Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub 03-Oct-2022

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8188

Articles

Medios de comunicación y compromiso político

Communicative ecology of the #YoPrefieroElLago movement: an approach from private, independent, and alternative media

1 Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, México. clemus@docentes.uat.edu.mx

The purpose of this paper is to describe the characteristics of the content generated by private, independent, and alternative media around the controversy over the construction of Mexico City’s new airport in 2018, to identify the communicative ecology of #YoPrefieroElLago movement. This work was developed under a quantitative exploratory descriptive methodology. A content analysis was performed over 905 publications on web pages and 8 402 tweets. The results showed that the third sector takes part of the connecting actions of the movement.

Keywords: Third sector; media; digital activism; media ecology

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo describir las características de los contenidos generados por medios privados, independientes y alternativos en torno a la controversia por la construcción del Nuevo Aeropuerto de la Ciudad de México en el 2018, con el fin de identificar la ecología comunicativa del movimiento #YoPrefieroElLago. La metodología empleada es cuantitativa exploratoria-descriptiva. Se realizó un análisis de contenido de 905 publicaciones en páginas web y 8 402 tuits de diversos medios de comunicación. Los hallazgos muestran que el tercer sector participa de forma significativa en las acciones conectivas del movimiento social.

Palabras clave: Tercer sector; medios de comunicación; activismo digital; ecología mediática

O objetivo deste artigo é descrever as características do conteúdo gerado pela mídia privada, independente e alternativa em torno da polêmica sobre a construção do Novo Aeroporto da Cidade do México em 2018, para identificar a ecologia comunicativa do movimento #YoPrefieroElLago. Este trabalho foi desenvolvido sob uma metodologia quantitativa exploratória descritiva. Foi realizada uma análise de conteúdo de 905 publicações em páginas da web e 8 402 tweets. Os resultados mostraram que o terceiro setor faz parte das ações de articulação do movimento.

Palavras-chave: Terceiro setor; mídia; ativismo digital; ecologia midiática

Introduction

Digital activism refers to a wide range of collective behaviors that involve protest forms and actions, based on the Internet and supported by it, from which a social movement achieves an interaction between diverse actors (Van Laer & Van Aelst, 2011). The communicative dimension of this process is important in the organizational practices inside the movement, as well as in the setting of the contention repertoires that allows the construction of a framework for the confrontation with its antagonists (Tilly & Wood, 2010).

In the current scenario of digital convergence and connective actions (van Dijck et al., 2018), several research studies have presented the complex relations network that interweave in the construction of a social movement’s “communicative ecology” (Mattoni, 2017), pointing out that the reductionist or one-dimensional perspectives on the repertoires or spaces of collective action do not contribute to pose the numerous angles that this type of process entails (Treré, 2020; Trillos & Soto-Molina, 2018). Particularly, when it comes to a discursive confrontation in which multiple actors intervene -proposing arguments from different lifeworlds and rationalities-, the analysis of the multiple communicative interaction scenarios become key for a global analysis of the communication strategy of social movements (Candón & Benítez, 2016; Kidd & McIntosh, 2016; Lim, 2018).

Communicative ecology refers to a “theoretical proposal that aims to objectively describe the setting or communicative environment of today, framing it in the effect that these have on the subjects that use them” (Giraldo-Dávila & Maya-Franco, 2016, p. 750). Hence, we depart from the idea that there are reciprocal interactions between communicative processes and users, being the digital scenario an environment with overlapping discourses, actions, and symbols, in which a multiplicity of actors and narratives converge. Therefore, “ecology implies an environment that combines structure, content and impact on users” (Scolari, 2015, p. 29); this, placed in the communication field, would indicate that current news production generate informative processes that pose a reciprocal determination between the communication environment and those who communicate. In the analysis of the communicative ecology of a social movement, the framing process requires a multilevel analysis, both inside and outside the network (Millaleo & Velasco, 2013), drawing attention to the networks of power that run through the different actors.

In this article, we propose that the framing process in a social movement has different configurations, based on the type of actor and media that participates in the discursive confrontation. To classify the type of actor, it is possible to choose from several criteria: ownership (private/for-profit, public, or social); type of topics they address; or, as proposed in this work, the nature of their news information construction process. In the case of this paper, the privately owned/for profit, independent and alternative media are the three main points of tension to be compared and described.

Firstly, the characteristics of privately owned/for-profit media are the commodification of their content, the process of searching for opinions that counterpoint each other, and their links to a clear political agenda aligned with the editorial line of the media owners (Gómez, 2018). Independent media, conversely, arise from journalistic projects without a government or corporate funding that, even though they function as companies and are not against the sale of advertising, champion a production of journalistic contents -frequently linked to the investigative type- with a high sense of citizen participation and public service (Martínez-Mendoza & Ramos, 2021). Finally, the alternative media constitute a wide array of media characterized by having a counter-hegemonic nature in the production of their content, and that, in terms of their financing, even reject the sale of advertisement, establishing a very close relationship with their user community, with which they establish financial, participation and horizontal relations (Barranquero & Candón, 2021).

Thus, the focus of this paper is on elucidating the role played by alternative media in the scheme of the communicative ecology of a social movement, since their political approach is associated with an active dissemination of information linked to social movements. (Candón, 2013; Ramos-Martín et al., 2018). Alternative media are a key agent in the discursive process of a particular social movement and in the “hybridization” in the media scene (Chadwick, 2013), where often conflicting discourses and logics are negotiated; therefore, it is necessary to identify communicative interactions from a procedural and multilevel perspective.

