Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Investigaciones geográficas

On-line version ISSN 2448-7279Print version ISSN 0188-4611

Invest. Geog n.107 Ciudad de México Apr. 2022 Epub June 20, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14350/rig.60458

Articles

Subordinate financialization. The mortgage market for social housing in Mexico

* Departamento de Geografía Social, Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Circuito de la Investigación Científica s/n, Coyoacán, 04510, Ciudad de México, México. Email: lsalinas@igg.unam.mx

Emergent economies have entered the global financialization process in a context of dependency; the differences that characterize this process are discussed below under the concept of subordinate financialization. In this scenario, we analyze the securitization process based on mortgage-backed bonds issued by public housing funds in Mexico, which has boosted the social housing real-estate market. From the review of financial reports on stock certificates (CEDEVIS and TFOVIS), it is established that the sale of mortgage debt has allowed granting more mortgage loans to the beneficiaries, which is part of the state subsidiarity that supports the private real-estate sector, a situation that has characterized the massive-construction policy of the past two decades.

Keywords: housing policy; financial services; urban planning

La inserción de las economías subdesarrolladas al proceso global de financiarización se ha realizado en un contexto de dependencia, cuyas diferencias se discuten bajo el concepto de financiarización subordinada. En este escenario, se analiza el proceso de titulización a partir de la emisión de bonos respaldados por hipoteca emitidos por los fondos públicos de vivienda en México, lo cual ha dinamizado el mercado inmobiliario de vivienda social. A partir de la revisión de los informes financieros sobre los certificados bursátiles (CEDEVIS y TFOVIS), se establece que la venta de deuda hipotecaria ha servido para poder otorgar más créditos hipotecarios a los derechohabientes, lo que forma parte de la subsidiaridad estatal que respalda al sector inmobiliario privado, situación que caracterizó la política de construcción masiva de las últimas dos décadas.

Palabras clave: política habitacional; servicios financieros; urbanismo

Introduction

Today, there is a growing number of studies addressing the financialization of housing projects. However, it is pertinent to differentiate the works studying the financialization of housing in advanced economies and those that characterize this process in emerging economies. In this sense, the subordinate financialization concept proposed by Jeff Powell (2013) has given rise to a line of research in this regard (Kaltenbrunner and Painceira, 2018; Fernandez and Aalbers, 2020; Socoloff, 2020; Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner and Powell 2019), which has been adopted for the present work.

The interpretation of subordinate financialization responds to a context of the global capitalist economy. It can be linked to the center-periphery analyses (Wallertein, 1979) or to the Latin American studies performed since the sixties and seventies, particularly on the theory of dependence that challenges the benefits of international trade proposed by the classical economics school and explains underdevelopment through subordination to or dependency on developed countries.1

Since the Bretton Woods agreements, the structural reforms of the eighties and the implementation of neoliberal policies in Latin America allow the identification of elements that characterize subordinate financialization, highlighting that in dependence relationships, it is frequently dependent economies that finance investment projects in advanced economies. An example is the purchase of debt securities by advanced economies, mainly in dollars, due to pressures from international institutions, for dependent economies to increase their monetary reserves in foreign currency. Besides, the instruments that are developed for foreign investment maintain certain conditions favorable to the reduction of risks and thus guarantee returns to investors.

The objective of the present work was to analyze the characteristics of the securitization process of Mortgage-Backed Bonds (BRH; Bonos Respaldados por Hipotecas) issued by the most important public housing financing institution in Mexico, the Institute of the National Housing Fund for Workers (Instituto del Fondo Nacional de la Vivienda para los Trabajadores; INFONAVIT) and the Housing Fund of the Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (Fondo de la Vivienda; FOVISSSTE); these funds are discussed under the concept of subordinate financialization, highlighting that this has favored a dynamic production of social housing. In this way, the government has subsidized the real estate sector.

The text analyzes the theoretical perspectives that explain the financialization process, with particular focus on the characteristics of subordinate financialization as a central concept to analyze housing financing in the mortgage market in Mexico, highlighting the issuance of fiduciary certificates of public housing funds. This discussion supports the argument that subordinate financialization, in a context of State subsidiarity, has boosted the social housing market in urban outskirts, in which the housing policy was a social failure.

As already mentioned, a large number of publications address financialization in advanced economies, including information on recent features, financial instruments, characteristics, and impacts on everyday life. However, publications addressing financialization in dependent economies are still scarce (Kaltenbrunner and Painceira, 2018; Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner and Powell, 2019). This work contributes to this emerging literature.

