Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicación y sociedad

versão impressa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.32 Guadalajara Mai./Ago. 2018

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i32.6924

General theme

Contact orbits on Facebook. Intimacy, sociability and friendship in adolescents from popular sectors in Buenos Aires

1 University of Buenos Aires-CONICET/University of Lanús E-mail: joaquinlinne@gmail.com

This article addresses the types of friendship established by teenagers from popular sectors of Buenos Aires on Facebook. At the methodological level, a virtual ethnography and in-depth interviews were carried out. Among the results, it is observed that their friendships differ according to components that we call here “shared spaces”, “common histories”, “affectivity” and “endurance”.

Keywords: Adolescents; popular sectors; Facebook; sociability; friendship

Este artículo aborda los tipos de amistad que establecen adolescentes de sectores populares de Buenos Aires en Facebook. A nivel metodológico, se realizó una etnografía virtual y entrevistas en profundidad. Entre los resultados, se observa que sus amistades se diferencian según componentes que aquí denominamos “espacios compartidos”, “historias en común”, “afectividad” y “aguante”.

Palabras clave: Adolescentes; sectores populares; Facebook; sociabilidad; amistad

Introduction

Contemporary adolescents, who accumulate thousands of hours using information and communication technologies (ICT), find in these devices a meeting place with friends and peers (Urresti, Linne & Basile, 2015). The introduction of ICT’S in their daily life entails new forms of sociability, which we must continue to investigate from the social sciences (Morduchowicz, 2012, Rosa, Santos & Faleiros, 2016). This article explores the contact networks in Facebook of adolescents from popular sectors of Buenos Aires, based on a qualitative methodology based on interviews and a virtual ethnography that takes up elements of the analysis of networks (Rodríguez Treviño, 2013).

Following the classic conceptualization of Simmel (2002), sociability is the playful form of socialization. Now, what does it mean to socialize in Facebook? Here you can understand the interactions between friends and strangers -apparently, undifferentiated under the category of “friends” by the network itself- that imply some playful meaning: chatting, playing, seducing, commenting on images, videos or texts, giving and exchanging “I like it” (like). Such interactions may include publications with a greater commitment: making comments or affectionate posts. In this sense, they are a privileged channel to understand the different types of contacts that this population deploys in the social network.

According to boyd (2014), adolescent sociability is framed around the Facebook platform. For Assunção and Matos (2014), friendships in this network are basically extensions of copresential friendships, while Morduchowicz (2012) argues that adolescent sociability unfolds in an offline-online continuum. In the same way, it can be thought that friendship unfolds in an analogous context. In this way, outputs, declarations of affection and games with phenomena arising from the overcrowding of ICT’S are intertwined. Although the state of the question has explored different forms of sociability in popular areas (Auyero & Berti, 2013, Capriati, 2014, Kessler & Dimarco, 2013, Merklen, 2005, Silba, 2009, among others), the massification of ICT in a global level and in particular, in the population studied in this article, requires further analysis. Thus, the intention is to investigate emerging phenomena. How specifically are friendship and sociability spread in teenagers from low-income sectors, who have taken this platform as the central space of their online life? In this article, it is postulated that its recurrent expressions in Facebook, which have a different tone from other publications of the network, allow us to approach their practices in a singular way and to know more about them.

Adolescence is a central stage of identity configuration in which exploratory practices are key, affective containment, intense identification with the peer group, the search for greater autonomy vis-à-vis parents, and the need to shape and consolidate friendship groups (Krauskopf, 2000, Margulis & Urresti, 1996). With the massification and adoption of ICTS in the daily lives of a vast majority of adolescents, this identity configuration and these exploratory practices are usually associated with the profile that young people construct in Facebook (Urresti, Linne & Basile, 2015). In this sense, it is chosen as a platform for analysis because it has become the largest social networking website worldwide and one of the central communication and entertainment spaces for contemporary adolescents (boyd, 2014; Morduchowicz, 2012; Urresti, 2012; van Dijck, 2016). For the studied population, Facebook works in a certain way as a synonym of the Internet, since there they deploy most of their online actions.