Consequently, this paper describes, in order to identify the communication process from the array of actors and interaction scenarios that are part of a social movement, the characteristics of the content generated by these three types of media. The case of study will be, in this instance, the controversy that occurred between October 23rd and 30th, 2018, over the construction of the Nuevo Aeropuerto de la Ciudad de México (New Airport of Mexico City), comparing the informative process within web pages posts of each type of media and the interactions generated in the Twitter social network for the same actors.

Background for #YoPrefieroElLago

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) won the Mexican presidential elections on July 2nd, 2018. He began, even before taking office, a series of actions and statements aligned with the slogan of “a new national project”, amongst which were the reorientation of megaprojects from the previous administration of former president Enrique Peña Nieto. One of them, the Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de la Ciudad de México or New International Airport for Mexico City (NAICM), was set for a popular referendum between October 25th and 28th, as a part of participatory democracy actions unprecedented for the country.

The controversy that arose from this citizen consultation exercise and its relevance for the analysis of the communicative actions of a social movement are multifactorial. Firstly, because the NAICM works had been underway since 2016 and the construction of the terminal building had a 60% progress (Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes [SCT], 2016). As of 2018, according to the Auditoría Superior de la Federación (Superior Auditor of the Federation), the investment in the project was just over 190 million Mexican pesos; almost 300 companies had construction contracts in force at the moment of the consultation; and four afore retirement funds (similar to 401k) invested savings of Mexican workers in the project (Auditoría Superior de la Federación [ASF], 2021).

However, the transitional government saw the cancellation of the project as an important area of opportunity to underline the failures of the previous administration in terms of its efficiency. They presented evidence that building two runways at the military airbase in Santa Lucía, State of Mexico, had lower construction and maintenance costs, better operating conditions, and less environmental impact, since the NAICM was being built on the Lago de Texcoco (Texcoco Lakebed), situation that had a direct impact on 250 different species of animals and plants (Cruz, 2018).

Secondly, the cancellation of the project was used by activist and environmental organizations as a political framework, but specially by the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra (Community Front in Defense of Land, FPDT), to draw attention to the diverse and historical struggles for the land and sovereignty defense in the territories of Mexican indigenous communities. The FPDT is a farmer’s organization that, since 2001, keeps a constant opposition against of the Mexican Government to preserve the communitarian land and the Texcoco lakebed from a previous airport construction project. As a social movement, the FPDT has been the subject of a series of systematic attacks and repression; but the one that marked its trajectory was in the month of May, 2006, in the municipalities of Texcoco and Atenco: after a series of confrontations with security forces, the final balance was the deaths of two men and the detention of 217 people (47 women, 27 of whom were raped), as well as more than 30 homes raided without the corresponding search warrant, and a long list of arbitrary actions by police forces (Carrillo et al., 2009, p. 138).

The FPDT, together with Pueblos Unidos contra el Aeropuerto (Communities United Against the Airport) and the Plataforma Organizativa contra el Nuevo Aeropuerto y la Aerotrópolis (Organized Platform against the New Airport and Aerotropolis) launched the #YoPrefieroElLago campaign on September 23rd, 2018, with a broad support from Mexican activist and alternative media (Infoactivism, November 29th, 2018). From that moment on, an intense mobilization generated in Twitter and Facebook, in order to position the hashtag and spread the image and slogan for the campaign “Todos contra el NAICM” (All against the NAICM).

The rhetorical strategy focused on the environmental impacts of the project; the technical infeasibility of a construction with high maintenance costs due to its location on a lakebed; the critical water shortage historically suffered by the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico, as well as the acts of corruption that were documented as of the date of the campaign (see Figure 1). In this way, the discursive framework focused on rejecting the project, linking it to a direct disproof of the controversial public image of President Enrique Peña Nieto, who already had a history of conflict against the FPDT movement, in addition to the deep unease caused by the profound human rights crisis during his term, as well as the antagonistic symbolic configuration of the president in the face of other recent movements, such as the forced disappearance of the 43 students from the Isidro Burgos Normal School, in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero.

Thirdly, the process was involved in a series of discursive confrontations between actors from different origins, in which the position of international organizations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank, defending the technical rationality of the NAICM, and arguing the loss of the country’s reputation in front of foreign investors if the project was cancelled. Faced with this, private, public, citizen and activist media generated a communicative environment where the academia, politicians, businesspersons, airplane pilots, investors and construction workers voiced their opinions regarding the impact of the cancellation or the continuity of the project. If that were not enough, there were identified up to five contradictory technical studies regarding the operational feasibility of the presidential project (maintaining the current airport versus the two new runways at the Santa Lucía Airport), and even regarding the environmental impact reports on the Texcoco lakebed itself (ASF, 2017; Flores-Hernández, 2018; Muñúzuri, 2015; SCT, 2018).

Later, during the consultation, the discursive confrontation became even more polarized upon deciding the legal validity of the exercise, since the electoral authorities did not organize it, as the Mexican Constitution mandates for this kind of exercise of direct democracy. Instead, the Arturo Rosenblueth Foundation, academics and social organizations carried it out, staffed the voting booths and counted the votes with a wide margin of disorganization and a lack of systematization.

