Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicación y sociedad

versão impressa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.29 Guadalajara Mai./Ago. 2017

Articles

Electoral campaign on the Internet: Planning, impact and viralization on Twitter during the Spanish general election, 2015 1

2Universidad de Valladolid, España. Correo electrónico: eva.campos@hmca.uva.es

*Universidad de Valladolid, España. Correo electrónico: dafne.calvo@uva.es

This study focuses on the partisan use of Twitter in the Spanish general election, 2015. The aim is to assess whether the strategy designed by the parties is equivalent to the result in terms of viralization. Methods used to study this social media were interviews to campaign managers and content analysis of messages published on the Net. The results show that electronic strategy on Twitter is not successful when traditional media impact is not considered.

Keywords: Political communication; election campaign; Internet; Twitter; Spain

Este estudio se centra en el uso partidario de Twitter en las elecciones generales de 2015, en España. El objetivo es conocer si la estrategia y planificación diseñada por los partidos tiene equivalencia con el resultado, en términos de viralización. Como método se aplican entrevistas a responsables de campaña y un análisis de contenido de los mensajes publicados. Las conclusiones permiten detectar que la estrategia en Twitter no resulta exitosa si no se considera la repercusión mediática tradicional.

Palabras clave: Comunicación política; campaña electoral; Internet; Twitter; España

Introduction

Since the onset of political cyber-communication, digital tools have been used by party organizations, at least in the Spanish case, as a complementary rather than as an effective element in the struggle for capturing public opinion and mobilizing the electorate (Sampedro, 2011), following on the Internet the schemes of the communicative strategy of traditional influenced politics (Casero Ripollés, Feenstra & Tormey, 2016; Mazzoleni, 2001; McChesney, 2015; Norris, 2000; Ward, Gibson & Lusoli, 2008). It became evident how the parties had been replicating, in the digital campaign, the same strategies of the offline campaign, failing to take advantage of the potential that digital tools could offer to the new campaign by means of a change in mentality in the design and planning of online campaigns (Schweitzer, 2008, 2011; Strandberg, 2008).

In the first decade of the 21st century, with the boom of social networks, the first “Internet candidates” emerge who showed that the use of the cyberspace in the campaign could make a great media impact (Vaccari, 2010). It was Obama, with his 2008 campaign, who proved for the first time that the “Internet candidate” could not only make a media impact but also win the elections (Barron, 2008; Dader, 2016; Delany, 2009; Hendricks& Denton, 2010; Iglesias, 2012; Moceri, 2012, Smith, 2010). Although at first the success of the Obama campaign was attributed to the mass use of social networks, later research proved that the key lay in the global strategy of his campaign, as a revitalizing, coordinating element of the entire communicative process, considering network mobilization and collaboration of sympathizers and volunteers as the key (Delany, 2009).

This way, the new online party campaign strategies would take two crucial approaches as the axis: a) on the one hand, technology as a base campaign tool to articulate messages aimed at mobilizing sympathizers and volunteers (Sánchez Duarte & Magallón, 2016) and thus dominate the digital communicative space, replicating party messages with a large number of volunteers/emitters on the Web -instead of opting for the use of social media only as a fashion or a complement of traditional self-promotion communication, restricting the role of the emitters only to the traditional political and media elites-; b) on the other hand, designing strategies to find citizens in the data (Kreiss, 2015), combining the different information flows that political parties have about the users by means of “profiling” (Mattelart & Vitalis, 2015) or profile information about social network, email, online request users, etc., hiring these services from companies (Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc.) (McChesney, 2015), to try to establish the citizens’ political affinities and allow articulating messages à la carte, as defined by Kreiss (2015), “retail-like”.

To date, the results obtained by the most recent research in the Spanish context, in which this study is framed, show that though the Web remains as a non-strategic tool, political parties are developing election organization and mobilization tactics through Telegram groups (case in point, the political party Podemos), internal platforms such as Eco en Red (in the PSOE) or their own software, such as Calisto Live, the Partido Popular, which provides large-scale data for the candidates when they hold a rally, attend a public act or participate in a TV debate (Redondo & Calvo, 2016). All of this also includes buying data from Facebook, Twitter or Google to plan segmented or “à la carte” campaigns, on the part of Spanish political parties.

In this sense the key does not only lie in the contents and the impact and diffusion of social networks and digital tools used by the political parties on a campaign, but precisely in the articulation between the design of the strategies by the party organizations in the online campaign and the effects attained in the actual use of these tools. This research pursues this objective, which explores how the 2015 election campaign has been designed on the Internet by four Spanish political parties and how they have used a social network in particular: Twitter.

The importance of Twitter as an election campaign tool originates in Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential race, as a political communication tool with two main functions: announcing the campaign acts and redirecting the voters to specific contents on their webpage (Solop, 2010). These strategies were later transferred to Europe, where works like those by Graham, Broersma, Hazelhoff and van't Haar (2013) conclude that candidates use the tool as a unidirectional form of communication and only exceptionally for mobilization or consultation.

