Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc n.33 Guadalajara Sep./Dec. 2018

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i33.7029

Transmedia Literacy

About the concept of transmedia literacy in the educational field. A review of the literature

1Universitat de Girona, España, juan.gonzalez@udg.edu; elisabet.serrat@udg.edu; meritxell.estebanell@udg.edu; carles.rostan@udg.edu; moises.esteban@udg.edu

Around the media movement of participatory culture, many educational approaches have already begun to speak of transmedia literacy. With a systematic review of the literature, we conclude that this concept has not yet been defined in the educational field, although there is consensus on some of its main components: transmediality, collaboration, prosumption and critical spirit.

Keywords: Literature review; transmedia; transmedia literacy; education

En torno al movimiento mediático de la cultura participativa hay ya muchos enfoques educativos que empiezan a hablar de una alfabetización transmedia. Con una revisión sistemática de la literatura, concluimos que este concepto no se ha definido aún en el ámbito educativo, aunque existe consenso sobre algunos de sus componentes principales: transmedialidad, colaboración, prosumo y espíritu crítico.

Palabras clave: Revisión de literatura; transmedia; alfabetización transmedia; educación

Introduction

In the last few years, a large number of works have been devoted to reviewing the scope of new digital cultures in the teaching and learning process (Gee, 2009, 2017; Ito et al., 2013; Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton & Robison, 2009). Among them, one of the emerging lines is formed by the so-called transmedia learning processes, which Raybourn (2012) defines as “a scalable messaging system that represents the narrative or core of an experience that unfolds through the use of different media platforms, engaging students emotionally in their learning and involving them personally in the story” (p. 471). This notion, without a doubt, is related to the works of Jenkins (1991, 2004, 2006) around the concepts of media convergence and processes of participatory culture, and, in turn, around a notion that is associated with it, that of transmedia literacy (or transmedialiteracy, or transliteracy) (Alper & Herr-Stephenson, 2013; Álvarez, Salavati, Nussbaum & Milrad, 2013; Fraiberg, 2017; Kline, 2010). This is of great interest from an educational point of view, as it will be the individuals with this literacy who will be able to participate fully in the participatory culture Jenkins speaks of.

Indeed, for Jenkins (2006) one of the main defining characteristics of this participatory culture is precisely media convergence, understood as the “flow of content across multiple media platforms, cooperation between multiple media industries and the migratory behaviour of media audiences, who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want” (Jenkins, 2006, p. 2). And there is no doubt that this new conception of the implicit collaborative processes requires citizens to cultivate new skills that enable their survival. It is, in broad terms, what brings us back to the concept of transmedia literacy.

In any case, the revolution that all this has resulted in is evident. If the traditional logic of the media was to produce cultural content, on a specific platform, for users to consume (unidirectional model of traditional television, for example), now people have been massively incorporated into the role of content producers, and move from one media platform to another (Jenkins, 2006; Jenkins et al., 2009). Put another way, people no longer observe what happens in the media, but can play an active role in its production (Lacasa, 2010). In fact, for over a decade, more than half of adolescents and young people (part of the generation called millennials) (Álvarez Monzonillo & de Haro, 2017) have been creating cultural content through digital media, and a third of Internet users share the content they produce (Lenhart, Madden & Hitlin, 2005). It is what, according to Jenkins, Ito and boyd (2016), is situated in the sphere of doing it together rather than doing it yourself. Or, this is what the Transmedia Literacy project (Scolari, 2018) intends to address, as it tries to take a step beyond the concept of media education and analyze the media practices of adolescents in both formal and informal contexts, while attempting to offer a taxonomy of components of this new literacy that are born from analysis of their daily practices (transmedia practices, as it could not be otherwise).

Throughout this conceptual framework, it is relevant not only to consider where the notion of transmedia can be situated, but also our understanding of what this transmedia literacy should be from the educational point of view, which is our scope of action. In Jenkins’ work, in general, we can identify two uses of the term transmedia, which, although they are related, appear with different purposes.

The first, perhaps the most widespread, links transmedia to an emergent form of discourse, of creating stories, of narrative (transmedia storytelling). In general, this use is the one that occupies the field of communication, due to the special intrinsic characteristicsthat it presents. Jenkins himself (2006) defines transmedia narrative or transmedia storytelling in the following way, which we quote from the Spanish version from two years later:

Transmedia storytelling refers to a new aesthetic that has emerged in response to media convergence-one that places new demands on consumers and depends on the active participation of knowledge communities […] A transmedia story unfolds across multiple media platforms, with each new text making a distinctive and valuable contribution to the whole. In the ideal form of transmedia storytelling, each medium does what it does best-so that a story might be introduced in a film, expanded through television, novels, and comics; its world might be explored through game play or experienced as an amusement park attraction (Jenkins, 2006, pp. 31-97).

The second use of the term is linked to a capacity, ability or competency (transmedia navigation), to a body of knowledge, skills and attitudes of the same individual who consumes and produces (who prosumes) these discourses. As educators, we can and must reflect on this literacy, which, again, ties in with advances in the categorization of the elements of this transliteracy by Scolari (2018)) in the context of the Transmedia Literacy project, funded by the European Union in the Horizon 2020 framework.

