Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.20 Guadalajara 2023 Epub 17-Abr-2023

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2023.8452

Articles

General theme

Feminist and Sexual Dissidence Mythologies: distorting meaning and depoliticizing through humour1

*Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. kb.barcenas@sociales.unam.mx

This article examines the way coercive memes-whether those against feminism or sexual dissidence-that circulate through social media opposing “gender ideology” in Mexico, constitute practices of symbolic domination that perpetuate forms of oppression. Following the semiological perspective of Roland Barthes, coercive memes are analyzed as mythologies, which makes it possible to focus on three of their ideological functions: distorting meaning, naturalizing, and depoliticizing. The methodological strategy is based on the analytical centrality of returning to the ethnographic archive.

Keywords: Gender ideology; feminism; mythologies; memes; humor

En este artículo se examina la manera cómo los memes disciplinarios -antifeministas y en contra de la disidencia sexual- que circulan en perfiles contra la “ideología de género” en México, constituyen prácticas de dominación simbólica que perpetúan modos de opresión. Siguiendo la perspectiva semiológica de Roland Barthes, los memes disciplinarios son analizados como mitologías, lo cual permite focalizar en tres de sus funciones ideológicas: deformar el sentido, naturalizar y despolitizar. La estrategia metodológica parte de la centralidad analítica de volver al archivo etnográfico.

Palabras clave: Ideología de género; antifeminismo; mitologías; memes; humor

Este artigo examina como os memes disciplinares -antifeministas e contra a dissidência sexual- que circulam em perfis contra a “ideologia de gênero” no México constituem práticas de dominação simbólica que perpetuam modos de opressão. Seguindo a perspectiva semiológica de Roland Barthes, os memes disciplinares são analisados como mitologias, o que nos permite focar em três de suas funções ideológicas: distorcer o significado, naturalizar e despolitizar. A estratégia metodológica assenta na centralidade analítica do regresso ao arquivo etnográfico.

Palavras-chave: Ideologia de gênero; antifeminismo; mitologias; memes; humor

Introduction

One of the most important cultural features shaped by the uses and appropriations of the Internet is the shattering of an imaginary based on freedom and equality -as happened with modernity as a project-associated with the construction of a better world, thanks to information and communication technologies. This is due to the onslaught of various types of domination constructed on the basis of these resources, designed to maintain forms of oppression that now use humour and laughter to target those who have historically been marginalized and stigmatized.

Nagle (2017) defines these practices as “online culture wars” (p. 12). Following her approach, one can argue that memes, particularly those called coercive memes here, are one of its most important weapons. The speed and scope with which these resources circulate and go viral thanks to the technological infrastructures of social digital media have enabled them to be appropriated and recontextualized around the world, which is why the domination they exert over historically oppressed populations constitutes a global phenomenon.

This can be seen, for example, in the central role played by images and irreverent humor in the white supremacist nationalist movement known as the Alternative Right, launched in the United States during the presidential campaign of Donald Trump (Nagle, 2017; Ruocco, 2020) and extreme right-wing groups in Finland (Hakoköngäs et al. 2020) but also in studies on racism such as the ones conducted by Yoon (2016) on the Memecenter platform (www.memecenter.com), and Harvey et al. (2019) on anti-vaccine memes on Facebook websites, as well as the research by Askanius (2021) on aesthetic and cultural expressions in neo-Nazi memes in Sweden.

The forms of domination and oppression through memes and humour based on the androcentrism and binarism of the sex-gender system have spawned hate speech against sexual dissidence as well as anti-feminism2 on the Internet, which has been analyzed in studies such as those conducted by Drakett et al. (2018), Ging and Siapera (2019), Villar-Aguilés and Pecourt Gracia (2021). To determine the scope of this problem in Mexico, we draw on the work undertaken by García and Bailey (2020) on the perception of the feminist protest #UnVioladorEnTuCamino (A rapist in your way). As part of the analysis of 624 memes, the authors found that 82% expressed a negative perception of this protest (García & Bailey).

However, the approach adopted here has its roots in the creation of an anti-gender movement or one against “gender ideology”,3 which emerged in the mid-1990s, yet which can currently be regarded as global in scope, with forms of articulation and action that are replicated in different parts of the world as has already been analyzed elsewhere (Bárcenas Barajas, 2020, 2021, 2022). For this reason, the work by Villar-Aguilés and Pecourt Gracia (2021) on the hashtag #StopFeminazis in Spain, which was circulated by the organization “Hazte oír” (Make Yourself Heard) within the framework of a campaign whose main resource was a bus tour of certain cities in this country with the motto “It is not gender violence, it is domestic violence, #StopFeminazis” is important.4

Considering the forms of domination and oppression against women and sexual dissidence constructed on the Internet as part of the strategies of an anti-gender movement or the movement against “gender ideology” sheds light on the scope of coercive memes beyond a reaction against the recognition of certain sexual dissidence rights or what Varela (2019) has called the fourth feminist wave, and Róvira Sáncho (2018) has dubbed the feminist evolution or feministization of social mobilizations. What is at stake is a moral project rooted in a neoliberal capitalist system which, as shown in this case, is also constructed based on forms of domination that use humor to create mythologies that help maintain a heteropatriarchal, binary gender order as the only possibility.

