Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias geológicas

On-line version ISSN 2007-2902Print version ISSN 1026-8774

Rev. mex. cienc. geol vol.27 n.3 Ciudad de México Dec. 2010

The oldest record of Equini (Mammalia: Equidae) from Mexico

El registro más antiguo de Equini (Mammalia: Equidae) de México

Victor M. Bravo–Cuevas1* and Ismael Ferrusquía–Villafranca2

1 Museo de Paleontología, Area Académica de Biología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Ciudad Universitaria s/n, Carretera Pachuca–Tulancingo km 4.5, CP 42184, Pachuca, Hidalgo, México. *Correo electrónico: vbravo@uaeh.edu.mx

2 Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, CP 04510, México D.F., México.

Manuscript received: April 21, 2010.

Corrected manuscript received: September 3, 2010.

Manuscript accepted: September 8, 2010.

ABSTRACT

Equine material recovered from the Middle Miocene El Camarón andMatatlán Formations (both K–Ar dated ca. 15 Ma, late Early Barstovian) of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico, is formally described. It consists of isolated upper and lower cheek teeth, whose occlusal patterns and tooth dimensions closely resemble those of Pliohippus, although no positive specific identification is warranted on this basis. Pliohippus sp. from Oaxaca is contemporary with P. mirabilis (late Early–Late Barstovian of Nebraska, Colorado and Florida), the oldest and most plesiomorphic species of the genus. These facts are very significant on several counts: Biogeographically, the Oaxacanfind extends the Barstovian/Middle Miocene record of Pliohippus from the Northern Great Plains and the Gulf Coast ofthe coterminous United States to southeastern Mexico, some 2000 km and at least 10° latitude degrees apart. Phyletically, it gives additional evidence that the differentiation of Pliohippus occurred during the Early Barstovian at least. Paleoecologically, it shows that Pliohippus could thrive both in temperate and tropical environmental settings, either of which could have been the site of such phyletic differentiation. Finally, Pliohippus sp. from Oaxaca is the oldest record of the tribe Equini in México, antedating by ~6–8 Ma the extensive occurrence of e0uines during the Hemphillian–Blancan of this country.

Key words: equines, Middle Miocene, Oaxaca State, southeastern Mexico.

RESUMEN

En el presente estudio se describe formalmente el material de equines recuperado de estratos pertenecientes a las formaciones El Camarón y Matatlán (ambas datadas por K–Ar en aproximadamente 15 Ma, parte tardía del Barstoviano Temprano) del Mioceno Medio de Oaxaca en el sureste de México. El material consistió en un conjunto de molariformes superiores e inferiores aislados con un tamaño y patrón oclusal estrechamente cercanos a los del género Pliohippus; sin embargo, la calidad de la muestra disponible imposibilita precisar su identidad específica. El registro oaxaqueño de Pliohippus sp. es contemporáneo a P. mirabilis de la parte más tardía del Barstoviano temprano y Barstoviano tardío de Nebraska, Colorado y Florida; esta última especie es la más plesiomórfica y antigua incluida en el género. Esta evidencia en conjunto es relevante en los siguientes aspectos: Biogeográficamente, el equine oaxaqueño extiende por aproximadamente unos 2000 km y 10° de latitud el registro del género Pliohippus, desde las Grandes Planicies y Planicie Costera del Golfo en Estados Unidos hasta el sureste de México durante el Mioceno Medio (Barstoviano). Filéticamente, proporciona evidencia adicional acerca de la diferenciación de Pliohippus al menos durante el Barstoviano temprano. Paleoecológicamente, el registro oaxaqueño indica que Pliohippus habitó en zonas de Norteamérica templada y Norteamérica tropical, regiones en las cuales potencialmente se presentó la diferenciación filética del género. Finalmente, Pliohippus sp. de Oaxaca se convierte hasta ahora en el representante más antiguo de la Tribu Equini en México, dado que antecede por aproximadamente 6 a 8 Ma al extenso registro de equines del Henfiliano–Blancano del país.

Palabras clave: equinos, Mioceno Medio, Oaxaca, sureste de México.

INTRODUCTION

The Equini, a monophyletic lineage of tribal rank, is a group of medium– to large– sized monodactyl–footed horses, whose upper cheek teeth have protocones connected to the protoloph. Tribe Equini includes Equus, the only extant genus of the suborder Hippomorpha sensu McKenna and Bell, 1997 (MacFadden, 1992, 1998). The Equini comprises "Pliohippus" tehonensis, certain species assigned to "Dinohippus" (e.g., "D." leardi, "D." interpolatus, and "D." mexicanus), Parapliohippus, Heteropliohippus, Pliohippus, Astrohippus, Dinohippus, Equus, Onohippidium, and Hippidion (Kelly, 1995, 1998); the last two genera were regarded for a long time as South American endemics, however MacFadden and Skinner (1979) documented their occurrence in North America as well.

