Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.29 Guadalajara may./ago. 2017

Articles

Change on representations within Chilean retail advertisement characters in the context of sociocultural changes and new consumption logic (1997-2013) 1

2Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile.

This work reviews Chilean retail advertisement based on a content analysis of ads in printed media during 1997 and 2013, in order to link the observed changes with the sociocultural evolution of the country. The results show a more active participation from the consumers towards the supply, with advertisement trying to integrate them -as characters- and making them an active part of the message.

Key words: Advertisement; Chile; cultural change; content analysis; retail

Se realizó un análisis de contenido cuantitativo de avisos del retail chileno publicados en 1997 y 2013, buscando asociar los cambios observados con la evolución sociocultural que ha experimentado el país. Los resultados dan cuenta de una participación más activa de los consumidores ante la oferta, donde la publicidad busca integrarlos -como personajes- y hacerlos parte activa del mensaje.

Palabras claves: Publicidad; Chile; cambio cultural; análisis de contenido; retail

Introduction

Advertising is regarded as playing a pivotal role in modern culture to the extent that it constitutes a key element in shaping consumer society and consumer lifestyles. As both a reflection of culture and a factor that helps to shape it, advertising promotes an ideology of consumption. This provides individuals and communities with a set of values and behavioral norms that stimulate a society’s development.

Seen from this dual aspect of both “cultural product” and “cultural producer”, while recognizing the lack of academic research and systematic inquiry into advertising, particularly in terms of its cultural associations, this article aims to explore and identify patterns of change and continuity. This will shed light on the ways in which individuals have been represented in printed retail ads in Chile. Our analysis therefore focuses on two separate periods during the last 20 years: 1997 and 2013.

To support our research, we conducted a quantitative content analysis using predetermined categories to classify characters in terms of their socio-demographic profile, as well as formal or informal aspects relating to their appearance, the activities they are engaged in, and the ad setting. Our research is thus intended to determine, in an exploratory fashion, the relationship between the changes identified in the characters featured in the ads and the sociocultural developments occurring in Chile over the same period.

We selected retail as the focus of our study given its economic importance (representing nearly 20% of Chile's GDP, Gross Domestic Product), the high investment in advertising (almost 16% in 2011), and the broad socioeconomic scope of its products and target audiences (retail is understood here to comprise department stores, drugstores, DIY stores and supermarkets).

Advertising as a core component of contemporary culture

As a field of research, advertising poses many challenges given the inherent complexities that derive from its essentially economic purpose, and the fact that it has, in consequence, assumed increasing social, cultural and institutional importance (Eguizábal, 2007; Caro, 2007).

Since its conception towards the end of the 19th century as a mediating instrument in the relations between producers and consumers, advertising has evolved to assume a range of new roles. On the one hand, these are rooted in the transformational processes that have occurred in the systems of production, distribution and the marketing of goods and services, as well as improved communication technologies; but they are also a product of the sociocultural development stimulated by these changes, in which advertising itself has played a significant part (Henry, 1963; Douglas & Isherwood, 1978; Jhally, 1987; Lipovetsky, 2007).

As well as becoming a social institution, with its resultant influence on socialization processes and system cohesion (Williams, 1999; Ibáñez, 1989), advertising has become an agent of demand creation and stimulation, a tool for brand building and positioning, and an inherent component of new organizational and institutional imagery. Now that the logic of advertising has permeated practically every aspect of our social lives, it has become the dominant language and a leading actor in the public arena (Mattelart, 1989; Zunzunegui, 1985, quoted in Caro, 2007).

In view of these factors, advertising is recognized today as a keystone of modern culture, and a core element in the shaping of consumer lifestyles and consumer society. It has performed this same role in the transformational journey that manufacturers have embarked upon, in order to cast themselves, through their brands and products, as immaterial and intangible (semiotic) entities, purveyors and generators of worldviews, identities, values, expectations and cultural meanings (McCracken, 1986; Bauman, 2002; Hellin, 2007).

Accordingly, while advertising helps to sustain market competition, it does so through the deployment of brand imagery, i.e., worlds of meaning that transcend, expand, redefine, differentiate and add value to social objects, irrespective of their material properties, and without being anchored solely in the product (Caro, 2007; Semprini, 1995; Fraenkel & Legris-Desportes, 1999); these social objects are thus recast as a "cultural model" (Williams, 1999, p. 422).