Methodology

The analysis in the present study started by reviewing the available literature on financialization and, particularly, on subordinate financialization. In an interesting work, Socoloff (2020) addressed mortgage loans in Argentina, which are indexed to inflation, with payments being adjusted monthly even though wages do not increase accordingly. This article discusses how the securitization of mortgages by public housing funds has allowed granting loans according to the demand. To this end, we reviewed the annual reports of emissions of Housing Certificates known as CEDEVIS (including the Traditional Cedevis, Total Cedevis, and Total AG Cedevis modalities) issued by the Institute of the National Housing Fund for Workers (Fondo de la Vivienda del Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado; INFONAVIT), as well as the certificates called TFOVIS (integrated by various stock-market issues, such as FOVIHIT, TFOVIE, TFOVIS, TFOVICB, and FOVISCB) issued by the Housing Fund of the Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (FOVISSSTE) in various years, available on the websites of each institution. Additional information was obtained through a request based on the General Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information, particularly concerning TFOVIS.

According to Fernandez and Aalbers (2020), one of the central elements of subordinate financialization has been to strengthen monetary reserves in dollars by purchasing U.S. treasury bonds, so it was necessary to obtain information regarding Mexico's reserves through World Bank reports available in its website. Based on this information, we analyzed the subordinate financialization category for Mexico in general, and the issuance of Mortgage-Backed Bonds of public housing funds in particular.

Financialization Process

The late twentieth century has witnessed an intense debate, both conceptual and of various case studies, on economy’s financialization processes. It is evident that the available literature refers mostly to developed countries, for which studies rose exponentially in recent years (Aalbers, 2019). In fact, some authors relate the boom in publications on financialization to the 2007-2009 real-estate crisis (Lapavitsas and Powell, 2013; Fernandez and Aalbers, 2020). In parallel, there has been growing interest in research in dependent countries, albeit at a slower pace. In both contexts, this growing interest reflects the expansion of finance in the neoliberal model, as there is the perception that both the economy in general and everyday life in particular have become more financialized (Aalbers, 2019).

Several theoretical approaches have been proposed for the analysis of financialization. Besides, different definitions can be mentioned because given the lack of a universally accepted definition of financialization within the social sciences (Lapavitsas, 2016), even usually described as imprecise and chaotic (Aalbers, 2019). One of the most cited definitions is provided by Epstein (2005, p. 3), who states that "financialization refers to the increasingly important role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors, and financial institutions in the functioning of national and international economies." For his part, the Belgian geographer Manuel Aalbers (2019), applying a definition similar to Epstein's, relates financialization to various dimensions by defining it as the growing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements, and narratives, at various scales, which result in a structural transformation of economies, businesses (including financial institutions), states, and households.

The lack of a commonly accepted definition of financialization makes it a concept used only by "specialists", contrasting with concepts such as neoliberalism, usually used both in political and academic contexts as well as in popular discourse. The financialization concept is also contrary to concepts such as globalization (defined as the growth of the world market and the expansion of international financial markets, among other elements), which, although not precisely defined, it is usually used in popular discourse in addition to being widely used in political theory, international relations, and cultural theory (Lapavitsas, 2016; French et al., 2011; Aalbers, 2019). Nonetheless, this lack of conceptual accuracy allows dealing with the complex realities of contemporary societies, which for Aalbers (2019) explain an large part of the popularity of such "imprecise" concepts.

A review of the literature on financialization conducted by Aalbers (2019) states that it is commonly classified into three different conceptualizations: as a regime of accumulation; as the increase in value for shareholders; and as the financialization of everyday life. Additionally, three key theoretical perspectives can be identified (Lapavitsas, 2016): the first is the dominant paradigm of neoclassical economics (the dominant economic approach), the second is Marxist, and the third is the theory of the French regulation school.

Neoclassical economics highlight the importance of finance, but the central element is the presumption that financial dynamics is framed in a neutral process, so that supply and demand are the drivers of the stock market. Contrary to this, in an analysis of housing, Madden and Marcuse (2018) establish the need to politicize the economic dimension of housing, as discussing power relations is highly relevant. This is essential for the understanding of the process, considering that the financialization concept has Marxist origins (Lapavitsas, 2011 and 2016; Lapavitsas and Powell, 2013). In this regard, following the works of Hilferding, Epstein (2005) mentions that the financialization concept is often used to refer to the growing political and economic power of a particular economic group: the lessor class.

The third perspective is the French regulation school, which comprises two interrelated processes that have been extensively discussed in the capitalist system, namely Fordism and post-Fordism. In Fordism, the reproduction of capital is based on the absorption of surplus capital for the production of commodities; in post-Fordism, the circulation of capital and the development of financial markets allow investments to be directed towards the profitability of fictitious money. In post-Fordism, productivity is supported by high demand, but consumers maintain it through indebtedness rather than wages (as opposed to Fordism, developed by encouraging full employment). In addition, financialization affects employment and income inequality.

Lapavitsas (2009, 2011) highlights the role of banks in the financialization of workers' income, including an increase in loans (mortgages, general consumption, education, health, etc.) but also the expansion of financial assets (housing, retirement benefits, insurance, monetary market funds, etc.). The financialization of income is related to real wages that remain stagnant and the discontinuation of public financing in various areas (housing, retirement benefits, education, health, transport, etc.), that is, profits are obtained from wages and salaries (in addition to surplus value). This collection of profits has been called financial expropriation.

