INTRODUCTION

Silversides of the Menidiini tribe (Family Atherinopsidae), are separated into four genera: Chirostoma, Labidesthes, Menidia and Poblana. The monophyly of this group has been supported by morphological (Chernoff, 1986; Dyer, 1997; White, 1985) and allozyme analyses (Crabtree, 1987), but there is uncertainty as to the taxonomic validity of the genera and species of the tribe due to a lack of robust morphological diagnostic characters (Echelle & Echelle, 1984), especially between Poblana and Chirostoma.

The taxonomy of Chirostoma is quite complex (Barbour, 1973) and it has, on several occasions, been separated into two or three genera (Álvarez, 1970; Jordan & Evermann, 1896). Meek (1904) recognized a single genus and set its species in three subgenera, though Jordan & Hubbs (1919) did not find enough evidence to recognize the subgenera. De Buen (1945) classified three genera and six subgenera, and Barbour (1973, 1974) established a single genus with 18 species contained in two groups: jordani and arge. Echelle & Echelle (1984) later discussed an unpublished study of Barbour where he mentioned that Poblana was a synonym of Chirostoma and, based on an allozyme analysis, they suggested that Chirostoma and Poblana should be subsumed under the name Menidia, and they also highlight that the atherinids on the Mexican Central Plateau comprise, with Menidia peninsulae Goode & Bean 1879, a monophyletic group that excludes all other species of Menidia.

Coyote-Hidalgo (2000) analyzed the taxonomic relationship between Poblana and Chirostoma using RAPD markers and observed at intergeneric level that 0.87% of these were exclusive for both genera and since the molecular space of variability presented a strong overlap, concluded that a taxonomic review is necessary to determinate its actual status. Later, Miller et al. (2005) grouped all the silversides of the Central Plateau under the name Menidia.

Bloom et al. (2009) assessed the monophyly of the tribe Menidiini and phylogenetic relationships among their genera and species, using the mitochondrial ND2 gene, in this study the monophyly of the tribe was supported. Menidia and Chirostoma were not recognized as monophyletic, and a central Mexican clade inclusive of Chirostoma and Poblana was recovered as monophyletic. The genus Poblana formed a monophyletic group, within a larger clade that included Chirostoma arge Jordan & Snyder 1899, C. contrerasi Barbour 2002 and C. riojai Solórzano & López 1965 to the exclusion of other species of Chirostoma. This study rejected the hypothesis of Barbour (1973) about of a diphyletic origin of Chirostoma (jordani and arge groups). The authors mention that the close relationship of Menidia to Central Plateau silversides (Chirostoma and Poblana) seem to support a recent origin such as a connection between the Central Plateau and the Rio Grande (= Rio Bravo).

Bloom et al. (2012) used mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data to generate a phylogeny for seven of the eight families of Atheriniformes, including the family Atherinopsidae which they did not recognize as monophyletic. However, in the phylogeny it was observed that a species of Poblana was nested within Chirostoma.

Campanella et al. (2015) supported the monophyly of the tribe Menidiini, but at the generic level they do not support the monophyly of Chirostoma, Poblana and Menidia, suggesting also necessary revisions to the taxonomy. In addition, the phylogenetic relationships obtained in this study propose a new classification of families of Atheriniformes and subfamilies, tribes and genera of Atherinopsidae, such is the case of Chirostoma and Poblana considered as synonyms of Menidia.

Morphometrical studies have addressed the morphological variation of the members of the “humboldtianum group” (Barriga-Sosa et al., 2002; Alarcón-Durán et al., 2017) and Chirostoma grandocule Steindachner 1894 (Barriga-Sosa et al., 2004) but, to our knowledge, there is no information on morphological variation between different genera of the silversides. Thus, the purpose in the present study was to examine the taxonomic validity of Chirostoma, Poblana and Menidia using geometric morphometric data. Specifically, we tested if body shape data could distinguish Poblana from Chirostoma and Menidia. Finally, we assessed the degree of morphological variation between Poblana and Chirostoma. So the differences between the three genera and their species were tested using geometric morphometrics analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish collection. Specimens of Chirostoma were obtained from the Colección Nacional de Peces del Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNPE-IBUNAM). Specimens of Poblana and Chirostoma jordani Woolman 1894 (Villa del Carbon, Mexico State) were obtained from the Colección de peces de la Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (FES-Z). Specimens of Menidia were provided by Manuel Castillo from the Colección del Laboratorio de Peces de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Iztapalapa (UAM-I).