In this sense, the communicative process that framed the popular consultation to cancel the NAICM, and specially the strategy and results of #YoPrefieroElLago, constitute a valuable study case to identify the discursive and tactical interactions of a social movement in the complex scheme of official speeches and actors from the political, business and media opposition. All of the above, through the revision of the three types of media studied in this work: privately owned/for-profit, independent and alternative.

Methods

This article is based on a study with a quantitative, exploratory, and descriptive design. In general terms, it is a design whose emphasis is on an intent to “describe the characteristics of a group from certain variables, in a flexible interaction of elements” (Corbetta, 2007, p. 154). In this sense, the focus of the work is to answer the following research questions:

What are the coincidences and differences presented by the frequency, format characteristics and informative positioning of the content generated on the web pages and on Twitter social network, from the various actors that mobilized information during the controversy over the construction of the New México City Airport?

How did the alternative media contribute to the framing process linked to #YoPrefieroElLago in the fabric of the communicative ecology of the movement during the citizen consultation process?

To achieve this, we developed a content analysis of the information published by privately owned/for-profit, independent and alternative Mexican digital media. The content analyzed related to the controversy over the construction of the NAICM, between October 22nd and 30th, 2018; additionally, a descriptive characterization was made for the messages linked to #YoPrefieroElLago, in the context of the debate on the cancellation of the airport; these were recovered on the same dates of observation on Twitter social network.

Firstly, the selection of the sample was integrated by 12 digital media outlets, based on their characteristics of ownership and information production. Four privately owned/for-profit media, belonging to companies in the printed news industry that currently have an Internet presence as cybermedia. Four independent media, based on their work as an alternative journalistic model opposed to the for-profit model of traditional media, but that also identify themselves as companies. And four alternative -including activist, citizen, linked to Civil Society Organizations (OSC) and community- media outlets, which are defined as non-profit associations or groups (see Table 1). This sample integration was determined under non-probabilistic and for convenience criteria (Corbetta, 2007).

Table 1 Sample of selected media

| Privately owned/ for-profit media |

Citizen media | Third sector media |

| El Universal | Aristegui Noticias | Cencos |

| El Financiero | Animal Político | SubVersiones |

| Milenio | Chilango | Somos el medio |

| Excélsior | RompeViento | Desinformémonos |

Source: The author.

The research team created a database, containing all the content generated on the website of each of the selected media between October 22nd and 30th, 2018, for the delimitation of the units of analysis. As a reference, the team took four days before and two days after the publication of the results since the consultation took place between October 25th and 28th that year. In this database, the publications containing the following descriptors in their content were filtered: “NAICM”, “Aeropuerto”, “Consulta” and “Lago de Texcoco”; resulting in 905 units of analysis, distributed as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Sample of analyzed posts on web pages

| Media type | Media Name | Total number of publications |

| Privately owned/ for-profit |

El Universal | 201 |

| El Financiero | 145 | |

| Milenio | 293 | |

| Excélsior | 188 | |

| Independents | Aristegui Noticias | 10 |

| Animal Político | 25 | |

| Chilango | 7 | |

| RompeViento | 12 | |

| Alternatives | CENCOS | 7 |

| SubVersiones | 6 | |

| Somos el medio | 6 | |

| Desinformémonos | 5 | |

| Total | 905 |

Source: The author.

The team also created a database for the tweets studied, using the Node XL software, and filtering the posts on Twitter social network that contained #NAICM, #AICM, #Consulta, #Aeropuerto and #YoPrefieroElLago between October 22nd and 30th, 2018 (see Table 1). This database was limited only to the publication of tweets and retweets, eliminating mentions, reactions and follows, resulting in 8 402 units of analysis. Finally, the team introduced the information corresponding to the Node XL software that could allow the observation of the interaction dynamics from #YoPrefieroElLago in the general debate caused by the cancellation of NAICM.

Table 3 Sample of posts analyzed on Twitter

| User Type | Username | Total number of publications |

| Privately owned/ for-profit |

El Universal | 732 |

| El Financiero | 437 | |

| Milenio | 209 | |

| Excélsior | 384 | |

| Independents | Aristegui Noticias | 923 |

| Animal Político | 277 | |

| Chilango | 108 | |

| RompeViento | 799 | |

| Alternatives | CENCOS | 187 |

| SubVersiones | 365 | |

| Somos el medio | 103 | |

| Desinformémonos | 355 | |

| Other non-for-profit media and activist organizations | Accounts of social groups, activist organizations, other third sector and non-for-profit media | 1 393 |

| Public and governmental institutions | Accounts of public and governmental institutions | 275 |

| Individuals | Personal accounts | 1 855 |

| Total | 8 402 |

Source: The author.

The research team subsequently analyzed the information from both databases, based on an observation template in Excel, which allowed the systematization of the data obtained in the following categories of analysis (Table 4).

Table 4 Instrument Analysis Categories

Source: The author.

The Sentiment Analysis, carried out to detect the polarity of the expressions and positions on the two central topics, was generated through automated machine learning techniques of the SVP, or Support Vector Machine type (Alsaeedi & Khan, 2019). In this case, the research team manually segmented the messages corresponding to the two main topics evaluated (the realization of the Citizen Consultation to cancel the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed and the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed); subsequently, they applied to each database the Spanish library for Phyton’s Sentiment Analysis in order to obtain the number of messages with positive, negative or neutral polarities. As an example, the following header: “Canceling the NAICM generates mistrust, say businessmen; threaten contract lawsuits”2 (Redacción Animal Político, 2018) and the tweet “‘Land yes, planes no’, hundreds of people gather this afternoon to march against the new airport #YoPrefieroElLago”3 (Cencos, 2018) were coded as negative since they show expressions (death, threat), emoticons or feelings (distrust) whose polarity reflects negative values (-1).