Financialization will be understood as a process that refers to various mechanisms that have allowed the reproduction of capital from financial activity involving the use of financial instruments, capital markets (stock exchange), economic opening and privatization of capital management (savings funds), free movement of capital (foreign investment), expansion of the credit system (banking institutions), and creation of futures market. This process is part of an accumulation pattern in which profits are increasingly produced through financial channels rather than trade and commodity production (Aalbers, 2019). The proposal outlined herein resembles concepts such as globalization -- and, particularly, neoliberalism --, which is why French, Leyshon, and Wainwright (2011) highlight the subject of the over-determination or origin between neoliberalism and financialization. It suffices to say that the development of financial instruments that revolutionized the capital market bloomed due to privatization, economic openness, and freedom in the circulation of capital. However, in a broad context, how can the emergence of financialization be understood?

In the analysis of the over-accumulation process of the capitalist system, Harvey focuses on how to solve the surplus capital issue, mentioning that capitalist production can absorb surpluses through long-term investments (infrastructure-real estate development), social expenditures (such as education and research), and the exploitation of the credit system and the formation of fictitious capital supported by the State, among others (Harvey, 1990, 2004). This will be necessary to the extent that:

the reallocation of surplus capital and labor to these investments requires the mediation of financial or state institutions capable of generating credit. An amount of "fictitious capital" is created that can transcend current consumption to be allocated to future projects, such as construction or education, that reinvigorate the economy (Harvey, 2008, p.16).

However, these are only temporary solutions because under capitalism -- Harvey says -- the surplus capital issue has no solution.

From the work of the Marxist economist Paul Sweezy, Lapavitsas states that financialization is associated with the fundamental problem of "surplus absorption." Currently, in what Sweezy calls mature capitalism, monopolies generate a surplus that cannot be absorbed by production, so that the reproduction of capital becomes stagnant:

stagnation is alleviated through an inexorable increase in unproductive consumption (...). Briefly, as production stagnated under the weight of the surplus, capital was derived to circulation, especially in speculative activities of finances. Financialization emerged when production was flooded by the investable surplus (Lapavitsas, 2011, p. 612).

From the above, one of the current characteristics is that the investment of the surplus is based not on the productive system but on the sphere of circulation -- the realm of finance. Capital reproduction is favored by investment in finance rather than production (Epsein, 2005). Therefore, Aalbers (2019) mentions that many scholars of financialization situate the beginning of financialization in the 1970s with the rise of neoliberalism, the industrial crisis in the West, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system.

The discussions on the unequal development of financialization around the world, from the so-called European Welfare State, Fordism, post-Fordism, globalization, and neoliberalism, refer to unique characteristics both between developed and dependent economies as well as between the various dependent economies, stemming from the historical development, institutional political contexts, and dependence on the particular trajectory, as mentioned by Theodore, Peck, and Brenner (2009) with the true notion of neoliberalism. Therefore, a topic for debate would be: what are the characteristics of really existing financialization of dependent economies? We recover Jeff Powell's proposal,2 stating that dependent economies have developed a process of subordinate financialization.

Subordinate Financing

There is a tendency to set conceptual generalizations for the understanding and communication of the characteristics of the processes affecting society. A valid question for understanding at various scales, however, lies in understanding generalizations as basic aspects that describe a process, as opposed to the description of realities. In a paper on the varieties of financialization in countries with advanced economies (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Japan), Lapavitsas and Powell (2013) focus on differentiating the characteristics of financialization between these countries. Likewise, the subordinate financialization concept stems from a generalization to differentiate it from the characteristics of advanced economies, but on the understanding that there are also differences between the various dependent economies. Rather than referring to Latin American financialization, we will refer to really existing financialization.

Returning to the differences between the Fordist mode of production and its transition to post-Fordism, we can also understand the differences with advanced economies. The incipient Fordist model and the subsequent flexibilization of Latin American economies, the financialization process took place in a scenario that evolved from industrialization to replace imported goods, which strengthened the domestic market, to a free-market economy. A central aspect was the modification of the monetary policy by liberalizing the interest rate and modifying the pattern from a gold-based currency to the dollar. Fernandez and Aalbers (2020) state that the central element of subordinate financialization is the type of integration of peripheries into global hierarchical monetary structures, which shapes the subordinate financialization process. Some works in Latin America highlight this monetary hierarchy. Socoloff (2019) contends that financing, as part of the financialization of housing, historically encounters structural limits in peripheral economies that are related to a subordinate currency in the international financial system. However, other elements that characterize financialization in Latin American economies can also be highlighted. Tamaso and Penha (2019) point out two peculiarities of subordinate financialization in Brazil, namely the high level of the interest rate and the restraint of the formation of secondary markets.

