Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub Oct 03, 2022

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.7841

Articles

General theme

When attack meets debate. Presence of conflict in the framing of the 2018 and 2021 Mexican federal elections

1 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México. carlos.munizm@uanl.mx

During election campaigns, the mass media favor political debate, giving relevant issues a particular framing. In this coverage the use of the conflict frame stands out, and although it usually presents politics as an exercise of confrontation and attack, it can also show it as a process of discussion and the exchange of opinions. A content analysis was conducted on television and press news during the 2018 presidential and the 2021 federal legislative elections in Mexico. The findings confirm the existence of two differentiated frames, that of “conflict” and that of “discussion and political agreement”. Furthermore, a connection between the two frames was detected in the media coverage of the campaigns.

Keywords: Framing; conflict; election campaign; press; television; Mexico

Los medios favorecen el debate político durante las campañas electorales, dando un tratamiento informativo particular a los asuntos relevantes. En esta cobertura destaca el uso del encuadre de conflicto que, aunque suele presentar la política como un ejercicio de confrontación y ataque, también puede mostrarla como un proceso de debate e intercambio de opiniones. Se realizó un análisis de contenido de las noticias de televisión y prensa durante las elecciones presidencial de 2018 y federal de 2021 en México. Los hallazgos confirman la existencia de dos encuadres diferenciados de “conflicto” y de “debate y acuerdo político”, detectándose en ambas campañas la conexión existente entre ambos en la cobertura mediática de las elecciones.

Palabras clave: Framing; conflicto; campaña electoral; prensa; televisión; México

Os meios de comunicação privilegiam o debate político durante as campanhas eleitorais, dando especial tratamento informativo aos temas relevantes. Nessa cobertura, destaca-se o uso do enquadramento do conflito, que, embora tenda a apresentar a política como um exercício de confronto e ataque, também pode mostrá-la como um processo de debate e troca de opiniões. Uma análise de conteúdo das notícias da televisão e da imprensa foi realizada durante as eleições presidenciais de 2018 e federais de 2021 no México. Os resultados confirmam a existência de dois enquadramentos distintos de “conflito” e “debate e acordo político”, detectando em ambas as campanhas a ligação entre os dois na cobertura mediática das eleições.

Palavras-chave: Framing; conflito; propaganda eleitoral; televisão; México

Introduction

The media play a crucial role in transmitting political information, and the coverage they provide enables a necessary connection to be made between politicians and rulers and the citizenry, to the point that it is often claimed that this coverage works as a currency or as a tool that democracies can use to establish themselves (Gerth & Siegert, 2012). This is due, to a large extent, to the fact that a healthy democracy requires the existence of a public that is well informed about political issues (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). According to this argument, the media have become a crucial source of information (Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006), especially during election campaigns, when media dependency of citizens tends to increase (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Ergün & Karsten, 2019).

The media transmit program proposals by covering electoral processes on their newscasts, as well as giving the different positions of the contenders on important issues: vital information for citizens to be able to make their own decisions and to become involved in politics in an effective manner (Matthes, 2012). To this end, the journalistic practice of covering events is crucial, giving the news a particular treatment or framing to present the issues relating to the campaign (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2013; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006). In line with what Entman (1993) proposed, this process involves selecting “some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (p. 52).

The framing implies, therefore, selecting certain news frames to structure the information and to provide it with meaning (de Vreese, 2012; Matthes, 2012). A journalistic practice that in the context of election campaigns denotes the way in which the candidates’ and the parties’ proposals, discussions and strategies are narrated on the news, emphasizing or excluding possible approaches to the existing reality (Gerth & Siegert, 2012; Muñiz et al., 2018; Rodelo, 2020; Schuck, 2017). It has been found that the media tend to emphasize certain approaches for presenting politics (Gronemeyer et al., 2019; Schuck, 2017; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006), and the conflict frame stands out among them (Ergün & Karsten, 2019; Muñiz et al., 2018). This frame has been perceived as a journalistic approach inherent to political coverage (de Vreese, 2014; Schuck et al., 2016), that underscores confrontation and disagreement between the political actors and often results in an unfavorable treatment of politics, since it is associated with attack and reproach (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Galais, 2018; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000; Trussler & Soroka, 2014).

But in contrast of this idea of conflict in association with negativity, other authors have advanced that it is better to conceive of the framing as a manifestation of conflict in the form of political debate (Lengauer et al., 2012; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016). Political coverage can then be set out in terms of a substantive conflict, focused on political and ideological ideas, issues and values (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Colvin et al., 2020) or in terms of a framing of consensus, or discussion, and political agreement, where information is given about the confrontation of opinions in their quest for consensus, agreement, compromise or cooperation in order to solve problems (Muñiz et al., 2018; Walgrave et al., 2018).

Bearing in mind this reality, as reported in the existing literature, the present article seeks to analyze the framing of conflict, both from the traditional approach that links it to attack and reproach, and from the approach that presents it as a political debate or agreement, used by the traditional mass media -the press and television- to cover the 2018 presidential election campaign and the 2021 campaign for election to the federal Chamber of Deputies in Mexico. It is worth mentioning that the 2018 election meant the arrival to the presidency of a candidate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, openly connected with the left, who had broken away from the power of the traditional parties (Martínez Garza & Maltos, 2019). In this sense, it is worth comparing the two campaigns in order to determine whether López Obrador’s obtaining the presidency, and the policies he followed during his three years of government, might have resulted in some changes being made to the informative framing offered by the media in the two electoral processes.

