Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub Mar 31, 2023

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.7735

Articles

General theme

The Communication Structure of the Government of Puerto Rico; Evolution and Challenges

1 Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España. rosasesenton@gmail.com

The communication structure of a government is an area barely studied. This article intends to present academic perspectives to shape a structural organizational model of communication that is used as a reference in the evolutionary analysis of the communication of the Puerto Rico central government. It is concluded that the communication structure of the Government of Puerto Rico has presented significant structural modifications during six administrations that contain efficiencies, deficiencies and challenges for the management of its public communication.

Keywords: Structure; communication; Government; Puerto Rico; evolution; challenges

La estructura de comunicación de un gobierno es un área poco estudiada. Este artículo tiene el objetivo de presentar perspectivas académicas para conformar un modelo estructural comunicacional fundamental que se utiliza como un referente en el análisis evolutivo de la estructura de comunicación del Gobierno Central (poder ejecutivo) de Puerto Rico. Se concluye que la estructura de comunicación del Gobierno de Puerto Rico ha presentado modificaciones estructurales significativas en seis periodos de gobernación que contienen eficiencias, deficiencias y retos para la gestión de su comunicación pública.

Palabras clave: Estructura; comunicación; Gobierno; Puerto Rico; evolución; retos

A estrutura de comunicação de um governo é uma área pouco estudada. Este artigo tem o objetivo de apresentar perspectivas acadêmicas para formar um modelo estrutural de comunicação fundamental que seja usado como referência na análise evolutiva da estrutura de comunicação do Governo Central (poder executivo) de Porto Rico. Conclui-se que a estrutura de comunicação do Governo de Porto Rico apresentou modificações significativas em seis períodos de governo que contêm eficiências, deficiências e desafios para a gestão de sua comunicação pública.

Palavras chave: Estrutura; comunicación; Governo; Porto Rico; evolução; desafios

Introduction

An adequate organizational structure considers the unification of fundamental communication units: Chief of Staff, Press Unit, Relations with Special Interest Groups, Crisis Management, Public Policy, Spokesperson, Internal Communication Flow, Centralized Perspective, and a Strategic Communications Unit with the following divisions: 1) Monitoring; and 2) Image, Discourse and Digital Communication Production (Canel, 1999; Deutsch,1969; Elizalde, 2006; Kumar, 2007; Sullivan, 2001).

These perspectives, that share practical and academic territories, appear unified in this article with the aim of building a Structural Organizational Model fundamental for government communication efforts. Through these perspectives, I establish a framework to analyze the communication structure of the Government of Puerto Rico. A thorough review of academic literature revealed that no studies address the analysis of the communication structure of the central government of Puerto Rico.2 Therefore, the goal of this text is to present an evolutionary analysis of the communication structure of the central government of Puerto Rico. It also reflects the challenges tied to the structural modifications identified in the following periods: 1972-1976, 1984-1988, 1992-2000, 2000-2004, 2012-2016 and 2016-2019.

Methodology

Our investigation presents an open, reflexive and critical analysis of the evolution of the structure of the executive branch of the government of Puerto Rico. Interviews are the main data collection technique and they were used to obtain first hand knowledge of this structure. We interviewed the following governors: Rafael Hernández Colón, Pedro Rosselló González, Sila M. Calderón, Aníbal Acevedo Vilá and Alejandro García Padilla, as well as key government officials that were part of the communications structure: Communication Heads, News Directors, Secretaries of Public Affairs, and Secretaries of State who were part of the communication structure during said periods and, because of the nature of their work, had first hand knowledge of this structure, including its creation, modifications and communication strategies employed. We also looked into narrations from journalists, senators and ex-government officials who contributed to the analysis of the communication structure of the executive branch of the government of Puerto Rico. These narrations are part of an unexplored history and initiated the process of critical analysis in this investigation.

We also used other non standard techniques that are part of qualitative research, such as the revision of the Constitution of Puerto Rico, executive orders, laws, communication plans of specific administrations, news articles, economic reports by the Office of Management and Budget, budget documents of the Comptroller’s Office of Puerto Rico and other documentation related to communication during those periods such as: memos, letters, and meeting minutes. These research sources complemented the interviews and provided documentary richness to the analysis.

