Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Hidrobiológica

versión impresa ISSN 0188-8897

Hidrobiológica vol.13 no.4 Ciudad de México dic. 2003

Article

Preliminary data on the culture of juveniles of the dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834)

Resultados preliminares sobre el cultivo del mero, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834)

Vicente Gracia López1 and Francesc Castelló-Orvay2

1Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR). Mar Bermejo 195, Col. Playa Palo Sta. Rita, La Paz, B.C.S. 23090, Mexico.

2Laboratory of Aquaculture. Department of Animal Biology. Faculty of Biology. Universitat de Barcelona. Avda. Diagonal, 645. 08028. Barcelona, Spain.

Recibido: 13 de marzo de 2003.

Aceptado: 18 de septiembre de 2003.

Abstract

This study shows preliminary data about the culture of juvenile dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus. Two experiments were carried out to determine the effects of three salinity levels (35, 27 and 20 psu) and two different temperatures (20 and 26 ºC) on the growth, survival, and feeding parameters of fish raised in concrete tanks. Also, growth, feeding efficiency and biometry was studied for seven grams juveniles in a 15 month trials. Results indicated that fish maintained at a salinity of 35 psu grew faster than fish at 20 and 27 psu, and significant differences in weight gain, feed conversion ratio, protein efficiency ratio, specific growth rate, and survival were obtained between these treatments. Best growth and better feeding parameters were obtained for fish at high temperature. Significant differences in feed conversion ratio, protein efficiency ratio and specific growth rate were obtained between temperature treatments. At the end of the experimental procedure the final mean weight was 458 g in 15 months. Mean weight gain was 451 g and the feed conversion ratio was 1.23. This study also demonstrated a faster growth in culture conditions than in the wild. The results obtained were courageous and could be the basis of further studies for the culture of this species.

Keywords: Grouper, temperature, salinity, growth, Epinephelus marginatus.

Resumen

Este estudio muestra datos preliminares sobre el cultivo de juveniles de mero, Epinephelus marginatus. Dos experimentos se realizaron para determinar los efectos de tres salinidades (35, 27 y 20 uds) y dos temperaturas (20 y 26 ºC) sobre el crecimiento, supervivencia y parámetros alimentarios de peces mantenidos en tanques de cemento. También, el crecimiento, la eficiencia alimentaria y la biometría fueron estudiados en juveniles de siete gramos durante 15 meses. Los resultados obtenidos indicaron que los peces mantenidos en una salinidad de 35 uds crecieron más rápido que los peces a 27 y 20 uds y se hallaron diferencias significativas en el peso ganado, índice de conversión, tasa de eficacia proteica, tasa específica de crecimiento y supervivencia entre esos tratamientos. El mayor crecimiento y los mejores parámetros alimentarios fueron obtenidos en los peces a 26 ºC. Se encontraron diferencias significativas en el índice de conversión, tasa de eficacia proteica y en la tasa específica de crecimiento entre las dos temperaturas. En la prueba de crecimiento, el peso final medio fue de 458 g. El peso medio ganado por pez fue de 451 g en 15 meses con un índice de conversión del alimento de 1.23. Este estudio también demostró un crecimiento más rápido en condiciones de cultivo que en condiciones naturales. Los resultados obtenidos son alentadores y pueden ser la base de estudios más profundos sobre el cultivo de esta especie.

Palabras clave: Mero, temperatura, salinidad, crecimiento, Epinephelus marginatus.

Introduction

In some countries, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834) and other grouper are considered as a delicious and highly marketable fish. Over fishing and other environmental factors have produced a decrease of grouper in the Mediterranean. Capture of this species in Spain decreased from 605 TM (1978) to 0 TM (1986) (FAO, 1991). However, from 1990 a small number of grouper juveniles have appeared along the coast of Barcelona, Spain (Castello et al., 1992; Gracia, 1996). An established population of dusky grouper in a marine reserve on the coast of Catalonia (Zabala et al., 1997b) and the reproduction of this species in this area (Zabala et al., 1997a) could partially facilitate the recuperation of this species.