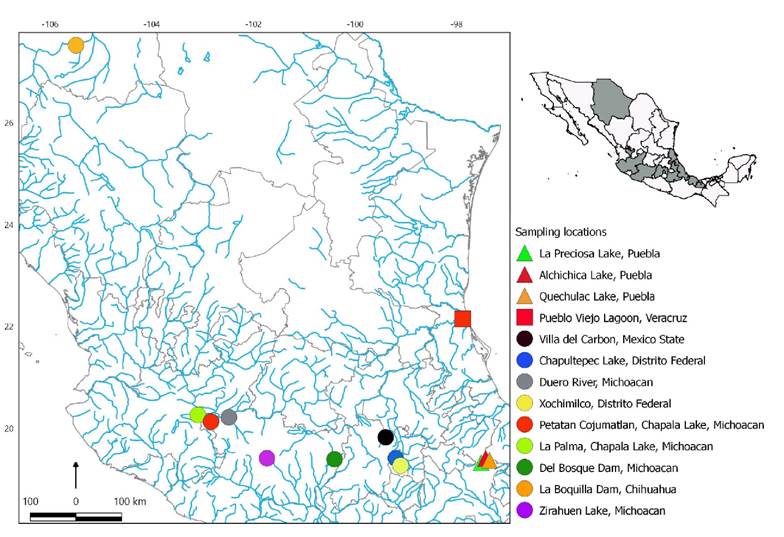

We examined 393 specimens that had been previously identified at the institutions mentioned above, of which 216 belonged to the genus Chirostoma, 150 to Poblana and 27 to Menidia. We obtained a total of 12 species (1 species of Menidia, 3 of Poblana and 8 of Chirostoma). The localities from which species were collected could be seen in Table 1 and Figure 1. For our study only well-preserved samples with no damage or deformations were selected, as well as those collected over a short period to avoid variations generated by the passing of time. For this reason, only the species described in Table 1 were analyzed, being aware that there are other representative species for the three genera.

Table 1 Sample characteristics, sample size (N), range, mean and Std. of standard length. Superscripts correspond to the sampling sites in Chapala Lake: 1= (PCC) Petatan and Cojumatlan; 2= (PLC) La Palma.

| Species | Nomenclature Authors | Locality | Key name | Sampling date | Catalog number | N | Length range (cm) | Mean±std. (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poblana letholepis | Álvarez 1950 | La Preciosa Lake, Puebla | Ple-LCP | 2002 | No voucher | 50 | 4.1-5.3 | 4.8±0.31 |

| P. alchichica | de Buen 1945 | Alchichica Lake, Puebla | Pal-LCA | 2004 | No voucher | 50 | 3.8-5.3 | 4.4±0.38 |

| P. squamata | Álvarez 1950 | Quechulac Lake, Puebla | Psq-LCQ | 1995 | No voucher | 50 | 4.1-5.4 | 4.8±0.29 |

| Menidia beryllina | Cope 1867 | Pueblo Viejo Lagoon, Veracruz | Mbe-PV | 1990 | No voucher | 27 | 4.5-6.1 | 5.2±0.41 |

| Chirostoma jordani | Woolman 1894 | Villa del Carbon, Mexico State | Cjo-SLP | 1980 | No voucher | 34 | 3.8-5.1 | 4.5±0.32 |

| Chapultepec Lake, Mexico City | Cjo-LVC | 1986 | 3662 | 4 | 4.6-5.5 | 5.1±0.39 | ||

| Duero River, Michoacan | Cjo-CRD | 1986 | 10442 | 18 | 3.8-5.1 | 4.4±0.34 | ||

| Xochimilco, Mexico City | Cjo-XDF | 2012 | 18171 | 8 | 4.4-5.4 | 4.8±0.28 | ||

| C. humboldtianum | Valenciennes 1835 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan1 | Chu-PCC | 1985 | 2709 | 15 | 5.9-9.6 | 8.0±1.08 |

| Chapala Lake, Michoacan2 | Chu-PLC | 1985 | 7245 | 9 | 5.6-7.0 | 6.3±0.47 | ||

| Del Bosque Dam, Michoacan | Chu-PBM | 1983 | 2036 | 6 | 9.8-12.8 | 11.2±1.10 | ||

