (there is only one entrance/exit to the area, n=100). T h e information was gathered in the summer of 2002. We had no refusals among m br vistors, but 23 t e c visitors refused to answer the questionnaires. Information gathered with the questionnaires consisted of documenting (1) the recreation activities that visitors participated in, (2) characteristics of preferred recreation settings, and (3) reasons for visiting the area and socio-demographic variables. Setting attribute preferences were measured using a seven-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Maps, aerial photos, and other park-related information were provided by the m br and TEC staffs as well as by the Department of Natural Resources of the Government of Durango.

A cluster analysis diffe re nti ate d among preferred attributes of the recreation settings. The setting attributes included easy access to the area, many interpretative signs for guiding visitors within the area, many interpretative signs for using the forest, distance from main roads, few social encounters, high degree of naturalness, many big trees in and around the site, no forest harvesting activities, no grazing and agricultural activities, and basic facilities, e.g., grills, tables, and restrooms. The purpose of cluster analysis was to determine if visitors preferred distinct classes or zones of recreation settings in each area. We identified the clusters using the average within-groups linkage method, measured by the Euclidian distance (Romesburg, 1990).

The recreation setting preference clusters were further compared and described based on the recreation activities visitors participated in, socio-demo-graphic characteristics, and reasons for visiting the area. For the latter, we identified nine motivation domains (Manning 1999) including: (1) participating in recreation activities; (2) learning; (3) family/friends together; (4) escape pressure; (5) enjoy nature; (6) physical rest; (7) risk reduction; (8) nostalgia; (9) other. We also used the characteristics of the selected recreation settings to identify potential recreational zones in the two areas. We constructed a ROS-like map to represent the diversity among setting opportunities for each area based on visitors' setting preferences.

Cross-tabulation procedures were used to examine the levels of association between clusters and descriptor variables such as recreation activities, motivation domains of reasons, and sociodemographic data. The chi-square statistics tested the significance of the levels of association among the setting clusters and descriptor variables.

RESULTS

We found significant differences between the two visitor samples in terms of education, household income, employment and distance of travel to the two areas. MBR visitors had lower levels of education, income, and employment than TEC visitors. In both areas, visitors tended to participate in large groups: MBR groups averaged 8.2 members while TEC groups averaged 10.7 members. Group sizes ranged from two persons to a maximum of 40 people in the TEC and 20 people in the MBR area. Due to this group participation of visitors our sample was made up of 73 individuals in TEC and 100 individuals in the MBR.

El Tecuán (TEC) Visitors

Cluster analysis of preferred setting attributes identified two types of TEC visitors. Thirty-six individuals (36% of the sample) were classified in cluster 1 and 63 individuals (63 % of the sample) were classified in cluster 2. We found significant differences between the clusters in their preferences for a high degree of naturalness, many big trees in and around the site, no harvesting activities, and no grazing/agriculture activities. Respondents in cluster 2 were more intolerant of setting modifications including harvesting and grazing/agricultural activities. They preferred undisturbed sites with many big trees in and around the sites (Table 1).

Results showed that both clusters are socio-demographically similar and had no significant differences in the reasons that motivated their visit to TEC. Cluster 2 visitors were more likely to participate in nature-oriented activities and preferred recreation settings with non-noticeable setting alterations (Table 2).

MBR Visitors

Cluster analysis of setting preferences also identified two types of visitors. Thirty-one individuals (43% of the sample) were classified in cluster-1 and 41 individuals (56 % of the sample) were classified in cluster 2. We found significant differences between the two groups in their preferences for easy access to the site, many interpretative signs for guiding within the area, few social encounters, and many big trees in and around the site (Table 1). Both MBR clusters are socio-demographically similar and had no significant differences in the reasons that motivated their visit to MBR. They basically come to the reserve to enjoy nature, hike, picnic, and watch wildlife. We did not find any significant association between the clusters in terms of participation in any of the recreation activities, motivations, or setting clusters (Table 3). Cluster-2 visitors were more likely to camp, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Zoning Outdoor Recreational Opportunities

We used the information from the cluster analysis to map potential recreation opportunity classes in TEC and MBR. Because our results indicated no significant differences in the recreation activities, reasons for visiting, and socio-demo-graphic characteristics of cluster groups, the recreation opportunity maps were based primarily on the significant differences found in the recreation setting preferences of visitors to the two areas (Table 1). Based on the draft document "Resource Management Plan for El Tecuán Area" developed by the government of the state of Durango, which describes the location of roads, hiking trails, forest vegetation types (dgo-semarnat 2002), along with topographic maps and orthophotos, we identified the recreation opportunity zones in TEC. We considered other topographic/physical information to identify places with high degree of naturalness, no harvesting activities, and no evidence of agriculture/ cattle activities.