Now, the very denomination of “friends” proposed by Facebook should not obstruct the differences of the links observed in the platform. Although the ICT’S allow new forms of sociability and friendship, numerous recent investigations conclude that the copresential dimension for the conformation of amical bonds is still fundamental (Linne, 2015, Morduchowicz, 2012, Rosa, Santos & Faleiros, 2016, van Dijck, 2016).

This article aims to explore and describe the different types of sociability and friendship links that this population develops in the platform. For this, the category “contact orbit”2 is postulated in order to account for the links with characteristics and dynamics specific described in terms of a series of components recurrently in their publications.

Methodology

This research, arising from a doctoral thesis, is exploratory and qualitative: it is based on an unintentional sample of 20 in-depth interviews with adolescents from the popular sectors of the Buenos Aires. In addition, it is based on virtual observations made on the Facebook platform between 2012 and 2016. The research subject is constructed at the intersection of two variables: age and the social sector. Regarding the first variable, within the category “youth”, which has been defined by different authors as a sociocultural construction (Krauskopf, 2000, Margulis & Urresti, 1996), this article focuses on adolescents, who are defined as those who are between 13 and 18 years old. Here the lower limit of 13 years is taken as the beginning of adolescence, given that it is the average age at which they usually start secondary school, which entails a more active sociability. This choice does not ignore that youth -and also adolescence- is a complex notion that can not be essentialized or defined only by its age situation, given that it is crossed by cultural, socioeconomic and gender issues (García Canclini, Cruces & Urteaga, 2012; Valenzuela, 1997). The age limits are useful for analytical purposes, but adolescence and youth cannot be defined only from the age, as also Margulis and Urresti (1996) warn. Regarding the second variable, here it is proposed to study the adolescents from low-income sectors, who were defined according to the type of work and educational level of their parents, and from the lack or possession of basic social services in the neighborhood and housing. Indeed, the neighborhoods from low-income sectors -especially in marginal settlements- often lack paving, sewage drainage, lighting, sweeping and cleaning; as well as hospitals, schools or police stations. On the other hand, on the basis of data from the National Institute of Statistics and Census [INDEC] (2012), parents of adolescents are defined as those who have less than ten years of education and are usually salaried workers of medium or low qualification.

The exploratory nature of this work is related to the fact that this digital tool (Facebook), quickly appropriated by the adolescents from low-income sectors, was available for this population since 2008, when its spanish version was created, two years after its international diffusion in English. As a contact mode to generate the intentional sample, the “snowball” strategy was used on numerous occasions, which facilitates and in turn uses Facebook, by constantly suggesting that common contacts be added to the network.

To carry out the research, between 2012 and 2016 a profile created ad hoc in Facebook was maintained: the profile had a picture of an overweight male disguised as Batman and a caricature of Homer Simpson, both obtained through Google images. The age of the profile user was not specified. Those who asked for a message or chat for the identity of the profile were informed about the profession and age of the author. Only the purposes of the investigation were made explicit to those who requested it by chat or private message. In those cases, the objectives of the research were discussed: to investigate the ways in which young generations present themselves in social networks. It is clarified that the virtual observation was non-participant, in the sense that it did not interact with the contacts of the social network, other than giving a few likes. From the profile I just observed the interaction, the creation of profiles and the posts of the users of the intentional sample.

Orbits of contacts around the personal profile

After four years of observations, hundreds of images and texts collected in a series of relational components were classified, in order to investigate the different degrees of adolescent sociability in Facebook. These components were configured in four categories: “shared spaces”, “stories in common”, “affectivity” and “endurance”. The shared spaces refer to the co-presidents of the school, the neighborhood, the nightclub, the bar, the shopping center and the soccer field. The stories in common allude to the fact of spending part of their lives in the same spaces. The affectivity is connoted by expressions of affection that are exchanged in the network. At this point, it is necessary to return to the concept of “endurance” culture (Alabarces & Rodríguez, 2008), central in the universes of meaning of this population. This native category originally refers to certain associations of meaning and practices linked to the capacity to withstand the adverse moments of the soccer club, such as division descents and clashes with other “bars”. This culture of “endurance” then acquired other modulations, associated with the “culture of the explosion” and different ways of externalizing masculinity and being “legitimate”. As Urresti (2007, p. 283) points out, for young people from Buenos Aires “endurance implies fidelity, support, permanence”.

