Introduction

In the first part of this text we described some stellar moments of the dystocic birth and twisting evolution of the condition known as the metabolic syndrome (MS), signaling, by the way, the myriad of terms used to name it. In this regard, to begin with, when a condition brings together so many names, something is wrong in both conception and/or perception of the underlying phenomenon. The costly epidemiological importance of the MS1-4 requires a frontal combat on the part of medical profession and all the State organs, the executive actions of health agencies, as well as the resolute collaboration of the entire society. As in all battles, in order to set up proper immediate tactics and successful long-term strategies, a clear operational definition and a sharp profile of the enemy is a basic and decisive requirement. It is always desirable, that the name given to the condition we are fighting must be a faithful reflection of its true nature.

The second part of this text on the so-called MS is focused in dissecting the false premises underneath a name that not represent appropriately the physiopathological and clinical nature, and the complexities of this condition.

Why the term «metabolic syndrome» is a misnomer

According with the Thesaurus dictionary,5 the word disease is defined as a «disordered or incorrectly functioning organ, part, structure, or system of the body resulting from the effect of genetic or developmental errors, infection, poisons, nutritional deficiency or imbalance, toxicity, or unfavorable environmental factors». Diseases can be of structural or functional nature, or combination of both. A «structural disease» in opposition to the so-called «functional disease» has a well-defined tissue or organ anatomic abnormality or lesion, and not only a functional disarray. In this context, obesity and overweight (O/O) couple form a perfectly defined structural disease, characterized by the increase of fat mass (hypertrophy or hyperplasia of adipocytes), abnormal distribution of fat (upper or lower body adiposity), and frequently, but not always, adipocyte dysfunction, which in turn attracts and activates invader macrophages, producing both cells a varied series of «rogue» molecules (diverse cytokines, adipohormones, reactive oxygen species, etc,) which can cause extensive functional and organic damages.

Our group has used for a long time the following working definition of obesity: «Chronic disease due to the loss of balance between caloric intake and energy expenditure, characterized by excessive accumulation and abnormal distribution of body fat, frequently but not always associated to structural and functional disturbances of adipocytes, insulin resistance and secondary hyperinsulinism, low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, all of which lead to the development of several morbid conditions affecting multiple organs and systems».6

In turn, syndrome, a word from the Greek «running together» (σύν + δρóμος, sun + dromos), is an associated set of symptoms, signs and laboratory and other diagnostic tests abnormalities, which may be originated by multiple causes. For example, jaundice is a syndrome and not a disease because the elevation of different classes of bilirubin can be the consequence, among other processes, of hepatocellular damage (as in viral hepatitis), massive red corpuscle destruction (hemolytic anemia) or obstruction of the bile duct system (by stones or bilio-pancreatic tumors).

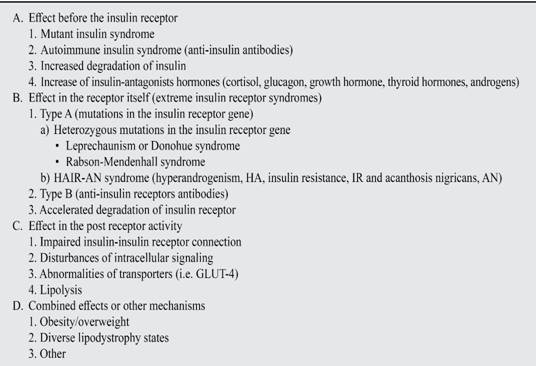

In most cases the functional phenomenon underneath obesity is called insulin resistance (IR), rightly denominated a syndrome, because is a well-defined functional disarray which aside from obesity can be caused by other numerous causes (Tables I and II).7-13

