Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Problemas del desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 0301-7036

Prob. Des vol.38 no.150 Ciudad de México jul./sep. 2007

Artículos

The entry of foreign banks into latin America: a source of stability or financial fragility?

Alexandre Minda*

* Associate Professor in Economics at the Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Toulouse (France) and researcher at The Institute of Studies and Research into the Economy, Politics and Social Systems (LEREPS), University of Toulouse 1 Social Sciences, France. E-mail: alexandre.minda@univ-tlsel.fr

Fecha de recepción: 1 de mayo de 2007.

Fecha de aceptación: 2 de agosto de 2007.

Abstract

This paper aims to contribute to the debate on the presence of foreign banks in Latin America. To clarify the discussion, we shall conduct a survey of the empirical literature devoted to internationalization in the banking sector so as to provide a better analysis of the determinants that currently underpin foreign banking investments. The multinational banks concerned come mainly from the European Union, particularly Spain, and primarily focus their investments in the region's large emerging economies. They display profitability indicators that are on a par with those of domestic banks, generate a significantly lower level of operational efficiency, but are more efficient in their management of risk. International banks can help reinforce banking stability by spreading new risk management methods, introducing new control procedures and strengthening asset solidity. However, they are partly responsible for the credit squeeze from which Latin America is suffering. Foreign banks can be the cause of new sources of banking fragility such as the exposure to foreign exchange risks, the increase in market influence, persistently high intermediation spreads and moral hazard.

Key words: foreign banks, Latin America, financial stability, credit squeeze, banking fragility.

Resumen

Este documento pretende contribuir al debate sobre los bancos extranjeros en América Latina. Para aclarar esta discusión, examinamos la literatura empírica dedicada a la internacionalización del sector bancario para proporcionar un mejor análisis de las determinantes que sostienen inversiones de actividades bancarias extranjeras. Los bancos multinacionales en cuestión son principalmente de la Unión Europea, España, enfocados a las economías emergentes más grandes de la región. Éstos exhiben indicadores de rendimiento iguales que los bancos domésticos, generando un perceptible nivel bajo de eficiencia operacional, pero mejor en su manejo de riesgos. Los bancos internacionales pueden ayudar a reforzar las actividades bancarias con métodos de manejo de riesgo, nuevos procedimientos de control y al consolidar la solidez del activo. Sin embargo, son en parte responsables del estrechamiento del crédito que sufre América Latina. Los bancos extranjeros pueden ser la causa de nuevas fuentes de fragilidad de las actividades bancarias, tal como la exposición a los riesgos de la moneda extranjera, el incremento de la influencia del mercado, persistiendo en la alta intermediación de las operaciones y su abuso de confianza.

Palabras clave: Banca extranjera, fragilidad bancaria latinoamericana, estabilidad financiera.

Résumé

Cet article vise à nourrir le débat sur laprésence des banques étrangères en Amérique latine. Nous effectuons un survey de la littérature empirique consacrée à la multinationalisation bancaire afin de mieux analyser les déterminants actuels des investissements bancaires étrangers. Les banques étrangères possèdent des indicateurs de rentabilité comparables aux banques locales, dégagent une eficacité opérationnelle sensiblement inférieure mais sont plus efficaces dans la gestion de leur risque. Ellespeuvent améliorer la stabilité bancaire par la diffusion de nouveaux modes de gestion des risques, l'introduction de nouvelles procédures de contrôle et le renforcement de la solidité patrimoniale. Cependant, elles peuvent être à l'origine de nouvelles sources de fragilité bancaire comme la restriction du crédit, l'exposition au risque de change, le maintien des marges d'intermédiation à un niveau élevé et l'aléa moral.

Mots clés: Banques étrangères, Amérique latine, stabilité financière, restriction du crédit, fragilité bancaire.

Resumo

Este documento pretende contribuir no debate da presença dos bancos estrangeiros na América Latina. Para esclarecer esta discussão, levamos a cabo um exame da literatura empírica dedicada à internacionalização do setor bancáriopara proporcionar uma melhor análise das determinantes que sustentam na atualidade inversões de atividades bancárias estrangeiras. Os bancos multinacionais em questão são principalmente da União Européia, em particular da Espanha, enfocados às economias emergentes de maior tamanho da região. Estes exibem indicadores de rendimiento iguais aos dos bancos domésticos, o que gera umperceptível nivel baixo de eficiência operacional, mas mais eficiência em seu manejo de riscos. Os bancos internacionais podem ajudar a reforçar as atividades bancárias com métodos de manejo de risco, novos procedimentos de controle, bem como a solidez do ativo. No entanto, estes são em parte responsáveis pelo estreitamento do crédito que padece a América Latina. Os bancos estrangeiros podem ser a causa de novasfontes de fragilidade das atividades bancárias, tal como a exposição aos riscos da moeda estrangeira, o incremento da influencia do mercado, persistindo na alta intermediação das operações e seu abuso de confiança

Palavras chave: Banco Estrangeiro, Fragilidade Bancária, América Latina, Estabilidade Financeira, Estreitamento do crédito.

Introduction

The presence of foreign banks in Latin American is not something new, dating back to the period that preceded the first phase of globalization at the end of the 19th Century. The first to arrive were the Europeans, notably the British, in the early 1860s. The process started with the London and River Plate Bank and the London and Brazilian Bank in 1862, followed a year later by the British Bank of South America, English Bank of Rio de Janeiro and London Bank of Mexico and South America. The prime objective of these banks was to finance Europe's and the United States' flourishing trade with Latin America. Bank financing was equally directed towards the export of primary products as the import of manufactured goods from the increasingly industrialized countries. Foreign banks were therefore able to help Latin American countries gain a foothold in the world economy, while at the same time maintaining them in the role of producers and exporters of primary products within the international division of labor which was taking hold at that time.

This somewhat ambiguous role played by foreign banks at the end of the 19th Century is still prevalent today. The second phase of the globalization process that we are currently experiencing has actually been accompanied by a vast process of financial liberalization which has helped to drive the rapid development of foreign banks in the emerging economies, especially in Latin America since the mid 1990s. Foreign banks now control almost 30% of the region's bank assets, with the figure exceeding 80% in the case of Mexico. Local currency loans granted by these foreign banks' subsidiaries and branches represent more than 65% of total lending.