Also significant in this direction is the initiative of the MacArthur Foundation in relation to the construction of the area called Digital Media and Learning, in which the New Media Literacies project emerged. The Learning in a Participatory Culture project, of which Jenkins is the principal researcher, emanated from the White Paper of 2006, subsequently published by the MIT Press and entitled Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Jenkins et al., 2009). Its fundamental purpose is to identify and describe the cultural competencies and social skills necessary to participate fully in the new digital environments. Specifically, 12 skills and abilities are postulated, of which one of them is, precisely, transmedia navigation defined as “the ability to deal with the flow of stories and information across multiple modalities” (Jenkins et al., 2009, p. 46). In fact, this capacity is closely linked to the previously described processes of media and cultural convergence, which demand skills of processing, creation and dissemination of emerging forms of stories and arguments. Indeed, as these same authors state, “it involves the ability to both read and write across all available modes of expression ... learning to understand the relations between different media systems” (Jenkins et al., 2009, pp. 48-50).

Although Jenkins does not expressly mention the concept transmedia literacy, it is clear, as mentioned above, that there is an intimate relationship established between the media convergence of participatory culture, on the one hand, and the need for the individual to know how to operate in these digital environments in a new -and more profitable- way.

Having reached this point, the educational implications of these new concepts are evident. If we speak of a necessary competency for the exercise of citizenship in the 21st century, it is undeniable that education as a whole should ensure that new citizens acquire it. However, as far as we know, there is no consensus on the concept of transmedia literacy; rather, it is a notion we arrive at by confirming that transmedia (whether as a result of this new cultural model, or as a learning strategy) demands of the individual new skills that are not necessarily implicit in the concept of digital competence or digital skills, covered in the literature on many occasions (Gallardo Echenique, 2012; Bullen, Morgan & Qayyum, 2011). Thus, the objective of the review of the literature presented here is to identify and analyze the uses that have been made of the notion of transmedia literacy in the educational field. Our intention is to conceptually clarify the notion of transmedia literacy based on the uses that are collected in the specialized literature. More specifically, we aim to identify the elements that make up this literacy, as well as the preferred approach of the documents, or the perspective of addressing the concept of transmedia literacy.

Method

This systematic review of the literature draws on systematic and narrative approaches as an alternative to meta-analytic and traditional reviews (Okoli & Schabram, 2010). For our purposes, systematic review means the process of identification, selection and synthesis of primary research studies to provide a complete and current picture of the study subject (Crompton, Burke & Gregory, 2017). In this article, the review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the educational uses of the term transmedia literacy. We interpret the narrative approach to reviewing literature as the process of discussing the state of a subject, or specific topic, from a previous theoretical and contextual point of view, whose authority is commonly recognized. In this study, the contextual point of view is based on the foundational works of Jenkins, whose general perspective we have already analyzed succinctly in the introduction.

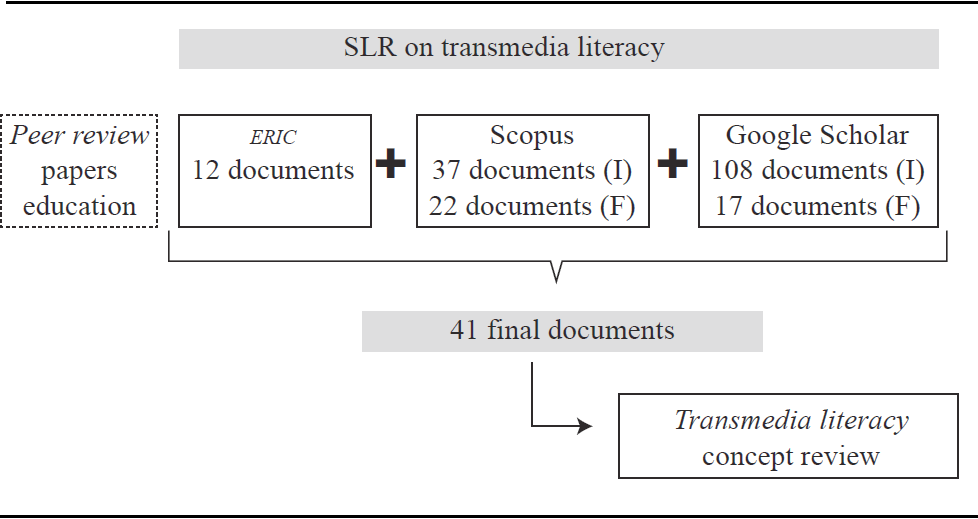

In our case, to achieve the proposed objective, we performed a search in three different academic repositories: the online library Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC), sponsored by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the U.S Department of Education; the Scopus search engine, of the Elsevier platform; and Google Scholar, as a massive open meta-repository. Only the terms alfabetización transmedia and transmedia literacy were introduced for the search (using quotation marks as Boolean search command, to guarantee syntagmatic concurrency in all results). All this was the first step of the process of constitution of the document database that is reflected in Figure 1:

As you can see, ERIC offered us 12 documents, which already met the quality requirements of being scientific articles and having passed a double-blind review process; in addition, due to the characteristics of the repository, they all came from the educational field. Scopus provided us with 37 initial documents (I), of which we discarded those that were not articles from scientific journals, those that had nothing to do with the educational field and those that we had already gathered from the search in ERIC, and which left us with 22 final documents (F). Finally, Google Scholar offered us 108 initial documents (I), which yielded 17 final documents (F) when applying the criteria we had previously established. In this case, the scarcity of documents did not force us to limit the search to any time window for operational considerations. For reasons of economy of space, we refrain from presenting the list of consulted documents at this point, and we will refer it indirectly in the results chapter, when analyzing their characteristics.

Framework of analysis / Categorization

The content of the analyzed texts was categorized according to the following characteristics: educational sector and stage, and type of study, including experimental research, review of studies, theoretical reflection, innovation, ethnography or educational experience, implicit or explicit concept of transmedia literacy, elements of the concept, description of the work and conclusions.

