Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub Mar 24, 2023

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8166

Articles

Collaborative knowledge practices and social movements

The journalistic coverage of social movements in Ibero-America

1 Universidad Privada del Norte, Perú. maria.mamani@upn.edu.pe

2 Universidad Privada del Norte, Perú. jorgeperezbaca@gmail.com

This paper analyzes the journalistic coverage of social movements in Ibero-America over the last ten years (2011-2021). A systematic review of the literature was carried out to analyze the diffusion of social activism in the press. Thus, the set of sources was analyzed, identifying, in the traditional media, coverage related to the political power and the reinforcement of stereotypes, and, in digital journalism, an approach that delves into the causes and consequences of social movements, providing them with spaces for discussion and collective practices.

Keywords: Journalistic coverage; social movements; journalism; activism

El artículo analiza el tratamiento periodístico de los movimientos sociales en Iberoamérica en los últimos diez años (2011-2021). A fin de analizar la difusión del activismo social en la prensa, se lleva a cabo una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Así, se analizó el conjunto de fuentes, identificando en los medios informativos tradicionales un tratamiento relacionado al poder político y al refuerzo de estereotipos, y en el periodismo digital un enfoque que ahonda en las causas y consecuencias de los movimientos sociales, dotando a estos de espacios de discusión y de prácticas colectivas.

Palabras clave: Tratamiento periodístico; movimientos sociales; periodismo; activismo

O artigo analisa o tratamento jornalístico dos movimentos sociais na Ibero-América nos últimos dez anos (2011-2021). Para analisar a difusão do ativismo social na imprensa, é realizada uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Assim, analisou-se o conjunto de fontes, identificando na mídia tradicional um tratamento relacionado ao poder político e ao reforço de estereótipos, e no jornalismo digital uma abordagem que aprofunda as causas e consequências dos movimentos sociais, proporcionando-lhes espaços de discussão e práticas coletivas.

Palavras-chave: Cobertura jornalística; movimentos sociais; jornalismo; ativismo

Introduction

Journalism has changed, as have other professional areas, thanks to the phenomenon of globalization and the advance in technology. Thus, journalism has migrated from traditional channels to virtual platforms, allowing media convergence and giving way to the digital press. This is created, edited, prepared, and disseminated through online systems, and its advantages include constant updating, interactivity, and multimedia tools (Marcos Recio, 2005). Emerging journalistic media are located within this group; platforms that García (2015) classifies as “Internet native”, i.e., that are born and strengthened through the network. These models respond to the need for innovation and include new methodologies in terms of production and financing, without compromising their independence, since they are not conceived as business projects, but rather as alternative journalistic media to those belonging to large corporations (García, 2015; Marcos Recio, 2005; Marín, 2016).

The coverage of news in the media has also changed, especially in a society in which critical thinking is becoming more important. Today there are several channels of citizen connection that test the role of journalism as a key factor in the generation of public opinion and the strengthening of social criticism through collectives. These movements play an important role in the social scenario, which has forced the media sphere to transmit its facts and ideas (Almeida & Cordero, 2017). In this way, activism takes up the alter-globalization struggles and spreads new ways of hyper-connectivity. Their message is conceived and transmitted in European countries and the United States, and becomes stronger in Latin America, due to historical gaps such as inequality, poverty, and social and political exclusion (Fuentes-Nieva & Nelli Feroci, 2017; García & Bailey, 2021). In this regard, Pleyers (2018) suggests that the incidence of the press in social movements allows dividing them into four groups: indigenous and peasant movements; movements for democratization; movements for education; and movements for peace and justice.

A review of the existing theory reveals studies of the social movement-journalism binomial from the perspective of various authors. Sampedro Blanco (1997), for example, describes activism as the counterpart of political parties and bases its legitimacy on the framework of the informative agenda in the media. An initial investigation of the impact of protests in the media, between 1960 and 1999, highlights how the press went from a radical to a more moderate perspective, mainly due to the level of selection and framing of the media concerning news related to social movements (Boyle et al., 2005). Likewise, Atton (2002) presents another precedent on the interdependent social movement-journalism relationship, in which he explains that the emergence of the alternative and autonomous press responds to democratic, participatory, and counter-hegemonic needs, highlighting the emergence of the journalist-activist. The latter strengthens their ideological role with traditional and modern communicative strategies, focusing the attention on the actors of the protests as the protagonists of their own testimonies, which define the news agenda in the new media.

On the other hand, McCurdy (2012) identifies two approaches to the dynamics of social movements and the media: one is aimed at the representative level, in which the negative predisposition of the press to highlight factors such as violence and the sensationalism of protests stands out, and the other takes a relational approach to establish media strategies for the dissemination of the various activisms that are generated and strengthened mainly on the Internet. In this regard, Harlow (2013) confirms that communication channels of this network contribute to creating spaces for collective action. These organizations emerge on the political scene thanks to a social phenomenon called “fragmentation of communication networks” by Gitlin (2005). For his part, Pleyers (2018) determines that these new forms of activism are generated from collectives that use alternative media and take hold of the voice of independent journalism, which delves into progressive ideals.

With modernity, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) appear, encouraging a new logic of spatial interconnection and debate that is created and operated virtually, strengthening the development of social activism “from below” (Sampedro Blanco & Haro Barba, 2011). These social movements, in contexts of political conflict and information repression, become media that appropriate ICTs for their discursive practices, which also happens inversely: independent media that develop as platforms for social activism and can self-manage information, unlike large corporations that broadcast news (Valderrama, 2008). These changes concern activists, means of action, and the press. The role of the media is to be the setting for collective expressions that stand out for their diversity, proliferation, horizontality, creativity, and symbolism (Flores Morador & Cortés Vásquez, 2016).