| C. consocium | Jordan & Hubbs 1919 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan1 | Cco-PCC | 1985 | 2706 | 17 | 5.7-9.2 | 7.4±0.88 |

| Chapala Lake, Michoacan2 | Cco-PLC | 1985 | 2693 | 4 | 7.0-7.8 | 7.3±0.37 | ||

| C. promelas | Jordan & Snyder 1899 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan | Cpr-PCC | 1985 | 2707 | 6 | 6.8-9.1 | 8.0±0.89 |

| C. chapalae | Jordan & Snyder 1899 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan1 | Cch-PCC | 1985 | 2705 | 50 | 6.1-8.7 | 7.4±0.56 |

| Chapala Lake, Michoacan2 | Cch-PLC | 1985 | 2698 | 6 | 5.7-9.8 | 7.3±1.45 | ||

| C. lucius | Boulenger 1900 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan | Clu-PLC | 1985 | 2697 | 3 | 15.1-17.9 | 16.6±1.43 |

| C. labarcae | Meek 1902 | Chapala Lake, Michoacan | Cla-PLC | 1985 | 2694 | 15 | 5.6-6.8 | 6.3±0.37 |

| La Boquilla Dam, Chihuahua | Cla-PBC | 1967 | 7227 | 10 | 9.3-11.5 | 10.6±0.66 | ||

| C. estor | Jordan 1879 | Zirahuen Lake, Michoacan | Ces-LZM | 1991 | 10203 | 11 | 8.3-11.1 | 9.5±0.84 |

Figure 1 Sampling locations in the high plateau of Central Mexico. Colored symbols represent the localities for each specie described in the Table 1. The shape of the symbol corresponds to each genus: Triangle = Poblana; Square = Menidia; Circle = Chirostoma.

The specimens were stained with methylene blue to better observe every anatomical structure. The digitalization of each specimen was carried out using a 14 mexapixel Pentax camera. Seventeen landmarks were located over the fish anatomy (Fig. 2 a, b). The anatomical landmarks were assigned following a homology criterion, that is, the landmarks were the same for all specimens (homology in geometric morphometrics sensu stricto) by which these structures are homologous for the three genera, apart from being easily identifiable and similar to those used by Barbour (1973), Rodríguez-Ruíz & Granado-Lorencio (1988), Alaye-Rahy (1993), Soria-Barreto & Paulo-Maya (2005) and Crichigno et al. (2013).

Figure 2 Location of the 17 homologous landmarks recorded on each individual for the analysis of geometric morphometry a) Landmark definitions used in the body of each individual; b) Landmark definitions used in the anterior region.

Morphometric analysis. The configurations of the landmark coordinates for the 393 specimens were scaled, translated and rotated using Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA). To eliminate the variation associated with the size of the specimens it was computed the multivariate allometric regression and a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) of residuals, later we visualize the Principal Components scores (PCs) and use them as the input to a Discriminant Analysis (DA). The latter was computed using PAST (PAleontological STatistics Version 4.06) (2021). The principal component (PC) scores were labeled for the genera and species in order to describe the distribution of the specimens. The extremes of each PC were then used to reconstruct the expected shapes of the landmark configurations with those particular scores. The reconstruction was made by adding the products of these PC scores (PCs) and the eigenvectors for those PCs to the mean tangent coordinates before projecting back from the tangent to the configuration space (O’Higgins et al., 2001). The differences in shape between the mean and the shapes represented by the extremes of the PCs of interest were visualized using deformation grids (Bookstein, 1989; Marcus et al., 1996; Dryden & Mardia, 1998) and computed using MORPHOLOGIKA2 (O’Higgins & Jones, 2006).

The scores of the specimens on all the non-zero PCs were submitted to a Discriminant Analysis (DA) (SPSS v.18.0.0) to examine the potential that differences in shape may have in classifying unknown specimens. Generalized ‘Mahalanobis’ distances and discriminant functions were then computed to assess the efficacy of the discriminant analysis in the classification. The discriminant analysis was carried out using a cross-validation approach in which multiple repeated analyses were carried out leaving out one individual in the construction of the discriminant function before classifying this individual according to the function. The exclusion of an individual reduces the likelihood of overestimating the efficacy of the discriminant functions by using them to classify specimens employed in their construction (Ibáñez et al., 2009). This approach was applied to each genus and species, and the percentages of correct classification rates were recorded.