In this process, in addition to the reading, indexing, summary and parallel and cross-analysis of the documents, we enlisted the help of the qualitative data analysis software NVIVO 11 for Windows, which also allowed us to apply strategies of quantitative textual analysis (selective text searches, word count, graphic representations of the frequency of occurrences, etc.). Coding from selective textual searches was particularly useful, in that it allowed us to assemble a corpus of relevant fragments from which to analyze with greater precision the relationships between the concepts and the elements that make them up.

Results

In order to facilitate the reading of this section of presentation of the results and discussion, we first offer a general description of the analyzed documents, after which we take a careful look at the relevant concepts in a specific way.

Description of the documents

A first descriptive approach to the selected documents can be made from Table 1, in which we summarize their main characteristics.

Table 1 Characteristics of analyzed documents

| Document | Repository | Educational sector | Knowledge area | Type of article | Sample | |

| 1 | Alper (2013) | S, E | Formal | - | Reflection | - |

| 2 | Alper & Herr-Stephenson (2013) | S, E | Pre-school | Educational game | Reflection | - |

| 3 | Alvarez et al. (2013) | S, E | Formal | Maths | Experimental | 12 |

| 4 | Anderson (2014) | S, E | Formal | - | Reflection | - |

| 5 | Barber (2016) | S | Primary | - | Reflection | - |

| 6 | Checa-Romero (2016) | S | General | - | Innovation | 13 |

| 7 | Conner-Zachocki (2015) | S, E | Formal | Literacies | Ethnography | - |

| 8 | Establés-Heras (2016) | S | Formal | Fandom | Ethnography | 15 |

| 9 | Fleming (2013) | S, E | Formal Primary | - | Reflection | |

| 10 | Fraiberg (2017) | S | Informal | - | Case | 1 |

| 11 | Gambarato & Dabagian (2016) | E | Formal | General | Reflection | - |

| 12 | Gordon & Lim (2016) | S | Informal | - | Reflection | - |

| 13 | Grandío-Pérez (2016) | S | Formal Primary | General | Meta-analysis | - |

| 14 | Guerrero-Pico (2015) | S | Informal | Fan Fiction | Analysis | 304 |

| 15 | Gürsimsek (2016) | S | Univ. | GIF | Analysis | |

| 16 | Jover, González Martín, & Fuentes (2015) | S | Not formal | Citizenship | Reflection | - |

| 17 | Kline (2010) | GA | Not formal | Literature | Innovation | - |

| 18 | Llorente et al. (2013) | S, E | Formal Secondary | Maths | Reflection | 10 |

| 19 | López Yepes (2016) | S | Formal. | General | Reflection | - |

| 20 | Lugo Rodríguez (2016) | GA | Formal Secondary. | Transliteracy. | Experimental | 2 |

| 21 | McDougall & Potter (2015) | S, E | Formal | - | Reflection | - |

| 22 | Miočić & Perinić (2014) | S | Formal Primary | Literacies | Experimental | 321 |

| 23 | Moon (2016) | GA | Informal | Literacies | Analysis Discourse | - |

| 24 | Munaro, Dudeque, & Vieira (2016) | GA | Formal | Storytelling | Reflection | - |

| 25 | Pence (2012) | S, E | Formal | Internivel | Review Innovation | - |

| 26 | Pietschmann, Völkel, & Ohler (2014) | S | Formal Pre-school | General Storytelling | Reflection | - |

| 27 | Potter & Gilje (2015) | GA | Formal | Curación | Reflection | - |

| 28 | Ramasubramanian (2016) | S | Informal | Ethnicity Citizenship | Reflection | - |

| 29 | Rhoades (2016) | S, E | Formal Pre-school | Arts, books | Reflection Innovation | - |

| 30 | Richardson (2013) | GA | Formal | TIC | Reflection | - |

| 31 | Robinson (2015) | S | General | Literacies | Reflection | - |

| 32 | Roccanti &Garland (2015) | GA | Formal | Storytelling | Reflection | - |

| 33 | Rodrigues & Bidarra (2014) | S | Formal | Storytelling | Reflection | - |

| 34 | Scolari (2016) | GA | General | Literacies | Reflection | - |

| 35 | Soep (2012) | S | Not Formal | Literacies | Case | 1 |

| 36 | Soriano (2016) | S | Activism | Literacies | Reflection | - |

| 37 | Weaver (2015) | GA | Formal Primary | Literacies | Reflection | - |

| 38 | Weedon & Knight (2015) | S | General | Literacies | Editorial | - |

| 39 | Wiklund-Engblom, Hiltunen, Hartvik, Porko-Hudd, & Johansson (2014) | S, E | Formal Primary | STEM | Experimental | 11 |

| 40 | Witte, Rybakova, & Kollar (2015) | GA | Univ. | Teacher training | Reflection | - |

| 41 | Wohlwend (2012) | S, E | Formal Pre-school | Gender | Ethnography | 21 |

Acronyms: Google Scholar (GS); SCOPUS (S); ERIC (E).

Source: Compiled by the authors.

First, we gather the source of the documents, according to where we have taken them from: ERIC (E), Scopus (S) or Google Scholar (GS). Next, regarding the educational sector, we can see that most of them are in the sphere of formal education (27), while 5 of them are contextualized in informal education. The rest (9) address their reflection on transmedia literacy in a general educational context. In relation to the knowledge area to which they are assigned, the panorama is more varied, although transversal approaches abound from the area of literacies. Regarding the type of documents consulted, the theoretical reflections predominate (23), with less representation of experimental articles (5), innovations (4), ethnographic analyses (4) and documentary analyses (3), among others.