The geographical distribution of E. marginatus includes warm and temperate waters, within tropical and subtropical areas, found on the eastern and western coast of the Atlantic Ocean, and throughout the Mediterranean Sea (Heemstra, 1991). Concerning temperature it can be found in areas that range from 12 to 25ºC (Zabala et al., 1997b) and it can be maintained in aquariums for artificial reproductive purposes between 12 and 24ºC (Glamuzina et al., 1998c). In general, grouper species distribution include waters where the temperature is warmer than the western Mediterranean sea waters (Chua & Teng, 1980; Lim, 1993; Ellis et al., 1997).

Dusky grouper could be found generally offshore (Gracia, 1996) and sometimes in estuarine environments (Boutan, 1927) and in lakes and lagoons with a high marine influence (Lozano Cabo, 1953). Usually, other grouper species have been found and cultured at salinities similar and lower than those reported for E. marginatus (Chua & Teng, 1980; Morizane et al., 1984; Manzano, 1990).

Water temperature and salinity are the most important physical factors that influence fish growth. An Increase in growth has been reported due to increased water temperature for Nassau grouper (Ellis et al., 1997), and several fish species. Lower salinities than seawater have also been found to affect fish, leading to increased growth (Chua & Teng, 1980; Alliot et al., 1983).

Groupers, and other fish species, could have different growth depending on the environmental conditions of their habitat. Wild dusky grouper, spent approximately 3.3 years to attain 400 g (Bruslé, 1985), and other groupers spent from 1 to 2 years for obtaining the same size (Manooch & Haimovici, 1978; Salazar & Sanchez, 1988). Due to this fact, growth of wild groupers could be considered slow for aquaculture purposes. However, in culture conditions, the right management of the physical parameters along with the knowledge of the nutritional requirements is the main key to obtain a faster growth of fish.

Interest of the culture and the biology of dusky grouper has been increased and research has focused preliminary on the culture results of feeding trials (Castello et al., 1992), ecology (Chauvet, 1988; Gracia, 1996; Zabala et al., 1997a; Zabala et al., 1997b), artificial reproduction, and egg and larval development (Skaramuca et al., 1989; Spedicato et al., 1995; Glamuzina et al., 1998a; Glamuzina et al., 1998b; Glamuzina et al., 1998c).

Little or no information exists about the effects of temperature and salinity on the growth of this species. The objective of this paper was to determine the effects of salinity and temperature on growth, feeding parameters and survival of juveniles of E. marginatus and to raise juveniles in captivity to commercial size, studying feeding parameters, growth rate and biometrics along the trial.

Materials and methods

Experimental Fish. Juveniles of dusky groupers were collected in shallow waters (approximately 12 m depth) at the Maresme, north of Barcelona, Spain in 1992. There were three sampling methods used to obtain juveniles. Fish could be found in small holes and cavities of oyster larvae collectors, as these were recovered. Also, the individuals were captured underwater spraying anesthetic (Quinaldine) to the water near the fish. In addition, traps were laid on the bottom to obtain them. After capture, fish were transferred to a cylindrical plastic container with supplementary aeration and transported to the laboratory.

Culture tanks. Fish were maintained in a 475-L rectangular concrete tanks, for temperature and salinity trials. For the growth trial, 100-L rectangular glass aquariums and 1,000 L rectangular plastic tanks were used. Each tank was provided with an external biofilter composed of fiber, active charcoal, sand, and supplemental aeration that was provided by a compressor. PVC pipes (20cm length, eight cm diameter) were placed on the bottom of the tanks to provide hiding places for the fish.

Food and feeding methods. First, fish were fed with fresh squid and fish. Afterwards, commercially grow feed for sea bream, Sparus aurata (Ewos Company) was added replacing the fresh feed. Composition of the pellets is shown in table 3. Experimental fish were fed ad libitum twice daily (10:00 and 19:00 hours). Pellets were slowly given to the fish. Uneaten pellets were collected by siphoning and were counted. The difference between the initial number of pellets and the amount of uneaten pellets was taken as the number of pellets eaten by the fish.

