Introduction

Essential oils (EO) are an interesting group of substances obtained from plant material; almost exclusively from flowers, leaves, barks, woods, roots, rhizomes, fruits and seeds (Burt, 2004; Celiktas et al., 2006). Generally, EO are liquids although they exhibit an oily consistency with an aromatic and pleasant odor (Bassolé & Juliani, 2012). Chemically, EO are a complex and highly variable mixture of constituents appertaining to different groups such as terpenes and aliphatic compounds with antibacterial and antifungal properties (Carmo, de Oliveira Lima & de Souza, 2008; Delamare, Moschen-Pistorello, Artico, Atti-Serafini & Echeverrigaray, 2007; Pichersky, Noel & Dudareva, 2006).

Food safety represents a major problem, especially in the low-income countries, which affects hundreds of millions of people as a consequence of the increment in the incidence of food-borne diseases. With the purpose of achieving an accurate shelf life, a great number of food products require protection against spoilage during the stages of: i) preparation, ii) storage and iii) distribution (World Health Organization [WHO], 2007). Another major problem is due to the ability of microorganisms to survive in food, causing spoilage and quality deterioration (Jacob, Mathiasen & Powell, 2010). The development of food preservation methods arises from the necessity of extending the shelf life and improves the storage conditions. Alternative methods to synthetic chemical preservatives include non-thermal inactivation technologies: radiation, high pressure, pulsed electric fields, modified atmosphere, biopreservation and antimicrobial compounds derived from plants (Devlieghere, Vermeiren & Debevere, 2004).

The food and pharmaceutical industries have shown great interest towards antimicrobial properties of EO, since the use of natural additives seems to be effective for replacing synthetic preservatives (Das, Tiwari & Shrivastava, 2010). Frequently, these natural compounds are in demand because they are eco-friendly, degradable, free of side effects and cheaper than chemical preservatives. Nevertheless, it has been assessed that EO antimicrobial activity derived from plants of the same species could be extremely different. These differences could be related to geographical growing regions, harvest time, genotype and weather conditions. For this reason, EO biological activity obtained from plants, grown in a determined region, requires characterization (Oussalah, Caillet, Saucier & Lacroix, 2007). Oregano has been found to possess antimicrobial activity, which may have beneficial applications in food. However, a major effect of the oil use in food is related to the sensorial modification of taste. A number of studies have focused on the synergistic activity of EO combinations in order to reduce the negative sensory impact and to obtain an effective antimicrobial activity (Fu et al., 2006; Gutierrez, Barry-Ryan & Bourke, 2009). Other researchers are mainly focused on EO synergic effect in combination with other natural antibacterial compounds (Solomakos, Govaris, Koidis & Botsoglou, 2008). The combination oregano-ascorbic acid has been used to avoid deterioration of meat quality and as diet supplement, but its effect on microbial growth has not been explored (Ghazi, Amiadian & Norouzi, 2015; Young, Stagsted, Jensen, Karlsson & Henckel, 2003). Therefore, the present study deals with the evaluation of certain commercial EO and chemical preservatives against pathogenic microorganisms. The primary aim of this work is to evaluate the synergic and viability effects of oregano oil in combination with ascorbic acid.

Materials and methods

Source of essential oils

Fourteen commercial EO including laurel (91028), onion (10005), Mexican lemon 1 (91027), Mexican lemon 2 (91031), cumin (91018), black pepper (91048), orange 5VC (91155), ginger (91026), sweet orange (91041), commercial oregano 296 (10053), garlic (10000), grapefruit (91064), lemon (10009) and rosemary (91053) were purchased by Aceites-Essencefleur, Flavor’s Division (http://www.essencefleur.com).

Microbial inocula

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Candida albicans was supplied by the National Culture Collection, CINVESTAV-IPN, México. Bacterial cultures were maintained at 4 °C on Nutrient Agar (NA) and yeast on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar slants (SDA). Bacterial inocula were prepared on Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth in order to achieve 1 × 106 CFU ⋅ ml-1. For yeast, the inoculum was prepared by diluting an overnight culture with Sabouraud Dextrose broth until it reached 1 × 106 CFU ⋅ ml-1 (Oliva et al., 2010).