Pliohippus was a dominant equine horse during the Middle and Late Miocene of North America, roaming extensively from the California Coastal Ranges, the Great Basin, and the Great Plains, to the Gulf Coastal Plain (MacFadden, 1998). The systematics of Pliohippus has been intensively discussed regarding: (1) the taxonomic and phylogenetic value of the preorbital facial fossa; and (2) the potential importance of Pliohippus as a close relative of Equus (Webb, 1969; MacFadden, 1984, 1986; Azzaroli, 1988; Prado and Alberdi, 1996). To properly assess Pliohippus relative to taxonomic identification of the Oaxacan material, we briefly summarize the historical taxonomy of this genus.

Marsh (1874) erected the Genus Pliohippus to include a partial skeleton from the Early Clarendonian North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA) of Nebraska (Niobrara River area), Great Plains; the genotypic species was named Pliohippus pernix. Later, Osborn (1918) in his iconographic revision of the late Tertiary North American horses described sixteen nominal species of Pliohippus, including two new ones, P. nobilis and P. leidyanus. Stirton (1940) made the next major change, placing most of the Osborn species in the subgenera P. (Pliohippus) and P. (Astrohippus), except the Pliocene–Pleistocene species P. simplicidens and P. cumminsii, now transferred to Equus within the subgenera E. (Plesippus) and E. (Asinus) respectively (Scott, 2004); Stirton (1940) added six nominal species to Pliohippus. Later, Quinn (1955) raised Astrohippus to generic rank.

During the last decades, cladistics played a major role in reassessing phylogenetic relationships not only in fossil horses, but practically in all groups. Within this context, Hulbert (1989, 1993) and Hulbert and MacFadden (1991) regarded Pliohippus as a single anagenetic lineage comprising the three successive species: P. mirabilis from the Late Barstovian NALMA of California, the Gulf Coast, and the Great Plains; P. pernix from the Clarendonian NALMA of the Southern Great Basin and the Great Plains; and P. nobilis from the Early Hemphillian NALMA of the Great Plains (MacFadden, 1998). The other species previously assigned to Pliohippus were either synonymized to any of these three, or were transferred to other genera. Recently, the cladistic analyses of Kelly (1995, 1998) led him to propose that Pliohippus is a monophyletic group that includes Pliohippus pernix (the type species), P. mirabilis, P. nobilis, P. tantalus, P. fossulatus, and P. sp. cf. P. fossulatus from the Clarendonian of California and Texas. Notice that "Pliohippus" tehonensis, although showing some morphological similarities to Pliohippus, can not be formally assigned to this genus, because this results in paraphyly (Kelly, 1998). In summary, it appears that currently, based upon material records from the coterminous United States, Pliohippus is represented by at least five late Neogene species.

The history of this genus in Mexico and Central America is rather limited, and unfolded in consonance with that presented above. A extensive revision (Lance, 1950) of the horses from the Hemphillian of Yepómera, Chihuahua, northern Mexico, included two then new species, Pliohippus (Pliohippus) mexicanus and P. (Astrohippus) stockii. MacFadden (1984, 2006) respectively transferred them to the genera Dinohippus and Astrohippus. Working in Central America, Olson and McGrew (1941) described and named Pliohippus hondurensis, a new species from the Early Hemphillian of Honduras. Additional horse material was later described by Webb and Perrigo (1984), who upheld the taxonomic assignment of Olson and McGrew; however, Hulbert (1988) reassigned it to Calippus hondurensis.

The Middle Miocene continental strata from Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico, have over the years yielded a very diverse mammal assemblage (cf. Stirton, 1954; Wilson, 1967; Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1990, 2003; Jiménez–Hidalgo et al., 2002), of interest on account of its intermediate position between Central America and North America proper. The assemblage includes horses, of which some have already been monographed (cf. Bravo–Cuevas and Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 2006, 2008). The present study describes the equine material from the Matatlán and El Camarón Formations of Oaxaca, which constitutes the oldest record of this tribe and the first record of Pliohippus from Mexico, and discusses its paleobiological significance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The equine material from the Middle Miocene of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico, consists of 15 isolated cheek teeth and three associated dental series; the dental sample is housed at the Colección Nacional de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. The dental terminology is that of MacFadden (1984, fig. 4, p. 17). For each cheek tooth, a set of morphological and metric characters of systematic value (MacFadden, 1984; Hulbert, 1988, 1989; Hulbert and MacFadden, 1991; Kelly, 1995, 1998) were evaluated. The dental measurements were taken with a General MG electronic digital caliper with a measuring range 0–150 mm, 0.01 mm of resolution, and 0.003 mm of accuracy. The curvature for each upper cheek teeth (outlined by the mesostyle) was measured following Downs (1961, p. 44–45).

