Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicación y sociedad

versão impressa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc no.29 Guadalajara Mai./Ago. 2017

Articles

Persuasive strategies in electoral propaganda. Analysis of the television broadcasts transmitted during Jalisco’s Electoral Campaign in 2015

1Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

This research analyzes the persuasive strategies used by the electoral broadcasts of the nine political parties that contended for Guadalajara’s mayor’s office in 2015, as well as those from the independent delegate candidate, Pedro Kumamoto. For this endeavor, Arantxa Capdevila’s methodological proposal and some contributions from film theory and film aesthetics were recovered, since the article discusses audiovisual products intimately linked to this cinematic tradition.

Keywords: Political communication; political propaganda; tv spots; rhetoric; aesthetics

Este texto analiza las estrategias persuasivas que utilizaron los spots electorales de los nueve partidos políticos que contendieron por la alcaldía de Guadalajara, así como los del candidato independiente a diputado Pedro Kumamoto en 2015. Para ello se recuperó la propuesta metodológica de Arantxa Capdevila, así como algunos aportes de la teoría y la estética cinematográfica, puesto que se trata de productos audiovisuales íntimamente ligados a esta tradición.

Palabras Clave: Comunicación política; propaganda política; spot televisivo; retórica; estética

Introduction

Electoral propaganda articulates in the same terms as advertising propaganda, its aim is to make an impact on the audience to get their vote in a given campaign. That is, “in essence political propaganda is no different from advertising, the latter concept presupposes to make something known, advertise it, a way of propagating it so as to stimulate demand of goods and services” (Corona, 2011, p. 326). Electoral propaganda aims at making a given candidate known, or even a party that has been recently created seeking to position itself. It does not intend to just inform using data or proposals, but rather to convince through emotions. According to Corona (2011):

…targeting the masses, political propaganda intends to exert its influence with emotive effects and not through reasons. Exaggerating the candidates’ qualities and concealing their defects, just like it would happen with products. Political propaganda, made by skilled specialists and foreign advisors, intends to interpret and answer surveys, study different aspects of electoral behavior, to offer the people what they want to hear (p. 326).

To this end, they make use of a series of persuasion strategies, some of which are more effective than others, since they allow positioning the product better. These strategies appear in the parts of the discourse and the way they are presented. Studying them allows not only understanding how persuasive messages articulate, but also explaining the relation between these propaganda communicative processes and the results at the polls.

In Mexico, politics and the party system are going through a period of distrust, which is why electoral propaganda has to be more solid when it tries to convince and ask for the citizens’ vote. Along with this, the recent electoral reforms have caused a large part of the communicative exchange between political parties and citizenry to occur through the media. This is a big deal, since as Reardon claims “all the forms of communication exert an influence on who we are and what we want to be, they even shape it up. But the forms of communication that invade us the most are the mass media” (1983, p. 205).

The medium with the most impact on the electorate continues to be television, and their star product to attain this rapprochement between candidates and citizens: the spot. This is due to, firstly, the electoral reforms and the change in the rules for this type of advertising on radio and television which condensed electoral advertising in the political spot in Mexico (Benassini, 2016; Hernández 2016), and secondly, to the impact these brief products leave on the audience (Orozco, 1997). According to Rodríguez (2003):

Television has been and still is stronger and stronger, its influence is decisive in different spheres. It is also influential in the relation established between the political candidates and those who elect them. However, there is an evident aspect: television helps the democratic system by bringing the leaders closer to the citizens. Without the cameras, this contact would not better or worse. In most cases it would simply not exist (p. 46).

It should also be considered that this phenomenon is changing and that the use of social networks is taking over the political debate ever more strongly. However, this transition has not yet completely materialized in Mexico due to the fact that the access gaps continue to leave out the majority of the population. This fact reinforces the need to analyze the way in which television has taken part of the campaigns, through the broadcast of electoral spots. In the near future, this would allow comparing these strategies with the ones suggested by the social networks, which still have not replaced, but rather complement, those of television.

Therefore, the objective of this text is to analyze the persuasive strategies used in the 50 electoral spots of nine parties and one independent candidate, which were transmitted on television during the campaign for the mayor’s office in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco state, in the context of the State Elections in 2015. We do this with the aim of acknowledging what arguments and discourses are presented to convince the citizen, how they do it through the use of images and sounds.

