Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.29 Guadalajara may./ago. 2017

Articles

The presence of the objective method in the Chilean, Spanish and Mexican press 1

2Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, España; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile, Universidad Iberoamericana, México.

This paper analyzes the presence of the objective method in the news published by the Chilean, Mexican and Spanish press. The reporting strategies linked to journalistic objectivity predominate in the three countries. While in the Chilean and Mexican press the objective method is more present through the use of quotes, their Spanish colleagues express the objective method through the use of verifiable information.

Keywords: Journalism; objectivity; content analysis; press; cross-cultural analysis

El artículo analiza la presencia de las características del método objetivo en las noticias publicadas en diarios de Chile, México y España. El método objetivo predomina en los tres países; sin embargo, en los diarios latinoamericanos se concreta sobre todo en el uso de citas, mientras que sus colegas españoles manifiestan el empleo de la objetividad principalmente a través de la verificación de evidencias.

Palabras clave: Periodismo; objetividad; análisis de contenido; prensa; análisis comparado

Introduction

Apart from objectivity, few other elements of journalism have elicited so much debate and discussion in both the academic and professional fields. From the normative point of view, objectivity has become a shared ideal to define good journalism. Objectivity has been defined as a group of strategies (Tuchman, 1972) that journalists use to demonstrate the truthfulness of their information. These strategies or practices should be identified by the public for journalists to keep their legitimacy as communicators. This identification is channeled through the news text. For that reason, even though specialized literature has focused on the analysis of objectivity through perception of journalists-it is important to explore how the objectivity method is reflected in news content (Esser & Umbricht, 2013; Mellado &Humanes, 2015).

Moreover, the study of objectivity has revealed how journalists from different political, cultural or mediated contexts give varying degrees of importance to different strategies of the objectivity model (Donsbach & Klett, 1993; Donsbach & Patterson, 2004; Pleijter, Hermans & Vergeer, 2012; Hanitzsch & Hidayat, 2012; Oi, Fukuda & Sako, 2012; Skovsgaard Albæk, Bro & de Vreese, 2013). As Hallin and Mancini (2008) have claimed, objectivity is an indicator that serves to characterize journalism across different media systems.

In theory, the objectivity method is typical of the liberal media systems and is less common in the pluralist polarized model. Following from this rationale, and based on content analysis of Chilean, Mexican and Spanish newspapers, this article analyzes the extent to which news content reflect the strategies typical of the objectivity method. Moreover, we are interested in ascertaining the differences and similarities of the presence of such methods in the press from the three countries, since, as Esser and Umbricht (2014) claim, the variation in journalistic styles can only be adequately studied through content analysis.

This article is part of the Journalistic Role Performance Project Across the Globe, a comparative study that analyzes journalistic performance in different media systems.

Media systems in Chile, Mexico and Spain

Journalistic models in Chile, Mexico and Spain are highly connected to the development of their economic and political systems, and share important historical, cultural and sociopolitical links (Hallin & Papathanassopoulos, 2002). Throughout the twentieth century, their press development was shaped either by dictatorial and authoritarian periods in Chile and Spain, or by formal but controlled democracies in the case of Mexico, both of which discouraged the development of a liberal journalistic culture or the early development of professional standards that characterized, for instance, Anglosaxon countries (Hallin 2000a). In countries across Iberian America the political and economic conditions did not develop fully in order to guarantee press freedom, journalistic autonomy, the functioning of the press as Fourth state, the early development of objectivity as a professional canon of journalism-that is: factual and descriptive over interpretive- or the development of a media market oriented towards mass markets and readerships (Hallin & Papathanassopoulos, 2002).

Despite similarities in authoritarian periods, the three countries experienced their political transitions to different pace. Spain was the first to restore a democratic government in 1975, then Chile followed suit with the downfall of its military dictatorship in 1988 and finally Mexico did so with the electoral victory of the opposition in 2000 that ended a 70-year rule of the PRI-party hegemonic government. In the three cases, these processes were accompanied by widespread economic reforms that entailed the gradual adoption of the market economy and deregulation of sectors that allowed for the consolidation and concentration of large media consortiums (Fernández & Santana, 2000; Fox & Waisbord, 2002; Mastrini & Bolaño, 2000; Mastrini & Becerra, 2006; Sinclair, 1999).