The wear stage for each cheek teeth was established following Kelly (1998, p. 1–2). Because the dental oc–clusal morphology of equid teeth is subject to ontogenetic variation, dental comparison of the Mexican specimens to those of other selected North American pliohippine species was done at equal wear stage; in this instance, some of the studied specimens were cross–sectioned to disclose virtual wear stages.

The taxonomic identity of the Oaxacan dental sample was assessed by comparison with Pliohippus specimens housed in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York; the University of California, Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, California; and the Florida Museum of Natural History at University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

The abbreviations used in this study are as follows: AMNH, American Museum of Natural History; IGM, Colección Nacional de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; UCMP, University of California Museum of Paleontology; UF, Vertebrate Paleontology Collection, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville; APL/apl, anteroposterior length upper/lower dentition; CH/ch, me–sostyle crown height upper/metastylid crown height lower dentition; HI, hipsodonty index; L, left; M/m, upper/lower molar; mml, metaconid–metastylid length; P/p, upper/lower premolar; PRL, protocone length; PRW, protocone width; RC, radius of curvature; R, right; TRW/trw, transverse width upper/lower dentition.

STUDY AREAS AND GEOLOGIC SETTING

The fossil localities occur within the Matatlán and Nejapa areas in Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico. The Matatlán area lies on the eastern part of the Valles Centrales, some 20 km east of Oaxaca City, between 16°50' – 17°00'N and 96°15' – 96°30'W. The Nejapa area is set northwest of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, roughly midway between the cities of Oaxaca and Tehuantepec, between 16°30° – 16°40'N and 95°55' – 96°10'W (Figure 1).

The fossil horse material was recovered from sedimentary sequences that belong to the synorogenic, tuffaceous, fluvio–lacustrine Matatlán Formation (Matatlán Area) and El Camarón Formation (Nejapa Area), both K–Ar dated at ~15 Ma (Ferrusquía–Villafranca and McDowell, 1991; Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1992; Tedford et al., 2004). Both the radiometric dates of the rock units and the biogeochronologic range of the known mammal taxa indicate a late Early Barstovian age (Jiménez–Hidalgo et al., 2002; Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 2003; Tedford et al., 2004).

The Matatlán Formation consists of friable to moderately indurated, thin to medium bedded tuffaceous sandstones, sparsely interbedded by felsic tuffs, bentonitic clay and polymictic conglomerate. On the other hand, the El Camarón Formation includes friable to moderately indurated tuffaceous siltstone, sandstone and conglomerate (Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1990, 2002).

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Family Equidae Gray, 1821

Subfamily Equinae Gray, 1821

Tribe Equini Gidley, 1907

Genus Pliohippus Marsh, 1874

Pliohippus sp.

Material examined. Matatlán Area: IGM 6721, RP3 or RP4; IGM 6722, RM1; IGM 6723, RM1 or RM2; IGM 6724, LM1 or LM2. Nejapa Area: IGM 7975, RP4; IGM 6725, RP3 or RP4; IGM 6726, RM1 or RM2; IGM 6727, RM2; IGM 6728, right mandibular fragment with p4–m2; IGM 6729, RM2; IGM 6730, LM1; IGM 6731, Lp2; IGM 6732, Rp2; IGM 6733, Lm1 or Lm2; IGM 6734, composite right dental series with p4–m2; IGM 6735, Rp4; IGM 6736, Rm1; IGM 6737, Rm2; IGM 6738, Rp4 or Rm1; IGM 6739, RP4.

Occurrence. Matatlán Fauna and Nejapa Fauna, late Early Barstovian of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico.

Description. Upper dentition. The upper cheek teeth are hypsodont (HI = 1.9), strongly curved (RC from 30 to 40 mm), and covered by a thick layer of cement (~1.5 mm thick). The little worn molar mesostyle crown height is ca. 50 mm (Table 1). The protocone is oval (PRL /PRW ratio of 1.5 – 2.0) and connected to the protoloph along the crown height. The external and internal fossette borders are very simply plicated (Figure 2).