In theoretical-methodological terms, we have recovered the studies by Capdevila (2004) who, along with Pericot has worked with respect to political communication and the analysis of electoral propaganda in the last few years. Capdevila uses a rhetoric-argumentative model, built on the basic principles of Aristotelian rhetoric (Albaladejo, 1989), Perelman’s theory of argumentation (1989) and the incorporation of Goodman’s concept of “possible worlds” (1990), which allows speaking about the impact pretensions on a given type of audience. To strengthen the properly audiovisual categories of analysis, Capdevila’s model is complemented with the image taxonomy proposed by Deleuze in The movement-image: cinema 1(1984), as well as Bordwell and Thompson’s work on cinema language (1995)2. Persuasive strategies in TV spots can be discursive and narrative, but they are above all visual and sound strategies, because it is images and sounds -in addition to the way they are presented - that provoke these emotions and sensations. Hence the importance of arguing from the cinema tradition, the point of departure for audiovisual studies, even the contemporary ones (Benet, 2015).

Theoretical framework

Political communication according to Ochoa (2000) is made up of six areas of interest: public opinion, the analysis of the content of messages, political-social behavior, the leadership of power groups, the effects of political communication and political propaganda. This study is placed in the latter, and more specifically, within electoral propaganda. This is the one generated during the campaigns prior to the elections, one of the periods with the greatest propaganda production, the one with the greatest social impact:

In democratic systems, communicative processes aimed at persuading are essential because they are on the basis of the relations between citizens and politicians, but their importance increases during the electoral campaign when all the political parties deploy their persuasive strategies so as to obtain the maximum possible number of adhesions. This fact makes these periods, which are much delimited in time, particularly interesting for the analysis of persuasive strategies. In societies like the current one, persuasive processes are carried out mainly through the mass media, among which television stands out -the medium that is most followed by the voters to get information about politics- (Capdevila, 2005, p. 239).

Capdevila’s rhetoric-argumentative model (2004) was developed to analyze electoral propaganda, specifically TV spots produced by political parties during specific electoral campaigns. Departing from the fact that rhetoric is the science or rather the art of persuasion, his model recovers Perelman’s contributions (1989) developed in his book Treatise on argumentation: The new rhetoric, in which he updates the Aristotelian postulates and constructs a model that is divided into three fundamental parts: general agreements, procedures of argumentation and the interaction of arguments.

The general agreements refer to previous knowledge about the audience which will facilitate persuasion; the procedures are responsible for the audience to accept new ideas, using logical, convincing arguments. Interaction of arguments refers to that which occurs between the discourse and other contexts, according to Capdevila (2005), the part that has been developed the least in Perelman’s model.

When constructing his model of analysis, Capdevila recognizes that, in the general agreements proposed by Perelman, there are some suppositions of what the model public is like (Eco, 1992). In this first stage he also distinguishes the need to create a series of reference frameworks or possible worlds (Goodman, 1990), that allow previous knowledge of the audience that is being persuaded, so that the most adequate discourse is selected.

The model consists in recognizing the rhetorical operations involved in the discourse to understand how they operate within it and thus analyze what the main arguments explained by the spot are. At the same time, the model allows recognizing how these arguments are organized to influence the spectator and what figures are used to embellish the discourse and move the audience.

As mentioned above, electoral spots inform but they mainly move, since the characteristics of their format privilege the transmission of affectivity above that of rational argumentation (Dallorso & Seghezzo, 2015). In addition, the spot uses the same mechanisms as commercial publicity to get closer to the audience, although unlike electoral propaganda, it is much more regulated both in terms of the frequency with which their messages are repeated (Hernández, 2016) and in terms of their content.

In addition to the Capdevila’s work, a couple of theoretical contributions were taken into account to complement the study from the cinema tradition, and they allow reinforcing reflection on audiovisual persuasion proper. The first is Deleuze’s image classification work (1984) contained in his book The movement-image: cinema 1, a complex text where it is possible to distinguish a semiotic part -dedicated to the debate of signs and properly to answer to Pierce-, a peculiar story of cinema -that recovers specific artists and works - and the taxonomy of images that makes up classical cinema. Along this line, Deleuze argues that the latter is based on the notion of cause and effect, in which the entire filming artifact is hidden to give more importance to the story told. This work divides images as summarized below:

In movement-image we can find the three types of images: image-perception, image-action and image-affection. Images-perception are the bodies, which are presented as long shots. The editing with which they are associated is that of sets, like the ones used by Dziga Vertov in his films. Images-action are defined as acts; they are built from medium shots and they are articulated through the editing process of action, as it happens in Griffith’s films. Images-affection are adjectives; close-ups, usually of faces. The editing that characterizes them is also called affection editing, which can be found, for example, in Carl T. Dreyer’s films (Alcalá, 2010).

