Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.29 Guadalajara may./ago. 2017

Articles

Transformations of a photographic poster exposed in a public space: some keys to rethinking the functioning of the media

1Universidad del Valle, Colombia.

This article presents the cycle of transformations experienced by a simple media -a photographic poster- over four months. By following and describing the changes of a photographic poster located in a public space, some interesting aspects are revealed. The situated and almost archaeological analysis of a simple medium reveals aspects about the functioning of the media frequently. Some of these aspects are ignored by theoretical representations and very general and static models of public communication.

Keywords: Media; situationist analysis; media archeology; public space; photographic poster

Este artículo expone el ciclo de transformaciones que experimenta un medio sencillo de comunicación -un cartel fotográfico- a lo largo de cuatro meses. Algunos aspectos interesantes se revelan al seguir y describir los cambios de un cartel fotográfico situado en un espacio público. El análisis situado y casi arqueológico de un medio sencillo revela aspectos sobre el funcionamiento de los medios de comunicación frecuentemente ignorados por representaciones teóricas y modelos muy generales y estáticos de la comunicación pública.

Palabras clave: Medios de comunicación; análisis situacionista; arqueología de medios; espacio público; cartel fotográfico

Presentation

Both, a small, simple medium -such as a stop sign on a public road- and those with greater technical complexity and industrial extension -a television channel- experience substantial transformations over time, that is, they are dynamic systems, in continuous variation and change due to the properties that emerge as a result of the interaction of the elements that make them up.2 This article examines some of the material transformations in an old, simple medium, a sign displayed on a wall. Examining these transformations allows inquiring about three key aspects: in what sense are the media complex systems of relations between human and non-human agents subjected to permanent variations over time?3 How can they be inserted within a preexisting media ecosystem? Given that no medium arrives in terra ignota; and to what extent are their senses not ensured at all? That is, they closely depend on the network of uses, appropriations and reading practices of those who live them and give them meaning, be it as users, as producers or as managers and administrators. The three questions are trivial and relatively obvious, but it is necessary to explain them to outline the set of arguments that I will develop in this article.4

Performing a detailed follow-up of the transformations of a given medium, I reveal some aspects that are ignored by static models and representations; non-situated, generalist transformations of the processes of public and social communication are revealed.

In the academic community it is common to come across discussions that intend to settle or solve, without success, certain persistent disputes around very stubborn, difficult questions. What is a medium? What are the key elements in a communicational system? Is there something that, potentially, cannot turn into a medium?

In logical, general terms each of these questions, taken seriously, has countless answers. Consequently, they can only be answered resorting to an abstract model or to a restricted answer, a shortcut or rhetorical recourse that dissolves and does not solve the question. It either eludes or postpones it. If today Shannon’s and Weaver’s (1949) communication model still persists, despite the robust criticism that have depreciated it (Martín Barbero & Silva Téllez, 1997) it is because it diluted the challenges of thinking of communication when providing a technical solution that fitted the administration and management of communication by telegraphy and telephony.

But these general questions and the restricted answers reveal their limitations and weaknesses when we observe the concrete evolution of the media, the way they are deployed and lived, the way they articulate with one another, or transform or disappear over time. By questioning its temporary condition, that is, its evolution, some theoretical dualisms, mechanical modeling and simplifying certainties reveal their limitations, and it becomes necessary to build specific instruments and concepts to capture details that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Hence, the usefulness of the studies on media archeology, a transdisciplinary field that was recently created in the 1990’s, from the seminal book by Kittler, Discourse Networks 1800/1900 (Kittler, 1990).5 The term archeology from the etymological point of view alludes to the study of discursive events materialized in archives. Media archeology, according to Parikka and others (Huhtamo & Parikka, 2011; Parikka, 2015; Piccini, 2015), he has endorsed Foucault’s genealogical understanding of institutions and discourses, and the insightful Benjaminan reading of the technique, which unraveled some key transformations of the sensorium, experience and modern urban esthetics when examining the arts of the machine as appreciable in films, photography, journalistic information and architecture.6 Of course, it has gone beyond that. Media archeology has turned out to be especially stimulating when the current media are reread examining the archives, discourses, practices, uses and esthetic and artistic expressions of the media of the past. When underscoring the importance of paying attention to its material aspects, when examining the non-linear evolution of its discursive, institutional and technical transformations, when defying mythologization of novelty -which usually takes for granted that previous media are displaced and replaced by new media just like that −; when developing careful archive excavation and analysis of the technical past to illuminate its connections with the digital culture and contemporary media, media archeology relativizes preconceived communication models and the certainties and limits of what we understand as media. It also compels us to conceive concepts capable of revealing diffused, mixed social practices to detail the conditions that enabled, technically and discursively, the emergence of media and certain social uses to the detriment of others. In other words, this type of studies favors an artisan, detailed work of recognition and excavation of the materialities, discourses, institutional disputes and practices that previously molded the media of today. Screening in medium and long-term social processes, media archeology unearths the roots of contemporary technical culture.