This massive entry of foreign financial institutions into Latin America prompts a number of questions. What is the explanation for this craze in the Latin American markets? Does their attractiveness lie solely in the economic and institutional changes that are at work in these countries? Maybe one can also detect here the consequences of the banking sector restructurings that are taking place in developed countries? Likewise, it is worth homing in on the origins of the banks that are investing in Latin America to see whether they are rolling out identical or different strategies in relation to the subcontinent. Furthermore, such an influx of foreign banking investors is not without repercussions on the Latin American banking systems. Is it contributing to a better allocation of resources between the various economic players? Is it working to the benefit of financial stability or is it generating new risks?

To answer these questions, we shall first identify the reasons behind the expansion of foreign banks in Latin America. We shall start by conducting a survey of the empirical literature devoted to the subject of bank internationalization. This will enable us to gain a better understanding of the current determinants behind foreign banking investments. Secondly, we shall examine empirically the recent expansion of foreign banks in Latin America. At that point we shall focus both on the origin and the geographical destination of their investments, at the same time highlighting their growing influence in the subcontinent's banking systems. After those two stages, we shall study the impact of the entry of foreign banks from the angle of microeconomic efficiency and macroeconomic effectiveness. The accent will be put on their influence in terms of profitability, liquidity and efficiency together with their contribution towards financial stability. We shall conclude our review by analyzing the risks generated by the presence of foreign financial institutions, concentrating on their role in relation to the credit squeeze and banking fragility.

Reasons for the expansion of multinational banks in Latin America

An analysis of the explanation behind the expansion of foreign banks in Latin America will be presented in two stages. First, we shall conduct a rapid survey of the empirical literature devoted to the determinants in banking investments abroad. We shall then check the validity of this empirical work in the context of Latin America.

The contribution of empirical literature

García Herrero and Navia Simón (2003), in a survey1 of the empirical literature, highlight three main determinants for the expansion of foreign banks (see figure 1). First, macroeconomic factors in the home country can strengthen bank internationalization. This can prompt the question of the correlation between foreign direct investments (FDI) and economic cycles. Garcia Herrero and Navia Simón reveal a lack of consensus among authors and regret the absence of meaningful research into the influence of economic cycles on bank investments abroad. Likewise, fluctuating exchange rates have a direct bearing on investment decisions at an international level, but there too the authors who have investigated this area fail to agree on the consequences of currency appreciations or depreciations on foreign investment. On the other hand, there is a broad consensus that high real interest rates do hinder FDI flows. Calvo et al. (2001) stress that the FDI in developing countries slows down when there is a hardening of U.S. monetary policy. Conversely, Guillén and Tschoegl (1999) show that Spanish banks increase their investments abroad as soon as domestic interest rates are relaxed. In the case in point, they try to offset the low domestic intermediation spreads by seeking higher spreads in the emerging economies.

A larger number of publications have dealt with the macroeconomic factors in the host country. Focarelli and Pozzolo (2001) state that international banks take into account the economic growth prospects of the country likely to host a new subsidiary. The authors also indicate that foreign banks prefer investing in countries where the financial system is relatively developed yet sparsely concentrated. On the other hand, economic instability tends to discourage foreign investors.

Institutional factors also have to be taken into consideration. Hence, national regulations that are restrictive towards certain banking operations will only serve to encourage financial institutions to leave their home territory. This will be all the more tempting if at the same time the host countries implement measures, particularly fiscal, to attract them (Barth et al., 2003). Banks may also be drawn towards countries where modern systems of jurisdiction have fostered creditor protection rights and bankruptcy procedures. In addition to low taxation levels, Claessens et al. (2001) point out that banks are also attracted by countries where per capita income is increasing rapidly.

The third set of factors concerns microeconomic behavior patterns. The most frequently tested hypothesis among competitive advantages concerns the banks' decision to follow their customers. Several authors note a positive correlation between international trade flows and FDI and banks' foreign investments. Focarelli and Pozzolo (2001) confirm this correlation for all the OECD countries. Gruble (1977) shows that awareness of customer needs in their home country generates a competitive advantage and banks accompany their customers abroad to prevent local banks gaining access to that information. On the other hand, research providing evidence to support the correlation between real flows and banking flows is still in the embryonic stage. As García Herrero and Navia Simón (2003) underline, the amount of FDI targeting in these countries can be restricted if the provision of financial services is insufficient. Therefore, the entry of foreign banks can be considered as a prerequisite for future FDI and not as the consequence of having followed their customers into external markets.

Among the other competitive advantages, a common origin between the host and home country is recognized by several authors as playing an important role in the decision to invest abroad. Galindo et al. (2003) show that colonial links, cultural proximity and speaking the same language, influence the geographical destination of investments. As regards efficiency, bank size and the standing of the host country and its financial system are also deemed to be variables that have to be taken into account. Potential economies of scale, whether its international activity began recently, or even the possibility of using a joint distribution network are additional reasons in favor of starting to conquer overseas markets.

Bank investments abroad also provide the opportunity to acquire greater risk diversification. Admittedly the process will create new risks, (cf the Latin American risk for Spanish banks) but at the same time they help to provide a better geographical spread of global risks. As Jeffers and Pastré (2005) point out, they also offer the opportunity of finding new revenue sources, and hence a lower degree of dependence on the domestic market. The last determinant mentioned in the empirical literature concerns the strategic reaction. Financial globalization and the oligopolistic structure of banking markets actually lead banks into wanting to maintain or enlarge their market shares on a worldwide scale. This search for a critical size has mainly been pursued by restructurings in the form of domestic mergers and acquisitions. Despite the geographical distances, cultural inertia, regulatory constraints and differences in supervisory structures, recent examples at a European level2 would indicate that future restructurings could also take place on a cross-border basis (Plihon et al., 2006).

Determinants of the recent entry of foreign banks into Latin America

As the survey suggests, macroeconomic factors have played a key role in the recent inflow of foreign banks into Latin America, particularly regarding the transformations that countries in the region have undergone since the beginning of the 1980s. After the "lost decade" period of the 1980s, marked by a decline in living standing in several economies, the 1990s saw the region implement, under the influence of international financial agencies, adjustment policies that led to higher growth rates (table 1). Admittedly, the growth rates are less sustained and less homogenous than in Asia, but they come in marked contrast to the earlier period. The first three years of the new century brought a renewed upturn in growth, still below the Asian level but ahead of that recorded in the other regions of the world.