Quantitative analysis of the document database

As mentioned above, the use of the NVIVO qualitative analysis software enabled us to apply some quantitative analysis procedures based on the counting of the words with the most occurrences in the set of documents that we analyzed. The most frequently used words are reflected in Figure 2. Here, we can see that in addition to transmedia (with 1,789 occurrences in the works reviewed), the reference to media is pervasive (2,098 occurrences) followed by the words referring to the educational context in which we focus our reflection (students, 1,187 occurrences; education, 742; learning, 1,153), as well as the cultural and social context in which this approach takes place (culture, 480; social, 631). Finally, it is interesting to note that some of the elements that we will later highlight in the review of the elements also appear (literacy, 723; research, 528; information, 471; storytelling, 596; knowledge, 351; communication, 314). Also noteworthy is the mention of Jenkins, with a total of 426 occurrences, the only author appearing in the 50 most concurrent words. This shows, as described in the introduction, the origin of the concept in his work.

Concept of transmedia literacy

In the set of documents, it is not usual for the mention of transmedia literacy to be based on a definition in the strict sense. On the contrary, it is common to take for granted the concept alluded to, and move to focus directly on those aspects it is comprised of that we wish to highlight. Nevertheless, we do find some conceptual approaches that we could highlight as definitions of transmedia literacy or that we could interpret in that sense.

The oldest of these is expressed by Kline (2010), who attributes the birth of the concept to Jenkins, and assumes that talking about transmedia literacy implies understanding that students must simultaneously learn to navigate, create and evaluate different media. The idea of navigation, in effect, provides the backbone of Jenkins’ ideas (2006; Jenkins et al., 2009), insofar as it is considered that transmedia navigation is one of the relevant elements of what he calls new media literacies (hereinafter, NML); however, as far as we know, Jenkins does not properly refer to transmedia literacy (or, at least, he had not done so in his written works until 2010, which is when Kline assumes this definition). In any case, this idea of transmedia navigation, together with the other elements of NML, is present in the work of many authors who do in fact refer to them using the term Jenkinsian (Miočić & Perinić, 2014; Rhoades, 2016).

Other authors offer definitions of transliteracy that could be equivalent. Thus, for example, one can allude to the ability to read, write and interact within and across different genres, languages, media and contexts (Fraiberg, 2017), which adds the complexity of the multiplicity of national languages and identities. Or, in addition to the above, we can also focus on the idea that this capacity can be highly productive from the point of view of learning, especially if it focuses more on the contextual element than on the technological one (Grandío-Pérez, 2016).

Although not explicitly mentioning the label of media literacy in their definitions, many authors assume that the classic concept of digital or media competence, in the new transmedia context, is insufficient, and so must be enriched by other elements (Alper & HerrStephenson, 2013; Checa-Romero, 2016; Fleming, 2013; Gambarato & Dabagian, 2016; Lugo Rodríguez, 2016). A common idea, then, is that an individual who is only competent from the traditional digital point of view can hardly be considered competent in the context to which we alluded at the beginning, thus rendering what may be called traditional 21st century skills insufficient (Witte et al., 2015). To that effect, for example, elements are added such as critical spirit or the jump between media (Alper & Herr-Stephenson, 2013), the ability to interpret complex messages transmitted by different channels (Checa-Romero, 2016), or the focus is on navigation (Fleming, 2013), to which we have already referred (Jenkins et al., 2009). Finally, some proposals are documented in which attempts are made to agglutinate already existing literacies (Weedon & Knight, 2015), including the following: multimodal, critical, digital, media, visual, informational and ludic (Gambarato & Dabagian, 2016). Alternatively, this is complemented with elements of a transversal nature, such as creativity, sociability, mobility, accessibility or re-game (Rodrigues & Bidarra, 2014).

Elements that make up transmedia literacy

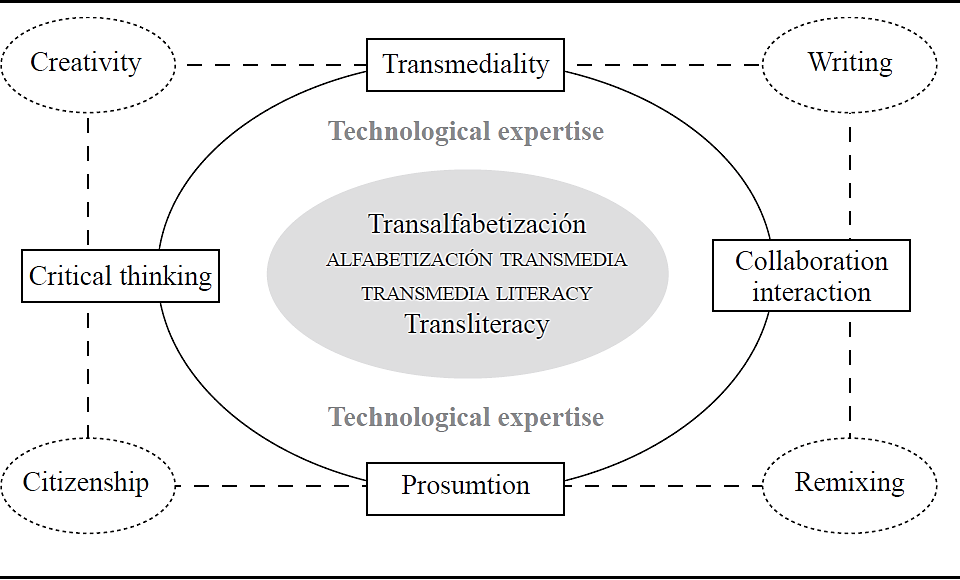

Beyond these definitions, what underlies all the documents is the emphasis on those additional elements that characterize the literacy of individuals who operate in transmedia as opposed to the digitally competent, and which should be considered from the educational perspective. These elements are shown in Figure 3, which provides a representation of the nuclear and secondary elements present in the concept of transmedia literacy throughout the documents analyzed:

