Introduction

Tropical dry forests are highly-threatened neotropical ecosystems with a high diversity of species and a significant representation of endemic species (Bezaury, 2010; Ceballos, Martínez, García, Espinoza-Creel & Dirzo, 2010; Dirzo & Ceballos, 2010; Meave, Romero-Romero, Salas-Morales, Pérez-García & Gallardo-Cruz, 2012). They are characterized by a long dry season and by losing between 50% and 100% of the foliage during this season (Bezaury, 2010). For these reasons, this ecosystem has been considered a biodiversity hotspot (Olson & Dinerstein, 2002). Forests are widely distributed in Mexico, and they develop below 1200 meters above sea level (Bezaury, 2010). They occupy 16% of the territory of the State of Oaxaca, Mexico (Ortiz-Pérez, Hernández-Santana & Figueroa, 2004). In recent years, the original cover of dry forests has been reduced considerably; only 30% of its national coverage remains intact due to the advancement of agricultural and livestock frontiers, especially the overgrazing of cattle and goats (Trejo & Dirzo, 2000). In addition to this, Oaxaca State has few protected natural areas that conserve dry forests (Ceballos et al., 2010). These forests are found in the Balsas Depression, the Central Mountains and Valleys, the Depression of the Tehuantepec Isthmus and Tehuantepec Coastal Plain, and the Pacific Coastal Plain (PCP). All these regions are physiographic provinces of Oaxaca (Ortiz-Pérez et al., 2004).

The PCP of Oaxaca is characterized by its forest cover, mainly dry forest; however, it is also a highly deforested area, with only 2% of its cover in good condition (García, 2006). In this region, land use has changed from dry forest to crops and grasslands, which is one of the principal reasons why this area has been severely affected (Trejo, 2010). As with most regions of the world, the two main agents of anthropogenic changes are the expansion of large-scale commercial agriculture and increased urbanization. Despite the environmental disruption present in the area, only one investigation about herpetofaunal diversity has been done on the Central Coast of Oaxaca (García-Grajales, Buenrostro Silva & Mata Silva, 2016); such study recorded a total of 52 species that represented 11% of the herpetofauna of the state.

The amphibians is the most threatened group of terrestrial vertebrates with the highest extinction rate (Stuart et al., 2008), and in Mexico a little more than half of the amphibian species are in at some risk of extinction category, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2015). Meanwhile, reptiles play different roles in ecosystems, such as dispersing seeds, controlling insects’ populations -like ants or rodents’ populations-, and providing food for other animals (Cortés-Gómez, Ruíz-Agudelo, Valencia-Aguilar & Ladle, 2015).

In addition to the biological diversity represented, the PCP in Oaxaca also contains an extensive hydrological network, including the Colotepec River basin and the Yerbasanta hydrological micro-basin located within it. However, there is no information available on herpetofaunal diversity in the central region of the PCP. Therefore, in this research, richness of species, as well as composition and conservation status of herpetofauna in the Yerbasanta micro-basin on the Central Coast of Oaxaca are described.

