Introduction

Many species of seaweeds, mainly brown algae, are widely used in agriculture as plant biostimulants, plant growth regulators, biofertilizers, or metabolic enhancers (Hong et al., 2007). Seaweed extracts can act by increasing plant vigor and vitality due to the presence of several bioactive substances that are important for plants (Khan et al., 2009; Gupta & Abu-Ghannam, 2011). Also, they can improve nutrient uptake from soil (Turan & Köse, 2004). There are many advantages of using seaweed extracts as stimulants of plant growth, including higher germination rates, root-system development, increased leaf area, fruit quality, and plant vigor (Hong et al., 2007; Rayorath et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2009; Craigie, 2011; Vinoth et al., 2012a, b; Mattner et al,. 2013; Vinoth et al., 2014). Besides this, plants treated with seaweed extracts have a higher content of biochemical constituents such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, protein, and amylases (Zhang & Schmidt, 2000; Thirumaran et al., 2009; Gireesh et al., 2011), and treated plants acquire more resistance against pathogens (Jayaraj et al., 2008; Vera et al., 2011a, b; González et al., 2013a, b; Satish et al., 2015a, b; Ali et al., 2016).

As these beneficial effects are obtained with small doses of seaweed extracts, it is suggested that the active compounds could be growth hormones that occur naturally in seaweeds, such as auxins, cytokinins, gibberellins, or other low molecular weight components (polyamines and brassinosteroids) that are also effective at low concentrations (Hernández-Herrera et al., 2016). In addition, higher components identified in algal extracts such as polyphenols (phloroglucinol and its derivate eckol) promote growth activity, as well as polysaccharides (alginate, fucoidan, laminaran, and carrageenans, or their derived oligosaccharides) exhibit the same growth promotion activity (Hong et al., 2007; Khan et al., 2009; Craigie, 2011; González et al., 2013b; Rengasamy et al., 2015a, b). Other studies also indicate that the biostimulants effect is synergistically produced by all extract components: carbohydrates, proteins, minerals, vitamins, fatty acids, and phytohormones (Fornes et al., 2002; Zamani et al., 2013).

Recently in Mexico, the use of seaweed derivatives as biostimulants, biofertilizer, metabolic enhancer, and root promoters are included in crops as an alternative to the use of synthetic fertilizers, in order to reduce ecosystem degradation and contamination of agricultural land (Hernández-Herrera et al., 2014a). These reports show that a better understanding of their biological mode of action may enhance productivity in the future. The status and context for seaweed applications in Mexican agriculture are presented here.