In Spain, the 2011 general elections begin the research on this social network, even though there had been previous studies that analyzed regional contexts such as the Catalan to use the debate produced as public opinion estimations from another perspective (Congosto, Fernández & Moro Egido, 2011). In the case of the national elections, Borondo, Morales, Losada and Benito (2012) confirm that the activity on Twitter is related with the election results and the debate is scant, since stratified attention is focused on specific profiles, as ratified in López-García (2016). The present research focuses on the study of the online campaign strategies by six Spanish political parties, and their corresponding main leaders, in the specific context of the General Elections in Spain on December 20th, 2015.

It has set two specific objectives: a) on the one hand, getting to know the organizational structure and planning to set out the cyber-campaign strategy that the main Spanish political parties developed in the process for the general elections on December 20th, 2015 for the social tool Twitter and b) on the other hand, analyzing the repercussion and viralization -ultimately, the success- of the messages posted by these political parties on this network, observing the subject matter of the discourses to detect whether there is prevalence of the contents related in each of the campaigns analyzed with political/institutional, social, general politics information, or else whether the party’s political or program proposals are prioritized instead of personalistic or entertainment issues, election campaign issues or ideological-propaganda contents.

Ultimately, the final goal is to know whether the election campaign designed and carried out by the Spanish political parties on the Internet, on Twitter in particular, corresponds with the success attained by this social network in terms of audience, viralization and topics of these messages.

In view of these objectives, two main hypotheses are formulated:

H1. Political parties are planning their digital campaigns following the traditional model, in the light of the communication strategy.

H2. The party messages on Twitter that are the most viral and have the most repercussion are those that the parties also design for diffusion on other traditional media.

Methodology

In order to attain the objectives set and prove the hypotheses set forth in the previous paragraph, a two-fold approach is proposed: the qualitative and the quantitative ones, using in-depth interviews and content analysis as the method.

Firstly, with the objective of knowing what the design and planning of the parties’ online campaign is, 11 in-depth interviews were conducted with the people responsible for the digital campaign of the following party organizations: Partido Popular (PP), Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), Podemos, Ciudadanos, Izquierda Unida (IU) and Unión, Progreso y Democracia (UPyD). All the people responsible for the campaign were interviewed twice (once before and once after the elections), with the exception of Ciudadanos, since in this case in particular only the post-election interview was possible. Systematized interviews turned out to be the most appropriate procedure to obtain internal information about the organizations and thus know the opinions and beliefs held by the people responsible about the value and use of the digital media, especially that of Twitter. The interviews were performed in the six months prior and subsequent the elections, each of them were conducted by two interviewers who had been previously trained, and they were carried out in the framework of the research project “Online campaign strategies of Spanish political parties: 2015-2016”.

Secondly, to the end of analyzing the most viral and influential messages posted on Twitter during the campaign, the method chosen was that of content analysis, preceded by a descriptive and contextual statistic analysis of the data obtained with computer software. They are considered to have great complementary value, due to their scope in terms of the sheer number of messages generated and the number of users who participated, the most relevant tweets around the hashtags, as well as the collection of the main quantitative magnitudes of the activity, the type of content, authorship and the interaction registered on Twitter by the parties’ and their leaders’ accounts.

The sample selected for this study, therefore, focuses on the Twitter accounts of the following parties and leaders: Partido Popular (@PPopular and @marianorajoy); Partido Socialista (@PSOE and @sanchezcastejon), Podemos (@ahorapodemos and @Pablo_Iglesias_), Ciudadanos (@CiudadanosC and @Albert_Rivera), Izquierda Unida (@iunida and @agarzón) and Unión, Progreso y Democracia (@UPYD and @Herzogoff). The dates in which the samples were collected covers the election campaign days, the reflection day, Election Day and the three following days. This way, from December 4 to December 23, 2015 19.881 tweets were collected, they were recorded using the tool T-hoarder to monitor the data on this social network. For this sample, messages surpassing 1000 retweets were selected.

The application of a content analysis allows greater delving in specific messages and users in terms of number of messages generated and the number of the users that participate, the most relevant tweets around the hashtags, as well as the collection of the main quantitative magnitudes for the activity, the type of content, authorship and the interaction registered on Twitter by the parties’ and leaders’ accounts. To this end, once again we used the book of codes designed in the framework of the research project “Online campaign strategies of Spanish political parties: 2015-2016”, based on Muñiz, Dader, Téllez and Salazar (2016). In the category “Political Framing of the content of posts/tweets” the following frames were included: “Personalistic and emotional appeal frame”, “strategic game frame”, “political stand news topic frame”, “logistic-mobilizing frame”, “pedagogic or didactic frame” and “frame for the Invitation/Incitation to the media follow-up”. This was the scheme followed when it came to analyzing the thematic content of the most retweeted messages.