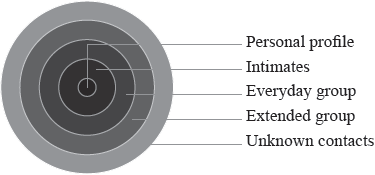

From observing the interactions traversed by this series of elements in common, the following scheme is proposed in which the types of contacts in Facebook are illustrated according to the different degree of intensity. These revolve around the personal profile, understood as its own node: 1) with “intimate” refers to the contacts with which space, stories, affectivity and “endurance” are shared; 2) with “daily” refers to the contacts with whom all the elements mentioned in category 1 are shared, except “endurance”; 3) with “extended” 4 is intended to account for those intermediate contacts between “daily” and “unknown”, with whom only certain spaces and stories in common are shared; 4) with “unknown” refers to those accepted within the network, whose only requirement is to have contacts in common. It should be noted that the proposed categories are interrelated and refer to changing relationships that vary according to the dynamics of the interactions and the passage of time. Of the hundreds or thousands of contacts that each adolescent tends to have, the great majority tends to interact in Facebook with only a few tens. First of all, with his intimates, who are usually no more than ten. Secondly, with their daily groups (schoolmates and neighborhood peers), which usually do not exceed 100. The known copresentials of the extended group3 usually amount to 100 or, at the most, 00. The other contacts are part of the extended group that are not known co-face-to-face (that is, they are friends of friends, relatives of friends, acquaintances of acquaintances), or directly strangers with whom contacts are shared. This shows that, if on average the adolescents in the sample have around 1 000 contacts, most of them are unknown. The bulk of the interactions unfold with the intimates and with the daily group. To analyze these interactions, a categorization of the different types of sociability and “friendship” between contacts is presented in the following figure.

As has been pointed out, at one extreme, the intimate are those who share in a greater degree the observed elements of shared spaces, common history, affectivity and endurance. At the other end of the proposed categorization, strangers represent the zero point of these elements in common. Since in Facebook all contacts they are called “friends”, here a typology is drawn that discriminates the different types of “friendship”.

Intimates

Intimate contacts represent the orbit of sociability closest to one’s profile, with whom one shares more time, both online and offline. They usually belong to the same age group and, on numerous occasions, they are even the same age. The main activities they carry out are chatting, posting publications in common, making comments, “liking” and playing. In many observed publications, adolescents present to the group of intimates with whom they share their daily life and, in turn, present themselves as part of that group that defines and identifies them. In this way, they honor their best friends, tell them that they love them and are fundamental in their lives. Such publications tend to have a high degree of acceptance and feedback among their network of contacts.

In many publications, adolescents are observed expressing their intimate friendships that have a lot of affection (“I love them”, “they are everything for me”). They also usually post personal photos with their group of intimates. Although his words do not show a marked affectivity, the closeness of the embraced bodies suggests that they are intimate. Similarly, in another post, a teenager (14 years) presents an image with an intimate and adds “with the most piola I knew in my life I love you, you are the most”. In another, a teenager (15 years old) expresses her affection to her group of intimate males, by publishing that “they are everything, they are my life ..., they are fun, good, friendly, tared more than anything but I love them and I can not be without you”.