Luther, McMahan & Shoop (2008) stated some time ago that advertising has been recognized by the specialized literature as not only “mirroring” culture, but also having the capacity to influence it. According to Schudson (1986), this affects behaviors and values by creating a consumption-based ideology and by providing individuals and communities with behavioral norms (see Kang, 1997; Frith, Shaw & Cheng, 2005; and Pollay, 1986, quoted by Luther et al., 2008).

It is at the cultural level that advertising exerts its influence (Canevacci, 2001) by means of the representations it engenders. These representations encapsulate and anticipate new social meanings, which are then "consumed" by audiences, regardless of any act of purchase (Caro, 2007). This process is one of cultural learning, acquired through advertising and consumption (Trindade & Ribeiro, 2009, p. 207).

Consistent with the research of Williams (1999) and Baudrillard (1988) among others, our own understanding of advertising is that it represents one of the most important means of contemporary social communication, as well as the most authentic product and clearest expression of consumer society (Rodríguez & Mora, 2002, p. 21).

With that in mind, we recognize the value of advertising research, which has thus been suggested as an instrument by which to gain a better understanding of society, given that advertising not only reflects the cultural mood of the time, but also helps to shape it. In accordance with González Martín (1982), we note that advertising is the conduit through which society is outwardly expressed, whilst at once “consuming” its own image.

Advertising and cultural change in Chile

From 1975, and following the coup d'état of 1973, Chile witnessed an explosive growth in advertising as a consequence of the establishment of the free-market economic model (Vergara, 2003). Its expansion was to have major economic and sociocultural implications, by influencing the way in which Chilean society's expectations and desires began to be represented and promoted (Catalán & Mella, 1982). Up to that point, the communicational role of advertising had been constructed around a strong State, acting as both director and coordinator of change; this, however, gave way to another that was centered on the consumer and his or her interests, thus laying the foundations of a new culture (Larraín, 2001).

Two factors would reinforce the centrality of consumption in the 1990's: firstly the return of democracy (1990), which signified the recovery of public freedoms and certain adjustments to the economic model, thus facilitating its expansion, consolidation; and secondly, rapid economic growth, which doubled the population's per-capita income. Against this backdrop, 1997 (the first year of analysis) marked an end to what was regarded as the "golden decade" of the Chilean economy, characterized by sustained GDP growth (with an annual average of 8%), and ushering in a new era of political, economic and sociocultural openness to the world (though it would also culminate in the "Asian crisis” of 1999. Rodríguez, 2002), It was also the phase during which Chile came to be regarded as a "model country in the region" (Siavelis, 2009; Drake & Jaksic, 1999; Subercaseaux, 1996).

These events ensured that consumption would occupy a prominent role in people's daily lives, as a focal point of social relations (Tironi, 1999), to the extent that it became the physical crystallization of individual identity and a new material anchor for social ties (Siavelis, 2009; Drake & Jaksic, 1999; Subercaseaux, 1996). The importance of consumption was reflected by a rapid increase in the number of credit cards issued, which increased fourfold over the period, soaring from one million 350 thousand in 1993 to more than seven million in 2000, as well as the growing impact of shopping malls, which received twice the number of visitors over a four-year period: 91 million in 1996 to almost 180 million in 2000 (United Nations Development Programme, UNDP, 2002).

Meanwhile, advertising expenditure also doubled between 1990 and 1997, reaching a total of 1.1 billion dollars, a record figure that was not exceeded until 10 years later (Asociación Chilena de Publicidad - Chilean Advertising Agents Association, ACHAP, 2012). Advertising thus began to assume a leading role in the media, a step towards becoming a key referent in the social construction of reality and in the establishment of social identities (Fontaine, 2001; Moulian, 1997).

Once the Asian crisis had subsided, the country again returned to growth rates of more than 4%, except during the sub-prime crisis that occurred between 2008 and 2009, and whose effects lasted until 2013. On the other hand, following a period of instability between 1999 and 2003, advertising expenditure returned to growth rates higher than 4% up to 2007, before falling sharply in 2008 and 2009. Nevertheless, between 2010 and 2011, growth in expenditure recovered to levels of more than 10%, before reaching an all-time high of 1.4 billion dollars in 2013, the second year chosen for our analysis (ACHAP, 2013). A further important factor to be considered in the context of our research was the rapid expansion in the number of credit cards issued by the major department stores over the last 10 years. By the beginning of 2009, the figure had reached almost 20 million, far exceeding the total population of Chile, although it dropped again in 2013 to around 14.7 million (Retail Financiero, 2013).