Experimental design. To test the effect of salinity on growth and feeding parameters, three different salinities were used in the first experiment (35, 27 and 20 psu) on juveniles of 46 g mean weight for 45 days (Table 1). The second experiment tested the effect of temperature (20 and 26ºC) on 65 g juveniles for 60 days (Table 2). For each temperature and salinity, two replicates were used. For the growth trial, fifty-six juveniles (7.1 g) were stocked in four 100 L rectangular glass aquariums in an indoor laboratory at a density of 14 fish/aquarium for 90 days. At the end of this period, the 48 fish remaining (25.2 g) were moved to four 475 L rectangular concrete tanks (12 fish/tank) for 162 days. Finally, 44 fish were transferred to a two 1,000 L rectangular plastic tanks situated outdoors for 198 days. Tanks were maintained at a temperature of 24.1 ± 1.9ºC.

Measurements. Body weight was measured every 15 days since the beginning of the study. In the growth trial, standard length, total length, cephalic length, and maximum height of the fish were also measured every 15 days. Before being measured the fish were anaesthetized using 50 mg/L of tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222).

Data analysis. The data were used to calculate weight gain per fish, feed conversion ratio, specific growth rate, protein efficiency ratio and survival. These terms were defined as follow: Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated as: dry weight of feed eaten / wet weight gained; specific growth rate (SGR): 100 (lnWf - lnWi) / days, where Wf = final weight of fish and Wi = initial weight of fish; and protein efficiency ratio (PER) was calculated as: wet weight gained/dry weight of protein consumed.

Means among treatments were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and if significant differences were found, then the differences between means were analysed (P < 0.05) with the Newman-Keuls test. Percentage data were arcsine transformed before the analysis.

For the growth trial, regression analyses between weight-time, weight-standard length and weight-total length were calculated and the correlation factor and equation were reported. In the experiments, water temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen were measured daily. Levels of ammonia and nitrite were measured on alternate days.

Results

Salinity. Growth of fish at a salinity of 35 psu was higher than those at salinities of 27 psu and 20 psu, after 45 days. Weight-gain per fish was 10.92, 6.01 and 3.5 g, respectively. There was a significant difference in final weight (P < 0.05) between fishes at 35 psu with those at 27 psu and 20 psu; no significant differences were observed between the 27 and 20 psu treatments (P > 0.05). Table 1 shows the results of the effect of salinity on growth, survival and feeding parameters. Specific growth rate was higher for fish at a salinity of 35 psu (0.44), followed by fish at 27 psu (0.27) and 20 psu (0.16). Results of FCR and PER were better for fish at salinity of 35 psu. Temperature was maintained at 19.1ºC, the ammonia and nitrite levels lower than 0.1 mg/L and continuous aeration maintained oxygen levels higher than 5.6 mg/L.

Temperature. Weight-gain per fish was 31.1 g at 26ºC (25.9±1.8ºC) and 16.1g at 20ºC (20.4±1ºC). The weight-gain at the highest temperature was 93.16 % greater than at the lowest temperature. However, no significant differences were found (P > 0.05) for the final mean weight between these two temperatures. Table 2 resumes main results of the effect of temperature on growth, survival and feeding parameters. The fish at the highest temperature obtained the best SGR and PER. Significant differences in feed conversion ratio, protein efficiency ratio and specific growth rate were observed between temperature treatments. Survival was 100 % at both temperatures. Salinity was maintained at 35 psu, the ammonia and nitrite levels lower than 0.1 mg/L and continuous aeration maintained oxygen levels higher than 5 mg/L.

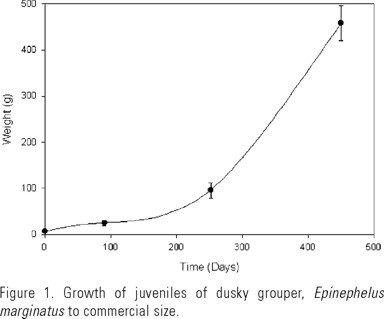

Growth trial. Fish grew from 7.1 g to 458 g in 15 months. Results of initial and final weight, feed conversion ratio, protein efficiency ratio, specific growth rate and survival are shown in table 4. Differences in the three periods were recorded and are discussed in the next section.

