Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.17 Guadalajara 2020 Epub 30-Ago-2021

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7365

General theme

Video games as critical ludofictional worlds: the case of the Spanish political crisis in mobile digital entertainment (2008-2015)

1 Universidad Pompeu Fabra, España. aplanells@tecnocampus.cat

The purpose of this research is to analyze the critical-discursive capacity of contemporary persuasive video games. The ten most popular titles for mobile phones whose central theme is the crisis in Spain from 2008 to 2015 have been analyzed using a methodology based on the theory of possible worlds and procedural rhetoric. The results show how parody is used as the main ludic catalyst in the treatment of socially exposed events, which are, in turn, the elements that make up the mechanics and dynamics of the gaming experience.

Keywords: Videogames; crisis; persuasion; possible worlds; ludofictional worlds

La presente investigación tiene por objetivo analizar la capacidad crítico-discursiva del videojuego persuasivo contemporáneo. Se han analizado los diez títulos para móvil más populares cuya temática central es la crisis en España desde 2008 a 2015, mediante una metodología basada en la teoría de los mundos posibles y la retórica procedimental. Los resultados muestran cómo la parodia se usa como principal catalizador lúdico en el tratamiento de los hechos denunciados a nivel social, que son, a su vez, los elementos que conforman las mecánicas y dinámicas de la experiencia de juego.

Palabras clave: Videojuegos; crisis; persuasión; mundos posibles; mundos ludoficcionales

Introduction

From the end of 2007, an emerging international context of economic crisis began to take its toll on many countries around the world until, in September 2008, the bankruptcy of the investment firm Lehman Brothers officially marked the beginning of the global recession. Along with this international situation, Spain faced its internal financial problems, mainly an economic bubble centered on real estate speculation and a significant increase in unemployment. Furthermore, disenchantment with a democratic model that was being questioned by corruption, criticism of its institutions, and images of evictions in the media generated a relevant social crisis and the rise of certain citizen movements.

Within this economic and social framework, both Spain and Europe have seen how video games have been consolidated as a profitable entertainment industry, at least for consumption. Along with the new generation of consoles (Playstation 4, Xbox One and Switch) and the second life of the Pc thanks to digital gaming platforms such as Steam, mobile games have become more popular thanks to the huge number of smartphones (especially with the Android operating system, although iOS is still behind) and tablets. However, can we analyze games as a medium capable of generating its discursive system, thus overcoming the classic (and simplistic) legitimization through its economic potential? Does this interactive medium, considered since 2009 as a cultural industry, have a real potential not only as a ludic activity but also as a catalyst for economic and social problems?

In this research, we analyze the economic and social problems of the Spanish crisis in the 2008-2015 period, from the perspective of those video games that have focused on this issue. From the social and media impact of digital gaming, it is key to understand what link can be established, on the one hand, between the phenomenon of the Spanish crisis and its representation in one of the most popular mass media in the country. On the other hand, video games are an interactive medium whose potential lies in the process of ludic simulation, so it is relevant to understand precisely how Spanish games have tried to (re)build Spanish society and politics from game mechanics and user experience orientation. In this sense, we have focused on the proposals that have appeared in mobile media, specifically in Android, the most widespread operating system in our country. This support has been chosen for two reasons. Firstly, mobile technology has allowed for low production costs and its digital distribution has enabled more direct access to its potential audience, so it is reasonable that video games with a more critical discourse (and, in turn, with less industrial support) have found in mobile phones and tablets their natural development space. Secondly, it should be considered that Spain is not a country with a relevant or established industrial network, so that the discursive capacity of the creators of large video games (the so-called Triple-A) on consoles and computers continues to be somewhat anecdotal.

For this reason, we will first establish the basic principles of the theory of argumentation centered on the concept of possible world (Capdevila, 2004a; Dolezel, 1999; Eco, 1981; Pericot, 1997) and then we will contrast it with its reformulation in video games (Ryan, 1992) and its conformation as a ludofictional world (Planells de la Maza, 2015a). The last part of the research establishes a video game sample and the selection criteria, its analysis, and main results.