Figure 5 presents a zoning of the TEC area that attempts to meet current and future needs for recreation opportunities and minimize recreation impacts. We identified zone A for cluster 1 visitors, zone B for cluster 2 visitors, and the rest of the area would be held in reserve. This distribution should reduce the impact on zone A by accommodating visitors in a larger area. In this scenario, the area for the cluster 1 visitors is 247 ha (32% of the TEC area) and the area for the cluster 2 visitors is 264 ha (34% of the area). In addition, zone C is proposed to be kept in reserve, which in turn may serve to receive future visitors that may feel displaced by a potential increase in demand for undisturbed areas. This zone represents 34 percent (267 ha) of the total area and includes the most remote sites with no access by motorized vehicles.

The map in figure 5 should also meet the common preferences of both groups, who indicated relatively similar preferences for recreation site characteristics. For example, while the cluster 1 visitors did not rate a high degree of naturalness as important as for the cluster 2 visitors, the former is nonetheless concerned with naturalness, big trees in and around, and no grazing or harvesting activities when seeking the recreation sites. Both groups also demand natural-appearing settings and basic facilities.

We classified the recreation zones for the MBR following the same procedure as for the TEC area. We used large-scale topographic maps to locate roads, major attractions, and the rudimentary facilities to provide outdoor recreational opportunities. We also used data from the natural resources management plan developed by the MBR staff (rblm 2001) including elevation lines, vegetation types, and hydrologic aspects to help delineate the recreation opportunity zones. Based on the differences of the preferred characteristics between the two recreation settings groups, we identified opportunity zones for both types of visitors. For example, one of the characteristics of the cluster 2 visitors was more tolerant of social encounters than cluster-1 visitors. Cluster 2 visitors were also more likely to participate in picnicking and hiking activities.

Figure 6 presents the recreation opportunity zones for the MBR. Because of the easy access, zone A is more likely to receive more visitors than the rest of the MBR. Cluster 2 visitors will more likely visit zone A because it has easier access, there is little concern about social encounters, and it has more basic facilities (grills, tables). The 8007-ha zone A represents 23 percent of the total area, it is located in the center of MBR and close to the main roads.

Cluster 1 visitors would likely prefer zone B, which comprises 19,264 ha (55 percent of the total area). Unlike the cluster-2 visitors, it was more important for cluster 1 visitors to have few social encounters and preferred a high degree of accessibility to the recreation site. Cluster 1 visitors needed many interpretative signs to guide them within the area and they were more likely to participate in camping, collecting products and plants, and developing research/educational activities than cluster 2 visitors.

Since the number of visitors to each zone is relatively small, MBR appears to offer sufficient area to meet current and future needs for recreation opportunities. We included zone C, a remote area that comprises 23 percent of the total M B R (7,803 ha), to protect the reserve core from potential recreation impacts. The reserve core is located in the northwest part of the MBR, around the Cerro Blanco Peak, and could also fulfill potential demand for more primitive areas in the future.

To summarize, the resulting maps identified three zones to classify lands for recreational opportunities in TEC and MBR: (A) zones with easy access and basic facilities, (B) natural-appearing zones having less access and fewer facilities, and (C) reserve zones. Using the ROS criteria, these zones could be classified as (1) rural; (2) roaded natural; and (3) semi-primitive non-motorized or primitive areas, respectively. This analogy is based on key common components that matched the ROS criteria: degree of naturalness, level of access, facilities, interpretative signs, and social settings. The degree of naturalness, expressed as remoteness and evidence of humans in the ROS, along with level of access and facilities correspond to the biophysical setting as described in the ROS criteria, and interpretative signs are included within the managerial setting.