As we see, we have tried to distinguish those that generate greater consensus and that, therefore, we consider nuclear; as opposed to those that, although they are highlighted by the literature, could constitute a second layer of characteristics owing to their lesser degree of agreement. In any case, there are four elements of this media literacy that are commonly accepted: transmediality, prosumption, critical spirit and collaboration or interaction. The first element, transmediality, is the one that links most directly with the NML of Jenkins (2009) and, specifically, with his notion of transmedia navigation. Indeed, this new literacy requires the ability to jump between media, following a narrative that develops sequentially or multimodally in different media (Alper, 2013; Álvarez et al., 2013; Anderson, 2014; Fleming, 2013; Fraiberg, 2017; Gambarato & Dabagian, 2016; Grandío-Pérez, 2016; Jover et al., 2015; Kline, 2010; Munaro et al., 2016; Pence, 2012), as well as the capacity to adopt analogue and digital media, both online and offline (Scolari, 2016).

Second, we find the leap from the individual consumer of media products to the individual who not only consumes them, but also produces them, the so-called prosumer. On the one hand, we cannot imagine, as we said before, that an individual is competent (literate) if they are not capable of producing media content in a context of participatory culture (where media becomes transmedia without exception) (Weaver, 2015); and, on the other, this idea not only affects adult individuals, but also children and adolescents, who must grow up in an environment in which they are expected not to be passive in the face of knowledge, but to create new tailored content as they learn. In short, we cannot demarcate the idea of transmediality of prosumption, because the jump between media not only involves changing the medium, but in many cases also entails switching roles between consumer and producer and vice versa (Gordon & Lim, 2016; Guerrero-Pico, 2015; Gürsimsek, 2016; Jover et al., 2015; Lugo Rodríguez, 2016; Roccanti & Garland, 2015; Scolari, 2016).

The alternation between consumption and production leads us to the context in which this occurs, a social context and not an individual one; and, therefore, it is essential to assess the importance of skills relating to collaboration and interaction in this participatory culture. It is what has been called collective intelligence or distributed cognition (Álvarez et al., 2013), or community-oriented creation (Ramasubramanian, 2016); and which, in one way or another, necessarily implies an interaction with other transmedia creators that goes beyond simple communication with them. Indeed, it is not enough to communicate or interact, but to collaborate in the service of the shared transmedia project (Anderson, 2014; Barber, 2016; Fraiberg, 2017; Gürsimsek, 2016; Lugo Rodríguez, 2016; Miočić & Perinić, 2014; Richardson, 2013; Roccanti & Garland, 2015). This, without a doubt, is quite attractive from the point of view of the educational focus of transmedia.

Finally, there is a continuous impact on an aspect that seems to deal more strictly with information literacy, but that acquires relevance in this context of convergent and participative culture; this aspect is the development of a critical spirit that allows us to discern, weigh, evaluate and improve not only other people’s products but also our own (Alper & Herr-Stephenson, 2013; Barber, 2016; Checa-Romero, 2016; Gambarato & Dabagian, 2016; Kline, 2010; López Yepes, 2016; Moon, 2016).

As we saw at the beginning of this epigraph, the list of components of media literacy is not limited to these four core elements, but it also encompasses additional elements, such as the exercise of citizenship through transmediality (Miočić & Perinić, 2014), which implies the assumption of new citizens’ codes and of new behavioural frameworks (Soep, 2012). This, in turn, opens the door to transmedia activism, which may have long-range impact (Soriano, 2016).

Regarding prosumption, we find a new vision of the processes of writing that takes the habitual linear and finalistic perspective (considering texts as something finalized) and moves to a new conception in which texts are revisited and reconstructed again and again (Barber, 2016; Fraiberg, 2017; Grandío-Pérez, 2016), always in search of improvements and updates of content dependent on what has been consumed and produced in other channels; and which, in turn, stimulates creativity to recreate what has already been created by oneself (Anderson, 2014). Finally, this idea is also linked to the concept of remix, as a product that does not emerge from nothing, but stems from previous, already encoded, transmedia products, which are decoded and recoded in search of new, better, more creative and more functional content (Pietschmann et al., 2014).

Last, to conclude this review of the elements that comprise the concept, we must emphasize the importance of technologies in transmedia literacy. There is no doubt that the extensive development of transmedia effectively started with the advent of Web 2.0 and, above all, thanks to Web 3.0. From this, it should be inferred that digital literacy-the advanced management of technology-should be a crucial element of transmedia literacy. Generally speaking, it is true that this follows indirectly, provided the concept is addressed, especially in the educational context that we have been exploring. However, the explicit omissions regarding its importance are conspicuous, to the point that this advanced management, which we have called technological expertise, is always implicit (it is pervasive); but it is not made explicit in a general way. Technology must be used efficiently, but transmedia literacy transcends the purely technological and focuses more on use, user and context than on the technical component (Grandío-Pérez, 2016; Roccanti & Garland, 2015).

Discussion and conclusions

In reviewing both the explicit notions of transmedia literacy and its constituent elements in light of Jenkins’ theories of participatory culture and media convergence (Jenkins 2006), there are two ideas that outweigh any other consideration. The first is that, although explicitly recognized as such in few cases, the current frame of reference is based on the NML of this same author (Jenkins et al., 2009). And the second, partially a consequence of this, has to do with the inexistence of a concept developed as such in the literature, which compels us to highlight a void in that regard.

