Introduction

The family Sapotaceae Juss. comprises tropical trees and shrubs, including species of interest (Popenoe, 1934). In Mexico, this family is represented by five genera and 38 species (Newman, 2008). Among the species of this family the mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) stands out because of the economic importance of its fruits, which are mainly consumed fresh and are appreciated for their sensorial characteristics (Pennington & Sarukhán-Kermez, 2005). Apparently, this species is native to south-southeast Mexico and low-lying areas of Central America. It is currently cultivated in several tropical areas: The United States (specifically in Florida), Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia and the Caribbean islands; in addition, there is interest in cultivating it in Australia, Israel, the Philippines, Vietnam, Spain and Venezuela (Balerdi & Crane, 2015).

In Mexico, for 2014, 1,651 hectares planted with this species in 15 states of the country and a total production of 17,586 t of fruit were reported. Yucatán, Guerrero, Chiapas and Michoacán stand out for their harvested area and production (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera [SIAP], 2015).

Alia-Tejacal et al. (2007) report the nutritional benefits of this species, emphasizing its high content of vitamins (especially vitamin A and C), essential amino acids and minerals (highlighting Ca and K). It also contains carotenoids (3.7 mg∙100 g-1 fresh weight of beta carotene) and phenols (646 mg∙kg-1 fresh weight), the latter of which, due to their antioxidant capacity, could be associated with the prevention of some chronic diseases (Alia-Tejacal, Soto-Hernández, Colinas-León, & Martínez-Damián, 2005; Alia-Tejacal et al., 2007).

In Mexico, mamey sapote, which is cross-pollinated, is propagated by seed, generating broad genetic variability, which makes its commercialization difficult because there is no homogeneity in fruit production or quality (Villarreal-Fuentes, Alia-Tejacal, Hernández, Pelayo-Zaldivar, & Franco-Mora, 2015). In addition, its cultivation in the country has not improved and its planted area has not expanded; moreover, its productive potential, in particular the availability of the gene pool associated with its productivity, is unknown (Villegas-Monter & Granados-Friely, 2012).

In order to make a plan about the collection and safeguarding of mamey sapote germplasm, as well as its evaluation, it is important to know its distribution and the different climatic regimes where it grows and to identify the potential cultivation zones and the possible variation in them due to climate change (Zagaja, 1988). All this can be obtained by using several Geographic Information System (GIS) methods (Guarino, Jarvis, Hijmans, & Maxted, 2002; Hijmans, Guarino, & Mathur, 2012; Jones, Guarino, & Jarvis, 2002; Núñez-Colín & Goytia-Jiménez, 2009; Scheldeman & van Zonneveld, 2011).

In the case of mamey sapote there are no specialized studies on the subject and information on its distribution is dispersed; therefore, the aim of this research was to generate maps of the natural geographic and eco-climatic distribution of mamey zapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) growing areas in Mexico and model potential areas according to the climate change estimated for 2050, by using GIS.

Materials and methods

Information sources for the desk analyses were: passport data of the projects registered in the SNIB-CONABIO database (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, 2015; Table 1), Tropicos.org (Missouri Botanical Garden, 2015; 63 passport data) and optimal mamey sapote climatic data recorded in the FAO database (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2007).

Table 1 Project and source of the passport data of Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore & Steam from the SNIB-CONABIO database, Mexico, used in the GIS analysis.

| Project | Source | Project citation | Number of data used |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA002 | AA002 E008 K004 P026 | Lorea-Hernández, F., Peredo, M., & Durán, C. (2014). Actualización de las bases de datos del Herbario XAL. Fase III. (Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto AA002). Ciudad de México: Instituto de Ecología, A. C. | 34 |

| AA007 | AA007 L282 | Contreras-Jiménez, J. L. (2005). Actualización e incremento de la base de datos del Herbario de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyectos No. AA007 y L282). Ciudad de México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla DIHMO. | 4 |

| AC002 | AC002 | Zamora-Crescencio, P., Sánchez-González, M. C., & Aragón-Axomulco, L. (2005). Formación del banco de datos del herbario (UCAM). (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. AC002). Ciudad de México: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Centro de Investigaciones Históricas y Sociales. | 2 |