These aspects make media systems in Latin America comparable to the Polarized-pluralist model to which Spain belongs (Hallin & Mancini, 2004). Journalism models in Spain, Chile and Mexico therefore share traits such as newspaper markets with low readerships and oriented towards politicized elites; high political parallelism; and a clientelistic political culture that favours the political instrumentalization of media owners and journalists, hence a low level of professionalization (Hallin & Papathanassopoulos, 2002; Hughes & Lawson, 2005).

Still, countries in Latin America share specific characteristics not completely compatible with the Polarized Pluralist Model proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2008). Guerrero and Márquez (2014) propose to see the media systems in Latin America not as an extension of the Polarized-pluralist model, but instead as ‘liberal-captured’ models. They argue that in the highly concentrated, private media models of media systems, a clientelistic culture functions as the engine of an extensive machinery for the exchanging of favours and benefits, for example: positive coverage of political leaders in exchange of extensions to broadcast licenses. This exchange would not always qualify as formal political instrumentalization or State intervention, but instead as an informal capture of the monitorial function of the media, and therefore of their watchdog role on the part of private interests, be it political or economical. Following these arguments about deviant media systems in Latin American in regard to the Polarized-pluralist model, it is therefore important to see the differences and similarities between Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) variables of such model, and those of the three countries in this study. These characteristics could shape and explain journalists’ use of objective reporting methods.

Spain clearly fits within the Polarized-pluralist model. First of all, it shows a late development of the press market that resulted in low readerships and elite-oriented content; second, there is a high political parallelism that is reflected in the external pluralism and in both media and audiences’ partisanship; third, there is high state intervention in broadcast and parliamentary regulation, and fourth, we find a low level of journalistic professionalization and limited autonomy (Brüggemann et al 2014; Humanes, 2014; Martínez, Humanes & Saperas, 2014).

The two Latin American countries coincide with Spain in the low readerships and elite orientation of their presses, as television is still the main source of information for the public. However, in Chile and Mexico there is also a popular-press tradition not developed in Spain (Hallin 2000b). Moreover, Mexico and Chile developed their media system after the private, liberal model of the United States and have a highly concentrated broadcasting market (Fox & Waisbord, 2002). In the case of Chile, the dictatorial rule experienced quite early with the market economy, hence becoming a political dictatorship with a neoliberal economy. The specific consequences for the media are the consolidation of a neoconservative media elite that originally served as the façade and legitimating channel for the regime and its abuses (Muzinaga, 1982). Later on, Chilean media gradually opened their critical spaces to the regime during the process of democratization (Tironi & Sunkel, 2000) and more recently the media combined a political conservative type of journalism but at the same time oriented towards entertainment (Mellado & Lagos, 2014). For its part, Mexico displays a highly concentrated media system with few key players and a great deal of dependence on the part of small and medium media on the steady income of political and governmental advertising (Hughes, 2009). Also, it is often still the case, there is a negotiation of news coverage and conditioning of political support in electoral periods (González Macías, 2013; Márquez Ramírez, 2014).

In the three countries we find a low level of professionalization and high instrumentalization (Hallin & Mancini, 2008; Hallin & Papathanassopoulos, 2002), as a result of the profession not establishing itself as an autonomous field with its own standards, but functioning as the ideological tool for the factions in quest for power (Lombardo, 1992).

Finally, there is a high level of political parallelism in the three countries, but with important and differentiated nuances. In the Spanish case, media partisanship responds to clear ideological positions on the part of organizations and journalists that resonate with those of their audiences. In contrast, in Chile and Mexico we find a different situation. The media structure corresponds to clearly conservative political and economic interests in the case of Chile, whereas in Mexico we find a ‘market-driven partisanship’ (González Macías, 2013; Guerrero, 2004; Hughes, 2009). Furthermore, audience partisanship in the Latin American countries is not as sharp as is in the Spanish case.