Media framing of politics

Attaining a smooth running of the democratic system is to a very large extent closely connected with the existence in this system of a public that is well informed about political issues, as well as with how the different actors that make up the country’s political system perform in respect of this public (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). In this process of constructing the citizenry’s political knowledge, the mass media play a crucial role since they are an essential source of political information for a large portion of the population (Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006), and this is so both for the traditional media and for the social media. Although this relationship is also established during non-electoral or government periods, it is during election campaigns that the citizens’ media system dependency increases (Ergün & Karsten, 2019; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006), since there is a greater need for guidance in order to make informed decisions having to do with the citizens’ political participation (Bjarnøe et al., 2020).

At these times, the work of politicians, candidates and parties to establish their points of view about reality, is intensified, with the creation of a relationship between the media and the politicians in which the frames of these two actors compete to position themselves within the informative text (Gerth & Siegert, 2012; Rodelo, 2020). In this context, it is necessary for the media to try to attain the greatest neutrality and objectivity possible when it comes to presenting politics, and avoid media biases, mainly because it is during election campaigns that the audience pays the most attention to political coverage of the news, and it can therefore develop more critical attitudes towards possible media biases perceived in journalistic work (Ergün & Karsten, 2019). This activity implies the production of information that comes from a process of selecting which issues are to be given greater relevance or salience, and excluding others (Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016).

Nevertheless, this professional exercise does not end with the selection of relevant issues; in addition, information needs to be structured through certain frameworks or approaches that will provide a particular informative treatment or framing of reality (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). This process implies selecting frames within the message to highlight certain aspects and considerations that are maintained concerning issues or events in the political debate (Bartholomé et al., 2018) or in the informative field of the media (de Vreese, 2012; Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Gerth & Siegert, 2012; Muñiz et al., 2018). Not surprisingly, framing is presented as an essential mechanism within journalistic work; because it is impossible to avoid using certain news frames at the moment of producing the news stories (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Entman, 1993; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006).

The significance of framing within journalistic practice makes it extremely important to analyze the way in which the media, via their informative coverage, present political issues and processes (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). In this regard, a large number of studies have been carried out using the theory of framing to analyze the news frames employed in the media to present political information, above all during electoral periods (Rodelo, 2020; Schuck, 2017; Schuck et al., 2013). Specifically, in this treatment or framing of the news, several frames usually stand out, among them that of conflict framing (Ergün & Karsten, 2019; Muñiz et al., 2018; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006). This frame has become an essential part of the presentation of information on politics, and is one of the most abundant and widely adopted frames in the media (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Galais, 2018; Schuck et al., 2016), often used to present politicians in an unfavorable light, as well as for showing the more negative side of politics (Trussler & Soroka, 2014).

That is why it is not surprising that this frame has been widely evaluated in papers about framing in electoral processes (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). However, analysis of the frame involves complex work, because it is a construct with different levels of application. This has usually led to working with inconsistent operational definitions, because it is hard to reduce the substantivity of the construct to a single angle (Bartholomé et al., 2018). In this sense, it has been advanced that, due to the substantivity of the conflict, it is a reality that can be approached using different frames. For example, Colvin et al. (2020) explain that there is a substantive conflict as distinct from other dysfunctional conflict, focused on conflictive and uncivil relations between groups. In turn, Bartholomé et al. (2018) differentiate between a non-substantive conflict frame and a substantive one centered on political and ideological ideas, issues and values.

On the other hand, it has also been proposed that the conflict needs to be distinguished according to the nature of the political reality reported. In this sense, it is claimed that there is a conflict frame that focuses on disagreement and confrontation between the actors, as opposed to the consensus frame that is more centered on the discussions of these actors with the aim of reaching an agreement and cooperation (Lengauer et al., 2012; Walgrave et al., 2018). In other words, the assumption is made that rather than there being one frame with two dimensions, there are two clearly differentiated frames and that they represent two unlinked realities. This is the case of the premise followed by Muñiz et al. (2018), who differentiate the conflict frame from the debate and political agreement frame. On the contrary, other authors perceive them as two extremes of the same bipolar concept (Lengauer et al., 2012), assuming that the conflict is usually a precedent of consensus (Schuck et al., 2016). Before going into detail on the peculiarities of each of the frames found in the literature, the following research questions are posed for resolution in view of this disparate conception of the frame:

Use of the conflict frame in political coverage

It is common for informative contents to use the conflict frame to deal with public issues (de Vreese, 2012; Schuck et al., 2013; Semetko & Valenburg, 2000), whether covering government performance or election campaigns (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Schuck, 2017). Without a doubt, this special use of framing results from the fact that conflict is an unavoidable and inherent part of politics, to such an extent that it has become a major ingredient of the media coverage of politics (de Vreese, 2014; Schuck et al., 2013). In fact, political conflict is an essential part of democracy, since its use contributes to the exchange of ideas between the different political actors, in their constant struggle for determining what the best choice is for attaining the development of society (Bartholomé et al., 2018).

Maybe one of the most widely accepted definitions of the conflict frame is the one posited by Semetko and Valkenburg (2000), who explain that this approach is used in the news to highlight the “conflict between individuals, groups, or institutions as a means of capturing audience interest” (p. 95). Their definition presents two dimensions: one of these concerns the description of the conflict and the other refers to the reasons for its use in the media. In this sense, conflict refers to disagreement, disputes and the confrontation between at least two points of view or positions on an issue, and the effects that the decision eventually made on this matter will have on society (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Colvin et al., 2020; Galais, 2018; Lengauer et al., 2012). A discrepancy that may result in attacks and even in reproaches by the different actors (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000).