For his part, Harvey (2007) points out that international and national structures have been constituted that allows reducing the risks of investors in dependent economies and avoiding social revolts. In this way, the structural adjustment program administered by the Wall Street-Treasury Department-International Monetary Fund (IMF) complex manages the former while the focus of the state apparatus is to ensure that the latter do not occur. For example, the IMF covers, as best it can, exposure to risk and uncertainty of international financial markets, such as the crisis in Mexico in 1982, for which it had to face the serious losses suffered by the main investment banks in New York City that supported The Mexican debt at that time (Harvey, 2007).

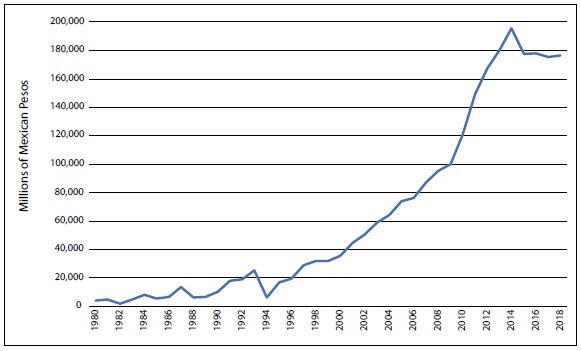

Additionally, and as mentioned above, the center-periphery relationship of financialization is related to the international institutional complexity. As part of monetary policy and for the granting of international loans from the IMF, the World Bank (WB) or the International Development Bank (IDB), these institutions "recommended" that dependent-economy countries should increase monetary reserves in dollars. Following such recommendations, the Mexican government has gradually increased its reserves by purchasing U.S. Treasury bonds (Chart 1), meaning that Mexico (and several Latin American dependent economies) have been financing the U.S. deficit. In this way, the vast accumulation of reserves (especially in dollars) is a direct consequence of the growing financial integration of emerging capitalist economies and their subordinate nature (Kaltenbrunner and Painceira, 2018), which, as already highlighted, is the main driver of the subordinate financialization process (Fernandez and Aalbers, 2020).

Source: Own elaboration with information of the World Bank (2020).

Chart 1 Total reserves of Mexico (gold plus dollars at current prices)

Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, and Powell (2019) explain subordinate financialization from production, circulation, and finance. As regards the first, these authors mention that when companies based in "emerging" economies participate in international production, their capture of the value created is lower versus companies higher in the international hierarchy, and must pay more to cover macroeconomic risk. As for circulation, strategies are developed from advanced economies in which the increase in household indebtedness maintains aggregate demand; such was the case of the subprime mortgage crisis, in which the mortgage market grew by at the expense of the families who purchased one or more households through credits and that could not cope with the debt. The lower levels of income and wealth in dependent economies may circumscribe such a model, encouraging the shift toward export-led growth (basically through contract manufacturing), a pattern consistent with their subordinate position within global production networks. This, in turn, fosters the development of domestic financial markets and may impose pressure to maintain low wages, profits, and taxes that support social reproduction systems (e.g., health, education, working conditions, savings funds, etc.), encouraging a shift towards the provision of private sources of welfare. This is the way in which emerging economies seek to become inserted into global circulation, through low labor costs and incentives to companies such as tax exemption.

Finally, the subordinate position of dependent economies concerning money and capital markets means that capital inflows are predominantly short-term, seeking financial returns rather than taking on productive risks. Investors participating in the markets of dependent economies seek to evade risks. As a result, the mortgage debt market of Mexico generated by public funds, according to rating agencies such as Moody's Mexico, Fitch Mexico, and Standard and Poors, is highly ranked (AAA). This indicates that these stock-market instruments have a stronger credit quality and a lower probability of loss of investments relative to other national credit issues, seeking risk reduction, in the understanding that they are debts granted from 30% of the employees’ income only, as discussed below. This same situation -- the authors contend -- serves to further consolidate the subordinate position of dependent economies in the global structure.

The instruments developed for the financing of housing projects have reached diverse markets, that is, mortgages for low-income populations. Rolnik (2017), taking up a quote from Alphonse Allais, states: "You have to look for money where it is: with the poor. There is not much they have, but there are many poor people"; therefore, mechanisms for the financing of microfinance should be generated. The Minha Casa Minha Vida housing program in Brazil and the public housing funds in Mexico (INFONAVIT and FOVISSSTE) have been established as ways to offer housing financing to previously excluded populations, as it mainly subsidized construction companies before (Neto and Salinas, 2019). In the case of Mexico, this subsidy decreased in the past six years, even leading to the bankruptcy of companies, including Casas Geo, the largest construction company in the country.

For the above, according to Queiroz and his coworkers (2020), subordinate financialization, as a global phenomenon, corresponds to new hierarchy setting, subordination, and domination within a scenario of power dialectic governing global capitalism.

