Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicación y sociedad

versão impressa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.30 Guadalajara Set./Dez. 2017

30th anniversary of Comunicación y Sociedad

Methodology flows from the Latin American South. The zone of Communication and Horizontal Methodologies

1Universidad de Guadalajara, México. Correo electrónico: corona.berkin@gmail.com

In this article, turning the map around implies redesigning representations of power. Reversing the traditional vision of flows of thought, situating communication and culture research in another way, brings into view a set of studies coming from the South, giving form to a Latin American thought developing its own theories and methodologies. This article updates the history of Latin American theory flows, based upon Horizontal Methods for building new knowledge in Communication and Culture.

Keywords: Methods from the South; Latin American Communication; Horizontal Methods

En este artículo, dar vuelta al mapa implica rediseñar las representaciones del poder. Invertir la tradicional visión de los flujos de pensamiento para colocar, de otro modo, la investigación en comunicación y cultura, visibiliza un conjunto de investigaciones que vienen del Sur y que han dado forma a un pensamiento latinoamericano que desarrolla sus propias teorías y metodologías. La historia de los flujos de las teorías latinoamericanas se actualiza en este artículo, en los Métodos Horizontales como propuesta para construir nuevo conocimiento en Comunicación y cultura.

Palabras clave: Métodos del Sur; Comunicación latinoamericana; Metodologías Horizontales

A few days ago I came upon a phrase that caught my attention: “Nothing about us, without us”. It was the title of a book, referring to a slogan used by the 1970s movement in Berkeley, California toward independent living for disabled people: they were protesting against that era’s welfare-based and paternalist policies. Interested in the way they expressed their demand, I found that it was first used publicly in Hungary in the XIX century, to hotly contest reconfiguration of foreign policy in the region of Central Europe. But the original Latin expression, "Nihil de nobis, sine nobis", is much earlier, and was the cornerstone for governmental changes in XV century Europe as authority transferred from monarch to parliament, from individual authority to the voice of the people.

I relate this anecdote now because it sparks a series of questions regarding what we actually do in Latin American universities, with the research studies we undertake, the methodologies we employ, and above all the results we achieve. The horizontal methodologies to which this article refers relate to this quote in two ways: in its call for including the voices of those being spoken of, and secondly, with its implicit political content, where those speaking out for themselves construct the necessary knowledge for coexistence in the public sphere.

In this section I present methodological flows from the South during the sixties and seventies, as antecedents to horizontal methodology. I will mention the impact of theories and methodologies migrating from the north as well as those from the South, since some of these arrived with different aims, and exert influence, however unequal, upon what we study today as social communication.

For Martín-Barbero (1982) there was a trap within research conducted during those years in Latin America, dealing with the act of “doing theory” being seen as something suspicious:

From the right, because devising theory is a luxury reserved for rich countries and our lot is to apply and consume. From the left, because “real” problems, the brutality and urgency of situations, offer neither the right to theorize nor the time. And yet theory is one of the key areas of dependency … But dependency consists not in assuming theories produced “elsewhere”; what is dependent is the very concept of science, of scientific work and its function in society. As in other fields, the most serious thing here is also that products are not exogenous themselves, but rather the very structures of production are (p. 110).

Martín-Barbero is referring to so-called conservative positions, which clearly consider doing theory as apt only for northern countries. Important functionaries in communication were convinced that development in Latin America would come from application of U.S. theories: “We are too poor for theoretical speculation, as is done in Europe ... We are too poor to indulge ourselves in seeking theory after theory” (Beltrán in Solís, 2016, p. 59). Even today we may observe an overwhelming tendency to base Latin American studies upon an exogenous bibliography.2 This may be because it is still thought that generating an “autochthonic theory” is troublesome to achieve, and that the best Latin American offerings in social science have been creative syntheses of epistemological, theoretic-methodological and even technical elements, of diverse origins, with elements generated locally ...” (Sánchez Ruíz, 2016, p. 6). Here I aim to show the theoretical path blazed from the South, showing that immobilization of communication theories and methodologies only happened in the realm of “administrative” proposals. Both the power of criticism, and its absence, control the methods and results of a science “with scientific criteria”, which, always conducted with the same methods and hypotheses, yield similar results; this fails not only in furthering knowledge, but in responding to new problems. According to Sassen, one of the traps of endogeneity is to create an explanation for phenomenon X which at the same time prevents seeing not-X (Sassen, 2010). New knowledge is more complex than institutionalized theories from the north will have us understand.

Reflecting upon the theory-reality relationship through Horizontal Methodologies has led me to place in the bibliography those flows of ideas, theories, practices, methods, and even social movements impacting the way we think of communication in Latin America, and particularly in Mexico.

Some authors seeking to institutionalize the field are concerned for its consolidation as to agreement about the definition of the concept of communication (Fuentes, 2013; Sánchez Ruiz, 2015; Vidales, 2013), and this search for coherence is mainly carried out through theories in vogue in the north, but having less to do with Latin American-generated theoretical structures. Nor is segmentation a problem, to the contrary, fragmentation of fields of study is nothing new; there have always been multiple routes for thinking of human and social phenomena. Thanks to this diversity, knowledge has developed along many paths, some more rewarding than others. To think of an era when scientific research was ordered, unified, monologic, is simply nostalgia for something that never existed. In other words, the diversity of knowledge is “instead of a deficit, its distinctive quality” (Guber, 2001, p. 56).