Theory of argumentation and possible worlds

Rhetoric, or the art of persuasion, has had a mixed fortune depending on the historical time in which we focus. In ancient Greece, argumentation and the ability to influence the polis was understood to be a central element in the survival of the community, especially in times of internal crisis and external military conflict. In this way, rhetoric was erected as a rational process of evaluating reality and reorienting the general attitudes of the community.

However, rhetoric will fluctuate between the ages of prosperity and decadence depending on its role in society. In medieval contexts and in subsequent non-democratic forms of government, persuasion is understood as a system of mass control in the hands of an elite who have both the technical resources for communication and the intellectual knowledge to produce powerful discourses. In these cases, the rational Greek argumentation becomes a simple trick in the hands of a few. On the other hand, in democratic political models, rhetoric has emerged as an admissible tool of political combat, both in daily life (debates in parliaments, political participation in the media) and in events of relevance to these political systems, such as general elections or referendum processes.

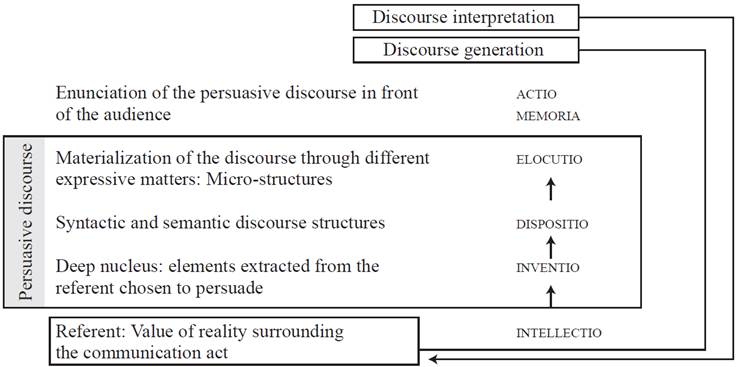

In this framework of re-evaluation of the political debate as the basis for democracy, it is worth adding the contribution that cinema and television have been making since the 20th century. Rhetoric is no longer limited to a mere dialectical construction based on words, but now images, non-verbal communication, and the speaker’s public image are also very important. As established by Capdevila (2004 a, p. 18), in the mid-1950s the Belgian philosopher Chaïm Perelman (1994) reformulated the classic postulates of the argumentative model of rhetoric in connection with a specific audience to which the speaker should be addressed. Capdevila (2004a, pp. 37-40) synthesizes Perelman’s work in three phases: the rhetorical ideation (intellectio), the construction of the discourse (inventio, dispositio, and elocutio) and its enunciation (memory and actio).

The intellectio or ideation phase of the rhetorical model implies understanding the general postulates of the argumentative framework we are going to use. Thus, here we define, among other things, the target audience of the persuasive story, the medium to be used (written text, television...), the essential content of the message, or the accessory tools to be used. Once the general framework of the argumentative discourse is established, the next phase is to design its final form. The first step, inventio, involves consulting our referential world (our empirical, social, ideological, economic, and/or cultural reality) to extract general elements. This step is key in two ways. Firstly, it allows us to connect with our audience thanks to common and understandable elements, the socalled “encyclopedia” by Eco (1981). Secondly, it allows us to shape a specific possible world. We understand by a possible world, in the words of Pericot (1997), “a narrative world with a cultural structure that, although not effective, is ‘true’ to the extent that it is formed by a set of individuals endowed with properties and events that are judged to be possible and coherent” (p. 161). Thus, this possible world is, in reality, a set of possible states without real existence, unlimited, diverse, autonomous, and significant in itself (Dolezel, 1999, pp. 35-47).

The next step in the configuration of persuasive discourse is dispositio, that is, the creation of the structure that establishes the general ideas of the possible world in a specific order that seeks to strengthen the argumentative process from the speaker’s perspective. This rhetorical framework is translated, in the process of elocution, into an aesthetic discourse, embellished and, at the same time, profoundly significant. In this sense, elocutio does not only involve a logical or narrative arrangement, but also a specific textual and audiovisual elaboration that directly appeals to the audience in an emotional and creative sense. Thus, elocutio is not only a coherent construct for the possible world but also (or especially) an appeal to the interest of the audience.

Finally, the material enunciation of the persuasive discourse in front of the audience is carried out in two phases: memory and activation. Memory implies the mental registration by the speaker of the final form of exposition of the discourse, while actio implies the effective display of the story in the eyes of the final audience.