The following are two examples. Tringham and Ashley (2015) pay attention to the life and use cycle of the materials of the dwellings of the past and their simulated recreation in digital environments such as in the Çatalhöyük East Mound Neolithic in Turkey and Okapi Island, there is a simulated version of the former on the digital platform Second Life. Digitalization, regarded as transitory and ephemeral, recreates material constructions that, even though they are lasting, they collapse over time. Intangible digital objects are used to preserve traces of that which, after millennia, becomes eroded despite its material hardness. Bailey (2015) maximizes the archeological metaphor, underscores the impossibility of distinguishing between discursive practice and materiality, and shows how material remains of a technical nature - magnetic tapes, connection cables, computer boards, hard drives - are, strictly speaking, reconfigured, classified, modeled by archeological practice -including their record in digital images and memories that are used as archives−, the same way that archeological findings become such after the classification, inventory and photographing work of material remains of ancient culture.

In general, media archeology emphasizes the connections between esthetic and cultural modernity with the history of the uses, practices and media techniques. It expands the times of digitalization, distancing itself from those discourses that celebrate its novelty and recent condition. It makes emphasis on the non-linear development of the media and the technologies, and on the zealous study of its material condition and the examination of files to understand -using the past- the scopes of, among others, today’s digital culture, DIY, do it yourself, recycling and reutilization of old media (Parikka, 2012), all of this in a socio-technical environment propitious to abundant, continuous, accelerated filing.

Never has a culture been more dynamically “archival” than the present epoch of digital media. By chronotechnical immersion, media archaeology aims at being fast enough to analyze such events as they happen in real time-thus sacrificing the traditional claim by historians and other historicist humanities that only from a temporal distance (a time lag) is critical observation possible. (Ernst, 2015, p. 22).

Artists, and even better, art conservationists have also paid attention to the transitory condition of other types of media: art pieces. According to Besser (2012) this awareness about the materiality and the life cycle of works of art has accentuated with the development of electronic arts, the performing arts, videographies and ephemeral arts.

Many contemporary works of art cannot be re-displayed even a decade later due to fragile materials, technological obsolescence, or other dependencies. Works ranging from sculptures of candy, to those incorporating obsolete video formats or cathode ray tube displays, to works that employ software from operating systems discontinued more than a decade ago -- all these works must be changed in order to be seen at a later date. Conservators call these works "variable media", and groups of museums have undertaken a handful of collaborative projects over the past decade to develop approaches and methodologies for appropriately re-interpreting, re-creating, and re-installing these works in ways that are consistent with the intention of the original work. (Besser, 2012, p. 1).

It is interesting that the awareness of obsolescence and material life cycle of a medium is present in people responsible for conservation such as Besser and not so much so in media analysts and scholars. This awareness is not limited to recognizing the continual obsolescence of technological devices and the machines we use to communicate. It is a fine awareness of the perennial condition of the piece itself and the difficulties to preserve the evanescent. Terminology is English for the endeavor aimed at archiving what disappears and is hard to reproduce are the “Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records” (FRBR) and “Resource Description and Access” (RDA) according to Besser (2012), two types of technical procedures aimed at solving the problem of preserving variable media art. We hardly think about in the fate of those pieces of artistic communication (Everaert-Desmedt, 2006) stored in video game cartridges, floppy discs, slides, video recordings on VHS or Beta, super 8 millimeters, or -thinking about the future- the online files on the Web, the Internet data downloads in real time (Besser, 2012).

One way or another, whether they are media with complex digital assemblies or artisan or mechanical media, their material condition compels us to rid ourselves of the naïve spell produced by presences: they are only revealed to us as temporary when they change or disappear abruptly.

This article examines the dynamics of a medium, a photographic poster, and it provides some conceptual instruments derived from the analysis and observation of material and temporal transformations, including its disappearance as an object. It examines a living, dynamic, and -in appearance- simple medium, to try, starting from its phenomenology and evolution, some concepts that may help us to understand other media.

Following the life and death cycle of a poster: its material disappearance

the decline in circulation of the printed press in the USA and some European countries, and the transformation of the media landscape by virtue of the emergence and consolidation of the Internet or mobile telephony, provide one of the faces of the transitory condition of the media: that of the change in the types of company management and the emergence of other business models (Campos Freire, 2010) to make viable those media that are having problems due to audience dispersion, technological change or the decline of advertising investment in some of the journalistic companies. The media also die out, or disappear or collapse. But notice that in this case what becomes ruined is the organization that produces and distributes the works -books, newspapers, photos, news- which we use to communicate with one another. We usually call “media” the organizational framework that produces the material and symbolic goods that we use to live, to establish links and understand the evolution of the world. We do not call the news or the photo or the newspaper media.7

Street posters are very particular material objects of communication. They are less transitory than an installation or a printed newspaper, but they are more fragile and vulnerable than books and magazines or the posters kept safely in the current movie theaters or inside offices or commercial buildings, street posters seem to proliferate thanks to their relative low cost, their opportunistic effectiveness -they work well in illustrating, denouncing, promoting an ongoing or near-future event, and they are quickly anchored so that people can read them in a fleeting moment-, and their versatility -they admit from very simple configurations to sophisticated, complex communicative and expressive pieces-.