IR is defined as a «state in which a greater than normal amount of insulin is required to elicit a quantitatively normal response».14 In this context it is implicit the secondary effect of hyperinsulinism, a homeostatic response to overcome the poor tissue sensitivity to insulin. The excess of insulin is the responsible cause of many, but not all, physiopathological and clinical manifestations of the syndrome. What we called «clinical conglomerate» is the association of symptoms, signs or paramedical abnormalities which taken separately may be caused by different entities, but assorted are conspicuously related to a single disease or syndrome. Take the case of the «polys» of symptomatic diabetes: polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria. Each of these symptoms may have different origins. Just to mention a simple example, one can be thirsty due to dehydration caused by diuretics, a copious diarrhea or a stormy hangover. But the three polys altogether, in a high proportion of cases, may indicate uncontrolled hyperglycemia, i.e. diabetes. In another example, the conglomerate of syncope, dyspnea and anginal pain, each of which can be caused for multiple diseases or conditions, when grouped in a patient with an expulsive heart murmur, signals vigorously the existence of aortic stenosis («the aortic triad or tetrad»). The difference between syndrome and «conglomerate» is that the set of symptoms, signs and paramedical abnormalities in the former may be caused by several causes, while in the latter there is, mostly, a single one. Of course, the sensitivity and specificity of the «conglomerate» symptoms and signs are less manifest and forceful than in the case of a syndrome.

It is the MS, a disease, a syndrome, or a clinical conglomerate? Clearly, it is not a disease because cannot be directly associated to a well-known disorder specifically affecting the structure or part of a certain functioning organ, or a definite body integrated system. On the contrary, O/O fulfills the defining postulates of a disease, but it is not possible to relate always the MS to it, because under the present «official» definition,15 the diagnosis of the syndrome could be done in the absence of adiposity, and conversely, it is feasible that individuals with O/O may exhibit robust «metabolic health», defined in this context, as the absence of all the definition traits of the MS. Certainly, as it has been mentioned before, the vast number of cases of MS encompasses persons with O/O. This latter condition is frequently associated to insulin resistance (IR), and secondary hyperinsulinism. This pathophysiological circumstance, altogether with other concurrent pathogenic mechanisms, explain the assembled symptoms, signs and laboratory abnormalities, which together compose the clinical complex called MS. The term «syndrome of insulin resistance» cannot be used as subrogate of MS, because as it has been mentioned, there are many other causes of poor insulin sensitivity (Table I), besides abdominal obesity. Also, there are many cases in which IR is not associated to the conglomerate symptoms at all.

IR is indeed a syndrome ¿but MS itself, is it a syndrome or a clinical conglomerate? All depends on the diagnostic criteria adopted. If one accepts the touchstones of the harmonizing criteria15 gathered by an ensemble of organizations (International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity), in which obesity is not an indispensable prerequisite for the MS diagnosis, then, indeed, it is a syndrome, because it may be originated by the obesity-related IR, or in absence of the latter, to any other of the causatives enlisted in Table I, or to the aggregation by chance of independent but confluent defective phenotypes leading to hypertension, dyslipidemia, or dysglucemia. But if we accept the original conception of the IDF,16 in which abdominal obesity is a mandatory criterion for MS, then the referred condition it is not a syndrome, as the only cause of the loss of insulin sensitivity in O/O is adiposity itself. In such case, with a single determinant causing the clinical complex, this one must be considered a «clinical conglomerate». However, even in the case that this complex would be in all cases a syndrome, the second portion of the name «metabolic» is also misleading and confuse. The noun «metabolism» means: «the sum of the physical and chemical processes by which living organized substance is built up and maintained (anabolism), and by which large molecules are broken down into smaller molecules to make energy available to the organism (catabolism)».17 So, the term encloses all vast anabolic and catabolic functions of the body. But if adiposity is considered an indispensable requisite for diagnosing MS, then the term «metabolic» is naturally addressed, in the mind of everyone, to the very well-known metabolic abnormalities associated to O/O, i.e., dysglucemia, dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia, among others. If O/O is not an indispensable criterion for MS, then the term «metabolic» lies in the air without any support: metabolism of what? Even more, several related and common conditions deserve also the name of metabolic syndromes: diabetes, the lipid triad, single hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia, and hyperuricemia. Even in the case that the prefix «cardio» is added to form the term «cardiometabolic syndrome», the name remains imprecise, because all the mentioned pathologies (diabetes, dyslipidemic syndromes and hyperuricemia) also have ominous consequences on the heart, i.e., there are either «cardiometabolic» conditions.

To finish this exposition of ideas about the relationship among the terms disease, syndrome and clinical conglomerate, we must to say that in most of the cases, patients with excessive adiposity have a disease called O/O. Most of them also suffer the obesity-related IR, which is manifested by a clinical conglomerate, known up to now with the name of MS.