| AE013 | Q047 | Panero, J. L., & Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). (2003). Catálogo electrónico de especímenes depositados en el Herbario de la Universidad de Texas en Austin, Fase IV. (Bases de datos ejemplares mexicanos, SNIB-CONABIO proyectos No. AE013, V057, V007 y Q047). Ciudad de México: The University of Texas. | 1 |

| AE019 | AE019 | Toledo-Manzur, V. M. (2005). Potencial económico de la flora útil de los cafetales de la Sierra Norte de Puebla. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. AE019). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| B002 | B002 | Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G., & Meave-de Castillo, J. A. (1998). Inventario de la biodiversidad de vertebrados terrestres de los Chimalapas, Oaxaca. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO. No. B002). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 167 |

| BC002 | T031 | Cuevas-Sánchez, J. A. (2006). Computarización de la base de datos del Banco Nacional de Germoplasma Vegetal - Fase 2. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyectos No. BC002 y T031). Ciudad de México: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. | 7 |

| BC007 | BC007 | Fernández-Nava, R., Reyes-Toledo, B., & Casales-Gómez, M. (2007). Computarización del Herbario ENCB, IPN. Fase IV. Base de datos de la familia Pinaceae y de distintas familias de la clase Magnoliopsida depositadas en el Herbario de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas-IPN. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyectos No. BC007). Ciudad de México: Instituto Politécnico Nacional. | 11 |

| DC013 | DC013 | Vázquez-Torres, M., & Bojórquez, L. H. (2011). Base de datos computarizada del herbario CIB, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Veracruzana. (Informe final SNIB-CONABIO, proyecto No. DC013). Ciudad de México: Universidad Veracruzana. | 2 |

| EC018 | EC018 | Valdez-Hernández, M. (2013). Base de datos del Herbario CIQR de El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, unidad Chetumal. (Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. EC018). Ciudad de México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. | 2 |

| gbif | 12084 | Missouri Botanical Garden. Global Biodiversity Information Facility. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.gbif.org/dataset | 10 |

| gbif | 14036 | Global Biodiversity Information Facility. (2012). University of British Columbia Herbarium - Vascular Plant Collection. Retrieved from http://www.gbif.org/dataset | 1 |

| HA005 | EC009 HA005 | Pérez-Farrera, M. A., Martínez-Camilo, R., Martínez-Meléndez, N., & Martínez-Meléndez, M. (2011). Integración de bases de datos, actualización y sistematización de la colección de flora del Herbario Eizi Matuda (HEM). (Informe final SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. HA005). Ciudad de México: Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. | 2 |

| HA016 | BA006 | Hernández-Aguilar, S. (2014). Depuración de la colección y base de datos del Herbario CICY. Fase IV. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyectos Nos. HA016, DC002, BA006, U009, K037, B070 y P143). Ciudad de México: Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A. C. | 8 |

| INFyS2010 | INFyS. 2010 | Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). (2011). Base de datos del Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos 2004 - 2009. Ciudad de México: Author. | 22 |

| J001 | J001 | Martínez-Hernández, E. (1999). Propuesta para sistematizar la colección palinológica de polen reciente y fósil del IGLUNAM. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. J001). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| J002 | J002 | Bravo-Marentes, C. (1999). Inventario nacional de especies vegetales y animales de uso artesanal. (Hoja de cálculo SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. J002). Ciudad de México: Asociación Mexicana de Arte y Cultura Popular, A. C. | 1 |

| J063 | J063 | Reygadas-Prado, D. D. (1999). Sistema de apoyo a la toma de decisiones para la reforestación rural en México. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. J063). Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación e Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias. | 1 |

| J084 | J084 | Batis-Muñoz, A. I., Alcocer-Silva, M. I., Gual-Díaz, M., Sánchez-Dirzo, C., & Vázquez-Yanes, C. (1999). Árboles mexicanos potencialmente valiosos para la restauración ecológica y la reforestación. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. J084.). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 9 |