Emmelhainz (2016) uses the perspectives of Foucault and Brown, who consider “neoliberalism as a political and government rationality, and as a normative rationality that implies that power governs from a regime of truth that becomes common sense” (p. 19) to argue that:

The gradual implementation of neoliberal policies is inseparable from the introduction of neoliberalism as the common sense, sensitivity and affect of subjects. As a result, neoliberalism is a way of understanding the world and creating knowledge about it, in which pragmatism prevails to make decisions focusing on results and maximizing individual economic benefits... In other words, I regard neoliberalism as a sensitivity that operates on the most intimate desires, colonizing our dreams, cannibalizing our ideals and regurgitating them as strategies for social control (p. 40).

Elsewhere (Bárcenas Barajas, 2020, 2021, 2022), shows the centrality of religious, parliamentary and interreligious civil society actors to the configuration and advancement of anti-gender movements. Here, however, the analysis focuses on a key resource (the coercive meme) for a less explored type of actor, namely anti-gender5 ideological profiles, in other words, those which do not embody a specific person yet which perform the role of a political actor by exercising symbolic and representation power against “gender ideology”. For anti-gender ideological profiles, what is at stake is the rationalization of a heteropatriarchal gender order through symbolic, representational power, which takes shape in a resource such as memes. This acquires greater relevance during moments of tension and polarization of public opinion.

Consequently, this article, which is set in the Mexican context, seeks to analyze how the memes against feminism and sexual dissidence that circulate in anti-gender profiles or those opposing “gender ideology” constitute practices of symbolic domination that perpetuate modes of oppression. Following the semiological perspective of Roland Barthes, coercive memes are analyzed as mythologies, enabling us to focus on three of their ideological functions: distorting meaning, naturalizing, and depoliticizing. The methodological strategy is based on the analytical centrality of returning to the ethnographic archive after adopting a methodological strategy such as digital ethnography.

Mythological Structure of Coercive Memes

Myth, a key concept for anthropological thought and that of communication, has been explored by perspectives such as that of the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss (1968, 2002), who established the contrasts between mythical and scientific thought and by the philosopher Cassirer (1968), who identified the power of mythical vis-à-vis rational thought. However, the starting point for this analysis is the perspective of the structuralist semiologist Barthes (1999).

To reveal the mythological structure of coercive memes, it is necessary to establish a conceptual starting point around what is meant by a meme and the role played by humour in its construction and forms of circulation. The term “meme” was proposed by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene (1976) to name a capacity for imitation and cultural transmission. Since then, other conceptualizations have emerged to attempt to reveal the specific form it takes in digital contexts. Unlike Dawkins, Shifman (2014) considers that memes do not represent a single cultural unit with the capacity to propagate, but groups of content units.

Likewise, Wiggins (2019) posits that it is problematic to assume an analogous relationship between the Dawkinsian meme and the Internet meme because the former ignores the discursive faculty of the latter, whose essence is not determined by a capacity for imitation either. From his perspective, Internet memes are discursive units of digital culture that indicate an ideological practice that occurs in the stages of construction-through the selection of certain intertextual references-and circulation on various digital platforms (Wiggins, 2019). They are therefore not defined by imitation but by the agency to propose or counter a discursive argument through visual and verbal interaction, which is why they are inherent in a critical component of society (Wiggins, 2019).

If we consider, as Wiggins (2019) does, that the ideological function of memes focuses on restricting or guiding behavior in the ways preferred by the dominant group, it is possible to argue that anti-feminist and anti-sexual dissidence memes, such as those analyzed here, exploit a characteristic that enables them to expand and enhance their ideological function: humour and laughter.

The contributions of the critical approach to humor establish a distinction between coercive and rebellious humour. Whereas the former is repressive and serves to mock those outside social norms, the latter mocks and subverts established rules or conventions by questioning power relations (Drakett et al., 2018).

The centrality of coercive humor, which serves to perpetuate forms of domination and oppression such as those related to gender and sexuality, lies in the fact that, as Yoon (2016) notes, humour is one of the most pervasive elements of public culture and plays a central role in everyday interactions. Nowadays, due to the technological ease of creating them and the speed with which they circulate, Internet memes and their humourous content contribute to shaping daily life, which takes place between online and offline spaces, and between platforms and technologically mediated sociability, as noted in the studies conducted by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2020) and the Asociación de Internet MX (2021) for the Mexican case.