Methodology: Persuasion and video games

Since the 1980s, video games have experienced a meteoric rise, both industrially and culturally. While the first arcade games and home consoles generated a model for children’s and teenagers’ entertainment with functional graphics and simple narratives, today video games are a medium capable of much more. Together with the large-scale ludic blockbusters (known as “Triple-A”), video games have reached new audiences (Salen, 2008), or more diversified user profiles such as casual and hardcore (Juul, 2010). Also, they are increasingly being used in sectors outside of digital entertainment, such as education (Lacasa, 2011; Squire, 2011) or companies through the so-called serious games (Gómez, 2014).

One of the most interesting perspectives with the greatest potential is the persuasive dimension of the video game’s interactive discourse. Bogost (2007) defined this new form of discourse as “procedural rhetoric”, an “interpretative practice of arguments through processes” (p. 28) that can be seen in politically oriented video games, such as those generated by Molleindustria, in advergaming or advertising games, and in recent newsgames, titles that aim to inform while providing a ludic experience (Gómez & Navarro, 2013).

The procedural rhetoric is based on an essential premise: the video game is an interactive medium and it is through user-system interaction that the underlying argument emerges (Ryan, 1992). For this reason, while in classical rhetoric the audience reaches the deep macro-structure of the intellectio through the reception and interpretation of a closed discourse (actio), in the video games a performative activity of the user is required to reach the rhetorical substrate. In this way, we move from possible worlds of fiction that address a listener in a pre-established way to the so-called “ludofictional worlds” (Planells de la Maza, 2015a, 2015b, 2017), ludic and fictional spaces that display a persuasive discourse of procedural rhetoric through the direct interaction of the user.

This necessary user activity leads to an important modification in the persuasive structure of Perelman’s model. While the deep level can be maintained, both the conformation of discourse and its enunciation will be modified. Thus, while in traditional rhetoric the intellectio seeks the audience profile, in any ludofictional world the intellectio also seeks the most appropriate type of player (socio-demographic, casual/hardcore profile), the gaming platform (smartphone, tablet, Pc, handheld or home console) and its possibilities and limitations in the user interface.

The level of conformation (which here we call “configuration” or implementation of the gameplay) is based on the MDA model (mechanics, dynamics, aesthetics) proposed by Hunicke, Leblanc & Robert (2004). In this system, the creation of the ludic world as a specific dimension of an intellectio goes through the phases or layers of the pre-written mechanics, dynamics, and experiences (which Hunicke et al. (2004) call “aesthetics” but which for reasons of expository clarity we will not translate literally).

Table 1 Comparison between classic and ludic persuasive model

| Persuasive possible world | Persuasive ludic world | ||

| Ideation | Intellectio | Prefiguration (Game Design) |

Intellectio |

| Conformation | Inventio Dispositio Elocutio |

Configuration (Gameplay) |

Mechanics Dynamics Experiences |

| Enunciation | Memoria Actio |

Refiguration (Play) |

Action/state change/ feedback |

Source: The author.

The game mechanics phase involves extracting from a specific reference world (an empirical reality, a literary work, a fictional world that has been invented) a set of rules of the game that, in line with the fictional dimension, have a particular persuasive meaning. In this way, the game mechanics phase is not only inspired by the intellectio, but also seeks an internal coherence to efficiently develop the framework of the procedural rhetoric. The next step is to integrate the mechanics and check the system’s behavior in realtime. While the mechanics are the pieces of the game engine, the dynamics are the links that bring the pieces together and test them when the engine is turned on. In this way, in contrast to the static and individuality of the rules, the dynamics seek to cohere the model in motion to check its potential flaws. In other words, the dynamics phase puts the game into action and asks whether it manages to convey the argumentative model envisioned by the designer.