According to the postulates described above, it is necessary to investigate the relationship between journalism and social movements to deepen their social role and democratic functions. In the most recent systematic review related to this topic, Rodríguez-Suárez et al. (2021) confirm that the sphere of social activism has a growing impact on digital media and their studies employ virtual ethnography as the methodology of choice. The purpose of this research is thus defined as the verification of the trend of the studies on this subject between 2011 and 2021, which presents a first state of the art that helps to understand the coverage that the media provide to social movements in Ibero-America. The analysis of the results will reflect the role played by the news media in their conciliatory function regarding the actions of social movements and their confrontation with powerful leaders.

Considering this, the main objective is to analyze the scientific papers published and disseminated through journals, repositories and academic search engines, to identify trends and establish relationships. Next, the compilation process and the analysis of results are detailed, following the systematic review method of Petticrew and Roberts (2006), whose methodology constitutes a guide for research in the field of Social Sciences, which is referenced by other authors. This is the case of Shadish (in Petticrew & Roberts, 2006), who qualifies this material as a jewel of systematic reviews since it contains not only the methodological process but also historical information, analysis of the procedure, and relevant examples in the field of research. The steps it comprises are search and evaluation; analysis and synthesis; and presentation of results (Codina, 2018).

Methodological design

To meet the initial objective, various resources were used to search for scientific articles that include studies of different realities in the world. The search platforms used during the exploration were Google Scholar, ebsco, Redalyc, SciELO, Dialnet, and RefSeek. The following key terms were used in the exploration process: “journalistic coverage”, “information”, “journalism”, “journalistic information” and “social movements”. After obtaining the first sample in Spanish, Portuguese, and English, which consisted of a total of 127 articles, the thematic bias screening was carried out.

According to Petticrew and Roberts (2006), a selection of studies can be screened based on the information obtained from the title and abstracts, as long as they are related to the research topic. Among the inclusion criteria, time with a maximum of ten years old was considered, i. e., between 2011 and 2021, a prolific period for the various fields of study, as it comprises a new stage for activist movements, thanks to protests with their own characteristics and ideas, such as those of the Arab Spring, or the youth revolts in Spain and Chile (Fuentes-Nieva & Nelli Feroci, 2017; Pleyers, 2018). The research papers found are published in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, as long as the study is carried out in Ibero-America. On the other hand, the selected documents correspond to Ibero-America, since most of the articles correspond to countries such as Spain, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina.

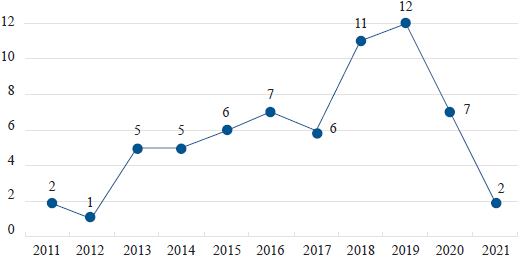

Ten articles from the first sample of studies were considered false positives and were discarded for not having thematic relevance in the research and for not reflecting the connection between journalism and activism, exclusion criteria that were taken into account in the search, as well as time and geographic space factors. Thus, 64 scientific documents were selected and tabulated to show the findings. Figure 1 shows considerable progress in studies on the journalistic coverage of social movements. Although the scientific production has been dispersed, an increase in the last four years has been validated, especially in 2019.

After validating the studies collected, the following classifications were made to obtain results in each line of research. The first categorization is related to the approach given by the media to each social movement. In this way, the aim is to verify which movements are the most relevant for the press. The articles were also grouped according to dimensions such as the type of media (written, radio, digital, etc.).

As shown in Figure 2, the feminist movement has the largest number of articles out of the total number of texts collected, with 12 documents out of 64 (18%), followed by the environmental movement, with 11 (17%), and the anti-system movements, with 10 studies (16%). At a medium level, there are social movements of popular participation such as LGBTIQ, student, animal, anti-racist, pro-independence, and teachers’ movements. Finally, movements that received little press coverage or that are not related to those described above are grouped under “Others”.

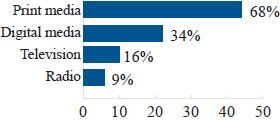

As well as examining the press messages and their social impact, it is also important to highlight the formats through which they are transmitted. After reviewing the articles, a categorization of the dimensions that correspond to the type of informative support was elaborated. Written media were the most analyzed in the research, with 44 articles out of the total (68%), followed by digital media, both Internet native media and those resulting from the so-called media convergence, with 22 articles out of 64 (34%). Television and radio, classified as traditional press, are found in smaller numbers.

To complement the study, and after categorizing the data, the results are obtained and consolidated through synthesis tables that respond to quality criteria (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). Thus, the findings of the journalistic coverage of various social movements are validated in studies with qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches, and in whose methodology various techniques, instruments, and criteria were applied, such as observation sheets, checklists, framing theory, and surveys. Based on this, summaries were prepared including the objectives, units of analysis, results, and conclusions.