Diversity of seaweed flora with potential as biofertilizers

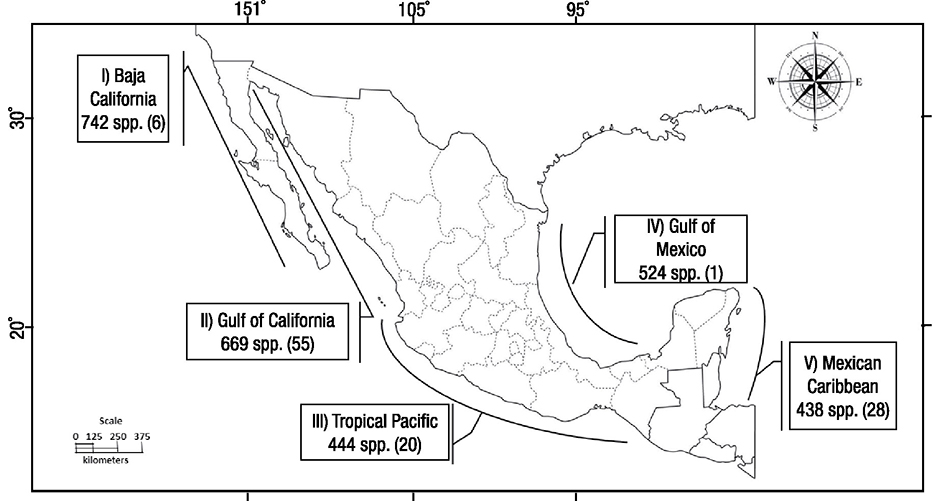

Mexico is the only Latin American country with temperate, subtropical, and tropical seas; thus, no other country in this region has such diversity in the marine environment (Robledo et al., 2013). The coastline of Mexico extends for ~11,500 km (7,146 miles) and the exclusive economic zone covers approximately 3 million square kilometers. Five geographic regions in temperate to tropical latitudes with distinctive physiographic, geological, and climatic conditions favor the existence of a diverse algal flora. I) Baja California has an extensive latitudinal range and varied climatic patterns with the richest seaweed flora and large potential; 60 species cited as economically important are present (Aguilar-Rosas, 1982). II) The Gulf of California is considered an area of abundant seaweed with potential economic value; at least 55 species have commercial application (Pacheco-Ruíz & Zertuche-González, 1996) and there is high biomass which can be harvested sustainably. III) The Tropical Pacific is characterized by an impoverished phycoflora, with most species in the Rhodophyta and Phaeophyceae taxonomic groups (Pedroche & Sentíes, 2003). Of the few studies addressing economic potential of seaweed none occur in the tropical region of Nayarit and Jalisco. Respectively, these areas have 16 and 4 species with potential for exploitation to produce seaweed liquid extracts for agriculture (Pacheco-Ruíz & Zertuche-González, 1996; Hernández-Herrera et al., 2014a; Nicolás-Álvarez et al., 2014; Hernández-Herrera et al., 2016). However, algal biomass, populations, and ecological studies of seaweeds with economic interest are unknown for the region. IV) In the Gulf of Mexico, the flora has a continuous distribution (Garduño-Solórzano et al., 2005) represented by species of Ulva as having economic potential. V) The Mexican Caribbean has cold and warm water currents, influencing the distributional pattern of seaweeds, which is associated with the littoral and sub-littoral rocky areas; 28 species of seaweed with economic interest are recognized on the Yucatan coast (Robledo-Ramírez & Freile-Pelegrín, 1998). The richest seaweed flora and potential for seaweed utilization in Mexico is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Seaweed flora in the five geographic regions of Mexico according to Pedroche and Sentíes (2003). The number of seaweeds with potential economic value appears in parenthesis.

Management and regulations in mexico for the exploitation and harvesting of seaweed

In Mexico, the federal government manages all fisheries, including seaweed. However, under a law published in 2009, individual states can also manage sessile marine resources through an agreement with the federal government (Calvillo-Unna, 2009). Currently in Mexico, artisans carry out the harvest of this resource. For example, since 1966, Chondracanthus canaliculatus (Harvey) Guiry has been harvested by hand at low tide for carrageenan production. It is a sustainable harvest to date in San Quintin, Baja California. Aquaculture and harvesting of Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex P.C.Silva in Dzilam de Bravo, Yucatan, is done by both men and women (Robledo et al., 2013; Rebours et al., 2014). At present, the harvest of this resource (such as in the case of Gelidium robustum (Gardner) Hollenberg et Abbott and Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh in Baja California), is carried out with small boats, where two fishermen using knives cut the upper portion of the alga; the maneuver typically requires 2 to 4 hours of labor (SAGARPA, 2012).

The mexican seaweed extract industry

In Mexico, the use of seaweed at an industrial level started in the first half of the last century. The agar industry began in 1941 with the Alga-Mex company (Osorio-Tafall, 1946) harvesting the ‘red sargazo’ Gelidium robustum by diving. Currently, G. robustum is the only algae processed in Mexico by the company Agarmex. The giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera along with other algae of the genus Sargassum were initially exploited in Isla Todos Santos (Baja California), where potassium salts were obtained for agricultural purposes (Ortega, 1987), but the industry began in 1956 harvesting kelp as a source of alginates. One decade later, locals started harvesting Chondracanthus canaliculatus as a source of carrageenan, by hand during low tide.