In this work there is an emphasis on “structure” as the analysis category posited by Sanders and Canel (2013) in Government communication in 15 countries: Themes and challenges, where the authors stressed the indispensable nature of structure in government communication efforts. Keeping in mind the essential role of structure, I have not limited the study to identifying the structural composition of the Government of Puerto Rico in each period, but I have also compared it to a Structural Organizational Model proposed in this text with the purpose of pinpointing efficiencies, deficiencies and challenges (Sanders & Canel, 2013, pp. 1-5).

The structural organization of government communication

From an academic perspective, the structure of government communication is viewed as the way in which the government organizes its communication efforts. In other words, it refers to the internal aspects of external communication and to a management tool for the dissemination of information on public policy (Elizalde, 2006; Sanders & Canel; 2010).

The organizational structure has considerable repercussions on a government’s public communication efforts since what is ultimately shared with the public is created in this space. This is why deciding which communication units will be included in this structure and how they are organized is a challenge for those who plan government communication.

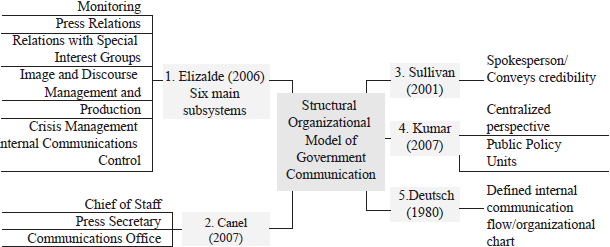

In this section I present five academic perspectives that address the organizational structure of government communication (Canel, 1999; Deutsch, 1969; Elizalde, 2006; Kumar, 2007; Sullivan, 2001). These authors belong to a group of researchers who think communication is an intrinsic and vital part of both politics and government. These perspectives suggest a structural organizational model that I rely on for the analysis of the communication structure of the Central Government of Puerto Rico.

Description of the Suggested Structural Organizational Model

The government’s structural organizational model for communication is composed of five parts that represent academic perspectives about fundamental units in a communication structure. In the first one I present six relevant communication units according to Elizalde (2006); the second one has three fundamental units that belong in a government’s communication structure (Canel, 2007); the third part includes the spokesperson unit (Sullivan, 2001); the fourth presents a centralized perspective and public policy units (Kumar, 2007) and, finally, the relevance of internal communication channels is addressed (Deutsch, 1980).

Six Systems in the Communication Structure

According to Elizalde (2006), the structure of communication is about “management structure”, therefore, his view of organizational structure stems from a cohesive systemic integration that guides government public communication efforts. The author believes that the structural basis of government communication should have the following systems: Monitoring, Press Relations, Relations with Special Interest Groups, Image and Discourse Management and Production, Crisis Management and an internal communication system (Elizalde, 2006, p. 196).

The first unit, Monitoring, contributes with input, that is, the selection of facts, events, incidents, tendencies and topics that are relevant for the planning of government communication efforts. This includes public opinion analysis and press clippings.

The aim of the second unit, Press Relations, is to establish a link between the government and members of the press and media. Elizalde (2006) mentions that the challenge of this unit is finding an effective way to systematize this link, which is essential for the government. Democratic systems face challenges in creating this link because of the right to free speech and public auditing of the information the government puts forward. Protection of free speech promotes public scrutiny of government information, which is why the authors suggest a proactive stance from the government in identifying and classifying news outlets in order to detect those that are not serious about their profession (p. 196).

In the third unit, Relations with Special Interest Groups, links are created with groups and entities that have vested interests in government affairs. Relations with these groups focus on establishing a consensus as a strategic action in shaping government communications. This is especially true in modern times where digital communication is fragmented, exponential and instant (Riorda, 2006, p. 20).

The fourth unit, Image and Discourse Management and Production, is geared toward building the image of the governor through strategic planning of both public appearances and discourse (p. 98). The fifth unit, Crisis (or Serious Problem) Management, entails the effective organization of government responses or actions in crisis situations. According to Elizalde, these can range from pressure and liability claims against the government, to social sanctions (p. 198). Finally, the sixth system, Internal Communications Control, establishes internal information channels and systems in the structure that typically appear in an organizational chart (p. 198).