| L255 | L255 | Rendón-Aguilar, B., & Núñez-Farfán, J. (1999). Flora útil del municipio de la Huerta, Jalisco. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. L255). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| M002 | M002 | Levy-Tacher, S. I. (1999). Contribución al conocimiento de la flora útil de la selva Lacandona. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. M002). Ciudad de México: Conservation International México, A. C. | 1 |

| M099 | M099 | Meave-del Castillo, J. A., & Luis-Martínez, A. M. (2000). Caracterización biológica del Monumento Natural Yaxchilán como un elemento fundamental para el diseño de su plan rector de manejo. (Hoja de cálculo SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. M099). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| Mobot | Mobot | Jardín Botánico de Missouri. (2005). Base de datos del herbario del Jardín Botánico de Missouri. Missouri: Jardín Botánico de Missouri. | 29 |

| P140 | P140 | Gutiérrez-Garduño, M. V. (1999). Sistematización del Herbario Nacional Forestal Biól. Luciano Vela Gálvez. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. P140.). Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Rural e Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias. | 1 |

| Q017 | Q017 | Rzedowski, J., & Zamudio, S. (2001). Etapa final de la captura y catalogación del Herbario del Instituto de Ecología, A. C., Centro Regional del Bajío. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyectos No. Q017, J097 y F014). Ciudad de México: Instituto de Ecología, A. C. | 1 |

| SI-BMM | SI-BMM | Gual, D. M., Rendón, C. A., Alamilla, F. L., Cifuentes, R. P., & Lozano, R. A. T. (2013). Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña de México. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. | 3 |

| T004 | T004 | Barajas-Morales, J. (2001). Base de datos para la xiloteca del Instituto de Biología de la UNAM. (Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. T004). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| U011 | U011 | Santana-Michel, F. J., Cuevas-Guzmán, R., & Guzmán-Hernández, L. (2003). Actualización de la base de datos sobre la flora de la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra de Manantlán, Jalisco-Colima, México. Ciudad de México: Universidad de Guadalajara. | 1 |

| U048 | U048 | Guízar-Nolazco, E. (2004). Banco de datos florísticos del Herbario CHAP. (Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. U048). Ciudad de México: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. | 2 |

| Y004 | Y004 | Chiang-Cabrera, F. (2004). Inventario florístico de la región Calakmul-parte baja de la región Lacandona (cuenca alta del Usumacinta y Marqués de Comillas). (Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. Y004). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. | 1 |

| Y036 | Y036 | León-Cortés, J. L. (2005). Patrones de diversidad florística y faunística del área focal Ixcan, selva Lacandona, Chiapas. (Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO. Aves, proyecto No. Y036). Ciudad de México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. | 4 |

Two different GIS-based analyses were performed. The first one was carried out with FloraMap 1.03 software (Jones & Gladkov, 1999), with which probabilistic maps of its distribution, both general and of the different climatic regions where mamey sapote grows, were made; this is based on the construction of a dendrogram of accessions that grow in different climatic zones. The method used to construct the dendrogram was Ward's minimum variances (Ward, 1963). Probability maps were calculated without weighting; that is, all the coefficients of the climatic variables evaluated were equal to one. The transformation of precipitation data, to match them with the temperature scale, was done with the Rain Power A transform (Jones & Gladkov, 1999) with a coefficient of 0.5. In addition, six principal components that explained 95.52 % of the total variance were used (Jones & Gladkov, 1999; Jones et al., 2002). All FloraMap probabilistic maps were obtained with a minimum probability of 75 % to locate each species.

The second analysis was performed with the software DIVA-GIS version 7.5 (Hijmans et al., 2012). Two scenarios were considered to construct a model of climatic areas suitable for mamey sapote. In the first one, called current potential zones (CPZ), the accumulated real data for 50 years (1950-2000) were taken from the Worldclim (WC) database (Hijmans, Cameron, Parra, Jones, & Jarvis, 2005). In the second, named future potential zones (FPZ), data were modeled considering twice the atmospheric CO2 concentration to simulate global climate change, used in the CCM3 model (Govindasamy, Duffy, & Coquard, 2003).