This division allows recognizing a function in cinema forms, clarifying that the use of certain types of shots or editing conditions effectiveness of the message and its emotiveness, which is why it is pertinent to know it for this analysis.

The second contribution considered is Bordwell and Thompson’s work (1995), which explains the parts into which cinema language is divided and that is why it allows distinguishing the photographic, sound, production, art direction and editing elements into which the film is divided. Spots should be understood as a brief film in which all of these elements contribute in its articulation. That is why it is necessary to have a reference framework like this to name its parts following the cinema tradition.

Analysis model

In order to examine each of the 50 spots, an analysis fiche was prepared taking into account Capdevila’s contributions (2004) and adding some other categories that originated form Deleuze’s (1984) and Bordwell and Thompson’s (1995) contributions on esthetics and cinema language. The categories or indicators were divided into three great sections that are explained below.

Enunciator: Who is talking? A narrator, the candidate himself, some political figure from his party, the electorate, or several of them. A lot depends on whose voice addresses the audience, since the legitimacy and trust with which the message is received comes from this fact. In Capdevila’s words: “the enunciator is the discursive role played by the orator, who in the case of audiovisual communication delegates the explanation of the message -which is cognitive and perceptive- into several enunciators: allied, neutral and opposing enunciators” (2005, p. 245).

Statement: what does the spot tell us? Is it a discourse to know the candidate’s capacities, to underscore some characteristic in particular or to present a concrete proposal? Other discourses can also be found, such as those discrediting others or presenting the party’s stand. Other categories derive from this one, which are formal in character: what audiovisual genre does it belong to? What other tone is it presented with? Are their images mainly open spaces, a series of actions or just close-ups?

Addressee: Who is it addressed to? Each spot has a model reader (Eco, 1992) whose characteristics are imagined from its creation, and identifying them allows assessing whether the persuasion strategies were the correct ones. “Addressee is the discursive role played by the audience who is the discursive subject who receives, watches or listens to the information. And it can be direct or indirect” (Capdevila, 2005, p. 245), that is why it is not very evident in some cases and it will be necessary to read between the lines to detect it.

Lastly, the category of “values” was included, since the electoral spot, rather than an information instrument, is a product to impact and advertise. Their persuasion strategies are not only based on solid arguments but also on transmitting values. For example, an automobile commercial, rather than describing its mechanical characteristics, will claim that if you own this car, you will have power, freedom and class. Likewise, an electoral spot seeks to buy, with the candidate -through the vote- a specific life style or other, in which the important elements are the family, security, among others:

Values are generalized, agreed-upon opinions. There are two types: general ones, which are abstract and based on rules accepted by everyone under any circumstances -for example: justice, liberty, truth-. These are very useful persuasion instruments since they can be defined in many different ways according to the ideology of those who defend them. On the other hand, there are particular values that are attributed to a particular being or group. They have a unique, genuine character that allows them to disavow the others -for example, virtue, fidelity, friendship- (Capdevila, 2005, p. 240).

These categories were applied to each of the spots to later make a comparison between the parties and the independent candidate. These were the results (see Table 1):

Results

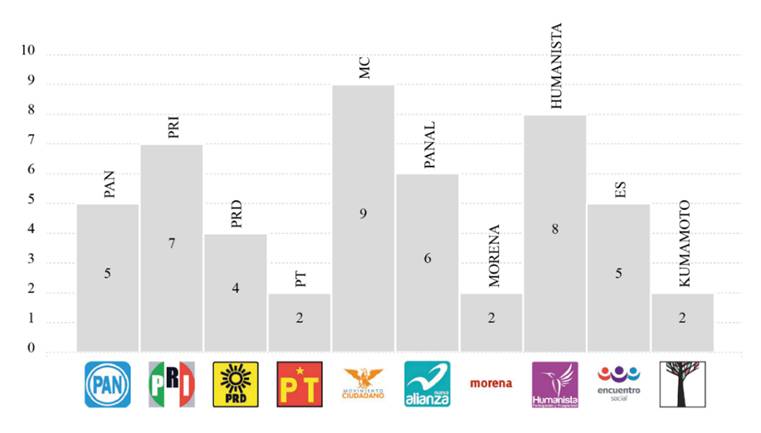

The corpus of spots analyze included a total of 50 audiovisual promotional materials produced by the nine political parties that contended for the Municipal Presidency of Jalisco in June, 2015,3 as well as those aired by the candidate to the State Congress by district 10 of Zapopan, Pedro Kumamoto. The latter was chosen because it was considered an exceptional case, since it was an independent candidacy, which in addition to receiving strong support on the part of the citizens since he registered as a candidate (Yáñez, 2016), it was the first time a candidate like this wins an election in the state of Jalisco. This is the total number of spots analyzed per party (Figure 1).