Universidad del Valle, in Cali, Colombia, is a public higher-education institution with a little over 30 000 students and 1 000 faculty. Every day, in its largest campus, located to the south of the city, thousands of people circulate, among them students, staff and faculty. 50 buildings spread in nearly one million square meters, surrounded by wide open areas with trees, small paved streets, pedestrian lanes, squares and public meeting areas. It is common to find institutional notices, lists, directions, graffiti, murals and hundreds of thousands of posters and images that appear and disappear from the building walls over time. In today’s language, marked by the contemporary computer, digital and telecommunicational adventure, walls would be a huge platform on which to circulate all kinds of texts and records: from personal messages to political proclamations, from works of art to the occasional gossip, from open letters to encoded, encrypted messages. We do not know much about this powerful communicational dynamics. Do passers-by ignore, glimpse or read these texts? Do they find them meaningful? How do they use them? How and who design and create these pieces? How many kinds of posters hang from the walls of this university? The fact that we do not have basic information in this regard is indicative of how profound the change in communication studies has been over the years.

If in the 1980’s Jesús Martín-Barbero and Social Communication students at Universidad del Valle conducted small studies, on an anthropological key, about the popular uses of cemeteries and movie theaters in Cali, today it seems that studying the media that people walk along or use bodily, that is, the media that are anchored on the urban geography and landscape has lost relevance, studying the rich diversity of the media marked by the anthropological space (Certeau, 2000) or place (Augé, 2001) has declined. What’s more, the privilege enjoyed for decades by the classical and conventional mass media as object of study seems to be threatened by the penetrating importance of the new media (Manovich, 2005) and the Web. In any case, we are neglecting those that for centuries have populated the noisy plebeian wall, that wall in the cities, universities and squares, in the contexts of both public communication and riots and protests. May this be an occasion to appreciate an old medium and while glimpsing it, observe what we lose sight of when examining the classical and the new media without recognizing their mutual relations and links that, in their genesis and evolution, articulate and build them.8

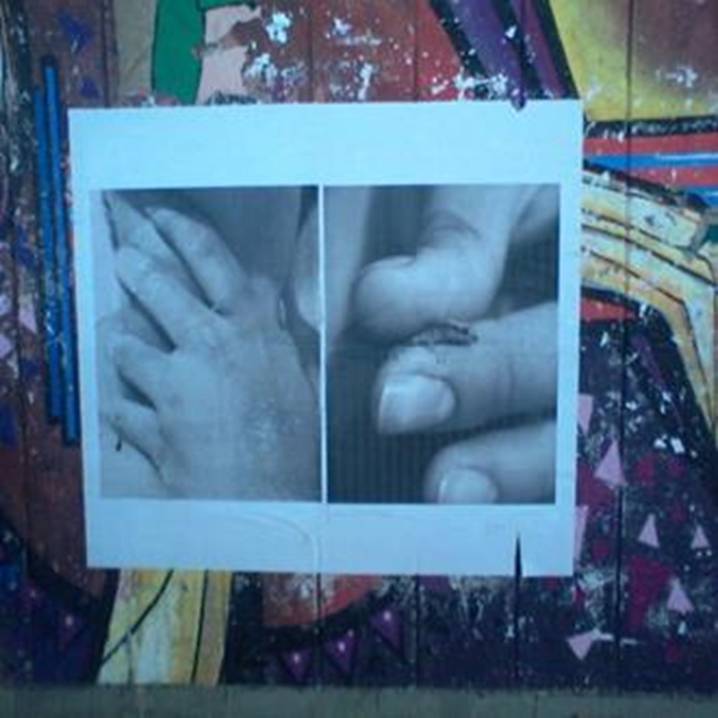

At the Universidad del Valle, I followed the life cycle of a poster for nearly four months until it dissolved and disappeared completely. This photographic poster is unique: it is not an advertising piece, it is not a text of political propaganda or activism, nor does it promote an academic or cultural event, it is not an invitation to some public celebration or party either (the four prevailing topics in posters at the university). It is a genuine work of art displayed in a space exposed to human intervention and the action of the weather. It is a large-format photograph (almost two meters wide by one and a half meters high), it was printed on paper a few millimeters thick, which is very fragile and completely vulnerable (see Figure 1).

It is possible to contrast the life and death cycle of this material communicational object with others that are more protected. For example, institutional posters within buildings preserved within glass cases (see Figure 2); or those in which the paper weight, the type of printing or its display in interior spaces, enable greater duration. What’s more some posters about political criticism and protest have endured the passage of time thanks to the paper’s and the glue’s quality in spite of the fact that they are exposed to the weather.

Figure 2 The frame and glass, in addition to being located in an inner corridor, is the environment where an institutional, protected poster prospers, November, 2014. Instituto de Educación y Pedagogía, Universidad del Valle, Cali.

The piece analyzed in this study remained exposed for between 7 and 10 months before it disintegrated. Some of the posters examined have managed to remain on display for three years. And it is likely for the life cycle of some pieces to last for five-year periods.