In P3 and P4 the parastyle and mesostyle are rounded and well developed, the metastyle is less evident. The internal fossette margins are very simple plicated, with only a single pli prefossette and a single pli postfossette observed; these plications are shallow and immediately disappear during the early wear stages. The pli protoconule is well developed in early wear, decreasing in size in early moderate wear stages. The pli protoloph is absent and the pli hypostyle is rudimentary. The protocone is oval and connected to the protoloph near the base of the crown. The protocone lingual border is straight and the protocone long axis is set in an anteroposterior direction. The anterior border of the proto–cone is rounded, whereas the posterior border is angular. The pli caballin is simple, small (ca. 2 mm), and non persistent (worn away in early wear stage); only in IGM 6739 is the pli caballin well developed. The hypoconal groove is narrow, open during the early wear stages and closed in early moderate to moderate wear stages. The hypoconal groove commonly forms an isolated lake when it closes.

The molar occlusal pattern is comparable to that of premolars, differing only in the absence of plis caballin. In IGM 6727 (the only M3) the pli caballin is simple, small, and non persistent.

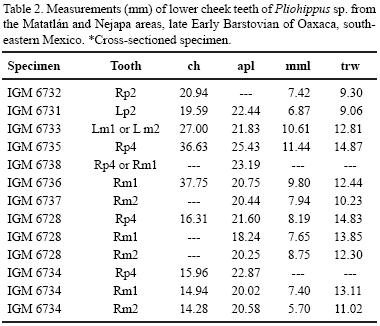

Lower dentition. The lower cheek teeth are also covered by a thick layer of cement (~1.5 mm thick). The metastylid crown height during early wear stages is ca. 40 mm (Table 2). The protoconid and hypoconid are rounded to sub–rounded. The metaconid–metastylid complex is expanded, but not elongated (mml of p4 ≈ 50 % apl). The metaconid and metastylid are rounded and sub–equal in size on the premolars, but the metaconid is larger than the metastylid on molars. The protostylid appears near the crown base as a small anterior cingulid. The linguaflexid is V–shaped in the premolars and U–shaped in the molars. The pli entoflexid is absent. The ectoflexid does not penetrate the isthmus in p2 (i.e., is shallow), but partially penetrates the isthmus in p3 –m2 (i. e., is moderately deep). The pli caballinid is absent in premolars and molars. The entoconid is rounded, well developed, and well separated to hypoconulid (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The oclusal patterns of the Oaxacan cheek teeth are similar to those of Pliohippus in having the following particular suite of characters: (a) hypsodont and strongly curved upper cheek teeth (RC <40 mm); (b) fossettes very simply plicated; (c) unusual single, and non– persistent plis cabal–lin; (d) protocone connected with protoloph throughout the crown height; (e) hypoconal lakes commonly formed with closure of hypoconal grooves; (f) preflexid and postflexid enamel borders simple; (h) moderately deep ectoflexid on premolars; (i) metastylid notably smaller than metaconid on molars (Kelly, 1995, 1998).

As summarized in Table 3, the Oaxacan cheek teeth differ in several respects from those of other related Middle Miocene horses, including Acritohippus from the Late Hemingfordian of California and Nebraska and the Barstovian of California, Florida, Nebraska, Oregon, Nevada, and Montana; Parapliohippus from the Late Hemingfordian of California; and Heteropliohippus and "Pliohippus " tehonensis, both from the Early Clarendonian of California. The cheek teeth of Acritohippus are distinguished from the Oaxacan cheek teeth by having (a) small mesostyle crown heights (ca. 30 mm), (b) protocones connected to protoloph in early moderate wear, (c) absent hypoconal lake, (d) metaconid and metastylid equal or subequal in size on molars, and (e) ectoflexid that fully penetrates the isthmus on premolars (Table 3). The cheek teeth of Parapliohippus differ from those of the Oaxacan cheek teeth as follows: (a) subhypsodont (CH ca. 25 mm),

(b) have a thin layer of cement (this condition is also observed in Heteropliohippus), and (c) ectoflexids that fully penetrate the isthmus on premolars (Table 3). On the other hand, Heteropliohippus and "Pliohippus" tehonensis cheek teeth differ from those of the Oaxacan pliohippine in these features: (a) Moderately curved upper cheek teeth (RC > 40 mm), (b) protocones connected to protoloph in early to early moderate wear, (c) plis caballin commonly present on molars, (d) lack of hypoconal lake on M1–M2, and (e) lower cheek teeth with moderately well developed protostylids (Table 3).