The journalistic coverage of social movements in ibero-america

The procedure for conducting systematic reviews by Petticrew and Roberts (2006) meets a need that arises in the researcher to comprehensively and impartially summarize all the existing information on a phenomenon. The exploratory process has shown that the articles are studies that employ a variety of methodologies, going from observation to experimentation, besides having qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches. Thus, it has been decided to describe the main results of those studies that are relevant for drawing conclusions, which are categorized and detailed below.

Journalistic coverage by social movement

The social movement most talked about in the Ibero-American press over the last ten years has been feminism. Beyond the debate on the ideological conceptualization of this movement, this research seeks to establish its relationship with journalism. The documents observe the presence of women and the relevance of their inclusion on the road to gender equality and equity, based on historical and commemorative facts. The study by Gómez y Patiño (2017) presents a comparative analysis of the Aragonese press, in Spain, between 2007 and 2013, finding an alternation of feminist topics due to social pressure and the government in power.

Undoubtedly, one of the countries in the region where this issue has been the most discussed in the media has been Argentina. A turning point has been the “Ni una menos” (“Not one less”) collective and the marches called by this group. Studies by Fernández Hasan (2016), Cabral and Acacio (2016), and Romero Piskorz (2019) address these protest demonstrations generated from the Internet, and also highlight their dissemination in traditional and non-traditional media, being spaces where the news generates debate, both in the impact of the stories, and in the effects of the marches. In general, the coverage was total, although with a greater reach in digital media due to the horizontal communication between the actors.

Table 1 Journalistic coverage of feminist movements

| Author(s) | Main results |

| Bernal-Triviño (2019) | The analyzed media reinforce informative stereotypes about women and gender violence, turning the case of Juana Rivas into a sample of “media violence”, which omits awareness-raising details of those involved, as well as the invalidity of the judicial proceedings on this issue. |

| Fernández Hasan (2016) | The study highlights networks of journalists in favor of feminist approaches in communication, such as the par Network and the ripvg network. The activity of these and other groups enables feminist practices (the “Ni una menos” collective is highlighted) and fosters a new space for dialogue. |

| Gómez and Patiño (2017) | There is an alternation of the term woman, and in general of feminist issues, in the media analyzed from an external factor of the local area. There is also a concordance, analyzed from the agenda-setting, between the media and the current government. |

| Liarte Marín and Bandrés Goldaráz (b2019) | Units of study from three media and their coverage of the “La Manada” case were collected: comparing traditional media and a digital native one. The latter showed greater objectivity, and the use of more graphic resources, infographics, and videos. |

| Cabral and Acacio (2016) | The results indicate that current journalistic coverage has two approaches: one that portrays the crude reality of gender violence, both cases of abuse against women and feminicide; and, on the other hand, the effect of feminist movements in Argentina. |

| Romero Piskorz (2019) | It is concluded that the “Ni una menos” (“Not one less”) collective received overwhelming coverage by the press, especially by the digital media, where a more horizontal line of communication is developed, which allows for the strengthening of activism. |

| Tello Divicino et al. (2018) | It was concluded that women were made invisible in the public work of activism, which belonged to the fathers. They, however, were related to intimate and emotional environments. In this way, the patriarchal discourse prevailing in the regional press was reinforced. |

| Clavijo Sanabria and Barredo Ibáñez (2019) | It is reported that the website of the radio station analyzed preferred to publish short articles in the written press, while more extensive audios were broadcasted. The interest in the case was decreasing, performing the function of a description of the facts, generating debate on social networks. |

Source: The authors.

The second social movement that dominated the media in Ibero-America between 2011 and 2021 was the environmental movement. The press coverage focused on social conflicts that originated from mining projects in countries where this extractive activity predominates, such as Peru. The articles by Huamán (2013), Gonzales García (2017), and Acevedo (2013) address this problem by detailing the absence of companies as sources of the news and that the commercial relationship of these with the media disappears objectivity. On the other hand, the studies follow the framing theory, which highlights the confrontational framing, giving the responsibility for the social crisis to the leaders and protesters, even to the point of criminalization.

For this systematic review, the anti-system movement is considered to be all those citizen demonstrations that arise in defense of human rights and declare a system of social, political, and economic order in crisis (Fernández Buey, 2009). Undoubtedly, one of the most publicized protests in Spain was the one that took place on May 15th, 2011, and was replicated in other cities. The articles by Moreno Ramos (2013), Castillo Esparcia et al. (2013), García-Arranz (2014), and Barranquero Carretero and Meda González (2015) analyze their impact on the news media, concluding that conventional media are more concerned with the political impact of demonstrations, while non-conventional media develop a more innovative coverage focused on the protagonists.

Table 2 Journalistic coverage of environmental movements

| Author(s) | Main results |

| Huamán (2013) | It was found that there is an absence of the company as a source of news. On the other hand, regional journalism responds to the interests of the editorial line, while local journalism, especially radio, opines more and responds to ratings. The frames were always conflictive and confrontational. |

| Gonzales-García (2018) | It is concluded that throughout the study period, it was determined that there is a greater media concentration on the expectations regarding the organization and holding of the summit than on the possible impacts or consequences of the phenomenon. |

| Cabello et al. (2018) | The results indicate that the movement is focused on the socio-environmental conflict, and emphasize that the origin of the crisis lies in the productive model of the area. On the other hand, the analyzed press media denote important frames: the natural phenomenon, the protest, and the lack of public safety. |

| Teso Alonso and Fernández-Reyes (2020) | The environmental movements have been covered by the Spanish media, identified as progressive, especially La Sexta and El País, with the news and the report as the predominant genres. |

| Gonzales García (2017) | The news media arbitrarily addressed the environmental movements, attributing responsibility to labor unions and leaders, and justifying the defense of the mining company. In this way, for the press, the actors of the social protest were guilty of disturbing the political and social order of the country. |

| Acevedo (2013) | The analyzed media lack independence and journalistic rigor since they are not economically sound, which forces their owners to support one of the two parties in dispute, especially if they have a commercial relationship with the media. |

| Herranz de la Casa et al. (2018) | There is a constant focus of the newspapers on social activity. The monitoring of the press allows for deducing meetings with political representatives. On the other hand, some differences between the anti-fracking group are highlighted: the focus is on ngos rather than collectives. |

Source: The authors.