The poster: three aspects of a medium

The photographic poster that is the object of our study appeared stuck to one of the walls of the Instituto de Educación y Pedagogía (Education and Pedagogy Institute) wall, on some date between June and August, 2014. It was the only piece on that wall. On lateral walls there were a small mural and some graffiti. But this photographic poster was -to put it in a graphic manner- by itself. I made the first photographic record of the piece on November 7th, 2014 (see Figure 3, left) and the last one on March 9th, 2015 (see Figure 3, right), that is four months later. I made a total of 42 records (a little over two per week).

This small study begins with the image 2014-07-10-19 (Figure 3, right), where it is possible to see a close-up of a person’s face and some drops of water suspended thanks to the adequate photographic illumination and shutter speed. The poster considers another image that is not possible to recognize due to rainwater fading. This double condition -that of a recognizable image and that of a photographic image of which only the remainders of its dilution remain- is interesting, just as it will be highlighted below. For a start, we are interested in paying attention to the medium and not its photographic content.

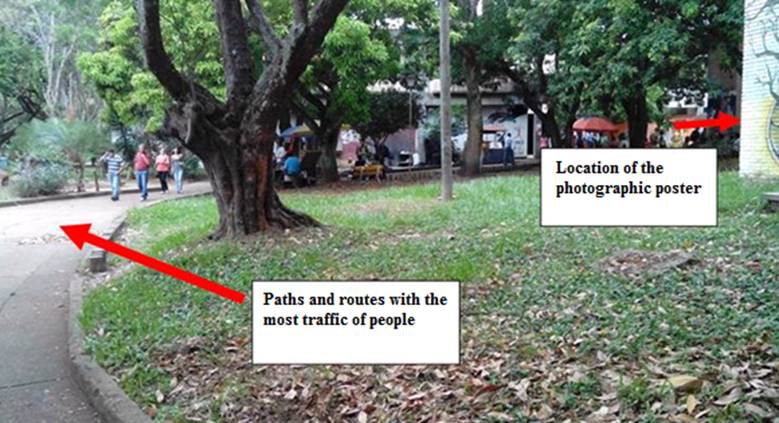

A first approach to the situated, descriptive analysis of the medium begins by examining the place where the photographic poster is located. It arrives in an environment that is rich in preexisting media: the wall, the four-story building, exposure to sunlight, rain water, humidity and the action of living agents (people, animals, bacteria), and a corner that is alive with the circulation and flow of people. It is perhaps one of the most intense environments in terms of people traffic at the university: in addition to being a route of transit towards seven lecture halls and faculties, it is close to a parking lot, the central cafeteria, the coliseum, the sports center and a square.

The people who placed the photographic poster on that wall must have taken into consideration some aspects and they made decisions that I am interested in highlighting next. Questions that have to do more or less with common sense, such as: is there room enough to place the poster there? Will it be visible? Can it be torn down? Can it be seen from a distance? Is the image understood well from 10 meters away? Is it attractive and visible? Will it come off and fall? These are part of a swarm of operations encompassed under the term of previous reading of the media environment. This reading comes together in a set of concrete decisions: the poster is placed there and not anywhere else, it is placed at a certain height, more glue is applied to it so that it sticks better on the wall, care is taken that it be straight and aligned with respect to the edges of the wall, etc. This previous reading of the surroundings of the medium is customary in the production of any communication object: it is made by the designers of an advertising strategy, it is made by a person preparing a letter addressed to a public official, it is set in motion by a writer that will publish his novel or by the pool of producers who decide whether or not to send a film to a given festival. This reading does not operate as a prevision and analysis exercise of the reactions of the public for whom the work is intended; it is absolutely not a calculation exercise about the possible audiences of the communication object, nor about the circulation conditions of the message in the abstract: it is a reading situated in specific time and space, referring to well-defined environments and more or less tangible and, of course to changing, circumstances. It is a situational or contextualized reading and it can be synthesized simply in the following terms: it is the tactical recognition of the preexisting system or media ecology that can be used to balance and adjust the one that is in a development process.

It is not the type of decisions referring to the style of the work, its languages, the esthetic or morphological characteristics of the communication device. This process, as it can be noticed, is different than others that are similar and occur during the process of creating a work. An author or a team of creators or a television network can take into account the public or the audience of the work or medium, the type of institutional or governmental censorship and restrictions, the market conditions, etc, and -starting from these anticipations- define its characteristics. In these cases, the design of the work or the medium is contaminated with external considerations (technical conditions, competition among the media, the market, etc). On the other end, there would be works that resist these external influences more, pieces that are excluded in these types of considerations or those that are completely subordinated to the creation and communication project. But in all these cases, the reading participates in the creation of the work itself. In the case that I am examining, the previous reading of the media does not participate in the genesis of the work, because the piece has already been made. It rather operates as a set of decisions intended to look for the best conditions for publicizing the work and having the medium work.

At that moment, I insert the medium in the preexisting ones, and a story of transformations begins, one that in part, can be observed in the following image of the photographic poster studied, 2014-11-21-3 (see Figure 4). Rain water, light and the wind have taken its toll on the piece. Water has degraded some parts of the photo and washed the image out.

But it is possible to notice that a week after the first record, there are no scratches, graffiti or tears indicating human intervention on the piece. Nothing prevents it and yet, it has not happened. There are no other posters or texts superimposed on the photographic poster or any other graphic or textual piece around it. Relatively isolated, after eleven days the poster remains intact except for the action of the weather agents.