But we also find those who consider that, as the field develops and fragments, the majority of social studies are related to other disciplines (Cornejo, 2007). They may also recognize that not since the beginning of communication has there arisen any autonomous field, simply subsystems of social function; in other words, that “the field Schramm built consisted of leftovers from previous research, paired up with such dispossessed fields as academic journalism, drama or speech” (Durham Peters in Fuentes, 2013, p. 390). Thus a large part of the communication research done in the world borrows concepts from various disciplines, with just a few overused words for naming reality, or again as Durham Peters states: “Nobody believes any longer in emissions and receptors, channels and messages, noise and redundancy, but these terms have come to be part of the basic structure of the field, in textbooks, course descriptions and bibliographic reviews” (Durham Peters in Fuentes, 2013, p. 390). In other words, by repetition, certain concepts have wound up naming the world of communication, and all that cannot be pigeonholed with those labels remains occult, invisible, irreconcilable.

Still, navigating the borders of a discipline (in the strongest sense of the term discipline) disposes one to greater opportunities for being creative (Cornejo & Guerrero, 2011), and producing new knowledge. Breaking through the wall of invisibility for communication research with studies that are more political and critical, and proper to Latin America, is another proposal (De la Peza, 2011). Aligning my own research with Horizontal Methodologies (Corona Berkin & Kaltmeier, 2012), has led me to locate other flows of ideas, theories, practices and methods coming from the South and north, with different effects upon what we think about communication.

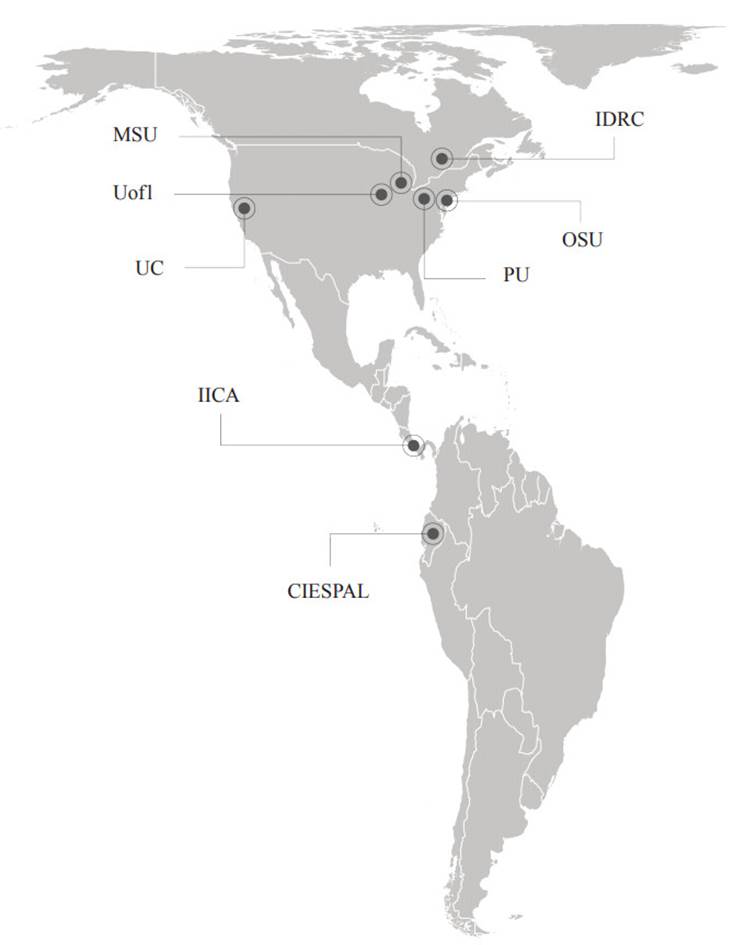

At this point I share my notes for creating a map of the theoretic-methodological flows from the sixties and seventies, those going from north to South and also from South to north, aiming to show the relevance of the above theories and demonstrating how inexact it is to think of them as simple applications of, or as empirical studies to nurture, research conceived in the north. The historic overview in these “flow maps” is thus relevant for today’s research in communication, whose challenges include understanding social compositions and their communicative referents in the Latin American South within a new context of violence, dependency, excluded political configurations, marginalized sectors, cultural diversity, etc. In the maps of the South I take more care to locate the impact and its influence upon what I call Horizontal Methodologies.

One more clarification: in the flow routes I use the Peters projection and not the better-known Mercator, since the former skews scale less and represents it as much closer to geographical reality. The Peters projection mathematically corrects distortion of northern latitudes, while the Mercator exaggerates the size of lands in the north. This representation, while used in basic education programs and textbooks in Latin America, magnifies Europe and North America and with that disproportion promotes a Eurocentric, Western view of the world. By approaching actual representation with Peters we may observe that the north is in reality smaller, which is why from here on, in line with this map and our objective of bringing to light research for the South, we will call it “the little north” when flow starts from there, and speak of the South or Latin America when referring to the American continent from the Río Bravo to Tierra del Fuego.