For almost four decades, the Mexican industry remained in good shape; however, some important changes occurred in 2004, because the alginate industry shut down in the USA (CP Kelco), causing Mexico to stop exporting M. pyrifera. From 1956 to 2004, an annual average of 3,000 tons were harvested, using a boat designed specifically to harvest the available biomass, cutting the surface frond at one meter below the surface. The closing of this activity led to the search for other uses for M. pyrifera, such as the production of a supplement for balanced meals to feed red abalone [Haliotis rufescens (Swainson)]. The production of seaweed liquid extracts for application in agricultural crops also started. At present, Mexico’s seaweed biomass, such as Gelidium robustum and Chondracanthus canaliculatus is sold to the phycocolloid industry for agar and carrageenan extraction (SAGARPA, 2012; Zertuche-González et al., 2014). At present, G. robustum and M. pyrifera are used by the Algas Pacific company (http://algaspacific.com/) located in Ensenada in Baja California state, to produce seaweed liquid extracts, which are sold as a plant growth biostimulant. None of the four commercial seaweed species harvested in Mexico (M. pyrifera, G. robustum, C. canaliculatus, Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis (Bory de Saint-Vincent) E.Y. Dawson, Acleto y Foldvik) is endangered, thanks to the application of proper harvesting methods (Hernández-Garibay et al., 2006; Robledo & Townsend, 2006; SAGARPA, 2012).

Seaweed liquid fertilizer production is carried out by the private sector, which harvests and processes its raw materials. There are few companies working on liquid fertilizer production, employing ~10 fishermen in algal harvesting and processing, from which about 20 more families benefit. The use of raw materials for food benefits about 20 families directly and indirectly, and it is increasing (SAGARPA, 2012).

Algal biomass from six seaweed species are used to produce 14 commercial products (SAGARPA, 2012) such as biostimulants, biofertilizers, and root promoters (Table 1). According to our research, the production of commercial products in Mexico is based on algae biomass by conventional solvent extraction and hydrolysis with several methods under hydrothermal treatment with acid, neutral, and alkaline conditions.

Table 1 Commercial seaweed products produced in Mexico.

| Product name | Seaweed species | Manufacturer | Application | pH/color | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgroKelp® | Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh | Algas y Bioderivados Marinos, S.A de C.V | Biostimulant Biofertilizer | 4.3-4.6 Dark brown liquid |

Khan et al. (2009), Sharma et al. (2014) |

| AlgaenzimssupMR | Sargassum spp., desert plants and salts | Palau Bioquim, S.A. de C.V | Biofertilizer | Unspecified |

Sunapri et al. (2010), Villarreal-Sánchez et al. (2003) |

| Algamar® |

Ascophyllum nodosum (Linnaeus) Le Jolis, Sargassum spp., Laminaria spp., M. pyrifera, and Egregia menziesii (Turner) Areschoug |

Química Sagal, S.A. de C.V | Biostimulant | 8.7-9.3 Black powder |

In this study |

| AlgarootMR | Sargassum spp., desert plants and salts | Palau Bioquim, S.A. de C.V | Root promoter | Unspecified liquid | In this study |

| CuajaenzimsMR | Sargassum spp., desert plants and salts | Palau Bioquim, S.A. de C.V | Biostimulant | Unspecified | In this study |

| FrutoenzimsMR | Sargassum spp., desert plants and salts | Palau Bioquim, S.A. de C.V | Biostimulant | Unspecified | In this study |

| KelproMR |

M. pyrifera and E. menziesii |

Tecniprocesos Biológicos, S.A. de C.V | Biostimulant | 4.4 | Khan et al. (2009), Sharma et al. (2014) |

| Kelprolizer® |

M. pyrifera, liquid fish protein and humic acid |

Productos del Pacífico, S.A de C.V | Blend organic fertilizer | 4.5-5.0 | In this study |

| Kelproot® |

M. pyrifera and Gelidium robustum (Gardner) Hollenberg et Abbott |

Algas y Extractos del Pacífico Norte, S.A. de C.V | Root promoter | 2.0 to 12.5 Dark brown liquid |