The occlusal pattern of Pliohippus cheek teeth is largely similar across species, so that only a few dental characters actually vary, such as the mesostyle crown height, and the presence/absence of plis caballin. The mesostyle crown height of the Oaxacan cheek teeth (ca. 50 mm) is comparable to that of dental specimens referred to P. pernix including UCMP 32253A (LP3 or P4, CH = 48 mm), and UCMP 35454A (RP3 or P4, CH = 50 mm) (Webb, 1969, tab. 18); a similar condition occurs in dental specimens of P. tantalus, such as UCMP 19434 (LP4, CH = 48 mm; Osborn, 1918, fig. 130). The species P. mirabilis and P. fos–sulatus have a similar crown height, whereas P. nobilis is distinguished by having even higher crowned cheek teeth (CH > 58 mm, Kelly, 1998).

The cheek teeth of Pliohippus mirabilis (e.g. LP3 and LP4 of AMNH 9096, a cranium; Osborn, 1918, fig. 88), P. pernix (e.g. right and left P3 and P4 of UCMP 32285, a palate with right and left P3–M3; Webb, 1969, fig. 23), P. nobilis (e.g. LP3 and LP4 of AMNH 2668, a skull fragment with left P3–M3 and right P2–M3; Osborn, 1918, fig. 128), P. tantalus (e.g. LP4, UCMP 19434; Osborn, 1918, fig. 130), and the Oaxacan teeth (IGM 6725, IGM 6721, IGM 6739) each show a single pli caballin; however, the pli caballin is commonly absent in P. fossulatus (Kelly, 1998).

A dental character condition shared by all species of Pliohippus is the hypoconal groove closure in early wear stages (Kelly, 1998, Appendix E). The Oaxacan specimens IGM 6721 and IGM 6725 depart from this general condition, because the hypoconal groove closes in moderate– and late– wear stages respectively. It should be noted that similar conditions are observed in isolated cheek teeth referred to Pliohippus from the Late Barstovian of Florida, such as UF 102101 (RM1 or RM2), UF 102103 (LP3 or LP4), and UF 131909 (LP4). This fact suggests that some Barstovian populations of Pliohippus retained a less–derived timing of hypoconal groove closure condition (see Hulbert and MacFadden, 1991; Kelly, 1995, 1998).

By the same token, the Oaxacan cheek teeth here referred to Pliohippus are lower crowned than those of P. nobilis, and differ from those of P. fossulatus in having more persistent plis caballin; yet their overall occlusal pattern and size range of their teeth readily correspond to those observed in all other species of Pliohippus. This is not surprising given this genus' extremely homogeneous dental morphology, which shifts species recognition/characterization to other features, so that Pliohippus species are mainly distinguished on the dorsal preorbital fossa and/or malar fossae configuration(s) (cf. MacFadden, 1984; Azzaroli, 1988; Kelly, 1995, 1998).

Summing up then, the odontography of Oaxacan cheek teeth closely resembles that of Pliohippus; however, the lack of associated cranial material, and the fact that dental features alone are no longer suitable means to establish species identity within this genus, constrains us to assign the studied cheek teeth suite to Pliohippus sp.

COMMENTS ON PALEOBIOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Pliohippus mirabilis is regarded as the oldest and morphologically most plesiomorphic species of Pliohippus (Kelly, 1998); it is recorded from the late Early Barstovian–Late Barstovian NALMA (ca. 12–15 Ma) of the Great Plains (Nebraska and Colorado), and the Gulf Coastal Plain (Florida; Hulbert and MacFadden, 1991; Kelly, 1998). Pliohippus sp. from the late Early Barstovian (ca. 15 Ma) of southeastern Mexico (Oaxaca) is a chrono–correlative of P. mirabilis, in spite of the 2000 km distance and 10° latitude difference that separates their known geographic distributions, thus extending southward by that much the geographic occurrence of Pliohippus in particular, and that of the tribe Equini overall during the Middle Miocene. This fact by itself is quite significant on several grounds. First, it indicates that Pliohippus was able to thrive both in temperate and tropical environmental settings, and so should have been fairly eurytopic rather than stenotopic. In turn, this implies that the phylogenetic differentiation of Pliohippus could have taken place either in temperate or in tropical North America. Our observations also provided additional support that the genus Pliohippus became phylogenetically differentiated by late Early Barstovian NALMA time at least. Biogeographically, Pliohippus sp. from Oaxaca is the southernmost record of Middle Miocene Equini in North America (Figure 4).