The relation between weight and time was calculated and exponential curve Y = exp (2.264+0.00827 X) was obtained with a correlation factor of 0.99. Figure 1 shows the growth of juvenile grouper, E. marginatus in the present study. Regression analyses between weight-standard length was (r2 = 0.98; Y = -3.959 X 3.11 ) and weight-total length was (r2 = 0.98; Y = -4.832 X 3.22).

Discussion

In this study, the level of salinity that produced the higher growth, survival, and the best use of feed in juveniles of dusky grouper, E. marginatus, was 35 psu. Good growth and feeding parameters were obtained at 27 psu for a short period, but a decrease in growth and an increase in mortality after day 30 would discourage the culture of E. marginatus at this salinity level. Salinity of 20 psu was disadvantageous because it produced slow growth, low feeding efficiency and high mortality in few days. This could be related to the fact that this species has been found generally offshore (Cadenat, 1937; Oliver, 1963; Sara, 1969; Bombace, 1970; Gracia, 1996), and rarely in estuarine environments (Boutan, 1927).

The optimum salinity level obtained in the present study is higher than those reported for other cultured groupers. Salinities between three and 27 psu were reported for 3-277 g of E. tauvina juveniles (Manzano, 1990); salinity of 25 psu was determined for E. tauvina at the larval stage (Akatsu et al., 1983); and salinity between from 15-26 psu was observed for E. salmoides of 8.4 to 10 g (Chua & Teng, 1980). Salinities employed in the grouper culture have a direct relation with the salinity of their habitat. E. salmoides is usually found in estuarine waters where the salinity varies from 26-31 psu (Chua et al., 1977); E. malabaricus and E.coioides seem to rest in the same place when salinities ranges from 1 to 42 psu (Sheaves, 1993). Juveniles of dusky grouper demonstrated an ability to tolerate 45 psu for 60 days without mortality (per. comm.). This salinity tolerance is similar than to the 45.5 psu reported for E. salmoides (Chua & Teng, 1980).

Weight-gain of fish that were maintained at high temperature was 93.16 % higher than those at low temperature, and SGR was also higher for these fish. Results of FCR and PER were lower than the FCR (1.06) and PER (1.97) reported for E. malabaricus at temperatures between 26.1 and 27.8ºC, after being fed with artificial feed that contained protein levels between 48 and 52 % (Chen & Tsai, 1994). Results of FCR and PER obtained could improve with the formulation of commercial diets that satisfy the essential nutrition requirements and energy.

The absence of mortality in the experiment indicates that fish could be cultured at temperatures ranging from 20.4 to 25.9ºC. The temperature that provided the best results is lower than the 27-32ºC reported for E. salmoides culture (Chua & Teng, 1980), and the 26-39ºC reported for E. tauvina (Manzano, 1990). But, cage culture of E. akaara in Hong Kong, reports optimum temperatures from 22 to 28ºC (Tseng & Ho, 1988). E. tauvina larvae were cultured in Singapore between 26 to 30ºC (Lim, 1993), while in Japan, water temperature was maintained between 22.8 and 28.6ºC for E. akaara larvae (Morizane et al., 1984). Based on previous results of grouper species, the water temperature for obtaining the optimum growth of E. marginatus could be higher than those tested in this study. Although, mortality could have an increase in such conditions (Chua & Teng, 1980). As temperature rises, fast growth can be achieved, with an increase in the size variation between fish, leading to possible cannibalism. That can be reduced, feeding frequently and adequately, and also reducing culture density (Fukuhara, 1989). On the other hand, low temperature tolerance may be less than 13.5ºC reported for E. salmoides (Chua & Teng, 1980). This is based on the temperatures recorded in the wild for E. marginatus (Zabala et al., 1997b). In laboratory conditions, E. marginatus has been maintained at a temperature of 29ºC, without mortality.