Antimicrobial screening of EO by disc diffusion method

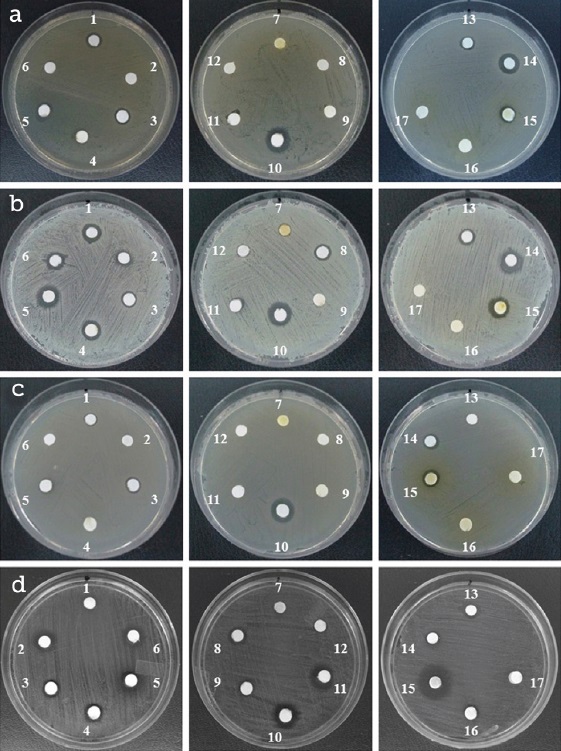

A preliminary screening to select EO with antimicrobial activities was accomplished by Disc Diffusion Method (Carović-Stanko et al., 2010). The adequate solidified media (MH agar for bacterial strains and SDA for C. albicans) were seeded with 0.1 ml of inoculum suspension at 106 CFU ⋅ ml-1 spreader over the plates. Thereupon, sterile paper discs of 6 mm diameter (Whatman No. 1) soaked with 5 μl of pure commercial EO were placed on the media surface. The dishes were kept at 37 °C/24 h for bacteria and 29 °C/48 h for yeast. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured with a calliper. An inhibitory scale for EO was determined as follows: > 15 mm zone of inhibition was strongly inhibitory; 10 mm - 15 mm zone of inhibition was moderately inhibitory, and < 10 mm was not inhibitory (Figure 1).

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Figure 1 Antimicrobial screening of plant essential oils against microbial pathogens by the disc diffusion method. Panel A, Escherichia coli; panel B, Staphylococcus aureus; panel C Salmonella ser. Typhimurium; panel D, Candida albicans. Oils: 1, laurel; 2, onion; 3, mexican lemon 1; 4, mexican lemon 2; 5, cumin; 6, black pepper; 7, orange SVC; 8, ginger; 9, sweet orange; 10, commercial oregano; 11, garlic; 12, grapefruit; 13, lemon; 14, rosemary; 15, concentrated phenol citric extract I; 16, concentrated phenol citric extract II; 17, concentrated phenol citric extract III.

A modified disc-diffusion method to evaluate selected essential oils was implemented. Briefly, EO solutions were diluted in 100% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations ranges of 3 μg ⋅ ml-1, 5 μg ⋅ ml-1, 7 μg ⋅ ml-1, and 10 μg ⋅ ml-1. DMSO, a non-toxic dispersing solvent was used to increase diffusion of oils onto the agar Petri plates. Solutions were kept in amber glass vials at ± 4 °C as stock solution. Sterile paper discs were soaked with 10 μL of diluted oils and placed on the inoculated media with the corresponding microorganisms, as described previously. Paper disc moistened w ith 10 μl of 100% DMSO was used as negative control. The Petri plates were incubated, and diameters of the inhibition were measured as mentioned above. Kanamycin and itraconazole were positive controls for bacteria and yeast, respectively (data not shown; stock solutions at 200 μg ⋅ ml-1 and 500 μg ⋅ ml-1, respectively). The assays were carried out in triplicate.

