Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Investigaciones geográficas

versión On-line ISSN 2448-7279versión impresa ISSN 0188-4611

Invest. Geog no.54 Ciudad de México ago. 2004

Geografía humana

Trade liberalization and productivity growth: some lesson from the Mexican case

Liberalización comercial y crecimiento de la productividad: algunas lecciones del caso mexicano

Adrian de Leon Arias*

* Centro Universitario de Ciencias Económico Administrativas (CUCEA), Universidad de Guadalajara, Periférico Norte 799, Edificio de Rectoría, Planta Alta, Núcleo Universitario Los Belenes, 45100, Zapopan, Jalisco. E-mail: laaO2511@cucea.udg.mx

Recibido: 20 de enero de 2003

Aceptado en version final: 31 de mayo de 2004

Abstract

Applying the most recent methodology for explaining economic growth differences across countries (Barro, 1997), education and infrastructure have been considered relevant in explaining productivity growth differences in Mexican urban manufacturing (De Leon, 1999). In this article, I evaluated whether there is a significant change in the relevance of these variables under trade liberalization. In particular, I evaluated the hypothesis that trade liberalization would promote productivity growth in the northern cities as result of the dynamic effect of trade given that these cities are close to the new central market for Mexican manufacturing and the lost of relevance in the previous accumulated growth factors (Livas y Krugman, 1992 and Hanson, 1994). In contrast to that hypothesis, I observe that urban manufacturing close to the U.S.A. did not show a better performance than the rest of the cities as expected and that accumulated growth factors, such as education and infrastructure are still relevant in explaining productivity growth across urban manufacturing in Mexico.

Key words: Economic growth, regional and urban economics, Mexico, trade liberalization.

Resumen

Utilizando la más reciente metodología para explicar las diferencias en el crecimiento económico entre países (Barro, 1997), educación e infraestructura han sido consideradas como factores relevantes para explicar diferencias en el crecimiento de la productividad en las manufacturas urbanas mexicanas (De León, 1999). En este artículo se evalúa si ha habido un cambio en la relevancia de esta variable bajo liberalización comercial. En particular, se evaluó la hipótesis de que liberalización comercial promovería el crecimiento de la productividad en las manufacturas de las ciudades del norte mexicano como resultado de los efectos dinámicos del comercio, dado que estas ciudades están más cercanas al nuevo mercado central para las manufacturas mexicanas y quizás a la pérdida de relevancia en los factores de crecimiento previamente acumulados (Livas y Krugman, 1992; Hanson, 1994). En contraste a esta hipótesis, se observa que las manufacturas en ciudades cercanas a los Estados Unidos no mostraron un mejor desempeño productivo que el resto de las manufacturas en el resto de las ciudades y que factores de crecimiento previamente acumulados, como educación e infraestructura, son aún relevantes para explicar el crecimiento de la productividad entre las manufacturas urbanas mexicanas.

Palabras claves: Crecimiento económico, economía urbana y regional, México, liberalización comercial.

INTRODUCTION

How does trade liberalization affect productivity growth across regions? In this article, I study the effects of economic integration with the United States on productivity growth in Mexican urban manufacturing within the framework provided by the new growth empirics (see, for instance, Barro, 1997). That international trade causes an increase in productivity growth in sectors or firms involved in trade is a basic insight of trade theory. However, the effect of trade on the spatial economic performance is not clear. Economists have begun to pay closer attention to regional economic growth patterns in order to understand how the transition to an open economy affects local economic growth.

The basic theme of recent economic growth literature is that externalities are related to the productivity of firms in a location in two ways: i) to the facilities for acquiring knowledge or skills due to the extensión of the market, and ii) to the previous local accumulation of resources related to productivity growth. According to the type of growth factors involved in these externalities I cali the first type of effect, "trade-induced growth-factors", and the second ones "localized endogenous growth factors".

The "trade-induced-growth-factors" (TIGF) are the most familiar kind of factors that underlie the explanation of the positive effect of trade on productivity growth. According, Adam Smith, for instance:

By means of [foreign trade], the narrowness of the home market does not hinder the división of labor in any particular branch of art or manufacture from being carried to the highest perfection. By opening a more extensive market for whatever part of the produce of their labor may exceed the home consumption, it encourages them to improve its productive powers. (Smith, 1776, vol. 1:413, quoted from Skott and Ros, 1997).

For more recent explanations on economic growth and trade liberalization, See Romer (1986 and 1990), Grossman and Helpman (1991), and Young (1991). In most of these explanations, growth is related to market extensión.