To validate the results, the four members of the research team carried out cross reviews of the coding done in both databases (Krippendorff, 1990), to agree on any differences and to stablish guidelines for the criteria application on the categorization of each unit of analysis.

Finally, the database was migrated to the IBM SPSS software, which allowed the generation of descriptive statistics on trends and frequencies, as well as the tables with the crossing of variables to carry out the comparative study according to each type of media and the tweets collected.

Results and analysis

This section presents the descriptive results of each of the categories of the observation instrument, compared by type of media and by the diversity of actors that generated the tweets in the sample. In this sense, the main findings are contrasted considering the literature and other studies identified in the field of digital activism and alternative media.

Frequency of content publication: an unequal battle

The first of the categories of interest for this study refers to the proportion of contents generated by each of the actors that make up the diversity of the media studied, since some might argue that the construction of the counter-information agenda relies on the amount of information to counter a hegemonic discourse.

Table 5 shows the percentage of publications by date and by type of media generated during the week of informative confrontation regarding the construction of the NAICM. The results show that the generation of independent and alternative media content is a minimal proportion in contrast to the volume of publications from privately owned/for-profit media.

Table 5 Number of publications regarding the controversy over the construction of the NAICM

| Publication date |

Privately owned/ for-profit |

Independent | Alternative | % of total publications |

Total publications |

| 10/22/2018 | 3.3% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 4% | 35 |

| 10/23/2018 | 9.1% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 10% | 87 |

| 10/24/2018 | 8.4% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 9% | 81 |

| 10/25/2018 | 21.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 23% | 204 |

| 10/26/2018 | 12.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 13% | 117 |

| 10/27/2018 | 5.0% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 5% | 49 |

| 10/28/2018 | 6.3% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 7% | 62 |

| 10/29/2018 | 13.0% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 15% | 133 |

| 10/30/2018 | 12.8% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 15% | 137 |

| Total | 91% | 5% | 4% | 100% | 905 |

Source: The author.

The explanation for these results can be found in the general context of the study case carried out. Despite the relevance of the topic for the media agenda, on the days the analysis took place, other relevant events were also generated. Amongst them, a category 4 hurricane that devastated several towns in the Mexican Pacific on October 23rd, the day before the referendum; also, different statements and actions of the recently elected president Andrés Manuel López Obrador and an international crisis in the price of fuels complicated the production of information by the different media studied.

Moreover, Table 6 shows the number of tweets found by date and organized accordingly to the type of actor who published or retweeted information related to the consultation or the debate around the cancellation of the airport. Information trends show that, regarding the circulation of #YoPrefieroElLago, the mobilization of information by media considered independent and alternative was relevant and consistent for the duration of every day that the discursive confrontation was registered. However, it was the individual people or actors who also generated the prominence in the mobilization of information throughout the week. Official communications or pronouncements linked to public and governmental institutions kept this debate aside.

Table 6 Number and type of tweets

| Date | Individual | Privately owned/for-profit media and companies |

Independent media | Alternative media and activist organizations |

Public and governmental institutions |

Total % of tweets and retweets |

Tweets and retweets total |

| 10/22/2018 | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 4% | 372 |

| 10/23/2018 | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 0% | 11% | 934 |

| 10/24/2018 | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 0% | 13% | 1 074 |

| 10/25/2018 | 4% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 1% | 16% | 1 378 |

| 10/26/2018 | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 0% | 11% | 923 |

| 10/27/2018 | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 0% | 12% | 1 043 |

| 10/28/2018 | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 0% | 11% | 902 |

| 10/29/2018 | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 0% | 13% | 1 087 |

| 10/30/2018 | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 8% | 689 |

| Total | 22% | 21% | 25% | 29% | 3% | 100% | 8 402 |

Source: The author.

This trend indicates that this are self-referential networks, with well-articulated communities, that could sustain the continuous circulation of information, with more intensity on the first day of the consultation (October 25th) and, subsequently, increasing on the day the results were published (October 29th).

In the different studies that have characterized alternative media, it has been found that this media is generally conformed by small work teams (Kaplún, 2019), with high levels of volunteering (Monje & Rivero, 2018). These teams have the direct incidence in the production volume of self-produced content, which keeps placing them in a position of marginalization compared with the independent or the privately owned/for-profit media that have an organizational structure to sustain the continuous production of information. Therefore, the strengths in this type of media are their networks and the articulation with diverse actors (Barranquero & Candón, 2021), specifically, with users of the digital social networks, that constitute the most significant operational part for the mobilization of symbolic resources for this type of media. In this sense, the construction of the counter-information agenda could have more impact in the field of interaction inside the digital social networks than merely the production of news or information in the web movement’s sites.

A diversity of actors without much diversity in format

The second category addressed in the analysis refers to the format of the information spread during the controversy, since the potentiality of the audiovisual and hypertextual content could contribute to the emotional dimension of the framing and in the construction of the common appellative references from the direct experience of the movement´s participants (Castells, 2012; Sierra, 2020).