Perhaps when the authors10 designed it, they foresaw these deterioration and change processes as the essential component of the work itself. Other posters contemplate insulation mechanisms and access restrictions to prevent the action of such processes (see Figure 2) or the choice of materials that are less vulnerable to the environment’s action to ensure better visibility and duration.

Then it is possible to observe a second aspect to advance in this ecological and situated understanding of a medium: the presence or not of protecting membranes or limits to preserve it from the action of the agents and media of the environment in which it is immersed. This protection membrane or system can be technical and physical (lasting materials, protection mechanisms such as glass cases or protective screens), socio-spatial (location in a protected place, delimitation of a ritual niche, for example), institutional (legal regulations that protect the medium in the environment in which it is displayed (legal protection, insertion within a fenced off space as it can be seen in figure 2), or a combination of means that preserve and protect the medium promoted (advertising strategies, invitation to take care of the piece, restriction and control of the audiences as it happens with that medium called “master class”, in which competing media such as cell phones, the student’s voice or the presence of distractions are censored or prohibited).11 On this occasion, the medium appears fragilely protected by an invisible membrane that shields the work: the piece enjoys the cultural aura of classical art works. It seems as if it is displayed in a museum, that is, in an exclusive space, in a space for itself. The “aura” (Benjamin, 1989) of this art piece operates as a contention barrier of “endogenous” origin, that is, inherent to the medium, just like a religious piece. No scratch, no graffiti, no tear made by any person at all.

A third aspect refers to traffic: the poster is located on a wall surrounded by open paths and walks (Figure 5). A few meters away it is possible to see sidewalks and foot paths that are heavily transited. The flow of people along these routes increases at the start of the school day (8:00 am), at noon -when people visit the university cafeterias-, and at the end of the school day (6:00 pm). That is, there are moments at which the poster is more and less exposed to the action of people. It is worth noticing, though, that “traffic”, “exposure” and “display” are terms that designate something else: the fact that there are preexisting media that capture, modulate and guide flows of people that, the studied medium (the photographic poster), can eventually integrate and capture. The traffic of preexisting media does not always compete with the medium that has just been installed: contrariwise, it can take advantage of it, join it. In an economy of attention, (Goldhaber, 1997, 2006) it is perfectly possible for a medium to accumulate audience and traffic for another and vice versa.12 In fact, as opposed to the more or less rooted idea according to which the media in general “compete with one another”, it seems more reasonable to notice that the usual is some kind of more or less regular and frequent convergence among the media. The poster is not competing with the traffic of pedestrians. The image does not compete with the array of objects displayed in the space in which it is installed. Establishing whether in a media environment there are relations of competition and relations of convergence, whether the media come together in differentiations of traffics and publics, whether they overlap, can help us break some analytical inertias and problematic pre-concepts such as that of “media convergence”, associated with the digital nature or the corporate integration of the media businesses.13 The idea according to which some media cannibalize others only makes sense where commercial, profit relations that are clearly antagonistic rule. It is less clear on the wall of the panorama.

Passage of time: the dynamic condition of all media

It is interesting, though, to observe the process of deterioration and transformation of the medium as a set, in its entirety, hardly two months after the first record. On the January 6 record (Figure 6), the photographic image on the poster has all but disappeared and the support paper is beginning to tear. A new detail can be made out on the support paper, as if it were a palimpsest: a network, white and black graffiti. “E.L.N”14 can be read. This element provides for us a new aspect: media converge (if the traffics are taken into account), but they also overlap (one another). Overlapping is revealed just when a medium collapses or dissolves, or when a new medium is mounted on a previous one. Then, the relations among media would consider, in addition to convergence and competition, concealment and superposition. This time, the E.L.N graph was mounted only when the poster had deteriorated almost completely, that is, when it had already lost some of its aura as a work of art.

In addition, it can be observed that deterioration -in this case- is advancing in layers. First pigmentation disappears, dissolved and deformed by water, light, heat and wind, and some microorganisms. Shortly after the deformation of cellulose and paper (the support) follow, it swells, comes off, breaks or curls up until it finally falls into pieces. But the interesting fact is not just the deterioration of the medium, but rather that along the entire process, at no moment does the medium stop conveying meanings. In fact, although the frame on the right of the first record (Figure 3) dissolved early, it was not intervened in months. Only when it collapsed completely was the other one superimposed. That is, at no moment is there void of meaning. There never is “nothing”. This persistence of sense and meaning reveals a new aspect to be considered in this small analysis: people convey and set meanings and senses continually and consequently there never is utter emptiness, even if the medium has almost disappeared completely. Of course, on the basis there is some iconic drive (the tendency to order and seek meaning, see shapes and icons in any image) and scopic drive (the pleasure of seeing, the desire to see)15 at stake.