Three Key Systems in the Communication Structure

The suggested model of organizational structure incorporates the perspective of Canel (2007). His multiple analyses of the structural models of presidential communication in the United States and the United Kingdom support the relevance of the units suggested by Elizalde (2006). However, he states that there are three systems that must be emphasized since they comprise the primary units of the communication infrastructure: Chief of Staff, Press Secretary and Communications Office. These units, as Kumar (2007) explains, are typically filled by trusted officials who are mainly responsible for communication management and, therefore, the functionality of the structure (Canel, 2007, p. 166; Kumar, 2007, p. 6).

Canel’s description of the responsibilities of these officials stems from his research on the historic evolution of White House infrastructure (United States). For example, the Chief of Staff is the right hand of the leader and must supervise the functioning of the cabinet and coordinate strategic decisions about public policy, in addition to communication decisions (Canel, 2007, pp. 166-167). On the other hand, the Press Secretary disseminates information related to public administration and is in charge of communication between the government and the press/media on a daily basis (p. 172).

Finally, the Communications Office develops the communication strategy of the president, among other functions. This task, which directly involves the president, implies coordination with the public policy plan through the Chief of Staff (Canel, 2007, pp. 166-172). The Communications Office includes units dedicated to managing the government’s digital communication, which mainly includes websites and social media.

Spokesperson: Relevance of an Individual Who Conveys Credibility

The perspective of Sullivan (2001) is also considered in the proposed model for organizing government communication. His practical experience within the federal government considers the credibility factor in the analysis of the structural organization of government communication. The author states that the structure will require an individual who conveys credibility. This perspective underscores the need for a spokesperson that citizens perceive as credible and trustworthy. She argues that people not only need truthful and objective information but also someone who delivers this information with credibility, so they can make informed decisions and reach independent conclusions (Sullivan, 2001, p. 3).

Centralized Perspective within the Structure and Units of Public Policy

The fourth perspective incorporates Kumar (2007), who researched the communications model of the White House in Washington in The White House Transition Project (1997-2017). She posits that the communication structure will require a centralized perspective as well as units dedicated to public policy and communicating it. Kumar (2007) explains that communication that is centralized around the authority figure yields a more effective operation (pp. 5-7).

Kumar (2007) also states that the structure of government communication requires units dedicated to the communication of public policy. These units plan constant public communication focused on the substance of each project and ignore other issues of public discussion that may interfere with the main axis of public policy (pp. 5-7).

Internal Communication Channels in the Structure

The suggested model for organizing government communication considers the theoretical framework of Deutsch (1980) on the flow of information in the communication structure. The author has stated that the structure of communication will require defined channels that determine internal information flow (p. 24). The systematic vision that Deutsch provides may find its roots in the theory of systems that ties the relationship between the parts of a structure to their functionality (Bertalanffy, 1989). Similarly, in government communication the efficient flow between internal channels places the structure in a position of greater strength when dealing with external information that may continually impact the system and also helps plan communication that anticipates the needs of citizens (Deutsch, 1980, p. 24). All of the perspectives discussed interact cohesively as pieces of a puzzle to articulate the suggested organizational structure.

Results

The Communication Structure of the Government of Puerto Rico

The structure of communication of the Central Government of Puerto Rico is grounded on a democratic political system regulated by laws that protect freedom of speech, freedom of the press, transparency and monitor partisanship in government communication. Despite thorough regulations directed at achieving transparency, government communication has been characterized by citizens’ lack of trust. They question if what the government communicates is truly transparent. Transparency laws have not been able to redeem a government with damaged credibility. It is not clear if we can make a direct link between the credibility crisis that the government is going through and its communication structure; however, it is likely that the problem has roots in a structural element. What follows is an evolutionary analysis of the structure of the Central Government of Puerto Rico.

Description of the communication structure of the government of puerto rico

Background

The communication structure of the Central Government (executive branch) of Puerto Rico has two main characteristics: partisan politics and the influence of the United States Government’s Communication model. In the year 1971 these aspects converged and gave way to the traditional structure of communication of the central government.