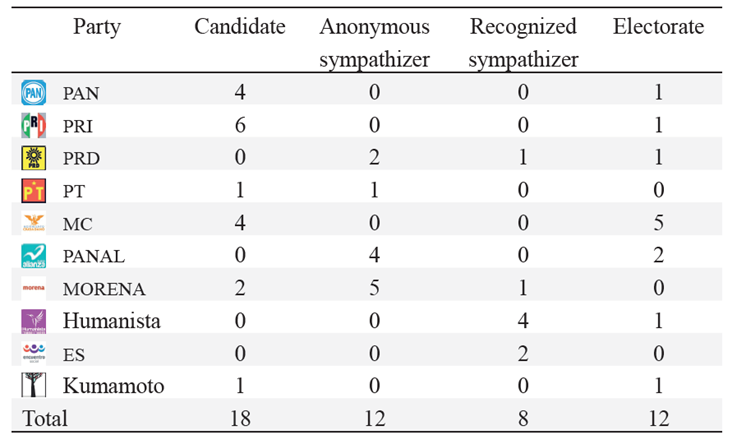

When identifying the category of enunciator in the 50 spots, it was possible to observe that the entirety of the corpus presents enunciators that favor the party, who were classified into 4 categories: the candidate, anonymous sympathizers, recognized sympathizers and several versions of the electorate. The first classification considers those spots in which the candidate appears talking with the electorate. The second refers to those in which the main voice is that of a sympathizer favoring the party that can be recognized neither as a voter nor as an explicit member of the party. The third includes interlocutors sympathizing with the party who were recognized by their celebrity status or their notoriety as members of the party. The last classification refers to the protagonists that perform some activity that identifies them as potential voters or as an equal to the addressee. For example: citizens voting at the polls or groups expressing their affinity for some party, without showing a badge that identifies them as members.

The addressee that appeared the most often was the candidate, on 18 occasions. Followed by the anonymous sympathizer and the electorate, on 12 occasions each. Recognized sympathizers appeared 8 times ( see Table 2).

The findings about the enunciator reveal several characteristics of the parties behind the spots. For example, those that chose to present recognized sympathizers did not show their candidates talking, or did not show them at all. Those who followed this tendency were small or recently-created parties, which could mean that their choice of a famous figure over their own candidate is indicative of the fact that they recognize that they had little chance of winning the elections. It can be inferred that the objective was to seek votes for the party so that it had the minimum number of votes necessary to ensure its existence as such, despite the fact that they anticipated that their candidate was not going to win the elections.

Another interesting tendency is that the party that most often gave voice to the electorate was MC, which used it as addressee in five of their nine spots -the other four are starred by their candidate-. This fact is important because this party eventually won the election. The tendency to show the electorate also gains relevance in the case of Kumamoto, another winner, who, although he launched only two TV spots, shows the electorate as the enunciator in one of them and the candidate in the other.

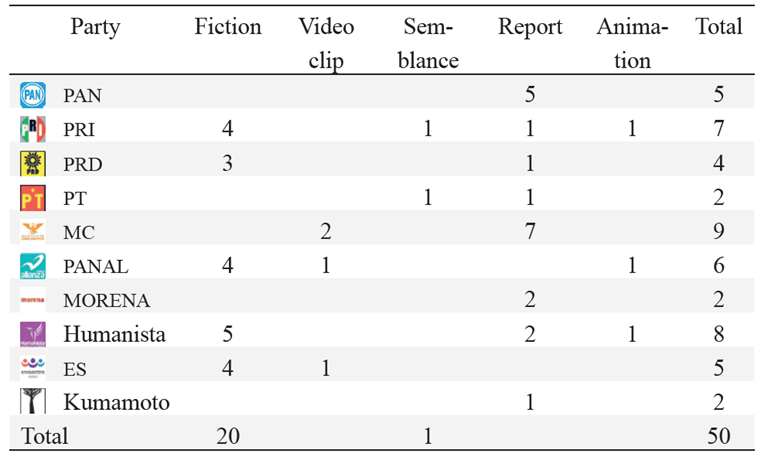

As to the genres, the 50 spots were classified into five: fiction, music video clip, semblance, report and animation. The two most often used were the report and fiction with 20 incidences each. It should be pointed out that the music video clip was only used four times but there is evidence that shows it is a genre that is gaining relevance. Even though it is not often used in political propaganda campaigns, the ease with which it appeals to emotions, its festive tone and its ability to be memorized, position it as a strong audiovisual persuasive strategy. Suffice it to say that the party that proved to be stronger in terms of results, MC, released two of them at the beginning of the campaign and as it advanced, two other smaller parties -PANAL and ES- chose to launch their own video clips. Both parties used esthetic tactics that distanced themselves from the ones prevailing in their previous spots, which is indicative of some sort of imitation of MC’s proposal: presenting different characters that are happy and mainly young. In turn, semblance and animation were the genres that appeared the least frequently, only three times each.