Material and methods

Study site

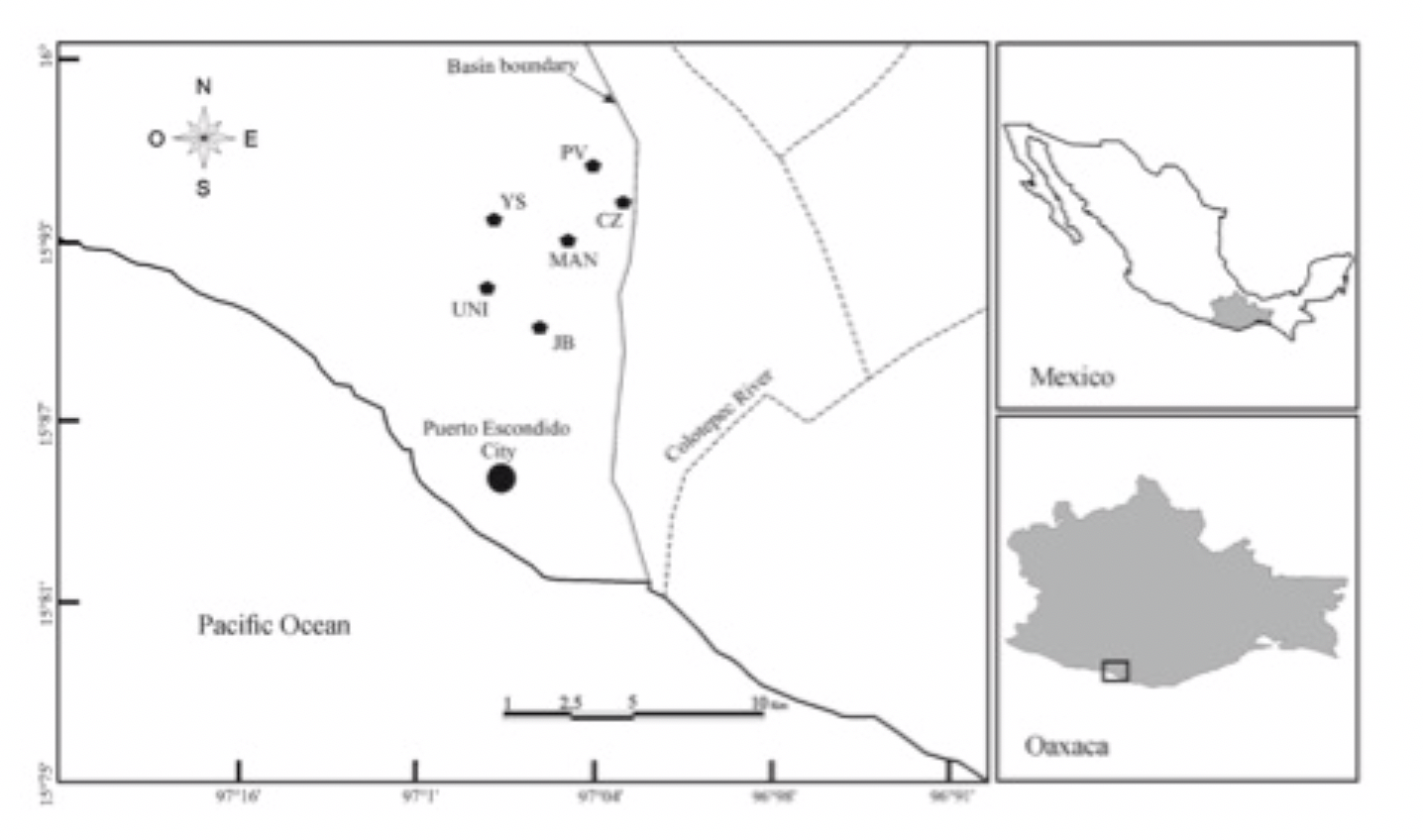

The study area is in Southern Oaxaca State, Mexico (15º 57’ and 15º 56’ N, and 97º 04’ and 97º 03’ W), between Colotepec River and the San José River hydrological basin, in the PCP physiographic sub-province (Figure 1). The PCP is characterized by an essential plain topography that presents a mountain axis (NW-SE direction), positioned perpendicular to the plain decline (Ortíz-Pérez et al., 2004). The climate is warm and sub-humid, with an annual mean temperature of 26.8 ºC and an annual mean precipitation of 2245 mm (García, 1973), and a long period of drought that goes from November to May (Trejo 2010). Deciduous tropical forest and shade coffee crops are the predominant land use and vegetation; however, semi-deciduous tropical forest is found in patches with reduced surface (Rzedowski, 1978; Torres-Colín, 2004). Some tree species in deciduous tropical forests are: Bursera excels (Kunth) Eng., B. simaruba (L.) Sarg., Ceiba parvifolia Rose, Lysiloma divaricata (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr. and Plumeria rubra L., with predominant species such as Acacia cochliacanta Willd., A. farnesiana (L.) Willd., A. cornígera (L.) Willd., Ziziphus amole (Sessé and Moc.), Guaiacum coulteri A. Gray, and Opuntia decumbens Salm-Dyck (Salas-Morales, Saynes-Vásquez & Schibli, 2003).

Source: Autor’s own elaboration.

Figure 1 Location of the Yerbasanta micro-basin, San Pedro Mixtepec Municipality, Oaxaca, México. Black pentagons represent the six localities under study (YS = Yerbasanta, CZ = Cerro Zopilote, MAN = Mandingas, UNI = Unión, PV = Pueblo Viejo, JB = Jardín Botánico).