Inhibitory and lethal concentrations of EO and food preservatives by micro-dilution test

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) and Minimum Lethal Concentrations (MLC) tests were accomplished by micro-dilution method using 96-well microtitre plates. Solutions of 5% (v/v) EO (oregano, laurel, cumin and rosemary) were prepared with DMSO. The 96-well plates were arranged dispersing 100 μl of 2 X MH broth for bacteria or 2X SDB for yeast; afterwards, 100 μl of EO solution was added to the first wells and two-fold serial dilutions were performed to obtain a concentration range from 0.1% to 1.25% (v/v). In addition, 100 μl of the bacteria or yeast inocula were added to the wells and mixed, and microplates were incubated at adequate temperatures for 24 h or 48 h. The MIC were determined after adding 10 μl per well of 20 mg ⋅ ml-1 TTC (2, 3, 5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride, Sigma-Aldrich) incubated under the appropriate conditions for at least 3 h in darkness (Sartoratto et al., 2004). The MLC was determined by serial sub-cultivations of 2 μl from MIC wells in micro plates containing 100 μl of broth + 10 μl of 20 mg ⋅ ml-1 TTC per well. Micro plates were further incubated for 24 h. The lowest concentration showing no visible colour was defined as the MLC, indicating 99.5% of the original inocula killing. The study determined the MIC and MLC concentrations of conventional preservatives used in food products. Stock solutions showed the following values: 3% (w/v) sodium benzoate, 8% (w/v) ascorbic acid (Asc), commercial vinegar, and 12% (v/v) acetic acid (AcA). Finally, MIC and MLC values of the combination of OrO with AcA or Asc to inhibit the microbial growth was evaluated by the 96-well micro-dilution method, as mentioned above. In order to obtain the combinations, MIC obtained from the individual test were used to mix the compounds in a range of concentrations from 2% to 0.125%. MIC and MLC values were obtained from two independent experiments with two replicates.

Checkerboard test and time-kill curves

Checkerboard experiments and time-kill curves were performed using 96-well microtiter plates with the purpose of evaluating and quantifying the antimicrobial activity of oregano oil and their combinations with acetic acid and ascorbic acid (Marchetti, Moreillon, Glauser, Bille & Sanglard, 2000).

-

Checkerboard microtiter plate testing. The micro plates were arranged distributing 50 μl 2 X MH broth for bacteria or 2X SDB yeast into each well. After this, 50 μl of oregano oil was twofold diluted along the x-axis, and 50 μl of AcA or Asc were twofold diluted along the y-axis to give a final volumen in each well of 100 μl. An equal volume of cells suspension containing 106 CFU ml-1 of the tested microorganism was added to each well. Then, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h or 29 °C for 48 h under aerobic conditions. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) was calculated as follows: FICI = FICA + FICB; where: FICA = MIC of OrO in combination with AcA or Asc/MIC of OrO alone (MIC-AB/MIC-A), and FICB = MIC of AcA or Asc in combination with OrO/MIC of AcA or Asc alone (MIC-BA/MIC-B).

The results were interpreted as follows: synergy (FICI <0.5), addition (FICI >0.5 and ≤1.0), indifference (FICI >1.0 and ≤4.0) or antagonism (FICI >4.0).

Time-kill assays. For bacteria, a loopful of cells from a single colony grown on MH agar Petri plates was transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask with 50 ml of MH broth. These cultures were maintained at 37 °C/ 150 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.5-0.6. Afterwards, 25 ml of the culture were transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask and mixed with solutions of Asc, OrO and the combination OrO + Asc equivalent to ½ MIC (0.25%), 2 MIC (0.16%) and ½ + 2 MIC (0.25% + 0.16%), respectively. The optical density was registered at predetermined time points (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 24). The effect of each treatment regarding the cell viability was assessed by sub-culturing 10 μl of each culture, into a 24-well plate containing 2 ml of MH medium (per well) and TTC (final concentration of 0.001%). Micro plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and it was possible to record a visible color. Each experiment included growth control in the absence of ascorbic acid or essential oil. Assays were conducted in triplicate. Time-kill curves were constructed by plotting optical density against time (h). Experiments for C. albicans were conducted in the same way, except that culture medium was SDA and SD-broth (at 29 °C).

Statistical Analysis

The data related to inhibition by the disc diffusion assays were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Means were compared using an Analysis of Variance (Anova) followed by LSD testing at p = 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed through Stat Graphics Centurion version XV V16.2.04 (Stat point Technologies, Inc).