The tendency for the fiction and video clip genres indicates that there is an inclination to appeal to the emotions, since they are both very flexible and do not demand high degree of realism or verisimilitude. On the other hand, the popularity of the report essentially seeks the opposite. Since it is built more realistically, the report tends to resort to evidence and the “facts” to prove or argue that the candidates or the party are capable of yielding results. Nevertheless, though this genre has a rather documentary tendency, it is not devoid of dramatizations. For example, in a PRI spot about the family, the candidate is shown interacting affectionately with his wife and daughters, in addition, there appear emotive photographs of his youth, his family and his memories of the city. As a whole, the images evoke a yearning for a better time and they present the candidate in a warm, sensitive light, even though they manage it from real images. Another interesting case is that of a PT spot, which shows the female candidate interacting with other women, giving them affection and getting close to them, which is also a way to appeal to emotions from real images (see Table 3).

The party with the most variety of genres -fiction, semblance, report and animation- was PRI. It should be pointed out that this is one of the oldest parties and at the time of the elections it was in power at the three levels of government: local, state and national. The large investment of resources in the party spots is evident not only in the quality of their production, but also in their contents, since they approach a different issue in each of them: family, education, employment, security, economy and city remodeling, in addition, they produced a spot in which the citizens enunciate the candidate’s promises.

Regarding the tones of the spots, three were identified: the hopeful, the festive and the transition ones. The latter is understood as one of the spots that started tragically, but as they progressed and the candidate or party was introduced, they became optimistic. The transition tone is interesting as a persuasive strategy, since in order to argue better the benefit of voting for a certain party or candidate, it is important to first point out everything that is negative about the present panorama. This tone was detected in 16 instances, while the festive one appeared only in 4. The hopeful tone was the one detected the most often, 30 times ( see Table 4).

With respect to images, it was detected that images-action prevailed, since 34 of the spots were built mainly with medium shots and American shots. Images-affection come right after images-action, with 10 examples, and lastly images-perception, with 6. Within images-perception, it was detected that almost all were shot in exteriors, with day light and monuments or people doing activities that require physical movement. Only one of the parties -ES- concentrated their images-perception in a totally closed space. In the use of images-affection, two tendencies were identified: mainly showing faces -Kumamoto, PRD and MC− or else shots detailing objects that are specifically symbolic or parts of the body -PANAL-. In the case of the most frequent, images-action, three main uses were identified: to accompany the discourse of the actions that the candidate is performing -although at times they do not match-, to represent the electorate in their everyday life and to frame the characters as they speak with the spectator -see Figures 2, 3 and 4-.

Although the use and combination of the three types of images allowed identifying the parties’, the candidates’ and the citizens’ qualities in the spots, the soundtrack set the guidelines on which the images were interpreted. Thus, the music, the incidental sounds and the voices that made up the soundtrack of each spot allowed detecting who carried the weight of persuasion -whether it was the candidate, the party’s sympathizers or the citizens-.

In the case of the music video clips -MC, ES and PANAL- persuasion fell on the citizens who expressed their support to each party singing short, repetitive phrases with festive rhythms. In the remaining spots, the music set persuasive guidelines by increasing their impetus and solemnity, whether upon presenting the element of change offered or to mark the contrasts between the panorama created by the parties in power and the one offered by their contenders.

As to the voices, four types were detected. In some spots, the voice was that of the candidate -PRI, PAN, MC, PT, Kumamoto-, in others it was that of the sympathizers who were somewhat recognized -PRD, ES, MORENA-, or else it was the voice of anonymous sympathizers in voice over -PT, PANAL, HUMANISTA-. Lastly, the testimonial voice was that of anonymous sympathizers that addressed directly the addressees to persuade them from their experiences or alleged relations with the candidate. This resource was most often used by MC, three times. PRI, PAN and HUMANISTA also used it once each.

As to incidental sounds, it was detected that they were not used in persuasive terms, since they were only used to emphasize the storytelling of the spots.