Maps from the little north to the South, and from the South to the little north

I begin with several geographic locations showing exceptional production of communication research, which is not to mean that creative work hasn’t been done in other areas of the little north and South, but that simply by not being part of the hegemonic research, they cannot be found in the bibliography I have been able to consult. One current pending concern is to find those researches that, with neither budget nor publicity, have impacted the knowledge that generates better conditions for social coexistence.

While the title indicates priority as given to research in communication, the following references and discussions have to do in large part with sociology, since communication began as an area reflecting the social field. Along the way I recognize the names of those who participated as agents of theoretical migration from the little north to the South and later from the South to the little north. This does not aim to be a story of people, but of flows of collective ideas, so the bearers are not “authors” in the sense that Foucault gives to intellectual production as never individual; the names of people simply help us establish the route that theoretical models follow from one zone to another. The maps make mention of concepts or labels used in each case to recognize social phenomena within communication; the objectives of the centers for propagating research, whether institutionalized groupings or conjunctural associations; the methodological techniques employed, and the nods to theory in each place. Secondly, with the objective of entering this theoretic-methodological proposal into the genealogy of social research that opted to think differently of communication when facing the acritical ways of the little north, I compare three ways of doing research in social and cultural sciences corresponding to maps of the little north and the South: science with “scientific criteria”, action-research and horizontal methods.3

Flows from the little north to the South

We have seen the theoretic-methodological flow for communication research from the sixties and seventies on the American continent developing two major perspectives: the structural functionalist accompanied by quantitative techniques for empirical data gathering and measurement, which (above all in the United States) followed scientific criteria and concerned itself with social aspects of development and modernization. The second was the critical model linked to academic Marxism and to the structuralist Marxism of Althusser and Poulantzas. Here the predominant topic was dependent capitalism and routes toward Socialism, as well as the emergence of popular social classes. A third model that wasn’t exclusively identified with either of the above two was known as historic-structural. On the other hand, the theme of social transformation motivated a reestablishment of field research, and development of subject fields such as culture, communication and social praxis.

Historical contexts had an impact upon research development, developing in different ways in each country, raising interest in tracking particularities and links between theoretical reflection and field work, the objective of specializing researchers (for teaching, research, applied studies), demand for results from the State, the growth of international organizations (UNESCO, Ford Foundation), national and international associations and meetings, etc.

Adopting theories from the little north is seen as a prescription for development and progress. The attraction exerted by models of development known at the time as “centrally planned economy”, and the launching of the Alliance for Progress by the United States, impacted research, with such objectives as rural support and training, promotion of health and hygiene and family planning framed by development agencies. Still, concepts and models of communication imported from the United States had other initial objectives: strengthening its own system with technological research in times of war, and extending its markets in times of peace. Reproducing these models in Latin America within a context of theoretical subversion only helps prolong the situation of dependency which in many cases is still being replicated in programs run by schools of communication.

U.S. theories began arriving in the fifties along with U.S. and Canadian university students and functionaries, and international cooperation agencies offering all sorts of scholarships to study in the United States. On the other hand, Latin American research in the South is linked to the exodus and migration of intellectuals from the South to Mexico in the seventies, as they fled military dictatorships. This marks a critical path for many researches that defied the scientific hegemony of North American functionalism in the sixties.

With the seventies, university students were trained according to the goals and methods offered by CIESPAL:

To measure Latin American reality through: opinion surveys, measuring attitudes, behavior of rural communities, television’s influence on students, mass attitudes toward international events, overcoming such anomic conduct as alcoholism, delinquency and anti-establishment political attitudes (Villagrán in Jiménez, 1984, p. 66).

The CIESAL proposal was criticized for promoting traditional models for shaping labor to the market and strengthening dominant mass media norms.

Flows from the South to the little north

Flipping the map implies redesigning the representations of power. Reversing the traditional view of the world and flows of thought to set them another direction, this time from the south to the little north, brings to light a set of researches that have shaped a Latin American thought that develops its own theories and methodologies. These theories and methodologies are clearly fed by the best of human thought, but as Martín-Barbero states: “Latin America is not a mere-object-of-study but rather the-place-from-where-one-thinks” (personal communication). In short, Latin American thought is a way of knowing, taking into account the flow of models from other parts of the world, but when put into practice within Latin America’s political, economic and social contexts, and in light of our social realities, not always explaining social fact. To think of Latin America from the Latin American South means producing theories and methodologies that allow to grasp this reality.

There are three concepts present in this map: Criticism of imperialism: Subversion as reconstructive of society, liberation from political, economic and ideological domination by developed capitalist countries. Communication and development. The Theory of Dependency: born in the south, contributed terms for thinking of communication in relation to the little north, where domination and colonialism are read for the first time in terms of the dominance relationship and not the situation of underdevelopment. Popular communication is defined as:

A methodological option offering possibilities for true integration of people and researchers, knowing and transforming their reality and thus achieving their liberation … Managing to understand that authentic development is an endogenous process of the people (from base groups) themselves, since it is they who carry it out, and here participatory research acquires its importance, as a viable promotional medium or instrument (Vejarano, 1983, p. 9).

In this context, the aim was to overcome the U.S. model by which communication was studied until then. Against preoccupation with the effects of passivity and violence proper to the inherited models themselves and their Latin American applications, the new research denounced ideological capital and the dependency situation.