Results and discussion

Selection of plant essential oils with antimicrobial activity

This study evaluated the in vitro antimicrobial activity of several commercial essential oils from aromatic plants and four preservatives usually employed in food industries. Table 1 summarizes the antimicrobial activity of the EO against pathogenic microorganisms. It is observed that laurel, cumin, oregano, and rosemary oils exhibited inhibitory activity against the four pathogens tested. S. aureus, E. coli and Salmonella ser. Typhimurium were susceptible to 7, 6 and 5 EO, respectively, while C. albicans was the most sensitive pathogen to plant oils. Also, it is shown that OrO exhibited the highest inhibition diameter zone. The statistical analysis confirmed the above results (p = 0.05). Several studies have shown inhibitory effects of EO on Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Lemon, orange and rosemary EO inhibited the growth of S. aureus and E. coli, while oregano demonstrated to be extremely active against E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus and Salmonella ser. Typhimurium (Di Pasqua, De Feo, Villani & Mauriello, 2005; Elgayyar, Draughon, Golden & Mount, 2001; Prabuseenivasan, Jayakumar & Ignacimuthu, 2006). Other studies demonstrated significant inhibitory activity on Fluconazole-resistant Candida species (Rabadia, Kamat & Kamat D., 2001). In this study, the most susceptible pathogen to the EO was S. aureus as indicated in other works (Delaquis, Stanich, Girard & Mazza, 2002).

Table 1 Antimicrobial activity of plant essential oils

| EO | Inhibition zone diameter† (mm ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Salmonella ser. Typhimurium |

S. aureus | C. albicans | |

| Laurel | 9.1 ± 0.9c | 7.7 ± 0.4b | 11.0 ± 0.7c | 8.7 ± 0.3c |

| Onion | 0a | 7.8 ± 0.6b | 8.0 ± 0.5b | 10.7 ± 0.5d |

| Mexican lemon 1 | 8.4 ± 0.5b | 0a | 7.8 ± 0.3b | 8.1 ± 0.5c |

| Mexican lemon 2 | 0a | 0a | 8.9 ± 0.3b | 8.7 ± 0.6c |

| Cumin | 9.9 ± 0.1d | 8.2 ± 1.2b | 12.8 ± 0.7c | 10.4 ± 0.3d |

| Black pepper | 0a | 0a | 10.6 ± 1.0c | 10.1 ± 0.3d |

| Orange SVC | 0a | 0a | 7.3 ± 0.3b | 0a |

| Ginger | 0a | 0a | 7.9 ± 0.6b | 8.5 ± 0.6c |

| Sweet orange | 0a | 0a | 0a | 6.4 ± 0.3b |

| Commercial oregano | 12.6 ± 0.7f | 11.6 ± 0.4c | 13.0 ± 2.0c | 9.9 ± 0.3d |

| Garlic | 0a | 0a | 0a | 11.5 ± 0.9e |

| Grapefruit | 0a | 0a | 0a | 6.6 ± 0.2b |

| Lemon | 8.3 ± 0.7b | 0a | 10.7 ± 1.0c | 8.9 ± 0.4c |

| Rosemary | 11.7 ± 0.1e | 8.2 ± 0.7b | 11.8 ± 1.7c | 7.8 ± 0.5c |

| Kanamycin (30 mg) | 19.9 ± 0.1g | 19.9 ± 0.1g | 19.9 ± 0.1g | ND |

| Itraconazole (30 mg) | ND | ND | ND | 10.2 ± 0.5d |

†Different letters are significantly different (p = 0.05). Zero, no inhibition. ND, not determined. No inhibitory effect on microorganisms’ growth were detected with 100% DMSO.

Source: Author's own elaboration.

To avoid the irregular distribution of oils into the culture medium derived from their water insolubility, hydrophobic nature and high viscosity, a dispersant agent as solubilizing agent was selected. DMSO was used to prepare laurel, cumin, oregano and rosemary solutions at concentrations from 3 mg ⋅ ml-1 to 10 mg ⋅ ml-1. Table 2 showed that oregano exerted the highest inhibitory effect with an inhibition diameter of more than 16 mm on E. coli, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and C. albicans. In turn, rosemary oil inhibited E. coli and S. aureus cells in the same proportion. The study confirms that S aureus is the most susceptible microorganism regarding EO. These results showed that DMSO improve the activity of oils in water based-media increasing their inhibitory activity.