What is the purpose of all this intellectual wringing? We are convinced that the concept of MS should be cleaned up and better bound, not only for rational and conceptual reasons, but mainly for a set of practical ones. If we decide to limit the concept of MS to patients with O/O, then the attention of all physicians devoted to the clinical care of these subjects will be focused on adiposity, which is the real physiopathological, clinical and epidemiologic problem. In fact, the main purpose of the authors of the ATP III definition was to emphasize the importance of obesity in order to reduce the risk of its cardiometabolic consequences, i.e., atherosclerotic diseases and DM2. In several papers written by Grundy, one of the leading authors of the ATP III document, it is stated that the text was focused principally in O/O because the couple is a major source of cardiometabolic risk.18-21 Then, obesity must be the center of attention of scientists, clinicians, epidemiologists, and members of other related disciplines, over all the other clinical types of IR, that no matter how intriguing and fascinating they may be, have indeed a much lesser importance from the clinical and public health points of view.

Also, the ordinary obese or overweighed patients with two or more of the comorbidities which are part of the conglomerate needs a different therapeutic approach than lean patients with the same risk factors or the «metabolically healthy» obese persons.

The recognition of the close link between IR and the MS may lead to the assumption that the former is the unique physiopathological mechanism in the genesis of the conglomerate. Notwithstanding, the altered physiology of this condition is rather more complex and tangled. For example, the relation between insulinemia and high blood pressure show some of the difficulties to understand the intricate connections of several physiopathological conditions in both, obesity and the so-called MS. Although Ferranini was one of the first researchers to point out the relation between high blood pressure (mainly diastolic pressure) and insulin resistance and hyperinsulinism,22,23 establishing the presumed hypertensive effects of hyperinsulinism,24 more recent research from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study25 had revealed that «neither insulin resistance nor insulinemia was related to hypertension or blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes in the 3 ethnic groups» (non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and African Americans). It is known that acanthosis nigricans,26 whether associated or not to polycystic ovary syndrome27 and obesity, is a typical IR condition, not necessarily accompanied by hypertension. In US American Indians school-children it has been found that obesity was present in 46% of the studied subjects, 14% of them with the typical skin lesions of acanthosis, but scarcely 9% with hypertension.28 Contrasting the fact that many studies have shown only a weak association amidst hypertension and insulin serum levels,23,29 there is a colossal volume of evidence pointing out the role of obesity by itself in hypertension. For example, prevalence of hypertension which is present in about the 30% of lean subjects, arise its incidence to 60% in overweighed, and to more than 70% in all grades of obesity.30 Hypertension is six times more frequent in overweighed and obese patients than in lean persons.31 It has been observed that a weight gain of 10 kg raises 3 and 2.3 mmHg the systolic and diastolic blood pressures respectively, producing a 12% increase of coronary risk and a 24% of stroke risk.32 Although, certainly there is a close relationship between obesity and IR, the association is not continuous. In this regard, contradictory evidence swamp contemporary medical literature, with some studies showing a linear relationship between both,33 in spite of others which indicate that greater levels of obesity are not associated to more severe IR.34,35 Moreover, Hall et al.36 have described what seem to be the true hypertensive mechanisms of obesity: physically extra and intrarenal compression by visceral and retroperitoneal fat, activation of both the renin-angiotensin system and adrenergic activity, and activation of mineralocorticoid receptor which is independent of the effect of the angiotensin-aldosterone axis. It seems that in the so-called MS, not all the components are direct consequence of IR and abdominal adiposity itself is maybe the most important factor in the generation of hypertension.

For all these reasons we are reluctant to consider all patients with manifestations of MS in the same nosological category and we advocate that the concept be restricted only to O/O patients, getting back to the IDF definition of 2005.

Obesity phenotypes. The wicked moat of language

In a recent research carried out by our group, merging two extensive databases of adults of both genders, pertaining to a contemporary, urban medium class stratum of Mexico City, we studied the relation between the two anatomic-physiologic structural and functional extreme poles of O/O: adiposity in one side, and dysfunctional obese-related metabolism, in the other.37

As it can be seen in Table III, employing the still universal tool of body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), corpulence was assessed in all participants. Fasting blood glucose, serum triglycerides, HDL-C, and blood pressure were also determined. The three classical, standard weight groups, leanness, overweight, and obesity, were in turn broke down, according to the type of «metabolism», in normometabolic (with none of the MS traits), intermediate dysmetabolism (one or two of those factors) and dysmetabolism (three or more of the metabolic features). As we are bundling up «metabolism» with «corpulence or adiposity», the former word is addressed necessarily to the metabolic disorders of O/O.