Once the dynamics phase is over, it is important to connect the persuasive perception of the system with a given ludic experience. If our game wants to persuade the player of the benefits of recycling, what kind of experience will it provide? Is it going to be a quick game (action game), tactical (strategy), or narrative exploration (adventure)? As can be seen, the dynamics phase does not necessarily prescribe an experience, but rather a systemic model that gives an account of a central discourse and then adapts it to a particular kind of game. However, the whole dimension of conformation of the ludofictional world follows the same interrelation principles of classical rhetoric. In other words, we can divide and categorize on a theoretical level the main differences between mechanics (inventio), dynamics (dispositio) and experience (elocutio) without prejudice to understanding that at the end they must all collaborate, often simultaneously and in parallel (Capdevila, 2004 a, pp. 32-35).

The final phase, which matches the enunciation of the classic model, is the refiguration or play phase in which the end-user will interact with the system. In video games, the action system is usually linked to a virtual avatar or a specific graphic interface that allows the player to perform a set of specific or determinable acts. These actions have an impact on the gaming world and trigger a set of results or feedbacks that are communicated back to the player, usually through the interface. This is the case, for example, in combat. The player can use one of the weapons provided by the game against an enemy (action) and depending on their skill, they can modify the game world in a specific way: the enemy is not damaged, is injured or dies directly. This state change caused by the user’s action will be communicated back through a feedback process. Thus, a spectacular explosion may symbolize the death of the enemy, an indicator above his head may point out that he has been wounded, or the hero’s stumble may mark a failure in the attack.

The ludofictional worlds of the Spanish crisis: sample analysis

Based on this methodological framework of ludofictional worlds, we are going to analyze how Spanish video games have tried to transmit the problems of the crisis using their ludic language. To this end, we have chosen ten video games for Android published between 2008 and 2015 that reflect the main issues of this period on a thematic level. The selection has followed a double criterion: on the one hand, different searches have been carried out in Google Play from a battery of keywords that defined the political actors, the most relevant topics, and the most popular characters. The main words were “crisis”, “crisis Spain”, “corruption”, “PP”, “Psoe”, “Ciudadanos”, “Podemos”, “Bárcenas”, “Pujol” or “Rajoy”, among others. The results obtained were filtered by the number of downloads and opinions. Google Play does not give exact figures, but it does give ranges of application installations per device, so it was decided to analyze those titles that had been installed most often and, equally, those that had obtained the most feedback in the platform ratings. Finally, the titles chosen in order of publication were Mariano Ninja (JanduSoft, 2012), Safari King (Jotandroid, 2012), Chorizos de España (Ravalmatic, 2013), Darsenas, Tesorero Corrupto (4d3/Animation Studio, 2013), Marea Verde (3brothersinlaw, 2013), Alcalde Corrupto Clicker (Meigalabs, 2015), Azota la Casta! (CilupiaStudio, 2015), Elecciones 2015 (Pixélika webs&apps, 2015), Troll en Campaña (Miguel Cobos Sanchez, 2015), and Spanish Fighters III (MindFunk, 2015).

Results and analysis

The temporary anchorage of the crisis milestones as ludofictional worlds

All of the video games analyzed start, in one way or another, from a local Spanish reference world to generate their ludic world. Specifically, the four most relevant frameworks are the news events that had a relevant impact on public opinion, the logic of the crisis in the Spanish cultural context, the relevant political figures, and the electoral model. In the first case, the game Safari King creates its world from the incident that King Juan Carlos starred in when he broke his hip after an elephant hunt in Botswana. In the same line, the news about corruption linked to Luis Bárcenas, former treasurer of the Partido Popular (Popular Party) inspires the intellect and the conformation of the ludic space of the titles Chorizos de España and Darsenas, Tesorero Corrupto. In the case of the crisis logics, proposals such as Marea Verde build their persuasive model precisely as a criticism to the cuts in primary and secondary education, while Alcalde Corrupto identifies the illicit activities in the contracting of local urban development projects as the basic foundation of the recession and the fall of the economic-social model.

Regarding the intellectio focused on the temporal anchorage of the political class, the titles Mariano Ninja and Spanish Fighters III develop two different frameworks with different protagonists. In the first case, we control the president of government and the ludic proposal synthesizes in a single game the period of exercise of the Spanish Executive. Thus, we must “cut” (as if we were ninjas) the negative elements of our politics as Mariano Rajoy, while we must avoid affecting the de facto powers. While Mariano Ninja is a combo game, Spanish Fighters III follows the logic of Street Fighter style fighting games. Here we take Pablo Iglesias to a specific moment: his performance in La Secta Noche (in a parodic allusion to the tv show La Sexta Noche) and his conflict with Paco Marhuenda, director of the newspaper La Razón. The game also includes another fight with Albert Rivera.