Another wave of demonstrations that broke out in 2011 was the so-called Arab Spring, protests that were replicated in several countries in the Middle East and made headlines in several news media in Ibero-America (Córdoba Hernández, 2015; Córdoba Hernández & Durán Camero, 2016; Corral et al., 2020). The findings indicate that press coverage prioritized the demonstrations in Egypt. The news media used anti-democratic adjectives for the presidents and terms such as “massive” and “peaceful” to qualify the protests. On the other hand, subtle Islamophobia was detected in the press when referring to the incompatibility between Islam and democracy. The articles analyzed show that this was a global and contagious social phenomenon that transcended geographical and political borders.

It was found that most of the articles collected, whose theme is related to sexual minorities and their struggle for equality, are studies developed in Spain. News coverage of relevant events in the gay community, such as the World Pride Madrid 2017 and Pride Barcelona 2018 marches are evaluated by Sánchez Soriano and Sánchez Castillo (2019), and Huertas Bailén and Theodoro (2019), respectively. It can be seen that the media focused on the demonstrations and victimization of those involved, consolidating their nature as individuals in need of biopolitical management by the power agencies. Despite enunciating cultural references to the struggle and celebration of the LGBTIQ collective, these gatherings only acquire relevance when public and political figures participate.

Table 3 Journalistic coverage of anti-system movements

| Author(s) | Main results |

| Moreno Ramos (2013) | It is concluded that conventional media are more concerned with the political impact of the protests, while non-conventional media portray a more innovative and protagonist-focused coverage. |

| Córdoba Hernández (2015) | Egypt is the best-known country to the Western media; therefore, this nation gained prominence during the social movements in several Middle East countries, revolts known as the “Arab Spring”. International news agencies were largely used in this media coverage and the female participation in the protests was symbolically focused. |

| Corral et al. (2020) | It is stated that Islamophobia appears subtly in the informative approach of some journalistic media, focusing the discourse of the anti-system movement on political Islamism, as well as on the incompatibility between Islam and democracy. |

| Castillo Esparcia et al. (2013) | Two social movements are compared and it is detailed that the Spanish movement focused more on action than on analytical depth, while the U.S. movement had more qualitative information from experts and a focus on economic demands. |

| García-Arranz (2014) | The analyzed newspapers are not only basic enunciation actors in the protest process, but they also develop their analytical validity as reference spaces. In this way, the media not only supported the dissemination of the discourses of the outraged population but also allowed for debate, especially on opinion pages and microblogging platforms. |

| Barranquero Carretero and Meda González (2015) | The emergence of new tools has helped shorten distances and allow demonstrations to be replicated in more places. According to respondents, coverage was coordinated through non-face-to-face channels, and solidarity and community economy. |

| Córdoba Hernández and Durán Camero (2016) | The media coverage of the news enhanced the visibility of the demonstrations, presenting disparate and seemingly geographically and politically distant movements as a global and contagious phenomenon that transcended borders. |

Source: The authors.

One of the most important achievements of the LGBTIQ movement in Spain was the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2005, becoming the third country in the world to do so, after the Netherlands and Belgium. The study by Díaz-Campo (2019) makes findings around the press coverage of that law and its permanence over the years. For his part, Carratalá (2011) investigates the case of a plane crash in 2008 in which a media gay couple, whose marital bond was almost made invisible by the media, died. Both articles reinforce the hegemonic character of traditional sexuality in the news, as well as demonstrate a constant confrontation between secular and Catholic societies.

Table 4 Journalistic coverage of LGBTIQ movements

| Author(s) | Main results |

| Huertas Bailén and Theodoro (2019) | The representations disseminated by the press focus on the victimization of those involved and consolidate their nature as people who require biopolitical management and who are unable to make their own decisions. |

| Díaz-Campo (2019) | It is concluded that in Spain there is a strong confrontation between secular and Catholic societies, taking the discussion to the religious level. The author indicates that none of the media showed true independence and that editorial is the most used genre for this purpose. |

| Carratalá (2011) | According to the article, there are cases in which the gay relationship analyzed is kept hidden, using euphemistic terms, preventing readers from an accurate understanding of the facts and it confirms that the cultural context continues to privilege the hegemonic sexuality. |

| Sánchez Soriano and Sánchez Castillo (2019) | There is a balanced view of the analyzed event. Several referents of the LGBTIQ collective are mentioned and the focus is placed on the demonstrations, which have more acceptance, especially due to the participation of different political parties and public figures. |

Source: The authors.