Results

Design of the party campaign on Twitter

The election campaign on Twitter, just like the rest of the digital campaigns, was planned and developed by most of the parties analyzed from one department or area of their own, or in more or less coordination with other party areas, mainly with the press cabinets or departments, although with differences among the parties: PP, PSOE, Podemos and Ciudadanos have a specific department of their own for these undertakings that remain in place during the entire term, regardless of whether elections are held or not, and they have autonomy from the communication cabinet; others, like IU and UPyD manage their communication on networks under the supervision or coordination of the press cabinet. The exception to the rule is UPyD, where digital political communication has been managed wholly by the same general communication team: for the December 2015 elections “there was a very small communication department, smaller than the one before, but we have especially focused on digital communication” (Sic., UPyD interviewee).

The structure of the organizational charts in these departments and teams also depends on the case: in contrast with clear structures, with well-defined tasks dedicated to the analysis and creation of contents, such as the one described by the Partido Popular, PSOE or Podemos, there are others that are more diffused or recent such as Izquierda Unida of UPyD. In this sense, Izquierda Unida’s online team calls our attention:

Ours is a very curious origin … it was almost a call for help, because we understand that the 20D campaign was a very hostile campaign for our party … then we designed a communication strategy, that is somewhat in keeping with the one we have now, which in addition has gone from the digital to the non-digital world … which arises out of necessity, because we understood that there was very little political space for our party, we then called out for help to the members of our organization, those who either do this professionally in their private lives or work in other areas of the organization but are very good at it, then we put together a group of ten or twelve people, who came to Madrid during the election campaign and the La Cueva was born, coordinated through me personally (interviewee), I am the executive secretary for communication and I coordinate both the press cabinet’s and La Cueva’s work (Sic., IU interviewee).

Along the same line, depending on their professional profile, regardless whether the parties observed had a department of their own or not, this research is interested in knowing the professional profile of these people in charge of the digital political communication functions, and in particular on Twitter: everything ranging from knowing their provenance, type of political involvement with the organization (hired, volunteer without pay, etc.), as well as what the professional profiles of the people who led this personnel were and their communication activities online.

A characteristic trait of all political organizations is the proliferation of volunteers, coordinated by a centralized, professionalized campaign team. The organizational characteristics of these volunteer networks, as well as their professional profile and tasks show small differences in the parties observed. In all the cases, these volunteer teams work in coordination with a stable communication and digital organization department of their own that is subordinated, depending on the case, either to the communication or press cabinet or secretariat (PP, PSOE, Ciudadanos, IU or UPyD), or else to the social networks team (Podemos). Their number is variable as is their territorial distribution depending on the party. Likewise, their professional profile varies greatly, in general, in all the political organizations. This diversity can also be found between the profiles of the coordinating team of each party, though it is true that in the latter case there is an abundance of journalists, computer programmers or graphic designers, more so than among the volunteer group, whose profile is more varied, where the involvement with the organization’s political project prevails.

In addition to the volunteers, it is possible to observe a versatile profile in the management of the Network campaign, in general in all the parties, for example, in Izquierda Unida’s group La Cueva, the profiles of the communicators managing digital communications, and therefore, twitter, was described like this: “There are some journalists, computer programmers, graphic designers, audiovisual technicians…” (Sic., IU interviewee), a team coordinated by a Communication expert.

As to the importance of digital communication on the Internet to the Spanish political parties, most of them claim that it is important, except for the case of Izquierda Unida who claim that it is essential. Even though the objectives that each party sets with their team for the digital campaign are different, according to the global results of the interviews, although in general terms the organizations interviewed point out that communication on social networks is successful and essential to them when they manage to attain repercussion on traditional media, especially on television.

In this sense, it is noteworthy that Twitter is presented as an important tool in the design of the strategy to most political parties, especially in the case of Podemos, even though it is not considered as a priority tool to any of these organizations that combine in their content strategies, planning and prevision of messages and issues with spontaneous contents.

Messages, viralization and repercussion of party strategy on Twitter

In total, of the 2.913 tweets that were posted from December 4th to December 23rd, 2015, 128 obtained more than 1.000 retweets, 41 of them surpassed 2.000, 13 had more than 4.000, four 8.000 and just two of them, posted precisely by the Partido Popular candidate , Mariano Rajoy, surpassed 20.000.

Together with them, the top 10 are made up of another 8 messages that do not surpass the 10.000 retweet barrier: there is a great difference between the most viral postings and those that followed them in the ranking. Of these, all come from the government presidency candidates, except for the seventh and ninth cases on the list, that belong to the Podemos corporate account. In terms of political parties, Partido Popular, Izquierda Unida and Podemos occupy 3 spaces in the ranking. The rest belongs to Ciudadanos, while Partido Socialista and Unión, Progreso y Democracia do not have any representation in this sense.