In this instance, the organizational platform that bonds together all the actors with the slogan “All against the NAICM”, generated some specific materials to disseminate on the Internet. These materials integrated different visual elements with a high symbolic power: a rejection to the airport project associated with the disapproval of the president Enrique Peña Nieto; icons of the FPDT and the Ejército Zapatista (Zapatista Army, EZLN) resistance; and a strong integrative emphasis on the different social movements that at the time had a strong presence in the public sphere, due to the severe human rights crisis in the country (see Figure 2).

Source: Plataforma Organizativa contra el Nuevo Aeropuerto y la Aerotrópolis (2018).

Figure 2 Oficial poster of #YoPrefieroElLago

This platform made available pictures, infographics, a “letter from the lake” that could be answered or interacted with, a documentary video, materials to print and distribute, as well as public and virtual events.4 However, the findings related to the format of the contents disseminated on both the websites and the social networks, show that, despite all the diversity of resources, the bulk of the information generated focused in the images and text related to the construction of the NAICM.

In the case for each type of media publication, Table 7 shows that multimedia and hypertextual contents are scarce, being the bulk of information text with accompanying images. Even so, the infographics generated by the organizative platform itself were not widely spread on the web pages of the different types of media as a companion resource to the journalistic information of their websites.

Table 7 Format of the contents published in the Media

| Media type | Content format | ||||||

| Video | Audio | Text | Image | Multimedia | Infographic | Hypertext | |

| For-profit Media (n=827) |

27 | 0 | 821 | 208 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Independent media (n=46) |

11 | 0 | 32 | 30 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Alternative media (n=32) |

13 | 1 | 30 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total % | 4% | 0% | 73% | 20% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Total | 51 | 1 | 883 | 247 | 10 | 4 | 10 |

Source: The author.

Note: The results do not add up to a 100% since a single analysis unit could contain more than one format characteristic.

Regarding the information circulating on Twitter, Table 8 shows that the preponderant materials were also text and images. Moreover, the graphic resources of the social movement organizational platform had, in this space, a more significant relevance, being key the infographics about the environmental impact of the construction work and the images derived from the fight of the FPDT.

Table 8 Format of the information circulating on Twitter

| Actor type | Video | Audio | Text | Image | Infographic |

| Individual (n=1 855) | 37 | 3 | 1 838 | 960 | 494 |

| and enterprises (n=1 762) | 63 | 0 | 1 752 | 1 645 | 0 |

| Independent media (n=2 107) | 17 | 1 | 2 107 | 2 103 | 405 |

| Alternative media and activist organizations (n= 2 403) |

36 | 2 | 2 403 | 867 | 673 |

| Public and governmental institutions (n=275) |

0 | 0 | 275 | 275 | 0 |

| Total % | 1.8% | 0.1% | 99.7% | 69.6% | 18.7% |

| Total | 153 | 6 | 8 375 | 5 850 | 1 572 |

Source: The author.

Note: The results do not add up to a 100% since a single analysis unit could contain more than one format characteristic.

These findings match the ones on other studies that support the importance of digital social networks in the propagation of contents that add to the connectivity logic of the social movement (Barranquero & Meda, 2015; Candón et al., 2017; Lim, 2018). Even more than in the field of the media informative agenda, it is in the digital interaction that the actors have the opportunity to place the counter-informative elements. In this case, the alternative media, while showed a low density of self-produced information on the topic, evidenced a relevant participation by mobilizing the resources generated for the movement platform.

The opposing positions

Finally, one of the most substantial categories to show the discursive plot of the study case was the positions of the several types of actors in front of the major subject debated during the week of the citizen consultation. Firstly, which polarity had the opinions about the realization of the participative democracy exercise since it had no precedent in the country. Secondly, how they evaluated the construction of the Airport at the Texcoco lakebed.

In this case, the results of the evaluation on the positioning of publications in web pages, for each type of media, show that privately owned/for-profit media were the ones that relied more heavily on the transmission of messages with negative feelings towards the consultation. However, most of the published information was on a neutral tone since it did not correspond to the specific topic or adjectivized the consultation. There were also positive feelings identified, as part of the journalistic exercise to voice different opinions. The independent media type was the one that, proportionally, presented a more balanced mixture in the postures. Meanwhile, the alternative media presented an evident tendency to favor the citizen participation exercise (see Table 9), confirming that this type of media present a politically situated communication. In the context of the study case referred, it was identified that their contents were not looking to generate a diversity in the analysis or the contrast of positions, as in the case of investigative or everyday descriptive journalism, but rather propagate a political position in relation to the event.

Table 9 Positioning regarding the consultation, according to media type

| Positioning regarding the realization of the Citizen Consultation to cancel the construction of the NAICM at the Texcoco lakebed |

|||

| Media type | Negative | Neutral | Positive |

| Privately owned/for-profit media (n=827) |

313 | 363 | 151 |

| Independent media (n= 46) | 15 | 21 | 10 |

| Alternative media (n=32) | 5 | 13 | 14 |

| Total % | 36.8% | 46.9% | 19.3% |

| Total | 333 | 397 | 175 |

Source: The author.

On the other side, upon the observation of the information dynamics in the digital social networks through the Sentiment Analysis, it was possible to observe the use of a different kind of discursive construction in the digital context. On Twitter, we found that the alternative media, along with activist collectives, presented comments with a clearly positive referenciality towards the participation exercise; however, in the deliberation related to publications of individuals is where the major tendencies to confront existed, according to the identified feelings. The privately owned/for-profit media showed a more identifiable tendency of negative polarities towards the cancelation of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed, while the independent media showed a more balanced position contrast, with different approaches on the subject. In the case of the public and governmental institutions, it is worth mentioning that no publication on the subject was found.