The retail sector in Chile

Retail is understood to refer to the collection of companies specializing in the commercialization of mass-market products, oriented towards the end consumer. The sector mainly comprises large stores whose primary activity involves the distribution and sale of retail goods. It can be divided into four categories: supermarkets, department stores, drugstores and DIY stores.

The retail sector has particular relevance in Chile if we keep in mind its 20% GDP contribution, with an annual growth rate of 11% between 2003 and 2007; the country was also witness to the extensive consolidation of ownership during the same period. As regards the country’s major department stores (the primary focus of this article), Falabella, Ripley and Paris together account for 80% of market share. In 2011, advertising expenditure for the retail sector represented 16% of the total investment in traditional media, with Falabella accounting for the largest share among the three department stores.

Methodology

For the purposes of this study, we analyzed ads from the years 1997 and 2013 published in Chile's most prominent nationally circulated newspapers that, together, concentrate the highest level of advertising expenditure in the country: El Mercurio, La Tercera and Las Últimas Noticias. We recorded samples from six months of every year (starting in January and continuing on a month-by-month basis until November). We reviewed seven editions of each newspaper every month. These were selected using the systematic "skip" method to establish a different constructed week for every paper, in order to ensure a greater spread of the selected ads. Repeated items were discarded.

The sample from 1997 was recorded and coded by undergraduates from the Faculty of Communications during two research seminars. For this reason, their findings can be regarded as somewhat exploratory in nature. The 2013 sample was recorded and coded by a team of six assistants specially trained for this purpose.

The study was supported by a content analysis conducted from an ad-hoc data sheet based on research by Rodríguez, Saiz & Velasco (undated), whose classification categories were used to guide the description of general ads as well as those referring to representations of individuals in terms of their formal appearance.

Main findings

In the data collected from 2013, 732 ads were selected and classified, 266 of which did not feature characters (36.6%). Of the 580 ads recorded and analyzed in the data collected from 1997, 416 did not feature any characters (71.7%). This is the first aspect that should be highlighted, i.e., the significant variation in the proportion of ads that featured images of people, because it shows the evolution of advertising in Chile, as well as the rapid rise of the consumer society, whose codes are better managed by today's population. Although the higher number of images featured in 2013 may be attributable to economic and technological factors, on account of lower reproduction costs, previous analyses of the 1997 sample indicate a similar upward trend (see Gómez-Lorenzini, Vergara, Porath & Labarca, 2016).

The ads from 1997 clearly exhibit a tendency towards the use of denotative messages, expressed in texts informing consumers of a varied and plentiful supply of low-priced products, as opposed to a more sophisticated communicative message that addresses variables such as lifestyle. In view of this change, we contend, as a guiding hypothesis for the analyses below, that the notable presence of characters in 2013 indicates a shift towards achieving a more deliberate and active identification of a different kind of consumer.

A second interesting variation to highlight concerning the use of imagery in the ads from both research periods is the proportion of characters identified and classified as "individuals" and "groups" (i.e., groups of individuals with similar socio-demographic and phenotypic characteristics performing the same activity). In 1997, 78% of characters were classified as “individuals”, with the remainder entered in the “group” category (22%). In 2013, on the other hand, the number of groups dropped to 6%, whereas the number of individuals rose to 94%, indicating a trend towards greater individualization in character representation.