This macroeconomic performance has attracted foreign investors, all the more so in that it has been accompanied by a sharp drop in inflation. From an annualized rate of 162.8% between 1988 and 1997, price increases have now actually fallen below the symbolic 10% mark, since the year 2000. This massive disinflation has encouraged a greater degree of confidence in monetary and financial assets. At the same time, the current account balance, which was running a substantial deficit during the 1990s, showed a surplus in 2005. This improvement in "macroeconomic fundamentals" and the significant rise in per capita GDP (+9% between 1995 and 2005) have broadened Latin America's market prospects despite the fact that the structural adjustments have created disparities within the population3. Furthermore, demographic dynamism has materialized with young people representing a higher proportion of the population (1/3 of the population is aged under 15) hence making it an attractive market for the retail banking sector. Even if young people are displaying a negative savings rate, banks are looking to the longer-term loyalty from this customer sector with the aim of offering a wider range of banking and financial products and services in the future (property loans, consumer credit, bank card, life insurance ...).

Another reason for the entry of foreign banks was the structural problems faced by the domestic banks. Moguillansky et al. (2004) cite the series of handicaps the Latin American banking systems were suffering: the low lending/ GDP ratio, the preponderance of short-term loans, high private financing rates, and the impossibility for the majority of households and companies to gain access to credit. To improve the efficiency of the banking industry, governments started to institute substantial liberalization measures leading to the so-called "first-generation" financial reforms (table 2). These are materialized by the liberalization of interest rates, the lowering of entry barriers, a wave of privatization and a financial opening to the exterior. This deregulation was accompanied by a huge growth of lending with its stream of non-performing loans, but also the financing of speculative investments on the property and stock markets (Minda, 2003).

The banking crises which followed this financial liberalization (Mexico in 1994-1995, Brazil in 1999, Argentina in 2001) paved the way for second-generation reforms characterized particularly by the enhancement of bank supervisory mechanisms (cf the adoption of minimum capital requirements in accordance with the Basel 1 Accord). In addition to their local repercussions, the reforms of the financial system encouraged the entry of foreign banks. This was facilitated by deregulation measures which opened up new areas of banking activity (leasing, stock market operations, bancassurance, pension fund management), but also sparked the spate of mergers and acquisitions that ensued in the wake of the banking crises and in which the international banks were to play an active role (Correa, 2004).

Not only did the privatization of banks play a major contribution in the entry of foreign banks, it also influenced the privatization trend among other public sector companies. Of the 500 largest Latin American corporations, 93 were publicly controlled during the period 1990-1992 compared with only 40 in 1998 (CEPAL, 2000). In addition to the internal liberalization and external opening encouraged by the international organizations, the privatizations also aimed to establish public sector finances on a healthier footing (Hawkins and Mihaljek, 2001). This foreign influx was facilitated by the low valuation of Latin American corporations, including the banks, compared to corporations from developed countries. Sebastian and Hernansanz (2000) illustrate how, at the end of the 1990s, it was ten times cheaper to acquire 1% of the banking deposit market in Argentina or Mexico compared with the cost of the same proportion in Germany.

International banks also increased their presence in Lain America so as to follow the international expansion of their existing clients (Correa and Vidal, 2006). Between 1990 and 1997 the region absorbed an average of almost 37% of the net flow of private capital directed at emerging economies (table 3). Over the same period it was the number one host region for portfolio investments realized in emerging markets with 62% of the total and the second region in terms of FDI (31%). From 1998 to 2002, it even secured the top position in attracting nearly 47% of private capital inflows, of which 37% were in the form of FDI, compared with 34.7% for Asia and 13.8% for Central and Eastern Europe. Even if Latin America's relative share has since decreased, this massive entry of foreign investors during the nineties, particularly multinational companies, provided the incentive for banks from developed countries to accompany them, and in some cases even to arrive before them, so as to satisfy multinational companies' requirements for financial products and services. International banks were better equipped than the domestic banks to meet multinational company needs for foreign currency loans, international issues, clearing techniques, exchange risk management or even in terms of advice on mergers-acquisitions and preliminary help for their set-up abroad.

Furthermore, during the 1990s the Latin American banking system presented profit opportunities for foreign establishments. Intermediation spreads were much higher than those generated in developed countries. The average spread on loans was 5.76% between 1988 and 1995 compared with 2.8% for OECD member countries. (Claessens et al., 2001). At the same time, another problem confronting Latin American banks was their inefficiency. Their operating costs were significantly higher than those observed in other emerging markets. Moguillansky et al. (2004) attribute their lack of efficiency to the high level of inflation undergone during the 1980s which enabled banks to have high spreads and not to pay too much attention to their cost base.

The expansion of foreign banks in Latin America

To analyze the recent expansion of multinational banks in Latin America, we shall start by examining the dominant position occupied by the subcontinent within the emerging economies. This will then enable us to measure the growing weight of multinational banks within the Latin American banking industry as well as highlighting the role played by European, and notably spanish, banks.

The rapid development of multinational banks in the emerging economies

FDI in the financial sector of the emerging markets experienced a period of rapid growth from the mid 1990s. As we shall see, Latin America ranks highly in the strategy of international banks. The value of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the banking sector of emerging countries jumped from 2.5 billion dollars between 1991 and 1995 to 51.5 billion dollars for the period 1996-2000, and to 67.5 billion dollars from 2001 to October 2005 (Domanski, 2005). The proportion of mergers and acquisitions targeting banks in emerging economies moved up from 13% of the world total over the period 1991-1995 to 35% from 2001 to October 2005. In the first three years of this century, more than a third of all cross-border mergers and acquisitions have taken place in the emerging economies. Latin America figured as a prime choice for these bank restructuring operations, accounting for 48% of cross-border merger and acquisition flows towards the emerging world between 1991 and October 2005, compared to 36% for Asia and 17% for Central and Eastern European countries. Albeit over a shorter period, Focarelli (2003) obtains similar results, giving Latin America a 52.9% share between 1999 and 2002 against 24.1% for Asia, 15.5% for East European countries and 7.6% for Africa and the Middle East.

This acceleration in restructurings brought with it greater participation by foreign establishments in the emerging banking systems. While the proportion of foreign bank holdings in the total bank sector assets of emerging economies does not exceed 10% in Asia, the figure is as high as 40% and 60% respectively in Latin America and in the countries of Eastern Europe in 2005 (table 4).