The configurations of the landmark coordinates for each genus were scaled, translated and rotated using a GPA to obtain the consensus configuration (a single set of landmarks which represents the central tendency of an observed sample; i.e., each genus). The morphometric distance matrix of Procrustes distances (the square root of the sum of squared differences between the positions of the landmarks in two optimally superimposed configurations at centroid size) among consensus configurations was then calculated by genus. In addition, the Chirostoma jordani Procrustes distances were compared with the genera Poblana and Menidia.

RESULTS

The standard length (SL) values of the Poblana, Menidia and Chirostoma jordani populations were similar, varying from 3.8 to 6.1 cm. All other species of Chirostoma were larger in size, C. consociumJordan & Hubbs 1919, C. promelas Jordan & Snyder 1899 and C. chapalae Jordan & Snyder 1899 from 5.7 to 9.2, 6.8 to 9.1 and 5.7 to 9.8 cm respectively. Larger specimens were represented by C. labarcae Meek 1902 (range: 5.6-11.5 cm); C. humboldtianum Valenciennes 1835 (range: 5.6-12.8 cm); C. estor Jordan 1879 (range: 8.3-11.1 cm) and especially C. lucius Boulenger 1900 for which the largest size of 15.1-17.9 cm was recorded (Table 1).

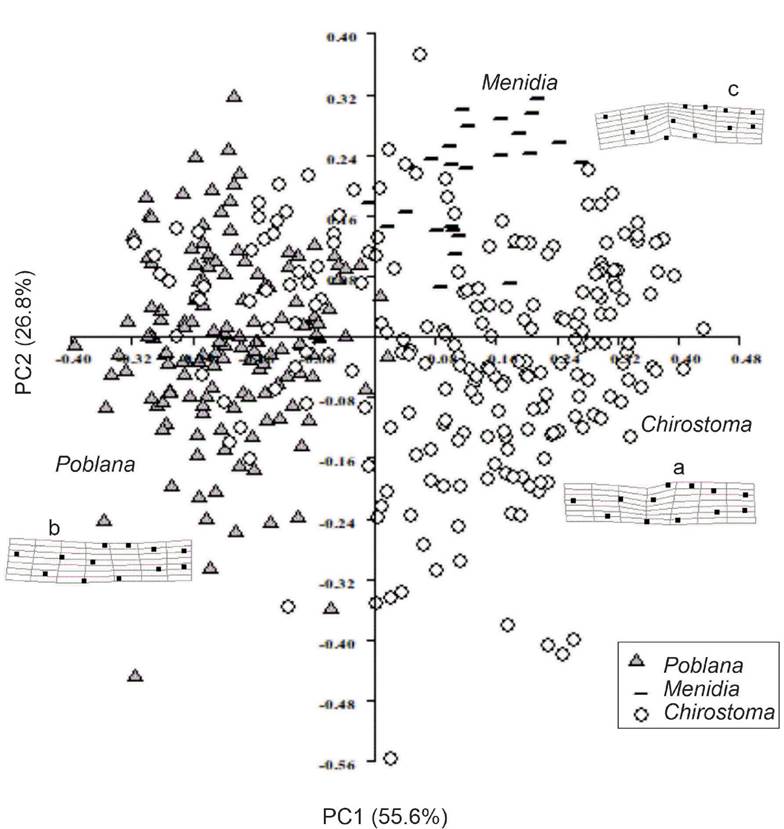

Genus Level Classification. The PCA among genera (Fig. 3) indicated that the first two components explained 82.4% of the total variance with the first component explaining 55.6% and the second 26.8%. A clear separation of the genera Poblana and Menidia with some overlap with specimens of Chirostoma was observed for the two first principal components (Fig. 3) in particular specimens from Poblana overlaps mainly with C. jordani.

Figure 3 First two principal components (PCs) of fish shape labelled by genus. Thin plate spline deformation grids for the extreme points of each PC are shown; these are superimposed on the shapes predicted when the average landmark configuration of all specimens is deformed into that of a hypothetical specimen positioned at the extreme of the point of interest: a= Chirostoma. b= Poblana. c= Menidia.