Just a few months have elapsed from the earliest washed out images (Figure 3) to those in which almost all traces of pigmentation have disappeared (see details in Figure 8). And a new aspect should be added to the persistence of meaning: the trace. That is, we are not just witnessing the human capacity to produce sense and meaning continually from any indication. Also, the medium contains the rests of what it used to be and the future readings are structured around those traces. We would have to speak of “media trace”, that is, the material persistence of a medium in such a way that it serves for the genesis of future readings and future media that succeed it genetically? The adventure of the small poster (photography) that had been printed on delicate paper, a photography made to be degraded rapidly, found a new version at the Universidad del Valle, a few months later (Figure 7). The esthetic project after this set of works does not matter in this analysis: what ist has as a medium is what matters. Then it can be affirmed that the fragile photo, or the photo printed on fragile material, which has been worked on at length in art history (see, for example, the recent works by artist Oscar Muñoz16 using water as support and medium),17 becomes a medium and traces for future media.18

Figure 7 A new ephemeral photographic poster, displayed on one of the central cafeteria’s wall at the Universidad del Valle. Recorded on January 16th, 2015

By February, 2015 only some traces of the ELN record remains and the photo has disappeared entirely (Figure 8). That is, the traces of the first medium has dissolved (photographic poster) and the rests of the second poster remain (the ELN poster). The cycle of the medium has been completed. It is interesting that, once all traces of the posters disappear from this wall, this space has been marked and it has transformed into a “place where new posters can be displayed”. That is, it has been charged and enriched as a medium on which other media can be displayed.

On Friday June 12, 2015, I took the last photography of the medium described in the follow-up. There were some traces of the poster and there is a new graffiti: “No hay paz sin justicia social” (There is no peace without social justice). To conclude this follow-up, I would like to discuss several issues revealed in this small final scene (Figure 9).

A simple, changing medium: some lessons

In sum, it is important to notice that a medium, even when it disappears, creates a “space of possibilities”. This place on the wall could have been potentially consecrated and regulated progressively until it became a corner reserved for photographic posters or, as it indeed happened, coexist with other adjacent, overlapping media. Over time, that space possibilities becomes diluted and eroded if there is no activity that renews it. The fact that the persistence of a medium depends closely on apparently trivial, but actually very relevant human work that sets it in motion once and again, presupposes an aspect that can go unnoticed: a medium is not just an environment that communicates, but also an environment that is provided as an opportunity for replication and reproduction. People do not just watch television, read the paper or look at a photo. They do not just consume a medium. Its use paves the way for its potential reproduction. When watching television or reading books or looking at a photographic poster on a wall, when observing a graffiti or seeing a road traced on the urban space that we go through, we are appropriating and learning criteria, formats and models about how a road should be traced, how a book should be written or how a graffiti or poster should be designed. Use transforms the consumer into a potential producer, understanding that the condition of producer entails a wide range that goes from the person who can recognize and criticize the suitability or not of a medium to patterns and limits they have known, to the person who becomes a television creator, a creator of adequate roads, books or photographic posters on a public wall. Every medium entails reproduction guidelines and formats. Using, consuming and reading the medium reinforce a sort of appropriation of the way in which the medium should and can be. A medium user does not only “understands the content” but also the “form”, the formats, in such a way that, when that user for some reason becomes a producer or maker, at the creation decision-making moment they will shuffle, among other options, those that have to do with the “forms of medium” that they know and have used. Perhaps that partly explains the genetics of media, that is, the way in which a medium is deployed using keys of preceding media. The work of people who have appropriated and assimilated forms of previous media operate between one given medium and a similar one.

Media are dynamic, that is, they are affected and transformed over time, and tracking that temporal dimension is relevant. Setting in motion a medium presupposes a complex previous reading of media from which decisions are made regarding the installation and execution of the new medium. Understanding that every medium presupposes a “previous reading of media” by those people in charge of their execution and production is relevant. This reading molds and defines many of the operation decisions of the specific medium. There are media that entail endogenous and exogenous membranes and frontiers of protection and reproduction: endogenous ones have to do with the internal nature of the medium itself, and exogenous ones imply physical frontiers (frames, glass cases, walls) or institutional (museum regulations, access limits) that protect the course of the medium. There are relations of competition and relations of convergence among the media around traffics and the public. There is rich overlapping as well.

The idea according to which the media compete for the public is limited. And so is that which suggests that today’s convergence of media would be explained by a) a sort of technological synergy or b) by virtue of a new structure of integration of media businesses and companies (multimedia companies). Also, a medium’s dynamics presupposes the continual production of meanings by the people who use it. There is never complete void of meaning and sense. That is why any indication, even the traces and rests of the medium’s materials as they dissolve, continue providing possible readings. This work on meaning and sense set by the people who use the medium is a central component of the medium itself. Finally, the medium considers forms, formats and configurations that the people appropriate when they use it. These forms will opt for new media when some of these people become, in turn, creators or producers of media intended for similar functions and purposes. A medium, then, needs a set of conditions essential to its persistence and permanence before it dissolves and disappears.