More women, more youths, and closer proximity to the consumer

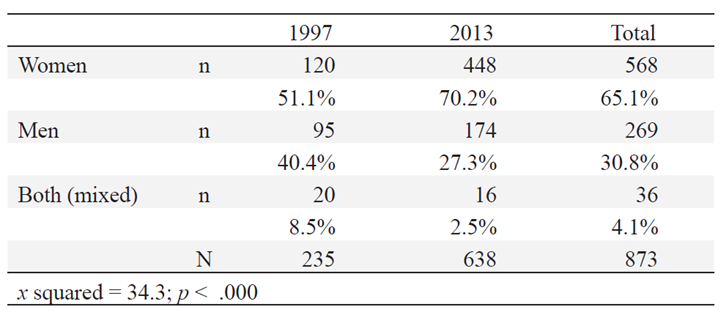

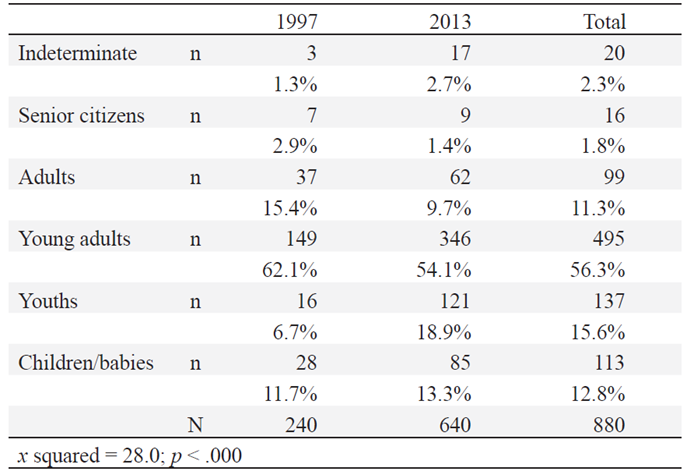

Comparing the first and second samples, we observed, on the one hand, a notable increase in the proportion of women portraying characters in retail ads (Table 1); on the other hand, there was also a trend towards greater representation of youths (Table 2). The proportion of adults and young adults dropped significantly in 2013 compared to 1997, and there was an increase in the characters classified as “youths”. Nevertheless, “young adults” continued to rank highest in terms of representation.

We also noted a substantial reduction in the number of full-body images (64.4% in 1997 versus 25.3% in 2013) and an increase in the use of close-ups and "American shots", a type of framing used in almost half the images published (Table 3). These findings are consistent with our proposed notion of an advertising style that seeks new ways of attracting consumers.

To sum up, we first see more individuals portrayed in retail ads; most tend to be women, who are younger and cast to reflect more closely the target audiences of 1997.

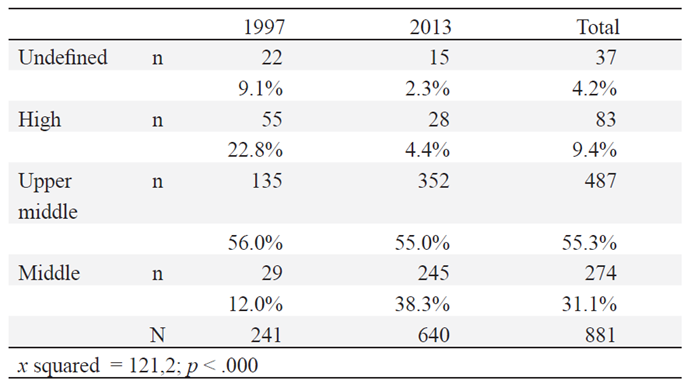

Increase in number of middle-class characters and continuing use of the caucasian phenotype

In keeping with the predetermined categories, between 1997 and 2013, the number of characters classified as “high-class” dropped significantly (less than 5%), whilst the number of "middle class" characters increased. Despite this, the number of “upper-middle” characters remained prevalent, at levels of around 56% (Table 4).

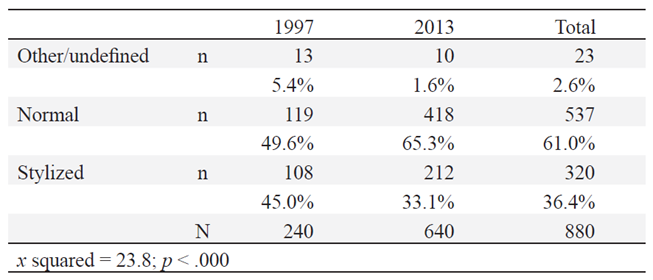

As Table 5 indicates, the physical shape and build of characters now tends to be primarily "normal" (65%), rather than those categorized as having "stylized bodies" (model or sporty types). Here we can see perhaps a further example of the way in which advertising attempts to bring characters closer to the population at large. There is also perhaps a strategic aim here, considering the increasing purchasing power of the middle and lower classes.

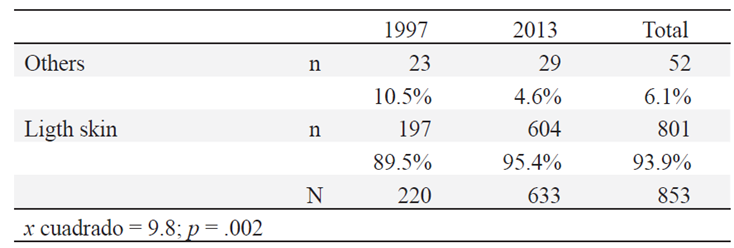

Despite the variations described above, there is one aspect that remained constant throughout the 16-year period: the Caucasian prototype of characters featured in the advertising images. Tables 6 and 7 reaffirm that hair color has maintained similar levels to those in 1997: dark hair continues to be under represented, despite being the most common hair type among Chileans overall. Similarly, there is an overwhelming predominance of white-skinned models; indeed there is even a slight increase.