For this research, the Yerbasanta micro-basin was divided into six localities (Yerbasanta, Pueblo Viejo, Jardín Botánico, Cerro del Zopilote, Mandingas, La Unión) according to their ecological characteristics and principal types of vegetation and land use. For example, Yerbasanta and Pueblo Viejo are characterized by the possession of riparian vegetation, while Jardín Botánico and Cerro del Zopilote present tropical dry forest, and Mandingas and La Unión present paddocks and grasslands.

Data collection

Sampling was carried out monthly between January and November 2010 during the dry season (January-May) and the rainy season (June-November). In each locality, about fifteen observation points were selected using stratified random sampling consisting of random walking rounds. During each monthly visit, surveys were conducted in the morning (07:00 h - 11:00 h) and in the afternoon (16:00 h - 19:00 h) for two consecutive days in each locality. Amphibians and reptiles were observed using the standard visual encountered surveys (VES) method by two observers for two hours (Doan, 2003; Heyer, Donelly, McDiarmid, Hayek & Foster, 1994;). For every captured amphibian and reptile, the date and duration of the survey, activity, substrate, species name and other supporting information were recorded; however, there was always the possibility of recatches because no marking system was used. Identification of species was conducted using special literature (Köhler, 2008; 2011; Lee, 2000). Taxonomic nomenclature was based on previous studies (Hynková, Starostová & Frinta, 2009; Köhler, Gómez, Petersen & Méndez de la Cruz, 2014). No specimens were collected after being identified and photographed; all specimens were released in the same area where they were caught. To identify the status of threat of species, the Norma Oficial Mexicana 059 (NOM-ECOL-SEMARNAT-059) (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2010) and the Red List of the IUCN (IUCN, 2015) were consulted.

Data analysis

The total species richness recorded in this research was compared with the total number of herpetofauna species in Oaxaca. The most represented orders, families, and species were determined.

In order to estimate the total species richness, species accumulation curves were plotted to assess completeness of the species inventory for each locality (local species richness) and per type of vegetation, using nonparametric estimators Chao 2 and Jackknife, which are based on presence estimates (Colwell, 2009; Hortal, Borges & Gaspar, 2006). To eliminate the effect of the order in which data was recorded, as well as to create accumulation curves (Jimenez-Valverde & Hortal, 2003), data was randomized 100 times in EstimateS (Colwell, 2009). The abundance of amphibians and reptiles was assessed with Whittaker or Rank-abundance curves (Feisinger, 2003; Moreno, 2001); therefore, species number and number of individuals per species from all localities were used. Curves were plotted according to the logarithm of the ratio for each species: p (n/N); and the data were sorted in relation to the most abundant and least abundant species (Feisinger, 2003).

The Shannon-Wiener diversity index (Heip & Engels, 1974) was calculated for each locality. Differences in species richness among localities were examined using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Colomba & Liang, 2011), and the t test modified by Hutcheson (Hutcheson, 1970) was used to examine differences in diversity between seasons.

Regional comparison of the herpetofauna composition was carried out using the Jaccard’s similarity index (Magurran, 2004), which works with presence-absence data. The index ranges from zero to one, where zero means no species are shared between the localities being compared, and one means that all species are found in both the sites.

To determine the category of endangered species, the list of Species at Risk published by the Mexican Ministry of the Environment, from the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (Diario Oficial de la Federación[DOF], 2010), and the Red List of the IUCN (IUCN, 2015) were consulted. The categories considered in the former source were Subject to special protection (Pr), Threatened (A) and Endangered (P). As for the latter source, the categories were Vulnerable, Endangered, and Critically Endangered. Finally, Mata-Silva’s (Mata-Silva, Johnson, Wilson & García-Padilla, 2015) environment vulnerability score (EVS) system has been followed to determine the conservation status of species.

Results

A total of five amphibian species and 37 reptiles species were recorded, belonging to 24 families and 40 genera. The amphibian and reptile orders represent 11.9% and 88.1% of the species in Oaxaca, respectively. The families Colubridae and Phrynosomatidae contain the greatest number of species (12 and three species, respectively), while Anolis and Sceloporus were the best represented genera in terms of species number (Table 1).