After drawing the main results of the most widely covered social movements in the news field, those related to other protests in the region and whose conclusions can be used to support this research are presented. Firstly, articles on the student movement in Chile and its impact on the local media were collected, where signs of sensationalism and incitement to hatred of youth collectives were found, qualifying them under the metaphor of the encapuchados (hooded), criminalizing their actions as individuals with antisocial purposes who constantly reproach the authority with the use of violence, and who resisted the onslaught of the traditional press through digital platforms (Browne Sartori et al., 2015; Cárdenas & Pérez, 2017; Cárdenas-Neira, 2016).

Another movement that has gained prominence in recent years has been the anti-racist one. The article by Hamas Elmasry and el-Nawawy (2016) addresses the issue of racial minorities in the United States, explaining that there is a different approach due to a historical change in American society since 2014 and that remains in force to this day. Machado da Silva and Cezar de Campos (2019), instead, analyze the racism found in the admission process to the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil. The journalistic media studied did not criminalize the protests carried out by the “Negro Balanta” collective; however, none of them were able to delve into ideological positions, causes or consequences, since they only reported the facts.

The journalistic coverage of social movements by type of press

The verification of the articles considered in this systematic review made it possible to define and compare the formats through which the media disseminate the actions, motives, and effects of social movements in Ibero-America. Many of the investigations tend to establish a comparison between traditional or conventional media (written newspapers, television, and radio) and non-traditional or non-conventional media (digital journalism, social networks). The genres that achieve greater relevance and allow greater effectiveness in informative messages are the news piece, the report, and the editorial (Díaz-Campo, 2019; Teso Alonso & Fernández-Reyes, 2020).

The written media analyzed, mainly newspapers and weeklies, have a limitation principle compared to the media that have emerged from the Internet. Despite this, they are still considered reliable sources of information. According to Raimondo Anselmino et al. (2018), there is a very dissimilar level of mediatization between information platforms, highlighting print journalists for being more careful with the material they are going to disseminate. Concerning social movements, most newspapers are concerned about dealing with these issues and seek to sell a headline or a cover that attracts attention, from the impact of the conflict and the generation of tension, since they have lost ground against digital media (Amenta et al., 2017; Rodríguez et al., 2014).

Television media, for their part, continue this same line of conventionalism and sensationalism, especially in countries such as Chile, where student and socio-environmental protests are portrayed as conflict zones, reinforcing stereotypes of violence and using multimodal metaphors that are disseminated with textual, visual and sound elements (Cárdenas Neira & Pérez-Arredondo, 2018; Rodríguez et al., 2014). Meanwhile, Arévalo Salinas & López Ferrández (2015) conclude that, in Spain, the news programs of television channels make emphasis on promoting transversality and pacifism in their contents, as an alternative representation of demonstrations and a more human portrayal of protesters and victims.

In the case of radio media, radio stations are defined as immediate channels for the dissemination of social conflicts and the generation of debate through the opening of citizen dialogue. Huamán (2013) confirms that journalistic programs on the radio opine more while still responding to ratings. An example of this is that microphones are open for public participation, especially in regional media and in response to local conflicts. Clavijo Sanabria and Barredo Ibáñez (2019) highlight that, broadcasters have strengthened their convergence stage and many of them use web platforms and social networks.

Currently, it is very difficult to differentiate between the digital media resulting from the convergence of technology and those that were born and strengthened on the Internet. However, it is clear that the latter tend to be more concerned about immediacy, innovation, and allowing the news related to social movements to connect beyond the local level, developing a horizontal communication line and strengthening activism (Moreno Ramos, 2013; Romero Piskorz, 2019). When there is news demanding a large volume of information, approaches, interviews, and opinions, the digital press resorts to its tools and resources ranging from graphics, infographics, and audiovisual material, among others, allowing hypertextuality of the message and transmedia narrative (García-Arranz, 2014; Liarte & Bandrés, 2019).

These results describe the Ibero-American reality and are contrasted with the situation in other continents. For example, the study by Gheytanchi and Moghadam (2014) reflects how social collectives composed of women are organized in the Middle East and North Africa. As well as in this research, it is highlighted the role of social networks to convene protesters of feminist movements, as in the case of the “Ni Una Menos” (“Not one less”) collective, in which the existing links between cyberactivism and digital journalism are enhanced (Cabral & Acacio, 2016; Fernández Hasan, 2016; Romero Piskorz, 2019).

Likewise, the article by Höglund and Schaffer (2021) understands social activism as a tool that defends freedom of expression in Uganda since the collectives confront authoritarianism as a sign of solidarity with the press, something that differs from the collective motivations developed in the region mentioned in this study. Finally, Sala (2018), in his systematic review of social movements in Europe, states that currently their negative imaginary has changed, and the efficacy of the collective and the debate developed through the media is highlighted. This deduction is present in Ibero-American journalism as long as it operates through alternative media and the Internet.

Conclusions

Based on the report on the preparation of systematic reviews by Petticrew and Roberts (2006), this article has elaborated a collection and analysis of studies on the journalistic coverage of social movements in Ibero-America, carried out between 2011 and 2021. There is a trend toward an increasingly stronger insertion of social movements in the various spheres of the news and in journalistic media that emerge through digital platforms, which act as collaborative practices of activism. The news media that are broadcasted on the Internet, especially the so-called Internet native media, consider the issue of citizen protest demonstrations as a relevant topic. While in traditional media companies the focus is related to political issues, in digital media there is incipient activist journalism that is more concerned with racial and ideological minorities.