The ideological practice Wiggins (2019) highlights in the construction and circulation of Internet memes is essential to understanding them as a myth. For this reason, the theoretical, methodological, and analytical point of intersection posited lies in considering that coercive memes produce and tell myths, in other words, they construct mythologies about feminism and sexual dissidence. However, they are no longer only spread through narratives in which they are transmitted by word of mouth, but are characterized by other logics of production and circulation that increase their exposure thanks to the technological mediation made possible by social digital media such as Facebook, among other information and communication technologies.

For Cassirer (1968), the most important and alarming feature of the development of modern political thought is the emergence of a new power: the power of mythical thought (and its preponderance over rational thought). But what is a myth? Barthes (1999) defines it as speech, in other words, a message or communication system, meaning that it does not necessarily have to be oral, but can comprise written discourse, photographs, cinema, and advertising. Nowadays, Internet memes also constitute support for myths, and as such, they comprise a message or communication system.

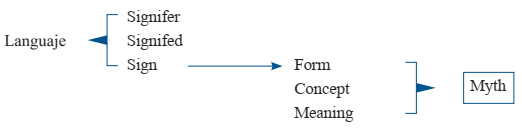

What are the particularities of myths? Barthes (1999) defines them as a metalanguage or second semiological system, in that the former consists of language, which comprises three elements: signifier, signified and sign (a meaning comprising the associative total of the first two terms). Myth also comprises these three elements but requires language because it is constructed on an existing semiological chain, and therefore the signs created through language become the signifier of myths.

This relationship between the first and second semiological system enables Barthes (1999) to state that myths do not arise from the “nature” of things and instead have a historical foundation provided by the language through which myth constructs its own system. To establish an analytical distinction, in myth, the signifier is called form, the signified concept, and the sign meaning (Barthes, 1999).

Source: Compiled by the authors based on the distinction between language and myth proposed by Barthes (1999).

Figure 1 Relationship between language and myth as semiological systems

Because form is constructed based on a sign, Barthes (1999) considers that it does not lose its meaning, and instead becomes impoverished by losing its value to contribute to a myth. For its part, the concept is historical and intentional. Its elements are linked by associative relationships. Through it, a new story is inserted into the myth (Barthes, 1999). Finally, as the link between form and concept, meaning constitutes the myth (Barthes, 1999).

Following Barthes’ proposal, it is possible to reveal the mythological structure of coercive memes, such as those against feminists and sexual dissidence, in which the form consists of the image or graphic composition. In it, meaning is impoverished, although not its historical roots, as happens with some of the images from “The Simpsons” used for these resources. Prior to that, they have their own meaning, anchored to a part of social and cultural history. The concept consists of the text that accompanies the image of the memes, through which it is given an intention and a new story is inserted into the myth. Finally, the meme comprises the text and the image, because the form and the concept constitute the myth.

Three (ideological) functions of myths are also taken up from Barthes’ proposal: distorting, naturalizing, and depoliticizing, which constitute the analytical categories on which this article is based. From Barthes’ perspective, myth has the function of distorting meaning to talk about things. It also depicts issues with a historical intention as being natural (Barthes, 1999):

By moving from history to nature, myth reduces things: it succeeds in abolishing the complexity of human acts, grants them the simplicity of essences, suppresses dialectics, and any improvement that goes beyond the immediately visible, and organizes a world without contradictions (p. 129).

For Barthes (1999), politics is a set of human relationships as regards their ability to construct the world. Therefore, from this perspective, myth, as a metalanguage, constitutes a depoliticized discourse that intervenes in an already naturalized background, in other words, one that has been stripped of its complexity and essence.

Back to the Ethnographic Archive: a methodological starting point

For Marcus (1998), the ethnographic archive constitutes a treasure trove of diverse materials that arise in the approaches adopted in field work. He even considers that every anthropologist is an archivist of their own career, which acquires forms of organization and storage, as well as consultation and reinterpretation practices. That is why he proposes an invitation to modify the perspective from which it is seen, to stop regarding it merely as a “primary source” and view it as a project of analytical knowledge.

This article takes up this invitation to establish a methodological starting point that makes it possible to reveal the feminist and sexual dissidence mythologies analyzed here, since the review and organization of the ethnographic archive was what triggered the analytical route that led to them.

The ethnographic archive created in light of a project on the anti-gender movements in Mexico and Brazil was organized through a triple anthropological anchorage in which ethnography in the public sphere, legal anthropology and digital ethnography converge (see Bárcenas Barajas, 2020). This led to the establishment of a typology of the main actors in the anti-gender movement: members of religious organizations, parliamentarians and interreligious civil society. However, as the field work progressed in the two countries, a new actor emerged: anti-gender ideological profiles, in other words, those who, without embodying a particular person (unlike the previous ones), positioned themselves against “gender ideology” through various symbolic and information resources.