Considering these similarities and differences, the article compares the presence in news content of the characteristics of the objectivity method in the press from Spain, Chile and Mexico. Results will help corroborate whether media systems from Latin America, said to akin to the Pluralist Polarized model, follow patterns similar to those of Spain, or, whether the Mexican and Chilean press depart from their Spanish counterpart.

The implementation of objectivity in the news

Even though historically, objectivity has been a cornerstone of professional journalism in Anglo-Saxon journalistic cultures (Hallin, 2000a; Schiller, 1979; Schudson, 2001; Tuchman, 1972) it has spread beyond borders to influence the professional practice around the world (Weaver & Willnat, 2012).

As a reporting method, objectivity has been operationalized in a number of strategies that journalists use to produce information and legitimate their autonomy in relation to editorial or partisan interests (Benson, 2006; Kovach y Rosenstiel, 2007; Mindich, 1998; Tuchman, 1972; Waisbord, 2006). Tuchman (1972), for instance, defined objectivity as a “strategic ritual” that includes diverse practices such as fact verification and accuracy, presentation of conflicting possibilities, presentation of supporting evidence, the judicious use of quotation marks and the structuring of information in inverted pyramid style. Thus, reporting practices considered as “objective” have been the method utilized by journalists to prove their truthfulness about reality. The characteristics of the objectivity method are, therefore, reflected in the news and able to be examined through news content analysis to examine the level of engagement on the part of news authors with the objectivity method.

In fact, literature has focused mainly in analyzing journalists’ perceptions of objectivity as a reporting method than on how it is materialized in news content. In other words, research has preferred to measure the extent to which journalists assign importance to objectivity in relation to other ways to represent reality, than in to probe how such method of objectivity in the news conveyed to the public. However, there have been calls to use content analysis to understand journalistic cultures beyond the mere perceptual level (Esser & Umbricht, 2014).

Esser and Umbricht (2013, 2014) have empirically analyzed how the different characteristics of objectivity manifest themselves in news content. They used five indicators to measure the methods of the objectivity method for their comparative analysis of newspapers from United States, Great Britain, Germany, Switzerland, France and Italy, namely: presentation of contrasting viewpoints, use of experts, use of quotations, inverted pyramid and formal separation between facts and opinion. Their findings reveal that the objectivity method prevailed in countries pertaining to the liberal media system and to a lesser extent in countries pertaining to the Pluralist Polarized Model.

With respect to the three countries in this study, journalists have showed, at least at the perceptual level, their adherence to objectivity with certain nuances. In Spanish journalism, Canel (1997) analyzed the notions of objectivity in two TV networks during an electoral campaign, finding that even though in public-service broadcasting journalists declared their attachment to the classic norm of objectivity, in private television news-writers opted for a more analytical coverage. Through in-depth interviews with journalists from El Mundo, Berganza, Oller and Meier (2010) concluded that objectivity is not strictly applied, giving more importance to the use of quotations and to the presentation of all the participating sides of the events, than to other strategies of the objective method such as verifiable facts, inverted pyramid or separation between information and opinion.

In Chile, Mellado, Moreira and Hernández (2012) found that the aspects of objectivity most important to journalists are: to not to let opinions and beliefs interferes with news work (54.5% of interviewees strongly agreed), to stay impartial (49.5%) and to use reliable evidence and sources (46%). Surveyed journalists gave little relevance to the idea that facts speak for themselves (18%) and to the possibilities to present reality as it is (16.2%).

In Mexico, that similarly study (Mellado et al, 2012) revealed that journalists associate the objective method mainly to the strategies of supporting news with reliable evidence and sources (65%), to not let opinions and beliefs to interfere with work (55%), to be impartial (54%) and to let facts speak for themselves (48%).

In Chile, Mexico and Spain, however, the studies of how objectivity materializes in news content are scarce.

In the Chilean case, Mellado and Humanes (2015) conducted a content analysis of the objective method in political information between 1990 and 2010, measuring four indicators: balance, verifiable evidence, quotations and the use of the inverted pyramid. The research showed that the objectivity method was, with great difference, the most used by the Chilean print press, although more analytical strategies such as argumentation, the use of conditional and the inclusion of judgmental values had increased towards a more partisan style in the past 20 years. Specifically, the reporting method more widely found was the use of inverted pyramid, followed by the use of quotations, and later by the use of verifiable evidence and hard facts. The last used resource, in contrast, was the presentation of diverse viewpoints.