Characters in less formal clothing

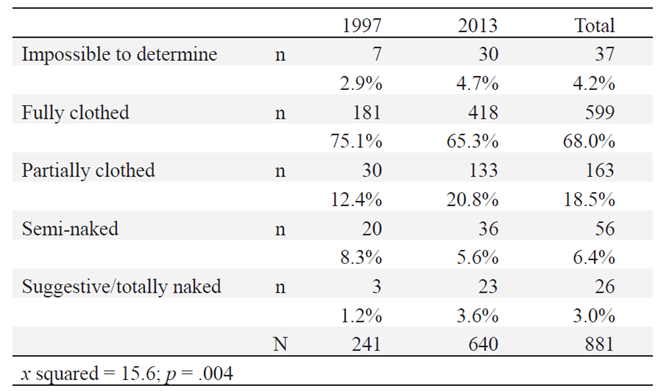

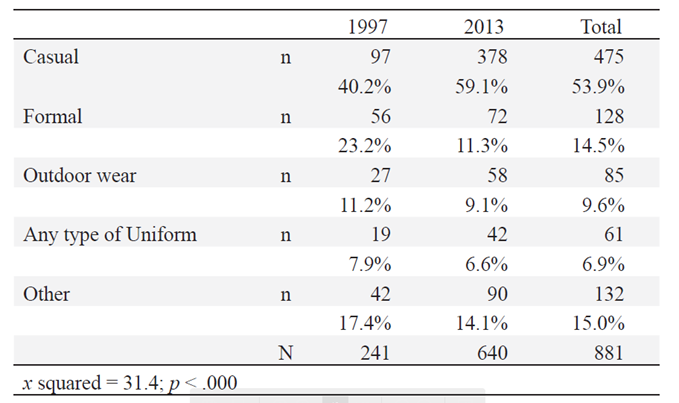

Although fully clothed characters remain predominant (falling from 75.1% to 65.3%, Table 8), there is an increase in the number of characters wearing "partial clothing", generally consisting of lightweight clothing, with shoulders and legs visible (rising to 20.8%). We did not observe any significant increase in the "suggestive clothing" or "full nudity" category. Consistent with this classification and with regard to the type of clothing worn, Table 9 shows an increase in the number of casually dressed characters, rising to 59.1%, but the number of formally dressed characters fell from 23.2% to 11.3%.

These results are consistent with those observed in other areas, such as the field of social communications, for example, where an increasing informality is clearly evident, extending across social networks and including representations in the more traditional media. Today, language and style is significantly more relaxed, very different from the formal and strict styles that were still visible by the end of the 90s.

Social role of characters, activity and setting

When analyzing the function or social roles performed by characters in the ad’s contextual recreations (Table 10), it is worth noting that the proportion of characters occupying a family role within the group (around 16%) remains constant during the period under analysis. This includes all characters portraying the role of father, mother, son and daughter, etc. This is interesting, given the general acceptance (supported by substantial statistical evidence) that the make-up and types of families in Chile have become markedly diversified over the last 20 years. This can be explained by several factors, not least by the Chilean law that permits divorce, and that was enacted as recently as 2004. It is perhaps the case, therefore, that the internal make-up of families represented within this percentage has changed (for example, from the nuclear to the single-parent family) but the impact on retail ads has remained constant.

In terms of the images, there has been a considerable drop in the number of anonymous consumer representations (dropping from 54.4% to 16.6%); this has occurred simultaneously with an increase in the presence of celebrities ("faces") and experts (rising from 6.7% to 29.4%). One possible explanation for this trend is the growing mediatization of Chilean society, and, as a consequence, the increasingly prominent role of well-known personalities in the media. The weakened credibility of traditional institutions in Chile combined with a social environment characterized by suspicion towards strangers may explain to some degree the increasing level of credibility and familiarity afforded celebrities from both consumers and key opinion leaders. In Table 10, we can see a substantial increase in the number of characters not engaged in a specific social role ("Unidentified), i.e., characters simply posing.