On the other hand, an explanation of the journalistic use of the conflict frame in the media might be found in different factors. Without a doubt, negativity is one of the news values in informative messages, which is due to a large extent to the fact that it is an attractive approach, and that there is a great demand for it in a large portion of the audience (Trussler & Soroka, 2014). This aspect is closely connected with conflict (Lengauer et al., 2012; Trussler & Soroka, 2014), and this causes this frame to be used for the high newsworthiness of conflict and for the ability of the frame to turn the information into something more relevant for the media (Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016), but it is also highly attractive and interesting for the public (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Galais, 2018; Schuck et al., 2016). This is due to the fact that the reported aggressiveness brings emotion to the topic, which causes the likelihood of its making an impact on the audience to increase (de Vreese, 2014; Lengauer et al., 2012; Schuck et al., 2016; Trussler & Soroka, 2014).

In addition, it has also been pointed out that this use of the conflict frame can be explained rather as a journalistic routine, that produces information by juxtaposing the statements made by some political actors with those of others (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Trussler & Soroka, 2014). In this way, the use of conflict can help information to be more objective and better balanced, as well as preventing political bias in the news when presenting different views on the issue reported (Ergün & Karsten, 2019; Schuck et al., 2016). However, this expectation can be thwarted if political coverage slides unnecessarily towards highlighting agitation, political attacks and reproaches, since coverage like that will contribute to increasing a perception of institutional crisis (Gronemeyer et al., 2019) and result in negative effects for the citizenry and the democratic system itself (Bjarnøe et al., 2020).

At any rate, the conflict frame is one of the most commonly used in the media, especially to cover election campaigns (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Lengauer et al., 2012; Schuck et al., 2013; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006). In the Latin American context, Gronemeyer et al. (2019) have detected that it was the most frequently used frame in the political coverage of the Chilean press. In respect of the Mexican case, Lozano et al. (2012) point out that, starting in the 1990’s, the informative media dedicated a large portion of their electoral coverage to attacking and discrediting, instead of informing the audience of the issues and proposals. Also in the Mexican electoral context, Muñiz et al. (2018) detected that the conflict frame was one of the most used frames in the 2015 Nuevo León campaign, with more presence in the press than on television.

The debate and political agreement frame within political information

Although conflict framing has often been linked with negativity and incivility in the political arena, it should be remembered that when dealing with political information, a more discrete dimension of negativity can also be manifested. Here it is assumed that conflict does not necessarily have to imply negative coverage, as it can also be understood as a confrontation between different ideas and positions in connection with an issue (Lengauer et al., 2012; Schuck et al., 2016). This way, the conflict is circumscribed rather to the realm of contrasting different ideas and positions within the public debate among the various actors that make up the political system (Mazzoleni, 2010), which is essential for democracy to run smoothly (Bartholomé et al., 2018). For example, Schuck et al. (2016) conceptualize it as a “natural feature of democracy” (p. 190) since it is a component that is inherent to politics and democracy (Bjarnøe et al., 2020).

In this sense it is assumed that the journalistic use of conflict may have positive effects by providing the citizenry with information they need to take decisions, thus promoting a healthy skepticism (Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Colvin et al., 2020; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016). This is especially important during election campaigns, where it has been possible to detect that the presence of conflict framing focused on debate and the exchange of opinions on political issues or measures may contribute to the citizens’ political involvement (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Bjarnøe et al., 2020; Lengauer et al., 2012; Schuck et al., 2016). Thus, conflict is a previous and necessary step for consensus and decision-making to solve problems (Schuck, 2017; Schuck et al., 2016), contributing to the visualization of the debate as an essential formula for settling political controversies (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2013).

Despite this, studies on political communication have traditionally operationalized the conflict frame, by highlighting disagreement between actors and even the attacks and reproaches made by some actors against others (Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). In view of this reality, other authors such as Bartholomé et al. (2018) state that conflict should not be limited to a vision that links it to a generally negative tone in the news, and they emphasize civil and courteous political deliberation in its operationalization. A position shared by other authors, who state that in measuring the conflict it should be observed to what extent the news is presented as a political debate seeking consensus and cooperation, through a discourse that emphasizes a confrontation between opinions on at least two positions in order to reach an agreement, settle disputes, cooperate or even to achieve a reconciliation (Lengauer et al., 2012; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016).

The studies carried out so far on the substantive conflict frame (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Colvin et al., 2020) or consensus frame (Lengauer et al., 2012; Walgrave et al., 2018) show that there is a tendency to use the frame more in non-electoral times, when coverage of the arguments debated tends to have less substantivity and depth. Whereas in electoral times it is used less, when the news usually show a higher rate of attacks, disputes, incivility and political strategy (Bartholomé et al., 2018; Gronemeyer et al., 2019). In the case of Mexico, Muñiz et al. (2018) detected that the debate and political agreement frame was less common than the conflict frame, and no substantial differences were observed between its use by the press and on television. This is the only reference to the difference between the media that was found, although it is limited to a single local electoral process, in this case that of the Mexican state of Nuevo León in 2015. Bearing this in mind, the following research questions were posed:

RQ3: Were there any differences between press and television in terms of the use of the two frames?

RQ4: Were there any differences between the two election campaigns in the use of the two frames?

RQ5: To what extent did the year of the election campaign moderate the use of the two frames by the media?

Method

Sample and units of analysis

Considering the research questions set out above, a quantitative content analysis was conducted on the news stories published by the press and transmitted by television during the 2018 election campaign for the presidency, and the 2021 election campaign to the federal legislature in Mexico. For both campaigns, the news corpus was determined from a systematic random sampling of the different months of the election campaign. This kind of sample selection has been common in elections such as those studied here, that last for several months, as opposed to other campaigns such as those in Europe, which are much shorter and only last a few weeks. This fact represents a methodological challenge in terms of obtaining the sample, since in contrast to short electoral campaigns where it is possible to work with just a census of news, in a long campaign a representative sample must be sought over time. It is worth mentioning that only weekdays were reviewed, that is, from Monday to Friday, taking into consideration that at weekends there were no television news broadcasts.