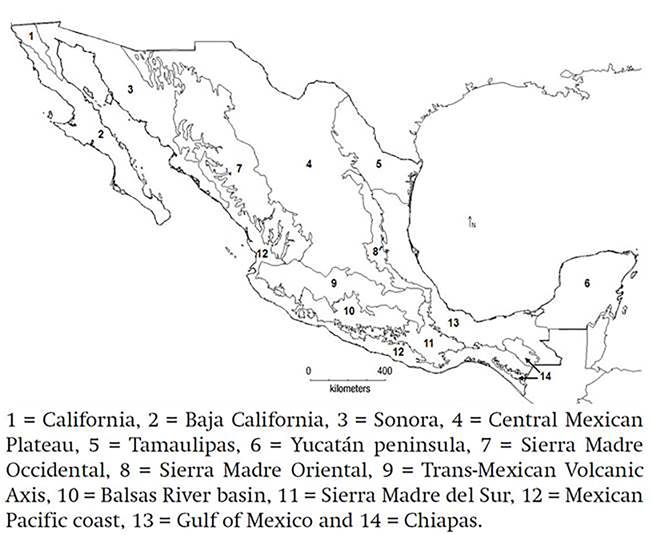

Both models were compared to locate the most suitable zones to establish in vivo germplasm banks, mother orchards and evaluation plots of mamey sapote; for this purpose, the Eco-Crop eco-climatic adaptation model was used (Hijmans, Guarino, Cruz, & Rojas, 2001; Hijmans & Graham, 2006). In addition, separate maps showing Mexico’s political boundaries and its biogeographic regions (Figure 1), the latter as described by Morrone (2005), were used for this analysis. These analyses take into account climatic data related to temperature and precipitation, but do not consider other factors such as wind or soil (Jones et al, 2002; Hijmans et al., 2012).

Results and discussion

Natural distribution

The mamey sapote in Mexico, according to the databases consulted, is distributed on the Pacific coast, from southern Sinaloa to Chiapas, and on the Gulf of Mexico coast, from Tamaulipas to Tabasco, as well as on the Yucatán peninsula, Morelos, southern Guanajuato, the southern part of the state of Mexico, southern Puebla, eastern San Luis Potosí, and northern Hidalgo and Querétaro (Figure 2). This location coincides with tropical and subtropical zones of Mexico. Its greatest probability of adaptation is mainly found in Veracruz, Campeche, Quintana Roo and Yucatán, where its probable center of origin is reported (Pennington & Sarukhán-Kermez, 2005). This information corresponds to that previously proposed by Villegas-Monter and Granados-Friely (2012), who recorded the presence of this species between 30 and 1,050 masl.

Eco-climatic characterization

The accessions considered in this study were divided into three climatic groups (Figure 3) that presented different distributions and climates, possibly associated with three different gene pools, which should be considered within the breeding programs. Under different environmental conditions, populations may have different genes of adaptation (Dobzhansky, 1970). One possible practical implication of this information in breeding programs is the development of hybrid varieties by considering different gene pools, since they are highly likely to obtain heterosis by crossing (Wright, 1978). For their part, the climatograms of the three groups (Figure 4a, 4b, 4c) showed that these have different climatic patterns.

Figure 3: Dendrogram of passport data of mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) using climatic variables.

Figure 4 Climatograms of the three eco-climatic groups as potential eco-regions of mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) distribution in Mexico (a, b, c) and comparison of mean temperature (d), precipitation (e) and the differential between the maximum and minimum temperatures (f) of the three climatic groups.

Group 1 was found on average at 115.2 masl, and had the smallest difference between the maximum and minimum temperature of the three groups and the lowest precipitation. Its annual rainfall accumulation was 1,586.9 mm and its average annual temperature was 23.5 °C, with an extreme minimum and maximum of 18.9 and 31.1 °C, respectively. The driest month had 33.8 mm of rainfall and the wettest 244 mm (Figure 4a). According to the Köppen classification modified by García (2004), these characteristics correspond to those of a warm subhumid climate with summer rains (Aw).

Group 2 was located on average at 235.3 masl and had the highest precipitation of the three groups. Its annual rainfall accumulation was 2,131.6 mm and its annual average temperature was 24.9 °C, having as an extreme minimum and maximum 16.6 and 32.8 °C, respectively. The driest month had 49.5 mm of rainfall and the wettest 358.5 mm (Figure 4b). According to the Köppen classification modified by García (2004), these characteristics belong to those of a warm humid climate with summer rains (Am).