Prior to this report, the Equini from Mexico were known from the Hemphillian and Blancan of several morphotectonic provinces (hitherto MP, Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1993): Astrohippus stockii and Dinohippus mexicanus have been found in the Chihuahua–Coahuila Plateaus and Ranges MP (= CH–CO) (Yepómera, Chih., Lance, 1950; Lindsay, 1984; Lindsay et al., 2006; MacFadden, 2006), the Central Plateau MP (= CeP) (San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas, Carranza–Castañeda, 2006), and the Trans–Mexican Volcanic Belt MP (= TMVB) (Jalisco, Montellano–Ballesteros, 1997; Carranza–Castañeda et al., 2002; Guanajuato, cf. Carranza–Castañeda, 2006; Carranza–Castañeda and Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1978; Carranza–Castañeda and Miller, 1998). "Dinohippus" interpolatus occurs in the TMVB (Jalisco, Guanajuato and Hidalgo, Miller and Carranza–Castañeda, 1984; Carranza–Castañeda, 2006, reported as Dinohippus interpolatus), and Equus (Plesippus) simplicidens (reported as E. (Dolichohippus) simplicidens) from the Blancan of the CH–CO MP, TMVB MP (Carranza–Castañeda, 2006), and the Peninsula de Baja California MP (southern end, Miller, 1980).

The reconnaissance of Pliohippus sp. from Oaxaca geographically extends southward the Equini record from the Trans–Mexican Volcanic Belt to the Sierra Madre del Sur MP, and establishes equines in a tropical environment. Biogeochronology pushes tribe Equini back in time some six Ma, from the Hemphillian to the late Early Barstovian; this is the oldest known equine record of Mexico (Figure 5).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A suite of cheek teeth from the Middle Miocene (late Early Barstovian) Matatlán and El Camarón Formations of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico, is formally described and assigned to Pliohippus sp. The Oaxacan equine record is contemporaneous to Pliohippus mirabilis, the geologically oldest and most plesiomorphic species this genus. These facts are very significant on several grounds: Biogeographically, it extends southward some 2,000 km and at least 10° latitude degrees the Middle Miocene range of the Equini from temperate North America (Northern Great Plains and easternmost Gulf Coastal Plain) to tropical North America (southeastern Mexico). Paleoecologically, it shows that Pliohippus could thrive both in temperate and tropical environmental settings. Phylogenetically, it suggests that the differentiation of Pliohippus probably occurred during the Early Barstovian (16–15 Ma), either temperate or tropical North America. Biogeochronologically, it pushes the Mexican Equini record back in time some six m.y. from the Hemphillian to the late Early Barstovian, making it the oldest Equini record of Mexico.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Eric Scott and to the anonymous reviewer for critically reviewing the manuscript, their comments and suggestions greatly improved the present report. The senior author wish express special thanks to Bruce J. MacFadden and Richard C. Hulbert Jr., for their valuable comments on late Neogene horses during his visit to the Florida Museum of Natural History. The visit was supported by the 2003 International Student Travel Grant to Study the Vertebrate Paleontology Collection at the Florida Museum of Natural History. The junior author thanks to the Dirección General de Asuntos de Personal Académico de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, for supporting field work expenses through Grant PAPIIT IN–115606.

REFERENCES

Azzaroli, A., 1988. On the equid genera Dinohippus Quinn 1955 and Pliohippus Marsh 1874: Bolletino della Societa Palaeontologica Italiana, 34, 205–221. [ Links ]

Bravo–Cuevas, V.M., Ferrusquía –Villafranca, I., 2006, Merychippus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of the State of Oaxaca, Southeastern Mexico: Geobios, 39, 771–784. [ Links ]

Bravo–Cuevas, V.M., Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 2008, Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of Oaxaca, Southeastern Mexico: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 28(1), 243–250. [ Links ]

Carranza–Castañeda, O., 2006, Late Tertiary fossil localities in Central Mexico between 19°–23° N, in Carranza–Castañeda, O., Lindsay, E.H. (eds.), Advances in Late Tertiary Vertebrate Paleontology in Mexico and the Great American Biotic Interchange: México, D.F., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología y Centro de Geociencias, 45–60. [ Links ]

Carranza–Castañeda, O., Ferrusquia–Villafranca, I., 1978, Nuevas investigaciones sobre la fauna Rancho el Ocote, Plioceno Medio de Guanajuato, México, Informe preliminar: Revista del Instituto de Geología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2(2), 163–168. [ Links ]