A particular scenario may be observed as addressing the work of women researchers in the South for the importance their distinct perspectives had on thinking about dependency and domination with consumer as agent; as differentiated from proposals being set forth at the time.

Also meriting special attention is the role of the church, above all the Jesuits, in founding schools of communication in Brazil, Chile, Argentina and Mexico (Trindade, 2007, p. 40). The expression of the post-conciliar church and the theology of liberation are processes that provide a very specific context for communication research and its relation with politics.

Another important proposal for theories of the South was the ongoing discussion and criticism occurring in various Latin Americans institutions and departments. In the seventies, Latin American theoretical argument (and its communicative particularity) appeared in: Sociedad y Desarrollo journal (CESO in Chile), Sociedad y Política (Quijano in Peru), Cuadernos de la Realidad Nacional (CEREN in Chile), Communición y Cultura (Mattelart and Schmucler in Chile, Argentina and Mexico), Arte, Sociedad e Ideología (in Mexico), and Chasqui (UNESCO-CIESPAL in Ecuador); this last, a journalistic review, disseminating Latin American experience. The context of theoretical debate for generating questions about communication involved ideology, imperialism, capitalism, dependency; as opposed to the functionalist context from the little north, where various forms of social knowledge were kept under wraps.

A question arises from these maps: What do we lose when covering up theoretical arguments generated in Latin America regarding communication? Responses are many, and require special case-by-case answers. Still, we may advance the point that reducing communication to models and opposing so-called essays with “scientific criteria” research, favors standardized knowledge from the little north. The essay genre, a long Latin American tradition, has the advantage of variously exposing social analyses, as it is not based in homogenous models. Essays provide new “words” for thinking, against labels determined by theories with universal pretensions. The wide overview that takes into account cultures, governmental models, ideologies, criticism of technology, reasons held by others, languages defining communication, etc. is rarely considered in today’s research, which is generally a prolongation of standardized research from the little north. In the flow that puts an end to diversity, we also weaken individual identity, critical thought, new ideas, and the capacity to resist; as happens with languages, when one is lost, we lose a way of knowing the world.

While the Latin American academic struggle was displaced to official international organisms like CIESPAL and private media organizations opposed criticism and NWICO, what endured had been learned from the South: with different approaches, postcolonial studies today speak of subordination and the struggle for one’s own vision within the situation of colonization.4 Insisting upon one or the other aspect, Marxist and Gramscian theoretical arguments had their impact in the trenches. Some professors and students trained in this line of battle suggested other ways to effect social changes, joining unions and non-government organizations and producing alternative forms of communication with new artistic, cultural and political perspectives. To focus on one case for its impact on indigenous politics in Mexico and its international repercussions, the Zapatista National Liberation Movement, founded in 1974 and reaching the Mexican jungle in 1984, resonated in speeches circulating during this era, denouncing the fight to impose just one vision upon the world. The uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army on January 1st, 1994 made indigenous movements visible, and is another sign of a continuous line of demands for their own vision of the world. From this theoretical genealogy Horizontal Methodologies arose. The legacy of research done in the South, which itself was influenced by theories of language, Gramscian Marxism and the School of Frankfurt, generated a position where otherness should be included in social research, making problematic the unique, monolithic, hegemonic vision and building new knowledge in the cultural and social sciences. Thenceforth HM found departure points for arriving at different models for thinking and generating knowledge for living in public space.

In other words, faced with those who think there are no new theories because “we are in the presence of societies that appear not to have a central problem from which to construct a model” (Trindade, 2007, p. 52), we find that the central problem does exist, and it is the political coexistence of all the others that we are, irrevocably lost from focus and “resolved” with repressive, arbitrary and authoritative governments. The model to which we refer is that of Horizontal Methodologies, which, schematically summarized below, is a research practice for building new knowledge from equitable discourse, in the process creating autonomy for voices requiring social coexistence.

It remains to be noted that all methodology derives from an epistemological construct. Horizontal Methodologies are no exception: while we know singular truth to be a falsehood, objectivity to be impossible and the researcher/researched relation to be one of domination, it is difficult to find research that formulates new epistemological routes. What is presented below is not a research technique, but a method involving a theory of knowledge, of conditions and modalities, always dialogic, for building knowledge; not dealing with reflexivity, collaboration, construction, but with the new doors that horizontality opens to new knowledge.