The general pattern of morphological differences described by these first two PCs was explored using transformation grids (Fig. 3). Lm 1 moves more to dorsal zone in Menidia, as well the Lm 2-4 forms a more pronounced arc in Chirostoma than in the other two genera. In Menidia specimens there is a relative displacement of the Lm 7 towards the ventral area (Fig. 3a, c). Transformation grids (Fig. 3a, c) show the mean shape of Chirostoma (Fig. 3a), Poblana (Fig. 3b) and Menidia (Fig. 3c) specimens. The genus Chirostoma presented a greater variation in landmarks 2 and 3 (space of the predorsal fins). In Chirostoma, the pectoral fin had a dorsally leaned position near landmark 2. Pectoral fin shape in Menidia and Poblana was very similar to the mean shape: almost at the same height as landmark 1, although in every case the end of the pectoral fin (landmark 7) occurred before the pelvic fin (landmark 9). Landmarks 10 and 11 (anal fin base) also presented variations: in Poblana it was thinner and getting closer to the caudal fin from landmark 11, while in Chirostoma it was thicker and in Menidia it remained almost like the mean shape.

Procrustes distances among genera showed that Menidia and Chirostoma are more similar to each other (0.0432 radians), followed by Poblana and Menidia (0.0492 radians) and lastly Poblana and Chirostoma (0.0519 radians). On the other hand, the Procrustes distances matrix among Poblana, Menidia and Chirostoma jordani showed that Poblana and Menidia to be more similar to each other (0.0492 radians), followed by Menidia and C. jordani (0.0549 radians), while that Poblana and C. jordani are less similar (0.0625 radians).

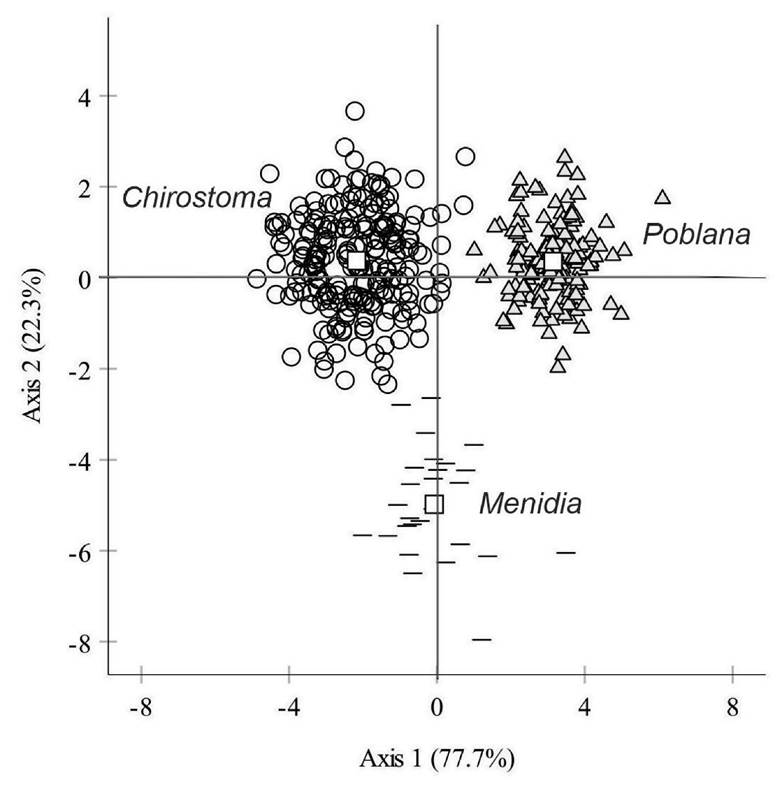

Overall discrimination by cross-validated grouped cases was 98.5%. The three genera clearly separate from each other (Wilks’ λ = 0.047, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The 97.7% of the specimens of Chirostoma were correctly classified only with one specimen classified as Menidia (0.5%) and four as Poblana (1.9%). The 96.3% of the specimens of Menidia were correctly classified only with one specimen classified as Chirostoma (3.7%) while Poblana was 100% classified (Table 2).

Figure 4 Plot of first and second axis of the discriminant analysis among Poblana, Chirostoma and Menidia. White square are centroids of each genus.