Grouper, E. marginatus, grew 458 g in 15 months under the experimental conditions established in this study. This was faster than growth of Puntazzo puntazzo, which reached 377g in 29 months (Gatland, 1995), and 480 g in 21 months for Pagrus pagrus (Kentouri et al., 1995). Growth of cultured dusky grouper was faster than in the wild, where it spent approximately 3.3 years to reach 400 g (Bruslé, 1985). This is similar to red grouper, E. morio that achieved 480 g in about 2 years, approximately (Salazar & Sanchez, 1988), and gag, Mycteroperca microlepis that attained 400 g in 1.2 years (Manooch & Haimovici, 1978).

Growth of E. marginatus was slower than cultured sea bream, Sparus aurata (Cejas et al., 1993) and had similar growth to sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (Barnabé, 1986), cultured at 25ºC. Assuming that growth on the first life stages is similar to the other cultured species, time of growth for E. marginatus to attain a weight of 450 g, could take 18-20 months. The above mentioned temperature is an important factor that affects growth. Epinephelus sp. spent 10 months to grow from 61.5 to 835.8 g (Yen & Yen, 1985), and E. salmoides individuals can reach a size of 500 g from 15 g, in 8 months (Chua & Teng, 1979). Nutrition and feeding are two of the most important non-environmental factors for the culture and growth of fish. In a previous study (Castelló et al., 1992), growth and FCR of E. marginatus fed the same commercial diet (for sea bream, Sparus aurata) were better than fed with natural feed. Better FCR was obtained in the present study (1.23) perhaps due to the difference in water temperature in both studies. Juveniles were easily adapted to the commercial feed, and small differences in FCR were obtained throughout the fish growth. Feed conversion ratio obtained for E. akaara cultured in Hong Kong was higher than 10 (Tseng & Ho, 1988), and E. salmoides, cultured in Malaysia, fed on trash fresh fish, had a feed conversion next to 4.5 (Chua & Teng, 1982).

The diet used had a 49 % of protein content. It is possible that rising this percentage may enhance growth as studies by Teng et al. (1978), that reported optimum levels of protein of 50 % for E. salmoides and for the Nassau grouper, E. striatus which grew faster with high protein (61.8 %) commercial pellet (Ellis et al., 1996). Specific growth rate was higher than the 0.94 reported for sea bream, S. aurata from egg to 423 g and 0.53 for Pagellus erythrinus in experimental conditions (Cejas et al., 1993). Inversely, other groupers cultured in Asia, E. tauvina and E. fuscoguttatus, presented specific growth rates 3 and 2.5 respectively. This study presents the first data relating some biometric variables for cultured groupers.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere appreciation to many persons who gave time, advice, and support, specially David Martínez. Editing of the English text was provided by Ira Fogel and Margarita Kiewek at CIBNOR in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico. This study was supported by "Dirección general de Pesca, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain".

References

AKATSU, S., K. M. AL-ABDUL-ELAH & S. K. TENG. 1983. Effects of salinity and water temperature on the survival and growth of brown-spotted grouper larvae (Epinephelus tauvina, Serranidae). Journal World Mariculture Society 14: 624-635. [ Links ]

ALLIOT, E., A. PASTOUREAUD & H. THEBAULT. 1983. Influence de la température et de la salinité sur la croissance et la composition corporelle d'alevins de Dicentrarchus labrax. Aquaculture 31: 181-194. [ Links ]

BARNABÉ, G. 1986. Aquaculture. Vol.2. Technique et Documentation, Lavoisier, Paris. [ Links ]

BOMBACE, G. 1970. Notizie sulla malacofauna e sulla ittiofauna del coralligeno de Falesia. 3. I pesci della Falesia e delle "secche" costiere. Quaderni di Ricerca e Sperimentazione Palermo 14: 59-71 [ Links ]

BOUTAN, L. 1927. Trois semaines à l'embouchure de l'Oued Sebaou. Bulletin Station Aquiculture et Pêche de Castiglione 1: 37-114. [ Links ]

BRUSLÉ, J. 1985. Exposé synoptique des données biologiques sur les mérous Epinephelus aeneus (Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, 1809) et Epinephelus guaza (Linnaeus, 1758) de l'Océan Atlantique et de la Méditerranée. FAO Synopsis Pêches 129: 64 p. [ Links ]