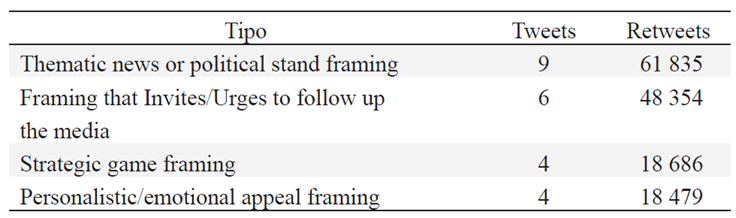

Generally, it is the political parties who have the most presence in the sample, with 88 of the 128 messages that make it up, of which 28 belong to Pablo Iglesias, 21 to Mariano Rajoy, 21 to Albert Rivera, 15 to Alberto Garzón, and the rest to Pedro Sánchez (2) and Andrés Herzog (1). The candidates that do not appear in this ranking, therefore, in general have a smaller number of tweets significantly viralized by Internet users. Regarding the organizations, 40 of the messages were posted by them, 17 belong to Izquierda Unida, 12 to the Partido Popular, 9 to Podemos, 1 to Partido Socialista and Ciudadanos. Unión, Progreso y Democracia does not obtain any postings in this case, and it ranks as the party with the smallest number of contents that have been highly retweeted. If all the organizations are taken into consideration, without breaking them down in terms of authorship, Podemos ranks first, with 37 tweets posted. It is followed by Partido Popular (33), Izquierda Unida (32), Ciudadanos (22) and finally Partido Socialista (3) and Unión, Progreso y Democracia (1) (Table 1).

As to the general topic of the messages, as it can be observed in the following Table 2, it is news events tweets and those directly related with a media follow-up that obtain total frequencies that are significantly greater than the rest of the framings (61.835 and 48.354, respectively). The framings of strategic game and personalistic/emotional appeal obtain practically the same number of viral retweets: 18.686 and 18.479, respectively. The logistic-mobilizing and pedagogic or didactic framings do not obtain high popularity rates among the followers of political organizations. The following lines concentrate the typology of each specific tweet in the parties, which have been ordered with respect to the number messages that were highly retweeted: Podemos, Partido Popular, Izquierda Unida, Ciudadanos, Partido Socialista and Unión, Progreso y Democracia.

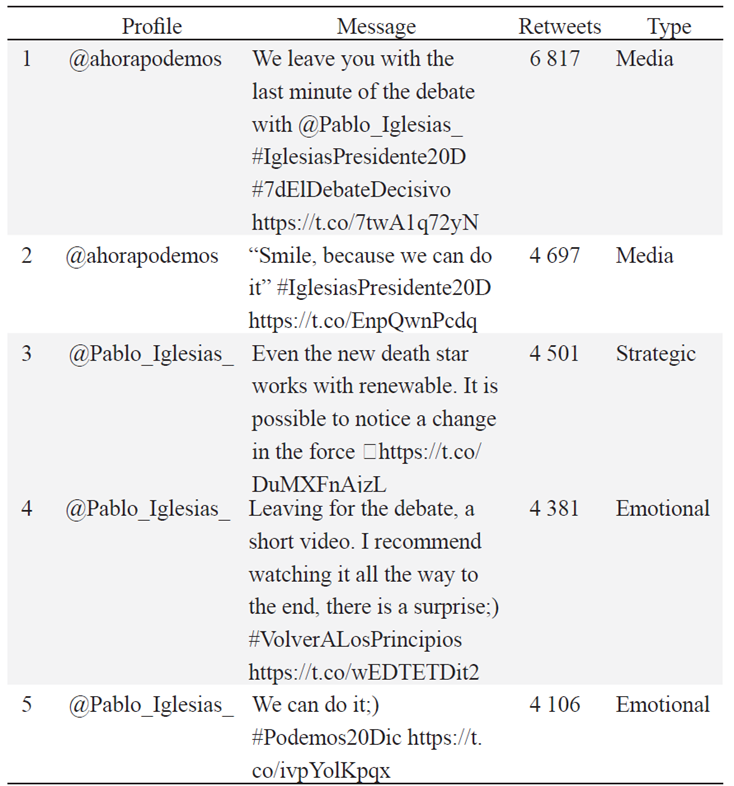

Podemos and their candidate to the government presidency with 37 messages, rounds up a total of 82.885 retweets, of which 60 526 belong to Pablo Iglesias and the remaining 22.359, to his political organization. However, the first two most viral tweets on the part of the party belong to @ahorapodemos, though the following three belong to the leader of the organization (Table 3).

The first two messages coincide in including the hashtag #IglesiasPresidente20D and approach a specific media event, the December 7 TV debate in which the four nationwide political organizations participated and according to public opinion estimations they would have parliamentary representation: Partido Popular -whose absence was covered by the government vice-president, Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría-, Partido Socialista, Podemos and Ciudadanos. The program’s format included a last minute for each of the candidates to make their request to vote -the presenters called it “the golden minute”-. The first of the tweets includes Pablo Iglesias’ monologue and the second one is an image of the moment with the last statement in the speech: “Smile, because we can do it”.