In another image, a teenager (16 years old) emphasizes that his group of intimates (present in the photo) are his “ranchada”,4 that “loves” them and “they are everything”. This affective expressiveness with “homelike” references gives an account of the centrality that intimates possess for them. In another example there are several personal photos of a teenager with her intimate group. In addition to showing her corporality in a group, she introduces her friends, among whom are listened to, they consult each other through chat and inbox, and on weekends they perform “previous” and go out to dance. As one adolescent interviewed (17 years old) comments, “on weekends we go single with my sister and my friends to look for nice guys that are worthwhile. And then in the week, if we met someone, we followed them on Facebook.”

As it was revealed in hundreds of images, teens often combine a photo with their best friend or with their intimate group, which is sometimes mixed. In popular areas, in the many cases of conflicting family relationships and lack of resources, the intimate often function as brothers. This is evident in the way they are called: “rancho” and “ranchada”.

On the other hand, among intimate can also exist -like tests of trust- the exchange of passwords or the intrusion in the profile of others, as seen in the following example: “Te Usurpé el face Solo Paaraa Deeciirtee q tii amoo muuchoo amiigaa & paaraa agraadeeceertee everything you do x my & xq you’re always when Tee Neeceesitoo” (Woman, 16 years). These interactions work as proof that they are intimate, that they protect one another and take care of the “virtual territory” (their profile and image in the network).

In turn, they represent the degree of mutual surrender, in the sense of trusting fully in the other and having nothing to hide. The exchange of passwords or the intrusion into someone else’s profile implies a specific netiquette5: only look at the virtual spaces of the other but not interact, except to make an affective publication. This type of experience deepens the bond and increases the mutual commitment of endurance. Sometimes an excess of confidence and actions on the part of one of those involved in the password exchange triggers a conflict around the privacy of the profile.

In intimate publications are also frequent statements of love and gratitude that, sometimes, allude to “the best” intimate friendship, native category that allows understanding this type of contact. Having a “better” implies a favorite friendship that works as a brother / sister, whose function is that of confidant: “you are all in my life”, “I love you”, “I am jealous”. This link combines elements of relationships between siblings, couples and childhood friends. Although a priori does not imply a blood link, in popular areas it is common for two sisters to be “better”. In addition to obligations and privileges similar to those of other intimates, it also usually requires certain exclusivity and demands a significant amount of time: “the” or “the best” is supposed to always be available to “bank” the other, as well as to support with a like and a complimentary comment. If both are online, it is expected that they defend each other before conflicting publications. Also, this relationship can be changing and mobile according to the sex-affective cues of each and the conflicts that arose. If one of the two “best” couples, it usually happens in conflicts of those between the couple and “the best”. In another publication of Facebook, a teenager (16 years old) thanks her friendship for her “best”. She expresses to him that he loves her, that his friendship is more than being friends, that he always trusts her to tell her secrets, thanks that he always listens to her and accepts her as he is. She reminds him never to hesitate to call her and that he will always be with her for anything, regardless of the others. This communication dynamics feeds on the virtual and copresential daily sociability.

Several examples were observed that account for this frequent social relationship among adolescents from low-income sectors: that of “better” male-female. In many publications, the teenager is grateful to be their “best” to their intimate, or vice versa and also publish some photos in which they are happy.

In a particular case, a teenager (17 years old), to justify his virile condition and his intimate relationship (but not sex-affective) with a woman, says “I love you a lot, even if you are a lesbian”, although he clarifies that it is a joke and that she knows that “he always jokes her with that”. These common publications among these adolescents point to a tension between the traditional heteronormative model and certain socio-affective configurations emerging between this generation of women and men (Del Valle, 2002, Gil & Vall-llovera, 2009). In turn, the aforementioned comment can be read as a clarification in response to the “hegemonic masculinity” (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005) of his friends, in the sense that the heterosexual male usually associates intimacy with sexuality. This, in numerous occasions, is reinforced by the group of peers, who comment on the “suspicious” relationship maintained by the “best” mixed ones. In effect, such relationships generate discomfort among various groups of adolescents and adults, who fail to decode them and therefore sometimes question them.