"Localized endogenous growth factors" (LEGF) are related to factors that "complement" physical capital, such as human capital public as well as infrastructure that-genérate a technological externality that affects productivity growth positively.

Most empirical studies have evaluated the relationship between trade liberalization and productivity growth based on the first set of externalities, the "trade-induced-growth- factors" (TIGF), see Edwards (1995), but in any case, there has been no conclusive research that includes both growth factors. I argue in this article that the explanation of the trade effect on productivity growth is not conclusive because of the absence of the LEGF in the previous works. Some studies, such as Hanson (1994), have looked into this relationship but for different reasons, as shown later in this article, they have not been satisfactory.

Recent changes in Mexico's trade policy make the country an ideal case study. In 1985, after four decades of import substitution industrialization, México began to open its economy to trade. The government enacted reform swiftly, eliminating most trade barriers in the following three years. Mexico's location in North America makes trade liberalization equivalent to economic integration with the United States. For Mexican firms, proximity to foreign markets means proximity to the U.S. market. Yet, Mexico's closed-economy main industrial centers are located far from the United States. Since the 1950's, manufacturing capacity has been concentrated in the country's interior around the largest cities such as Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey. While foreign-market access lures firms to the Mexico-U.S. border, the existing pattern of growth productivity due to "localized growth factors" works against this shift.

In this article, I estimate the change in productivity growth across urban manufacturing before and after trade reform as a function of trade related and localized growth factors, as well as other control variables. I define "trade-induced-growth factors" as the effect of the location of a particular urban manufacturing on the northern Mexican border. I have included educational attainment and infrastructure within the "localized growth factors ". If trade related-growth-factors matter, I shall observe that productivity growth will be higher in cities close to the United States. If localized factors matter, I shall observe that productivity growth will be higher in those with higher education attainment and more public infrastructure.

Section 2 in this article reviews the empirical and theoretical context of growth theory, trade theory and economic geography. Section 3 then describes the empirical model that will be used to explain the impact of trade liberalization on productivity growth in urban manufacturing. In Section 4, the results of the empirical analysis are reported.

Section 5 shows a sensitivity analysis that complements the previous results, while Section 6 present the main findings of the article.

EMPIRICAL AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In de León (1999), I reviewed how the literature on economic growth has been developed in explaining differences in productivity growth among cities or regions. In this article, trade liberalization is introduced and some implications for the Mexican case will be explored. More specifically, I explore how differences in urban economic growth can be affected, taking into consideration transportation costs and variables related to recent growth models. In the Mexican case, I argue that since economic growth is based on specific urban characteristics that are created over time in cities, history matters when an economy is opened.

Specifically, what are the regional productivity implications when a previously closed economy is opened by trade tariff reductions? If trade liberalization implies, in regional terms, a relocation or moving of the central market for "national" firms, from the "interior" to the "foreign" market, how does this relocation changes the pre-trade differences in productivity growth?

This idea can be easily illustrated in the Mexican urban manufacturing case. Under import substitution industrialization (ISI), as the infernal market was to be promoted, the central market was where the people were. As has been the case with others countries under ISI, these locations were the largest central cities. Under trade liberalization, because the internal market is no longer protected, and because of export no longer protected, and because of export promotion strategies (EPS), the central market is now located closer to the "foreign" market, in Mexico's case, in its northern cities. What have been the implications of this change on the differences in the rate of productivity growth? According to Livas and Krugman (1992) and Hanson (1994), if the externalities due to market extensión are important, then we should see higher productivity growth rates in the region spatially close to the new central market, i.e. the northern cities, not around the largest cities as happened before trade liberalization. In particular, Hanson (1994) finds that, consistent with market extension considerations, employment growth, as related to productivity growth, is higher in regions that are relatively closer to the United States. He adds that the results describe the decomposition of the Mexico City manufacturing belt and the creation of a smaller, broadly specialized center in Mexico's north.

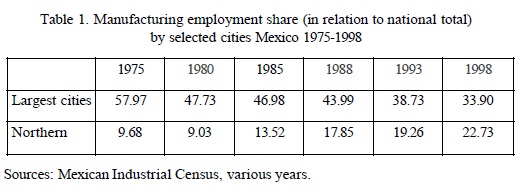

In order to evaluate the former argument, in de Leon (1999), I presented data at the state level that confirms Livas's and Krugman's (1992) and Hanson's (1994) findings based on employment and output growth but not productivity levels and growth rates. Table 1 (2) confirms these results at urban manufacturing level; the manufacturing employment share in relation to the national total, for the three largest cities in Mexico (Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey) decreased from 57.97 to 33.90 between 1975 and 1998. At the same time, Northern cities, those located in states close to the border (1) excluding Monterrey, also show an increasing share of total employment, from 9.68 to 22.73 percent. The same behavior can be observed for manufacturing output by selected cities (). We now turn to analysis of the performance of both kinds of cities in terms of productivity levels and rate of growth.