The fourth most retweeted message also comes from Podemos on that day, this time it was written by Pablo Iglesias. Although it refers to his appearance on television, the message fits a rather emotional frame, because it includes a promotional video entitled Volver a los principios (Going back to the beginning), in the form of storytelling, it criticizes a conservative drift in the PSOE in respect of its foundational ideology -inaugurated by Pablo Iglesias, that is useful in play of words- and it appeals to 15M movement’s political mobilization in Spain.

However, in the third message, Pablo Iglesias makes a cinephile’s reference: he attaches a Star Wars poster to act metaphorically as a winning force in the dynamics of the election campaign. Finally, the last message in this ranking includes also a visual element, but in this case it is one of personalistic appeal, because it is a photograph of himself voting on December 20 th, 2015. This way, the tweets that obtained the most popularity in the purple formation were related in all the cases with Pablo Iglesias, whether because he was the author of the message, because he stars in it or, in the case of Election Day, for both reasons.

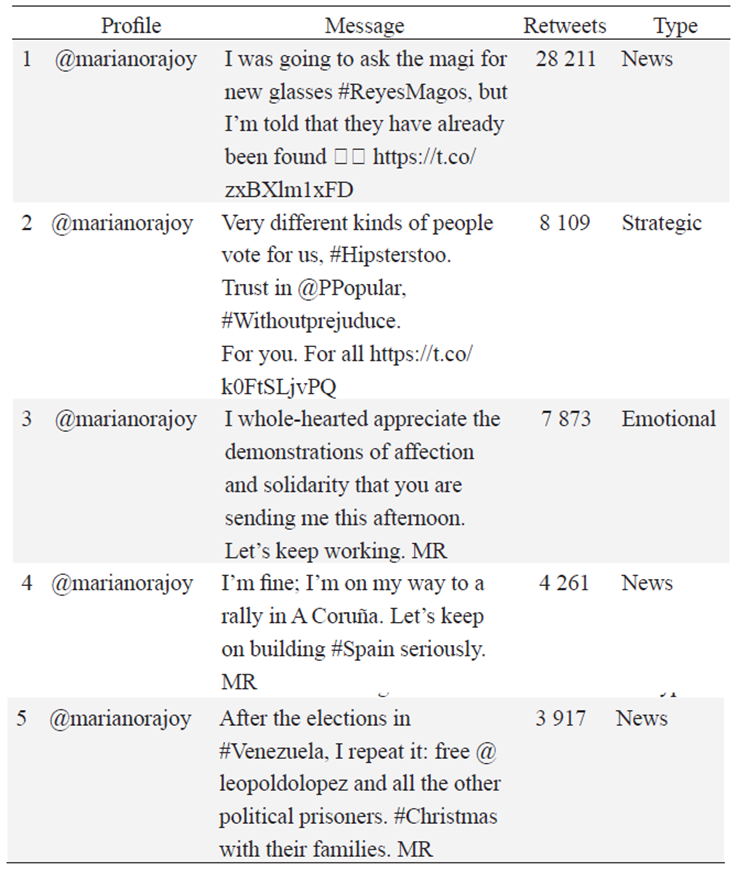

The political organization that won in 2015, and therefore revalidated their term of office in their previous legislature, received 94.484 retweets, 76.606 by Mariano Rajoy and 17.878 from Partido Popular. In addition, the five most viral messages belong to his profile, though only the first two are written by his team and not by him -when he does, he includes his initials “MR”- (Table 4).

Three of the messages that caused the most activity on Twitter deal with the same event: the attack on the President of the government during an electoral promenade in Pontevedra by a young minor on December 16th. The fourth tweet thus intends to provide information about his physical condition while he announces his next activity in the campaign. The third one, also authored by him, also has a more emotional tone, since he thanks the messages of support he received after the incident. The first message, though, is posted two days later and it is not signed by him, but it became the most viral message throughout the election campaign: humorously, he plays down the incident adding a photomontage wearing dark glasses in space, showing the place where they were left after the coup.

After the second message he also seeks the electorate’s sympathies, although this time with a strategic end, because it alludes to one of his campaign spots. Hipsters, too, referring to a subculture that is popular among young people to convey a public opinion detail: the Partido Popular is the formation that receives the most votes in Spain. The last message included among those that generated the most retweets in the organization is not directly related with the content of the election campaign in Spain, but with the country’s foreign policy: Rajoy provides information about the elections in Venezuela and he shows his support for opposition leader Leopoldo López and the rest of the political prisoners. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that this political stand in the national context acquires the meaning of a critique to Podemos, due to the political consultancy work that some of its leaders carried out in the South American country’s government. In sum, Mariano Rajoy’s account showed a substantive capacity for viralization during the 2015 campaign, which is linked to a large extent with a specific informative event. His team’s work to approach it from an ironic statement positioned it as the profile with the most popular message among all those analyzed.

On the other hand, the Izquierda Unida political organization, which attended the elections as Unidad Popular, obtained 90.596 retweets, 30.029 by the organization and 60.567 to Alberto Garzón, who in addition occupies the first four tweets of the party’s ranking (Table 5).