In this study |

| Kelprosoil® | M. pyrifera | Productos del Pacífico, S.A de C.V | Biostimulant | Brown to greenish liquid | Khan et al. (2009), Sharma et al. (2014) |

| NPKelp® |

M. pyrifera and G. robustum combined with Yucca schidiger a Roezl ex Ortgies and humic acid |

Algas y Extractos del Pacífico Norte, S.A. de C.V | Biofertilizer | 4.5-5.1 Dark brown liquid |

In this study |

| Seaweed® | M. pyrifera | Algas Marinas, S.A. de C.V | Biostimulant | 4.0-4.5 brown | In this study |

| TurboenzimsMR |

Sargassum spp., desert plants and salts |

Palau Bioquim, S.A. de C.V | Metabolic enhancers | Unspecified | In this study |

| Vitalex® | Unspecified seaweed and hydrolyzed fish | Química Sagal, S.A. de C.V | Biofertilizer | 8.5-9.0 Brown liquid |

In this study |

The effect of seaweed and its derivates on germination and seedling establishment

The seaweed liquid extracts for plant biostimulants produced in Mexico compete with similar products described by other authors. In published research (Table 2), trials were conducted in Mexico with 12 seaweed species to test biostimulant activity on crop growth.

Table 2 Seaweed used as biostimulant in crops.

| Geographic regions | Seaweed used to produce the extracts | Type of extracts | Crops | Beneficial effects under crops | References |

| I Baja California |

Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh |

Alkaline | Bean mung (Vigna radiata) (L.) Wilczek and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Linnaeus) |

Growth promoter | Briceño-Domínguez et al. (2014) |

| Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh | Alcoholic | Red radish (Raphanus sativus Linnaeus) | Root promoter | Hernández-Alarcón (2014) | |

| Ecklonia arborea (=Eisenia arborea J. E. Areschoug) | Alkaline | Bean mung, lettuce (Lactuca sativa Linnaeus) and red radish | Growth promoter | Martínez-Morales (2015) | |

| II Gulf of California | Acanthophora spicifera (M.Vahl) Børgesen | Alkaline | Bean mung, lettuceand red radish | Root promoter | Martínez-Morales (2015) |

| Ulva lactuca Linnaeus | Alkaline | Bean mung, lettuceand red radish | Root promoter | Martínez-Morales (2015) | |

| Ulva lactuca | Acid | Bean mung | Root promoter | Castellanos-Barriga et al. (2017) | |

| III Tropical Pacific |

Caulerpa sertularioides (S. G. Gmelin) M.Howe |

Neutral | Tomato | Enhance germination | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2014) |

| Padina gymnospora (Kützing) Sonder | Neutral | Tomato | Enhance germination | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2014) | |

| Sargassum liebmannii J. Agardh | Neutral | Tomato | Enhance germination | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2014) | |

| Ulva lactuca | Neutral | Tomato | Enhance germination | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2014) | |

| Padina gymnospora | Neutral and alkaline | Bean mung and tomato | Root promoter | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2016) | |

| Ulva lactuca | Neutral and alkaline | Bean mung and tomato | Root promoter | Hernández-Herrera et al. (2016) | |

| Sargassum liebmannii | Neutral | Jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus Linnaeus) | Germination promoter | Nicolás-Álvarez et al. (2015) | |

| IV Gulf of Mexico | Ulva lactuca | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Garduño-Solórzano et al., 2005 |

| V Mexican Caribbean | Hydroclathrus clathratus(C. Agardh) M. Howe | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Robledo-Ramírez y Freile-Pelegrín (1998) |

| Sargassum filipendula C. Agardh | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Robledo-Ramírez y Freile-Pelegrín (1998) | |

| Sargassum fluitans (Børgesen) Børgesen | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Robledo-Ramírez y Freile-Pelegrín (1998) | |

| Turbinaria tricostata E.S. Barton | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Robledo-Ramírez y Freile-Pelegrín (1998) | |

| Turbinaria turbinata (Linnaeus) Kuntze | Unspecific | Unspecific | Growth promoter | Robledo-Ramírez y Freile-Pelegrín (1998) |