For the research, two profiles against “gender ideology” in relation to the Mexican context were selected on Facebook. A common feature of the two pages is the defense of a neoliberal capitalist model and consequently a position against communism and socialism, as well as a position in favor of the unrestricted possession of firearms. They also share their support for both the ex presidents of the United States, Donald Trump, and Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, and their opposition to the incumbent president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The first ideological profile “Me lo contó un posmo 3.0” (A postmo told me about it 3.0) had 46 518 followers at the beginning of the ethnographic archive in June 2019, which had increased to 64 938 by April 2022. The second ideological profile, “La taberna antiprogre”, (The anti-progressive tavern) had 10 414 followers in June 2019. In September 2019 it was removed from Facebook because it contained hate speech. However, its support page, “La taberna antiprogre infinitum” in which part of its content was replicated daily, was kept, and by April 2022, it had accumulated 27 000 followers.

To conduct a detailed analysis of these ideological profiles, part of the field diary containing an ethnographic record of each of them was reviewed at the end of 2021, covering the period June 1 to August 31, 2019. It was prepared using the methodological foundations of digital ethnography in the modality known as the “one-way mirror approach” (Urbanik & Roks, 2020). From this perspective, Facebook represented not only a social medium, but also a place where cultural practices marked by meanings that guide action and the construction of significance take place.

The return to the ethnographic archive-two years later and with an analytical view strengthened by the previous approaches-made it possible to identify the centrality of a resource such as memes for anti-gender movements or those against “gender ideology” and to recognize the importance of a symbolic process in which anthropology and communication converge: the production of mythologies.

This occurred particularly in the “La taberna antiprogre” page, which is examined in this analysis because, in the case of “Me lo contó un posmo 3.0” from June 1 to August 31, 2019, 146 posts were uploaded, of which only 35 used a meme in their structure6. Only 16 of these were related to anti-feminism and opposing sexual dissidence. Conversely, in the case of “La taberna antiprogre”, from June 1 to August 31, 2019, 296 posts were uploaded, 151 of which, in other words, 51%, used a meme. Of these, 50 (a third) are anti-feminism and against sexual dissidence. However, two were posted twice, meaning that the corpus of analysis for this article comprised 48 memes: 31 related to anti-feminism and 17 to sexual dissidence.

Below, Table 1 shows the categories that enabled a classification to be established together with their frequency.

Table 1 Categories of antifeminist and anti sexual dissidence discourse in memes

| Anti-feminist memes | Memes against sexual dissidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Frequency | Category | Frequency |

| Patriarchal violence | 12 | Ridiculing trans gender identity | 5 |

| Ridiculing feminist identity | 9 | Heteropatriarchal violence | 4 |

| Criticism of feminist demands | 4 | Calling people unintelligent because of their use of inclusive language | 3 |

| Inconsistency in feminist positions in favor of abortion | 4 | Business and political opportunism during Pride Month | 2 |

| Violence in feminist protests | 2 | Mocking the neutral uniform initiative | 2 |

| Depicting actors against “gender ideology” as heroes | 1 | ||

Source: Compiled by the author.

In the anti-gender page analyzed, 31 memes related to anti-feminism and 17 against sexual dissidence were identified. They were classified on the basis of the five situations in Mexico City mentioned below.

But what happened in Mexico City during the three months of the ethnographic record? What is the importance of the period of time analyzed? Below is a brief timeline.

On June 3, 2019, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum launched the “Neutral Uniform” program. Although the measure sought to make it no longer compulsory for junior high school girls to wear skirts as part of their school uniform, to promote equality between girls and boys, certain neoconservative sectors, such as the Mexican Family Council, regarded it as a means of ideologizing boys by encouraging them to wear skirts.

On June 12, 2019, La Salle University prevented the conference on “Deconstructing radical feminism, gender ideology and abortion” from being held on its premises. It had been scheduled to be given by Agustín Laje and Nicolás Márquez, the authors of El libro negro de la nueva izquierda. Ideología de género or subversion cultural, who were on tour in various cities in Mexico at the initiative of the Mexican Family Council. La Salle University made this decision as a result of the criticisms, disagreements and questions voiced on social media such as Facebook and Twitter about the fact that this event was to be held at an institution dedicated to the production of knowledge, where the value of science and diversity is recognized.

On July 30, 2019, Ophelia Pastrana, a comedian and YouTuber, suffered an act of discrimination due to her gender identity in a Mexico City café. This polarized public opinion, expressed on social media such as Twitter and Facebook, around trans identities.

On August 5, 2019, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation endorsed the 2016 Official Mexican Standard (NOM) ordering all public hospitals to terminate pregnancies resulting from rape, for which only a prior written request under oath would be requested from the person affected. Health personnel are therefore not obliged to verify what the applicant has declared.