In the case of the 2018 election campaign, the corpus collection based on the peculiarities of the Mexican election campaign was conducted in two stages. According to researchers, Mexican election campaigns usually occur in three different phases (Freidenberg & González Tule, 2009): two to start with, corresponding to the earliest months and focusing more on the presentation of the candidates and their platforms, and then a third phase that shows more clearly the polarization between the candidates and their strategies for obtaining victory (Muñiz et al., 2018). Thus, all the news published or broadcast during each four-day period from March 30th to May 31st, 2018, corresponding to the first phases of the campaign (Freidenberg & González Tule, 2009), and during every period of two days (not counting weekends) between June 1st and June 28th, 2018, corresponding to the third phase of the campaign (Muñiz et al., 2018), were selected.

The search process resulted in the detection of 1 762 informati-ve news stories or units of analysis. In the case of the press, 1 113 (63.17%) news stories published by Reforma (N = 343, 19.47%), El Universal (N = 158, 8.97%), Excélsior (N = 210, 11.92%), Milenio (N = 182, 10.33%) and La Jornada (N = 220, 12.49%) were analyzed. As for television, 649 of them (36.83%) aired in the morning news (N = 365) and evening news broadcasts (N = 284) of Televisa (N = 227, 12.88%), TV Azteca (N = 181, 10.27%) and Imagen TV (N = 241, 13.68%). It was decided to work with these media due to the fact that, although the new media, or social media, have been gradually gaining a space for providing campaign information for a good share of the citizenry, the press and above all, television, continue to be used in Mexico as important media for following the development of election campaigns, as well as to establish the political agenda of the competitors (Martínez Garza & Maltos, 2019; Muñiz et al., 2018).

In the case of the 2021 election campaign, the two-block selection criteria for the 2018 campaign were not applied, because this electoral process only lasted two months. Thus, all the news published or broadcast in the same newspapers and TV stations as those chosen for the previous analysis were selected for every two-day period between April 5th and June 2nd, 2021. The search process resulted in the detection of 926 news items or units of analysis. In the case of the press, 573 news items (61.88%) published in the newspapers Reforma (N = 163, 17.60%), El Universal (N = 103, 11.12%), Excélsior (N = 133, 14.36%), Milenio (N = 56, 6.05%) and La Jornada (N = 118, 12.74%) were analyzed. As for television, 353 news items (38.12%) broadcast in the morning (N = 235) and afternoon or evening (N = 118) news programs of Televisa (N = 135, 14.58%), TV Azteca (N = 90, 9.72%) and Imagen TV (N = 128, 13.82%) at the national level were analyzed.

Codebook

The codebook was made up of two large variables that were evaluated in the news: the conflict frame and the debate and political agreement frame. To this end, the methodological proposals of authors such as Dimitrova and Strömbäck (2012), Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) or Muñiz et al. (2018), regarding the operationalization and measurement of the two news frames were followed.

Conflict frame. The use of the conflict frame in the press and television news stories, which underscores the presence of information on controversial positions and even confrontation between actors in the news items, was evaluated on the basis of the proposal made by Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) in its translated Spanish version. In particular, the scale that measures the use of this frame is made up of three items, which imply determining whether the news story alluded or referred (1), or did not (0), to “Certain disagreements between the political parties, individuals, groups, institutions or countries”, to “Two sides or more than two sides of the issue or problem approached” or to the fact that “A political party, individual, group, institution or country reproaches another political party, individual, group, institution or country” with something.

Debate and political agreement frame. In turn, use in the news of the debate and political frame, which denotes the presence of information revealing the existence of discussions about proposals that result in political agreements, was evaluated (Muñiz et al., 2018). In order to measure this frame, a scale made up of four items was used to evaluate whether the story mentioned or referred to (1), or did not refer to (0), the following aspects: “Debate between political actors on a specific topic or issue”, “Political decision-making as an agreement between the actors”, “The agreement achieved by the actors after negotiations on the decision reported” and “The decision-making as listening to one another, as mutual understanding, etc.”.

Coding and reliability of the study

Several collaborators from the Political Communication Laboratory (LACOP) of the Political Sciences and International Relations Faculty at the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León participated in the codification of the units of analysis. In total, two groups were formed to analyze the press and television news stories separately. As a preliminary step, they were all trained in the use of the codebook created, and several training tests were conducted as well as a pilot test with campaign news collected randomly. Once the coding work was finished, a new analysis was carried out with a sample of 160 news items to calculate the intercoder reliability, resulting in an average value of .78 according to Krippendorff’s Alpha. In the case of the 2021 campaign, 117 news items were again analyzed to calculate the intercoder reliability, resulting in an average value of .73 according to Krippendorff’s Alpha.

Analysis of the results

Taking into consideration the first research question of the study, we started by proceeding to validate the two scales, on the basis of an examination of the data obtained in the content analysis applied to the 2018 election campaign. To this end, a factor analysis of the main components, with varimax orthogonal rotation, was carried out so as to determine to what extent the seven items on the two scales of the study organized themselves into different factors that would represent the news frames (see Table 1). In line with the findings of Muñiz et al. (2018), the analysis revealed a total of two factors or dimensions that between them explained 54.76% of the variance, KMO = .68, χ2(21, N = 1762) = 2 016.253, p < .001.