Horizontal Methodologies

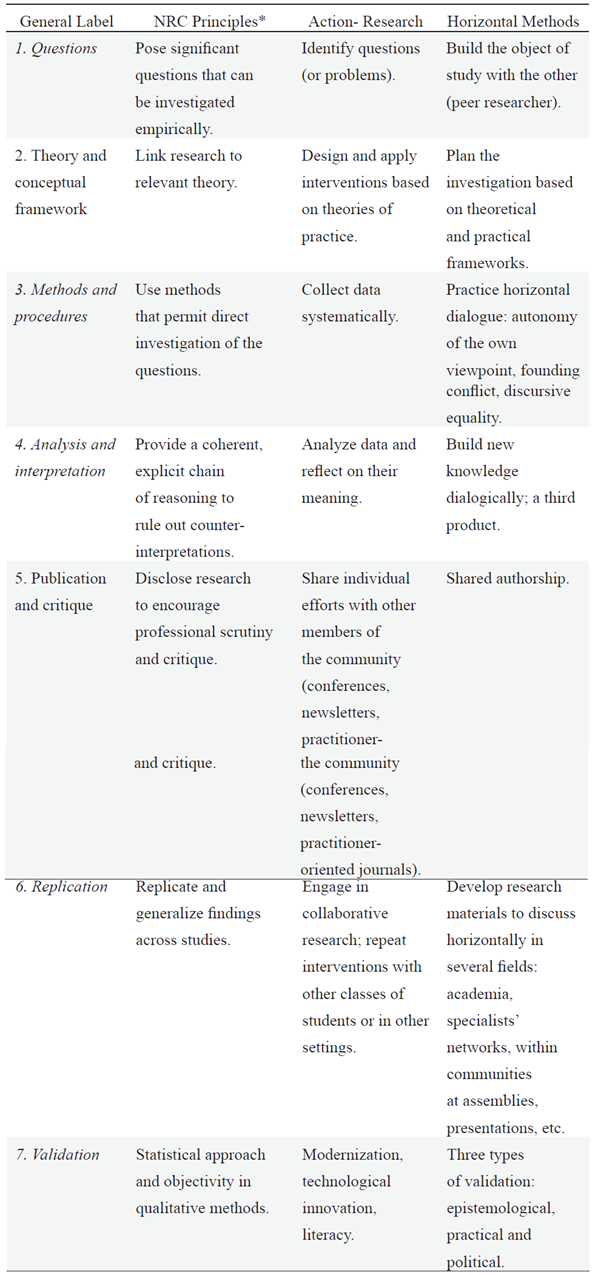

In this comparative chart of seven categories, three principal (and current) theoretic-methodological perspectives for researching communication stand out.5 Differences are shown between the perspective of scientific criteria (SC) in research carried out by the U.S. National Research Council (NRC), those defining collaborative-participative research as practiced in that country and Latin America, and finally the general description of horizontal research that we have employed with Latin American and German colleagues (Corona Berkin & Kaltmeier, 2012). The source of the first six categories and two columns, is based upon the NRC (De Ibarrola & Anderson, 2014), there I add the third column referring to Horizontal Methodologies. The seventh category of Validation is of my own devising and refers to standards by which each form of research defines results as rigorously scientific. As this section’s central object I compare Horizontal Methodologies with other methodological approaches to communicative phenomena.

Table 3

* Basic scientific principles in research by the National Research Council (NRC) of the United States, in De Ibarrola and Anderson (2014).

Source: Own elaboration.

Questions

From a horizontal perspective, questions do not respond to needs previously determined by the researcher, but are built by a team of researcher and peer-researcher (as opposed to those called “informant” or “subject of study”), identifying in praxis that which both consider crucial and in need of knowing, given what each knows.6

We are not dealing here with the right to speak held by all citizens in the public sphere when facing a series of interactions with social actors and groups, ever more complex and diverse, for arriving at accords marked by respect and understanding between participants. In the case of research with Horizontal Methodologies, achieving an interaction generative of new knowledge means dialogue along horizontal lines with the peer-researcher, for creating together a new explicative discourse for social phenomena. In public space we exist only in communication with the other, and without “words” to name ourselves, we have no place to exist -perhaps just labels to establish hierarchy and domination-. This fact obliges the researcher in communication to dialogue with a peer-researcher so that the knowledge each has exists, as does their respective ignorance. When research is undertaken with the other and not about the other, the question of the academic investigator is renewed, recalled, modified and structured along with the peer-researcher.

Theory and Conceptual framework

The proposal of Horizontal Methodologies is based upon theory and practice being part of the same process, and the point that theoretical concepts don’t necessarily precede practice nor determine its content. It is revealing that a principle of scientific Eurocentrism should be theory conceived as abstraction separate from data, and that scientific knowing should be incompatible with production of knowledge out of everyday and traditional non-Western phenomena. Separating theory from praxis not only leads to difficulty in facing new political challenges, but also devalues other knowledge at the moment of distinguishing what is science and what isn’t, and generates hierarchies between one “who (legitimately) knows” and the other who “doesn’t know” but only acts. Research in Horizontal Methodologies is considered as an expression of the connection between the theories and practices of the researcher and the peer-researcher.

Methodologies and procedures

With the objective of setting forth methods and techniques for horizontal research, I have created several terms, among them: autonomy of one’s own viewpoint, generative conflict, and discursive equality.7

Autonomy of one’s own viewpoint. I argue that in order to know the other as they themselves wish to be known, the problem is not “having been there” sufficiently long to know them, nor is it drafting appropriate questions, even less is it “hiding (the researcher’s) true intent”. Autonomy of each respective viewpoint has to do with the dialogic event produced between researchers, where auditor and speaker take turns, translating themselves and each other in order to build knowledge of themselves and the other. In this sense, no one enters research with prior, essential or primal autonomy, but researcher and peer-researcher recognize themselves in the gaze that the other, horizontally, returns to them.