The last temporary anchorage is produced with the criticism of the Spanish electoral model. In this case, games like Elecciones 2015 or Troll en Campaña use the time frame of the general elections of 2015 to criticize the homogenization of the political parties and try to create awareness about the potential that socialbased activism has to control the correct behavior of the political class. Thus, in Elecciones 2015 we can discard the votes that do not interest us, although the game puts them all on an equal level. In this way, the persuasive model urges us to execute the same action and to define ourselves politically, in a critique of the basic equality of all politicians, and which are only differentiated by the party’s corporate logo. In contrast, Troll en Campaña invites us to act not as voters but as activists committed to a certain democratic ideal. Thus, we must “troll” the acts of the main parties by painting posters, boycotting rallies, and exposing the personal secrets of the country’s various political acronyms. In this game, no particular organization is supported, although it is framed in a specific temporal space in which direct criticism, social action, and the media’s drive towards the political class centralized much of the public’s interest.

The parodic construction of the avatar and the political class

All of the sample games use the protagonists of the political class in a parodic way, either as the main characters of the ludic world or as antagonists to be defeated.

In the first case, Mariano Ninja puts us in the shoes of the President of the Government and establishes the action of the opponent’s elimination as a metaphor for the cuts carried out by the Executive. Thus, the player must “finish” Mr. Manolo (the pensioners), Crispin (actors), Artur (the Catalan independence movement), Ramon Nini (the young people who neither study nor work), Dr. Meredith (health), Mr. Rottenmayer (education), Toxo and Candido (unions) and Alfredo (the opposition). Cutting back these figures reduces the risk premium, and the aim is to avoid it reaching 600 points by “mistakenly” affecting other sectors represented by Fraülein Angela (the Troika), Monsieur Nicolas (the European right), José Mari (the Spanish right), Rouco (the Church), Mr. Onasis (the employers) or Iñaki & Juanca (the Royal House). As can be seen, this game synthesizes the action of cutting with an economist object and with asymmetry by sectors: it is bad to attempt against the de facto power, it is good to cut in the social sectors.

Other titles that place the politician as an agent of action are Safari King, Chorizos de España, Darsenas, Tesorero Corrupto, Alcalde Corrupto, Azota la Casta! and Spanish Fighters III. In all of them, the protagonist is a parodic version of the real image and his actions are trivialized and legitimized in a very specific and ludic framework. Thus, King Juan Carlos must kill elephants to win, Bárcenas must hand out envelopes or take money to a tax haven and a generic mayor must make illegal contracts. In all these cases, humor plays a catalytic role: it normalizes unethical actions, giving an interactive sense to the underlying social criticism. Fast game mechanics (usually focused on the accumulation of points) display their rhetorical sense by being reconciled with parodic fiction in a fully persuasive game experience: during the crisis, politicians have enjoyed absolute and shameful impunity. A different case is shown by the games Azota la Casta! and Spanish Fighters III. Here the mechanics and dynamics are typical of the genre (runner/platforms in the first, fighting in the second) but the action system does not reward the immoral attitude, but the messianic redemption of a Pablo Iglesias turned into a kind of social liberator. Thus, in Azota la Casta! Pablo Iglesias (although he can also be played as Pablo Echenique) will have to collect votes and throw chorizos against certain politicians of the Spanish right to gain popularity. The game shows some famous sentences of the political class intending to build an immoral and elitist “casta” that can only be defeated thanks to the performance of the leader of the Podemos party. Similarly, Spanish Fighters III centralizes the action in Iglesias, first against the journalist and director of the newspaper La Razón, Francisco Marhuenda (and, by extension, against the media structure of the Spanish right-wing) and later against Albert Rivera, leader of the political party Ciudadanos.

Source: CilupiaStudio (2015).