The December 7 debate, also known as the decisive debate, turned out to be the issue that went the most viral for the organization -3 of the tweets included the label #7DElDebateDecisivo- in spite of the fact that they did not take part in it. It was precisely this vindication that Internet users endorsed to a large extent, over 3.000 in the case of Izquierda Unida’s tweet that included the hashtag to that effect #FaltaGarzón (Garzón is not there), along with an image clipped from the politician’s profile. Alberto Garzón also alluded to the difficulties his organization had to develop their campaign strategy on television when they criticize that democracy is on “a diet”. An ironic tweet that became the most retweeted for the organization and the second most retweeted in the entire election campaign. Izquierda Unida’s of also appeals to humor in the second message in the ranking, related with another debate in the campaign, this time Cara a Cara (Face to Face). By alluding to two 19th-Century politicians, he describes the participants in the debate -Mariano Rajoy and Pedro Sánchez- as representatives of old-fashioned politics.

Once again, in the case of El debate decisivo, Alberto Garzón addresses a real-world issue, the price of college registrations in Spain, to propose to provide it for free, like in other European countries. Finally, the fourth message was posted on December 20th, on Election Day, and it uses a war metaphor -“we shall continue fighting”- while he thanks the people for participating in the elections. Izquierda Unida was the force with the smallest number of seats among the parties that attained representation in the Spanish Parliament. Despite this, they managed to have highly viral messages, above all those referring to the TV debates in which the party was not able to participate, but they have a relevant position in the electronic debate.

On the other hand, Ciudadanos as well as Podemos, obtained representation in Parliament for the first time in December, 2015, it had 42 726 retweets, almost all of them belonging to Albert Rivera, 41 015, while a small number corresponds to the party, 1 711. The candidate’s prominence is also explicit in the ranking of the organization’s most popular tweets, where he occupies all the positions (Table 6).

The two messages heading the list are dated December 16th, 2015 and they refer to the attack against Mariano Rajoy: the second informs about Albert Rivera’s activity that day, when he contacted the President, while the former criticizes the stands that justify violence against Rajoy. Therefore they both fall within the frame of news. The third and fourth tweet also makes reference to current reports, specifically to statements by other political organizations that clashed with Ciudadanos. On the one hand, it admonishes socialist politician Carme Chacón for having used some fake tweets by Albert Rivera himself. On the other hand, more ironically, it alludes to statements by a Partido Popular councilman who insulted his party comrade Cristina Villacís, and he adds a picture of himself eating with the hashtag #Yotambiénestoyfondona (I’m also fat).

Finally, the organization’s fifth most retweeted message uses the framing of strategic game to aim at the majority parties’ post-election strategies, PP and PSOE, and to ask them to abstain if they are in power. This request is used to explain Ciudadanos' own tactic, by which they will allow the winning party to govern -as it eventually happened in 2016-. In sum, the messages that have worked better for Ciudadanos in terms of viralization were those proposed by the candidate. In addition, they mostly alluded to other parties or candidates as well as to specific events that had special relevance for the media, even when they were not directly connected with the election campaign, as in the case of hashtag #Yotambiénestoyfondona.

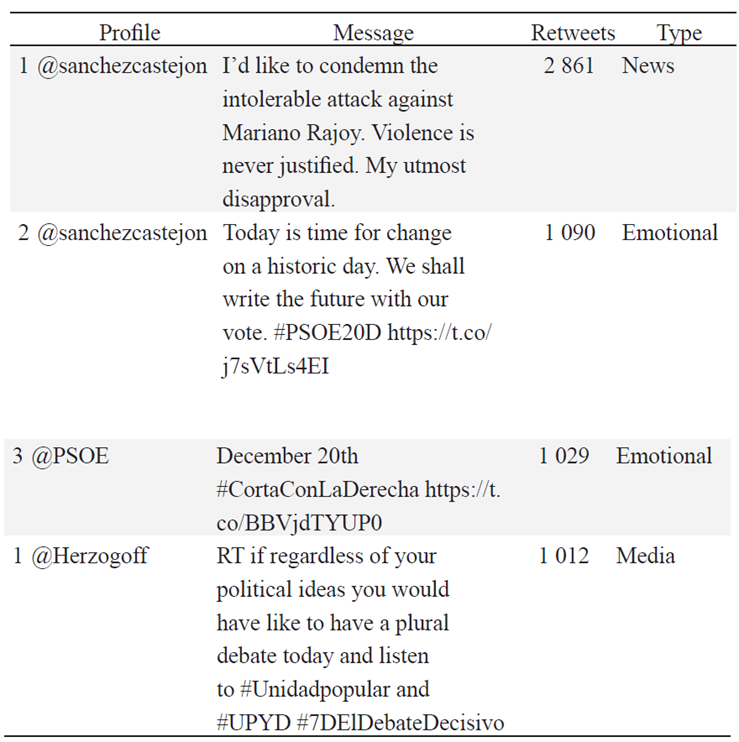

However, Partido Socialista and Unión Progreso y Democracia are the parties with the least capacity to have their messages become viral. In the former case, they get 4.980 retweets, 3.951 on the candidate’s account and 1.029 on the organization’s, while in the UPyD the number drops to 1.012, all of them in the case of Andrés Herzog (Table 7).