Financialization of Housing in Mexico

As part of an incipient development of the welfare state, the Mexican government launched the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) in 1943 and the Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers (ISSSTE) in 1959. These institutions would be in charge of managing social benefits (retirement savings and benefits, health, and housing, among others), for workers in the private and the state sectors, respectively. As regards housing, two public institutions were created in 1972, becoming the most important tripartite solidarity savings funds for workers in the private and public sectors: INFONAVIT and FOVISSSTE, respectively. Through these institutions, the Mexican government seeks to cover workers’ access to housing.

The neoliberal policies that have been implemented in Mexico since the 1980s involved various amendments that would open the way for the financialization of the Mexican economy. As already mentioned, the resistance processes, the previous institutionality, and cultural aspects have jointly influenced the conversion into really existing financialization. This approach is used here for analyzing the characteristics of the financialization of housing in Mexico, differentiating the financialization between the real-estate market and the mortgage market -- the preferred options of international capitals (Abellán, 2019). The present work focuses on the latter process, highlighting the securitization of the BRH of public housing funds.

In this sense, we need to highlight the importance of different amendments within the neoliberal framework that have fomented subordinate financialization. In addition to the international context mentioned about insertion and dependence through the Bretton Woods agreements and international institutions, key aspects at the national level include the withdrawal of the State from housing construction (Puebla, 1999; Boils, 2004; Salinas, 2016), amendments in housing policy and public housing funds, the amendments to the Income Tax Law (articles 187 and 188) in 2004, and the privatization of the management of savings funds into the Retirement Savings System (SAR, in Spanish) in 1997. The companies in charge of the SAR participate in the Mexican Stock Exchange with resources from workers and invest in various financial instruments of the mortgage market.

In the mortgage market, a regulatory framework is implemented for loans, credits, and sale of mortgage debt, whose guarantee of payment is based on the mortgage of the real estate. One of its characteristics is that it not only "facilitated" the purchase of a household, but also influenced the increase in prices; importantly, the expansion of this market has translated into the increasing private ownership of housing (Aalbers, 2008). Therefore, public housing funds were used to foster this market since the 1970s.

In the dynamics of the mortgage market, the procedure known as securitization stands out, consisting in that non-bank institutions buy the portfolios of banks and mortgage institutions -- that is, loans -- and resell them as securities guaranteed by mortgages in the capital market - stock exchange (Rolnik, 2017). This process allows the institution that grants the credit to capitalize itself to grant additional loans.

In Mexico, since the creation of INFONAVIT and FOVISSSTE, a credit system for the acquisition of housing has been implemented, aimed at sectors of the population with formal employment (salaried workers). This system has had various amendments (Salinas, 2016), but the new sections or the amendments relating to financialization refer to how public funds can sell the debt of those accredited in the stock exchange to various investors to acquire greater liquidity and be able to grant further credits. This process is reviewed below.

Fiduciary Certificates of Public Housing Funds

Over the past two decades, housing policy has been characterized by massive construction works on the periphery of large and medium-sized cities. According to INEGI, by 2015 there were 31,949,709 households and 119,530,753 inhabitants. The housing policy materialized by stimulating demand through the granting of mortgage loans by public funds. FOVISSSTE granted 1,155,379 and INFONAVIT granted 7,222,319 mortgage loans during the period 2000-2018, figures that account for 73.67% and 79.60%, respectively, of all loans granted since its origins. The policy of massive construction of housing in Mexico was implemented as subsidies for construction companies; consequently, beyond supposedly benefiting those accredited, as claimed in public discourses, they have been affected because loans involve high interest rates (like bank credits). Furthermore, the interest schemes of credits are calculated in multiples of the minimum wage and in Units of Updated Measure (UMA), whose amount is linked to the minimum wage, which is adjusted annually, so the debt increases each year according to the rise in the minimum wage. In this way, monthly payments are allocated for paying the interest rather than the capital; hence, the public credit system involves payments that may last up to 30 years. This strategy, beyond being a mechanism to facilitate the conditions of access to housing, is part of a capital extraction and exploitation strategy - what Lavaptistas named financial expropriation (Lapavitsas, 2009, 2011).

The financialization of the mortgage market is evident in the securitization of the BRH of public funds. The mass-construction policy was launched at the beginning of the 21th century, along with the emergence of public bonds. The granting of mortgage loans by public funds since its origins (in the 1970s) has followed the traditional scheme of the primary market,3 but it was until the beginning of this century when the secondary market was constituted4, that is, when the BRH were generated. In 2004, INFONAVIT released to the stock market the Housing Certificates, known as CEDEVIS (which include Traditional Cedevis, Total Cedevis, and Total AG Cedevis), while FOVISSSTE issued certificates called TFOVIS (integrated by various stock-market issues, such as FOVIHIT, TFOVIE, TFOVIS, TFOVICB, and FOVISCB).