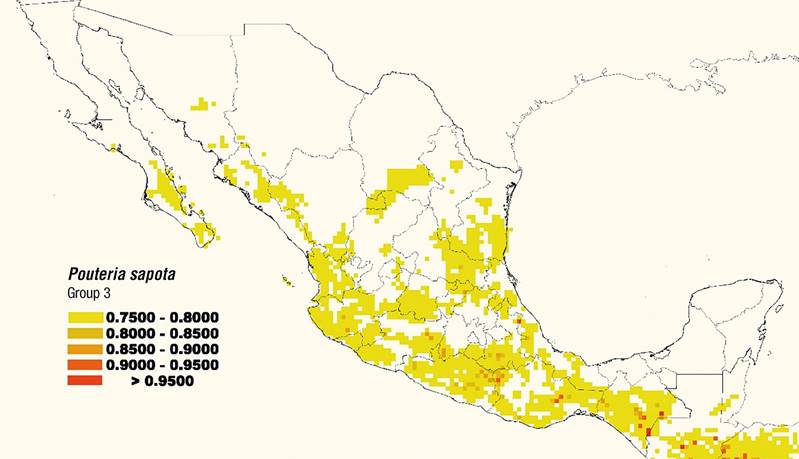

Group 3 was characterized by being found at 1,060.6 masl and by the lowest temperature of the three groups. Its annual rainfall accumulation was 1,605.9 mm and its average annual temperature was 20.8 °C, with its minimum and maximum being 12.5 and 28.8 °C, respectively. The driest month had 23.3 mm of rainfall and the wettest 281 mm (Figure 4c). According to the Köppen classification modified by García (2004), these are the characteristics of a semi-warm humid climate with summer rains [A(C)(m)].

When comparing the climatic factors, Group 3 presented the lowest mean temperature (Figure 4d), Group 2 the highest precipitation (Figure 4e) and Group 1 the smallest difference between the minimum and maximum temperature (Figure 4f). This information constitutes an important reference for the selection of specific genotypes for each climatic group; this is due to the benefit represented by its satisfactory adaptation and competitiveness, especially considering the presence of local materials in each of the eco-climatic regions where mamey sapote is distributed (Zagaja, 1988).

Guayaba (Psidium guajava L.) has two gene pools, one tropical and one subtropical (Cázares-Sánchez et al., 2010), and it has been observed that tropical materials are more susceptible to frost (Mondragón-Jacobo, Toriz-Ahumada, & Guzmán-Maldonado, 2010). Rajan, Yadava, Kumar, and Saxena (2007) indicate that improving crops requires a reserve of genes that are naturally protected in the genetic diversity of each species. In this sense, cultivars may not have a good adaptation to more than one of the eco-climatic regions (Cázares-Sánchez et al., 2010; Núñez-Colín & Goytia-Jiménez, 2009). Therefore, identifying and selecting specific mamey sapote materials for each eco-climatic region will enable finding desirable genes to incorporate into the cultivars, including those related to resistance to pests, diseases and abiotic factors, as well as to improving fruit quality and productivity (Callahan, 2003; Quamme & Stushnoff, 1988; Sistrunk & Moore, 1988).

The genetic hybridization method may be an option for mamey sapote. This is due to the fact that this species is allogamous (Villarreal-Fuentes et al., 2015) and by interbreeding individuals with different genotypes, due to their adaptation to the environment, they would be expected to produce hybrids with high heterosis (Bringhurst, 1988; Hansche, 1988; Wright, 1978). This requires that the breeding programs be established in the three regions found in the eco-climatic characterization to optimize the response to the selection of the candidate genotypes to be cultivars in Mexico. Balerdi and Crane (2015) report various selections suitable for Florida conditions, which should be tested in different regions of Mexico, especially in the distribution areas feasible for Group 1 since most were selected in the Caribbean.