As for Mexico, Hughes’ (2009) study of the presidential campaigns in 2000 measured the diversity and balance in the coverage of political parties and actors in five newspapers. She found that the press slightly favoured the voices of the regime (17.1 per cent of the sample) in relation to the voices of the opposition (15.5%). Also, she found that two out every three articles presented a single perspective. Twelve years later, for the 2012 presidential elections, a study of 16 newspapers around the country (Martínez Garza, 2013) also measured fairness, finding that the PRI candidate gained considerable more coverage than any of the two other candidates in all the selected papers, even though the percentages varied across regions and organizations.

In the case of the Spanish press, there exist some investigations that indirectly study objective reporting in journalistic performance. Strömback and Luengo (2008) measured descriptive versus interpretative in Spanish and Swedish press during electoral campaigns, finding that 61.3% of information in Spain fitted the descriptive style. Meanwhile Martínez, Humanes and Saperas (2014) also analyzed the presence of the descriptive style in El País and ABC newspapers from 1980 to 2010, concluding that its major predominance (60%).

As we can observe, comparative literature in the Ibero-American region and Spain is scarce with regards to the measurement of the strategies of objectivity in news content. However, due to differences and similarities between countries in Latin America and those in both the Liberal and the Pluralist Polarized model, and also due to their own journalistic cultures, it is important to analyze whether objectivity, beyond being a merely discursive resource on the part of the journalist, manifests itself in news addressed to the citizens.

With this rationale in mind, we pose the formal research question: what characteristics of the objective reporting method predominate in news content in the Spanish, Chilean and Mexican press?

Methodology

To answer our research questions, we performed a quantitative content analysis of news items published in the Mexican, Chilean and Spanish presses in 2012 and 2013 based on standardized operationalization of reporting methods (Donsbach & Klett, 1993; Esser & Umbricht, 2013; Mellado & Humanes, 2015).

In each country, between three and four nationally distributed general interest print media were analyzed (see Table 1). The bases for selecting these newspapers were their market orientation - elite vs popular - and their political orientation. The characteristics of the selected newspapers therefore vary depending on each media system. Despite the development of new digital media and the advent of social media, the print press continues to be an influential news channel when it comes to agenda setting for other media (Espino-Sánchez, 2011).

El Mercurio, La Tercera, Las Últimas Noticiasand La Cuarta were included in the analysis for Chile. El Mercurio and La Tercera are Chile’s main elite newspapers - the former is more conservative in its leaning while the latter is rather more liberal. Las Últimas Noticias and La Cuarta (which belong to El Mercurio and Copesa, respectively) are popular newspapers with a patent commercial model.

Two of the most important nationally distributed quality newspapers and one tabloid newspaper were analyzed for Mexico. The first is La Jornada, with a progressive editorial line and a centre-left leaning. The second is Reforma, with a centre-left business leaning, aimed at the urban middle class. The third, La Prensa, has a centre-pro-government leaning and a rather more sensationalist orientation. It is one of the highest circulation newspapers in the country.

El País, El Mundo, La Razón and ABC were analyzed for Spain. These newspapers were selected because they represent different ideological tendencies. The audiences of the four publications display a high degree of ideological parallelism with the newspapers they read. El País is the only centre-left newspaper. ABC and La Razón are conservative and highly pro-monarchy newspapers. El Mundo is right leaning politically and liberal leaning economically.

Although the samples in the three countries are not homogeneous, due to the fact that the popular press does not exist in Spain, we have decided to select a sample that represent the characteristics of the newspaper market and not force them for comparison. Nevertheless, as findings show, all statistical tests run fur this study have been replicated removing the Chilean and Mexican popular items from the sample, finding no significant differences with the actual results using the entire sample, except for one of the variables.

The period analyzed was January 2, 2012 to December 31, 2013. Using the constructed week method, a stratified systematic sample was selected for each newspaper. From each newspaper, a Monday, a Tuesday, a Wednesday, a Thursday, a Friday, a Saturday and a Sunday were selected for every semester of each year. We ensured that every month was represented by at least one day, thus preventing an over-representation of a particular period.