In another observed example, a young woman (17 years old) comments on an idyllic outing with her boyfriend (“we went to Shopping Abasto, ate at McDonald’s and bought clothes”), although in reality she refers to her “best” friend. These status updates are common among the adolescents in the sample, who display an ironic discourse towards the heteronormative model. Although it is initially a link that does not usually include sex-affectivity, several adolescents update their states expressing the desire to have a boyfriend who is also their “best”, or thanking their partner to be their “best”.

In sum, “the best” and “the best” represent a specific phenomenon among these adolescents, closely linked to the “endurance” component in affective terms. In this orbit of contacts, a greater affective expressiveness of males is also visible, particularly in affection publications from “the best” to “the best”, or from a male to his partner. In most cases, intimates have a fundamental copresential dimension, which is strengthened by online interaction.

Everyday group

With “daily group” alludes to the close and copresencial pairs, with whom spaces like the neighborhood, the school, the “corner” and the soccer field are shared. Between these contacts a constant “round trip” of offline and online interactions is displayed. In this orbit the following components are present: shared spaces and history in common.

Whenever we can, we walk on Face with my friends. I’m more with them than with my own family. They are my “ranchada”. At times more than my family. Then when you put yourself in a couple and form your own family you do not look so much anymore (woman, 16 years old, low-income sectors).

In this type of contacts, as in the others, the “I like” is the main interaction. Users usually have three reasons to use it: empathy, sympathy and coincidence or identification: “I like when I like what I see or read, when it identifies me or moves me” (Woman, 17 years old); “I like when I feel like it because it made me laugh, I was happy or I liked what was published” (Woman, 18 years old); “If it happened to me or what someone posts, or if I would like it to happen to me, I like it” (Male, 15 years old). Likewise, the exchange of likes reveals a central feature in the interaction in Facebook: the overlapping of the playful-voyeuristic activity as a supposedly altruistic gift, with the aim of making each intervention in the network a strategic presentation of oneself.

In this line, as developed in another work (Linne, 2015), the intimacy performances that each user performs can be framed within a premeditated strategy of seeking popularity and social success among their different types of contacts, as well as trying to achieve a satisfying sexafectivity through seducing an audience as wide as possible (but controlled) through interactions in the network. In this sense, the concept of “multimity” is proposed to account for the fact that publications between adolescent peers in the social network are part of calculated and rational socio-communicative strategies, which only show certain aspects of personal and peer group intimacy. In contrast, in a well-known essay, Sibilia (2008) states that young generations live in a contemporary “extimacy”, preoccupied with showing themselves and obtaining the greatest popularity at any cost by exposing their privacy in social networking sites.

Immersed in this “multimity”, whose main fuel is the like, the invisible “I do not like” -spoken in the silence or absence of feedback-, as well as the negative comments between everyday contacts (schoolmates, neighbors), generates forms of implicit aggressiveness. Its consequence is, at times, explicit violence, both digital and copresential: fights, cyberbullying, monitoring, “escraches” and “ruining walls.”

The fragments of interviews also provide evidence to the analysis proposed: the daily group builds its bonds of friendship in a constant offline-online continuum. Likewise, this second orbit of contacts performs voyeurism and displays searches of sex-affective relationships in a joint way. For the maintenance of these daily relationships between peers, chat, private messages, suggesting contacts and being mentioned in the publications of others are key.

In addition, it is observed that adolescents from low-income sectors usually intensify their interactions by means of Facebook. It is possible to affirm that this same circuit is the “social fact” that leads them to participate in it on a daily basis. According to different researches (boyd, 2008, Morduchowicz, 2012), the main reason for adolescents to use Facebook is to be in contact with their intimate and daily friendships. That is, to extend the time of sociability between peers beyond school time and the copresential meetings in clubs, in the public space, in homes and in other institutions.

Extended group

This orbit, located in an intermediate zone between everyday and unknown people, is made up of known contacts: neighbors, companions and friendships in common. They tend to be known and have a copresential or pre-existing link to that of Facebook, or copresential references of friendships in common. If the basic function of the unknown contacts, as developed in the next point, is to contribute to personal and site statistics; that of the extended group is constantly feeding the flow of sociability. In this orbit the following components are present: shared spaces and history in common.