Table 2 Classification results for the discriminant analysis with the cross-validation testing procedure (cross-validated) for the 3 genera: Poblana, Menidia and Chirostoma. Total classification success for cross-validated predicted genus variant membership. In bold the diagonal values.

| Predicted Group Membership | ||||

| Genus | Poblana | Menidia | Chirostoma | Total |

| Poblana | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Menidia | 0 | 96.3 | 3.7 | 100 |

| Chirostoma | 1.9 | 0.5 | 97.7 | 100 |

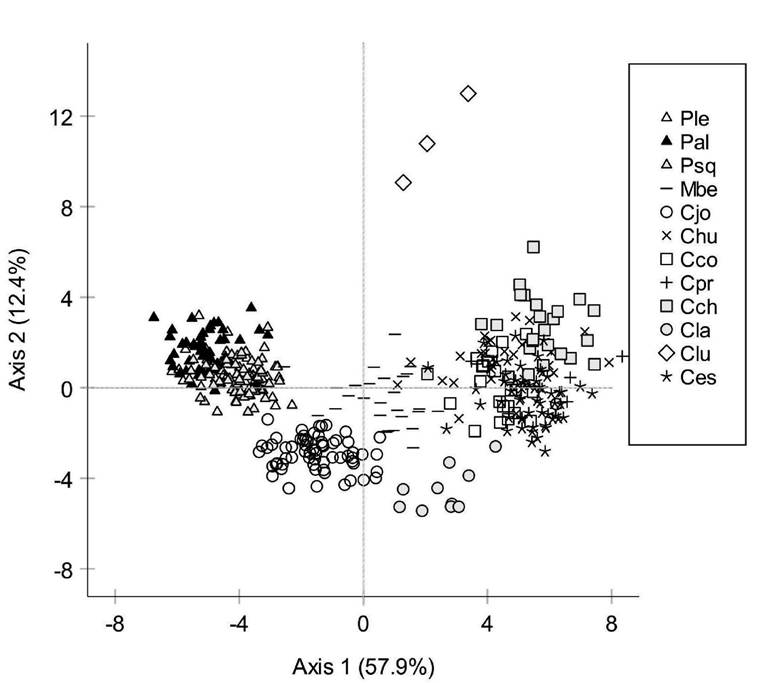

Species Level Classification. The cross-validated analysis showed 84.2% of classification by species (Table 3). Misclassifications occurred within each genus (Fig. 5; Table 3). Individuals of Poblana letholepis Álvarez 1950, P. alchichica de Buen 1945 and P. squamata Álvarez 1950 formed a group apart from the other species. Menidia beryllina Cope 1867, Chirostoma jordani and C. labarcae were better classified with 100% of the cross-validation, C. lucius and C. chapalae grouped with 90.9% and 76.0% respectively. The species with lower percentages of discrimination were Chirostoma estor with 73.2%, C. humboldtianum with 63.3% (20% similar to C. chapalae), C. promelas with 50.0% (with 33.3% and 16.70% of misclassification with each C. humboldtianum and C. estor) and C. consocium with 47.6% (38.1% similar to C. estor). Differences among species were highly significant (Wilks’ λ = 4.7 x 10-5, p < 0.001).

Table 3 Classification results for the discriminant analysis with the cross-validation testing procedure (cross-validated) for the 12 species: Poblana letholepis= Ple. Poblana alchichica= Pal. Poblana squamata= Psq. Menidia beryllina= Mbe. Chirostoma jordani= Cjo. Chirostoma humboldtianum= Chu. Chirostoma consocium= Cco. Chirostoma promelas= Cpr. Chirostoma chapalae= Cch. Chirostoma lucius= Clu. Chirostoma labarcae= Cla. and Chirostoma estor= Ces. Total classification success for cross-validated predicted species variant membership. In bold the diagonal values.

| Predicted Group Membership | ||||||||||||||

| Species | Ple | Pal | Psq | Mbe | Cjo | Chu | Cco | Cpr | Cch | Clu | Cla | Ces | Total | |

| Ple | 92.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Pal | 0 | 96.0 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Psq | 10.0 | 8.0 | 82.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Mbe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Cjo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Chu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63.3 | 13.3 | 0 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 100 | |

| Cco | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 47.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38.1 | 100 | |

| Cpr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.70 | 100 | |

| Cch | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 76.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Clu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.9 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Cla | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | |

| Ces | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 | 16.1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 73.2 | 100 | |