Lastly, regarding the positioning towards the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed, it is observable that the information obtained from for-profit media showed an evident tendency for positive messages. The independent media showed more publications of a neutral tone. And the alternative media were more inclined towards a negative position regarding the construction of the NAICM, due to the affectations for the lakebed (Table 11).

Table 10 Positioning in Twitter regarding the consultation

| Positioning regarding the implementation of the Citizen Consultation to cancel the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed |

|||

| Actor type | Negative | Neutral | Positive |

| Individuals (n=1 855) | 541 | 835 | 479 |

| Privately owned/for-profit media and companies (n=1 762) |

435 | 1 073 | 254 |

| Independent media (n=2 107) |

443 | 1 119 | 545 |

| Alternative media and activist organizations (n=2 403) |

524 | 1 052 | 827 |

| Public and governmental institutions (n=275) |

0 | 275 | 0 |

| Total % | 23.1% | 51.8% | 25.1% |

| Total | 1 943 | 4 354 | 2 105 |

Source: The author.

Table 11 Positioning regarding the construction of the NAICM, by media type

| Media type | Positioning regarding the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed |

||

| Negative | Neutral | Positive | |

| For-profit media (n=827) | 88 | 424 | 315 |

| Independent media (n=46) | 9 | 21 | 16 |

| Alternative media (n=32) | 18 | 12 | 2 |

| Total % | 12.7% | 50.5% | 36.8% |

| Total | 115 | 457 | 333 |

Source: The author.

On the Twitter social network messages, the trend is also similar. Those who moved the greatest quantity of information were the independent and alternative media along with activist organizations; in this instance, only the last showed a preference for negative contents regarding the project. However, it is again noticeable the relevance of the presence of individuals and privately owned/for-profit media, which made the positive information related to the airport project part of Mexico’s national tendencies on these networks.

Table 12 Positioning regarding the construction of NAICM on Twitter

| Positioning regarding the construction of the NAICM on the Texcoco lakebed |

|||

| Actor type | Negative | Neutral | Positive |

| Individuals (n=1 855) | 429 | 947 | 479 |

| Privately owned/for-profit media and companies (n=1 762) |

310 | 1 003 | 449 |

| Independent media (n=2 107) |

206 | 1 686 | 215 |

| Alternative media and activist organizations (n= 2 403) |

865 | 1 072 | 106 |

| Public and governmental institutions (n=275) |

0 | 275 | 0 |

| Total % | 22.5% | 62.0% | 15.5% |

| Total | 1 810 | 4 983 | 1 249 |

Source: The author.

In these results is possible to identify that the communication of the alternative media is transmitted from a politically situated referent. This contradicts the canons of traditional journalism, which present a diversity of positions that can disconcert the reader since they oppose each other. In an informative ecosystem filled with actors posting positive and negative messages, having referents whose position is straightforward can be considered a contribution to reduce the uncertainty generated by the large amount of information produced around the controversy.

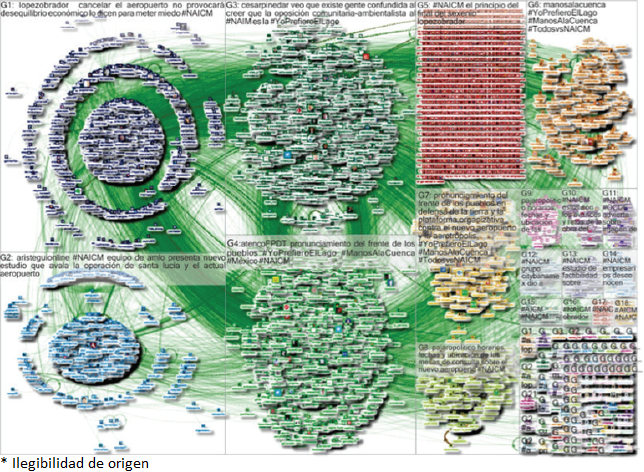

Lastly, Figure 3 shows a network of 8 402 Twitter users whose tweets contained the #NAICM, obtained on October 30th, 2018, at 23:00 hours of Mexico’s Central Standard Time. In this case, stands out that the actors with the greatest relevance on the issue are linked to the following users: the account of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (@lopezobrador_); Aristegui Noticias, one of the independent media studied (@AristeguiOnline); an activist (@cesarpinedar), and the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra de Atenco (@AtencoFPDT)

Source: The author.

Note: This is a directed graph. The graph vertices were grouped in conglomerates using the Clauset-Newman-Moore conglomerates algorithm. The graph was designed using the Harel-Koren Fast Multiscale layout algorithm.

Figure 3 Graph showing interactions in Twitter social network

This can add to the description of the analysis trends previously shown and confirms that the configuration of the communicative ecology of a social movement has concrete opportunities to position its discursive frameworks through the alignment of actors that agree with these concrete messages. For this reason, the convergence of interests with the discourse of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the context of the intense debate managed to be the circumstantial space for the FPDT to link its slogan #YoPrefieroElLago.