Extended contacts provide a significant contribution to sex-affective sociability (real, imaginary or potential). As pointed out by different researches (boyd & Ellison, 2008, López & Ciuffoli, 2012), Friendster was the first social networking site to be based on the principle that among friends-of-friends -i.e., among the extended group of peers- better couples would be formed than among strangers. This was one of the basic principles taken up by Facebook and placed at the center of its architecture. Unlike among strangers, among friends-of-friends there is usually a greater degree of common components to generate links.

See you at school, we play soccer, we go out, we get together to do tournaments with Play [station] and we chat for Face while we look for girls. There we advise on the candidates through chat or inbox or when we see each other (Male, 17 years old, low-income sectors).

The extended group provides each other with likes and voyeurism, as well as expanding the resources to add “popularity” and look for both friendship and sex-affective relationships. To this orbit of contacts are directed the strategies deployed among adolescents of sp to extend sociability. To extend your radio interactions on the site, for example, promise a list of “the 15 most beautiful and partible” of your Facebook or give the phone number in exchange for a “like”.

Unknown contacts

In this orbit, the most extensive of the four proposed here, there tend to be fewer interactions. According to the adolescents surveyed, in order to add a contact to this orbit, the main requirement is to share common contacts. In other words, if you do not know it but have contacts in common, you usually choose to add it, since you trust that it is part of your extended network: “I accept them even if they are unknown, if only to be friends. As long as they have pictures and their friends speak to them; if not, it is false “(Woman, 14 years old, sp).

I accept strangers when I want to add friends. I already have 1 200. Total later, if they bother a lot, I erase them. Sometimes some publish things that are good (Male, 18 years old, low-income sectors).

I do not accept anyone unknown. Only friends and sometimes friends of friends. But I have to know well who are friends. I heard from people those who persecuted or robbed them for accepting strangers (Woman, 14 years old, low-income sectors).

Through this broad orbit, the teenagers of sp exchange entertainment and voyeurism, looking at other people’s publications and profiles about the daily activities and biographical data of other users. It also serves to extend the network, exchange resources and comments to add popularity, as well as to have more possibilities of friendships and sex-affective ties.

This group is the basis of sociability in Facebook and forms the interconnected networks of “invisible prosumers”,6 in the sense that they enrich the news column of a profile. It is worth remembering that, according to the architecture of the site, the maximum number of contacts allowed is 5 000. It is common for teenagers to update their states complaining that they have hundreds of online contacts (available to chat) and none of them communicate with it or she.

On the other hand, the sample shows that those who most add strangers are singles, who usually look for potential sex-affective bonds. This need for feedback implies the constant search for new contacts in order to obtain a high number of likes and comments in their publications. At the component level, they only have in common a shared space, that of Facebook.

Conclusions

This article addresses the types of friendship established by teenagers from Buenos Aires popular sectors on Facebook. Among their main contributions is empirical evidence to argue that they do not build a homogenous and indiscriminate friendship in the social network, but they know how to distinguish between different types of friendship. However, this does not eliminate the various conflicts: from jealousy and monitoring to popularity competitions. In the ecosystem of like and constant feedback, different tensions occur around sexaffectivity and the search for social recognition. Why did not he answer me? Why do I have so few “likes” and comments? Why, being male, I can not have a better female friend?, or vice versa.