From one region to another, there are some well-known differences. The increase in foreign ownership was particularly rapid in Eastern Europe, where the share of banking assets under foreign control increased from 25 percent in 1995 to 58 percent in 2005. The entry of foreign banks into Eastern Europe started to accelerate in the mid-nineties in the wake of privatization programs and applications by East European countries to join the European Union. It was particularly the Czech Republic and Poland that benefited from the entry of foreign establishments. In Latin America, the share of banking assets under foreign control increased from 18 percent in 1995 to 38 percent in 2005. In contrast, internationalization of banking has proceeded more slowly in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The presence of foreign banks in Asia is still relatively low-key, even though some recent domestic bank acquisitions have been concluded and some holdings acquired, for example in China, India and South Korea4. As Domanski points out (2005), the re-capitalization of insolvent banks in Asia has tended to be carried out more with local investments, such as state-controlled asset management companies whose aim is to solve unproductive loan issues.

The growing importance of foreign banks in the banking industry

It was immediately after the 1994 Mexican crisis that foreign banks started to accelerate their penetration of the Latin American market, favoring a presence in the form of subsidiaries at the expense of branches and minority holdings. In many cases the establishment of subsidiaries paved the way for the acquisition of existing local banks. The creation of subsidiaries by acquiring domestic banks gives the parent company numerous advantages: the existence of a network with its inherent infrastructures, the ability to retain a centralized decision-making process, flexibility of commercial strategies, the transfer of its brand name and image.

The massive entry of foreign banks has led to an increase in their share of total bank assets in Latin American countries. Still relatively diminutive in 1990, the percentage moved up rapidly from 1994 onwards. The increase in foreign bank participation was especially noteworthy in Mexico. In this country, foreign institutions accounted for 82% of total bank assets in 2004 compared with only 2% in 1990, for an amount equal to half the country's GDP (table 5). The increase in foreign ownership was particularly rapid in Argentina, where the share of banking assets under foreign control increased from 18 percent in 1994 to 49 percent in 2004. In, Chile, Peru and Venezuela the proportions range between 30% and 50%.

Spanish banks: prime movers in conquering Latin American markets?

Domanski (2005) distinguishes three categories of foreign investors operating in the emerging economies, particularly in Latin America. The first comprises the all-purpose banks such as Citigroup who have been implementing "one-stop shopping" strategies, aiming to provide a complete range of banking and financial services throughout their whole global network. Citigroup, born in 1998 from the merger of Citibank and Travelers, is therefore very present in Latin America, also in pension-fund management. Citigroup's acquisition of Banamex, the number two Mexican bank, for $12.5 billion in 2002, represents the largest foreign investment transaction to date realized in Latin America. The second group consists of the commercial banks which have relatively saturated home markets and which are focusing their strategy on an emerging region with the aim of realizing economies of scale and product offer. In Latin America, this is notably the case of the European banks which account for more than 60% of the financial sector's FDI, with the Spanish banks heading the pack. The last category involves non-bank investors such as finance companies which deal in consumer credit and capital investment funds whose prime objective is acquiring and restructuring credit institutions.

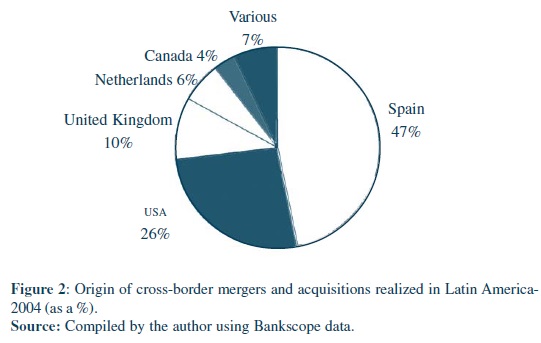

The geographical origin of foreign investors points to a clear domination of European banks. On the basis of the cross-border mergers and acquisitions recorded in Latin America in 2004, nearly two-thirds were realized by European banks (figure 2). The relatively low presence of the United States (26% of acquisitions in 2004) can be explained by several reasons. First, throughout the whole of the 1990s American banks underwent a huge consolidation process5 which ate into a large part of their resources (CEPAL, 2003). Secondly, these banks concentrated more on developed countries, particularly the European Union whose markets were better suited to their all-purpose bank strategies. Furthermore, the European financial systems were also undergoing substantial reform which potentially opened up opportunities for the American banks. Lastly, the debt crisis of the 1980s had exposed the American banks more acutely, hence explaining their more marked risk-aversion stance towards Latin America.

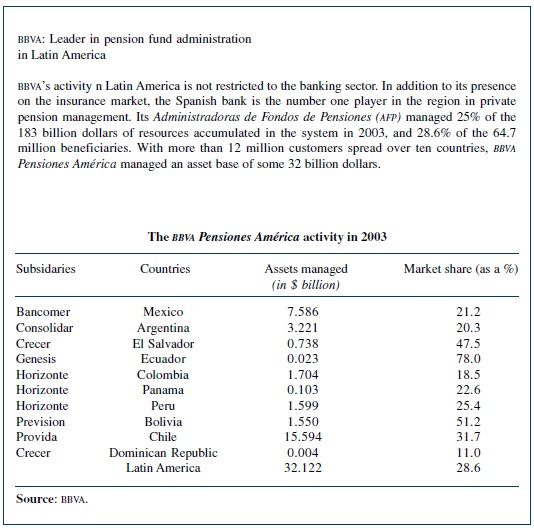

It was the Spanish banks meanwhile that took advantage of the 1990s to penetrate the region massively. In 2004, almost half the finance sector's FDI was realized by operations involving Spanish institutions (figure 4). There are several reasons for the attraction of Spanish banks to Latin America: accompanying the increase in Spanish companies' FDI from 1997, the reduction of interest rates in Europe, the aging of the Spanish population, the high level of profitability attained by Spanish banks, saturation of the Spanish market, the difficulty of obtaining increased market share within Europe, and cultural proximity (Calderón and Casilda, 2000). The principal players in the conquest of the Latin American market were SCH, which favored direct 100% acquisitions and BBVA which preferred to establish its presence by taking majority holdings. SCH was born in 2000 from the merger of Banco Santander with Banco Central Hispano. BBVA was the result of the merger in 1999 between Banco Bilbao Vizcaya and Argentaria. It only took a few years for these two groups, which together represent more than 30% of the balance sheet totals of Spanish credit institutions, to occupy the leading positions on the Latin American market as regards retail banking, pension fund management (cf. insert 1), bancassurance, and investment banking activities. Latin America constitutes an important part of the bank's net profit structure by region (47 % for BBVA and 34 % for Santander in 2005, table 6).

Foreign banks: a source of microeconomic efficiency and banking stability?