DISCUSSION

In addition to their socioeconomic profile, a key distinction between MBR and TEC visitors when selecting the recreation sites is the evidence of cattle grazing or agricultural activities in the area. Managers allow the use of both natural areas for grazing activities with more evidence in the MBR. As noted earlier, during the research we found a considerable number of fences that not only restrict the use of natural resources for recreation use, but also for game movement and displacement to other areas. Results suggest that MBR visitors were less concerned than TEC visitors to cattle grazing or agricultural activities when selecting a recreation site. on the variable no grazing/agricultural activities, MBR visitors had a mean of 0.93 whereas TEC visitors reported a mean of 1.68. The results indicated that TEC visitors, especially cluster-2 visitors, avoided recreation sites if evidence of cattle grazing was found in or around the site. In this sense, resource managers should consider the removal of cattle and fences, especially in zones B and C of the TEC area. Another distinction between TEC and MBR is related to the number of visitors each one receives. We estimated an annual visitation during the peak months (i.e., March-September) of 2000 persons to the TEC area and up to 800 people to the m br for recreational purposes. However, the MBR (including the core and buffer zone) is 40 times larger than the TEC area.

The classification presented in this study follows the original ROS criteria and standards as identified in the US Forest Service guidelines. However, the ROS has been adapted to local conditions using visitors' interviews, field trips, and cartographic information. The resulting maps can help resource managers to estimate demand (in terms of number of visitors to a particular area) and supply of outdoor recreational opportunities (available area for those visitors) based on the identification of the preferred recreation setting characteristics. Recognizing that the management of each recreation area is different and site specific, the purpose of this research is to contribute to the study of supplydemand analysis of recreation opportunities in recreational areas in Mexico.

In this context, other planning frameworks -or combinations of them- can be used for the same or different purposes. While ROS provides a system for identifying and providing a range of recreation opportunities for visitors with different needs, it does not deal specifically with the management of recreation impacts. The application of other planning frameworks, such as limits of acceptable change and visitor impact management, would complement ROS planning (Farrell and Marion 2002). In addition, since recreation is a component of ecosystem management, ROS can be combined with other multiresource planning frameworks.

Overall, the ROS framework appears to fit appropriately in these two case studies. In the United states, and other countries where the framework is being applied, the ROS is used primarily for managing and planning recreational opportunities in the wildlands. These areas, like the MBR and TEC, belong to the government and the agencies responsible for managing natural resources utilize the ROS as the primary approach to provide quality recreational opportunities. In Mexico, despite the increasing interest in recreation, few forestlands are destined for recreational opportunities. one alternative is to involve other non-federally owned properties to increase the lands' value for recreational purposes, such as the ejidos and comunidades' forestlands. Ejidos' forestlands can fulfill the lack of available recreation areas and at the same time, reduce the pressure on timber production. When we asked visitors their opinions about the possible participation of ejidos and private owners in providing recreational opportunities, close to 86 percent of the entire sample responded positively. Moreover, 80 percent were willing to pay a fee to those ejidos/comunidades to increase the usability of area for recreational purposes.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of this study was to identify and describe visitors' preferences for recreation setting characteristics in terms of recreation activities, reasons for visiting, and select socio-demographic characteristics such as income, education, age, and occupation. With this information, we classified potential recreation opportunity zones in the MBR and TEC. Cluster analysis identified two types of visitors indicating a marginal demand for diversity in recreation settings. One of them was more likely to visit recreation sites with easy access and interpretative signs, and the other was more likely to visit recreation sites with somewhat more complicated access and low presence of visitors. We compared the activities, motivations (experiences), and recreation settings -the key components of the ROS concept- but we did not find any significant association between the two types of visitors in each area. We attributed the lack of association among settings, activities, and motivations to various survey limitations including questionnaire design and interpretation, and size and homogeneity of the sample. For example, we believe that the lack of association between the recreation setting groups and socio-demographic variables was because our sample of visitors consisted of a very socio-demographically homogenous group that participated in similar recreation opportunities and had similar motivations to visit the recreational area. Likewise, no significant differences were also found between motivations and recreation activities. Further research that addresses these potential associations is necessary to assess the linkages among the components of the behavior recreation model.

This study also showed that the estimation of demand and supply of outdoor recreational opportunities can be based on the identification of the preferred recreation setting characteristics. The findings can serve as examples of standards and setting characteristics for planning and management of outdoor recreational areas.