CADENAT, J. 1937. Recherches systématiques sur les poissons littoraux de la côte W d'Afrique, récoltés par le navire President Theodore Tissier, au cours de la 5ème croisière (1936). Revue des Travaux de l'Office des Peches Maritimes, Nantes 10(4): 425 p. [ Links ]

CASTELLÓ, F., A. FERNÁNDEZ, F. LLAURADO & R. VIÑAS. 1992. Effect of different types of food on growth in captive grouper (Epinephelus guaza, L.). Marine Life 1(2): 57-62. [ Links ]

CEJAS, J., M. SAMPER, S. JEREZ, R. FORES & J. VILLAMANDOS. 1993. Actas IV Congreso Nacional de Acuicultura. España, 127-132. [ Links ]

CHAUVET, C. 1988. Étude de la croissance du mérou Epinephelus guaza (Linné, 1758) des côtes tunisiennes. Aquatic Living Resources 1: 277-288. [ Links ]

CHEN, H-Y. & J. C. TSAI. 1994. Optimal dietary protein level for the-growth of juvenile grouper, Epinephelus malabaricus, fed semipurified diets. Aquaculture 119: 265-271. [ Links ]

CHUA, T.E., J. E. ONG & S. K. TENG. 1977. A preliminary study of the hidrobiology and fisheries of the straits of Penang. USM Short-term Research Grant Project Report, USM/CTE Nº 1. School of Biological Sciences, University Sains Malaysia, Penang, 24 pp. [ Links ]

CHUA, T. E. & S. K. TENG. 1979. Relative growth and production of the estuary grouper, Epinephelus salmoides under different stocking densities in floating net cages. Marine Biology 54: 363-372. [ Links ]

CHUA, T. E. & S. K. TENG. 1980. Economic production of estuary grouper, Epinephelus salmoides Maxwell, reared in floating net cages. Aquaculture 20: 187-228. [ Links ]

CHUA, T. E. & S. K. TENG. 1982. Effects of food ration on growth, condition factor, food conversion efficiency, and net yield of estuary grouper, Epinephelus salmoides Maxwell, cultured in floating net cages. Aquaculture 27: 273-283. [ Links ]

ELLIS, S.C., G. VIALA & W. O. WATANABE. 1996. Growth and feed utilization of hatchery-reared juvenile Nassau grouper fed four practical diets. The Progressive Fish-Culturist 58: 167-172. [ Links ]

ELLIS, S. C., W. O. WATANABE & E. P. ELLIS. 1997. Temperature effects on feed utilization and growth of postsettlement stage Nassau grouper. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 126: 309-315. [ Links ]

FAO, 1991. Bulletin of Fishery Statistics 31. 210 p. [ Links ]

FUKUHARA, O. 1989. A review of the culture of grouper in Japan. Bulletin of Nansei Regional Fisheries Research Laboratory 22: 47-57. [ Links ]

GATLAND, P. 1995. Growth of Puntazzo puntazzo in cages in Selonda bay, Corinthos, Greece. Cahiers Options Mediterraneennes 16: 51-55. [ Links ]

GLAMUZINA, B., B. SKARAMUKA, N. GLAVI & V. KO UL. 1998a. Preliminary studies on reproduction and early stages rearing trial of dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834). Aquaculture Research 29: 769-771. [ Links ]

GLAMUZINA, B., N. GLAVI, V. KO UL & B. SKARAMUKA. 1998b. Induced sex reversal of the dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834). Aquaculture Research 29: 563-568. [ Links ]

GLAMUZINA, B., B. SKARAMUKA, N. GLAVI, V. KO UL, J. DULI & M. KRALJEVI. 1998c. Egg and early larval development of laboratory reared dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834) (Pisces, Serranidae). Scientia Marina 62(4): 373-378. [ Links ]

GRACIA, V. 1996. Estudio de la biología y posibilidades de cultivo de diferentes especies del género Epinephelus. Tesis de doctorado en Biología. Facultad de Biología. Universitat de Barcelona. Barcelona, España. 279 p. [ Links ]

HEEMSTRA, P. C., 1991. A taxonomic revision of the eastern atlantic groupers (Pisces: Serranidae). Boletim do Museu Municipal do Funchal 43 (226): 5-71. [ Links ]