On August 16, 2019, in several cities in Mexico, as well as the capital, a march was held with the slogan #NoMeCuidanMeViolan (#TheyDon'tProtectMeTheyRapeMe), with demonstrators protesting against cases of violence against women by members of the police force. As part of the demonstrations, in Mexico City, public transport stations, buildings and historical monuments were burned and painted, including the emblematic Angel of Independence on Paseo de la Reforma. As a result, social media and the mass media criminalized the feminist protest and perceptions of the movement were polarized.

Ideological Functions of Memes: distorting, naturalizing and depoliticizing

Following Barthes’ perspective, three ideological functions of coercive antifeminist memes and others opposing sexual dissidence are analyzed below: distorting, naturalizing, and depoliticizing, which produce mythologies favorable to a neoliberal sensitivity.

With regard to the first ideological function-distorting meanings- it is essential to begin with the fact that when memes are created, intertextuality7 plays a key role in producing meaning. However, in the case of coercive memes, such as antifeminist ones or those opposing sexual dissidence, it is more accurate to argue that this is distorted in that they create mythologies.

As a result of the analysis conducted, one can say that in the coercive memes related to antifeminist, the meaning of patriarchal privileges is distorted when attempts are made to associate them with economic privilege, which implies that the former are a lie or fantasy, since not all men have the same purchasing power. However, patriarchy is experienced as embodied meaning, in that regardless of a man’s financial status, the power that creates it is exercised through various violent macho acts against women.

Regarding feminism, it was observed, on the one hand, that demands related to the empowerment of women and gender parity are depicted as a matter of expediency to obtain advantages or privileges over men. A similar situation occurs with mansplaining, which is construed as a means for women to portray themselves as victims. Conversely, a direct relationship was established between feminism and violence in demonstrations in public spaces, such as those related to femicides or associated with the hashtag #nomecuidanmeviolan, in which monuments, historic buildings and public transport stations were destroyed, painted, or burned in protest.

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 1 “Violence is the only way for us to be heard”. “Stop violence against women”.

Creating mythologies about feminist identities occurs through a power of attorney expressed by ridiculing certain aesthetics related to fatphobia, hair dyed bright colors, and the exercise of violence towards other women who hold different opinions, such as those who defend life from the point of conception, which, in turn, makes it possible to show the alleged incoherence of feminism.

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 4 “We feminists defend women!” Two minutes later... “How come you don´t support abortion? I hope they rape and kill you; you freak!” #FeminismoEsContradicción

The trans gender identity is used to reinforce this inconsistency regarding the recognition of a fundamental right such as abortion. For this reason, phrases such as the following are used, in which trans identities serve as a means of ridiculing women’s autonomy over their bodies: a) “You are a man, you can’t have an opinion on abortion”. “Are you assuming my gender? You are a transphobic reactionary”; b) “A man cannot have an opinion on abortion”. “What a coincidence, I identify as a woman”.

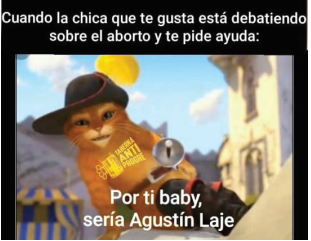

In contrast to the ridiculing of feminist identities, the construction of an ideal of feminine identity in relation to women’s role as partners was also identified. This can be seen in memes with phrases such as: a) “when the girl you like posts more homophobic, sexist memes than you… one day you will be my wife”; b) “when she wants to kiss you with that mouth that uses inclusive language” (expression of remoteness and disgust in the photograph of the man in the image in the meme); and c) when the girl you fancy is thinking about abortion and asks you for help... “for you baby, I would be Agustín Laje”.8

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 5 When the girl you fancy is thinking about having an abortion and asks you for help: For you, baby, I would be Agustín Laje”.

In coercive memes opposing sexual dissidence, mythologies are constructed about trans identities when their configuration in relation to a sex-gender system is ignored and they are presented as the result of a wish, a whim, or an inconsistency, which leads to ridicule through phrases such as, “Today I identify as a unicorn”. Likewise, the meaning of inclusive language is distorted when those who use it are characterized as lacking in intelligence and common sense.

Finally, in relation to the neutral uniform initiative, the use of images in which boys are wearing skirts and, in some cases, a green scarf, was identified, as well as letters in rainbow tones to contrast them with the clothing of male revolutionaries of other times. This results in a contrast between a historically constructed imaginary based on masculinity and masculinities which, from their perspective, attempt to create what they call a progressive ideology.

Fuente: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 6 “History books will talk about this, how embarrassing”. “Revolution for Freedom 2019”

Analyzing the second ideological function-the naturalization of a gender order-requires recognizing the centrality of the configuration of an androcentric, heteropatriarchal culture, anchored in the gender binary, to essentialize the identities of men and women.