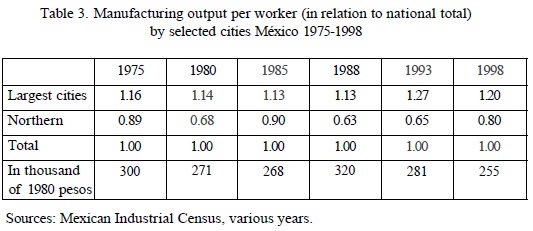

If we observe the behavior of labor productivity for the same cities during the same period, our perception about the performance of each set of cities changes. Table 3 presents the level of output per worker, labor productivity, for selected cities from 1975 to 1998. The largest cities in México have kept, with some variations, their productivity steady in relation to the national level. At the same time, Northern cities have seen their labor productivity level decrease in relation to the national average. The data is reported in comparative terms in order to "isolate" variations observed at the national level. In any case, our interest is in observing comparative performance across cities.

Table 4 presents labor productivity growth data for two periods, 1975-1985 and 1985-1998, following the suggestion of Hanson (1994) about considering 1985 as the year when trade liberalization took place. For the first period, Largest cities grew more slowly than the national growth rate as Northern cities as much as the national growth rate. But for the second period, 19851998, that is, under trade liberalization, labor productivity in the largest cities grew faster than in the northern cities and even faster than the national average. As a result, for 1975-1998 period labor productivity for the largest cities shows about a 7 percent in-crease in relation to the growth rate for national manufacturing, but northern cities show a lower rate of productivity growth than the national average.

At this point, it is clear that even though Krugman's, Livas's and Hanson's conclusion apply to productivity. How, then, can a better story be told?

Krugman's introduction of dynamic externalities has certainly extended the analysis of the impact of trade on regional growth. However, his analysis is limited. Since he observes externalities as related exclusively to market size and not to the specific conditions that promote productivity growth or regional competitiveness.

Later in this section, I will introduce the sources that promoted productivity as a whole for regional and urban areas according to new growth theories. Introducing these sources will be seen to have relevant implications for the impact of trade on regional growth differences.

As shown in de León (1999), new economic growth models have analyzed the kinds of urban characteristics that are the relevant sources of endogenous growth. In this research, I have considered: education, as the engine of growth, and infrastructure. Because economic growth is promoted by urban characteristics related to growth factors that are created over time in cities, history may matter when an economy is opened. In particular, if this is the case, trade liberalization should make proximity to the foreign market importan, as suggested by Krugman and others, but it does not necessarily weaken other externalities generated in some regions or cities. In other words, mere agglomeration of economic activity is not the only source of externalities. Specific characteristics related to variables related to new growth models in the location must also be considered. Moreover, if urban characteristics related to variables tied to recent growth models are relevant, the outcome, in terms of regional growth patterns under trade liberalization, cannot be determined solely by considering such variables as transportation costs. If this is the case, adjustment away from the closed-economy growth pattern is likely more protracted. Trade causes proximity to the new central market (the U.S. market, in the Mexican case), more important, but it does not directly weaken the externalities generated by factors related to endogenous growth. Moreover, the sectoral reallocation of economic activity that trade brings may cause some closed economy centers to grow in the short or medium term. As specialization redirects activities from some industries to others, the relevance of these urban characteristics makes specific industrial centers, all else being equal, the ones more likely to benefit.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

The recent work on growth empirics suggests a simple empirical approach for studying how regional productivity growth adjusts to trade liberalization. To the extent that market extension affects urban performance, we expect trade liberalization to cause a productivity growth in cities that are located close to the U.S. To the extent that "localized factors" matter, we expect that cities which have accumulated physical capital as well as human capital and infrastructure to grow in comparison to those which have not accumulated said factors.

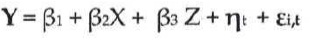

My estimation will be based on the next equation. This equation is extended to include a dummy variable for time. The "time dummy-variable" is 1 for the period 1985–1993, and 0 otherwise. Because Mexico initiated trade liberalization in 1985, it will proper to define two set of observations about differences in productivity growth by cities: from 1975 to 1985, the period preceding trade liberalization, and from 1985 to 1998, the period following the initiation of trade reform. See Hanson (1994) for a detailed explanation on when the Mexican economy was opened. The new model to be estimated will have the following general form:

where Y is the growth rate of added value per worker, X and Z are matrices of explanatory variables, β1is the common constant, η1 is the time-dummy-variable and εi,t are residuals.