The virtual ethnography had two main stages. In the first place, an ad hoc profile was managed in Facebook and components common to the friendships managed by this group of adolescents were explored. Second, the publications were classified into four groups according to the components they shared: “shared spaces”, “stories” in common”, “affectivity “and “endurance.” From the above, four types of friendship observed in their interactions both online and offline are proposed: 1) the intimate, whose function is to provide affective support, support, “endurance”, accompany and advise through copresential encounters and online interactions; 2) the daily ones, which are usually defined as close pairs whose purpose is to provide voyeurism and safer search of sex-affective relationships and reliable contacts; 3) extended ones, which are usually friends of friends, and their function is to extend the flows of sociability and “popularity”; in addition to providing likes and greater amplitude in the search of sex-affective relationships; Finally, 4) the unknown, which would be the zero degree of friendship, although they represent the basis of sociability in Facebook, because they allow to increase the number of contacts and expand possibilities of sociability. 5 000 friends? Well, no, a dozen friends and a large space to experience the identity construction itself in different orbits of contacts.

Here, empirical evidence is provided to show that “friendship” and online sociability among adolescents is not homogeneous or indiscriminate, but differs according to the types of links they display in their offline-online daily life. In this sense, four analytical contact categories are proposed according to the degree of intimacy and shared friendship: “unknown”, “extended”, “daily” and “intimate”. With the concept of “multimity” we pretend to realize that the adolescents of Buenos Aires do not share their intimacy with everyone in a completely spontaneous way; this operation also includes calculated strategies: they target a small group and perform intimate performances with which they present themselves, in the best possible way, to their community of contacts in Facebook. With the native categories of “the best”, this population of low-income sectors refers to the solid bonds of “endurance” and unconditionality implied by these intimate friendships. The “ranchada” alludes to that intimate friendships operate as a second home built, as a refuge and group of main reference in the face of the constant conflicts and precariousness of the family institution that they often suffer. At the same time, it implies a more accurate representation that for teenagers from low-income sectors not all friendships in Facebook mean the same thing. Indeed, as described throughout the article, they clearly distinguish the different types of links they have among their network of contacts.

REFERENCES

Alabarces, P., & Rodríguez, M. (Comps.). (2008). Resistencias y mediaciones: estudios sobre cultura popular. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Assunção, R., & Matos, P. (2014). Perspetivas dos adolescentes sobre o uso do Facebook: um estudo qualitativo. Psicologia em Estudo, 19(3), 539-547. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-73722133716 [ Links ]

Auyero, J., & Berti, M. (2013). La violencia en los márgenes. Buenos Aires: Katz. [ Links ]

Boyd, D. (2014). It’s Complicated. The Social Lives of Networked Teens. Londres/New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Boyd, D., & Ellison, N. (2008). Social Network Sites: Definition, History and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230. DOI: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x [ Links ]

Capriati, A. (2014). “Una aventura abierta”. Acontecimientos biográficos de jóvenes residentes en villas y barrios populares del Gran Buenos Aires, Argentina. Última Década, 22(40), 109-129. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22362014000100006 [ Links ]

Connell, R., & Messerschmidt, J. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity. Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829-859. DOI: 10.1177/0891243205278639 [ Links ]

Del Valle, T. (Coord.). (2002). Modelos emergentes en los sistemas y las relaciones de género. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

García Canclini, N., Cruces, F., & Urteaga, M. (Coords.). (2012). Jóvenes, culturas urbanas y redes digitales. Madrid: Ariel/Fundación Telefónica. [ Links ]

Gil, A., & Vall-llovera, M. (2009). Género, TIC y videojuegos. Barcelona: Editorial de la Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. [ Links ]

Haythornwaite, C. (2005). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects. Information, Communication & Society, 8(2), 125-147. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180500146185 [ Links ]

Hine, C. (2012). The Internet: Understanding Qualitative Research. Nueva York: Oxford [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo-INDEC. (2012). Encuesta nacional sobre el acceso y uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC). Ciudad de Buenos Aires: INDEC. [ Links ]

Kessler, G., & Dimarco, S. (2013). Jóvenes, policía y estigmatización territorial en la periferia de Buenos Aires. Espacio abierto, 22, 221-243 Recuperado de http://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/espacio/article/view/17691 [ Links ]