Generative conflict. All social research implies a conflict. But this, it is clear, may serve a civilizing purpose, when using horizontal methods achieves autonomy for one’s own view. I argue that demand and intervention are the conditions for creating ties of reciprocity and horizontality. First, the universe standardized prior to the researcher’s arrival, imagined as susceptible to “contamination”, is a universe that considers stories and rituals as primal and unaltered. From my perspective, to the contrary, cultures are not pure nor defined once and for all as a kind of original essence. Their stories are always dynamic. In horizontal research there are no pure indigenous epistemologies, nor is the objective to give voice to an “authentic” indigenous voice, but instead, through my intervention I seek to establish opportunities for discursive equality so that everyone is shown as they wish to be seen. This process I call “generative conflict”.

Intervention as generative conflict is political and has to do with putting the horizontal connection to the test, allowing one’s own needs and those of others to be expressed, facing conflicts and encountering new and negotiated ways of researching.

Discursive equality. Still, how is equality established from generative conflict? Equality is a central issue for devising Horizontal Methodologies. Not in vain is equality considered from multiple perspectives as a goal for the perfect communal life. It is clear that horizontal methodologies are not interested in equality that fades out, or mutes differences, but rather sees equality as a condition for expressing them. In the methodology proposed by Horizontal Methodologies, from a connection created by explicitly exposing the objectives and needs of those involved, there appears a possibility that my intervention may result in autonomy for the voices themselves.

Analysis and interpretation.

Horizontality means that two or more subjects participate in the dialogue, with their own voices and motives. With respect to this, Bajtin (2003) notes that the function of the other is social, simply because the subject is a dialogic phenomenon in which the other is a constitutive part of being; in Horizontal Methodologies the peer-researcher is constitutive to the academic researcher.

Constructing oneself while facing the other puts in question the possibility of knowing the other without their own participation. From this perspective, what may be known is just that which the other wishes to be, during the research encounter. Thus the importance of building horizontal situations where dialogic analysis and interpretation do not exclude the contradictions generated at every turn, which provide input for creating new knowledge.

Publication and criticism

Authorship is part of the investigative process itself. The very construction of the object studied, its methods, concepts, techniques, etc., are generally authorship of the researcher. It is he or she who elects to construct the way in which research will be done, from theoretical concepts or from empirical experience. The researcher later becomes a translator and producer of explanations, from the stance that the other’s narratives are representations not spoken by themselves, and that interpretation is inevitable when building knowledge.

Given this practice, in Horizontal Methodologies authorship assumes discursive equality from the moment of framing the study proposal. Concepts and techniques arise from there. Generative conflict provokes the dialogue that team research produces. During the encounter, approaching the world of the other at the same time others are joining the sense-sphere of the researcher, builds communication between the two. Authorship of the research thus begins to happen in various voices. Objectives, goals and techniques are all negotiated.

No genre for writing “among voices” exists as such; however, while unresolved, what are being formulated are editorial design, multiple texts produced in the process of horizontal research, and dialogue with other material such as photographs, maps, drawings and letters. The form, content and horizontal characteristics of the process determine what the finished product says.

Reproduction

While expression by the voices of all involved in the research interests me, I realize that there is not just one discourse for a vision of the world: there are those by family, generations, ideologies, each offering another response but also having one’s own response and the voice of the community. The product of Horizontal Methodologies does not aim to be one and homogeneous, nor one hybrid, but instead multiple and historicized, where it may be observed that the voice of one is always determined by the voice of the other. Research must consider all links possible for creating knowledge of how to live better in community, connecting them in a horizontal plane and abandoning all pretense of universalizing or owning the truth, accept it as fallible and provisional. Owing to its quantitative and qualitative complexity, the social act may only be addressed from its contextual character, meaning participation of those involved in terms of discursive equality. In this way we separate ourselves from theoretic-methodological proposals that claim to generate universal understanding.

Validation

The category “validation” does not appear in the original NRC chart, since according to its criteria science done with “scientific criteria” needs no validation. I however consider its absence as suggesting three traps, to be discussed in this section.

All methodology offers rules for producing the truth, establishing a relation between empirical evidence and knowledge-building. Various methodologies, while they may at first seem innocent, aiming to present themselves as simple instruments of objectivity, yet have epistemological, practical and political consequences. It is an impossible task to differentiate between these three, so intimately related to research, but for expository purposes I will speak of the three categories separately, identifying epistemological, practical and political traps in terms of horizontal research.

Epistemological traps. We know that disciplinary borders defend the type of evidence belonging to each discipline. After all, it is often thought that an academic cannot be expert in all areas, and must thus be restricted to certain aspects of the phenomena that a given discipline lays out.

Arguments like this are a way to evade the uncomfortable truth that if we want to truly understand social phenomena, multiple voices speaking on the same topic must be included. It is not a question of arguing with grand theories, but interrogating and transforming them with support from other rationales. If not thus, society will simply repeat the same problems that have been described in many research studies.

When very different voices from those of the “scientific criteria” sciences speak, with the same pretensions to truth and equality, the social sciences often have no room to accommodate them. Given the epistemological trap of Western science, knowledge proposed with Horizontal Methodologies is validated in other ways than under objectivity criteria. I propose as criteria discursive equality and authorship with others, set forth in the above section on method and procedure protocols.

The epistemological approach to research determines the possibility of producing new knowledge or repeating what’s already been credited. Epistemology is not reduced to reflection upon accumulated knowledge, but also upon the very process of production. Keeping in mind that methodologies are not innocent, and may become a way of eclipsing what is different, is one requirement for horizontal research.