Regarding the explanatory variables, matrix Χ contains those variables other than my specific growth factors that potentially explain differences in productivity or longterm growth, such as output per worker at the beginning of the period. Matrix Z includes the two types of factors related to endogenous growth models infrastructure and human capital. Matrix Z also includes a dummy variables for those urban manufacturing located in the northern states. See Appendix for definitions of variables and their means and standard deviations. There are 60 potential observations per time period that corresponds to 60 major manufacturing centers in Mexico. The manufacturing center in Mexico were defined according the definition of metropolitan areas proposed by Garza and Rivera (1994).

TRADE LIBERALIZATION AND GROWTH

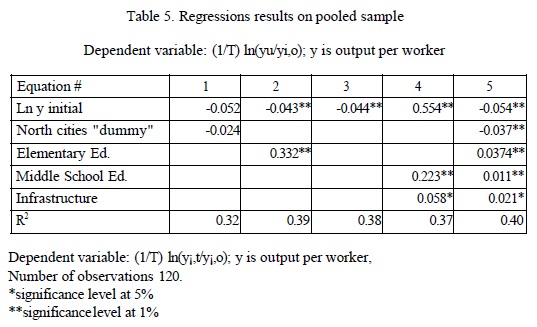

This section presents the results of the model developed in the prior section pooling the data for the two periods, 1975-85 and 19851998. The analysis will be developed using a generalized least squares estimation model in order to considering a panel model with random effects. The Table 5 shows the specific variables that are included for each regression; for example, in equation 1, I include the output per worker at initial period (Ln y), my control variable, and the North cities dummy as part of my explanatory variables; for equation 2, I include on the left side of regression equation the In y initial and elementary education, and so on. In relation to the expected sign in the other estimates, I observe in equation 5 that all "endogenous growth factors" show an expected positive sign. The North regional dummy shows a negative sign in equations 1 and 5, that supports my hypothesis about the poor performance of manufacturing in the Northern cities in terms of productivity growth. Note that this estimate is statistically significant.

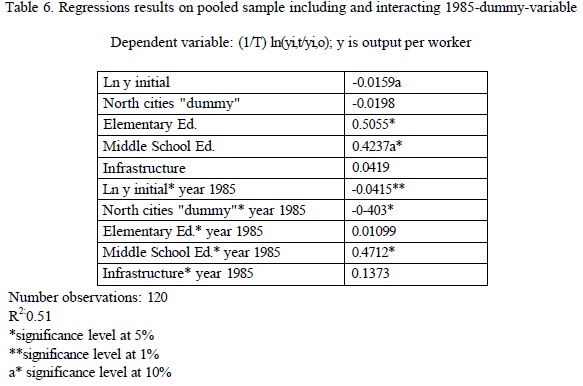

To formally test my hypothesis on the effects of trade liberalization, I use the former regression model, including an "interactive" dummy variable for the year 1985, for each one of the explanatory variables. If trade liberalization has indeed caused a structural break, the regression coefficients in the period after 1985 will differ from those before 1985. The results are presented in Table 6. Comparing periods 1975-1985 and 1985-1998, I observe an increasing convergence rate after 1985, and increasing negative effect on northern cities location. All the other explanatory variables show an expected positive sign after 1985.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

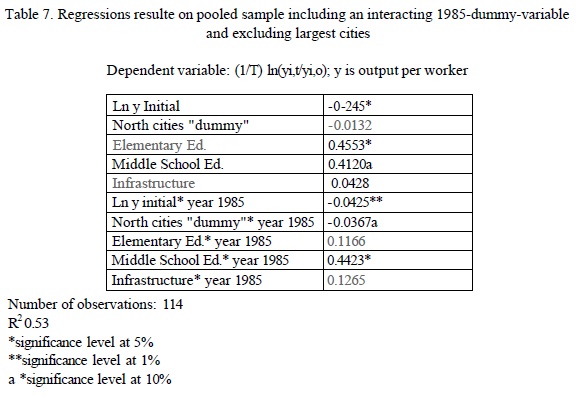

To check the robustness of these findings, I estimate the regression equation shown in Table 6, imposing some restrictions on the sample. One possibility is that the results are driven by the "dis-industrialization" of the largest cities, and that in outlying cities the role of specialization and location close to the U.S.A. as negative growth effects which are evident in Table 5 and 6 do not exist. To test this, the urban manufacturing variables of largest cities (Mexico city, Monterrey, and Guadalajara) are dropped from the sample, which reduces the number of observations from 120 to 114 in the pooled sample. Table 7 shows the results. Coefficient magnitudes and patterns of significance are virtually identical to those in the corresponding Table 6.