The use of liquid seaweed extracts in Mexico began around the 1980s with the commercial product Algaenzims. Canales-López (1999) published a compilation of 12 years of research to find the precise doses of seaweed enzymes and the effects on plants and crop quality, as well as changes in the soil. The results showed a crop increase to 1-3 t ha−1 by supplying from 1-3 L ha−1 of the commercial product produced in the region. Another study by Villarreal-Sánchez et al. (2003) showed that Algaenzims contains a complex of viable (live) sea microorganisms, which includes nitrogen-fixing organisms, halophiles, molds and yeasts, and macro and microelements that highlight the importance of interactions between plants and the microorganisms contained in the product.

Additional research by García-Sahagún et al. (2014) assessed the effect of a commercial product (seaweed) on the development of gerbera (Gerbera jamesonii H. Bolus) under greenhouse conditions. Applying seaweed to gerbera had a positive effect on leaf number, stem number, stem length, and capitulum or flower head diameter (Fig. 2).

Figures 2a-c a) Capitulum harvested according to treatment. From left to right, Seaweed (SW), Alga 600 (A600), Control (T), and Osmocalm (PN); b) Length of stems; c) Diameter of the capitulum. (Photos: María Luisa García Sahagún).

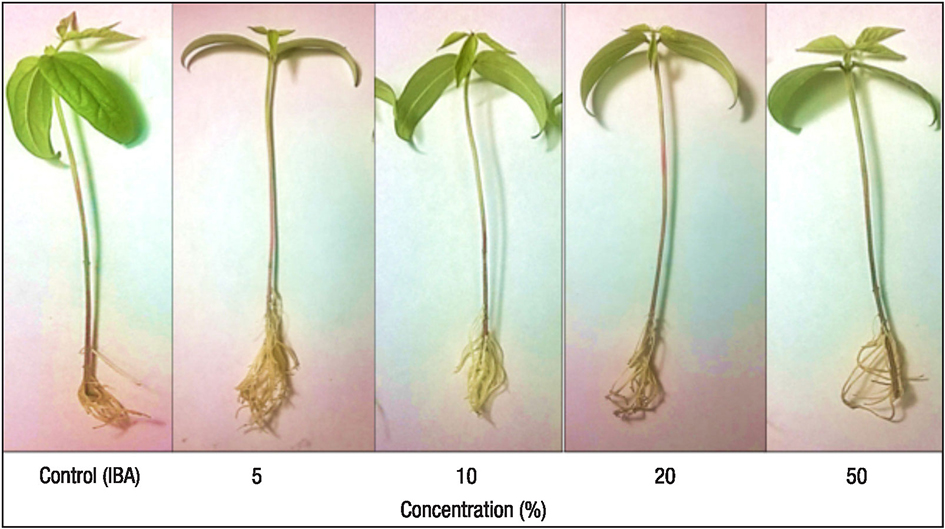

In recent published research by Briceño-Domínguez et al. (2014), a new method was developed to produce an alkaline seaweed liquid extract from M. pyrifera with high polysaccharide content. They suggested scaling up the process to industrial level. The most active extract was produced at pH 12 and 80 °C. Under these conditions the seaweed liquid extract enhanced adventitious root formation in a mung bean cutting assay, similar to the effect of indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) (Figure 3), and increased seedling growth in tomatos. Additionally, Nicolás-Álvarez et al. (2014) also found that a crude extract of Sargassum liebmannii J. Agardh is a potential germination promoter for Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urban.

Figure 3 Activity of the extracts of Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh produced at different pH and temperature on the adventitious root formation from bean mung plants and IBA as reference (control).