Table 2 Effect of different concentrations of selected EO on the growth of pathogenic microorganisms*

| EO (μg) | Laurel | Cumin | Oregano | Rosemary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||||

| 30 | 9.0 ± 0.3a | 9.1 ± 0.4a | 12.4 ± 1.1a | 10.3 ± 0.6a |

| 50 | 9.7 ± 0.4a | 10.7 ± 0.3b | 17.2 ± 1.8b | 13.0 ± 0.7b |

| 70 | 10.7 ± 0.5b | 11.9 ± 0.9b | 20.9 ± 3.6c | 14.1 ± 0.5c |

| 100 | 12.6 ± 0.9c | 13.4 ± 1.1c | 19.7 ± 1.2c | 16.1 ± 0.8d |

| Salmonella ser. Typhimurium | ||||

| 30 | 9.3 ± 0.7a | 8.3 ± 0.7a | 10.4 ± 0.4a | 9.2 ± 0.1a |

| 50 | 9.7 ± 0.3a | 9.2 ± 0.5a | 11.2 ± 0.2a | 10.3 ± 0.6a |

| 70 | 10.6 ± 0.4a | 10.1 ± 0.4a | 13.3 ± 0.5b | 13.6 ± 0.4b |

| 100 | 11.7 ± 0.8b | 12.0 ± 1.0b | 16.4 ± 0.9c | 12.4 ± 0.2b |

| S. aureus | ||||

| 30 | 10.9 ± 1.0a | 8.6 ± 0.2a | 12.2 ± 1.0a | 9.6 ± 1.2a |

| 50 | 13.0 ± 0.6b | 11.8 ± 0.3b | 15.0 ± 2.2b | 11.8 ± 1.0b |

| 70 | 14.5 ± 0.4b | 23.2 ± 1.6c | 11.9 ± 0.3a | 14.3 ± 1.2c |

| 100 | 26.6 ± 1.7c | 25.6 ± 1.5d | 16.1 ± 1.1b | 17.0 ± 1.1d |

| C. albicans | ||||

| 30 | 10.6 ± 0.3a | 9.4 ± 0.3a | 15.0 ± 0.3a | 8.4 ± 0.4a |

| 50 | 11.5 ± 0.3a | 10.4 ± 0.5a | 17.3 ± 0.7b | 8.8 ± 0.6a |

| 70 | 13.0 ± 0.7b | 10.7 ± 0.6a | 17.1 ± 0.9b | 12.1 ± 0.8b |

| 100 | 14.9 ± 0.8c | 11.2 ± 0.4b | 17.2 ± 0.5b | 12.7 ± 0.4b |

*Mean of three replicates (± SD). Statistical differences were calculated for each microorganism, wherein means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). No inhibitory activity was detected with paper disc soaked with 100% DMSO.

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Determination of MIC and MLC values for the inhibition of microbial pathogens

The MIC and MLC values of laurel, cumin, oregano, and rosemary EO were calculated considering their inhibitory activity against the pathogens (Table 3). Additionally, MIC and MLC concentrations for some food preservatives were also obtained. Based on the metabolic activity on TTC, the MIC showed the lowest concentration where no visible microbial growth was detected, and the MLC showed the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent to be lethal to a particular microbe. The analysis demonstrated that the most efficient inhibitory oil against the pathogenic microorganisms was oregano with a MIC value of 0.078% (v/v), followed by cumin (0.313%, v/v), and rosemary (0.313% to 0.625%, (v/v). In accordance to this, the MLC of EO was extremely close to the MIC, indicating a good lethal activity against the pathogens tested. A previous study showed a strong antibacterial activity for oregano and rosemary on E. coli and S. aureus at concentrations of about 0.125% to 5% (w/v), while cumin needed higher concentrations to exert antimicrobial effects (> 4%, w/v) (Witkowska, Hickey, Alonso-Gomez & Wilkinson, 2013). Oregano oil presented similar MIC-MLC values (0.5-1.0% v/v) against S. aureus, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, and E. coli, according to previous studies (Soković, Marin, Brkić & Van Griensven, 2007). Variations to antimicrobial activities detected in the EO could be attributed to the different chemical composition as a consequence to the existence of a diversity of conditions attributable to plant subspecies, different agro-climatic conditions for plant breeding, plant maturity stage, and particular distillation conditions to obtain the oils (Anwar, Hussain, Sherazi & Bhanger, 2009).