In antifeminist coercive memes, this naturalization or normalization of patriarchal violence is exercised through insults towards women, as well as the normalization of their identities through the validation of historically assigned gender roles, restricted to the domestic sphere. But the naturalization of patriarchal violence is also visible in the mockery of men who are recognized as feminist allies, deconstructed or pro-abortion. Although feminisms have criticized the position and prominent role certain men play in mobilizations and causes related to women’s rights-rather than recognizing their privileges and breaking patriarchal pacts-in these cases, the purpose is linked to depicting a patriarchal, macho masculinity as one that it correct in the natural order of things.

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 8 “A feminazi calling me an oppressive macho”. “Me freaking out because the dishwasher is talking”.

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 9 “The guy who maintains his masculinity and does not go around posing as a feminist ally”.

In coercive memes against sexual dissidence, a naturalization of gender can be observed when trans identities are ridiculed on the grounds that gender is determined by sex. According to the specialist in psychiatric ethics, Giordano (2018), this can be explained by the fact that “the way we see biological facts is filtered by our assumptions regarding how people should be” (p. 108). However, various gradations that prevail in the spectrum from male to female make it possible to identify more than two sexes and genders:

There are at least twelve other chromosomes in the entire human genome regulating sexual differentiation, and thirty genes involved in sexual development... It could be argued, of course, that only two traditionally identified sexes are healthy, and that all the others are pathological. But there is no empirical fact based on which we can identify what is “healthy” and what is “pathological” sex (Giordano, 2018, pp. 107-108).

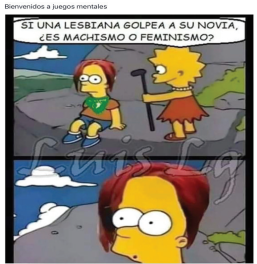

Likewise, the biological nature of human reproduction and the essentialization of feminine and masculine identities leads to heteropatriarchal violence being perpetrated in memes in relation to reproduction between same-sex couples and the naturalization of gender roles, without considering sexual orientation, gender identity or expression.

Source: La taberna antiprogre.

Figure 10 If a lesbian hits her girlfriend, is it machismo or feminism?

In short, it is possible to propose two goals of naturalization as an ideological function of mythologies about feminism and sexual dissidence:

Validating a heteropatriarchal gender order against what they call progressive ideology, a “gender ideology”, to legitimize forms of domination and oppression of women and sexual dissidence that are useful for a neoliberal capitalist system.

Confronting and delegitimizing the scientific thinking that depathologized non-heterosexual sexual orientations and trans gender identities, based on a reductionist, hegemonic vision of both biological reproduction and the sex-gender relationship. Consequently, the gender binary is framed as a regime of irrefutable truth, in that it shapes the common sense used by the neoliberal sensibility described by Emmelhainz (2016).

Finally, in relation to the third ideological function-depoliticizing rights-if we consider, together with Cassirer (1968), that the myth “is an objectification of man’s social experience, rather than his individual experience” and that in this objectification, an emotion is expressed (Cassirer, 1968), it is possible to argue that the distortion of meaning and the naturalization of a gender order that occurs through feminist mythologies and sexual dissidence impact the configuration of impressions and the economy of emotions, as proposed by Ahmed (2015), which gives rise to the depoliticization of rights that have been fought for by feminisms and sexual dissidence movements.

But how does this process occur? In the first place, it is necessary to consider that, as has been shown, some demands promoted by feminism are represented as an advantage or a way of obtaining privileges over men. The right to abortion is depicted as an inconsistency for feminism itself, while trans identities are associated with a whim or desire and the use of inclusive language as a lack of intelligence or common sense, at the same time as various forms of heteropatriarchal violence are naturalized.

Secondly, it is worth noting that in 40 of the 48 selected memes, the reaction “it amuses me” was the most frequent one and that even though there are fewer memes against sexual dissidence than feminism, the former exceeded the latter by 1 032, meaning that coercive memes against sexual dissidence are found more “amusing” in the ideological profile analyzed.

According to Askanius (2021), those that:

...share a laugh at the expense of an “outgroup” foster greater social affiliation and decrease social distance from their “ingroup” while increasing social distance from their targets of ridicule and insult through a process of dehumanization (p. 152).

Table 2 Interaction and circulation of memes against feminism and sexual dissidence

| Theme | Amount | Reactions | Comments | Shared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antifeminism | 31 | 4 858 | 533 | 3 249 |

| Sexual dissidence | 17 | 5 890 | 448 | 3 211 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

Likewise, it is important to note that, as shown in the table presented above, even though the number of memes about antifeminist is twice that of those related to sexual dissent, the difference between the number of times these contents were shared is minimal.