For all that, has the entry of foreign banks into Latin America contributed to increased stability within the Latin American banking industry? In order to answer this question, we shall look at the impact of international banks on microeconomic efficiency, basing our analysis on such indicators as profitability, efficiency and liquidity. The contribution of foreign banks to greater economic effectiveness will be studied by examining their role particularly as regards product and services engineering, risk management and financial profitability.

The impact of foreign banks on microeconomic efficiency

The indicators used to measure microeconomic impact are similar from one study to another. Moguillansky et al. (2004) isolate three indicators in order to compare local and foreign banks (profitability, efficiency and liquidity), basing their review on the data available for the 20 largest institutions present in the seven largest countries which make up 80% of the Latin American banking system. Moguillansky et al conclude that between 1997 and 2001 there are no significant differences in profitability, as measured by the return on assets (ROA) and the return on equity (ROE), between local banks and foreign banks (table 7). Over that period, the return on assets coefficient is significantly higher for the national banks. The return on capital ratio is higher for foreign banks in Argentina, Mexico and Venezuela. In 2004, the ROA is barely higher in local banks, except for Venezuela. In the same year, the roe is higher in the national banks for Brazil and Chile but negative for foreign banks in Argentina because of economic crisis (1999-2002).

In terms of efficiency, the ratio between operating expenses and total income clearly favored local banks between 1997 and 2001. Only Chilean and Mexican banks have a higher operating ratio than foreign banks. It can be seen that this ratio falls substantially in both types of bank between 1997 and 2001. As Moguillansky et al. underline, this improvement in operational efficiency is linked to the development of rationalization processes in bank operations, the optimization of human resources and the introduction of new technologies, including multimedia platforms.

On the other hand, risk management as measured by the ratio of overdue loans to gross loans appears to be more tightly controlled by foreign banks as they display significantly better results in all countries. Is this because of a more selective loan policy towards some customer sectors? It can be seen that the percentage of non-performing loans increased between 1997 and 2001 for foreign and local banks alike. The increasing number of households and corporate customers unable to honor their commitments is partly due to the consequences of economic crises that have taken place, particularly in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina during this period.

The indicator of liquidity as measured by the ratio of total loans net of provisions for non-performing loans to total deposits varies considerably from one country and from one type of bank to another. In Brazil and Colombia, foreign banks are more liquid than local banks, while it is the opposite in Chile and Mexico where the liquidity ratio was higher in local banks between 1997 and 2001. However, this indicator of liquidity is more homogenous in local banks (a spread of 61 points between Brazil and Mexico in 2001) whereas there is a much greater deviation in foreign banks (a spread of 164 points between Mexico and Colombia). Foreign banks appear to adopt different stances in different countries, a fact which would indicate differing risk evaluation scenarios.

These results partially corroborate other studies that have been conducted on the impact of foreign banks in the emerging economies. Claessens et al. (2001) find that, as a general rule, foreign banks have broader interest rate spreads and higher profitability than local banks. Levine (2001) notes that foreign banks encourage competition, thereby enhancing local bank efficiency. Among other studies focusing on Latin America, Crystal et al. (2001) show that foreign institutions have experienced higher growth rates for their lending and react more aggressively in the face of non-performing loans. On the other hand, Levy-Yeyati and Micco (2003) observe that foreign banks are confronted by high insolvency risks as a result of high gearing and greater fluctuations in income.

Foreign banks and macroeconomic effectiveness

Several empirical studies tend to prove that foreign banks help to improve the functioning of the local banking markets. Claessens et al. (2001) show that international banks increase the degree of competition between institutions, introduce new financial products and services and possess better risk management techniques. Crystal et al., (2001) stress the fact that foreign bank loans are less volatile compared to local banks and that their lending significantly increases during times of crisis.

It would also appear that foreign banks generate greater macroeconomic effectiveness due to their dissemination of new risk-management approaches and new control and corporate governance procedures throughout the rest of the banking sector. As Calderón and Casilda (2000) underline, they had a stabilizing and deepening effect on the financial sector, particularly due to the role they played in developing wider and more professionalized inter-bank markets. They also played a by-no-means insignificant role in restoring and strengthening the solidity of the asset base within the banking system. Local customers tended to have greater confidence in financial institutions which had an international standing. Evidence of this confidence can be seen in the "flight to quality", failing which customer deposits would have left the country.6

But did the entry of foreign banks actually reinforce the stability of Latin American banking systems? Moguillansky et al. (2004) put forward three factors which could have engendered this virtuous relationship. First, international banks used their more sophisticated risk-management techniques, based on more rigorous supervision by the authorities in their countries of origin. Given their wider international risk diversification, as shown by their presence on the other continents, this would make them less vulnerable to the region's domestic cycles. The parent companies could always act as a lender of last resort if their subsidiaries encountered liquidity problems.

Table 9 shows that economic profitability measured by roa, and financial profitability, measured by roe, improved substantially in Latin America between 2001 and 2005. It is clear that improvements in profitability encourage banking stability. To begin with it means that risks can be better covered by constituting reserves and provisions. It also means an increase in equity which represents an additional security to lessen the impact of any potential economic crises. At the same time, the use and dissemination by foreign banks of more sophisticated risk-management techniques also contributed to greater financial stability. Table 9 shows that the proportion of non-performing loans in relation to total lending decreased substantially between 2001 and 2005, including in those countries which have a high concentration of foreign institutions, such as Mexico, Chile, Argentina and Peru. This improvement in managing counter-party risk contrasts with the period 1997-2001 when non-performing loans as a proportion of total lending had increased for both local and international banks alike (table 8). The best credit risk-management is the fruit of a narrower segmentation of target customers, resorting to scoring techniques which restrict the amount of loan commitments to those customers who score less well, and the use of financial instruments such as credit derivatives and debt securitization. However, the increase in the provisions for non-performing loans in all countries, except for Brazil, between 2001 and 2005 visibly proves that continuing efforts are required to better select and control risks.

Risks created by the entry of foreign banks into Latin America

Even if foreign banks can, under certain conditions, contribute to greater financial stability, does not their growing importance at the same time create new risks? As we shall observe, their entry has not solved the restriction of credit from which Latin America is suffering. In some instances it may actually have provoked new sources of fragility.

Foreign banks and the restriction of credit to the private sector

The banking system plays a key role in the mobilization and spread of capital in emerging countries, where it is even more involved in financial intermediation than it is in developed countries. Intermediating funds, transforming short-term into long-term financing, facilitating payment flows, managing liquidity, granting loans, maintaining financial discipline among borrowers -all of these banking functions are essential for the correct functioning of the real economy. In Latin America, capital markets have developed to different degrees, where banks are the only institutions capable of supplying suitable information in order to produce positive externalities.