Figure 5 First two axes of the discriminant analysis of fish shape labelled by species. Key names of species as in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The discriminant analysis present evidence that morphometric variation significantly separates the genera Poblana, Chirostoma and Menidia. In common with the results obtained, this separation indicates the differences in the shape of the three genera and agrees with the genetic analysis of Bloom et al. (2009) in which they maintain Chirostoma and Poblana as independent, highlighting that are closely related, so they support a recent origin such as a connection between the Central Plateau and the Rio Grande. In more recent times, Bloom et al. (2012) used genetic analyses to confirm that Poblana is nested within Chirostoma. Campanella et al. (2015) formally included Poblana and Chirostoma within Menidia, confirmed that Poblana is nested within Chirostoma, and proposed that neither genus is valid as they are both members of Menidia, following Miller et al. (2005).

Guerra-Magaña (1986) taxonomically analyzed 18 morphological characters in species of Poblana and populations of Chirostoma jordani and found a clear differentiation of the two groups at the genus level. Our study agrees with that differentiation and it is, at the time, the first approximation of geometric morphometrics that discriminates Poblana, Chirostoma and Menidia. Nevertheless, our results statistically discriminate between the shapes of the Poblana species, for which reason we do not concur in considering them as subspecies of the Poblana genus, as Guerra-Magaña (1986) mentioned.

Phenotypic traits are essential for identifying discrete phenotypic entities. Our results show that Poblana and Chirostoma jordani are statistically different morphs, i.e., each one keeps its own identity, though C. jordani grouped preferentially with Poblana, in contrast with the other species of Chirostoma.

The Central Plateau is a region that has been subdivided several times according to its geographical, hydrological and ichthyological features (Díaz-Pardo et al., 1993). It is generally established that these subdivisions favored the fragmentation of different populations of fish that followed their own evolutionary history after they were isolated. Thus, the genera Chirostoma and Poblana are examples of these endemic monophyletic groups. There are other examples of this fragmentation in different populations, i.e., in goodeids (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2008), catostomids (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2016), poecilids (Beltrán-Lopéz et al., 2018), Chirostoma attenuatum (Betancourt-Resendes et al., 2018) and the “humboldtianum” clade (Betancourt-Resendes et al., 2019) between others. Several authors have proposed hypotheses that try to explain the origin of both Poblana and Chirostoma. Smith & Miller (1986) suggested that a species resembling Menidia penetrated Mexican continental waters from the Atlantic coast through the Rio Bravo in the Pliocene-Pleistocene. Back then, the Rio Bravo was connected with the Central Plateau. Afterwards, this communication was interrupted, and populations were isolated, diverged, dispersed and reached a wide distribution throughout the Central Plateau. The isolation of the populations then resulted in the genera Chirostoma and Poblana. This hypothesis supports the results obtained in this study where Chirostoma and Poblana have different shapes.

The Procrustes distances matrix among genera determined that Poblana and Chirostoma are less alike to each other (with a greater distance between them) and Menidia and Chirostoma are the most similar. The Procrustes distances indicated a lower similarity between Poblana and Chirostoma jordani and a greater similarity between Poblana and Menidia. The results also show that the mean shapes of Poblana-Chirostoma and Poblana-C. jordani are more different than those of the other genera, supporting the idea of Poblana and Chirostoma being morphometrically different.

Chirostoma estor, C. humboldtianum, C. promelas and C. consocium were species that showed the lowest value of discrimination with greater overlapping with other species, these results could be related to high degree of morphological polymorphism of the atherinopsid’s species (Barriga-Sosa et al., 2002; Bloom et al., 2009). Additionally, morphological differences within species have been closely linked to habitat adaptations related with swimming mode where body shapes are associated to lentic and lotic habitats (Fluker et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2015; Alarcón-Durán et al., 2017), these same characteristics could explain the changes in form at the genus level.

We found significant divergent morphometrics in the sampled silversides which were useful in discriminating genera and species despite the strong genetic relationships. Phenotypic variations are a product of genotype and environment interactions. They are thus a complex and important biological phenomenon that is still poorly studied. Although not all species of Poblana, Chirostoma and Menidia were incorporated in this study, significant morphometric differences were found at genus level.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)