In relation to the first idea, it is obvious that the elements we have pointed out (prosumption, transmediality, critical spirit and collaboration) are related to some of the skills that were already being considered in 2009 and that acquire relevance when it comes to preparing individuals for the new participatory culture. We are speaking, for example, about appropriation, transmedia navigation, judgement or networking (Jenkins et al., 2009), as underlying concepts on which the consulted literature has focused, as far as we know. However, when talking about transmedia literacy, it is important to centre attention on some of the 12 NML, which acquire a special relevance. And that is, in our view, the contribution of this new concept. We speak of prosumption as a nuclear and unselectable aspect: the transmedia individual does not choose whether to jump into the production of transmedia content and materials, but is a creator by default, in parallel with their transmedia peers (Álvarez et al., 2013; Gordon & Lim, 2016; Guerrero-Pico, 2015; Gürsimsek, 2016; Jover et al., 2015; Lugo Rodríguez, 2016; Ramasubramanian, 2016; Roccanti & Garland, 2015; Scolari, 2016). And this leads them to be natural remixers, who will always start from previous content and who, in turn, will be the previous link in the creation process of the next transmedia individual (Barber, 2016; Grandío-Pérez, 2016; Fraiberg, 2017). As we stated earlier, we are not speaking of the condition of being a sporadic or occasional producer, which could be implicit in NML, but of a proactive action of being one habitually. On the other hand, it is not only this, but the fact that all of this must be carried out in the frameworks of digital citizenship (Alper, 2013; Miočić & Perinić, 2014; Soep, 2012; Soriano, 2016), as the capacity for judgment implicit in the NML is not sufficient, but must be guided by ethical principles that govern actions in participatory culture. This understanding, of course, exceeds the usual limits of reflection on media culture, providing a holistic component that overcomes the formal constriction of literacy and media consumption processes; and, without being able to say that it contributes something that was not implicitly present in the Jenkinsian models, it does offer an interesting deliberation in the service of a more productive engagement of the individual both in their immediate context and in the digital society that embraces them (Scolari, 2018).

In relation to the second idea, we are clear that there is no consensus on the adoption of a definition of this literacy. However, there is consensus in recognizing that, whatever that definition may be, it must agglutinate and harmonize a large number of other previous competencies (Weedon & Knight, 2015) that go beyond digital competence or 21st century skills, which would be the closest concept (Witte et al., 2015). Above all, it implies a change in the previous epistemological configurations of the competencies from which it may derive (in essence, regarding the change of role towards prosumption). Perhaps, therefore, we should endorse the two-layer representation that provides this contribution to the concept of transmedia literacy in Figure 3, which can be taken as a general reference both for citizens in general, as well as for their orientation in the educational sphere, with all people, and not only with adults (see, in fact, how the Transmedia Literacy project of the European Union in Horizon 2020 advocates precisely for this literacy in adolescents).

Therefore also, beyond this reflection on the concept and elements that comprise it, our review of the literature also leads us to consider that addressing transmedia literacy from the educational field can facilitate the adoption of immersive strategies, in which disbelief is suspended in the service of learning (Conner-Zachocki, 2015; Robinson, 2015), and in which we can harness the flow of dynamic content that facilitates learning (Wiklund-Engblom, Hiltunen, Hartvik, & Porko-Hudd, 2013), and engages the student (Soriano, 2016). In effect, from an educational point of view, in all stages (albeit with different levels) transmedia literacy is the passport to the use of media platforms in a massive and intensive way, as optimal scenarios for community learning (Pence, 2012). A learning focused on content and context, and not on technology (Grandío-Pérez, 2016), is, at the same time, a way to combat the multiple digital gaps that participatory culture can give rise to among “illiterates” (Alper, 2013). Unfortunately, the limitations faced by teachers are obvious: the concept is not operationalized as an approach for educational purposes, nor have we systematically explored what may be the most appropriate pedagogical and didactic approaches for doing so. All of this is, then, a path that educational research must follow to take full advantage of the wealth of opportunities that transmedia (and transmedia literacy) can provide in terms of learning.

Acknowledgements

This research has been developed with funding from the Institut de Ciències de l’Educació Josep Pallach of the University of Girona, within the context of the aid to Teaching Innovation Groups (TIG on Transmedia and Education).

REFERENCES

Alper, M. (2013). Developmentally appropriate New Media Literacies: Supporting cultural competencies and social skills in early childhood education. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 13(2), 175-196. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798411430101 [ Links ]

Alper, M. & Herr-Stephenson, R. (2013). Transmedia Play: Literacy Across Media. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 5(2), 366-369. Recuperado de http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle/vol5/iss2/2/ [ Links ]

Alvarez, C., Salavati, S., Nussbaum, M., & Milrad, M. (2013). Collboard: Fostering new media literacies in the classroom through collaborative problem solving supported by digital pens and interactive whiteboards. Computers and Education, 63, 368-379. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.019 [ Links ]

Álvarez Monzonillo, J. M. & de Haro, G. (2017). Millennials. La generación emprendedora. Barcelona: Ariel/Fundación Telefónica. [ Links ]

Anderson, T. D. (2014). Making the 4Ps as important as 4Rs. Knowledge Quest, 42(5), 42-47. [ Links ]

Barber, J. F. (2016). Digital storytelling: New opportunities for humanities scholarship and pedagogy. Cogent Arts and Humanities, 3(1), 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1181037 [ Links ]