Table 1 Results of the factor analysis of the constitutive items of the news frames in the coverage of election campaigns

| Constituent items of the frames | Election campaigns | |||

| 2018 | 2021 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Factor 1: Conflict frame | ||||

| 1. The news story alludes to a particular disagreement between political parties, individuals, groups, institutions or countries. | .83 | .05 | .87 | .03 |

| 2. The news story reports that a political party, individual, group, institution or country has reproached another political party, individual, group, institution or country with something. | .75 | -.07 | .76 | -.10 |

| 3. The news story alludes to two sides, or to more than two sides, of the issue or problem addressed. | .63 | .18 | .77 | .13 |

| Factor 2: Debate and political agreement frame | ||||

| 4. The news story mentions discussion between political actors about a specific topic or issue. | .39 | .51 | .64 | .35 |

| 5. The news story presents political decision-making as an agreement between the actors. | .13 | .78 | .23 | .85 |

| 6. The news story mentions an agreement achieved by the actors after negotiations for the decision reported. | .05 | .76 | .10 | .87 |

| 7. The news story mentions the decision-making as listening to one another, as mutual understanding, etc. | -.09 | .72 | -.05 | .42 |

Note. N 2018 = 1 762; N 2021 = 926. The extraction model of the main components with orthogonal rotation (varimax). Factor loadings above .30 are in bold type.

Source: The author.

These results confirmed the validity of the construct, since it was possible to determine the presence of two dimensions that reflected the two frames that had been set out at the theoretical level. At any rate, it underscored the behavior of the item indicating that “The news story mentions discussion between political actors about a specific topic or issue”, which presented an acceptable factor value in the two dimensions found (see Table 1). This result indicates that it is an item susceptible of making up any of the two news frames, even though one of them presents a slightly greater charge than the other. To determine which of the two constructs presented a better adjustment, the internal consistency of each frame was calculated excluding the item, which made it possible to determine that its exclusion from the scale relating to the debate and political agreement frame entailed a greater impact.

To confirm this structure of two frames, a similar analysis was performed with the data obtained during the 2021 electoral campaign to answer the first research question. Thus, a factor analysis of the main components, with varimax orthogonal rotation, was carried out, which again revealed two factors or dimensions that taken together explained 60.10% of the variance, KMO = .70, χ2(21, N = 926) = 1 799.475, p < .001. These findings reaffirmed the construct validity that was detected in the 2018 data, with similar behavior in both campaigns. In this sense, again the item “The news story mentions discussion between political actors about a specific topic or issue” scored in both frames, thus confirming that it is an item susceptible to being part of either news frame (see Table 1).

Finally, the reliability or internal consistency of both constructs or frames was calculated, that is, to what extent did all the items considered for creating the scales actually contribute to the conformation of the constructs analyzed. In the case of the conflict frame, its reliability was acceptable, both for print (α2018 = .60; α2021 = .73) and television (α2018 = .66 α2021 = .80) in both the election campaigns studied. On the other hand, the scale of the debate and political agreement frame presented an acceptable internal consistency both for television (α2018 = .76; α2021 = .62), and for the press (α2018 = .61; α2021 = .65). These values are similar to those obtained in other previous studies that have used these scales to measure news frames (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Muñiz et al., 2018; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000).

In the subsequent analysis the degree to which the two frames were present within the news stories was determined, seeking to answer the second research question. In the case of the 2018 election, it was possible to detect a clear difference at the statistical level in respect of the use made of each frame, t(1761) = 20.819, p < .001, d = 0.61, 95% IC [0.16, 0.19] (see Table 2). A comparative analysis revealed a medium difference between both frames, on the basis of the value of the effect size detected (Cohen, 1988). At any rate, the dominant approach in the news items analyzed was the conflict frame (M = .28, SD = .33), as opposed to use of the debate and political agreement frame to present information (M = .11, SD = .22). In addition, although there was a tendency to an association between both frames, it was weak, r(1760) = .227, p < .001. This indicates that, in general, although there were some news stories where both frames were emphasized jointly, the tendency was for each to be dominant in a certain type of news.

Table 2 Degree of presence of each news frame in the different election campaigns

| Conflict | Debate and political agreement |

t | p | Cohen's d |

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| 2018 election campaign | .28 | .33 | .11 | .22 | 20.819 | < .001 | 0.61 |

| 2021 election campaign | .45 | .40 | .18 | .26 | 20.511 | < .001 | 0.80 |

Note. N total = 2 688; N 2018 = 1 762; N 2021 = 926

Source: The author.

On the other hand, in the case of the 2021 campaign, a similar difference was detected at the statistical level regarding the use of each news frame, t(925) = 20.511, p < .001, d = 0.80, 95% CI [0.24, 0.29] (see Table 2). Comparative analysis revealed a large difference between the two frames (Cohen, 1988), with the conflict frame once again the dominant treatment in this campaign for the news stories analyzed (M = .45, SD = .40), versus use of the debate and political agreement frame to elaborate the information (M = .18, SD = .26). Moreover, although the association between both frames was somewhat higher than in 2018, r(924) = .352, p < .001, again the same interpretation could be made about the differentiated use of both frames in most of the news stories.

Once the validity of the scales and the prevalence of the frames within the analyzed content had been reviewed, the third, fourth and fifth research questions were answered for each frame. As the study had two independent variables (media and election campaign) that could predict the behavior of both frames within the news stories, the factorial analysis of variance (UNIANOVA) was used as a statistical test to answer the research questions. Through this test it is possible to observe both the main effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable, and the possible interaction effect, that is, the effect produced when an independent variable (election campaign) moderates the influence of the other independent variable (media) used on the observed dependent variable (news frame).