The unit of analysis was the news item, understood as a group of continuous verbal or visual elements referring to the same topic. For each selected issue of a newspaper, all news items connected with the national and or/country sections.

Three coders in Chile, six coders in Mexico and four coders in Spain were trained in how to apply the common codebook. Krippendorff’s alpha was used to test inter-coder reliability. Based on the Ka formula, intercoder reliability was .78 for Chile, 0.76 for Mexico and .72 for Spain.

A total of 2,582 news items from the Chilean press were analyzed, as were 3,009 from the Mexican press and 2,277 from the Spanish press.

Measurements

To analyze the use of different objective reporting methods in Chilean, Mexican and Spanish journalism, we followed from previous studies that have conducted news content analysis to measure the implementation of the objectivity method in news texts (Esser & Umbricht, 2013; Mellado & Humanes, 2015, Ward, 1999).

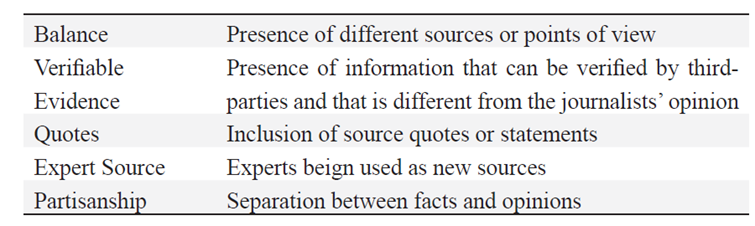

In total, five indicators were used: balance, verifiable evidence; citations; use of expert sources and partisanship. Table 1 presents the operational definitions of each indicator, coded on a presence/absence binary base.

To answer our research question we have conducted bivariate statistical analysis (cross tabs) and analysis of adjusted standardized residuals.

Findings

The presence of objective reporting methods predominates in the printed press in Chile, Spain and Mexico, with the exception of balance and the use of experts. The low presence of diverse points of view in the information is one of the basic characteristics of journalistic contexts with a strong tradition of conservative press (in the case of Chile), passive-official press (in the case of Mexico) and partisan press (in the case of Spain). Similar to the findings from previous research by Mellado and Humanes on the Chilean political press (2015), the percentage results show that the liberal objective reporting method is reinterpreted by Latin American and Spanish press, which plays down the importance of presenting diverse points of view and of the use of expert sources.

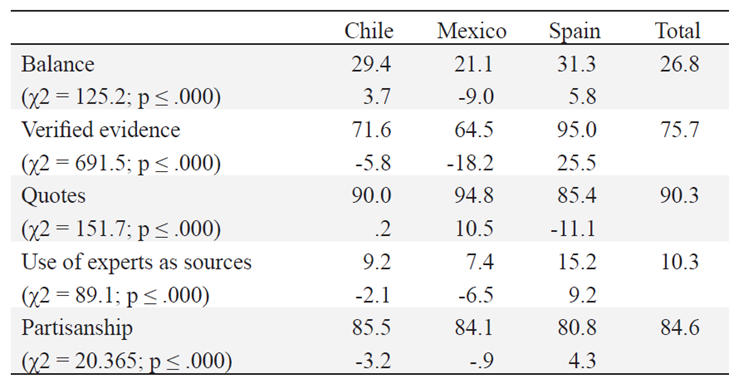

However, a statistical analysis of adjusted standardized residuals shows that this tendency manifests itself differently in each of the three cases (see Table 2). Comparatively, Chile and Spain stand apart from Mexico because they have a higher presence of different points of view in the news. In contrast, regarding the use of other strategies associated with the objective method analyzed in this study, the Latin American press manifests greater uniformity. Chilean and Mexican journalists use less verifiable evidence and fewer experts as sources than their Spanish peers. However, the Chilean and Mexican press manifests a higher use of quotes in general (see Table 2).