Bullen, M., Morgan, T., & Qayyum, A. (2011). Digital Learners in Higher Education: Generation is Not the Issue. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 37(1), 1-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21432/T2NC7B [ Links ]

Checa-Romero, M. (2016). Developing skills in digital contexts: Video games and films as learning tools at primary school. Games and Culture, 11(5), 463-488. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015569248 [ Links ]

Conner-Zachocki, J. (2015). Using the digital transmedia magazine project to support students with 21st-century literacies. Theory Into Practice, 54(2), 86-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.201 5.1010835 [ Links ]

Crompton, H., Burke, D., & Gregory, K. H. (2017). The use of mobile learning in PK-12 education: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 110, 51-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.03.013 [ Links ]

Del Mar Grandío-Pérez, M. (2016). El transmedia en la enseñanza universitaria. Análisis de las asignaturas de educación mediática en España (2012-2013). Palabra Clave, 19(1), 85-104. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2016.19.1.4 [ Links ]

Establés-Heras, M. -J. (2016). Entre fans anda el juego. Audiencias creativas, series de televisión y narrativas transmedia. Opción: Revista de Ciencias Humanas Y Sociales, 11, 476-497. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5866919 [ Links ]

Fleming, L. (2013). Expanding Learning Opportunities with Transmedia Practices: Inanimate Alice as an Exemplar. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 5(2), 370-377. Recuperado de http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle/vol5/iss2/3/ [ Links ]

Fraiberg, S. (2017). Pretty bullets: Tracing transmedia/translingual literacies of an israeli soldier across regimes of practice. College Composition and Communication, 69(1), 87-117. [ Links ]

Gallardo Echenique, E. E. (2012). Hablemos de estudiantes digitales y no de nativos digitales. UT. Revista de Ciències de l’Educació, 7-22. [ Links ]

Gambarato, R. R. & Dabagian, L. (2016). Transmedia dynamics in education: the case of Robot Heart Stories. Educational Media International, 53(4), 229-243. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2 016.1254874 [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (2009). New Digital Media and Learning as an Emergin Area and “Worked Examples” as One Way Forward. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (2017). Teaching, Learning, Literacy in Our High-Risk HighTech World. A Framework for Becoming Human. Nueva York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Gordon, I. & Lim, S. S. (2016). Introduction to the special issue “Cultural industries and transmedia in a time of convergence: Modes of engagement and participation”. Information Society, 32(5), 301-305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2016.1212614 [ Links ]

Grandío-Pérez, M. M. (2016). El transmedia en la enseñanza universitaria. Análisis de las asignaturas de educación mediática en España (2012-2013). Palabra Clave. Revista de Comunicación, 19(1), 85-104. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2016.19.1.4 [ Links ]

Guerrero-Pico, M. (2015). Producción y lectura de fan fiction en la comunidad online de la serie Fringe: transmedialidad, competencia y alfabetización mediática. Palabra Clave. Revista de Comunicación, 18(3), 722-745. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.3.5 [ Links ]

Gürsimsek, Ö. A. (2016). Animated GIFs as vernacular graphic design: producing Tumblr blogs. Visual Communication, 15(3), 329-349. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357216645481 [ Links ]

Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., Schor, J., & Watkins, C. S. (2013). Connected Learning: an agenda for research and design. Irvine: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. Recuperado de http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/48114/ [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (1991). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Nueva York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2004). The Cultural Logic of Media Convergence. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 7(1), 33-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877904040603 [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. Nueva York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2008). Convergence culture. La cultura de la convergencia de los medios de comunicación. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H., Ito, M., & Boyd, D. (2016). Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: a Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., & Robison, A. J. (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture. Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Jover, G., González Martín, M. D. R., & Fuentes, J. L. (2015). Exploración de nuevas vías de construcción mediática de la ciudadanía en la escuela: De Antígona a la narrativa transmedia. Teoria de La Educacion, 27(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teoredu20152716984 [ Links ]

Kline, D. T. (2010). Metamedievalism, Videogaming, and Teaching Medieval Literature in the Digital Age. En T. Kayalis & A. Natsina (Eds.), Teaching Literature at a Distance. Open, Online and Blended Learning (pp. 148-162). London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Lacasa, P. (2010). Children transmedia and virtual experiences inside and outside the classrooms. En L. Wong, S. C. Kong & F. Y. Yu (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18 th International Conference on Computers in Education: Enhancing and Sustaining New Knowledge Through the Use of Digital Technology in Education (pp. 663-667). Malasia: Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education. [ Links ]

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., & Hitlin, P. (2005). Teens and technology: Youth are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation. Washington, D.C.: Pew Internet and American Life Project. [ Links ]

Llorente, C., Pasnik, S., Moorthy, S., Hupert, N., Rosenfeld, D., & Gerard, S. (2013). Preschool Teachers Can Use a PBS KIDS Transmedia Curriculum Supplement to Support Young Children’s Mathematics Learning: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. A Report to the CPB-PBS Ready to Learn Initiative. En SREE (Ed.), Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness Spring 2015 Conference (pp. 1-5). Evanston: SREE. [ Links ]

López Yepes, A. (2016). Biblioteca universitària i entorns audiovisuals en obert: estat de la qüestió i proposta d’actuacions. BiD: Textos Universitaris de Biblioteconomia I Documentació, 36(36). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1344/BiD2016.36.18 [ Links ]

Lugo Rodríguez, N. (2016). Diseño de narrativas transmedia para la transalfabetización (Tesis doctoral inédita). Universitat Pompeu Fabra, España. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10803/396131 [ Links ]

McDougall, J. & Potter, J. (2015). Curating media learning: Towards a porous expertise. E-Learning and Digital Media, 12(2), 199-211. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753015581975 [ Links ]