With regard to the activities performed by characters (Table 11), the most significant change can be observed in fun-related activities (rising from 11.2% to 25.3%). This increase may be a reflection of lifestyle changes, and of the desires and aspirations of today's consumers, who tend to be more hedonistic. If the focus of advertising in 1997 was to provide consumers with access to a whole range of products, attention has shifted in 2013 from the "object" of consumption as the main aim of brand imagery towards the “quality of life” as the primary attribute.

Final discussion

As noted at the beginning of this article, advertising as a cultural phenomenon has the capacity to shape values and behavior by means of "interpellative" mechanisms directed at their potential consumers. It is from this perspective that advertising can be interpreted as an ideology, or rather an “ideological prêt-à-porter", constituting an interpellative system that legitimizes and validates certain social practices, whilst relating them to consumption (Vergara, 2006)3. Indeed, as proposed by Mc Quail (1991), the media as a whole, and, in this case, advertising in particular, may be regarded as just another "ideological apparatus" (p.97) as described by Althusser (1994). 4

Viewed from this cultural and ideological perspective, what then are the most apparent changes between the advertising discourse of 1997 and that of 2013? Overall, the main difference lies in the increasing representation of newly created consumer subjectivities in 2013. Comparing both periods, the advertising analyzed in 1997 (Gómez-Lorenzini et al., 2016) underscored the importance of price (which is highlighted in the texts) and the variety of products on offer (highlighted in the images), these being the key elements in the logic of consumption at that time. As such, it sought to influence the end user by means of a basic logic focused on providing access to a large quantity of low-cost goods, whose availability was still limited for the majority of Chileans.

This may be understood as a consequence of the years of deprivation experienced by a large swathes of the country's population following the economic turmoil of the 1980s, and the subsequent reaction during a decade of unprecedented abundance that followed in Chile's more recent history. It was a form of advertising aimed at developing mass consumption by offering low prices and a broad diversity of products. To advance this trend of mass consumption, advertising was informative, denotative and focused on products and discounts. Factors that might have complicated the dynamics of consumption were excluded.

Viewed from this perspective, the greater number and variety of characters featured in the ads from 2013 shows that the logic of consumption had changed. This change assumed a more active engagement of consumers, whom advertisers sought to integrate into their advertising messages; advertising had thus become rooted in a more complex social context. This situation is more in keeping with a civil society that has proven itself to be more dynamic in the country's social and political life; this is evidenced in the progressive social movements that have often taken to the streets, such as the Student Movement, reflecting a profound change in Chile’s political agenda. This stands in stark contrast to the rather passive attitude demonstrated by Chilean citizens during the 1990s (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014).

The new complexities apparent in today’s advertising discourse necessarily involve market expansion and promotion of its logic of consumption, both materially and symbolically, towards new sectors of the population. Such processes are a constituent part of the modernization discourse that has taken root since the 1990s. It is in this context, consistent with our analysis, and as a demonstration of the model's logic of expansion, that the increasing inclusion of characters from the socioeconomic middle class in advertising can be explained.

However, this would seem at odds with the high number of Caucasians represented, considering Chile’s clearly racially mixed population, in accordance with its geographic area and socioeconomic stratum. It is difficult to identify one single reason that might explain this apparent contradiction: a market that expands in one respect is at once restricted in another. As a hypothesis, one possible line of investigation could be that the position offered by advertising discourse aims to expand the current modernization model centered on consumption, but without altering its culturally symbolic essence; in other words, a western-style modernization in which aesthetic values coincide with culture norms. Therefore, when advertising displays racial, ethnic and multicultural diversity, the response has generally tended towards the "exotic" as a selling point rather than an expression of authentic diversity and tolerance towards minorities or what is perceived as “different”.

This ambiguity is also reflected in the increasingly informal depiction of characters in the advertisements analyzed: while these characters have begun to resemble more closely the average target audience; there has been an explosive growth in the number of celebrities or “faces” featured. Although, on the one hand, representation of more “ordinary” people suggests greater openness and diversification in terms of lifestyles, this pattern is eclipsed, on the other hand, by the presence of models or "showbiz" personalities who guide and steer public behavior.

We can understand these apparent contradictions to be part of the subjectivity that is inherent in the dynamics of consumption and as a reflection of the special features that have emerged in Chile's modernization process and its cultural logic. Indeed, for Lull (1997), one characteristic of the cultural dynamic at work in globalization is its capacity to recognize and absorb differences without dissolving them; rather it acts as a conduit through which this dynamic can operate.