Group 1 is mainly found on the Yucatán peninsula, with some atypical points in Veracruz, Guerrero and Sinaloa (Figure 5). Group 2 covers the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche and Chiapas, as well as the Pacific coast with a segmented distribution in Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas (Figure 6). Group 3, which covers the largest area, comprises mainly the northern Gulf of Mexico (Tamaulipas) and the entire Pacific region, from southern Sonora to Chiapas, including some points in Baja California Sur (Figure 7). In addition, Group 3 showed a probable distribution in the central north of the country (Durango, Coahuila and Zacatecas), as well as in southwestern Guanajuato, Morelos, southern Puebla, eastern San Luís Potosí, and northern Querétaro and Hidalgo (Figure 7).

Figure 5 Estimated distribution map of Group 1 (climate Aw) of mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq. ] H. E. Moore & Steam) in Mexico.

Figure 6 Estimated distribution map of Group 2 (climate Am) of mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) in Mexico.

Figure 7. Estimated distribution map of Group 3 [climate A(C)(W) of mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) in Mexico.

This suggests that it is necessary to generate and select specific cultivars for each eco-climatic region (Cázares-Sánchez et al., 2010; Rajan et al., 2007; Zagaja, 1988), since the obtaining of ideal cultivars in one of the regions does not guarantee their adaptability in the others (Quamme & Stushnoff, 1988). To confirm the inferred existence of different gene pools, according to the groups found by environmental characteristics, morphological and molecular characterization studies are required. It would be advisable to carry out an ethnobotanical study to determine the role of human beings in the distribution of mamey sapote in the three eco-climatic regions found in this work.

Modeling of current potential zones and with the climate change scenario

The Eco-Crop model considered that the mamey sapote growth cycle is 365 days, which is why it shows no lethargy. Additionally, some of the conditions found for this species with Eco-Crop include: extreme temperatures of 15 and 36 °C, optimum minimum and maximum temperatures of 24 and 30 °C, respectively, extreme rainfall patterns of 800 and 4,000 mm, optimum minimum and maximum rainfall patterns of 2,000 and 3,300 mm, respectively, and death temperature in the early stages of 0 °C. Using these data, the following adaptation zones were modeled: excellent, very good, good, marginal, very marginal and unsuitable.

In the CPZ maps it was found that the regions with excellent adaptation, according to the 14 regions described by Morrone (2005), are located on the Mexican Pacific coast, along the Gulf of Mexico, on the Yucatan peninsula and at some isolated points in the Balsas River basin (Figure 8). Specifically, the mamey sapote is found in Tabasco and the adjoining part of Campeche, on the coast of Chiapas, several regions on the coast of Guerrero and Jalisco, the west coast of Oaxaca and in some areas in southern Veracruz (Figure 8).

Left: the biogeographic zones of Mexico; right: the political division of Mexico.

Figure 8 Eco-Crop model for mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota [Jacq.] H. E. Moore & Steam) in Mexico, with current data.

In the FPZ there is an enlargement of the regions with excellent adaptation (Figure 9), mainly in the Balsas River basin and on the Gulf of Mexico. Based on the scenario projected to 2050, it was found that the potential states for producing mamey sapote, according to their degree of adaptation, will be: Tabasco, Chiapas, Veracruz, Guerrero, Campeche, Jalisco, Oaxaca, Nayarit, Quintana Roo, Colima, Michoacán, Morelos, Puebla, San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo (Figure 9). That is, there is a possibility of good to excellent adaptation for the cultivation of mamey sapote in 15 of Mexico’s 32 states, several of them included in the official statistics of 2014 (SIAP, 2015). The current production zones could be expanded to other potential regions described in this paper as FPZ (Figure 9), which could strengthen the cultivation of mamey sapote in Mexico.

Conclusions

Three eco-climatic regions were identified for mamey sapote cultivation in Mexico, corresponding to climates Aw, Am and A(C)(m). The best places to grow this species are found along the coast of Chiapas, in several regions on the coast of Guerrero and Jalisco, on the west coast of Oaxaca, in Tabasco, western Campeche and some areas in southern Veracruz, which are distributed among four different biogeographic regions.

The climate change scenario shows a better adaptation of this species in Mexico.

texto en

texto en