Miočić, B. & Perinić, J. (2014). New media literacy skills of youth in Zadar. Medijska Istrazivanja, 20(2), 231-254. Recuperado de https://hrcak.srce.hr/133863 [ Links ]

Moon, M. R. (2016). “Thought We Wouldn’t Notice, but We Did”: An Analysis of Critical Transmedia Literacy Among Consumers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (Tesis de maestría inédita). Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, Estados Unidos. Recuperado de https://tamucc-ir.tdl.org/tamucc-ir/handle/1969.6/678 [ Links ]

Munaro, A. C., Dudeque, A. M., & Vieira, P. (2016). Use of Transmedia Storytelling for Teaching Teenagers. Creative Education, 7(7), 1007-1017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.77105 [ Links ]

Okoli, C. & Schabram, K. (2010). A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research. Working Papers on Information Systems, 10(26), 1-51. DOI: https://doi. org/10.2139/ssrn.1954824 [ Links ]

Pence, H. E. (2012). Teaching with Transmedia. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 40(2), 131-140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2190/ ET.40.2.d [ Links ]

Pietschmann, D., Völkel, S., & Ohler, P. (2014). Transmedia Critical Limitations of Transmedia Storytelling for Children: A Cognitive Developmental Analysis. International Journal of Communication, 8(0), 2259-2282. Recuperado de http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/2612/1205DANIEL [ Links ]

Potter, J. & Gilje, O. (2015). Curation as a new literacy practice. Journal of E-Learning and Digital Media, 12(2), 123-127. DOI: 10.1177/2042753014568150 [ Links ]

Ramasubramanian, S. (2016). Racial/ethnic identity, community-oriented media initiatives, and transmedia storytelling. Information Society, 32(5), 333-342. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2016.1212618 [ Links ]

Raybourn, E. M. (2012). Beyond serious games: Transmedia for more effective training & education; education. En A. Bruzzone, W. Buck, F. Longo, J. A. Sokolowski & R. Sottilare (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Defense and Homeland Security Simulation Workshop 2012 (pp. 6-12). Genova: Dime Università di Genova. [ Links ]

Rhoades, M. (2016). “Little Pig, Little Pig, Yet Me Come In!” Animating The Three Little Pigs with Preschoolers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(6), 595-603. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0743-0 [ Links ]

Richardson, W. (2013). Students First, Not Stuff. Technology-Rich Learning, 70(6), 10-14. Recuperado de http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar13/vol70/num06/StudentsFirst,-Not-Stuff.aspx [ Links ]

Robinson, L. (2015). Multisensory, Pervasive, Immersive: Towards a New Generation of Documents. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(8), 1734-1737. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1002/asi.23328 [ Links ]

Roccanti, R. & Garland, K. (2015). 21st Century Narratives: Using Transmedia Storytelling in the Language Arts Classroom. Signal Journal, 38(1), 16-20. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, P. & Bidarra, J. (2014). Transmedia storytelling and the creation of a converging space of educational practices. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 9(6), 42-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v9i6.4134 [ Links ]

Scolari, C. A. (2015). La hora del prosumidor. El Cactus, 4(4), 24-26. [ Links ]

Scolari, C. A. (2016). Alfabetismo transmedia: estrategias de aprendizaje informal y competencias mediáticas en la nueva ecología de la comunicación. Revista TELOS. Cuadernos de Comunicación e Innovación, 103, 13-23. Recuperado de https://repositori.upf.edu/ handle/10230/27788 [ Links ]

Scolari, C. A. (2018). Adolescentes, medios de comunicación y culturas colaborativas. Aprovechando las competencias transmedia de los jóvenes en el aula. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Recuperado de https://repositori.upf.edu/handle/10230/34245 [ Links ]

Soep, E. (2012). The digital afterlife of youth-made media: Implications for media literacy education. Comunicar, 19(38). DOI: https:// doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-10 [ Links ]

Soriano, C. R. R. (2016). Transmedia mobilization: Agency and literacy in minority productions in the age of spreadable media. Information Society, 32(5), 354-363. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.20 16.1212620 [ Links ]

Weaver, T. (2015). Blurred Lines and Transmedia Storytelling: Developing Readers and Writers Through Exploring Shared Storyworlds. Signal Journal, 38(1), 23-26. [ Links ]

Weedon, A. & Knight, J. (2015). Media literacy and transmedia storytelling. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 21(4), 405-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515601656 [ Links ]

Wiklund-Engblom, A., Hiltunen, K., Hartvik, J., & Porko-Hudd, M. (2013). Transmedia storybuilding in Sloyd. En I. A. Sánchez & P. Isaías (Eds.), Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Mobile Learning 2013 (pp. 199-203). Lisboa: IADIS. [ Links ]

Wiklund-Engblom, A., Hiltunen, K., Hartvik, J., Porko-Hudd, M., & Johansson, M. (2014). “Talking Tools”: Sloyd Processes Become Multimodal Stories with Smartphone Documentation. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 6(2), 41-57. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4018/ijmbl.2014040104 [ Links ]

Witte, S., Rybakova, K., & Kollar, C. (2015). Framing Transmedia: Pre-service Teachers’ Transmedia Interactions with Young Adult Literature Narratives. Signal Journal, 38(1), 27-33. [ Links ]

Wohlwend, K. E. (2012). The boys who would be princesses: playing with gender identity intertexts in Disney Princess transmedia. Gender and Education, 24(6), 593-610. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2012.674495 [ Links ]

Received: December 14, 2017; Accepted: May 22, 2018

text in

text in