Table 3 MIC and MLC values of EO and some food preservatives on pathogenic microorganisms†

| E. coli |

Salmonella ser. Typhimurium |

S. aureus | C. albicans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC /MLC | MIC/ MLC | MIC/MLC | MIC/MLC | |

| EO | ||||

| Oregano | 0.313/0.313 | 0.313/0.313 | 0.156/0.313 | 0.313/0.625 |

| Cumin | 0.313/0.313 | 0.313/1.25 | 0.313/0.313 | 0.313/0.625 |

| Laurel | 0.625/0.625 | 0.625/0.625 | 0.625/0.625 | 0.625/1.25 |

| Rosemary | 0.625/0.625 | 0.313/0.313 | 0.625/0.625 | 0.313/0.625 |

| Food preservatives | ||||

| Acetic acid (AcA) | 0.1/0.1 | 0.1/- | 0.1/0.1 | -/- |

| Ascorbic acid (Asc) | 0.75/2 | 1/- | 0.5/2 | 1/- |

| Sodium benzoate | 0.75/- | 0.75/- | 0.75/- | -/- |

| Vinegar | 0.313/1.25 | 0.625/1.25 | 0.313/0.625 | 1.25/2.5 |

| Combination | ||||

| OrO:AcA | 0.156:0.1/0.156:0.1 | 0.156:0.1/0.313:0.2 | 0.078:0.1/0.078:0.1 | 0.156:0.1/0.313:0.1 |

| OrO:Asc | 0.156:0.1/0.156:1 | 0.313:1/0.313:1 | 0.156:1/0.156:1 | 0.313:1/0.313:1 |

†Concentration in% (v/v for EO, vinegar and acetic acid; w/v for sodium benzoate and ascorbic acid). (-) No inhibitory or lethal effect.

No inhibitory effect on microorganisms’ growth were detected with 100% DMSO.

Source: Author's own elaboration.

The mechanism of antibiosis of the extracts was calculated using the ratio of MLC/MIC (Okeleye, Mkwetshana & Ndip, 2013). An index ratio of ≤ 2 observed for oregano, cumin, laurel, and rosemary suggested a bactericidal/fungicidal mechanism to inhibit the growth of the pathogens evaluated (Table 4). The only exception was obtained for cumin on S. Typhimurium with an activity ratio of 4.0.

Table 4 FIC indices of oregano oil combined with acetic and ascorbic acids †

| Combination | E. coli |

Salmonella ser. Typhimurium |

S. aureus | C. albicans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIC | FICI | FIC | FICI | FIC | FICI | FIC | FICI | |

| OrO:AcA | 0.49 | 0.99 (A)¥ | 0.5 | 1 (I) | 1 | 2 (I) | 0.49 | 0.99 (A) |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||

| OrO:Asc | 1 | 2 (I) | 0.5 | 0.75 (A) | 1 | 2 (I) | 0.48 | 0.98 (A) |

| 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||

†Results are means of three different experiments. ¥ The results were interpreted as: synergistic (S, FICI < 0.5), additive (A, FICI > 0.5 and ≤ 1.0), indifferent (I, FICI > 1 and ≤ 4), or antagonistic (AN, FICI > 4).

Source: Author's own elaboration.

In relation with the antimicrobial evaluations for common food preservatives, the MIC values obtained for Asc ranged from 0.5% to 1%, lower in comparison to the results reported by Zhang, Wakisaka, Maeda & Yamamoto (1997); e.g. a higher concentration of ascorbic acid was required to inhibit E. coli growth (> 1.6% w/v). Commercial vinegar was effective against all microorganisms in concentrations ranging from 0.313% to 1.25% (v/v), but C. albicans was the most resistant pathogen. A previous study presented similar results wherein the MIC value of 0.1% to 0.2% (v/v) was effective against S. aureus, S. epidermidis, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli (Lang, 2013). Sodium benzoate preservative exerted a bacteriostatic activity against E. coli and Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and bactericidal over S. aureus; C. albicans was not affected by the compound. It is worth mentioning that in previous works a strong anticandidal activity at a concentration of 0.25% (2.5 mg/ml) was obtained (Stanojevic, Comic, Stefanovic & Solujic-Sukdolak, 2009).