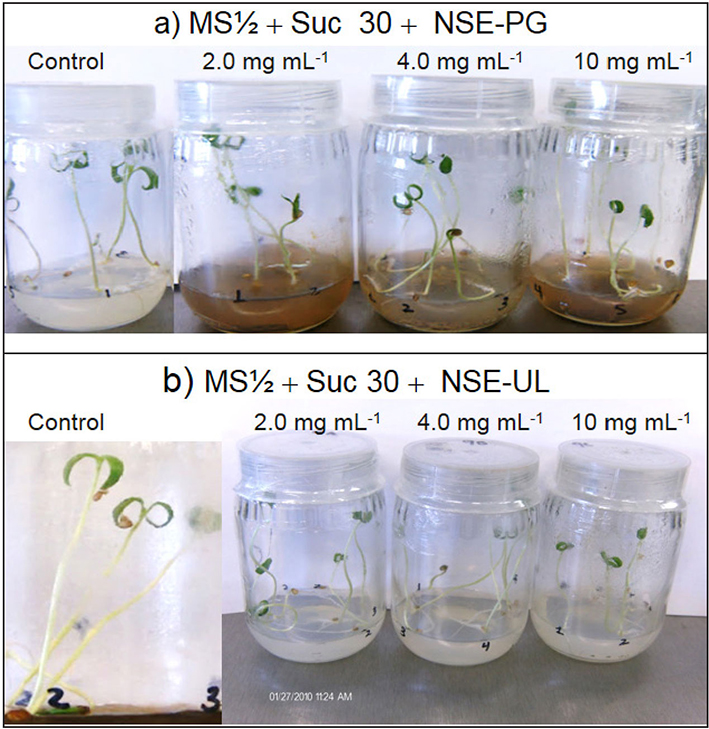

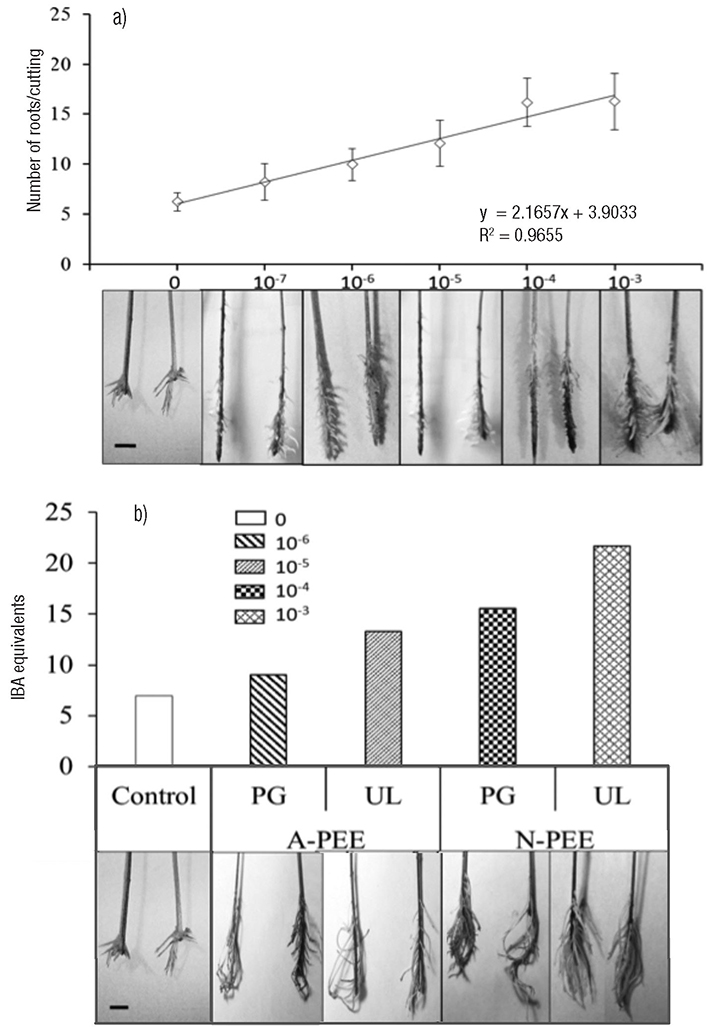

Hernández-Herrera et al. (2014a, 2016) found that neutral and alkaline seaweed extracts as well as polysaccharide-enriched extracts produced with tropical marine algae increased seed germination and tomato plant growth under different culture conditions (Fig. 4). In addition, enhanced adventitious root formation was observed in mung bean cuttings with polysaccharide-enriched extracts obtained with neutral rather than alkaline conditions (Fig. 5). Similarly, acid seaweed extracts increased biochemical parameters (Chlorophyll, total and reducer sugar) in the mung bean (Castellanos-Barriga et al., 2017), as well as seed germination of red radish (unpublished data) (Fig. 6).

Figures 4a-b Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Linnaeus). Seedling growth under culture in vitro after two weeks of incubation exposed to different concentrations of seaweed extracts. a) Plants growing in control (half-strength MS with sucrose at 30 g L-1) and in different concentrations of neutral seaweed extracts from Padina gymnospora (Kützing) Sonder (NSE-PG); b) Neutral seaweed extracts of Ulva lactuca Linnaeus (NSE-UL) combined in half-strength MS with sucrose (30 g L-1).

Figures 5a-b Root inducer activity. a) A standard curve for root formation in mung bean plants treated with indol-3-butyric acid (IBA) at 10−7, 10−6, 10−5, 10−4, and 10−3 concentration (M) as reference; b) IBA equivalents (M) on root formation with polysaccharide-enriched extracts obtained with neutral (N-PEE) and alkaline (A-PEE) conditions from Ulva lactuca Linnaeus (UL) and Padina gymnospora (Kützing) Sonder (PG) at concentration of 1.0 mg mL−1. Values represent the mean of n = 20 seedlings, bars represent standard errors. Bar = 1 cm.