Within the corpus no party was detected identifying their addressee explicitly. Those presented here were detected from visual elements, topics and key words that targeted certain citizen groups more than others. In addition, it is argued that the spots address their addressee with a persuasive logic by identification with what the spot shows. In 27 of the 50 spots, it was not possible to find enough elements corresponding to one addressee in particular, therefore, in these cases it is considered that the spots speak to the citizenry in general. The rest of the spots can be classified into seven sets according to the addressee they target: the young, trade workers, middle-aged adults, women, family parents, leftist militants and professionals.

The classification of young people was detected in five of the spots. Three of them corresponded to music video clips in which they were portrayed active in a festive attitude -MC, ES and PANAL-, while one of them showed them performing activities that are not stereotypical actions performed by the young, such as knocking on doors and collecting signatures for a candidate -Kumamoto-. This observation is interesting because it speaks of a specific type of young people that does not appear in other spots: those who are knowledgeable in politics and -by affinity with the candidate- with access to higher education.

Trade workers were given priority in five spots, and though several trades were shown, shopkeepers were a constant in the five -PAN, PRD, PT, MC and HUMANISTA-. Another classification that was found was that of middle-aged adults, which led to realizing that three of the spots were starred by a comedian -Héctor Suárez- who was especially popular during the 1970’s and 1980’s, therefore he would hardly have any influence on younger generations. On the other hand, three parties -PRD, PT y MC- gave prominence to women and to underscoring qualities that are stereotypically feminine in at least one spot by each. This is interesting because two of the parties had women candidates and it is noteworthy that they are presented from their gender identification.

In two spots -MORENA- it was found that the addressee was a leftist militant, since they spoke of contextual events that characterize the group, and in addition they were starred by a leftist figure -Andrés Manuel López Obrador- instead of the candidate. Another finding was that in two of the spots children play an essential role within the persuasive strategy -MC and PANAL-, therefore family parents were identified as addressees. Only on one occasion the electorate made up of professionals was shown, which relates with older addressees. Said spot was produced by the same party that focused on middle-aged adults –ES-.

The main tendency in the spots was to address the citizenry in general and not to name the addressees explicitly. This could be interpreted in two different ways: as a propensity by the parties to bet on what is certain and not let anyone out, or else as a way of avoiding being openly related with certain groups. The attempt to speak directly to the young rather than to the older electorate was also more evident, and even though it is possible to detect diversity among the working class, there is greater emphasis on shopkeepers than on other types of workers. In the case of the representation of women, it is noteworthy that the two female candidates sought to present themselves as having stereotypically feminine qualities, such as the tendency to emotiveness and vanity.

The values offered to the electorate in exchange for their vote were diverse: hope for change, empathy, honesty or righteousness, social commitment, gratitude -as the candidate’s testimony and guarantee-, respect for human rights, retribution to bad rulers, social visibility, collectivity and decent work. The value detected most often was change, on 28 occasions, followed by empathy with five and honesty and social commitment with four examples each. Gratitude appeared three times, while respect for human rights was offered twice. The rest of the values only appeared once: retribution, visibility, collectivity and decent work.

Although hope for change of the status quo underlies almost all the promises in the spots, the most interesting finding in this category is in those values that were presented the least often, for they corresponded to the qualities with which some of the parties seek to identify beyond the elections. In the case of honesty, it was detected that recently-created parties promised not to be like others that have already become corrupted. Respect for human rights and visibility of the minorities are values with which the leftist parties build their identity and, in the case of the independent candidate, it is emphasized that the candidacy is attained and maintained collectively, even if you do not belong to any party. These interpretations indicate again a strong interest in consolidating as an option through the vote, even if the elections are lost.

Conclusions

As it has been observed, the number of spots does not determine the success of a campaign. MC is among the winners of the elections, it is one of the parties with the largest number of spots -nine-, while the other winner, Pedro Kumamoto only used two; therefore, it would be worthwhile to look beyond the quantitative information.

The first big difference detected among the spots analyzed was that while some parties relied on their candidates to reach the mayor’s office, others decided to position the party, replacing the candidate by an institutional voice or by some public character that would help them attain this aim. MC was the only exception to this tendency, because it was equally important to give prominence to the candidate and to underscore the meaning of “movement” behind the party. In the case of PRI, the strategy was to give the candidate more presence, who was presented as a family man, as a successful economist and alumnus of the Universidad de Guadalajara. Less was spoken about the party as such, only an allusion was made about how good life was in other times.

The parties that relied on positioning the candidate alluded to the political past or public welfare of each of them, trying to extol their good decisions from previous times. To them it was important to say that they were well known, as if knowing someone equated to trusting that person.