Indeed, as Peltier (2005) underlines, Latin America is suffering from a major shortage of credit, so much so that the pace of growth is being curbed, hindering economic development. Financial liberalization, structural reforms and the inflow of foreign capital brought with them a significant rise in domestic borrowing in the early nineties. In the case of Mexico, de Luna Martínez (2002) notes that between 1991 and 1994 bank loans increased at eight times the rate of real growth of GDP. During that period, portfolio investments attracted by the high yields, provided credit institutions with substantial resources. The emerging countries which were the major beneficiaries of private capital flows are also those whose banking sectors experienced the most rapid expansion. But the speed of this expansion means that the banks had difficulties in identifying the good borrowers from the bad, because when economic growth is buoyant, a lot of borrowers give the impression of being a profitable and liquid investment, but these characteristics are merely temporary (Minda and Truquin, 2005). The turn-rounds in the economic climate together with major price fluctuations on the financial markets make these borrowers insolvent and depreciate the value of collateral assets. Hence, the banking crises which followed one another from 1994 onwards prompted a slowdown in the expansion of credit.

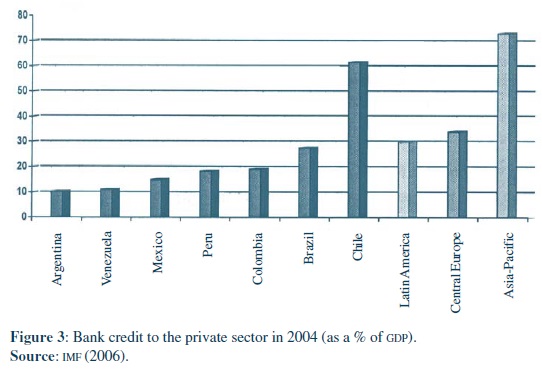

Figure 3 shows how Latin America is suffering from a credit shortage compared with other emerging economies. Lending to the private sector represented only 30% of GDP in 2004 against 34% in Central Europe and 73% in the Asia-Pacific region. Even if Chile and Brazil appear to be less affected by this credit standstill, private companies and households in the other countries mentioned are victims of a shortage of financing. This situation is all the more critical in that the relative rarity of credit has made the cost of financing extremely expensive. Lending rates and bank intermediation spreads are significantly higher than those encountered in other emerging nations. There are, however, some notable differences within the region itself. The countries which have the lowest real rates are those that succeed in obtaining the soundest macroeconomic fundamentals (modest levels of public debt, low inflation, current deficit contained) and/or that possess more efficient banking sectors and/or have the least systemic credit risks (Peltier, 2005). Such is the case of Mexico, where in 2004 the real lending rate was 2.5%, and Chile where it was 4.0%. Conversely, the highest lending rates were to be found in countries where the fundamentals are the most fragile (high public debt, persistent inflation), and/or where banks have the highest operating costs and/or the high credit risks are the result of an unstable macrofinancial environment. Brazil and Peru, where in 2004 average real lending rates were as high as 48.5% and 10.8% respectively, come into this category.

There are several reasons for this volume and cost-driven restriction of credit. The structural weakness of savings rates7 penalizes bank resources. This deficiency comes from the low rate of household savings, which in turn has several causes: disparities in income and wealth, distrust of the currency, reminiscent of the periods of hyperinflation, the young population, the low level of banking services available, and a very narrow middle-class category. In addition, issues of government securities to finance internal and external debt servicing absorbed part of the loanable capital, taking it away from investment in private sector driven projects, as well as helping to push interest rates up (Salama, 2006b).

Are foreign banks partly responsible for the credit restriction which is penalizing Latin America? From this point of view, the experience of Mexico, which is the country with the largest number of foreign banks, is particularly telling. Table 10 shows that the market share held by foreign banks jumped from 11% to 83% between 1997 and 2004. Whereas, over the same period, bank lending to companies and households decreased by more than 8%. Bank lending to the private sector, which still represented 25% of GDP in 1997, only represented 14% in 2004. Haber and Musacchio (2005) show that the fall in lending was mainly due to the consequences of the 1994-1995 crisis which weakened bank balance sheets, as they began to adopt a more rigorous stance towards risk management. The very large proportion of total banking assets held by foreign banks inevitably leads us to conclude that they had a role to play in the restriction of credit. Initially they did contribute to bank recapitalization by subscribing to State-issued bonds in order to discharge the banking sector's non-performing loans. This subscription to risk-free, high yielding investments contributed in part to the improvement in bank profitability. As soon as government bond yields began to decline, the foreign banks, which in the interim had acquired local banks, preferred to raise their charges rather than increasing their loan exposure to households and companies in order to maintain their profitability.

Foreign banks and the fragility of local banking systems

The expansion of foreign banks in Latin America has prompted numerous criticisms, the most virulent being those regarding their role in undermining the banking systems. They are accused of positioning themselves in the most profitable markets or segments, particularly the large corporations and the upmarket household sectors. In so doing, they were responsible for the lower profitability levels incurred by local banks which had to manage a higher risk customer portfolio (Gnos and Rochon, 2004; Weller, 2001). Likewise, compared to large corporations, it became increasingly difficult for small and medium-sized companies to raise financing from foreign financial institutions, the largest of which base their lending on a standardized, global risk-management approach. Certainly, these banks increasingly make use of decision-making aids such as scoring and expert systems in order to reduce the cost of risk treatment and to increase the security of operations.

A study covering Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Peru, Clark et al. (2003) emphasizes how small foreign banks lend less to small companies than the small local banks do. Meanwhile the same authors note that in Chile and Colombia, large foreign banks lend more to small companies than the large local banks do. In Argentina and Chile, they observe that the amount of lending to small companies by large foreign banks is increasing at a faster rate than lending by similar sized national banks.

Furthermore, the major part of foreign banks' assets devoted to public sector financing requirements, together with the strong dollarization of their balance sheets, give them considerable exposure to sovereign and foreign exchange risks8. Peltier (2005) states that the average level of dollarization in Latin America stood at 37% of deposits in 2003 compared with 25% in 1991 and at 40% for loans. In order to protect themselves against exchange risks and to reduce their foreign currency positions, the banks lend in dollars by drawing on dollar deposits, including lending to companies that are not outward-facing. They are all the more willing to do this insofar as borrowers prefer foreign currency loan commitments because they attract lower interest rates than local currency lending. The only drawback is the fact that the banks transfer part of their foreign exchange risk exposure to non-financial agents, thereby increasing their credit risks, as the financial health of their borrowers is jeopardized. In addition, in the event of a currency depreciation, those banks which have highly dollarized balance sheets are exposed to risks of insolvency caused by an increase in default rates, as well as to risks of illiquidity resulting from a rush on deposits in the event of a panic movement as could be provoked by some external crisis (Correa, 2006).