Resource managers (and ejidos/ comunidades) should also follow adaptive management procedures in implementing any new management actions in MBR and TEC by outlining steps for monitoring the consequences of management actions. The treatment of these management practices as experiments is critical because it provides an opportunity to test unproven concepts believed to be correct, and it provides focus for monitoring the outcomes of these activities. Resource managers might coordinate data collection and data management methods for the two areas to ensure that data sets can be integrated for further analysis. By implementing, monitoring, and evaluating this classification system to manage recreational opportunities, resource managers are able to gain valuable information about the acceptability, effectiveness, and cost of managing recreation opportunities (Chavez, 2002). The classification of lands to provide recreation opportunities involves the analysis of causal relationships between management actions and visitor satisfaction (Rollins et al., 1998). The recreation opportunity classification can be adapted to respond to progressive management actions. We recommend more research to study the ejidos' participation in providing recreation opportunities and the linkages among the three components of ROS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the Pacific Southwest Research Station (USDA Forest Service) and Northern Arizo n a University under the agreement PSW-02-JV-11272137-010. The authors wish to express their gratitude to the people that participated in the interviews as well as to the staffs of the Forest Department of the state of Durango and the Michilía Biosphere Reserve. Two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged for their contribution in an early manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

Chavez, D.J. 2002. Adaptive management in outdoor recreation: Serving Hispanics in southern California. Western Journal of Applied Forestry 17 (3):129-133 [ Links ]

DGO-SEMARNAT. 2002. Plan de manejo integral forestal para el parque recreativo El Tecuan, municipio de Durango, Dgo. 93 p. [ Links ]

Douglass, R.W. 1993. Forest Recreation. Waveland Press. Prospect Heights, IL. 373 p. [ Links ]

Driver, B.L., P.J. Brown, G.H. Stankey and T.L. Gregoire, 1987. The ROS Planning System: Evolution, basic concepts, and research needed. Leisure Sciences 9:201-212. [ Links ]

Farrell, T.A. and J.L. Marion. 2002. The protected area visitor impact management (pavim) framework: A simplified process for making management decisions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 10(1): 31-51. [ Links ]

González-Guillen, M., R. Valdez-Lazalde, and C. Velasco-Gonzalez, 1996. Definición de áreas forestales con potencialidad recreativa. Agrociencia 30:129-138. [ Links ]

Kliskey, A.D. 1998. Linking the wilderness perception mapping concept to the recreation opportunity spectrum. Environmental Management 22(1): 79-88. [ Links ]

Lewin, K. 1938. The conceptual representation and the measurement of psychological forces. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Mader, R. 1998. Mexico: Adventures in Nature. John Muir Publications. Santa Fe, NM. 321 p. [ Links ]

Manfredo, M., B. Driver and P. Brown. 1983. A test of concepts inherent in experience-based setting management for outdoor recreation areas. Journal of Leisure research 15: 263-283. [ Links ]

Manning, R.E. 1999. Studies in outdoor recreation: Search and research for satisfaction. Oregon State University Press. Corvallis, OR. 374 p. [ Links ]

Moore, M.D. 1999. Recreation specialization as an alternative to sustained yield management and the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum. Unpublished Ph D Dissertation. Northern Arizona University. [ Links ]

Parkin, D., D. Batt, B. Waring, E. Smith and H. Phillips. 2000. Providing for a diverse range of outdoor recreation opportunities: "a micro-ROS" approach to planning and management. Australian Parks and Leisure 2(3): 41-47. [ Links ]

Perez-Verdin, G. 2003. Evaluating Strategies for Managing Outdoor Recreation Opportunities in Southern Durango, Mexico. Master Thesis. Northern Arizona University. 140 p. [ Links ]

RBLM. 2001. (Dirección de la Reserva de la Biosfera La Michilía). Plan de manejo integral de los recursos naturales en la Reserva de la Biosfera La Michilía. Borrador. Documento no publicado. 77 p. [ Links ]

Rollins, R., W. Trotter and B. Taylor. 1998. Adaptive management of recreation sites in the wildland-urban interface. Journal of Applied Recreation Research 23 (2): 107-125. [ Links ]

Romesburg, C.H. 1990. Cluster Analysis for researchers. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Steers, R.M. and L.W. Porter. 1987. Motivation and work behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Sutton, S. 2004. Outdoor recreation planning frameworks: An overview of best practices and comparison with Department of Conservation (New Zealand) planning processes. In: Smith, K.A., Schott, C. (Eds). Proceedings of the New Zealand tourism and hospitality research conference. Wellington. pp. 407-423. [ Links ]

USDA Forest Service. 1982. ROS users guide. Washington, D.C. 124 p. [ Links ]

Yamaki, K., O. Hirota, Y. Shoji, T. Tsychiya and K.Yamaguchi. 2003. A method for classifying recreation area in an alpine natural park using Recreation Opportunity Spectrum. Journal of Japanese Forest Society 85 (1): 55-62. [ Links ]