First, partisan politics in the communication structure derive from the electoral campaign of the then candidate for governor Rafael Hernández Colón. As stated by the ex-governor, his first electoral campaign was characterized by a high level of planning and structural organization. When he was elected governor he created a broader communication structure than the one that was in place, and it was led mainly by those who had collaborated actively in the electoral campaign.

In terms of the second characteristic, the structural model of communication that was established within the central government during the 1972-1976 period tried to emulate aspects of the White House model, particularly by establishing units dedicated to strategic communication, as I will explain below. Although governors of each period modified the communication structure, the structural model still resembles that of the government of the United States.

Evolution of the Communication Structure of the Government of Puerto Rico

As observed in Table 1, the communication structure of the Central Government of Puerto Rico has undergone significant structural modifications, from 1972 to 2019. What follows is a window into the structural modifications that belong to each period of governance.

Table 1 Modifications to the structure of the executive branch, government of Puerto Rico

| Governors | |||||||

| 1952-1972 | 1972-1976 | 1984-1988 | 1992-2000 | 2000-2004 | 2012-2016 | 2016-2019 | |

| Communication Units | Current Structure |

Rafael Hernández Colón |

Rafael Hernández Colón |

Pedro Rosselló González |

Sila Calderón Serra |

Alejandro García Padilla |

Ricardo Rosselló Nevares |

| Interagency Coordinator | |||||||

| Press Secretary | |||||||

| Communications Office | |||||||

| Chief of Staff | |||||||

| Central Communications Office | |||||||

| Secretary of Public

Affairs- Spokesperson |

|||||||

| Secretary of Public Affairs and Press |

|||||||

| Secretary of Public

Affairs and Public Policy |

|||||||

| Office of the Chief Information Officer | |||||||

Source: The author.

Governor: Rafael Hernández Colón, Popular Democratic Party

When Rafael Hernández Colón of the Popular Democratic Party came into power the central government had a basic communication structure that was set in place in the 1950s, and was composed mainly of the Press Secretary and an Interagency Coordinator, in charge of the constitutional cabinet.

The first structural modification was the creation of the Communications Office in 1973. This office was created to emulate the White House Communications Office (Rafael Hernández Colón, personal communication, April 19th, 2018). This step institutionalized a broader strategic planning vision of the structure of communication of the government of Puerto Rico. With a link to this office, a complimentary operation of monitoring, and image and discourse production was begun. This goes in line with the perspective of Elizalde (2006) who considered these units essential to the structure.

Two challenges associated with this structural modification relate to politicization and bureaucracy. This period seems to have institutionalized the practice of granting contracts of communications positions to people who were part of the electoral campaign. For example, the director of the electoral campaign of Hernández Colón in the year 192 became his chief communications advisor. This common practice in the country poses the risk of politicization of the structure, which has resulted in people’s lack of trust.

A second challenge is bureaucracy. The creation of the Communications Office also became a strategy to align the public discourse of agency chiefs with the governor’s main public policy message. This strategy had bureaucratic implications because the governor established parameters to filter agency chiefs’ public communication. A new process of approval is incorporated into the structure: the Communications Office would authorize these officials’ communications with the goal of unifying the government’s public message. This internal regulation prevailed in subsequent periods, sometimes limiting the information that should reach citizens.

Governor: Rafael Hernández Colón, Popular Democratic Party

During the period of 1984-1988 a second significant modification to the communications structure of the central government was introduced. No other modification had been introduced since 1973. Governor Hernández Colón issued the Executive Order of May 6th, 1986, which created the position of Chief of Staff. This role had been fulfilled up to that point by the Interagency Coordinator (Rafael Hernández Colón, personal communication, April 19th, 2018). This modification is in line with Canel (2007) who considers the Chief of Staff a fundamental unit of the communications structure (p. 166).

An analysis of the first period leads to two possible reasons why the communications structure of the central government was modified. First, elevating the office of Interagency Coordinator to a higher level: member of the cabinet. Second, improve communication between cabinet agencies and the communication structure of the central government. In this modification there is a new hierarchical authority that professionalized the structure and improved communication between the governor and constitutional cabinet agencies.

A challenge that came with this modification also has to do with politicization. The new unit led by the Chief of Staff in a way underscores the politicized nature of the structure. The office was created for Sila Calderón, who was recognized as an influential figure in the Popular Democratic Party.