Carranza–Castañeda, O., Miller, W.E., 1998, Paleofaunas de vertebrados en las cuencas sedimentarias del Terciario tardío de la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana, in Carranza–Castañeda, O., Córdoba–Méndez, O. A. (eds.), Avances en Investigación, Paleontología de Vertebrados: Pachuca, Hidalgo, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Tierra, Publicación Especial, 85–95. [ Links ]

Carranza–Castañeda, O., Miller, W.E., 2004, Late Tertiary terrestrial mammals from Central Mexico and their relationship to South American inmigrants: Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 7(2), 249–261. [ Links ]

Carranza–Castañeda, O., Miller, W.E., Kowallis, B., 2002, La Cuenca de Tecolotlán, una nueva fauna del Terciario Tardío de la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana (resumen), in Reunión Anual de la Unión Geofísica Mexicana, Geos (Resúmenes y Programa), 22(2), 331. [ Links ]

Downs, T., 1961, A study of variation and evolution in Miocene Merychippus: Contributions in Science, 45, 75. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 1990, Biostratigraphy of the Mexican continental Miocene: Part II, The Southeastern (Oaxacan) faunas: Paleontología Mexicana, 56, 57–109. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 1992, Contribución al conocimiento del Cenozoico en el Sureste de México y de su relevancia en el entendimiento de la evolución geológica regional (resumen), in VIII Congreso Geológico Latinoamericano, Salamanca, España: 4,40–44. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 1993, Geology of Mexico: a sinopsis, in Ramamoorthy, T.P., Bye, R., Lot, A., Fa, J. (eds.), Biological Diversity of México: Origins and Distribution: New York, USA, Oxford University Press, 3–107. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 2002, Contribución al conocimiento geológico de Oaxaca: El Área Nejapa de Madero, México: Boletín del Instituto de Geología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 112, 1–110. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 2003, México's Middle Miocene mammalian assemblages: An overview: American Museum of Natural History Bulletin, 13, 231–347. [ Links ]

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., McDowell, F. W. 1991, The Cenozoic sequence of selected areas in Southeastern Mexico, its bearing in understanding regional basin development there (resumen), in II Convención sobre la evolución geológica de México, Pachuca, Hidalgo, 1,45–50. [ Links ]

Gidley, J.W., 1907, Revision of the Miocene and Pliocene Equidae of North America: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 23, 865–934. [ Links ]

Gray, J.E., 1821, On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals: London Medical Repository Review, 15, 296–310. [ Links ]

Hulbert, R. C. Jr. , 1988, Calippus and Protohippus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Miocene (Barstovian–Early Hemphillian) of the Gulf Coastal Plain: Florida State Museum Biological Sciences Bulletin, 33, 221–340. [ Links ]

Hulbert, R.C. Jr., 1989, Phylogenetic interrelationships and evolution of North American Late Neogene Equinae, in Prothero, D. R., Schoch, R. M. (eds.), The Evolution of Perissodactyla: New York, USA, Oxford University Press, 176–193. [ Links ]

Hulbert, R.C. Jr., 1993, Taxonomic evolution in North American Neogene horses (Subfamily Equinae): the rise and fall of an adaptive radiation: Paleobiology, 19, 216–234. [ Links ]

Hulbert, R.C. Jr., MacFadden, B.J. , 1991, Morphological transformation and cladogenesis at the base of the adaptive radiation of Miocene hypsodont horses: American Museum Novitates, 3000, 1–61. [ Links ]

Jiménez–Hidalgo, E., Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I, Bravo–Cuevas, V.M., 2002, El registro mastofaunístico miocénico de México y sus implicaciones paleobiológicas, in Montellano–Ballesteros, M. , Arroyo–Cabrales, J. (eds.), Avances en los estudios paleomastozoológicos: México, D. F., Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 47–58. [ Links ]

Kelly, T.S., 1995, New Miocene horses from the Caliente Formation, Cuyama Valley Badlands, California: Contributions in Science, 455, 1–33. [ Links ]

Kelly, T.S., 1998, New Middle Miocene equid crania from California and their implications for the phylogeny of the Equini: Contributions in Science, 473, 1–43. [ Links ]

Lance, J.F., 1950, Paleontología y estratigrafía del Plioceno de Yepómera Estado de Chihuahua. Parte 1: Équidos, excepto Neohipparion: Boletín del Instituto de Geología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 54, 1–81. [ Links ]

Lindsay, E.H., 1984, Late Cenozoic mammals from northwestern México: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4(2), 208–215. [ Links ]