Similarly, cross-border acquisitions realized by large international banking groups have encouraged the concentration of local banking networks. Mexico, for example, has been the scene of several large-scale operations. In 2000, BBVA acquired Bancomer for $1.75 billion. Its competitor, SCH bought Serfin in 2001 for $1.56 billion. In 2001, Citigroup purchased Banamex for $12.55 billion. HSBC spent $1.14 billion to take on financial group Bital. It is a fact that these reorganizations reinforce the oligopolistic structure of the banking systems, hence increasing the market power of the large foreign banks compared with local competitors (Calderón and Casilda, 2000). This intensification of banking concentration keeps intermediation spreads high, in turn increasing borrowers' financing costs. Furthermore, the need to maximize equity profitability imposed by parent company shareholders constitutes a continual pressure to improve the financial profitability of the whole group.

This concentration also poses numerous challenges for regulators. They exercise their controlling authority at a national level and experience difficulties in controlling multinational banks whose strategic command post is abroad and whose openness is sometimes lacking. The systemic risk caused by the size of the international banks could incite the supervisory authorities in the host countries to intervene more frequently than in the past, on the basis of the "too big to fail" doctrine (Plihon et al., 2006). As these authors point out, applying this principle leads to excessive risks being taken (moral hazard) inasmuch as it might be the rest of the community which would have to suffer the consequences of these banks' strategies, and not the multinational banks themselves.

Conclusion

Compared with the multinational corporations that bring with them their capital, technologies and methods of governance, the multinational banks possess specific assets which they transfer abroad. In Latin America, the international banks have, in certain aspects, helped strengthen financial stability by disseminating new risk-management methods, by introducing new control procedures and reinforcing the solidity of the asset base within banking systems. Conversely, their preference for liquid assets and public-sector securities and their aversion to counter-party risk have limited their allocation of credit to the private sector. How can investment projects and consumption be financed if credit provision is restricted and expensive? This situation is all the more detrimental to the financing of Latin America's development in that the capital markets, given their shallowness, are mainly the reserve of privileged corporate operators.

As we have observed, foreign banks can be the originators of new sources of financial fragility such as the exposure to foreign exchange risks, increasing market power and perpetuating high intermediation spreads. Yet, the creation of a banking oligopoly under foreign control, as in Mexico, makes it more complicated for the supervisory authorities to take preventive management action against systemic risk. Would the parent companies of the multinational banks always fulfill their role as lenders of last resort towards their subsidiaries or branches if another Latin American banking crisis were to erupt? There have been examples where parent companies have helped their subsidiaries directly without asking host country authorities for assistance. Argentina's crisis in 2002 shows that foreign banks are sometimes able to abandon their branches or subsidiaries.

Supervision requires closer cooperation between host and home country authorities, particularly in banking systems dominated by foreign banks. This cooperation is easier when supervisors have the same independence or when they use common modes of communication. Host country authorities complain that they do not know enough about the domestic implications of international operations carried out by multinational banks or about the specific situation of parent banks in home countries9. Moreover, the cooperation will have to be more intensive about the regulation of offshore financial institutions which increase systemic risk by capitalizing on regulatory arbitrage opportunities. Future jurisdictions could be inspired by the legislation of some countries that already allow authorities not to give licenses to banks with corporate structures that cannot be supervised.

References

Barth J. R., Plumiwasana L T., Yago G., "The foreign conquest of Latin American banknotes: what's happening and why?", Working Paper, n° 171, Centre For Research on Economic Development and Policy Reform , Stanford University, July 2003. [ Links ]

BIS (Bank for International Settlements), 76th Annual Report, Basel, Switzerland, 2006 [ Links ]

Calderón A., Casilda R., "La estrategia de los bancos españoles en América Latina", Revista de la CEPAL, n° 70, April 2000, pp. 71-89. [ Links ]

Calvo G., Fernández-Arias E., Reinhart C. and Talvi E., "The growth-interest rate cycle in the United States and its consequences for emerging markets", Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department, Working Paper 458, 2001. [ Links ]

CEPAL, "La inversión extranjera en América latina y el Caribe, 1999", Santiago, Chile, 2000 [ Links ]

----------, "La inversión extranjera en América latina y el Caribe, 2002", Santiago, Chile, 2003. [ Links ]

Clarke G., Cull R., D'Amato L., Molinari A., "The effect of foreign entry on Argentina's domestic banking sector", Policy Research Working Paper 2158, The World Bank, August 1999. [ Links ]

Clarke G., Cull R., Martínez Peria M.S., Sánchez S., "Foreign Bank entry; experience, implications for developing economies, and agenda for further research", The World Bank Research Review Observer, vol. 18, n° 1, 2003, pp. 25-29. [ Links ]

Claessens S., Demirguc-Kunt A., Huizinga H., "How does foreign entry affect domestic bank-note markets?" Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 25, 2001, pp. 891-911. [ Links ]

Correa E., "Cambios en el sistema bancario en América Latina: características y resultados" in "Claves de la Economía Mundial", 2004, Instituto Español de Comercio Exterior (ICEX), Madrid, Spain. [ Links ]

----------, "Banca extranjera en América Latina", in E. Correa and A. Girón (eds), "Reforma financiera en América Latina", 2006, Clacso Libros y Colección Edición y Distribución Cooperativa, México. [ Links ]

----------, Vidal G., Reform and Structural Change in Latin America: Financial Systems and Instability, in L.P. Rochon and S. Rossi (eds), "Monetary And Exchange Rate Systems: A Global View of Financial Crises", 2006, Edward Elgar Publishing Inc., Northampton, USA. [ Links ]

Crystal J. S., Dages G., Goldberg L.S., "Does foreign ownership contribute to sounder banks in emerging markets? The Latin American experience", Conference on "open doors: foreign participation in financial systems in developing countries", April 19 2001. [ Links ]

De Luna Martínez J., "Las crisis bancarias de México y Corea del Sur", Foro Internacional, vol. XLII, enero-marzo, 2002, pp. 99-153. [ Links ]