Governor: Pedro Rosselló, New Progressive Party

The third modification to the central government’s communication structure took effect when the Communications Office became the new Central Communications Office (known in Spanish as OCC). Through an executive order, governor Pedro Rosselló reformulated the Communications Office by establishing, in 1993, a more complex operation: greater budgetary expenditure and one of the most efficient communication projections that had been seen up to that moment in the government of Puerto Rico (Pedro Rosselló, personal communication, November 7th, 2018.)

Governor Rosselló adopted a macro-entrepreneurial view of the Central Communications Office, that focused on a more aggressive link between government agencies and units. The strategy that reconstituted the Communications Office as the Central Communications Office considered: consolidating and managing the communications budget of constitutional cabinet agencies, and offering advising, consulting and supervision of public communication services to all government agencies. During this period there was a more strict control over agency chiefs’ public communication and over managing the communications budget.

A challenge brought about by this third structural modification had to do with politicization. The strategy of combining all public communication efforts of all government agencies under a single budget led to party propaganda within government communication, which intensified during governor Rosselló’s second term.

This practice of mixing party politics with government communication along with the corruption cases that came to light during Pedro Rosselló’s leadership contributed to the deterioration of the already lacerated credibility of government communication.

Governor: Sila Calderón, Popular Democratic Party

The fourth significant modification to the communication structure created by Hernández Colón in 1973 happened in 2002. Governor Sila M. Calderón created the Office of Public Affairs through executive order OE-2002-28. This modification did not occur on its own; it involved the official appointment of a spokesperson and the creation of a unit dedicated to the communication of Public Policy, which until now had been absent in the structure (Sila M. Calderón, personal communication, July 31st, 2019). This is how the figure that Sullivan (2001) described was institutionalized in the structure. Sullivan states that this person must project credible and reliable traits before citizens, and commit to planning the communication of government public policy.

Jorge Colberg, who was the first Secretary of Public Affairs, narrates that the problem of the absence of a designated spokesperson led to the creation of the position. Colberg explains (personal communication, August 3rd, 2018), that this modification broke the tradition of using the Press Secretary as an incidental spokesperson alongside the governor, as had happened in previous periods.

The Secretary of Public Affairs would be in charge of planning and communicating the government’s public policy projects in all their stages. This modification incorporates the unit that Kumar (2007) has considered essential to center government communication on the key aspects of projects instead of the noise of public discussion that often interferes with the main focus of public policy (p. 5).

A challenge associated with this structural modification is directly related to the politicization that had already surfaced in the structure in the first period. The person appointed to occupy the position aroused skepticism among sectors of the country for being highly identified by his collaboration with the campaigns of the Popular Democratic Party.

Governor: Alejandro García Padilla, Popular Democratic Party

The fifth modification of the central government’s communication structure consisted of merging the Press Unit and the Office of Public Affairs to form the new unit of the Office of Public Affairs Public and Press. It was the first time that a governor intervened to reformulate the Press Office structure (Alejandro García Padilla, personal communication, May 15th, 2018).

However, these units were complementary, and had an identity of their own with defined functions that, by themselves, already represent complex systems. This merger may have threatened the effectiveness of the communication structure. Both Kumar (2007) and Sullivan (2012) consider it important to determine the functions of each unit to avoid excess loads that threaten coherence in government communication (Kumar, 2007, pp. 1-6; Sullivan, 2012, p. 16).

Governor: Ricardo Rosselló, New Progressive Party

This period was a sensitive one for the communication structure of the government because Puerto Rico was going through a crisis caused by the passing of legislation S2328 on June 30th, 2016, known as Puerto Rico Oversight Management and Economic Stability Act or its acronym P.R.O.M.E.S.A (Congressional Research Service, 2016). This law, imposed by the United States Congress, established the presence of an Oversight Board to stabilize the economic situation of the government as a result of a public debt that neared 72 billion dollars. In the new scenario, the Oversight Board acted as an unexpected voice that seemed to destabilize government communication.