Table 2 Presence of objective method strategies (% and standardized residuals)

Source: Authors’ own elaboration

A possible explanation is that these differences could be due to the absence of the popular press in the Spanish sample. To rule out any distortion in the results that might be due to this fact, we proceeded to perform the same analysis by excluding the Chilean and Mexican popular newspapers, and no significant differences were found, except for the separation between information and opinion (partisanship). In that case, Mexican elite newspapers are more like Spanish newspapers that mix information and opinion (21.1% and 19.2%, respectively), whereas in Chile, that characteristic is inherent to the popular press (29.7%).

Conclusions

The study analysed the presence of strategies associated to objective reporting in news from the Chilean, Mexican and Spanish press. Global data show that the strategies of the objectivity method more present are the use of citations (90.3%), separation between facts and opinion (86.4%) and verifiable evidence (75.7%).

The strategies that are the least present, in global terms, are balance and the use of experts and news sources. The three countries share the low presence of balance (26.8% for the total sample), confirming the importance of political parallelism in media systems across the three countries, in accordance to the Pluralist Polarized Model proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2008). In the Spanish case, the clear ideological alignment of the media explains that the reporting of diverse points of view is a limited resource in the implementation of objectivity. In the case of Chile, this result could respond to the links between media elites and the political and economic interests. Similarly, for Mexico, this finding also reflects a tendency towards prioritization of official sources that runs in parallel to its presidential type of government.

Another common result in the three countries is that the use of expert sources is only present in 10% of the sample. This result resonates with Esser and Umbritch (2013)’s comparative study, which found that newspapers from the Polarized-Pluralist model (Italy and France) turn to expert sources in much lower extent than journalists from other types of media systems.

However, when the three countries are compared, results show two ways of implementing the objectivity norm in new content. For Latin American journalists, the objective method concentrates primarily on the use of quotes, while their Spanish counterparts express the norm mainly through verifiable evidence. In that sense, the argument that journalistic traditions and social contexts shape the materialization of objectivity is supported. In Spain, a more militant tradition like the one existing in the Polarized-Pluralist model would force journalists to legitimate the use of “verified facts” over opinions to distance themselves from that tradition. In Chile, the use of quotation marks could be the means that journalists use to distance themselves from their source’s stances and from their medium’s editorial policies, or in other words, legitimate their autonomy. In the case of Mexico, the results reflect a journalistic tradition closely connected to the visibilization of the political elites and a reporting culture based on the prevalence of ‘statement-only’ stories gathered from a ‘quotes today, counter-quotes tomorrow’ type of chain.

The Mexican and Spanish press also share a similar presence of the strategy that separates facts and opinion (partisanship). Spanish journalists tend to include more opinions when they inform.

The results of this study have important implications for the understanding of Ibero-American media systems. While journalistic traditions in Latin America could share some characteristics with culturally close countries such as Spain, they have particularities that may shape the differences on the materialization of the objective reporting, as revealed by our study. Furthermore, results also offer interesting insights about how, due to a wide variety of endogenous and exogenous circumstances, journalistic norms, such as objectivity, may be internalized at the rhetorical level, but not to the performative level, where the practice of reporting techniques associated to objectivity such as quotes, balance, the use of expert sources, separation between facts and opinions, and the use of verifiable evidence vary considerably across the countries in this study.

In that sense, results reveal that the analyzed countries cluster in two blocks depending on the presence of the diverse strategies of objective reporting to give legitimacy to the truthfulness about reality. In the first block, we find that Chilean and Mexican newspapers share similar levels of verifiable evidence, cites, expert sources and separation of facts and opinions. Spain, on the other hand, departs from the Latin American countries due to a higher presence of verifiable evidence, use of experts, news mixing information and opinion and less use of direct quotes.

In conclusion, the study of objectivity through content analysis has been a useful research approach to illuminate differences and similarities across journalistic cultures.

Despite these findings, there is need of further empirical research, not only to ascertain whether journalists from different traditions adhere to the objectivity norm, but also to determine the meaning attributed to objectivity, and the way in which they learned to put it into practice. The possible areas for future research could include comparative analysis of journalism education and news-making techniques.

Future studies could also compare the results of the Ibero-American presses, with the analysis of other media platforms, such as television, radio, online or social media news, in order to corroborate differences and similarities in the implementation of the objectivity norm in news content across platforms.