De Nicoló. G, Honohan P., Ize A. (2003) "Dollarization of the banking system: good or bad?", IMF Working Paper, WP/03/146, International Monetary Fund, July 2003. [ Links ]

Domanski D., "Foreign banks in emerging market economies: changing players, changing issues", BIS Quaterly Review, December 2005, pp. 69-81. [ Links ]

Focarelli D., "The pattern of foreign entry in the financial markets of emerging countries", central bank paper submitted for the CGFS Working Group on foreign direct investment in the financial sectors of emerging market economies, 2003 (http://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs22cbpapers.htm). [ Links ]

Focarelli D., Pozzolo A..F., "The patterns of cross-border bank mergers and shareholdings in OECD countries", Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 25, 2001, pp. 2305-2337. [ Links ]

Galindo A., Micco A., Serra C., "Better the devil you know: Evidence on entry costs faced by foreign banks", Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department, Working Paper 477, 2003. [ Links ]

García Herrero A., Navia Simón D., "Determinants and impact of financial sector FDI emergency economies: a home country's perspective", Working Group on Financial FDI of the bis Committee of the Global Financial System (CGFS), September 2003. [ Links ]

Gnos C., Rochon L-P, "The Washington consensus and multinational banking in Latin America", Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, vol. 27, n° 2, 2004, p. 315-331. [ Links ]

Grubel H.G., "A theory of multinational banking", Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quaterly Review, n° 123, December 2007, pp. 349-363. [ Links ]

Guillén M., Tschoegl A., "A last the internationalization of retail banking? The case of the Spanish banks in Latin America", Wharton Financial Institutions Center, Working Paper, n° 99-41, 1999. [ Links ]

Haber S., Musacchio A., "Foreign banks and the Mexican Economy, 1997-2004", Working Paper, n° 267, Stanford Center For International Development, November 2005. [ Links ]

Hawkins J., Mihaljek D., "The banking industry in the emerging market economies: competition, consolidation and systemic stability: an overview", BIS Papers, n° 4, Bank for International Settlements, August 2001, pp. 1-44. [ Links ]

IMF, "International capital market developments, prospects and key policy issues", International Monetary Fund, Washington 2000. [ Links ]

----------, "Global Financial Stability Report", International Monetary Fund, Washington, September 2006. [ Links ]

----------, "Global Financial Stability Report", International Monetary Fund, Washington April 2007. [ Links ]

Jeanneau S., "Some prudential issues" in "Evolving banking systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: challenges and implications for monetary policy and financial stability", BIS Papers, n° 33, Bank for International Settlements, February 2007, pp. 52-63. [ Links ]

Jeffers E., Pastre O., "La TGBE, la Tres Grande Bagarre bancaire Européenne" , Economica, Paris, 2005. [ Links ]

Levine R., "International financial liberalization and economic growth", Review of International Economics, vol. 9, n° 4, November 2001, pp. 688-702. [ Links ]

Levy Yeyati E., Micco A., "Concentration and foreign penetration in Latin American banking sectors: impact on competition and risk", Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department, Working Paper 499, 2003. [ Links ]

Mihaljek D., "Privatization", BIS Papers, n° 28, Bank for International Settlements, August 2006, pp. 41-65. [ Links ]

Minda A."Régulation prudentielle internationale et prévention des crises bancaires en Amérique latine", Problèmes d'Amérique Latine, n° 50, Autumn, 2003, pp. 11-137. [ Links ]

----------, Truquin S., "International regulation and supervision: a solution to bank failure in Latin America?", Nordic Journal of Latin America and Caribbean Studies , vol. 35, September 2005, pp. 9-36. [ Links ]

Moguillanski G., Studart R., Vergara S., "Comportamiento paradójico de la banca extranjera en América Latina", Revista de la CEPAL, n° 82, April 2004, pp. 19-36. [ Links ]

Peltier C., "Les banques en Amérique latine: pourquoi si peu de crédit alloué au secteur privé?" Conjoncture, BNP Paribas, August, 2005, pp. 25-46. [ Links ]

Plihon D., Couppey-Soubeyran J., Saidane D., "Les banques, acteurs de la globalisation financière", La documentation Française, Paris, 2006. [ Links ]

Salama P., "Le défi des inégalités, Amérique Latine/Asie: une comparaison économique", Editions La Découverte, Paris, 2006a. [ Links ]

----------, "Pourquoi une telle incapacité d'atteindre une croissance élevée et régulière en Amérique latine?", Revue Tiers Monde, n° 185, 2006b, p. 155-181. [ Links ]

Sebastian M., Hernansanz C., "The Spanish bank strategy in Latin America", Société Universitaire Européennes de Recherches Financiéres, Vienna, 2000. [ Links ]

Weller C. E., "The supply of credit by multinational banks in developing and transition economies: determinants and effects", Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Discussion Paper n° 16, United Nations, New York, 2001. [ Links ]

Wezel T., "Foreign bank entry into emerging economies: an empirical assessment of the determinants and risk predicated on German FDI Data", Discussion Paper, series 1: Studies of the Economic Research Centre, n° 1, Deutsche Bundesbank, 2004. [ Links ]

1 Given the mass of empirical literature, we shall only quote the most representative authors. Readers can refer to García Herrero and Navia Simón (2003) for a more complete review of the literature.

2 Cf. the acquisition of Abbey National by Banco Santander Central Hispano, of Banca Antoneveneta by ABN Amro, of BNL by BNP Paribas or of Crédit Uruguay Banco by Crédit Agricole.

3 See Salama (2006a) for demonstration and the causes of these disparities in Latin America.

4 By way of example, Bank of America took a 9% holding in the capital of the China Construction Bank, BNP Paribas acquired almost 20% of Nanjin City Commercial Bank, and Société Générale now owns 75% of Apeejay Finance.

5 In addition to the Citibank-Travelers merger, Bank of Boston, JP Morgan, and Chase Bank also restructured during this period.

6 Conversely, foreign banks can facilitate capital flight by the intermediation of transactions conducted between subsidiaries and the parent company.

7 In 2005, savings rates as a proportion of GDP stood at 40.6% in the Middle East, 38.3% in Asia, 23.5% in Africa, 22.0% in Latin America and 18.8% in Central and Eastern Europe (IMF, 2006).

8 De Nicoló et al. (2003) show that highly dollarized banks are characterised by higher insolvency risks and higher deposit volatility.

9 See Jeanneau (2007) for prudential issues of relevance to Latin America.