Research practice trap. For the social sciences the fact of the human being as both subject and object of the research at the same time, is one of the central problems of scientific work. The practical trap is believing there to be ways of somehow knowing the other without their participation.

Social sciences, as controlled by academic institutions, take off from the supposition that creating distance between researcher and researched is a necessary requirement for knowing scientifically. In response, social sciences research manuals are full of instructions for achieving distance and preventing contamination of scientific production by researcher subjectivity.

My proposal, on the other hand, is to introduce and accept the social nature of subjects as a departure point; where each is always created facing the other, we commit to the postulate that others may not be known without their own participation. From our perspective, what may be known is only that which the other wishes to be known. Thus the importance during research of horizontal situations where both voices are raised in an equitable discursive context.

In social sciences, as regards the subject who knows (social scientist) and the object of knowledge (social reality), we may refer to that which Giménez (2004) puts forth:

The deictic property of social facts also involves important consequences for the testing regimen, which is to say for empirical validation. In effect, if in the social sciences we may resort not to empirical induction, nor experimental verification, nor to Popper’s cross-check strictly speaking, all that remains to us is the test by exemplification. But this is not to say that it is enough to pile up amorphous and disperse empirical comparisons, of zero probative value. We are dealing here with systematic and carefully-planned exemplifications, under high accountability standards (signifying rigorous methods for gathering, structuring and handling data) (p. 271).

In Horizontal Methodologies, rigor means considering the other, in terms of discursive equality, as involved in forming questions and data, even during its analysis and final authorship.

Giménez (2004) continues his discussion as to the impossibility of there existing any one general theory of society, given that this would prove unmanageable from a single theoretic-methodological perspective:

One of the most surprising facts in a contemporary revision of an epistemology of the social sciences has been that very appreciation for case studies, so devalued by the positivist-nomological conception of science, that only recognizes as scientific those researches based in wide samplings of large-sized populations. It is not insignificant that Scandinavian epistemologist Bent Flyvbjerg has dedicated a special chapter to the “power of example” in his stimulating book, Making Social Science Matter (p. 271).

Political traps. The political facet of research has to do with the horizontality of the process: either formally distinguished as “researchers” and “researched” -these last not considered fit for building scientific knowledge- or as I propose, laying out a road toward mutual knowledge where both are builders of what is known. The political research trap imposes legitimate rules of operation that leave out knowledge considered ordinary, eccentric or incompatible with its own frame of reference.

On the other hand, risks arise when making all participants in the research process equal, and the outcome may not be predicted at the outset. In Horizontal Methodologies, as in public space, in order to enable weaving new and different relationships between people, you need to renounce forecasting the ending at the start. What constitutes a true investigative space, as opposed to an ordinary “research protocol” that foresees results because they are built along roads already traveled, is that new intercultural knowledge is conflictive, strange, unknown and unforeseeable.

A final reflection will be made regarding political validation for research methods: it is imperative that these be transparent, and above all that they effect some sort of benefit for both parties. One of the effects of research, not collateral but essential, should be for horizontal investigative practice to promote autonomous viewpoints for all participants.

A provisional ending

On maps of flows from the little north to the South and from the South to the little north, we have observed Latin American thought regarding research in communication during the years of the sixties and seventies. However, neither from the little north nor from the South did pure theories arrive; they were pieced together from scraps, applied when migrating from one necessity to another.

I have presented these flows as antecedents of Horizontal Methods in order to highlight the political rationale for deciding not to research about the other, but with the other. We reflect upon ways of researching the other via so-called scientific criteria, which have eroded the moral realm for knowing the other, so it is clear today that we are not achieving hoped-for results from these supposedly generalizable methods.

There are still also researches done from collaboration and participation, where what directs the work is approaching the other to identify their needs and wants. While the value of “scientific criteria” science is to be true to oneself and one’s techniques, action-research is considered with generosity, as an obligation to its field of study and to the other.

But there are also Horizontal Methodologies which consist in forming common research issues by incorporating principles of equality, autonomy and emancipation. In Horizontal Methodoogies we aim to work from the conflicts generated by coexistence to build autonomy for voices and viewpoints, in order to create a new knowing with the other so scientific virtue becomes a political instrument for creating within the public space a better place to stand for everyone.

The maps I have presented as prior to a horizontal research project should be enlarged, their details developed, deep relationships disentangled, all theories visibly accentuated, older ones respecting Mother Earth taken into account; in other words, “academic territory” discovered in concert by many so each may exercise his or her right to be seen.