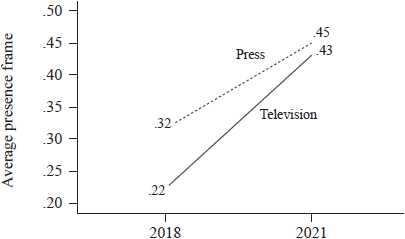

Regarding the use of conflict framing (see Table 3), the factorial analysis of variance (UNIANOVA) carried out allowed observation of the existence of statistically significant differences between the two media, F(1, 2684) = 14.291, p < .001, ηpartial 2 = .005. In this sense, press news tended to use conflict framing to a greater extent (M = .36, SD = .37) than television news (M = .30, SD = .37). Likewise, a statistically significant main effect of the election campaign was detected, F(1, 2684) = 132.056, p < .001, ηpartial 2 = .047. Thus, it was observed that in the 2018 election campaign, the conflict fame tended to be present to a lesser extent (M = .28, SD = .34) than in the 2021 campaign (M = .45, SD = .40), where the presence of this frame increased markedly.

Table 3 Degree of presence of conflict frame in media and election campaigns

| M | SD | F | df | p | ηparcial2 | |

| Media | 14.291 | (1, 2 684) | < .001 | .005 | ||

| Press | .36 | .37 | ||||

| Television | .30 | .37 | ||||

| Election campaign | 132.056 | (1, 2 684) | < .001 | .047 | ||

| 2018 | .28 | .33 | ||||

| 2021 | .45 | .40 | ||||

| Media x Campaign | 6.586 | (1, 2 684) | .010 | .002 | ||

| Press and 2018 | .32 | .34 | ||||

| Television and 2018 | .22 | .31 | ||||

| Press and 2021 | .45 | .40 | ||||

| Television and 2021 | .43 | .42 |

Note. N press = 1 686; N television = 1 002; N 2018 = 1 762; N 2021 = 926

Source: The author.

Finally, a statistically significant interaction effect was also detected between both independent variables (media x campaign) on the use of conflict framing, F(1, 2684) = 6.586, p = .010, ηpartial 2 = .002 (see Table 3). This result shows that, beyond the differences detected between media and campaigns described above, the differentiated use that was detected of conflict framing between press and television was altered by changing from one election campaign to another (see Figure 1). To determine how this moderation manifested itself, a comparison was made using the Bonferroni model. The findings allowed to determine that, while in the 2021 election campaign there were no differences between the two media, in the 2018 campaign differences were detected at the statistical level, with a greater presence of the conflict frame in the press (M = .32, SD = .34) than in television (M = .22, SD = .31).

With regard to the presence of the debate and political agreement frame in the news stories (see Table 4), the factorial analysis of variance (UNIANOVA) that was carried out allowed us to determine the existence of statistically significant differences between the two media, of F(1, 2684) = 27.720, p < .001, ηpartial 2 = .010. In this sense, press news tended to use conflict framing to a greater extent (M = .15, SD = .25) than television news (M = .09, SD = .21). Similarly, statistically significant differences between the two electoral campaigns were detected, with F(1, 2684) = 70.296, p < .001, ηpartial 2 = .026. Thus, it was observed that in the 2018 election campaign the conflict frame tended to be present to a lesser extent (M = .11, SD = .22) than in the 2021 campaign (M = .18, SD = .26), where the presence of this frame increased significantly.

Table 4 Degree of presence of debate and political agreement frame in media and election campaigns

| M | SD | F | df | p | ηparcial2 | |

| Media | 27.720 | (1, 2 684) | < .001 | .010 | ||

| Press | .15 | .25 | ||||

| Television | .09 | .21 | ||||

| Election campaign | 70.296 | (1, 2 684) | < .001 | .026 | ||

| 2018 | .11 | .22 | ||||

| 2021 | .18 | .26 | ||||

| Media x Campaign | 16.054 | (1, 2 684) | < .001 | .006 | ||

| Press and 2018 | .14 | .23 | ||||

| Television and 2018 | .05 | .17 | ||||

| Press and 2021 | .18 | .27 | ||||

| Television and 2021 | .17 | .25 |

Note. N press = 1 686; N television = 1 002; N 2018 = 1 762; N 2021 = 926

Source: The author.

And finally, the interaction effect between the two independent variables (media x campaign) on the use of the debate and political agreement frame was analyzed, and was found to be statistically significant, F(1, 2684) = 16.054, p < .001, ηpartial 2 = .006 (see Table 4). This result reflects that, together with the particular differences detected between media and between campaigns described above, the differentiated use of the debate and political agreement frame detected in the press and television was altered with the change from one electoral campaign to the other (see Figure 2). To determine how this moderation occurred, a comparison was made using the Bonferroni model. The findings allowed us to determine that while in the 2021 election campaign there were no differences between the two media, in the 2018 campaign, differences were detected at the statistical level, with a greater presence of the frame of debate and political agreement in the press (M = .14, SD = .23) than on television (M = .05, SD = .17).

Discussion and conclusions

The aim set out by this paper was to study the journalistic use made of conflict to cover the 2018 presidential election campaign and the 2021 federal Chamber of Deputies election in Mexico by the press and television nationwide. More specifically, it undertook to evaluate the use of the conflict frame linked to attacks on and reproaches against politicians, as opposed to the use of the debate or political agreement frame, which tends to present politics as an exchange of opinions seeking consensus: in an attempt to determine whether they constitute two separate frames or are connected in some way within the practice of journalism focused on covering electoral processes. To fulfill this objective, the paper set out to contrast, or to answer, the research questions.