It is this change in cultural dynamics, characterized essentially by a greater degree of subjectivity in social relations, which largely explains the shift of advertising discourse centered on product and supply in 1997, to another that seeks, by exploiting consumer subjectivity, to promote brand awareness and positioning in an ever-changing market

REFERENCES

Adam, J. M. & Bonhomme, M. (2000). La argumentación publicitaria. Retórica del elogio y de la persuasión. Madrid: Cátedra [ Links ]

Adimark. (2004). Mapa socioeconómico de Chile. Recuperado el 15 septiembre de 2014, de Recuperado el 15 septiembre de 2014, de http://www.adimark.cl/medios/estudios/informe_mapa_socioeconomico_de_chile.pdf [ Links ]

Althusser, L. (1994). Ideología y aparatos ideológicos del Estado. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión. [ Links ]

Asociación Chilena de Agencias de Publicidad-ACHAP. (2012). Inversión histórica 1978-2012. Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015, de Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015, de http://www.achap.cl/docs/ACHAP-Inv-Historica-78-2012.pdf [ Links ]

Asociación Chilena de Agencias de Publicidad-ACHAP. (2013). Inversión Histórica 2013. Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015 de Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015 de http://www.achap.cl/docs/Informe_Inv_Publicitaria_Achap_2013.pdf [ Links ]

Baudrillard, J. (1988). La sociedad de consumo. Sus mitos, sus estructuras. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (2002). Modernidad líquida. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index-BTI. (2014). BTI 2014-Chile Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. Recuperado de https://www.bti-project.org/en/reports/country-reports/detail/itc/chl/ity/2014/itr/lac/ [ Links ]

Canevacci, M. (2001). Antropologia della comunicazione visuale: feticci, merci, pubblicità, cinema, corpi, videoscape. Roma: Meltemi. [ Links ]

Caro, A. (2007). Fundamentos epistemológicos y metodológicos para un estudio científico de la publicidad. Pensar la Publicidad, 1 (1), 55-81. [ Links ]

Catalán, C. & Mella, L. (1982). El mercado de revistas de actualidad y la inversión publicitaria: el caso de Chile. Documento de Trabajo ILET DEC/D/89. Ciudad de México, México. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. & Isherwood, B. (1978). The world of goods: Towards an Anthropology of consumption. Nueva York: W.W. Norton Co. [ Links ]

Drake, P. & Jaksic, I. (Eds.). (1999). El modelo chileno. Democracia y desarrollo en los noventa. Santiago de Chile: LOM. [ Links ]

Eguizábal, R. (2007). De la publicidad como producción simbólica. En M.I. Martin & M.C. Alvarado (Coords.), Nuevas tendencias en la publicidad del siglo XXI (pp. 13-33). Sevilla: Comunicación Social. [ Links ]

Fontaine, R. (2001). Chile 2010, nuevos escenarios de la comunicación. II Congreso de Publicidad. Santiago de Chile: Asociación Chilena de Agencias de Publicidad. [ Links ]

Fraenkel, B. & Legris-Desportes, C. (1999). Entreprise et sémiologie. Analyser le sens pour maitriser I’action. París: Dunod. [ Links ]

Frith, K., Shaw, P. & Cheng, H. (2005). The construction of beauty: A cross-cultural analysis of women’s magazine advertising. Journal of Communication, 55 (1), 56-70. [ Links ]

Gómez-Lorenzini, P., Vergara, E., Porath, W. & Labarca, C. (2016). Publicidad chilena en un proceso de crecimiento económico: aspectos formales, apelaciones textuales y papeles atribuidos a los personajes en la publicidad gráfica del retail a fines de la década de 1990. Palabra Clave, 19 (1), 304-331. [ Links ]

González Martín, J. A. (1982). Fundamentos para la teoría del mensaje publicitario. Madrid: Forja. [ Links ]

Hellin, P. (2007). El uso de los valores sociales en la comunicación publicitaria: la socialización corporativa. Pensar la Publicidad, 1 (1), 157-180. [ Links ]

Henry, J. (1963). Culture against man. Nueva York: Random House. [ Links ]

Ibáñez, J. (1989). Publicidad: la tercera palabra de Dios. Revista de Occidente, 92, 73-96. [ Links ]