Given this event, which conditioned government communication, three modifications to the communication structure emerged. In the first modification, Governor Ricardo Rosselló, through an executive order, reformulated the position of Secretary of Public Affairs created during the fourth period (2000-2004) to establish the Office of Public Affairs and Public Policy. In addition to appointing a spokesperson with greater public exposure, this modification gave way to communication centered on the substantive aspect of public policy projects that Kumar (2007) considers essential to minimize deviations in communication due to noise from public opinion (p. 5).

The second modification to the structure consisted of creating a unit dedicated to technology and innovation in Puerto Rico and appointing a Chief Information Officer to streamline government information technology processes (OE-24.1.2017). These units operated in line with the Central Office of Communications and shared a planned vision of communication.

Finally, the third modification by Governor Ricardo Rosselló eliminated the Central Office of Communications. In the new arrangement, the director of communications, Rossy Santiago, went on to the office of Anthony Maceira, who had been appointed by Rosselló as Secretary of Public Affairs and Public Policy. Maceria explains that the modification was made to create a more efficient communication structure (Rosario, 2019).

According to the suggested structural organization model, it is counterproductive to disintegrate one of the units that Canel (2007) asserts is fundamental in the structure. The structure requires both a unit dedicated to the management and communication of public policy, as well as a professionalized Communications Office that is in charge of planning the communication strategy of the government in the medium and long term.

Given the atypical scenario that government communication was going through, a structural organization with the basic units discussed earlier was essential. Disintegrating the Office of Communication in the midst of the government’s worst communication crisis suggests deficiencies in structural planning that required both the strengthening of how the public policy message was transmitted as well as the general projection of the government through the Office of Communication.

One aspect that once again challenged government communication during this period was politicization. Governor Rosselló appointed two officials who led the political-partisan campaign for the positions of Secretary of Public Affairs and Public Policy and Chief of Staff: Ramón Rosario and William Villafañe, respectively. As I have pointed out from the first period, the practice of tainting the communication structure with partisan shadows became a tradition in Puerto Rico; all this before citizens who see the government with increased skepticism and mistrust.

In addition to these appointments, the issue of politicization was drastically evidenced during this period. In July, 2019, a press leak made public the content of a conversation where Governor Ricardo Rosselló and his intimate group of advisers and officials within the communication structure exchanged homophobic expressions, teasing, plans to persecute political opponents and agendas to advance their partisan causes. It was unbelievable that the history of Puerto Rican politics was offering the crudest story about politicization within the structure of the central government. The people of Puerto Rico reminded him that they forgive, but do not forget, when in a massive march they demanded and achieved the resignation of the governor. Ironically, the fall of Ricardo Rosselló came as a result of a communication problem and the inappropriate use of new technologies. However, it is also rooted in partisanship which, with varying intensities, has tainted the structure ever since the first period analyzed.

According to the suggested structural organization model, at the height of this period, there were no units dedicated to communication with interest groups, crisis management and serious situations of communication of public policy. Nor did they have an organizational chart as a tool for determining the flow of internal communication. These deficiencies, in addition to the challenges that I have previously indicated, did not support the effective management of communication of the central government during the period 2016-2019.

Conclusions

In Puerto Rico, the government manages its communication through a centralized structure headed by the governor, who is the communicative figure with the greatest media exposure. Significant modifications since 1972 have led to the current structure of the model: Chief of Staff Office, Press Office, Central Communications Office, and departments for Monitoring, Speech Production, Government Image Management, Digital Communication, Office of Public Affairs and Designated Spokesperson.

The limitations observed in the structural organization adopted by the government of Puerto Rico are related to the absence of units dedicated to building relations with interest groups and to crisis management or management of serious situations related to public policy, that Elizalde (2006) considers essential in the operation of government structure

The crisis that the government went through during the period of 2016-2019, due to the approval of the S2328 legislation, P.R.O.M.E.S.A, and the imposition of an Oversight Board that took the fiscal reins of the government and made government communication dependent, probably required a reinforcement of what Elizalde (2006) has called links to vested interest groups in government, and Riorda (2006) has cataloged as the strategic actions of the consensus (p. 20). Similarly, there was a great need for units dedicated to the communication of serious matters in the face of the atypical scenario created by the Oversight Board.