Table 1 List of amphibians and reptile species of Yerbasanta micro-basin, Oaxaca. The code of each species used in the curves of Rank-abundance (Code) is provided. Also, EM = endemic to Mexico, EO = Endemic to Oaxaca. NOM-059 = Mexican Official Standard Protection categories (Pr = Special protection, A = Endangered), IUCN = International Union for Conservation of Nature (LC = Leas Concern, DD = Deficient data, NC = Not considered) are provided. Value of environmental vulnerability index according to Wilson et al. (2013b) are shown.

| Order | Family | Specie | Endemism | NOM-059 | IUCN | EVS | Code |

| Anura | Bufonidae | Incilius marmoreus | EM | Pr | NE | 11 | 32 |

| Eleutherodactylidae | Eleutherodactylus pipilans | 11 | 33 | ||||

| Hylidae | Agalychnis dacnicolor | EM | Pr | NE | 13 | 11 | |

| Leptodactylidae | Leptodactylus melanonotus | LC | 6 | 25 | |||

| Ranidae | Lithobates forreri | Pr | NE | 3 | 28 | ||

| Squamata | Corytophanidae | Basiliscus vittatus | LC | 7 | 14 | ||

| Dactyloidae | Norops inmaculogularis | EO | Pr | LC | 16 | 6 | |

| Norops unilobatus | LC | 8 | 17 | ||||

| Phrynosomatidae | Sceloporus melanorhinus | LC | 9 | 18 | |||

| Sceloporus siniferus | LC | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Urosaurus bicarinatus | EM | LC | 12 | 2 | |||

| Teiidae | Aspidoscelis deppii | LC | 8 | 3 | |||

| Holcosus undulatus | NE | 7 | 4 | ||||

| Phyllodactylidae | Phyllodactylus tuberculosus | NE | 8 | 5 | |||

| Mabuyidae | Marisora brachypoda | NE | 6 | 31 | |||

| Sphenomorphidae | Sphenomorphus assatus | NE | 7 | 12 | |||

| Xantusiidae | Lepidophyma smithii | LC | 8 | 36 | |||

| Helodermatidae | Heloderma horridum | A | LC | 14 | 41 | ||

| Iguanidae | Ctenosaura pectinata | EM | A | DD | 15 | 16 | |

| Iguana iguana | Pr | NE | 12 | 29 | |||

| Boidae | Boa sigma | EM | A | NE | 10 | 38 | |

| Dipsadidae | Leptodeira maculata | LC | 7 | 35 | |||

| Coniophanes fissidens | LC | 7 | 37 | ||||

| Leptotyphlopidae | Epictia phenops | 4 | 9 | ||||

| Colubridae | Sthenorrina freminvilli | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Drymobius margaritiferus | NE | 6 | 15 | ||||

| Lampropeltis polyzona | EM | A | NE | 11 | 40 | ||

| Masticophis mentovarius | A | 6 | 19 | ||||

| Mastigodryas melanolomus | LC | 6 | 20 | ||||

| Drymarchon melanurus | LC | 6 | 21 | ||||

| Symphimus leucostomus | EM | Pr | LC | 14 | 22 | ||

| Trimorphodon biscutatus | 7 | 30 | |||||

| Salvadora Lemniscata | EM | Pr | LC | 15 | 10 | ||

| Senticolis triaspis | 6 | 39 | |||||

| Leptophis diplotropis | EM | A | LC | 14 | 24 | ||

| Oxybelis aeneus | NE | 5 | 23 | ||||

| Loxocemus bicolor | 4 | 7 | |||||

| Xenodontidae | Conophis vittatus | LC | 11 | 26 | |||

| Manolepis putnami | EM | LC | 13 | 13 | |||

| Elapidae | Micrurus browni | Pr | LC | 8 | 27 | ||

| Viperidae | Crotalus culminatus | EM | 15 | 42 | |||

| Kinosternidae | Kinosternon oaxacae | EM | Pr | 14 | 34 |

Source: Autor’s own elaboration.

The highest number of amphibian and reptile species was found in Pueblo Viejo (22 species), followed by Yerbasanta and Jardín Botánico (21 species each), Cerro Zopilote and Mandingas (20 species, respectively), and Unión (16 species). With respect to the type of vegetation and land use, riparian vegetation and deciduous tropical forest were recorded with the largest number of species (27 and 26, respectively), followed by paddocks (23 species).