It was found that since 2011 there has been an increase in publications related to social movements in the region. The discussion of these topics in research articles has been constant in the last ten years and has been promoted in different fields of study due to citizen movements such as the Arab Spring in the Middle East or the 15-M marches, and the Catalan independence process in Spain. In the following years, the phenomenon of feminism emerged in countries such as Argentina, and socio-environmental and student struggles were reinforced in Peru and Chile, respectively. Most of the protests were called and reinforced their discourse through Internet platforms and social networks.

According to the academic articles analyzed, movements associated with ideological currents such as feminism, environmental groups, and the LGBTIQ movement, received greater coverage and acceptance in the Ibero-American news media; although in some studies associated with homosexual marriage, the use of euphemistic terms and the bias of sexual freedom due to religion remain in force. It was determined that the media reinforces stereotypes of women and their domestic characteristics in Mexico, and of the criminalization of peasants and students in Peru and Chile, in which conflict and violence are highlighted.

According to the articles analyzed, especially those related to feminist movements, there are notorious differences between traditional and non-traditional media. Thus, there are two groups: the media that are more concerned with the consequences of the marches and their political and economic repercussions, and the media focused on the organization of the activists. In many research studies, it is perceived that the so-called conventional media have no independence and respond to economic and political interests, so they only focus on the dissemination of facts and do not delve into the analysis of the causes and consequences of social movements. On the other hand, the non-conventional media prefer to delve into the different aspects of social activism, to generate a debate of opinions on the Internet, being on the side of the protester. The need for future reviews from this and other perspectives to explore the communicative phenomena and their implications in the diverse collectives that today attract the attention of the world through their social actions is highlighted.

REFERENCES

Acevedo, J. (2013). Conga: un tiempo después. Medios de comunicación, conflicto y diálogo en Cajamarca. Conexión, (2), 150-167. http://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/conexion/article/view/11570 [ Links ]

Almeida, P. & Cordero, A. (2017). Movimientos sociales en América Latina. Clacso. [ Links ]

Amenta, E., Elliott, T. A., Shortt, N., Tierney, A. C., Türkoğlu, D. & Vann Jr., B. (2017). From bias to coverage: What explains how news organizations treat social movements. Sociology Compass, 11(3), e12460. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12460 [ Links ]

Arévalo Salinas, A. & López Ferrández, F. J. (2015). Movimientos sociales y periodismo en España. Una propuesta pacífica y transversal. Revista Interdisciplinar de Direitos Humanos, 3(1), 87-102. http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/159482 [ Links ]

Atton, C. (2002). News Cultures and New Social Movements: radical journalism and the mainstream media. Journalism Studies, 3(4), 491-505. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1461670022000019209 [ Links ]

Barranquero Carretero, A. & Meda González, M. (2015). Los medios comunitarios y alternativos en el ciclo deprotestas ciudadanas desde el 15M. Athenea Digital, 15(1), 139-170. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.1385 [ Links ]

Bernal-Triviño, A. (2019). El tratamiento informativo del caso Juana Rivas. Hacia una definición de violencia mediática. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 25(2), 697-710. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.64797 [ Links ]

Boyle, M., McCluskey, M., McLeod, D. & Stein, S. (2005). Newspapers and Protest: An Examination of Protest Coverage from 1960 to 1999. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(3), 638-653. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F10776990050820031 [ Links ]

Browne Sartori, R., Romero Lizama, P. & Monsalve Guarda, S. (2015). La cobertura regional del movimiento estudiantil chileno 2011: prensa impresa y prensa digital en La Región de Los Ríos (Chile). Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 21(2), 723-740. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2015.v21.n2.50881 [ Links ]

Cabello, P., Torres, R. & Mellado, C. (2018). Conflicto socioambiental y contienda política: encuadres de la crisis ambiental de la marea roja en Chiloé (Chile). América Latina Hoy, 79, 59-79. https://doi.org/10.14201/alh2018795979 [ Links ]

Cabral, P. & Acacio, J. A. (2016). La violencia de género como problema público. Las movilizaciones por “Ni una menos” en la Argentina. Memoria Académica, 1(51), 170-187. http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.8458/pr.8458.pdf [ Links ]

Cárdenas-Neira, C. (2016). Representación de la acción política juvenil en redes sociales: Análisis crítico de las prácticas discursivas producidas durante las movilizaciones estudiantiles en Chile (2011-2013). Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales, (30), 77-99. https://doi.org/10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.2016.n30-04 [ Links ]

Cárdenas, C. & Pérez, C. (2017). Representación mediática de la acción de protesta juvenil: la capucha como metáfora. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(2), 1067-1084. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.1521814092016 [ Links ]

Cárdenas Neira, C. & Pérez-Arredondo, C. (2018). Recontextualización multimodal de las acciones y motivaciones del movimiento estudiantil chileno en un reportaje de televisión. Literatura y Lingüística, (37), 217-236. https://doi.org/10.29344/0717621X.37.1381 [ Links ]

Carratalá, A. (2011). La representación eufemística de la relación gay en el periodismo serio. Miguel Hernández Communication Journal, (2), 155-172. https://doi.org/10.21134/mhcj.v1i2.36 [ Links ]

Castillo Esparcia, A., García Ponce, D. & Smolak Lozano, E. (2013). Movimientos sociales y estrategias de comunicación. El caso del 15M y de Occupy Wall Street. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 19(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2013.v19.n1.42508 [ Links ]