If emotions are set in train through the circulation of objects -objects of emotion- through “sticky” associations between signs, figures, and objects, saturated with affect, as sites of personal and social tension (Ahmed, 2015), it is possible to argue that memes against feminist and sexual dissidence constitute an object of emotion, whose ideological functions are enhanced through coercive humour. Accordingly, the mythologies they produce create impressions that affect those who are oppressed or dominated by them, but not in relation to individual identities, but rather to subjectivities, in this case, feminist subjectivities or sexual dissidence. Through them, a differentiation process also occurs that impacts the depoliticization of various rights, as happens with women who do not wish to be identified as feminists to distance themselves from representations such as those expressed in the mythologies presented above or in right-wing lesbian, gay and trans people.

According to Barthes (1999), politics implies a set of human relationships in its power to construct the world. If we consider that nowadays the guarantee of rights for women and sexual dissidents plays a fundamental role in achieving this purpose, the analysis of the aforementioned coercive memes shows that the representations and humorous devices used contribute to the depoliticization of the right of women and girls to a life free of violence (hetero-patriarchal and sexist), the right to non-discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, the right to decide over one’s own body in relation to reproductive autonomy (abortion), sexuality and the free development of one’s personality.

Final thoughts

This article analyzed the role of an actor rarely studied by anti-gender movements: ideological profiles opposing “gender ideology” through a resource such as coercive memes, both those against feminism and sexual dissidence.

The approach presented proposes a theoretical-analytical approach to the mythological structure of the memes called coercive memes here, which made it possible to establish three analytical categories through the following ideological functions: distorting meaning, naturalizing the gender order and depoliticizing rights.

This approach-whose methodological starting point is the return to the ethnographic archive-enabled us to identify the depoliticization of central rights for feminism and sexual dissidence, since they are depicted as an inconsistency, advantage or privilege, a whim or desire, a lack of intelligence or common sense, as well as contradicting what is established by nature.

This finding allows us to state that the representations indicated above contribute to shaping the ways of perceiving, understanding and grasping the world, through which neoliberalism is established as common sense, sensitivity and affectivity (Emmelhainz, 2016), thereby perpetuating forms of oppression of groups that have historically been discriminated against, stigmatized and made invisible, such as women and sexual dissidents.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, S. (2015). La política cultural de las emociones. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de Género. [ Links ]

Askanius, T. (2021). On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: Exploring the humor-hate Nexus at the intersection of neo-nazi and Alt-Right movements in Sweden. Television & New Media, 22(2), 147-165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982234 [ Links ]

Asociación de Internet MX. (2021). 17° Estudio sobre los Hábitos de los Usuarios de Internet en México 2021. https://cutt.ly/4GXMasJ [ Links ]

Bárcenas Barajas, K. (2020). Tres anclajes antropológicos sobre la politización evangélica contra la “ideología de género” en México y Brasil. En M. A., López Leyva (Ed), Perspectivas contemporáneas de la investigación en Ciencias Sociales (pp. 247-280). Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Bárcenas Barajas, K. (2021). La violencia simbólica en el discurso sobre la “ideología de género”: una perspectiva desde la dominación simbólica a través del pánico moral y la posverdad. Intersticios sociales, (21), 125-150. https://doi.org/10.55555/IS.21.319 [ Links ]

Bárcenas Barajas, K. (2022). Introducción: coordenadas de los movimientos antigénero en América Latina. En K., Bárcenas Barajas (Ed). Movimientos antigénero en América Latina: cartografías del neoconservadurismo (pp. 7-43). Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Barthes, R. (1999). Mitologías. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Bonet-Martí, J. (2020). Análisis de las estrategias discursivas empleadas en la construcción de discurso antifeminista en redes sociales. Psicoperspectivas, 19(3), 52-63. https://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psico-perspectivas-Vol19-Issue3-fulltext-2040 [ Links ]

Cassirer, E. (1968). El mito del estado. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Drakett, J., Rickett, B., Day, K. & Milnes, K. (2018). Old jokes, new media-Online sexism and constructions of gender in Internet memes. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 109-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0959353517727560 [ Links ]

Emmelhainz, I. (2016). La tiranía del sentido común. La reconversión neoliberal de México. Paradiso Editores. [ Links ]

García, L. & Bailey, O. (2020). Memes de Internet y violencia de género a partir de la protesta feminista #UnVioladorEnTuCamino. Virtualis, 11(21), 109-136. https://www.revistavirtualis.mx/index.php/virtualis/article/view/337/383 [ Links ]

Ging, D. & Siapera, E. (Eds.) (2019). Gender hate online: Understanding the New Antifeminism. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Giordano, S. (2018). ¿Qué sería del mundo sin sexo? Reflexiones sobre el sexo y el desarrollo de género. En P. Capdevielle y M. Medina (Eds), Bioética laica. Vida, muerte, género, reproducción y familia (89-116). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas. [ Links ]