KENTOURI, M., M. PAVLIDES, N. PAPANDROULAKIS & P. DIVANACH. 1995. Culture of the red porgy, Pagrus pagrus, in Crete. Present knowledge, problems and perspectives. Cahiers Options Mediterraneennes 16: 65-75. [ Links ]

LIM, L. C. 1993. Larviculture of the greasy grouper Epinephelus tauvina F. and the brown-marbled grouper E. fuscoguttatus F. in Singapore. Journal World Aquaculture Society 24: 262-274. [ Links ]

LOZANO CABO, F. 1953. Notas sobre una campaña de prospección pesquera en la mar Chica de Melilla. Boletin del Instituto Español de Oceanografía 64: 3-37. [ Links ]

MANOOCH III, CH.S. & M. HAIMOVICI. 1978. Age and growth of the gag, Mycteroperca microlepis, and size-age composition of the recreational catch off the southeastern United States. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 107 (2): 234-240. [ Links ]

MANZANO, V. B. 1990. Polyculture systems using grouper (Epinephelus tauvina) and tilapia (Tilapia mossambicus) in brackishwater ponds. In HIRANO, R., HANYU, I. (eds). Proceedings of the Second Asian Fisheries Forum, Tokyo, Japan. pp. 213-216. [ Links ]

MORIZANE, T., A. TAKASAKI & H. UCHIMURA. 1984. Artificial propagation of grouper. Bulletin of the Ehime prefectural fisheries experimental station 1983: 144-150. [ Links ]

OLIVER, M. 1963. Note bathymétrique et bionomique sur le banc Baudot. General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean. Proceedings and Technical Paper 40: 413-416. [ Links ]

SALAZAR, A. & J. SANCHEZ. 1988. Aspectos biológico pesqueros del mero Epinephelus morio de la flota artesanal de las costas de Yucatán, México. Proceedings of the 41st Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, 422-430. [ Links ]

SARA, M. 1969. Il coralligeno pugliese e suoi rapporti con l'ittiofauna. Bolletino dei Musei e degli Istituti Biologici dell'Università di Genova 37: 27-33. [ Links ]

SHEAVES, M. J. 1993. Patterns of movement of some fishes within an estuary in tropical Australia. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 44: 867-880. [ Links ]

SKARAMUCA, B., D. MUSIN, V. ONOFRI & M. CARI. 1989. A contribution to the knowledge on the spawning time of the dusky grouper, (Epinephelus guaza L.). Ichthyologia 21 (1): 79-85. [ Links ]

SPEDICATO, M. T., G. LEMBO, P. DI MARCO & G. MARINO. 1995. Preliminary results in the breeding of dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834). Cahiers Options Mediterraneennes 16: 131-148. [ Links ]

TENG, S. K., T. E. CHUA & P. E. LIM. 1978. Preliminary observation on the dietary protein requirement of estuary grouper, Epinephelus salmoides Maxwell, cultured in floating net cages. Aquaculture 15: 257-271. [ Links ]

TSENG, W. Y. & S. K. HO. 1988. The biology and the culture of red grouper. Chien Cheng Publisher. Taiwan, R.O.C. 134 p. [ Links ]

YEN, J. L. & J. C. YEN. 1985. Cage culture of some marine economic fishes in Penghu. Bulletin Taiwan Fisheries Research Institute 38, pp. 157-166. [ Links ]

ZABALA, M., A. GARCÍA-RUBIES, P. LOUISY & E. SALA. 1997a. Spawning behaviour of the Mediterranean dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834) (Pisces, Serranidae) in the Medes Islands Marine Reserve (NW Mediterranean, Spain). Scientia Marina 61 (1): 65-77. [ Links ]

ZABALA, M., P. LOUISY, A. GARCÍA-RUBIES & V. GRACIA. 1997b. Socio-behavioural context of reproduction in the Mediterranean dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe, 1834) (Pisces, Serranidae) in the Medes Islands Marine Reserve (NW Mediterranean, Spain). Scientia Marina 61 (1): 79-89. [ Links ]