Clavijo Sanabria, A. & Barredo Ibáñez, D. (2019). Opinión pública y movilización en Colombia. Estudio sobre el impacto del caso de Yuliana Samboní en la W Radio. Cuadernos Artesanos de Comunicación, 155-188. https://repository.urosario.edu.co/handle/10336/28823 [ Links ]

Codina, L. (2018, 11 de abril). Revisiones sistematizadas para trabajos académicos · 1: Conceptos, fases y bibliografía [entrada de blog]. Lluís Codina. https://www.lluiscodina.com/revisiones-sistematizadas-fundamentos/ [ Links ]

Córdoba Hernández, A. M. (2015). La fotografía y el texto en la construcción del framing de la Primavera Árabe: un análisis del cubrimiento y tratamiento informativo de la prensa de referencia Colombiana, en 2011. Observatorio (OBS*), 9(2), 149-172. https://doi.org/10.15847/OBSOBS922015798 [ Links ]

Córdoba Hernández, A. M. & Durán Camero, M. (2016). El efecto dominó de las revueltas sociales de 2011 visto desde la prensa de referencia colombiana. Anagramas, 14(28), 135-166. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v14n28a8 [ Links ]

Corral, A., Fernández Romero, C. & García Ortega, C. (2020). Framing e islamofobia. La cobertura de la revolución egipcia en la prensa española de referencia (2011-2013). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (77), 373-392. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1463 [ Links ]

Díaz-Campo, J. (2019). Tratamiento de la legalización del matrimonio homosexual en la prensa española desde la perspectiva del “framing”. Análisis comparado de “ABC” y “El País”. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 25(1), 459-475. https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.63740 [ Links ]

Fernández Buey, F. (2009, 12 de abril). ¿Es tan malo ser antisistema? Público. https://blogs.publico.es/dominiopublico/1208/es-tan-malo-ser-antisistema/ [ Links ]

Fernández Hasan, V. (2016). El ingreso de la agenda feminista a la agenda de los medios. La Trama de la Comunicación, 20(2), 127-143. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=323946840007 [ Links ]

Flores Morador, F. & Cortés Vásquez, J. (2016). Los nuevos movimientos sociales, el uso de las TIC y su impacto social. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (71), 398-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2016-1101 [ Links ]

Fuentes-Nieva, R. & Nelli Feroci, G. (2017). Los movimientos sociales en América Latina y el Caribe, la evolución de su papel e influencia, y su creciente fuerza. International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de developpement, 9. https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2511 [ Links ]

García, K. A. (2015). Principios organizadores en seis medios periodísticos emergentes en internet. Nexus, 1(17), 112-129. https://doi.org/10.25100/nc.v1i17.702 [ Links ]

García, L. & Bailey, O. G. (2021). 20 años de estudio sobre los medios de movimientos sociales, internet y redes sociodigitales en América Latina. Espiral Estudios Sobre Estado y Sociedad, 28(81), 9-42. http://espiral.cucsh.udg.mx/index.php/EEES/article/view/7124/6374 [ Links ]

García-Arranz, A. M. (2014). La opinión publicada sobre el movimiento 15-M. Un análisis empírico de los periódicos digitales españoles: elmundo.es, elpais.com y abc.es. Palabra Clave, 17(2), 320-352. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2014.17.2.3 [ Links ]

Gheytanchi, E. & Moghadam, V. (2014). Women, social protests, and the new media activism in the Middle East and North Africa. International Review of Modern Sociology, 40(1), 1-26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43496487 [ Links ]

Gitlin, T. (2005). Enfermos de información. De cómo el torrente mediático está saturando nuestras vidas. Paidós. [ Links ]

Gómez y Patiño, M. (2017). Narrativa política en torno a la mujer (8-M). Análisis comparado (2007-2013). Sphera Publica Revista de Ciencias Sociales y de la Comunicación, 1(17), 132-147. http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/download/298/276 [ Links ]

Gonzales García, C. R. (2017). Las movilizaciones sociales en el Perú desde la perspectiva del framing. Horizonte de la Ciencia, 7(12), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.26490/uncp.horizonteciencia.2017.12.324 [ Links ]

Gonzales-García, C. (2018). Tratamiento periodístico del cambio climático en los diarios peruanos El Comercio y La República (2013-2017). Comunicación y Medios, 2788(38), 27-36. https://comunicacionymedios.uchile.cl/index.php/RCM/article/view/50829 [ Links ]

Hamas Elmasry, M. & el-Nawawy, M. (2016). Do black lives matter? A content analysis of New York Times and St. Louis Post-Dispatch coverage of Michael Brown protests. Journalism Practice, 857-875. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1208058 [ Links ]

Harlow, S. (2013). It was a ‘Facebook revolution’: Exploring the meme-like spread of narratives during the Egyptian protests. Revista de Comunicación, (12), 59-82. https://revistadecomunicacion.com/en/articulos/2013/Art059-082.html [ Links ]

Herranz de la Casa, J. M., Álvarez-Villa, À. & Mercado-Sáez, M. T. (2018). Communication and effectiveness of the protest: Anti-fracking movements in Spain. Zer: Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 23(45), 35-56. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.19543 [ Links ]

Höglund, C.-M. & Schaffer, J. K. (2021). Defending Journalism Against State Repression: Legal Mobilization for Media Freedom in Uganda. Journalism Studies, 22(4), 516-534. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1882879 [ Links ]