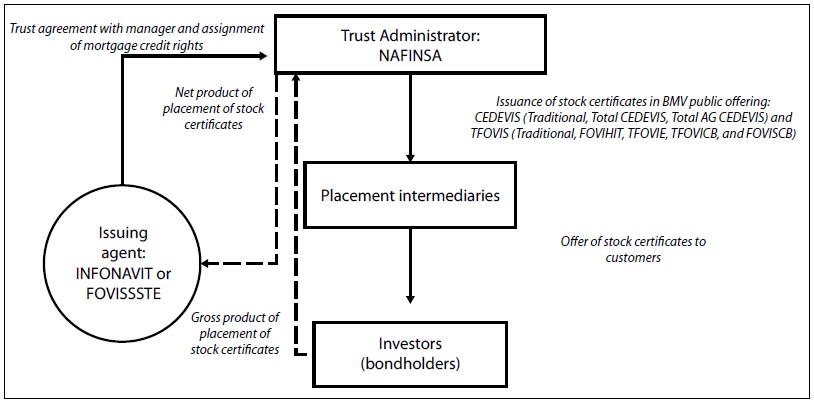

The securitization process takes place as follows (Figure 1): an issuing agent (INFONAVIT or FOVISSSTE) concedes the ownership or entitlement of some of its assets to an intermediary, for it to issue stock certificates on the stock exchanges; this intermediary is made up of the National Financial Development Bank (NAFINSA), backed by the assets of the issuing agent. The uniqueness of this financial mechanism or instrument is that, for the generation of bonds or certificates, the assets with the best rating of the issuing agent are separated from the rest, to build a portfolio with lower investment risks (Banorte, 2014). Thus, by transferring ownership or entitlement of the assets to the trust administrator (NAFINSA), the issuing agent obtains in exchange the net proceeds of the placement or sale of the bonds, while the latter, with the flow of future resources produced by the assets of the issuing agent, gives back the profits from the acquisition of bonds to investors or holders.

Source: Own elaboration from a report by INFONAVIT (2013).

Figure 1 Issuance of bonds (or stock certificates) backed by mortgages.

On the other hand, according to the reports of INFONAVIT (2013), the BRH rating agencies have been Moody's de Mexico, Fitch Mexico, and Standard & Poors, all of which have issued "AAA" ratings, indicating that these stock market instruments have a stronger credit quality, as well as a lower probability of investment loss relative to other credit issues. This is a major element for the demands of international investors, since the participation of investors in dependent economies is determined according to conditions that minimize risks; an objective of subordinate financialization is to produce mechanisms that guarantee profits to international investors. Which investors would invest in BRH issued in high-risk dependent economies?

The low risk that supports the "AAA" score granted to BRHs derives from the fact that these are credits aimed for salaried workers, whose monthly partialities of the credits cannot exceed 30% of the employee's income; to be granted a credit, employees are screened based on information about the work trajectory, age, and income, to determine whether they qualify as subjects of credit. In theory, these are risk-free loans, although it is known that macroeconomic instability and its impact on unemployment are elements that keep BRHs at risk; however, it would be difficult to put high-risk or subprime loans on sale to foreign investors, as happened in the United States of America, leading to the real-estate crisis.

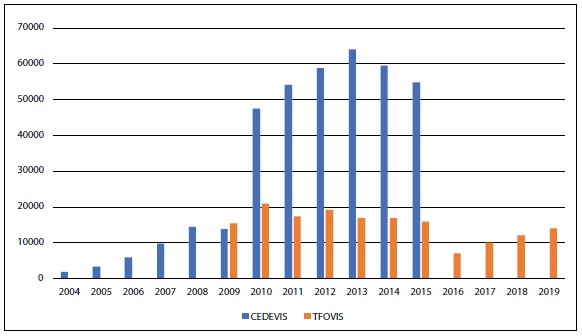

Chart 2 illustrates the behavior of BRHs issued by public housing funds, whose participation significantly increases those issued by INFONAVIT, while those of FOVISSSTE display certain regularity. To note, the objective of issuing BRHs is to use the resources received to grant additional credits with mortgage guarantee to a larger number of workers entitled to public funds. This securitization, with guarantees to investors, is part of subordinate financialization and state subsidiarity to support the real-estate dynamics of the private sector, with consequences that have been considered a social failure (Paquette and Yescas, 2009; Janoschka and Salinas, 2017).

Source: Own elaboration with information from the INFONAVIT reports.

Note: TFOVIS information was requested through the Access to Information Act; information from CEDEVIS was retrieved from its financial reports available until 2015.

Chart 2 Amounts of CEDEVIS and TFOVIS BRHs, in millions of Mexican pesos (2004-2019).

The process of financialization of housing, particularly securitization, exemplifies the instruments used by the State to create a scheme for the transfer of public resources to the private sector, with which it is the State that ultimately maintains the dynamics of the real-estate market afloat. This has led to the expansion of urban peripheries in medium-sized and large cities, which have given rise to diverse issues relating to mobility, transportation, and, above all, habitability (Salinas and Pardo, 2020). An example of this is housing abandonment, which represents a huge challenge.