Regarding the first research question, which asked whether conflict and debate and political agreement are two different frames or whether there are connecting points between them, the results provide a dual answer, and this finding is consistent across the two campaigns studied. On the one hand, the statistical analysis conducted leads us to assume that there is a clear difference between the two frames. But at the same time, it should be pointed out that at least one of the items used, revealed a connection between them, in particular the item relating to discussions in the political field between actors on a specific topic or issue. This is an item that measures the presence in the story of calls to debate the issue by the several actors who, according to Mazzoleni (2010), can make up the political system, usually reflecting events such as an electoral debate or a meeting between different actors that leads to a collation of ideas or proposals within the story. It can be observed, therefore, that political debate is an intermediate point connecting conflict, understood as attack and confrontation, with conflict visualized as an element of substantivity or consensus, used to provide information about the political discussion undertaken to try to reach an agreement between the positions.

But, despite an optimistic expectation that media coverage of the campaign conveys this type of low-level conflict which, as explained in the literature, would contribute to the citizens’ commitment to politics (Walgrave et al., 2018), the findings of the study reveal that its use is rather small in news about elections in the media, especially on television. Thus, in response to the second research question posed, the results obtained enable us to conclude, that to a large extent the media in Mexico tend to emphasize conflict in their coverage of election campaigns, to the detriment of the approach that underscores politics as an exercise of debate and agreement. A finding that, moreover, is consistent for both electoral campaigns. This result is in line with previous studies that show the important use that is normally made of the conflict frame to cover electoral processes (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Lengauer et al., 2012; Muñiz et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2013; Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2006).

The above reveals how attack and confrontation continue to be highly attractive elements for the Mexican media and journalists when it comes to providing a specific informative treatment of news on political election campaigns, even when the news story presents a debate between different actors belonging to the political system. Maybe the reason for this lies in their seeking to get more interest from the audience, thus perpetuating the model of spectacularization and infotainment that has prevailed in the political coverage of the elections in Mexico (Lozano et al., 2012). Something that may be manifested to a greater extent in private media, for which the use of a conflict approach can be an essential tool for capitalizing the income obtained from advertising. The fact that the study was conducted only with private media limits discussion of the use of these frames in search of an informative interest; therefore, it would be convenient for future studies to expand the sample to include informative contents from public media, attending to their particular incidence in the population (Martínez Garza & Maltos, 2019).

On the other hand, referring now to the comparative analysis of the use made of the two frames by the different media analyzed, the findings of the study allow us to answer the third research question posed. Although the differences were small (Cohen, 1988), the findings of the study allow us to conclude that the conflict approach tends to be used slightly more frequently by the press than by television in the federal electoral processes, a result in line with what has already been observed by other authors and, for the Mexican case, in the previous study by Muñiz et al. (2018) although in this particular case the study was conducted on the 2015 state election campaign in Nuevo León. Perhaps this result can be explained by the fact that the press seeks to provide a more objective coverage, one that provides opposing points of view on social reality, even if this entails covering the accusations and reproaches cast by the different actors. At any rate, the findings of the present study contribute to knowledge of the differentiated framing of conflict made by the media, although it will be necessary to continue deepening the research in order to determine if it is a pattern that will be repeated in future elections.

This conclusion is supported by results relating to the use of the debate and political agreement frame. With regard to the third research question, a difference in the use of this approach was observed for both election campaigns between the two media, with the press once again being the medium that made the greatest use of this informative treatment, although the difference with television was small considering the size of the effect. Therefore, it is confirmed that newspapers tend to emphasize the different positions adopted within the debate, maybe seeking to do away with the possibility of journalistic bias, although it may also be due to the informative dynamics of each newspaper or even to the larger space that is usually available to narrate the information. Still, this finding should be revised by undertaking a thorough analysis of the informative framing by different newspapers and TV stations in order to determine whether this is actually a common pattern in journalistic practice.

In addition, the fourth research question asked whether there were differences in the use of the two frames in the two election campaigns. The findings of the study allow to conclude that both frames tended to increase significantly in the 2021 campaign, compared to the 2018 presidential campaign; an increase that was especially evident in the case of use of the conflict frame. In this regard, it is interesting to note how in the 2021 election, when the composition of the Chamber of Deputies was at stake ‒an election where the informative focus is usually diluted by there being so many candidates‒, there was actually a greater prevalence of conflict framing than in the 2018 campaign, where the presidency of the republic was at stake and, therefore, there was a greater personalization and focus of the coverage on just a few candidates, where it would be natural for the conflict frame to be more widely present. This result reveals how a mid-term campaign can provoke a lot of confrontation, perhaps taking into consideration that its results can be interpreted as a thermometer reading for the level of citizen support that the presidential administration has at the time.

Finally, the paper sought to answer the fifth research question, which raised the doubt as to whether the year of the election campaign studied had some moderating effect on the use of the two frames by the media. In this regard, a similar pattern was detected in both frames, as their use by the media did not differ in the 2021 campaign, while in the 2018 campaign it was always the press that made more extensive use of both frames. This again highlights how the 2021 federal campaign elicited press coverage with a greater emphasis on political debate and confrontation, regardless of the media analyzed. Furthermore, it is concluded that, independently of which of the electoral campaigns is studied, the innate news value of conflict remains fixed in the journalistic routine when it comes to reporting on politics, which in any case is emphasized in a campaign where the political management of the incumbent government is subjected to public scrutiny.