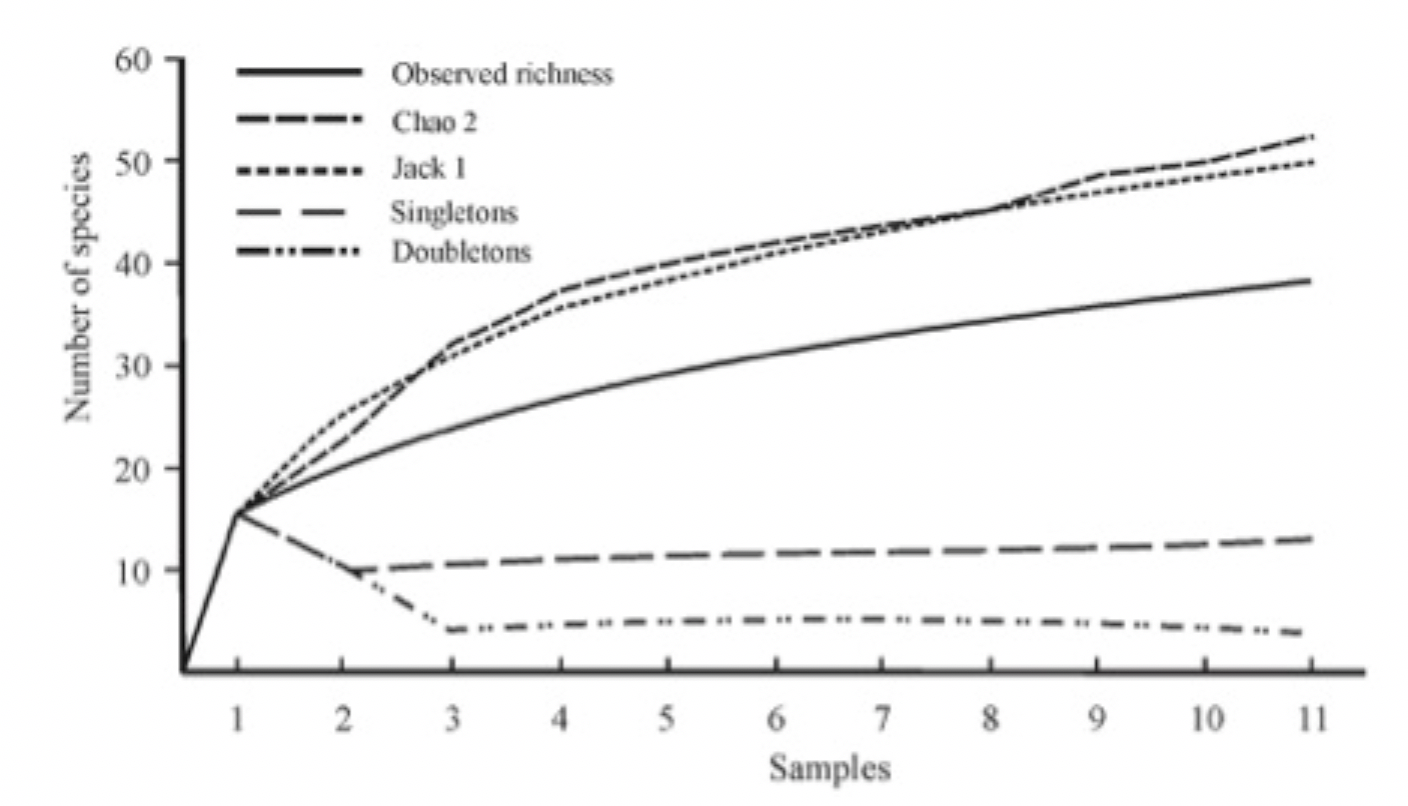

Species accumulation curves according to Chao 2 and Jackknife estimators predicted an asymptote in 52 and 50 species, respectively, for the micro-basin; thus, in this research’s survey, this meant that 75% of the estimated total richness was recorded (Figure 2). Per types of vegetation, the riparian vegetation reached a representativity of 73%, while deciduous tropical forest reached a completeness of 85%, and paddocks obtained a representativeness of 81%.

Source: Autor’s own elaboration.

Figure 2 Species-accumulation curve for amphibians and reptiles in the Yerbasanta micro-basin, Oaxaca.

The pattern of abundance of amphibians and reptiles was relatively similar between the seasons for the whole micro-basin. For both seasons, Sceloporus siniferus, Aspidoscelis deppii, and Anolis immaculogularis were the dominant species. The rarest species were Leptodeira maculata, Lepidophyma smithii, Conophis vittatus, Manolepis putnami, and Micrurus browni, for both seasons.