Conclusions

Emerging (underdeveloped) economies have unique features within the global financialization process, whose dependence has been nurtured over the years. For Fernandez and Aalbers (2020), the insertion of low-income countries in unequal global financial and monetary relations creates a position of subordination. Subordinate financialization has enabled dependent economies to finance investments in developed economies, as evidenced by the purchase of debt issued by the Department of the Treasury of the United States of America (Harvey, 2007; Kaltenbrunner and Painceira, 2018; Fernandez and Aalbers, 2020), in addition, regulations on stock markets are being issued to guarantee returns to investors.

In Mexico, the subordinate financialization of housing has supported real estate companies through government subsidies but has affected the conditions of workers resulting from financial expropriation. Government subsidizing to private companies consists of the constitution of the mortgage credit system for the acquisition of households through public housing funds, which through securitization allow the issuance of mortgage debt stock certificates to finance further credits for workers in the public and private sectors. At the same time, this approach guarantees returns to investors from a payment protection fund, which covers 100% of mortgage loans, and through the screening of credit subjects (following the World Bank’s recommendations to reduce the overdue portfolio of public funds). At the same time, financial expropriation is evidenced in high interest rates and annual adjustments to the amounts of mortgage loans granted; additionally, the privatization of retirement savings has allowed the managers of these funds to invest in the mortgage market.

The subordinate financialization of housing and the subsidiary state contributed to the boost of the social housing market over the past two decades but represented a failure in terms of living conditions and urban development. Today, under the securitization of the social housing market, the housing policy is turning to subsidize the real estate market for the middle-class and high-income population from the generation of financial instruments, such as the Real Estate Investment Trust (FIBRAS, in Spanish). The questions raised by Madden and Marcuse (2018) are now highly relevant: how true is it that a housing policy seeks to solve the housing issues?

REFERENCES

Aalbers, M. (2008). The Financialization of Home and the Mortgage Market Crisis. Competition & Change, 12(2), 148-166. DOI: http://doi. org/10.1179/102452908X289802 [ Links ]

Aalbers, M. (2019). Financialization. En D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A.L. Kobayashi y R. Marston (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment, and Technology, Oxford: Wiley. [ Links ]

Abellán, J. (2018). Capitalismo, vivienda y financiarización: una aproximación a la obra de Manuel B. Aalbers. En L. Salinas y A. Pardo (Coord.), Vivienda y migración. Una mirada desde la geografía crítica. México: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, UNAM, Editorial Monosílabo. [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2020). Total de reservas (incluye oro, dólares a precios actuales) de México. Recuperado de https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/FI.RES.TOTL.CD?locations=MX. [ Links ]

Banorte. (2014). Tutorial: Bursatilizaciones. Estrategia de deuda corporativa México, 5 de agosto de 2014. Recuperado de: Recuperado de: http://casadebolsabanorteixe.com/analisis/DeudaCorporativa/especiales/Bursatilizaciones.pdf [ Links ]

Beltrán, S. (2016). Teorías de la financiarización y crisis financiera del 2008. Cuadernos de economía, 1(2), 4 - 12. Recuperado de http://cuadernosdeeconomia.azc.uam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/CE2_1BeltranRobles.pdf [ Links ]

Boils, G. (2004). EL Banco Mundial y la política de vivienda en México. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 66(2), 345-367. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid =S0188-25032004000200004 [ Links ]

Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A. y Powell, J. (2019). Subordinate Financialization in Emerging Capitalist Economies. Greenwich Papers in Political Economy, No. GPERC69. Recuperado de https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331487906_Subordinate_Financialization_in_Emerging_Capitalist_Economies [ Links ]

Cardoso, F. y Faletto, E. (1969). Dependencia y desarrollo en América Latina. México: Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Dos Santos, T. (2002). La teoría de la dependencia. Balances y Perspectivas. Madrid: Plaza Janés. [ Links ]

Dutta, S. y Thomson, F. (2018). Financierización: guía básica, España: Transnational Institute, FUHEM Ecosocial y ATTAC. Recuperado de: https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/financierizacionguia-basica.pdf [ Links ]

Epstein, G. (2005). Financialization and the world economy. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Fernandez, R. y Aalbers, M. (2020). Housing Financialization in the Global South: In Search of a Comparative Framework. Housing Policy Debate, 30(4), 680-701. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1681491 [ Links ]

French, S., Leyshon, A. y Wainwright, T. (2011). Financializing space, spacing financialization, Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 798-819. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510396749 [ Links ]

Gunder, A. (1976). América Latina: subdesarrollo o revolución. México: Era. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (1990). La condición de la posmodernidad. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2004) El nuevo imperialismo, Madrid: Akal. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2007) Breve historia del neoliberalismo, Madrid: Akal . [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2008). La libertad de la ciudad. Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, 7, 15-29. [ Links ]

INFONAVIT. (2013) Suplemento. CEDEVIS. Certificado de vivienda INFONAVIT. Más créditos, más empleo. Recuperado de https://portalmx.infonavit.org.mx/Cedevis /emisiones_cedevis.html [ Links ]