REFERENCES

Benson, R. (2006). News media as a “journalistic field”: What Bourdieu adds to new institutionalism, and vice versa. Political Communication, 23 (2), 187-202. [ Links ]

Berganza, R., Oller, M. & Meier, K. (2010). Los roles periodísticos y la objetividad en el periodismo político escrito suizo y español. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 65, 488-502. [ Links ]

Brüggemann, M., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Humprecht, E. & Castro, L. (2014). Hallin and Mancini Revisited: Four empirical types of Western media systems. Journal of Communication, 64 (6), 1037-1065. [ Links ]

Canel, M. J. (1997). La objetividad periodística en campaña electoral: las actitudes profesionales de los periodistas de TVE1 y Antena3 en las elecciones de 1996. Zer: Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 2, 55-70. [ Links ]

Donsbach, W. & Klett, B. (1993). Subjective objectivity. How journalists in four countries define a key term of their profession. International Communication Gazette, 51 (1), 53-83. [ Links ]

Donsbach, W. & Patterson, T. (2004). Political news journalists: Partisanship, professionalism and political roles in five countries. En F. Esser & B. Pfetsch (Eds.), Comparing political communication: Theories, cases, and challenges (pp. 251-270). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Espino-Sánchez, G. (2011). La transformación de la comunicación política en las campañas presidenciales de México. Convergencia, 18 (56), 59-86. [ Links ]

Esser, F. & Umbricht, A. (2013). Competing models of journalism? Political affairs coverage in US, British, German, Swiss, French and Italian newspapers. Journalism, 14 (8), 989-1007. [ Links ]

Esser, F., & Umbricht, A. (2014). The evolution of objective and interpretative journalism in the western press comparing six news systems since the 1960s. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 91 (2), 229-249. [ Links ]

Fernández Alonso, I. & Santana, F. (2000).Estado y medios de comunicación en la España democrática. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Fox, E. & Waisbord, S. (2002). Latin politics, global media. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

González Macías, R. (2013). Economically-driven partisanship, official advertising and political coverage in Mexico: The case of Morelia. Journalism and Mass Communication, 3 (1), 14-33. [ Links ]

Guerrero, M. A. (2004). La apertura de la televisión privada en México. Política y Sociedad, 41 (1), 89-93. [ Links ]

Guerrero, M. A. & Márquez-Ramírez, M. (2014). Media systems and communication policies in Latin America. Londres: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. (2000a). Commercialism and professionalism in the American news media. En J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (Eds.), Mass media and society (pp. 218-237). Londres: Arnold. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. (2000b). La nota roja: Popular journalism and the transition to democracy in Mexico. En C. Sparks & J. Tulloch (Eds.), Tabloid tales: Global debates over media standards (pp. 267-286). Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. & Mancini, P. (2008). Sistemas mediáticos comparados: tres Modelos de relación entre los medios de comunicación y la política. Barcelona, España: Hacer. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. & Papathanassopoulos, S. (2002). Political clientelism and the media: Southern Europe and Latin America in comparative perspective.Media, Culture and Society, 24 (2),175-195. [ Links ]

Hanitzsch, T. & Hidayat, D. (2012). Journalists in Indonesia. En D. Weaver & L. Willnat (eds.), The Global Journalist in the 21st Century (pp. 36-51). Nueva York: Routledge [ Links ]

Hughes, S. (2009). Redacciones en conflicto: el periodismo y la democratización en México. México: Porrúa. [ Links ]

Hughes, S. & Lawson, C. (2005). The barriers to media opening in Latin America. Political Communication, 22 (1), 9-25. [ Links ]

Humanes, M. L. (2014). Selective exposure and partisanship among audiences in Spain: Consumption of political information during election campaigns: 2008 and 2011. Palabra Clave, 17 (3), 773-802. [ Links ]

Kovach, B. & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect, completely updated and revised. Nueva York: Random House. [ Links ]

Lawson, C. (2002). Building the fourth estate: Democratization and the rise of a free press in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Lombardo, I. (1992). De la opinión a la noticia. México: Ediciones Kiosko. [ Links ]