When classifying the values, the similarities between political and advertising propaganda became evident, since an entire persuasive proposal could lie in one adjective.

The corpus was rather classical in terms of audiovisual genres and it leaned towards reports and fiction mainly, in addition to the fact that it included video clips as a more risky proposal. While the report helped to highlight the candidate’s qualities and their sympathizers’ testimonies, fiction was more often used by the parties seeking to consolidate their registration. The recreations produced by these parties spoke about how corrupt the government is and the main deficiencies in the city; to later say that the best solution is to vote for their proposals, which are free of vices and ready to put an end to the tragic status quo. Both strategies are strong: while the report tends to be associated with the truth -the genre is rarely questioned-, the contrasts of fiction directly appeal to emotions. In addition to proving to be an innovative genre, the use of the video clip had a clear aim: addressing the young audiences. This was an important issue in these elections, because as it was observed, many parties were interested in attracting the attention of this group, assuming that adults already have their opinion and political affinity, while the young do not join traditional parties so easily -PRI, PAN of PRD- and they seek new alternatives. Requesting their vote by means of the video clip, through music and the presence of other young people proves to be a rather powerful persuasion strategy, provided it is used wisely. Of the three parties that produced video clips, ES and PANAL presented stereotypical young people and phrases that were not very credible to the point of sounding caricatural. MC was more sober, though it was not free from stereotypes either.

In turn, Kumamoto addressed the young directly and a certain group in particular: university students like himself, people who like him understand the problems the district has and the inconveniences of belonging to one party or another. Despite the fact that he only used two spots, his strategy was among the strongest. In the first spot he underscored that he was part of the community of young people who collected signatures to legitimize his candidacy, and in the second he promised that in case he was elected he would lower his own salary 70 %. Both ideas propose an opening towards a new, transparent path.

In the case of the PRD and PT female candidates, they tried to target women in particular, assuming that they would feel automatically identified with them. Nevertheless, it would be necessary to think about whether femininity is represented by vanity, as presented by PRD, or the market as proposed by PT.

Although some spots targeted specific social groups, most intended to approach the citizenry in general, considering the citizen only as a voter and not as an active member of the State. The citizens who appear in the spots expect to receive something in return from the candidates or the parties, mainly something as a gift, not as a right of being listened to by their representatives.

This review of the 50 spots and their comparison between the party and the independent candidate to the local congress allows observing how their respective persuasive strategies were built, but it is not limited to understanding what happened in the electoral contest for the Guadalajara mayor’s office during the Jalisco elections in 2015. The analysis allows us to question the impact of television on political decisions, to reflect how to read persuasive messages critically and reflexively, and to realize how the Mexican political stage needs other proposals that adjust to a more participative and active society than that of a few years ago. That is, this review intends to pose questions that would be worthwhile approaching more precisely in future research. Some aspects that could be explored are: gender representation in the campaigns, the construction of citizenry from the political parties, the differences between the campaigns by successful independent candidates and those by candidates that do not prosper, among others

REFERENCES

Albaladejo, T. (1989). Retórica. Madrid: Síntesis. [ Links ]

Alcalá, F. (2010). Lo irónico-sublime como recurso retórico en el cine de no-ficción de Werner Herzog. El caso de The White Diamond, Grizzly Man y The Wild Blue Yonder. Tesis de doctorado. Universitat Pompeu Fabra, España. Disponible en http://hdl.handle.net/10803/7266 [ Links ]

Alcalá, F. (2016). Los spots televisivos en Jalisco, 2015. Análisis de sus estrategias de persuasión. México: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

Benassini, C. (2016). Cambios a la reforma electoral: ¿para qué tipo de comunicación política? Zócalo, 191, 11-13. [ Links ]

Benet, V. (2015). Mutaciones del cine: la historia cultural y las imágenes supervivientes. Nuevo Texto Crítico, 28(51), 15-29. [ Links ]

Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. (1995). El arte cinematográfico. Barcelona, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Capdevila, A. (2004). El discurso persuasivo: la estructura retórica de los spots electorales en televisión. Barcelona, España: Aldea Global. [ Links ]

Capdevila, A. (2005). Propuesta para el análisis de la propaganda electoral audiovisual. Un modelo retórico argumentativo. Actas do III Sopcom, VI Lusocom e II Ibérico. Volume II. Teorias e estratégias discursivas, pp. 239 -246. Universidade Da Beira Interior, Covilhã Portugal. Recuperado de: http://www.labcom-ifp.ubi.pt/ficheiros/20110829-actas_vol_2.pdf [ Links ]