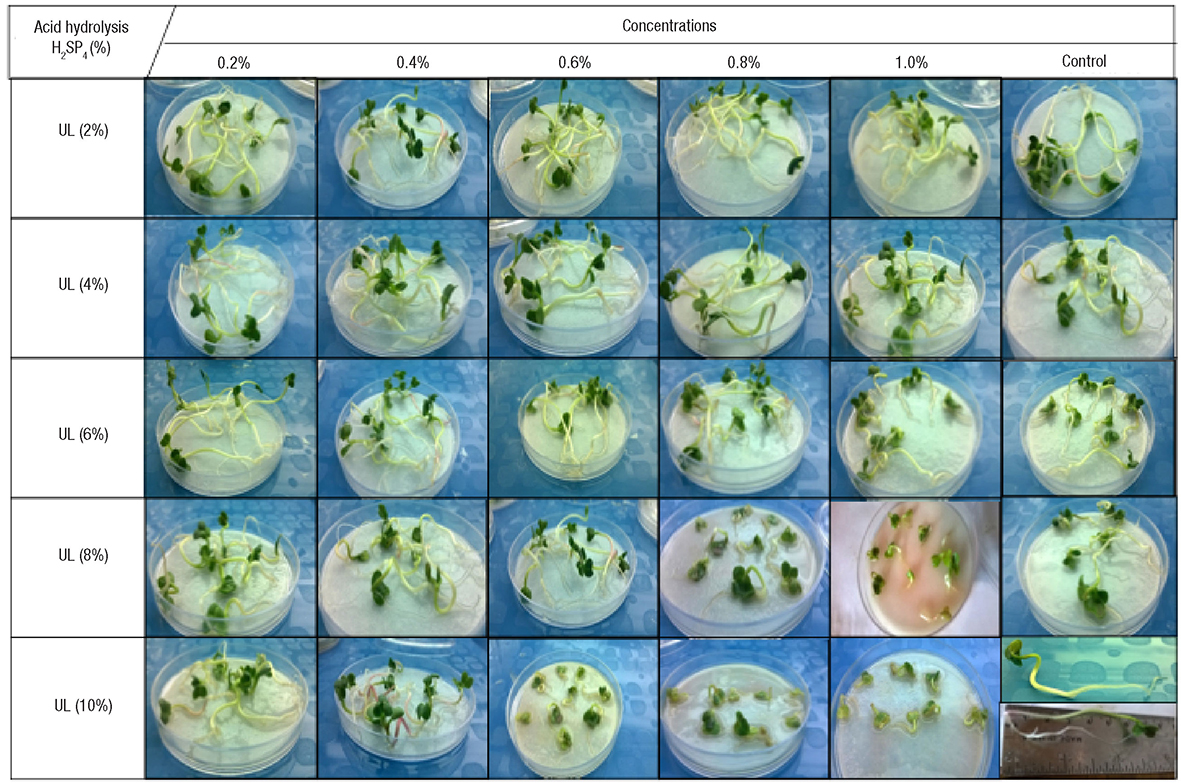

Figure 6 Effect of extracts from Ulva lactuca Linnaeus (UL) obtained with acid hydrolysis conditions (H2SO4 at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 %) at different concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%) on red radish germinate. Best results were obtained with the treatment of UL2 at 0.2%.

The effect of green and brown seaweed extracts as elicitors to protect tomatos (Solanum lycopersicum Linnaeus) against the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria solani (Cooke) Wint. was published in Mexico. The algal extracts increased the defense activity of enzymes and proteinase inhibitors and expression of defense-related genes (Hernández-Herrera et al., 2014b).

Current research of algae extracts on some crops

The effects of both liquid and solid seaweed-derived biostimulants, biofertilizers, and root promoters was studied in Mexico by CICIMAR (Interdisciplinary Center of Marine Sciences of the National Polytechnic Institute, CUCBA (University Center for Biological and Agricultural Sciences, acronym in Spanish) at the University of Guadalajara, and the Technical Superior Institute of Felipe Carrillo Puerto in Quintana Roo state, and included the following species: Macrocystis pyrifera, Ecklonia arborea (Areschoug) M.D. Rothman, Mattio & J.J.Bolton (=Eisenia arborea), Sargassum liebmannii, S. horridum Setchell & N.L. Gardner, S. natans (Linnaeus) Gaillon, S. fluitans (Børgesen) Børgesen, Padina gymnospora (Kützing) Sonder, Chnoospora minima (Hering) Papenfuss, Caulerpa sertularioides (S.G. Gmelin) M. Howe, Ulva lactuca Linnaeus, Acanthophora spicifera (M. Vahl) Børgesen, Gelidium robustum, and Gracilaria parvispora I.A. Abbott. These products were produced by acid, neutral, or alkaline extraction techniques.

The results obtained from this research could be useful to write a best-practice guide for regional agriculturists to improve harvesting quantity and quality in agriculture and horticulture. In conclusion, this review showed that seaweed extracts and polysaccharide-enriched extracts are increasingly used in Mexican crop production. Research in our laboratories demonstrated that crop species respond differently to the extracts (concentration and frequency of application); yet more crop-specific research is required to optimize seaweed extract application and to obtain the best possible outcome (i.e. return on investment). Most of the seaweed extract products currently in the market are extracts of whole seaweed. A number of questions require answers for better use of seaweed resources and their extracts in crops. 1) Does the same raw material processed by different extraction methods lead to extracts with different characteristics? (Briceño-Domínguez et al., 2014; Hernández-Herrera et al., 2016). 2) How long does the effect persist after application of seaweed extracts? (Hernández-Herrera et al., 2014b). 3) Is it possible to combine different extracts from different seaweeds at different concentrations for synergistic effects? (Hernández-Carmona & Di Filippo-Herrera, unpublished). It would also be interesting to study the physiological effects of specific chemical components in order to develop a second generation of seaweed products with specific plant biostimulants activity.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)