Pedro Sánchez is the person who writes the message with the largest number of tweets in Partido Socialista, he refers once more to the attack against Mariano Rajoy on December 16th. The following post has a rather personalistic approach, since it shows a photo of Pedro Sánchez voting on December 20th, an analogy with the one mentioned above posted by Pablo Iglesias -in this case with 3.016 retweets less-. The last of the tweets, written by the PSOE profile, includes an electoral spot Corta con la derecha (Cut your ties with the right), so it can be interpreted as an appeal for the electorate to take a stand against the rightist parties -be it the Partido Popular or Ciudadanos, according to the video- and to show their sympathies for the socialists. Finally, in the only posting made by UPyD, written by Andrés Herzog, he vindicates not only his appearance on El debate decisivo, but also that of Unidad Popular (Izquierda Unida).

Therefore, on the content level, these organizations repeat the formulas indicated in the rest of the parties analyzed, though with worse results in terms of viral tweets. Although the latter party disappeared from the chamber in December, 2015, the PSOE continues as the second most powerful political force, so their lack of retweets is not indicative of their subsequent number of voters.

Conclusions

The data confirm the importance of coordinating the digital with the traditional campaign on digital media in the design, planning and repercussion of the campaigns. That is evident not only in the makeup of the work teams and the organization of the digital campaign departments, which work either in coordination with or integrated in the communication departments, but also that the most viral Twitter messages are precisely the media messages, that is, those that have been first broadcast on television or those that, taking advantage of a TV event (such as the electoral debate) become viral on Twitter.

This effect is crystal-clear in the case of the messages that include hashtags about media events that are announced on television, and therefore they are written while the show is being aired, such as in the case of Alberto Garzón’s tweet, posted on December 7th, at 11:17 pm -the show started at 10 pm- with the label #7dElDebateDecisivo. In the case of the attack against Mariano a Rajoy, it is also possible to confirm that the Twitter messages are subsequent to the earliest information about the event: if El País headlined “Attack on Mariano Rajoy in Pontevedra” on December 17th at 10:51 pm,3 Mariano Rajoy posted his most viral message the following day at 11:07 am.

This way, it is confirmed that, indeed, Spanish political parties structure their campaigns following the traditional model or, at least, planning their strategy for message diffusion in coordination with the traditional media, which is reflected in a greater upturn of retweets and therefore of most followed messages.

Side by side, it is possible to observe that the political parties that manage to plan their messages considering the characteristics inherent to the Internet and have the collaboration of campaign volunteers in their diffusion, are the ones that achieve a larger number of viral messages. For example: Podemos, in terms of the number of highly retweeted messages (37) and Izquierda Unida, receiving 90.596. On the contrary, UPyD is the organization with the least messages and retweets, followed by PSOE. Nevertheless, it is also observed that the activity in this social network, therefore, does not have a clear correlation with the election results: Podemos turned out to be the third force at the polls, while PSOE was the second one, IU obtained two representatives and UPyD, none.

The candidates are the most retweeted profiles, both in terms of number of clicks received and in terms of highly viral messages: they occupy more positions in the rankings and have the only tweets that surpass 20.000 retweets, in the case of Mariano Rajoy and Alberto Garzón. Both postings coincide in that they use humor to approach two of the most popular issues during the campaign. Both the attack against the President and the December 7 debate became two current events that attracted special attention in the micro-blogging network and in all the parties their reactions to them were part of the most viral tweets. On occasion, reference is made to election spots and stands against other political organizations

REFERENCES

Barron, R. (2008). Master of the Internet: How Barack Obama harnessed new tools and old lessons to connect, communicate and campaign his way to the White House. Recuperado de http://web.cs.swarthmore.edu/~turnbull/cs91/f09/paper/barron08.pdf [ Links ]

Borondo, J., Morales, A. J., Losada, J. C. & Benito, R. M. (2012). Characterizing and modeling an electoral campaign in the context of Twitter: 2011 Spanish Presidential election as a case study. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 22 (2), 1-5. [ Links ]

Casero-Ripollés, A., Feenstra, R. A. & Tormey, S. (2016). Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign. The case of Podemos and the Two-Way Street mediatization of politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21 (3), 378-397. DOI: 10.1177/1940161216645340 [ Links ]

Congosto, M., Fernández, M. & Moro Egido, E. (2011). Twitter y política: información, opinión y, ¿predicción? Cuadernos de Comunicación Evoca, 4, 11-16. [ Links ]

Dader, J. L. (2016). El nuevo escenario de las campañas digitales y su reflejo en unas elecciones regionales: el caso de Castilla y León, 2015. En J. L. Dader & E. Campos-Domínguez (Coords.), La cibercampaña en Castilla y León. Elecciones autonómicas, 2015 (pp. 11-20). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid. [ Links ]