Jhally, S. (1987). The codes of advertising. Nueva York: St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Kang, M. (1997). The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements. Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles, 37 (11/12), 979-996. [ Links ]

Larraín, J. (2001). Identidad chilena. Santiago de Chile: LOM . [ Links ]

Lipovetski, G. (2007). La felicidad paradójica. Ensayo sobre la sociedad de hiperconsumo. Barcelona: Anagrama. [ Links ]

Lull, J. (1997) Medios, comunicación, cultura. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores. [ Links ]

Luther, C., McMahan, C. & Shoop, T. (2008). Depictions of women and men in advertisements featured in Japanese fashion magazines. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Montreal, Quebec, Canadá. [ Links ]

Mattelart, A. (1989). La internacional publicitaria. Madrid: Fundesco. [ Links ]

Mattelart, A. (1994). Los nuevos escenarios de la comunicación internacional. Barcelona: Centre del Investigació en Comunicació-Generalitat de Catalunya. [ Links ]

McCracken, X. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (1), 71-84. [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (1991). Introducción a la teoría de la comunicación de masas. Barcelona: Paidós Comunicación. [ Links ]

Moulian, T. (1997). Chile actual: anatomía de un mito. Santiago de Chile: LOM . [ Links ]

Pollay, R. W. (1986). The distorted mirror: Reflections of the unintended consequences of advertising. Journal of Marketing, 50, 18-36. [ Links ]

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo-PNUD. (2002). Nosotros los chilenos: un desafío cultural. Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas. [ Links ]

Retail Financiero. (2013, agosto) Compendio Estadístico de la Industria del Crédito. Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015 de: Recuperado el 20 de febrero de 2015 de: http://www.retailfinanciero.org/compendios/pageflip_crf_agosto_2013/documento.pdf [ Links ]

Rodríguez, J. (2002). Crecimiento económico en Chile: presente, pasado y future. Revista Economía Chilena, 5 (1), 89-95 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, X. & Mora, X. (2002). Frankenstein y el cirujano plástico: una guía multimedia de semiótica de la publicidad. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, P., Saiz, V. & Velasco, M. L. (s/f). Tratamiento de la variable género en la publicidad que se emite en los medios de titularidad pública. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer (Ministerio de Igualdad) España [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (1986). Advertising, the uneasy persuasion. Nueva York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Semprini, A. (1995). El marketing de la marca. Una aproximación semiótica. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Siavelis, P. (2009). Enclaves de la transición y democracia chilena. Revista de Ciencia Política, 29 (1), 3-21. [ Links ]

Subercaseaux, B. (1996). Chile, ¿un país moderno? Santiago de Chile: Ediciones B. [ Links ]

Tironi, E. (1999). La irrupción de las masas y el malestar de las élites. Santiago de Chile: Grijalbo. [ Links ]

Trindade, E. & Ribeiro, J. S. (2009). Antropología, comunicación e imágenes: alternativas para pensar la publicidad y el consumo en la contemporaneidad. Pensar la Publicidad, 3 (1), 203-218. [ Links ]

Vergara, E. (2003). Identidades culturales y publicidad: los usos de la cultura en la creatividad publicitaria en Chile. Trípodos, 15, 109-126. [ Links ]

Vergara, E. (2006). Publicidad: la zanahoria metafísica que mueve al burro o el color de nuestro tiempo. Trípodos, 18, 157-164. [ Links ]

Williams, R. (1999). Advertising: The magic system. En S. During (Ed.), The cultural studies reader, Second edition (pp. 410-423). Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zunzunegui, S. (1985). Televisión, el silencio de la imagen. Contracampo, 39, 16-26 [ Links ]

1A first version of this article was presented in the First Regional Conference of the Association for Education and Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) held at the School of Communications of the Pontificia Universidad Católica, Santiago, Chile, October 15-17, 2015. This paper is part of a project financed by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development, FONDECYT Chile (Project No. 1140990).

3The terms prêt-à-porter ideologique was first employed by Mattelart (1994) in the 1990s to refer to the ideological dimension of globalization, concerning the capacity of dominant thought to engage society as a whole.

4For Vergara (2006), Althusser's theory that "ideology interpellates individuals as subjects" can be applied to advertising discourse in terms of the interpellation process that operates in consumer society. This process entails the “hailing” or engagement of consumers, situating them in specific contexts, whilst enabling individuals to identify with the advertising message.

Received: May 27, 2016; Accepted: December 07, 2016

texto en

texto en