Lindsay, E.H., Jacobs, L.L., Tessman, N.D., 2006, Vertebrate fossils from Yepómera, Chihuahua, Mexico, in Carranza–Castañeda, O., Lindsay, E.H. (eds.), Advances in Late Tertiary Vertebrate Paleontology in Mexico and the Great American Biotic Interchange: México, D.F., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología and Centro de Geociencias, 19–32. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B.J., 1984, Astrohippus and Dinohippus from the Yepómera local Fauna (Hemphillian, Mexico) and implications for the phylogeny of one–toed horses: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4(2), 273–283. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B.J., 1986, Late Miocene monodactyl horses (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Bone Valley Formation of central Florida: Journal of Paleontology, 60, 466–475. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B.J., 1992, Fossil Horses. Systematics, paleobiology and evolution of the Family Equidae: Canada, Cambridge University Press, 369 p. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B.J., 1998, Equidae, in Janis, C. M., Scott, K. M., Jacobs, L. L. (eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America: USA, Cambridge University Press, 537–559. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B.J., 2006, Early Pliocene (latest Hemphillian) horses from the Yepómera local fauna, Chihuahua, Mexico, in Carranza–Castañeda, O., Lindsay, E.H. (eds.), Advances in Late Tertiary Vertebrate Paleontology in Mexico and the Great American Biotic Interchange: México, D. F., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología y Centro de Geociencias, 33–43. [ Links ]

MacFadden, B. J., Skinner, M. F., 1979, Diversification and biogeography of the genus Onohippidium and Hippidion (Mammalia: Equidae): Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 17, 199–218. [ Links ]

Marsh, O.C., 1874, Notice of new equine mammals from the Tertiary Formation: American Journal of Science, 7, 247–258. [ Links ]

McKenna, M.C., Bell, S.K., 1997, Classification of mammals above the species level: New York, USA, Columbia University Press, 631 p. [ Links ]

Miller, W.E., 1980, The Late Pliocene Las Tunas local fauna from southernmost Baja California, México: Journal of Paleontology, 54 (4), 762–805. [ Links ]

Miller, W.E., Carranza–Castañeda, O., 1984, Late Cenozoic mammals from central México: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4, 216–236. [ Links ]

Montellano–Ballesteros, M., 1997, New vertebrate locality of Hemphillian age in Teocaltiche, Jalisco, México: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 14, 84–90. [ Links ]

Olson, E.C., McGrew, P.O., 1941, Mammalian fauna from the Pliocene of Honduras: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 52, 1219–1244. [ Links ]

Osborn, H.F., 1918, Equidae of the Oligocene, Miocene and Pliocene of North America, iconographic type revision: Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, 2, 1–217. [ Links ]

Quinn, J.H., 1955, Miocene Equidae of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain: Bureau Economic Geology University of Texas Publications, 5516, 1–102. [ Links ]

Prado, J.L, Alberdi, M. T., 1996, A cladistic analysis of the horses of the tribe Equini: Paleontology, 39, 663–680. [ Links ]

Scott, E., 2004, Pliocene and Pleistocene horses from Porcupine Cave, in Barnosky, A. D. (ed.), Biodiversity response to climate change in the Middle Pleistocene: The Porcupine Cave fauna from Colorado: USA, University of California Press, 264–279. [ Links ]

Stirton, R.A., 1940, Phylogeny of North American Equidae: Buletin Department Geological Sciences, 25(4), 165–198. [ Links ]

Stirton, R.A., 1954, Late Miocene mammals from Oaxaca, Mexico: American Journal of Science, Series 4, 252, 634–638. [ Links ]

Tedford, R.H., Albright III, L.B., Barnosky, A.D., Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., Hunt, R.M., Storer, J.E., Swisher III, C.C., Voorhies, M.R., Webb, S.D., Whistler, D.P., 2004, Mammalian Biochronology of the Arikareean through Hemphillian interval (Late Oligocene through Early Pliocene Epochs), in Woodburne, M.O. (ed.), Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America: New York, USA, Columbia University Press, 169–231. [ Links ]

Webb, S.D., 1969, The Burge and Minnechaduza Clarendonian mammalian faunas of North–Central Nebraska: University of California Publications Geological Science, 78, 1–191. [ Links ]

Webb, S.D., Perrigo, S.C., 1984, Late Cenozoic vertebrates from Honduras and El Salvador: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4(2), 237–254. [ Links ]

Wilson, J.A., 1967, Additions to El Gramal local fauna, Miocene of Oaxaca, Mexico: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 30, 1–4. [ Links ]