Figure 3 Azota la casta! or the messianic construction of Pablo Iglesias

The second major category of political representation in the sample makes the politician the antagonist of the game. This happens mainly in Marea Verde, a Plants vs. Zombies style game in which the school must protect itself from a political class that intends to destroy it. The hordes of politicians, made up of popular characters such as Cospe (María Dolores de Cospedal), Güert (José Ignacio Wert), Mariano (Mariano Rajoy) and Merkenstein (Angela Merkel), advance inexorably and the action of the game places us in the social defense of schools. The player will have to stop and eliminate the politicians by placing bookstores and throwing books, distracting their attention with envelopes full of bills or exploding loudspeaker systems. In this case, the rhetoric of the “zombie” provides a persuasive discourse of a dehumanizing, anti-cultural, and merely destructive nature, centralizing in the politician the disinterest and ineptitude of the one who attempts against the public educational model. In a similar line, Troll de Campaña operates by equating formal political activity with inaction and the “trolling” with the only way to vindicate, from the social bases, the foundations of the democratic model.

Therefore, both the temporary anchoring of the crisis’ milestones as ludofictional world and the parodic construction of the avatar and the political class contribute, from its simulation to the expression of a particular discursive form that treats the world of reference from the ludic perspective and, at the same time, from the factual perspective. This duality (the ludic and the factual) refers us, in fact, to the potential of learning by playing videogames. It is not about educational games as a product designed and oriented to the development of curricular content, but about massive digital games as a framework for learning social, political and economic realities, regardless of their formal and discursive treatment. A learning process that is especially critical and that operates at the heart of the true potential of contemporary video games: political-citizen training from ludic criticism, the understanding of procedural rhetoric, and the alternative discourses to the classic representational media thanks to the potential of ludic simulation.

REFERENCES

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games. The Expressive Power of Videogames. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5334.001.0001 [ Links ]

Capdevila, A. (2004a). El discurso persuasivo. La estructura retórica de los spots electorales en televisión. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.7203/puv-alg16-9575-2 [ Links ]

Capdevila, A. (2004b). La retórica del objeto: las partes retóricas como modelo para generar significados. Temes de Disseny, 21, 140-147. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Temes/article/view/29846 [ Links ]

Dolezel, L. (1999). Heterocósmica: ficción y mundos posibles. Arco Libros. [ Links ]

Eco, U. (1981). Lector in fabula. La cooperación interpretativa en el texto narrativo. Lumen. [ Links ]

Gómez, S. (2014). ¿Pueden los videojuegos cambiar el mundo?: Una introducción a los Serious Games. Unir Editorial. [ Links ]

Gómez, S. & Navarro, N. (2013). Videojuegos e Información. Una aproximación a los newsgames españoles como nueva óptica informativa. Icono 14, 11(2), 31-51. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v11i2.604 [ Links ]

Hunicke, R., Leblanc, M. & Robert, Z. (2004). MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI, 4(1). https://www.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/MDA.pdf [ Links ]

Juul, J. (2010). A casual revolution: Reinventing video games and their players. The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Lacasa, P. (2011). Los videojuegos. Aprender en mundos reales y virtuales. Morata. [ Links ]

Pericot, J. (1997). Transitar por los mundos posibles. Temes de Disseny, 14, 159-167. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Temes/article/view/29515 [ Links ]

Perelman, C. (1994). Tratado de la argumentación. La nueva retórica. Gredos. [ Links ]

Planells de la Maza, A. J. (2015a). Videojuegos y mundos de ficción. De Super Mario a Portal. Cátedra. [ Links ]

Planells de la Maza, A. J. (2015b). The expressive power of the Possible Worlds Theory in video games: when narratives become interactive and fictional spaces. Comunicação e Sociedade, 27, 289-302. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.27(2015).2102 [ Links ]

Planells de la Maza, A. J. (2017). Possible Worlds in Video Games: From Classic Narrative to Meaningful Actions. ETC Press. [ Links ]

Ryan, M. L. (1992). Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence and Narrative Theory. Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Salen, K. (2008). The ecology of games: connecting youth, games and learning. The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Squire, K. (2011). Video games and learning: Teaching and participatory culture in the digital age. Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

How to cite: Planells de la Maza, A. J. (2020). Video games as critical ludofictional worlds: the case of the Spanish political crisis in mobile digital entertainment (2008-2015). Comunicación y Sociedad, e7365. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7365

Received: January 17, 2019; Accepted: February 12, 2020

texto en

texto en