Hakoköngäs, E., Halmesvaara, O. & Sakki, I. (2020). Persuasion through bitter humor: Multimodal discourse analysis of rhetoric in internet memes of two far-right groups in Finland. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120921575 [ Links ]

Harvey, A., Thompson, S., Lac, A. & Coolidge, F. (2019). Fear and derision: a quantitative content analysis of provaccine and antivaccine internet memes. Health Education & Behavior, 46(6), 1012-1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119866886 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2020). Encuesta Nacional sobre Disponibilidad y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información en los Hogares (ENDUTIH) 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/dutih/2020/#Tabulados [ Links ]

Iturralde, E. (2021). El trolling y las expresiones de odio como prácticas de validación de identidad en línea en usuarios de Facebook [Tesis doctoral, UNAM]. TESIUNAM. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2021/febrero/0809456/Index.html [ Links ]

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1968). Mitológicas. Lo crudo y lo cocido. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Lévi-Strauss, C. (2002). Mito y significado. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Marcus, G. (1998). The once and future ethnographic archive. History of the Human Sciences, 11(4), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/095269519801100404 [ Links ]

Nagle, A. (2017). Kill all Normies. Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Zero Books. [ Links ]

Róvira Sáncho, G. (2018). El devenir feminista de la acción colectiva: las redes digitales y la política de prefiguración de las multitudes conectadas. Teknokultura, 15(2), 223-240. https://doi.org/10.5209/TEKN.59367 [ Links ]

Ruocco, J. (2020). Cómo la extrema derecha se apoderó de 4chan. Nueva Sociedad, (286), 25-34. https://nuso.org/articulo/como-la-extrema-derecha-se-apodero-de-4chan/ [ Links ]

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press. [ Links ]

Urbanik, M. & Roks, R. (2020). GangstaLife: Fusing Urban Ethnography with Netnography in Gang Studies. Qualitative Sociology, 43, 213-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-020-09445-0 [ Links ]

Varela, N. (2019). Feminismo 4.0. La cuarta ola. Ediciones B. [ Links ]

Villar-Aguilés, A. & Pecourt Gracia, J. (2021). Antifeminismo y troleo de género en Twitter. Estudio de la subcultura trol a través de #STOPfeminazis. Teknokultura, 18(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.70225 [ Links ]

Wiggins, B. (2019). The discursive power of Memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality. Routledge. [ Links ]

Yoon, I. (2016). Why is it not just a joke? Analysis of Internet memes associated with racism and hidden ideology of colorblindness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 33, 92-123. http://www.jcrae.org/journal/index.php/jcrae/article/view/60 [ Links ]

1Project funded by the Support Program for Research and Technological Innovation Projects (PAPIIT), UNAM.

2For details on the emergence and expansion of anti-feminism since the second half of the 19th century, through its links with the new American Christian right movement, to contemporary approaches related to “gender ideology”, see Bonet-Martí (2020).

3“Gender ideology” is a term created by the Catholic Church hierarchy, appropriated in recent years by evangelical actors, to refute one of the main premises of contemporary gender theory: the fact that the sex-gender system is part of a sociocultural construction with patriarchal purposes. This term attempts to legitimize a gender essentialism that begins with a biological conception of sex, from which the complementarity between women and men is established on the basis of a set of traditional gender roles as the sole form of organizing and structuring society as the only valid means of organizing and structuring society (Bárcenas Barajas, 2021, p. 127).

4This campaign was copied in Mexico by the Mexican Family Council, an organization that orchestrated the circulation of the so-called “freedom bus” with transphobic slogans and others against what they call “gender ideologies”.

5These ideological profiles differ from “trolls” although they share two of their characteristics: anonymity and the propagation of inflammatory discourse (Iturralde, 2021). No other practices of this phenomenon were observed, such as trolling other users, the algorithmic mechanics of websites where they interact, or platform developers and owners (Iturralde, 2021), or “gender trolling” practices, such as credible threats, publishing personal information or doxxing (Villar-Aguilés & Pecourt Gracia, 2021).

6In both ideological pages, the use of other types of resources was identified: texts focusing on criticism and governments described as progressive in relation to the gender agenda, misinformation based on fake or decontextualized news; positions against a particular right on the feminist or sexual dissidence agenda and publications with a religious reference (Catholic or evangelical Christian).

7Procedure whereby references comprising a text are chosen and juxtaposed with an image or graphic reference, to create a meme.

8One should recall that in one of the memes of Agustín Laje and Nicolás Márquez, two of the best-known, most influential anti-gender figures in Latin America, are depicted as having a certain heroism.

How to cite: Bárcenas Barajas, K. (2023). Feminist and Sexual Dissidence Mythologies: distorting meaning and depoliticizing through humour. Comunicación y Sociedad, e8452. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2023.8452

Received: May 16, 2022; Accepted: July 04, 2022

texto en

texto en