Discussion

The result of the consultation, published on October 29th, registered the participation of 1 067 859 people (an important result but one that represented less than 1% of the Mexicans over 18 years of age in the electoral register). The vote count showed that only 29% were in favor of continuing with the NAICM project and 69.9% voted to build two runways at a military air base in Santa Lucía, State of Mexico. These results were a great victory for the FPDT and the activist platform that promoted the #YoPrefieroElLago campaign; however, the struggle of these actors continues to develop around the severe water crisis in the Valley of Mexico basin and the defense of these communities’ territory.

Despite this concrete result, it is still difficult to link the communicative dynamics of the social movement with the final scope of the political transformation that the preservation of Lake Texcoco entailed through this participatory exercise. The result achieved was the product of the alignment of other actors and political forces, who saw in the cancellation of the airport the opportunity to present a position expressing their rejection of the regime of President Enrique Peña Nieto.

What we can outline as specific contributions from the research carried out are some features of the dynamics of actions and interactions of alternative media in the communicative ecosystem of a social movement. Firstly, the correct use of the slogan “All against the NAICM”, which made possible the articulation of the different actors and movements dissatisfied with the actions of the federal government, the corruption processes or vindicate struggles for the defense of the land and territory of several communities throughout the country.

Secondly, it is verified the performativity of support for social causes and struggles through the mobilization of resources in their social networks, this being one of the main strengths of this type of media. The counter-hegemonic nature of the information production of the alternative media links them with specific political views, which positions them in front of a cause or event from the context of the actors participating in the movement. This is far from the classic strategy of journalistic analysis, which looks to contrast perspectives so the audience can form a rational judgment, but it becomes a key reference for people in a scenario overloaded with contradictory information, as was the case of study. In this sense, the alternative media in Mexico could contribute to build a plural media landscape, having a greater capacity for social interpellation and reach.

As for the frequency of production of their own content, there are limitations that place them at a disadvantaged point compared to other types of media with larger or more specialized production teams. Hence, the identified strategy of circulating information from their contact networks is key to observe the timely participation of these media. In this sense, the idea of integrative hybridization of media practices and activism developed by various authors is verified (Chadwick, 2013; Mattoni, 2017; Treré, 2020), since the logics of the traditional media system are added to the strategies of information circulation in social networks.

Undoubtedly, this type of integrative approach has research challenges such as developing elements of greater depth in the contents, probably from a qualitative context or from the visibility of its flows, with a mathematical approach from graph theory, but as a whole, the proposed work allows an exploration of the specific role of alternative media in a process of discursive framing, through their participation in several digital scenarios and in a referential position compared to other actors.

REFERENCES

Alsaeedi, A. & Khan, M. (2019). A Study on Sentiment Analysis Techniques of Twitter Data. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 10(2), 361-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0100248 [ Links ]

Auditoría Superior de la Federación-ASF. (2017). Impacto Ambiental del Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de la Ciudad de México. https://www.asf.gob.mx/Trans/Informes/IR2017c/Documentos/Auditorias/2017_1682_B.pdf [ Links ]

Auditoría Superior de la Federación-ASF. (2021). Costo del esquema de financiamiento, construcción y terminación anticipada de contratos del NAICM. https://www.asf.gob.mx/Publication/5210_NAICM [ Links ]

Barranquero, A. & Candón, J. (2021). La sostenibilidad del Tercer Sector de la Comunicación en España. Diseño y aplicación de un modelo de análisis al estudio de caso de El Salto y OMC Radio. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 137, 1-20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5209/reve.71863 [ Links ]

Barranquero, A. & Meda, M. (2015). Los medios comunitarios y alternativos en el ciclo de protestas ciudadanas del 15M. Athenea Digital, 15(1), 139-170. https://raco.cat/index.php/Athenea/article/view/292078 [ Links ]

Candón, J. (2013). Toma la calle, toma las redes. El movimiento #15M en Internet. Atrapasueños Editorial. [ Links ]

Candón, J. & Benítez, L. (2016). Activismo digital y nuevos modos de ciudadanía: Una mirada global. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Candón, J., Vilar, G. & Rosique Cedillo, G. (2017). Juventud, medios comunitarios y transición digital en el contexto español. En V. Barragán & I. Terceros (Eds.), Radios, redes e Internet para la transformación social (pp. 251-277). Ediciones Ciespal. [ Links ]

Carrillo, B. E., Zapata, E. & Vázquez, V. (2009). Violencia de género hacia mujeres del Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra. Política y Cultura, 32, 127-147. https://polcul.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/polcul/article/view/1098 [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2012). Redes de indignación y esperanza. Los movimientos sociales en la era de Internet. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Cencos [@cencos]. (2018, 25 de octubre). Con el grito de “Tierra sí, aviones no” cientos de personas se reúnen esta tarde para marchar contra el nuevo aeropuerto. #YoPrefieroElLago [Tuit]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/cencos/status/1055572398324408321 [ Links ]

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199759477.001.0001 [ Links ]

Corbetta, P. (2007). Metodología y técnicas de investigación social. McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Cruz, E. (2018, 24 de octubre). Equipo de AMLO presenta nuevo estudio que avala la operación de Santa Lucía y el actual aeropuerto. Animal Político. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/10/estudio-santa-lucia-nuevo-aeropuerto/ [ Links ]

Flores-Hernández, J. (2018). Evidencias técnicas, ambientales y sociales del impacto negativo del proyecto de desarrrollo del NAICM y su aerotrópolis asociada en la vida y derechos humanos de los habitantes de la Cuenca de México. https://bit.ly/3I2ej0Z [ Links ]