Regarding the herpetofaunal diversity index found in the micro-basin, Pueblo Viejo showed the highest value of diversity (H´ = 2.45), followed by Unión (H´ = 1.86), while the remainder had lower values. Statistical tests revealed that there were significant differences in species richness (Kruskal Wallis, H = 6.77; p < 0.05; df = 3) among locations. The species richness (mean rank = 31.65) in Pueblo Viejo differed from the other locations. As for diversity between seasons, the rainy season had a higher diversity (H´ = 1.9) than the dry season (H´ = 1.70), but there were no significant differences (Hutcheson t: 5.14; g.l. 2600; p > 0.05).

The similarity analysis reveals that Pueblo Viejo and Mandingas (Jaccard index = 0.68), Mandingas and Yerbasanta (Jaccard index = 0.64), and Pueblo Viejo and Yerbasanta (Jaccard index = 0.59) are most similar in species composition, sharing around 68%, 64% and 59% of its species, respectively. Unión and Jardín Botánico were the least similar locations (Jaccard index = 0.37).

Only 14 out of 42 species recorded in the micro-basin are in a category of risk according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (DOF, 2010). Heloderma horridum, Boa sigma, Ctenosaura pectinata, and Leptophis diplotropis are listed as threatened, while Lithobates forreri, Anolis immaculogularis, Iguana iguana, Lepidophyma smithii, Loxocemus bicolor, Salvadora lemniscata, Symphimus leucostomus, Micrurus browni, and Leptodeira maculata are listed as endangered. Twenty other species are listed as a lower concern according to IUCN’s Red List, and the rest of the species are listed as not evaluated or insufficient data.

According to EVS, 22 species are considered to have a low level of vulnerability, 12 species are of average level of vulnerability, and eight species are considered to have a high level of vulnerability. In this research, 13 species of importance were recorded, 12 of which are endemic to Mexico and one (Anolis immaculogularis) endemic to Oaxaca.

Discussion

In the present study, 42 amphibian and reptiles species were recorded in the Yerbasanta micro-basin on the Central Coast of Oaxaca, representing 41% of the species in the Planicie Costera del Pacífico sub-province (Mata-Silva et al., 2015), as well as 9.5% of amphibian and reptile species richness in Oaxaca (442 species) (Mata-Silva et al., 2015) and 3.49% of species richness of Mexico (1203 species) (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014; Parra-Olea, Flores-Villea & Mendoza 2014). Oaxaca state is considered the entity with the greatest amphibian and reptile diversity in Mexico (Mata-Silva et al., 2015); however, studies about these vertebrates have focused mostly on northeastern and eastern parts of the state (Casas-Andreu, Méndez de la Cruz & Aguilar-Miguel, 2004). Therefore, little information exists for the Sierra Madre del Sur and PCP sub-provinces. For that reason, this work provides important information about the diversity of herpetofauna on the Planicie Costera del Pacífico sub-province, highlighting the importance of the micro-basin with regards to the regional herpetofaunal richness.

Although the richness species in Mexico may vary from latitudinal, altitudinal and even vegetation situations as product of the topographic and physiographic complexity of its landscapes (Wilson, Mata-Silva & Johnson 2013a; Wilson, Johnson & Mata-Silva, 2013b), this has been used as an indicator of biodiversity in mainland environments (Hortal, Trinatis, Meiri, Théubault & Sfenthourakis, 2009) and for understanding the comparisons among communities (Gotelli & Chao, 2013). However, there are several regions whose inventories of species remain incomplete (Whittaker & Fernández, 2010). Due to the absence of herpetofauna inventories near this study area, comparisons have been made with the nearest locations possible. The herpetofaunal richness recorded in this study is less than that of Parque Nacional Lagunas de Chacahua (52 species) (García-Grajales et al., 2016), located in the same sub-province, and that of the Nizanda region (59 species) (Barreto-Oble, 2000), located in the Tehuantepec Isthmus sub-province. However, there is a similar richness in Pluma Hidalgo (44 species) (Caviedes-Solís, 2009), located in South Sierra sub-province, and in Cerro Guiengola (40 species) (Martín-Regalado, González-Ugalde & Cisneros-Palacios, 2011), located in the Tehuantepec Isthmus. Nevertheless, this study showed that species richness is higher in this study’s sites than in other similar sites in Mexico, such as Reserva de la Biósfera Barranca de Metztitlán, Hidalgo (11 species) (Vite-Silva, Ramírez-Bautista & Hernández-Salinas, 2010) and Huetamo, Michoacán (Reyna-Álvarez, Suazo-Orduño & Alvarado-Díaz, 2010).