Delany, C. (2009). Learning from Obama. Lessons for online communicators in 2009 and beyond. Recuperado de http://www.epolitics.com/learning-from-obama.pdf [ Links ]

Graham, T., Broersma, M., Hazelhoff, K. & Van't Haar, G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters: The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK General Election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 16 (5), 692-716. [ Links ]

Hendricks, J. A. & Denton, R. (2010). Political campaigns and communicating with the electorate in the Twenty-First Century. En J. A. Hendricks & R. Denton (Eds.), Communicator-in-chief: How Barack Obama used new media technology to win the White House (pp. 1-18). Lanham: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Iglesias, D. (2012). USA 2012: La nueva frontera de las campañas digitales. Campaign & Elections, 28, 32-35. [ Links ]

Kreiss, D. (2015). Digital campaigning. En D. Freelon & S. Coleman (Eds.), Handbook of digital politics (pp. 118-135). Nueva York: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

López-García, G. (2016). ‘New’ vs. ‘old’ leaderships: The campaign of Spanish general elections 2015 on Twitter. Communication & Society, 29 (3), 149-168. [ Links ]

Mattelart, A. & Vitalis, A. (2015). De Orwell al cibercontrol. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Mazzoleni, G. (2001). La revolución simbólica de Internet. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación. CIC, 6, 33-38. [ Links ]

McChesney, R. W. (2015). Desconexión digital. Madrid: El Viejo Topo. [ Links ]

Moceri, A. (2012). Elección 2012 de EE.UU. ¡Son los datos, estúpido! El Molinillo Revista de la Asociación de Comunicación Política. ACOP, 48, 8-11. [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Dader, J., Téllez, N. & Salazar, A. (2016). ¿Están los políticos políticamente comprometidos? Análisis del compromiso político 2.0 desarrollado por los candidatos a través de Facebook. Cuadernos.info, 0 (39), 135-150. [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle. Political communications in postindustrial societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Redondo, M. & Calvo, D. (2016). Las estrategias de comunicación online. Visión y planificación de los partidos políticos. En J. L. Dader & E. Campos-Domínguez (Coords.), La cibercampaña en Castilla y León. Elecciones autonómicas, 2015 (pp. 53-66). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid . [ Links ]

Sampedro, V. (2011). Cibercampaña. Cauces y diques para la participación. Las elecciones generales de 2008 y su proyección tecnopolítica. Madrid: Editorial Complutense. [ Links ]

Sánchez Duarte, J. M. & Magallón, R. (2016). Estrategias de organización y acción política digital. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación, 3 (5), 9-16. [ Links ]

Schweitzer, E. J. (2008). Innovation or normalization in e-campaigning? A longitudinal content and structural analysis of German party websites in the 2002 and 2005 national elections. European Journal of Communication, 23 (4), 449-470. [ Links ]

Schweitzer, E. J. (2011). Normalization 2.0: A longitudinal analysis of German online campaigns in the national elections 2002-9. European Journal of Communication, 26 (4), 310-327. [ Links ]

Smith, M. (2010). Political campaigns in the Twenty-First Century: Implications of new media technology. En J. E. Hendricks & R. Denton (Eds.), Communicator-in-chief: How Barack Obama used new media technology to win the White House (pp. 139-155). Lanham: Lexington Books . [ Links ]

Solop, F. I. (2010). RT @BarackObama we just made history. En J. E. Hendricks, J. Allen & R. Denton (Eds.), Communicator-in-chief: How Barack Obama used new media technology to win the White House (pp.465-491). Lanham: Lexington Books . [ Links ]

Strandberg, K. (2008). Online electoral competition in different settings. A comparative meta-analysis of the research on party websites and online electoral competition. Party Politics, 14 (2), 223-244. [ Links ]

Vaccari, C. (2010). Technology is a commodity: the Internet in the 2008 United States presidential election. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7, 318-339. [ Links ]

Ward, S., Gibson, R. & Lusoli, W. (2008). The United Kingdom: Parties and the 2005 virtual campaign-not quite normal? En S. Ward, D. Owen, R. Davis & D. Taras (Eds.), Making a difference. A comparative view of the role on the Internet in election politics. Lanham: Lexington Books [ Links ]

1This investigation is framed within the projects of the national I+D+i plan “Las estrategias de campaña online de los partidos políticos españoles: 2015-2016” (reference CSO2013-44446-R) and “Estrategias, agendas y discursos en las cibercampañas electorales: medios de comunicación y ciudadanos” (reference CSO2016-77331-C2-1-R).

3El País (2015). Agresión a Mariano Rajoy en Pontevedra. Available at: http://www-elpais.com/elpais/2015/12/16/videos/1450292418_691266.html. Last access: 02//02/2017.

Received: December 23, 2016; Accepted: January 24, 2017

texto em

texto em