A second possibility is that the results are caused by regional variations in adjustment to Mexico's stabilization policies in the late 1980's. Mexico experienced a severe recession over the 1986-1987 period. Due to the presence of the maquiladora industry, cities along the Mexico-U.S. border were oriented toward export production before trade liberalization. Producers in interior cities may have suffered a large fall in demand for their goods in comparison with border producers during 1985-1993 due to the fact they were primarily oriented toward production for the domestic market. What may be poor performance of northern cities in terms of output per worker may only have been the uneven effect of different employment growth. Employment grows faster in northern cities than in the rest of the country. To verify if the presence of maquiladoras changed the results, the urban manufacturing located in the Northern border region is dropped from the sample. Table 8 shows that the results are very similar to those in Table 6.

So far, I have pooled all urban manufacturing together encompassing all manufacturing branches, which poses the assumption that endogenous growth factors matter equally for all manufacturing branches. This approach is somewhat restrictive. However since some manufacturing branches produce goods that are widely traded across regions or that are intensive in the use of relatively immobile inputs, I plan to take this restriction into consideration in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has empirically examined the growth effects of trade liberalization. It focuses on the role of human capital and infrastructure that encourage growth of preexisting manufacturing centers and the locations with good access to foreign markets, which encourages the growth of cities along the Mexican border. I have compared productivity growth in Mexican urban manufacturing before and after trade liberalization. Consistent with the argument that productivity growth in the new areas (Northern cities) is restricted by the unavailability of non-physical capital in those areas, I have found that manufacturing in the northern cities shows poor performance in productivity growth.

The empirical results describe the general features of the post-trade reform pattern of productivity growth in Mexican urban manufacturing. Under trade liberalization, there was not a northward shift in productivity growth. Mexico's closed-economy manufacturing centers around the largest cities have not diminished in importance in terms of productivity growth as firms relocate their activities to cities in northern Mexico where they have better access to foreign markets. The implementation of the North American they have better access to foreign markets. The implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which should reinforce the motivation for firms to locate near the United States, has not been promoting a higher rate of productivity growth.

Finally, it is relevant to note that one of the limitations of my research is the problem about price deflactor. I have used the GNP deflactor. However, while I am taking into consideration foreign trade relations, trade volume is affected by exchange rates and import taxes, as well as, transfer prices among multinational firms. In further research, analysis at the firm level could help to work out this restriction.

NOTES:

1 Furthermore, these states are included in a special tariff structure the allows in-bound production free of tariffs from and to the United States. This structure created the maquiladora operation.

REFERENCES

Barro, R. J. (1997), Determinants of Economic Growth, a Cross-Country Empirical Study, MIT Press Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Edwards, S. (1995), Crisis and Reform in Latin America: From Despair to Hope, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Garza, G. and S. Rivera (1994), Dinámica Macro económica de las Ciudades en México, INEGI, México. [ Links ]

Grossman, G. M. and E. Helpman (1991), Innovation and Groiuth in the Global Economy, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Hanson, G. (1994), "Regional adjustment to trade liberalization", NBER Working Paper No. 4713, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

León, A. de (1999), Trade Liberalization and Endogenous growth, Ph. D. Dissertation. University of Notre Dame, IN., Chapter 3. [ Links ]

Livas Elizondo, R. and P. R. Krugman (1992), "Trade Policy and Third World Metrópolis", NBER Working Paper No. 4238, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Romer, P. M. (1986), "Increasing returns and longrun growth", Journal of Political Economy, 94, pp. 1002-1037. [ Links ]

Romer, P. M. (1990), "Are nonconvexities important for understanding growth?", NBER Working Paper No 3271, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Skott, P. and J. Ros (1997), "The 'Big Push' in an open economy with nontradable inputs", Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, vol. 20, Fall, pp. 149-162. [ Links ]

Young, A. (1991), "Learning by doing and the dynamic effects of international trade", Quarterly Journal of Economics, May, pp. 369-405. [ Links ]

Young, A. A. (1927), "Increasing returns and economic progress", Economic Journal 38, 4, December, pp. 527-542. [ Links ]