It was found that AcA showed the lowest MIC value (0.1%) in relation to the other preservatives with concentrations previously reported (Pundir & Jain, 2011).

Synergic and viability evaluation of the combinations of oregano oil and conventional preservatives

Previous results showed that EO present high efficiency against the tested pathogens, particularly in the case of oregano oil. Notwithstanding, a higher concentration of essential oil is required to achieve the same effect in food (Burt, 2004). This action can alter the organoleptic properties of food, modifying the food taste or exceed the acceptable flavor thresholds (Hsieh, Mau & Huang, 2001). Combinations of plant essential oils can help to reduce the concentrations and, as a consequence, to reduce the sensory impact. In the light of the foregoing, the current research was extended to evaluate the effect of OrO in combination with Asc and AcA to inhibit the microbial growth. Table 4 shows that OrO presents greater efficacy in combination with acidificants; MIC and MLC values were dropped by a half, being more efficient with AcA.

The quantitative effects of oregano in combination with acidic preservatives (AcA or Asc) were determined by the checkerboard test in terms of FIC indexes (FICI). Results show that none of these combinations demonstrated synergistic activity against E. coli, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, S. aureus, and C. albicans (Table 4). The OrO + AcA combination showed an additive effect on E. coli and C. albicans, but it was indifferent against Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and S. aureus. In contrast, the OrO + Asc combination exhibited an additive effect over Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and C. albicans, and indifferent for E. coli and S. aureus. No antagonistic activity was observed between the combinations evaluated. MIC values for these combinations resulted in the following way: OrO + AcA at 0.313%-0.1%-0.2% for S. aureus, E. coli and C. albicans and 0.078%-0.2% for Salmonella ser. Typhimurium; OrO-Asc at 0.078%-0.25% for Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, 0.156%-0.25% for C. albicans, 0.313%-0.5% for S. aureus, and 0.625%-1% for E. coli.