Huamán, L. (2013). Los medios de comunicación en conflictos sociales: el tratamiento periodístico del conflicto socio-ambiental Quellaveco. Canalé, (5), 52-59. http://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/canale/article/view/14708 [ Links ]

Huertas Bailén, A. & Theodoro, H. (2019). Tratamiento periodístico de personas LGTBIQ+ refugiadas: estudio de caso sobre Pride Barcelona 2018. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, (46), 48-65. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2019.i46.04 [ Links ]

Liarte Marín, C. & Bandrés Goldaráz, E. (2019). La objetividad y neutralidad de la información en la red: el tratamiento del Diario.es, ABC.es y El País.com en el juicio contra «La Manada». Fonseca, Journal of Comunication, (18), 119-140. https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc201918119140 [ Links ]

López-Olano, C. & Fenoll, V. (2019). Posverdad, o la narración del procés catalán desde el exterior: BBC, DW y RT. El Profesional de la Información, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.may.18 [ Links ]

Machado da Silva, W. & Cezar de Campos, D. M. (2019). Os dois lados do espelho: a cobertura midiática e as publicações do coletivo Negro Balanta no embate sobre as cotas na UFRGS. Revista Prâksis, 1, 123-143. https://doi.org/10.25112/rpr.v1i0.1734 [ Links ]

Marcos Recio, J. (2005). De la prensa digital a la prensa gratuita emergente: aspectos informativos y documentales. Boletín de la ANABAD, LV(1-2), 153-170. https://www.anabad.org/wp-content/uploads/2005.1-2.pdf [ Links ]

Marín, A. (2016). Periodismo emergente: atención al usuario, calidad e hibridación. Estudio del caso Revista 5W en España. En P. Moreno Espinosa (Ed.), Comunicación, ciberperiodismo y nuevos formatos multimedias interactivos (pp. 32-47). Ediciones Egregius. [ Links ]

McCurdy, P. (2012). Social Movements, Protest and Mainstream Media. Sociology Compass, 6(3), 244-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00448.x [ Links ]

Moreno Ramos, M. Á. (2013). Tratamiento periodístico del Movimiento 15-M en medios de comunicación alternativos y convencionales. Mediaciones Sociales, (12), 160-187. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_MESO.2013.n12.45267 [ Links ]

Petticrew, M. & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887 [ Links ]

Pleyers, G. (2018). Movimientos sociales en el siglo XXI: perspectivas y herramientas analíticas. CLACSO. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20181101011041/Movimientos_sociales_siglo_XXI.pdf [ Links ]

Raimondo Anselmino, N., Reviglio, M. C. & Echecopar, C. M. (2018). #RosarioSangra en la prensa: Análisis de la puesta en discurso de movilizaciones ciudadanas. Revista Chilena de Semiótica, (8), 25-47. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/99930 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, R., Peña, P. & Sáez, C. (2014). Crisis y cambio social en Chile (2010-2013): el lugar de los medios de los movimientos sociales y de los activistas digitales. Anagramas, 12(24), 71-93. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v12n24a4 [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Suárez, J., Morán-Neches, L. & Herrero-Olaizola, J. B. (2021). Investigación en red, nuevos lenguajes y simbologías del activismo digital: Una revisión sistemática. Comunicar, (68), 47-58. https://doi.org/10.3916/C68-2021-04 [ Links ]

Romero Piskorz, M. (2019). Los medios de comunicación y el tratamiento de los temas de género en Argentina después del “Ni Una Menos”. Cuadernos de Comunicólogos, (7), 42-52. https://www.comunicologos.com/revista/revista-2019/ [ Links ]

Sala, E. (2018). Crisis de la vivienda, movimientos sociales y empoderamiento: una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(1), 99-126. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.379 [ Links ]

Sampedro Blanco, V. (1997). Movimientos sociales. Debates sin mordaza. Desobediencia civil y servicio militar (1970-1996). BOE Editorial. [ Links ]

Sampedro Blanco, V. F. & Haro Barba, C. (2011). Activismo político en Red: del Movimiento por la Vivienda Digna al 15M. Teknokultura. Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 8(2), 157-175. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/5372430.pdf [ Links ]

Sánchez Soriano, J. J. & Sánchez Castillo, R. (2019). Tratamiento informativo del Word Pride Madrid en las cadenas generalistas en España. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 25(2), 1087-1102. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.64827 [ Links ]

Tello Divicino, A. L., Morales Jiménez, M. V. & Quintero Romero, D. M. (2018). El discurso periodístico de la participación de las mujeres en el movimiento de los 43. Cuestiones de género: de la igualdad y la diferencia, (13), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.18002/cg.v0i13.5401 [ Links ]

Teso Alonso, M. G. & Fernández-Reyes, R. (2020). Las Imágenes de las Movilizaciones Climáticas Juveniles en la Prensa y la Televisión en España. Historia Ambiental Latinoamericana y Caribeña (HALAC), 10(3), 108-149. https://doi.org/10.32991/2237-2717.2020v10i3.p1 08-149 [ Links ]

Valderrama, C. E. (2008). Movimientos sociales: TIC y prácticas políticas. Nómadas, (28), 94-101. https://bit.ly/3Amv0mb [ Links ]

How to cite:

Mamani Gómez, M. E. & Pérez Baca, J. E. (2022). The journalistic coverage of social movements in Ibero-America. Comunicación y Sociedad, e8166. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8166

Received: June 01, 2021; Accepted: October 07, 2021; Published: August 17, 2022

text in

text in