REFERENCES

Bajtín, M. (2003). Estética de la creación verbal. México, Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Cardoso, F.H. y Faletto, E. (1987). Dependencia y Desarrollo en América Latina. Ensayo de interpretación sociológica. México, DF: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Cornejo, I. (2007). El lugar de los encuentros. Comunicación y cultura en un centro comercial. México: Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

______ y Guerrero, M. (2011) Investigar la comunicación en el México de hoy. México: Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Corona, S. y Kaltmeier, O. (2012). En diálogo. Métodos horizontales en Ciencias Sociales y Culturales. México: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Corona, S. (2016). Diálogos educativos dentro y fuera del aula. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

______. y otras voces (2007). Entre voces. Fragmentos de educación “entrecultural”. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

De Ibarrola, M. y Anderson, L. (2014). The Nurturing of New Educational Researchers. Dialogues and Debates. Estados Unidos: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

De la Peza, C. (2011) “Los estudios de comunicación/cultura. Su potencialidad crítica y política” en Cornejo, I. y Guerrero, M. (coords.) Investigar la comunicación en el México de hoy. México: Universidad Iberoamericana , pp.21-55. [ Links ]

Guber, R. (2001) La etnografía: método, campo y reflexividad. Bogotá: Grupo editorial Norma. [ Links ]

Fuentes, R. (2013) “El campo académico de la comunicación en México”, en Valenzuela, J.M. (coord.), Los estudios culturales en México. México: Conaculta/FCE, pp. 380-419. [ Links ]

Giménez, G. (2004) “Pluralidad y unidad de las ciencias sociales”, en Estudios Sociológicos XXII: 65. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M. (1989) Video, tecnología y comunicación popular. Lima: IPAL/CIC. [ Links ]

Jiménez, J.H. (1984) La Ciencia de la Comunicación en América Latina. México, DF: Ed. Quinto Sol. [ Links ]

Martin Barbero, J. (1982) Comunicación y Cultura, No. 9. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Xochimilco. [ Links ]

Mac Bride, S. (1980), Un solo mundo, voces múltiples. Comunicación e información en nuestro tiempo. México DF; FCE/UNESCO. [ Links ]

Nethol, A. y Piccini, M. (1984) Introducción a la pedagogía de la comunicación. México DF: Terra Nova. [ Links ]

Pooley, J. y Park, D. (2014) “Communication Research” en The Handbook of Communication History. New York and London: Routledge, p.76-90. [ Links ]

Popper, K.R. (2008), “La lógica de las Ciencias Sociales”, en Popper, K.R. et al. La Lógica de las Ciencias Sociales. México: Colofón. [ Links ]

Sánchez Ruíz, E. (2016) "El pensamiento crítico latinoamericano sobre medios comunicación, en el contexto neoliberal: Un recuento autobiográfico", Conferencia impartida en el ICOM/ULEPICC 2015 La Habana, Cuba, 7-11 de Diciembre de 2015. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

Sassen, S. (2010) Territorio, autoridad y derechos. De los samblajes medievales a los ensamblajes globales. Buenos Aires: Katz Editores. [ Links ]

Solís, B. (2016) Comunicación: memorias de un campo. México, Tintable. [ Links ]

Trindade H. (2007) Las Ciencias Sociales en América Latina en perspectiva comparada. México: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Vejarano, G. (1983) La investigación participativa en AL. Pátzcuaro, Centro de Cooperación Regional para la Educación de Adultos en América Latina y El Caribe. [ Links ]

2 Pooley and Park (2014) studied a corpus of 1 600 published works explicitly described as being historical studies of research in communication. From this geographic analysis, the authors found that: the bibliography employed in these texts came from the United States and United Kingdom in over half the cases (55% or 906 entries), while those with bibliography coming from countries of the global South amounted to 4%, or 65 entries. As for individuals of prominence, 75% were of U.S. background. When added to western Europeans, the percentage rose to 95%. Only four names from the rest of the world were given any substantial treatment: Fanon, Ludovico Silva, Martín-Barbero and García-Canclini.

3I start from comparison as a basic exercise for cognitive activity. This model has been used since the XIX century in seeking to define Latin America’s own political models. The return to comparison arises in the second half of the XX century while advancing institutionalization of the social sciences, toward a better understanding of the problems proper to modernization and dependence. It is by comparing that we see that scientific activity is not reduced to a relation where the center determines what happens on the periphery (Cardoso & Faletto (1987), and in our case, nor does the “little north” determine all thought taking place in the South.

4“The works of Antonio Gramsci [were discovered] in the seventies, then quickly translated and disseminated in our country in the fervor of the Marxist atmosphere pervading the field of the social sciences. But the figure of Gramsci came to us filtered in large part by Italian demology, whose spokesperson, Alberto M. Cirese, was inarguably the initial spark and catalyst for cultural studies in our country. Our first seminar on popular culture in the Center for Research and Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS is its Spanish acronym), in July of 1979, sponsored by its then director Guillermo Bonfil, and the subsequent seminar given on the same topic at the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM-Xochimilco) in August, 1981, may be considered as important landmarks in the development of cultural studies in Mexico” (Giménez, 2004).

5As regards the scientific community, Popper considers that reproducing just one form of understanding a fact, goes against scientific knowledge: “the objectivity of science is not an individual matter for various scientists, but the social matter of its reciprocal critique, of the friend-enemy division of work among scientists, of their team work and also the work done respectively along different, even opposite, paths” (Popper, 2008, p. 25).

6“Knowledge begins not with perceptions or observations nor by recompiling data or facts, but with problems. There is no knowledge without problems -but neither is there a problem without knowledge … this begins with the tension between knowing and not knowing, knowledge and ignorance: no problem without knowledge, no problem without ignorance (Popper, 2008, p. 13).

7Terms developed in Corona Berkin and Kaltmeier (2012, pp. 91-97).

Received: May 12, 2017; Accepted: July 13, 2017

texto em

texto em