Based on the index of species diversity, paddocks (Mandingas and Unión) had a slightly smaller diversity index compared to riparian vegetation or deciduous tropical forest, due to these areas having highly modified landscapes (i.e. settlements and paddocks) and containing little remnant vegetation (McIntyre & Hobbs, 1999), thus, having limited resources. Moreover, tropical deciduous forests are sites that function like small islands. Riparian vegetation keeps the heterogeneity of the ecosystem functioning as a buffer and connection between different areas (García & Cabrera, 2008), and it also provides places of refuge for numerous species of fauna (Suazo-Orduño, Alvarado-Díaz & Martínez-Ramos, 2011); therefore, it contains considerable species diversity.

According to Chao 2 and Jackknife estimators, the species accumulation curve reached 75% of the intended species, and unique and duplicate algorithms did not show a tendency to overlap, proving that the inventory is not complete. Although specific criteria have not been established to determine whether an inventory is complete or not, most occasions often establish arbitrary limits such as the fact that over 80% of the estimate of richness species is an acceptable value (Jiménez-Valverde & Hortal, 2003). One of the reasons is probably the type of sampling (only diurnal) and the different activity patterns of any arboreal, nocturnal or fossorial species (Petersen & Meier, 2003). With respect to rare species, most were species of snakes. The snakes are more difficult to observe and locate due to their discrete and elusive habits. However, the abundance of a species tends to change while increase the sampling effort or different sampling methods are used to complement direct search (Urbina-Cardona & Reynoso, 2005). For this situation, Sorensen, Coddington & Scharff (2002) recommend focusing sampling effort on a few families or guilds, developing specific protocols to minimize the problems of rare species.

The species composition in the Yerbasanta micro-basin is characterized by a considerable number of species with little abundance and a low number of species with high relative abundance, but it can be considered as generalist species (García & Cabrera, 2008). According to one study (Gillespie, Howard, Lockie, Scroggie & Boeadi, 2005), generalist species are capable of using unlimited elements and non-specific habitats, and their abundance tends to increase in disturbed areas and will continue to increase due to lack of competitors; therefore, there is an increase of space and opportunity to grow (Jonsen & Fahrig, 1997).

The results in this study show that a marked seasonality effect does not exist in the species composition, probably because in both periods the environmental conditions are homogeneous between the sites, causing the species to be distributed homogeneously (Ríos-López & Mitchell, 2007). Inside the micro-basin, there are critical components that provide ideal ecological conditions for food processes, refuge, thermoregulation, resources that provide energy and the permanence of vegetation, as well as bodies of water. These factors influence the presence of the species in both seasons (Urbina-Cardona & Reynoso, 2005).

Twelve out of the 42 species of amphibians and reptiles found in this study are endemic to Mexico, and one species is endemic to Oaxaca, all of which are listed under the species at risk of extinction category by the Mexican Ministry of Environment. This underscores the need to secure the protection of these and other sites along the Central Pacific Coast of Oaxaca. Based on our results, the herpetofaunal diversity in paddocks seems to be rather low, even though tropical deciduous forest and riparian vegetation are fairly common to the paddocks, and together they present similar diversity to adjacent areas, such as Parque Nacional Lagunas de Chacahua (García-Grajales et al., 2016).

The number of amphibian and reptile species that inhabit the Yerbasanta micro-basin is considerably high; therefore, it suggests that, as altered habitats, they can maintain a significant number of species of fauna. The contribution of this work, in addition to other studies (García-Grajales et al., 2016), represents this baseline information found in the PCP province. On the other hand, due to the species richness recorded and estimated here, the Coast of Oaxaca should be considered in conservation policies, particularly because this region is under hard pressure due to change in land use (Salas-Morales & Casariego-Madorell, 2010). The promotion of voluntary areas for conservation as local initiatives, under the program of Áreas Certificadas para la Conservación, would probably slow down the threats of deforestation of the tropical deciduous forest on the Coast of Oaxaca (Ortega et al., 2010; Salas-Morales & Casariego-Madorell, 2010); therefore, this program could benefit the survival of species, mainly those that are endemic to Mexico and/or are nationally threatened.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)