Spurred on by what has been referred to as material turn (the emphasis on the material aspects of the media), Wythoff (2015) writes and recognizes Foucault’s importance in the advent of this turn. His words are in perfect tune with the scope and dimension of this small study, and I quote them in the end, because they suggest to what extent we ignore the deep penetration of absences, of transformations and disappearances when we fall under the spell on the presences:

first, that discernible objects and perceptual codes are themselves the products of media technologies. All modes and kinds of knowledge bear the imprint of those instruments used to record, organize, and express them. And second, that the histories of these technologies must take into account the curiosities and forgotten paths not taken: quirky or fantastic inventions that either never made it to the mainstream or now evoke a kind of retro-tech nostalgia (stereoscopes, hand-cranked 8-mm film viewers, card indexes, magnetophones, and the like). Part of the field is the simple challenge, common to all good theory, to think the present state of things differently. What if the tablet computer took off as it was originally proposed in the 1970s as a teaching platform for object oriented programming, rather than the app vending machine it is today …? What if the metaphors we use to understand hidden computational operations-like copying a file, visiting a site-were fundamentally different …? (Wythoff, 2015, p. 24)

REFERENCES

Akrich, M., Callon, M. & Latour, B. (2006). Sociologie de la traduction: textes fondateurs. París: Mines Paris, les Presses. [ Links ]

Augé, M. (2001). Los "no lugares": espacios del anonimato. Una antropología de la modernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Bailey, G. (2015). Symmetrical media archaeology: Boundary and context. Journal of Media Archaeologies, 2 (1), 41-52. [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. (1989). La obra de arte en la era de su reproductibilidad técnica. Discursos Interrumpidos I. Buenos Aires: Taurus. [ Links ]

Besser, H. (2012). Contemporary art that does not last without being changed: Issues for librarians. Art now! Contemporary Art Resources in a Library Context 2012 IFLA Satellite Conference. [ Links ]

Brown, S., Callon, M., Latour, B., Law, J., Lee, N., Michael, M. et al. (1998). Sociología simétrica: ensayos sobre ciencia, tecnología y sociedad. Barcelona: Gedisa . [ Links ]

Campos Freire, F. (2010). Los nuevos modelos de gestión de las empresas mediáticas. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico (16), 13-30. [ Links ]

Carrasco, I. & Vivanco, M. (2011). ¿Sistemas dinámicos en ciencias sociales? Revista de Sociología (26), 169-191. [ Links ]

Certeau, M. D. (2000). La invención de lo cotidiano. I: Artes de Hacer. México: Universidad Iberoamericana/ Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente. [ Links ]

Ernst, W. (2015). Media archaeology-as-such: Occasional thoughts on Més-alliances with Archaeologies Proper. Journal of Media Archaeologies, 2 (1), 15-23. [ Links ]

Everaert-Desmedt, N. (2006). La comunicación artística: una interpretación peirceana. Signos en Rotación, 3 (181). Recuperado el 16 de octubre de 2010 de Recuperado el 16 de octubre de 2010 de http://www.unav.es/gep/Articulos/SRotacion2.html [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1992). Microfísica del poder. Madrid: La Piqueta. [ Links ]

Goldhaber, M. H. (1997, 7 de abril). The attention economy and the net. First Monday. Journal on the Internet, 2 (4-7). Recuperado de http://firstmonday.org/article/view/519/440 [ Links ]

Goldhaber, M. H. (2006). The value of openess in an attention economy. First Monday. Journal on the Internet, 11 (6-5). Recuperado de http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1334/1254 [ Links ]

Gubern, R. (1992). La mirada opulenta. Exploración de la iconosfera contemporánea. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [ Links ]

Gubern, R. (1996). Del bisonte a la realidad virtual: la escena y el laberinto. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama. [ Links ]

Hartley, J. (2004). Communication, cultural and media studies: The key concepts. Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Huhtamo, E. & Parikka, J. (Eds.). (2011). Media archaeology: Approaches, applications and implications. Los Ángeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. Nueva York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Jensen, K. B. (2014). Introducción. La convergencia en las investigaciones sobre medios y comunicación. En K. B. Jensen (Ed.), La comunicación y los medios: metodologías de investigación cualitativa y cuantitativa (pp. 13-40). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Kelso, S. (1999). Dynamic patterns. The self-organization of brain and behavior. Massachussets: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Kittler, F. A. (1990). Discourse networks 1800/1900. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2007). Nunca fuimos modernos. Ensayos de antropología simétrica. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores. (Trabajo original publicado en 1991). [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2008). Reensamblar lo social. Una introducción a la teoría del actor-red. Buenos Aires: Manantial. [ Links ]

Manovich, L. (2005). El lenguaje de los nuevos medios de comunicación. La imagen en la era digital (Traducción por O. Fontrodona). Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós. (Trabajo original publicado en 2001). [ Links ]

Martín Barbero, J. (1987). De los medios a las mediaciones. Comunicación, cultura y hegemonía. México: Gustavo Gili. [ Links ]

Martín Barbero, J., & Silva Téllez, A. (1997). Proyectar la comunicación. Bogotá: Instituto de Estudios Sobre Culturas y Comunicación. [ Links ]

Martín Serrano, M. (2007). Teoría de la comunicación: la comunicación, la vida y la sociedad. Madrid: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Monea, A., & Packer, J. (2016). Media genealogy and the politics of archaeology. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3141-3159. [ Links ]