Krauskopf, D. (2000). Dimensiones críticas en la participación social de las juventudes. En S. Balardini (Coord.), La participación social y política de los jóvenes en el horizonte del nuevo siglo (pp. 119-134). Buenos Aires: Clacso-Asdi. [ Links ]

Linne, J. (2016). La “multimidad”: performances íntimas en Facebook de adolescentes de Buenos Aires. Estudios Sociológicos, 34(100), 65-84. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24201/es.2016v34n100.1389 [ Links ]

López, G., & Ciuffoli, C. (2012). Facebook es el mensaje. Oralidad, escritura y después. Buenos Aires: La Crujía. [ Links ]

Margulis, M., & Urresti, M. (1996). La juventud es más que una palabra. En M. Margulis (Ed.), La juventud es más que una palabra (pp. 13-30). Buenos Aires: Biblos. [ Links ]

Merklen, D. (2005). Pobres ciudadanos. Las clases populares en la era democrática (Argentina, 1983-2003). Buenos Aires: Editorial Gorla. [ Links ]

Morduchowicz, R. (2012). Los adolescentes y las redes sociales. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Treviño, J. (2013). Cómo utilizar el análisis de redes sociales para temas de historia. Signos históricos, 15(29), 102-141. Recuperado de http://signoshistoricos.izt.uam.mx/index.php/SH/article/view/66 [ Links ]

Rosa, G., Santos, B., & Faleiros, V. (2016). Opacidade das fronteiras entre real e virtual na perspectiva dos usuários do Facebook. Psicologia USP, 27(2), 263-272. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-656420130026 [ Links ]

Sibilia, P. (2008). La intimidad como espectáculo. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Silba, M. (2009). El baile de las pibas, las piñas de los pibes (o viceversa). Sobre femineidades y masculinidades en jóvenes de sectores populares. En M. Chaves (Coord.), Estudio sobre juventudes en Argentina I. Hacia un estado del arte/2007 (pp. 167-197). La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata. [ Links ]

Simmel, G. (2002). Cuestiones fundamentales de sociología. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Urresti, M. (2007). De la cultura del aguante a la cultura del reviente: cambios en la significación de la corporalidad en adolescentes y jóvenes de sectores populares. En M. Margulis, M. Urresti, & H. Lewin. Familia, hábitat y sexualidad en Buenos Aires. Investigaciones desde la dimensión cultural (pp. 281-292). Buenos Aires: Biblos. [ Links ]

Urresti, M. (2012). Las cuatro pantallas y las generaciones jóvenes. En A. Artopoulos (Coord.), La sociedad de las cuatro pantallas. Una mirada latinoamericana (pp. 3-29). Buenos Aires: Ariel. [ Links ]

Urresti, M., Linne, J., & Basile, D. (2016). Conexión total. Los jóvenes y la experiencia social en la era de la comunicación digital. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Universitario. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, J. (1997). Culturas juveniles, identidades transitorias. Jóvenes, revista de estudios sobre juventud, 1(3), 12-35. [ Links ]

Van Dijck, J. (2016). La cultura de la conectividad. Una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

2According to the Royal Spanish Academy, one of the meanings of “orbit” is “scope in which the influence of something or someone is perceived”.

3The “extended group” of acquaintances is related to what Haythornwaite (2005) calls “latent ties”, in reference to the fact that social networks (SRS) develop a continuous sociability between preexisting contacts and contacts of contacts, or acquaintances of acquaintances.

4With this expression, they refer to the fundamentals that are the links with these pairs as shelter, home, place of repair and affective-daily containment.

5This term refers to rules of conduct or digital etiquette that are not explicit in any regulation but that work among wide groups of Internet users. For example, they form part of the netiquette of diverse groups of users in Facebook, request permission from the other before labeling it, or not publishing photos or videos in situations that are compromised or unfavorable to their own image. Of course, not respecting the netiquette becomes conflicts.

6“Prosume” refers to the combination of production and consumption made by contemporary adolescents through ICT’s (boyd, 2014).

Received: July 19, 2017; Accepted: October 26, 2017

texto em

texto em