Another limitation observed is the presence of political-partisan currents, which have influenced the structure since its first modification during the period of 1972-1976. An evolutionary analysis has revealed an evident practice of hiring individuals who collaborate in party campaigns to occupy leading positions in the communication structure. This practice, of a structural nature, has certainly lacerated the credibility of the government, and this has resulted in the distrust of the people.

Finally, a contradiction arises from the evolutionary aspect of the communication structure of the central government. On the one hand, a structural organization developed in line with the units of the suggested structural organization model is observable (Canel, 1999; Deutsch, 1980; Elizalde et al., 2006; Kumar, 2007; Sullivan, 2001); on the other hand, the result has been less credibility before the public. That is, as the organization of the communication structure develops, bias decreases credibility and increases people’s distrust of the government. This reality will lead to new reflections on inefficiencies that seem to transcend structure, and point toward the character of communicators in the Government of Puerto Rico.

REFERENCES

Bertalanffy, L. (1989). Teoría General de los Sistemas. Fundamentos, Desarrollos, Aplicaciones. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Canel, M. J. (1999). Comunicación política: Una guía para su estudio y práctica (1ª ed.). Tecnos. [ Links ]

Canel, M. (2007). Comunicación de las instituciones públicas. (1ª ed.). Editorial Tecnos. [ Links ]

Congressional Research Service. (2016). The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; H.R. 5278, S. 2328). https://crsreports.congress.gov/ [ Links ]

Deutsch, K. (1963). Los nervios del gobierno: modelos de comunicación y control políticos. Paidós. [ Links ]

Deutsch, K. (1980). Política y Administración Pública (1ª ed.). Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. https://repositorio.tec.mx/handle/11285/574316 [ Links ]

Elizalde, L. (2006). La Comunicación Gubernamental; Problemas y Soluciones Estratégicas. En L. Elizalde, D. Fernández & M. Riorda (Eds.), La construcción del consenso: Gestión de la comunicación gubernamental (pp. 145-249). La Crujía. [ Links ]

Elizalde, L., Fernández, D., Riorda, M. (2006). La construcción del consenso: Gestión de la comunicación gubernamental. La Crujía. [ Links ]

Kumar, M. (2007). Managing the President’s Message: The White House Communications Operation. http://whitehousetransitionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Kumar-Managing8.pdf [ Links ]

Riorda, M. (2006). Hacia un Modelo de Comunicación Gubernamental para el Consenso. En L. Elizalde, D. Fernández & M. Riorda (Eds.), La construcción del consenso: Gestión de la comunicación gubernamental (pp. 17-131). La Crujía. [ Links ]

Rosario, F. (2019, 6 de marzo). Confirman cambios y renuncia en La Fortaleza. PrimeraHora. https://www.primerahora.com/noticias/gobierno-politica/notas/confirman-cambios-y-renuncia-en-la-fortaleza/ [ Links ]

Sanders, K. & Canel, M. (2010). Para estudiar la comunicación de los gobiernos: Un análisis del estado de la cuestión. Comunicación y Sociedad, XXIII(1), 7-48, http://dadun.unav.edu/bitstream/10171/16146/1/Para%20estudiar%20la%20comunicacion.pdf [ Links ]

Sanders, K. & Canel, M. (2013). Government communication in 15 countries: Themes and challenge. Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Sullivan, M. (2001). A Responsible Press Office. U.S. Dept of State, International Programs. https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/media/pressoffice.pdf [ Links ]

Sullivan, M. (2010). A Responsible Press Office: An Insider Guide. https://photos.state.gov/libraries/korea/49271/dwoa_122709/A_Responsible_Press_Office.pdf [ Links ]

Sullivan, M. (2012). A Responsible Press Office in the Digital Age; Handbook Series. https://static.america.gov/uploads/sites/8/2016/06/A-Responsible-Press-Office-in-the-Digital-Age_Handbook-Series_English_508.pdf [ Links ]

2This article is part of a broader investigation titled Communication of the Executive Branch in Puerto Rico (1972-2019) which addresses deficiencies in the analysis framework of the communication structure of the government of Puerto Rico.

How to cite:

The Communication Structure of the Government of Puerto Rico; Evolution and Challenges. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7735. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.7735

Received: February 16, 2020; Accepted: February 04, 2021; Published: March 02, 2022

text in

text in