Parikka, J. (2012). Introduction: Cartographies of the old and the new. What is media Archeology? (pp. 1-18). Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Parikka, J. (2015). Sites of media archaeology: Producing the contemporary as a shared topic. Journal of Media Archaeologies, 2 (1), 8-14. [ Links ]

Piccini, A. (2015). Media-archaeologies: An invitation. Journal of Media Archaeologies, 2 (1), 1-8. [ Links ]

Puche Navarro, R. (Ed.). (2009). ¿Es la mente no lineal? Cali: Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle. [ Links ]

Roca, J., & Wills, M. (2011). Oscar Muñoz, Protografías. Recuperado de http://www.banrepcultural.org/oscar-munoz/curaduria.html [ Links ]

Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal, XXVII (3), 379-656. [ Links ]

Shannon, C. E. & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Tringham, R., & Ashley, M. (2015). Becoming archaeological. Journal of Media Archaeologies, 2 (1), 29-41. [ Links ]

Wythoff, G. (2015). Artifactual interpretation. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 2 (1), 23-29 [ Links ]

2See Kelso (1999), Puche and others (2009) and Carrasco and Vivanco (2011) about the approaches to dynamic systems.

3Of course the notion of agent alludes to distinctions established by Latour and others (Akrich, Callon & Latour, 2006; Callon et al., 1998; Latour, 1991/2007; Latour, 2008).

4This article derives from the research project Observatorio de Fenómenos Emergentes de Información, of the Grupo de Investigación en Periodismo e Información, Escuela de Comunicación Social, Universidad del Valle. The project has been entirely financed by Universidad del Valle, a public institution. For more references see http://ciudadvaga.univalle.edu.co/index.php/observatorio.

5 Monea and Packer (2016) hold that, in addition to Kittler, Wolfgang Ernst and Siegfried Zielinski would be the precursors of media archeology.

6 Monea and Packer (2016) have criticized excessive emphasis on archeological aspects –situated, fragmented, synchronic and media-centered works– overlooking what Foucault (1992 ) would recognized as one of the limitations of his earliest works: losing sight of continuity and permanence of power, omitting duration and continuity, in other words genealogy. That is why even Parikka and the recent literature on media archeology underscore the importance of thinking of media archeology and genealogy.

7It seems necessary to both of them to be called “media”, both the producing agent and the product. Hartley (2004) provides for us a restricted definition of media– “A medium (or media, in plural) is simply any material through which it is possible to transmit something else” (Hartley, 2004, p. 142), As an extended, broad definition –the media are the mass media, the centralized industries that produce contents from one to many, and, since the 1990’s, by virtue of the integration and convergence of computer and telecommunicational interactivity processes, the media enable many-tomany communication. However, some studies provide understanding and theses that broaden and explain what the media are moderating the emphasison devices and techniques, on the organizations and companies, in the contents and products themselves, or in the forms of contemporary sociotechnical integration, and they delve in long-lasting processes in cultures –for example Martín-Barbero (1987)-, the evolution of the species– such as Martín Serrano (2007), or the different planes of social life –Jensen (2014). For this entirely phenomenological and situational study, the medium is both the poster exhibited and exposed to dynamics in a changing social environment and the set of institutional and material conditions that enable the presence of that poster.

8The Observatory of Emerging Information Phenomena has set as a condition studying public communication anchored to a physical, geographical space in a relational manner, with industrial communication media and the new emerging media.

9Taking advantage of the metadata system of cell phones and modern photographic devices, the name of the images considers the date (year, month and day) and I have added a number indicating the sequence of photos obtained on the same day. This way a photo 20140601-1, is indicating that it was taken in the year 2014, in the month of June (06) and on the first day (01), and it was the first (1) recorded in respect of this object on that day.

10We have no information about the authorship of the piece and the creative project that this poster entailed.

11We have learned to recognize these regulations and membranes now that, surreptitiously or blatantly, students manipulate their cell phones or tablets while their teachers try to control their attention.

12 Alexa.com, the Amazon website specialized in Internet indicators and metrics, usually monitors the users’ navigation trajectories, examines where the users go after visiting a Website. In the West, the triangle of Web attention has so far been called using the acronym gift you: Google, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube.

13Fortunately, Jenkins’ work (2006) helped moderate that purely technocorporate understanding of media convergence.

14Initials that stand for Ejército de Liberación Nacional, National Liberation Army, a Colombian guerrilla organization.

15In this regard, see Gubern (1992, 1996).

16His work can be seen at http://www.banrepcultural.org/correos/exposiciones/2011/1123_oscar_munoz_protografias-02.html

17These are portographs or first photographs, ephemeral, unstable photos, before they are attached on a surface for some time. According to Roca and Wills (2011), Muñoz recovers from Nicéphore Niépce precisely that first gesture, the protofotographic one, the one that precedes the final capture of the luminous print on the plate.

18It would be possible to imagine a fragile or ephemeral mural press, on which unique, unrepeatable stories and pieces of noteworthy journalistic quality are displayed on the city walls only to later disappear for good without a trace. This idea of a medium of noteworthy quality made not to persist, but to dissolve, to act in a unique, unrepeatable edition can become a bizarre type of medium.

Received: June 02, 2016; Accepted: January 05, 2017

texto en

texto en