Forbes Staff. (2018, 27 de septiembre). #YoPrefieroElLago, la campaña que busca frenar el aeropuerto en Texcoco. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com.mx/yoprefieroellago-la-campana-que-busca-frenar-el-aeropuerto-en-texcoco/ [ Links ]

Giraldo-Dávila, A. F. & Maya-Franco, C. M. (2016). Models of communicative ecology: An analysis of the communication ecosystem. Palabra Clave, 19(3), 746-768. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2016.19.3.4 [ Links ]

Gómez, R. (2018). The Mexican Third Sector of the Media: The Long Run to Democratise the Mexican Communication System. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 16(1), 332-352. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i1.945 [ Links ]

Infoactivismo. (2018). El caso #YoPrefieroElLago Algunos apuntes infoactivistas sobre la estrategia y tácticas. https://infoactivismo.org/tacticas-de-la-campana-yoprefieroellago/ [ Links ]

Kaplún, G. (2019). ¿Vivir o sobrevivir? Sostenibilidad de las alternativas mediáticas en Uruguay. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. [ Links ]

Kidd, D. & McIntosh, K. (2016). Social Media and Social Movements. Sociology Compass, 10(9), 785-794. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12399 [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. (1990). Metodología de análisis de contenido. Teoría y práctica. Paidós. [ Links ]

Lim, M. (2018). Roots, Routes, and Routers: Communications and Media of Contemporary Social Movements. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 20(2), 92-136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1522637918770419 [ Links ]

Martínez-Mendoza, S. & Ramos, D. (2021). Medios digitales e independientes en búsqueda de financiamiento: el caso Tejiendo Redes. En J. A. Hidalgo-Toledo (Ed.), Transformaciones mediáticas y comunicacionales en la era posdigital (pp. 27-48). RIA editorial. [ Links ]

Mattoni, A. (2017). A situated understanding of digital technologies in social movements. Media ecology and media practice approaches. Social Movement Studies, 16(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1311250 [ Links ]

Millaleo, S. & Velasco, P. (2013). Activismo Digital en Chile. Repertorio de contención e iniciativas ciudadanas. Fundación Democracia y Desarrollo. [ Links ]

Monje, D. & Rivero, E. (2018). Televisión cooperativa y comunitaria. Diagnóstico, análisis y estrategias para el sector no lucrativo en el contexto convergente. Convergencia Cooperativa. [ Links ]

Muñúzuri, S. (2015). Los impactos ambientales de la construcción del NAICM [Ponencia]. El Nuevo Aeropuerto de la Ciudad de México a debate. Senado de la República. https://www.senado.gob.mx/comisiones/cambio_climatico/reu/docs/presentacion3_150415.pdf [ Links ]

Plataforma Organizativa contra el Nuevo Aeropuerto y la Aerotrópolis. (2018). Comparte #YoPrefiero. http://yoprefieroellago.org/comparte/ [ Links ]

Ramos-Martín, J., Morais, S. & Barranquero, A. (2018). Las redes de Comunicación Alternativa y Ciudadana en España. Potencialidades, dificultades y retos. OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 13(1), 121-148. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2018.13.1.05 [ Links ]

Redacción Animal Político. (2018, 29 de octubre). Cancelar el NAIM genera desconfianza, dicen empresarios; amenazan con demandas por contratos. Animal Político. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/10/reacciones-consulta-naim-santa-lucia/ [ Links ]

Scolari, C. (2015). Ecología de los medios. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes-SCT. (2016). Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de la Ciudad de México. Informe Anual 2016. http://www.gacm.gob.mx/doc/pdf/NAICM_IA_pages.pdf [ Links ]

Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes-SCT. (2018). Aspectos ambientales del Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de México. http://aeropuerto.gacm.mx/2018/aeropuerto/doc/transicion/mesas/GACM_SEMARNAT_Medio_Ambiente.pdf [ Links ]

Sierra, F. (2020). Marxismo y comunicación: Teoría crítica de la mediación social. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Tilly, C. & Wood, L. (2010). Los movimientos sociales, 1768-2008. Desde sus orígenes a Facebook. Editorial Crítica S. L. [ Links ]

Treré, E. (2020). Activismo Mediático Híbrido. Ecologías, imaginarios, algoritmos. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. [ Links ]

Trillos, J. J. & Soto-Molina, J. (2018). El poder de los medios masivos tradicionales y las plataformas digitales en el activismo político. Encuentros, 16(2), 62-78. http://ojs.uac.edu.co/index.php/encuentros/article/view/1440 [ Links ]

van Dijck, J., Poell, T. & De Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society. Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190889760.001.0001 [ Links ]

Van Laer, J. & Van Aelst, P. (2011). Cyber-protest and civil society: The Internet and action repertoires in social movements. En Y. Jewkes & Y. Majid (Eds.), Handbook of Internet Crime (pp. 230-254). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781843929338 [ Links ]

3“‘Tierra sí, aviones no’, cientos de personas se reúnen esta tarde para marchar contra el nuevo aeropuerto. #YoPrefieroElLago”.

4All the resources are available in the portal http://yoprefieroellago.org/

How to cite:

Lemus Pool, M. C. (2022). Communicative ecology of the #YoPrefieroElLago movement: an approach from private, independent, and alternative media. Comunicación y Sociedad, e8188. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8188

Received: June 25, 2021; Accepted: October 08, 2021; Published: March 23, 2022

texto en

texto en