Márquez-Ramírez, M. (2014). Post-authoritarian politics in a Neoliberal Era: Revising media and journalism transition in Mexico. En M. A. Guerrero & M. Márquez-Ramírez (Eds.), Media systems and communication policies in Latin America (pp. 272-292). Londres: Palgrave Macmillan . [ Links ]

Martínez, M., Humanes, M. L. & Saperas, E. (2014). La mediatización de la política en el periodismo español. Análisis longitudinal de la información política en la prensa de referencia (1980-2010). Trípodos, 34 (1), 41-59. [ Links ]

Martínez Garza, F. (2013). La contienda electoral federal en la prensa mexicana. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública (julio/diciembre), 61-79. [ Links ]

Mastrini, G. & Becerra, M. (2006).Periodistas y magnates: estructura y concentración de las industrias culturales en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Prometeo. [ Links ]

Mellado, C. & Humanes, M. L. (2015). The use of objective and analytical reporting as a method of professional work: A cross-longitudinal study of Chilean political coverage.The International Journal of Press/Politics, 20 (1), 67-84. [ Links ]

Mellado, C. & Lagos, C. (2014). Professional roles in news content: Analyzing journalistic performance in the Chilean National Press. International Journal of Communication, 8, 2090-2112. [ Links ]

Mellado, C., Moreira, S. V., Lagos, C. & Hernández, M. E. (2012). Comparing journalism cultures in Latin America The case of Chile, Brazil and Mexico.International Communication Gazette, 74 (1), 60-77. [ Links ]

Mindich, D. T. (1998). Just the facts: How objectivity came to define American journalism. Nueva York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Munizaga, G. (1982). Políticas de comunicación bajo regímenes autoritarios: el caso de Chile. En E. Fox & H. Schmucler (Eds.), Comunicación y Democracia en América Latina (pp. 41-68). Lima: Centro de Estudios y Promoción del Desarrollo/Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales. [ Links ]

Oi, S., Fukuda, M. & Sako, S. (2012). The Japanese journalist in transition: Continuity and change. En D. Weaver & L. Wilnat (Eds.), The Global Journalist in the 21st Century (pp. 52-65). Nueva York: Routledge [ Links ]

Pleijter, A., Hermans, L. & Vergeer, M. (2012). Journalists and journalism in the Netherlands. En D. Weaver & L. Wilnat (Eds.), The Global Journalist in the 21st Century (pp. 242-252). Nueva York: Routledge [ Links ]

Schiller, H. (1979).Los manipuladores de cerebros. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (2001). The objectivity norm in American journalism. Journalism, 2 (2), 149-170. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. (1999). The Autumn of the patriarch: Mexico and Televisa. En J. Sinclair (Ed.), Latin American Television: A Global View (pp. 33-62). Nueva York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Skovsgaard, M., Albæk, E., Bro, P. & De Vreese, C. (2013). A reality check: How journalists’ role perceptions impact their implementation of the objectivity norm. Journalism, 14 (1), 22-42. [ Links ]

Strömbäck, J. & Luengo, O. (2008). Polarized pluralist and democratic corporatist models: A comparison of election news coverage in Spain and Sweden.International Communication Gazette, 70 (6), 547-562. [ Links ]

Tironi, E. & Sunkel, G. (2000). The modernization of communications: The media in the transition to democracy in Chile. En R. Gunther & A. Mughan (Eds.), Democracy and the media: A comparative perspective (pp. 165-194). Cambridge, Inglaterra: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tuchman, G. (1972). Objectivity as strategic ritual: An examination of newsmen’s notions of objectivity. American Journal of Sociology, 77 (4), 660-679. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2006). In journalism we trust? Credibility and fragmented journalism in Latin America. En K. Voltmer (Ed.), Mass media and political communication in new Democracies (pp. 76-91). Londres, Inglaterra: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ward, S. (1999). Pragmatic news objectivity: Objectivity with a human face. Discussion Paper D37. Cambridge: Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government. [ Links ]

Weaver, D. & Willnat, L. (2012). The Global Journalist in the 21st Century. Nueva York: Routledge [ Links ]

Received: June 23, 2016; Accepted: November 22, 2016

texto en

texto en