Independently of the findings described above, it is important to remember that these findings should be contrasted with those of other studies that will be able to evaluate the informational framing carried out in future federal election campaigns in Mexico. Especially because, although it seems that they are in line with the usual media use of conflict framing to cover election campaigns and politics that has been detected at the international level, the study of framing should not be carried out without paying attention to the cultural context where the information is presented, in line with what has recently been suggested by Rodelo (2020). Furthermore, beyond analysis of the coverage of elections, where political confrontation tends to increase, it would be important to evaluate also the use of both news frames in the media coverage of daily governmental and legislative administration, where it is possible that the debate and political agreement frame will emerge in greater profusion in the news content. With respect to this issue, there are gaps in the research conducted in the Mexican context, which makes it possible to visualize it as an attractive line of work.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the collaborators of the research team for their support in the coding of news stories, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Funding

This research was financed by the project of the National Council of Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología -CONACYT) titled “Analysis of media coverage of election campaigns and its impact on political disaffection and democratic citizen engagement” (grant number 280739).

REFERENCES

Bartholomé, G., Lecheler, S. & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Towards a typology of conflict frames. Substantiveness and interventionism in political conflict news. Journalism Studies, 19(12), 1689-1711. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1299033 [ Links ]

Bjarnøe, C., de Vreese, C. H. & Albæk, E. (2020). The effect of being conflict non-avoidant: linking conflict framing and political participation. West European Politics, 43(1), 102-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1572334 [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Colvin, R. M., Bradd Witt, G., Lacey, J. & McCrea, R. (2020). The role of conflict framing and social identity in public opinion about land use change: An experimental test in the Australian context. Environmental Policy and Governance, 30(2), 84-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1879 [ Links ]

de Vreese, C. H. (2012). New avenues for framing research. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 365-375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211426331 [ Links ]

de Vreese, C. H. (2014). Mediatization of news: The role of journalistic framing. En J. Strömbäck & F. Esser (Eds.), Mediatization of politics. Understanding the transformation of western democracies (pp. 137-155). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137275844_8 [ Links ]

Dimitrova, D. V. & Strömbäck, J. (2012). Election news in Sweden and the United States: A comparative study of sources and media frames. Journalism, 13(5), 604-619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911431546 [ Links ]

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x [ Links ]

Ergün, E. & Karsten, N. (2019). Media logic in the coverage of election promises: comparative evidence from the Netherlands and the US. Acta Politica, 56, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-019-00141-8 [ Links ]

Freidenberg, F. & González Tule, L. (2009). Estrategias partidistas, preferencias ciudadanas y anuncios televisivos: Un análisis de la campaña electoral mexicana de 2006. Política y Gobierno, 16(2), 269-320. http://www.politicaygobierno.cide.edu/index.php/pyg/article/view/205 [ Links ]

Galais, C. (2018). Conflict frames and emotional reactions: a story about the Spanish Indignados. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30(4), 446-465. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1550416 [ Links ]

Gerth, M. A. & Siegert, G. (2012). Patterns of consistence and constriction: How news media frame the coverage of direct democratic campaigns. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 279-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211426326 [ Links ]

Gronemeyer, M., del Pino, M. & Porath, W. (2019). The use of generic frames in elite press: Between conflict, neutrality, and an empowered journalist. Journalism Practice, 14(8), 954-970. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1665473 [ Links ]

Lengauer, G., Esser, F. & Berganza, R. (2012). Negativity in political news: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 179-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427800 [ Links ]

Lozano, J. C., Cantú, J., Martínez, F. J. & Smith, C. (2012). Evaluación del desempeño de los medios informativos en las elecciones de 2009 en Monterrey. Comunicación y Sociedad, (18), 173-197. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i18.195 [ Links ]

Matthes, J. (2012). Framing politics: An integrative approach. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 247-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211426324 [ Links ]

Martínez Garza, F. J. & Maltos, A. L. (2019). La elección federal en telediarios públicos. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública, 14(27), 79-93. https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484911e.2019.27.68549 [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Saldierna, A. & Marañón, F. (2018). Framing of electoral processes: The stages of the campaign as a moderator of the presence of political frames in the news. Palabra Clave, 21(3), 740-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2018.21.3.5 [ Links ]

Rodelo, F. V. (2020). Factores antecedentes de los encuadres de juego estratégico y temático en la cobertura de campañas electorales locales en el contexto mexicano. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7643. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7643 [ Links ]

Schuck, A. R. T. (2017). Media malaise and political cynicism. En P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1-19). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0066 [ Links ]

Schuck, A. R. T., Vliegenthart, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Elenbaas, M., Azrout, R., van Spanje, J. & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Explaining campaign news coverage: How medium, time, and context explain variation in the media framing of the 2009 European parliamentary elections. Journal of Political Marketing, 12(1), 8-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2013.752192 [ Links ]

Schuck, A. R. T., Vliegenthart, R. & de Vreese, C. H. (2016). Who’s afraid of conflict? The mobilizing effect of conflict framing in campaign news. British Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000525 [ Links ]

Semetko, H. A. & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: a content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x [ Links ]

Sevenans, J. & Vliegenthart, R. (2016). Political agenda-setting in Belgium and the Netherlands. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(1), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015607336 [ Links ]

Strömbäck, J. & Dimitrova, D. V. (2006). Political and media systems matter: A comparison of election news coverage in Sweden and the United States. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 11(4), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X06293549 [ Links ]

Trussler, M. & Soroka, S. (2014). Consumer demand for cynical and negative news frames. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 360-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214524832 [ Links ]

Walgrave, S., Sevenans, J., Van Camp, K. & Loewen, P. (2018). What draws politicians’ attention? An experimental study of issue framing and its effect on individual political elites. Political Behavior, 40, 547-569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9413-9 [ Links ]

How to cite:

Muñiz, C. (2022). When attack meets debate. Presence of conflict in the framing of the 2018 and 2021 Mexican federal elections. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7841. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.7841

Received: June 03, 2020; Accepted: November 22, 2021; Published: January 12, 2022

text in

text in