Corona, J. (2011). Propaganda electoral y propaganda política. Estudios de Derecho Electoral. Memoria del Congreso Iberoamericano de Derecho Electoral. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Dallorso, N. S. & Seghezzo, G. (2015). Inseguridad y política: el miedo como operador estratégico en las campañas electorales en Argentina. Comunicación y Sociedad (24), 47-70. Disponible en http://revistascientificas.udg.mx/index.php/comsoc/article/view/2522 [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. (1984). La imagen en movimiento: estudios sobre cine 1. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós. [ Links ]

Eco, U. (1992). Los límites de la interpretación. Ciudad de México: Lumen. [ Links ]

Goodman, N. (1990). Maneras de hacer mundos. Madrid: Visor. [ Links ]

Hernández, G. (2016). Comunicación política y spots. Zócalo, 191, 14-16. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional Electoral-INE. (2015). Pautas para medios de comunicación Jalisco. Recuperado el 7 de octubre de 2015, de Recuperado el 7 de octubre de 2015, de http://pautas.ife.org.mx/transparencia/proceso_2015/jalisco/index_cam.html [ Links ]

Leyva, O. (Coord.). (2016). El spot político en América Latina: enfoques, métodos & perspectivas. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara-Centro Universitario de la Costa. [ Links ]

Ochoa, O. (2000) Comunicación política y opinión pública. México: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Orozco, G. (1997) El reto de conocer para transformar. Medios, audiencias y mediaciones. Comunicar (8), 25-30. [ Links ]

Perelman, C. (1989). Tratado de la argumentación: la nueva retórica. Madrid: Gredos. [ Links ]

Reardon, K. (1983) La persuasión en la comunicación. Teoría y contexto. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, I. (2003). Estrategias de comunicación electoral en televisión durante el período 1989-2000. Tesis doctoral no publicada. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Recuperada de http://biblioteca.ucm.es/tesis/inf/ucm-t26798.pdf [ Links ]

Ruiz-Collantes, X. (2000). Retórica creativa: programas de ideación publicitaria. Barcelona: Aldea Global. [ Links ]

Tribunal valida candidatura de “Lagrimita”. (2015, 30 de mayo). El Informador. Recuperado el 10 de diciembre de 2015, de Recuperado el 10 de diciembre de 2015, de http://www.informador.com.mx/jalisco/2015/594998/6/tribunal-valida-candidatura-de-lagrimita.htm [ Links ]

Yáñez, J. (2016). El factor Kumamoto. Zócalo, 191, 20-22 [ Links ]

2It is recognized as a risky model since the work by the authors that we selected is not on the same epistemological line, however, we believe that, for the analysis that we are conducting, this interdisciplinary exercise is worthwhile.

3The campaign period spanned from April 5 to June 3, 2015, and the elections were held on June 7 that year. On election day, municipal presidents and representatives to the State Congress were elected. In the case of the municipalities, a candidate per party was presented, except in the case of PRI, which presented their candidate in alliance with the Partido Verde Ecologista de México -the Instituto Nacional Electoral classified all the coalition materials as PRI spots, that is why we do the same here-. The parties and their candidates were: for Partido Acción Nacional (PAN)-, Alfonso Petersen; for Partido Revolucionario Institucional and Partido Verde Ecologista de México (PRI and PVEM), Ricardo Villanueva; for Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), Celia Fausto; for Partido del Trabajo (PT), Beatriz García de la Cadena; for Partido Movimiento Ciudadano (MC), Enrique Alfaro; for Partido Nueva Alianza (PANAL), Antonio Pérez Garibay; for Partido Movimiento por la Regeneración Nacional (MORENA), Jesús Burgos López; for Partido Humanista (HUMANISTA), Leonardo García, and for Partido Encuentro Social (ES), Joaquín Rivera Meza. The sample includes all the spots that explicitly advertised the party candidates (Instituto Nacional Electoral [INE], 2015). There was also the case of an independent candidate for the municipal presidency, citizen Guillermo Cienfuegos -a famous clown that has appeared in Televisa programs in Jalisco for over two decades-, but due to some irregularities in his registration, his candidacy was validated during a great part of the campaign (Tribunal validates “Lagrimita's” candidacy, 2015), that is why he was not considered for this analysis. In the case of the candidates for congress, only Pedro Kumamoto’s spots are considered because it was an independent candidacy without antecedents (Yáñez, 2016). Given that some more general spots were produced by parties with the double objective of advertising both the candidates for municipal offices and the candidates for congress, they were included within the sample selected provided that they did not make any explicit mention to a candidate or representative.

Received: September 27, 2016; Accepted: December 02, 2016

texto em

texto em