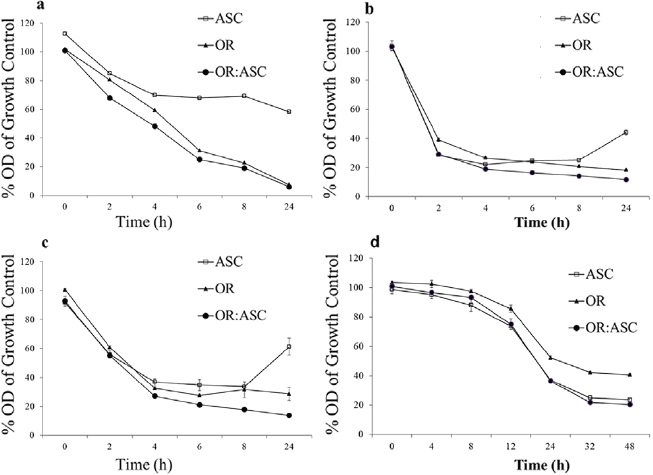

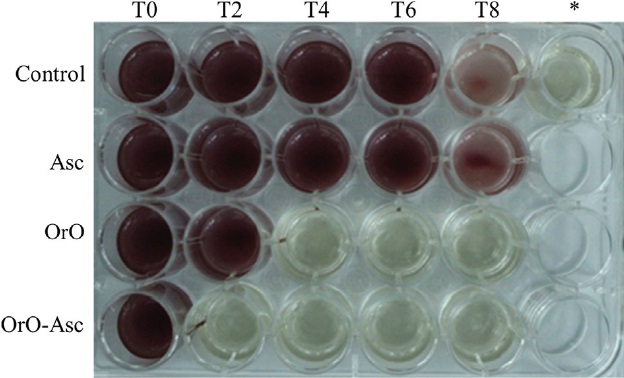

In agreement with the notion that any food preservative or additive should not alter or modify the food taste, oregano oil combined with ascorbic acid was selected as a mixture to evaluate the effect on microbial viability by time-kill curves. Previously, an assay was implemented with MIC values at 1X of Asc; 4X of OrO and 4X-1X of the combination OrO-Asc. Results demonstrated a strong inhibitory effect of Asc and OrO over microbial growth 2 h after the beginning of the assay, suggesting that a lower concentration should be assessed in order to implement the kill curves (data not shown). Figure 2 presents viability effects towards the four microorganisms. In the case of E. coli and Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, the checkerboard test results regarding the indifferent and additive synergistic activity of the OrO-Asc combination were confirmed (Figure 2a, 2b, respectively). In contrast to the checkerboard results, S aureus and C. albicans kill curves exhibited different effects on growth in relation to the OrO-Asc combination. In S aureus, it was possible to observe certain additive activity linked to growth; on the other hand, in C. albicans, an indifferent effect on growth was detected (Figure 2c, 2d). In addition to this, kill curves demonstrated that Asc exerted bacteriostatic or fungistatic activity, because E. coli, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and S. aureus growth was restored 4 h and 8 h after Asc addition. For instance, in Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, it was possible to observe growth reduction after 2 h of exposure to Asc, OrO and Oro-Asc. However, cells that were grown in culture media containing Asc were able to maintain viability throughout the experiment. This does not apply in the case of cells cultured with OrO or OrO-Asc which died in less than a couple of hours (Figure 3).

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Figure 2 Effect of oregano oil ascorbic acid (□, ASC), oregano oil ▲, OR) and the combination (●, OR:ASC) against Escherichia coli ( a), Salmonella ser. Typhimurium (b), Staphylococcus aureus (c) and Candida albicans (d). Each point represents the mean of triplicate determinations.

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Figure 3 The effect of treatments on Salmonella ser. Typhimurium cells viability during the first 8 hours of the time-kill curve. Line 1, M-H culture media; line 2, M-H media supplemented with ASC; line 3, M-H media plus OR; line 4, M-H media added with the combination OR:ASC. * M-H media non-inoculated.

Foremost, EO biological activity is attributed to two major chemical groups of low molecular weight, which include aromatic and aliphatic constituents (Bassolé & Juliani, 2012). A large amount of their antimicrobial properties seems to derive from oxygenated terpenoids; particularly phenolic terpenes, phenylpropanoids, and alcohols. The lipophilic characteristic of oils allows a simple diffusion through the microbial cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane.

Moreover, the cytotoxic activity appears to be linked to the structure disruption of polysaccharide, fatty acid and phospholipid layers, due to a multi-target hitting mechanism (Betoni, Mantovani, Barbosa, Di Stasi & Fernandes, 2006). An increasing number of studies have reported the microbial inhibitory effect of ascorbic acid alone or in combination with other compounds (Kallio, Jaakkola, Mäkil, Kilpeläinen & Virtanen, 2012). Other studies have demonstrated that synergism between ascorbic acid and phenolic compounds is due to the ascorbic acid ability to prevent the phenolic compounds oxidation (Hatano et al., 2008).

A great number of recent studies support the use of essential oils as natural food preservers that could be directly used in food products or in food cleaning products. As a result, researchers have been testing the antimicrobial action of a huge variety of safer essential oils. This behavior is a forceful reason to show interest in synergistic compounds that could be used to increase the antimicrobial activity of essential oils (Zanbuchini, Fiorini, Verdenelli, Orpianesi & Ballini, 2008).

Conclusions

Natural plant oils represent potential additives that may be employed to prevent bacterial and fungal growth in foods and replace the use of synthetic chemical preservatives. On the basis of the results of the study, we can conclude that oregano, cumin, laurel, and rosemary essential oils present antimicrobial activity against E. coli, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, S. aureus, and C. albicans. The combination of oregano oil and ascorbic acid could be adequate for use as food preservatives and provide essential protection against food-borne contamination without altering the taste, appearance and other characteristics of processed or prepared foods. Furthermore, the addition of ascorbic acid may be an alternative to increase the antimicrobial activity through the inhibition of phenolic compounds oxidation.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)