INFONAVIT. CEDEVIS Informes financieros varios años. Recuperado de: https://portalmx.infonavit.org.mx/Cedevis/emisiones_cedevis.html. [ Links ]

Janoschka, M. y Salinas, L. (2017). Peripheral urbanisation in Mexico City A comparative analysis of the uneven social and material geographies in low-income housing estates. Habitat International, 70, 43-49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.10.003 [ Links ]

Kaltenbrunner, A. y Painceira, J. (2018). Financierización en Amrica Latina: Implicancias de la integración financiera subordinada. En M. Abeles, E. P. Caldentey y S. Valdecantos (Eds.), Estudios sobre financierizacion en America Latina (pp. 33-61). Santiago: CEPAL. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18356/a213e4a5-es [ Links ]

Lapavitsas, Costas. (2009). Financialised capitalism: crisis and financial expropriation. Historical Materialism, 17(2), 114-148. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1163/156920609X436153 [ Links ]

Lapavitsas, C. (2011) Theorizing financialization, Work, employment and society. 25 (4), 611-626. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011419708. [ Links ]

Lapavitsas C. (2016). Beneficios sin producción. Cómo nos explotan las finanzas. Madrid: Traficantes de sueños. [ Links ]

Lapavitsas, C. y Powell, J. (2013). Financialisation varied: a comparative analysis of advanced economies. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6, 359-379. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst019 [ Links ]

Madden, D. y Marcuse, P. (2018). En defensa de la vivienda. Madrid: Capitán Swing Libros. [ Links ]

Marini, R. (1977). Dialéctica de la dependencia. México: Era . [ Links ]

Neto, P. y Salinas, L. (2020). Financialisation of housing policies in Latin America: a comparative perspective of Brazil and Mexico. Housing Studies, 35(10), 16331660. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1680815 [ Links ]

Paquette, C. y Yescas, M. (2009). Producción masiva de vivienda en Ciudad de México: dos políticas en debate. Centro-h, 3, 15-26. Recuperado de: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers10-12/010047762.pdf [ Links ]

Powell, J. (2013). Subordinate financialisation: a study of Mexico and its non-financial corporations. Tesis de doctorado. Londres: Universidad de Londres. Recuperado de https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/19090664.pdf [ Links ]

Puebla, C. (1999). Del Estado interventor al Estado facilitador. Ciudades, 11(44), 23-29. [ Links ]

Queiroz, L., Pouchain, I., Diniz, N. y Fidalgo, T. (2020). Nexos Financeirização/Urbanização: construindo um marco teórico. En L. Queiroz (Ed.), As metrópoles e o capitalismo financeirizado. Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital, Observatório das Metrópoles. [ Links ]

Rolnik, R. (2017). La guerra de los lugares. La colonización de la tierra y la vivienda en la era de las finanzas. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Lom. [ Links ]

Salinas L. (2016). Política de vivienda y gestión metropolitana en la expansión de la periferia de la ZMCM. Cuadernos Geográficos, 55(2), 217-237. Recuperado de https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/cuadgeo/article/view/3888/5148 [ Links ]

Salinas, L. y Pardo, A. (2020). Vivienda social y habitabilidad en la periferia de la Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 76, 51-69. [ Links ]

Socoloff, I. (2019). Financiarización de la vivienda y crédito hipotecario en Argentina: el rol del Banco Hipotecario. En L. Shimbo y B. Rufino (Org.), Financeirização e estudos urbanos na América Latina (p-). Rio de Janeiro: Editora Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Socoloff, I. (2020). Subordinate Financialization and Housing Finance: The Case of Indexed Mortgage Loans’ Coalition in Argentina. Housing Policy Debate, 30(4), 585-605. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1676810 [ Links ]

Tamaso, B. y Penha, C. (2019). Crise econômica e o setor imobiliário no Brasil: um olhar a partir da dinâmica das maiores empresas de capital aberto (Cyrela, PDG, Gafisa e MRV). En L. Shimbo y B. Rufino (Org.), Financeirização e estudos urbanos na América Latina (p-).Rio de Janeiro: Editora Letra Capital . [ Links ]

Theodore, N., Peck, J. y Brenner, N. (2009). Urbanismo neoliberal: la ciudad y el imperio de los mercados. Temas Sociales, 66, 1-12. [ Links ]

Wallerstein, I. (1979). The Capitalist World-Economy. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

1For further analysis, refer to the works of Raúl Prebisch and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), as well as Cardoso and Faletto (1969); Dos Santos (2002); Gunder (1976); and Marini (1977), among others.

2According to Lapavitsas (2016), Jeff Powell first suggested (2013) the term "subordinate financialization."

3The scheme of the primary mortgage market starts from the granting of new mortgage loans by financial institutions (banks, public funds, etc.) and the beneficiary or creditor is the one who receives the credit.

Received: August 10, 2021; Accepted: February 24, 2022; Published: March 30, 2022

text in

text in