Introduction

Airway evaluation through physical examination is unable to establish a strong positive predictive value for difficult tracheal intubation1, especially in the presence of non-documented clinical conditions, such as lingual tonsil hypertrophy (LTH). This condition is frequently associated with persistent sleep obstructive apnea in children after tonsillectomy1.

Lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue, and are a component of the Waldeyer ring; their inflammation and hypertrophy can easily be undetected through preoperative evaluation, and has been identified as a cause of unpredictable difficult ventilation and intubation2.

Clinical case

Male, 11 years old, 33 kilograms, suggested for excision of a recurrent cerebellum pilocytic astrocytoma. Previous history of atopy and prior surgeries, with a tonsillectomy at the age of two and excision of cerebellum tumor at the age of eight. In the last three months, developed sleep apnea with witnessed episodes (respiratory pauses and roncopathy), without dysphagia, dysphony or bleeding. No other medical issues were identified.

At preoperative evaluation of airway, the patient presented with Mallampati class I, good mouth opening, preserved cervical mobility and normal thyromental distance. On the right side of the floor of the mouth, a mass that looked like a hypertrophied tonsil could be seen. No history of difficult intubation. No other predictors of difficult airway were identified. After the American Society of Anesthesiology standard monitorization, and preoxygenation with O2 at 100%, an intravenous anesthetic induction was performed with 75 μg of fentanyl and 60 mg of propofol. As no difficulties with facemask ventilation were noticed, the muscular relaxant was administered (35 mg of rocuronium).

Direct laryngoscopy with a Mackintosh size two blade revealed only the proximal edge of the epiglottis (Cormack Lehane 3b), and a mass at the base of the tongue on the right side, with apparent posteroinferior extension causing the structures to deviate to the left side. Optimization maneuvers were attempted (laryngoscopy replacement, extension and compression of the neck) without success.

A new laryngoscopy showed active bleeding, limiting the visualization of surrounding structures. Two more intubation attempts with conduit use (frova®) were made, without success. Two different attending anesthesiologists attempted intubation with the same maneuvers, without success. A graduated anesthesiologist was called and attempted another intubation, with a Mackintosh size 3 blade, the aspiration of hematic secretions and utilization of a conduit (frova®). After three attempts, successful intubation was achieved with a number 6 aramed orotracheal tube (OTT) with cuff. Between the intubation attempts face mask ventilation was maintained with no difficulties. As control of bleeding at the base of the tongue was not achieved, OTT remained the primary goal.

After the intubation, OTT positioning was confirmed where we observed thoracic asymmetry with right chest depression and silence chest at pulmonary auscultation on the right side, as well as elevated pressure on the airway.

Lung recruitment maneuvers were performed with manual ventilation for two minutes, with normalization of airway pressures, return of thoracic symmetry and the presence of bilateral pulmonary auscultation, with scattered rhonchi predominant to the right side. To prevent the risk of airway edema, 100 mg of hydrocortisone were administered at this stage. Hemodynamic stability was present during the entire episode.

Presurgical preparation proceeded, with central venous catheterization in the right subclavian vein and arterial line placement in the right radial artery. After ventral decubitus positioning for surgical access, a sudden rise in airway pressure was noticed. Aspiration of the OTT revealed the presence of hematic secretions obstructing the airway. Instillation and aspiration of saline solution normalized the airway pressure. There was slight continuous bleeding from the oral cavity.

Due to the possibility of continuous bleeding in the inferior airway tree, no manipulation of the patient occurred while the rest of the material was prepped. After 10 minutes, a new episode of airway pressure elevation occurred, and was resolved in the same way as the previous one. Because the airway would not be accessible during the procedure, due to positioning, a decision to postpone the surgery was made. Observation by an otorhinolaringologist (ORL) was solicited, who described a hypertrophy at the root of the tongue, more exuberant on the right with active bleeding. Cauterization and tissue biopsy were performed.

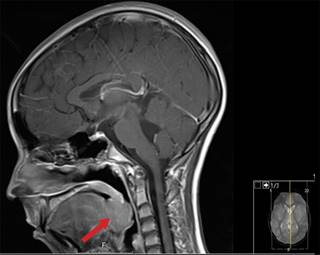

As there was a high airway risk and there a previous record of obstructive apnea, the patient was transferred intubated to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Nuclear magnetic resonance showed a lesion at the root of the tongue, adherent to the anterior face of the epiglottis and reaching the uvula and soft palate (Figure 1), which caused airway obstruction during relaxation of airway structures. Biopsy revealed normal tonsil tissue.

Figure 1: Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in sagittal plane from head and neck. Arrow-hypertrophied lingual tonsil.

The patient was later scheduled by ORL for a suspended laryngoscopy and possible lesion excision, however the excision wasn’t done due to the risk of tongue necrosis and the proximity of the lingual artery. One week after the beginning of the case, the patient was extubated without complications.

Discussion

LTH occurs mostly in an asymptomatic way. However, some cases can present with voice changes, snoring and sleep obstructive apnea3. About 2/3 of LTH patients underwent previous excision of palatine tonsils. Although it occurs mostly in adults with atopy, previous cases in children have been described3,4.

LTH can cause posterior mobilization of the epiglottis and become adherent to it, causing the cleavage plane between the posterior border of the tongue and the epiglottis to disappear, and making it impossible to insert the laryngoscope blade into the vallecula. Trauma to the hypertrophied tonsils can cause massive bleeding and airway edema, comprising patient ventilation and increasing the probability of prolonged intubation time in the postoperative period. The recommended approach for this patient includes the use of a straight laryngoscope blade inserted in the posterior face of the epiglottis and elevating both the epiglottis and the tongue as an only structure, causing minimal trauma and decreasing the chances of bleeding. In cases where LTH was previously diagnosed, the use of a fiberscope for intubation is recommended, with appropriate resources ready to be used in the event of airway bleeding4.

The definitive treatment of this condition is a tongue tonsillectomy, with massive uncontrollable bleeding of the tongue artery and necrosis of the tongue being two of the most serious complications; however, successful excisions have been described5.

Conclusion

We described a case of an unpredictable difficult airway in a child with LTH with no previous diagnosis. LTH is still under-diagnosed and identified as a risk factor for difficult airway and all the complications associated with it. In these situations, knowledge of the guidelines on how to approach both predictable and unpredictable difficult airway is important for favorable outcomes, as is the knowledge of different clinical cases such as this one, whose specificities aren’t outlined in any guidelines.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)