Table III: Obesity and overweight phenotypes in mexican population.37

BMI = Body mass index, kg/m2. Normometabolism: 0 traits of MS. Intermediate dysmetabolism: 1-2 of the following traits: waist circumference ≥ 90 cm in men; 80 cm ≥ in women, serum triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; HDL-cholesterol < 40 mg/dL in men, < 50 mg/dL in women; fasting serum glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL, blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg). Dysmetabolism; three or more of those traits.

Several important conclusions can be derived from these data: Almost two thirds of the participants were affected by O/O. As the acquisition of these data was accomplished at least three lustra ago, therefore it must be taken into account that the O/O problem become worse nowadays in our country. According with ENSANUT 201238 the prevalence of O/O was 71.3%, of overweight, 38.8%, and of obesity, 32.4%, while in this sample same variables were: O/O, 63.9%, overweight, 42.8, and obesity 21.4%, representing more overweight, although less obesity. In any case, less than 6% of the lean participants of both genders were frankly dysmetabolic, whereas 17.4% with O/O had normal metabolism (12% of persons with overweight and 5.4% of obese people).37

We think that is essential to reconsider the internationally accepted terms describing the four basic phenotypes:37,39-41 lean healthy (LH), obese unhealthy (OU), metabolically healthy obese (MHO), and metabolically obese but with normal weight (MONW). Our study show distinctive prevalence of all these phenotype varieties, quite different to the data provided by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NANHES) 1999-2004.40 The current denominations seem to us aberrant or idiomatically confuse. First of all, if we try to be accurate and precise, using only the adjective obese, we are automatically letting out overweighed patients. As the term «healthy obese» is an oxymoron (a phrase that uses two contradictory words) because if obesity is a disease, there is no possibility that such pathological condition could be tied to health, consequently the phrase obese unhealthy is a pleonasm, because every obese is unhealthy for definition. The worst of all those terms is the sentence metabolically obese but with normal weight, because it is too long, imprecise and contradictory. Obesity is a structural disease, frequently associated to the metabolic derangements that we have discussed, but not always. We propose that instead of these problematic denominations, we use a simple system which takes in consideration the aforementioned dipole: in one side, an anthropometric measure, BMI, and its three operational categories: leanness, overweight and obesity, which reflect the presence and/or severity of adiposity with more or less accuracy, and in the opposite side, the metabolic status: normometabolic, intermediate dysmetabolic and dysmetabolic, as they were described before. Table III shows the nine phenotypes composed by the combination of both poles: anthropometry and metabolism, yielding to a more precise characterization of these clinical complexes. Furthermore, this categorization has clinical and preventive applications. For example, it can be seen that two third of lean persons had intermediate dysmetabolism. This discrete metabolic disorder indicates that these «normal» weighed subjects probably had already a disturbed metabolism, facing therefore certain danger of developing the full-blown dysmetabolic derangement with the gain of just a few kilograms, as well as a greater cardiovascular and cardiometabolic risk than lean normometabolic subjects. It would be important to set up in them a vast strategy of education, consciousness-raising, appropriate treatment of all derangements, and close follow-up, to delay or abort the apparition of the full metabolic complex. What we called intermediate dysmetabolic overweight or obesity, has been recognized by other authors and named as pre-metabolic syndrome.42,43 On one hand, the prefix pre is also misleading (as are the terms pre-diabetes and pre-hypertension) because not always the intermediate state evolves to the full-blown metabolic derangement. But more important is the fact that if such stage is labeled as a pre-morbid condition, then affected persons or their physicians may not have the sense of urgency necessary to assume a preventive or therapeutic conscience. In the proposed nomenclature, the term intermediate dysmetabolism states doubtlessly that it already exist a metabolic disorder.

Conclusions

The term MS is not just an abstract idea or a philosophical entelechy. On the contrary, it represents a concrete, material and dynamic circumstance susceptible to be measured, categorized and understood through numerical values. The importance of this clinical concept rests in its capacity to identify properly long-term high-risk subjects, highlighting the role of abdominal adiposity as the fundament of the complex. On fulfilling this task, it may bring forth a clear therapeutic and preventive conscience among patients, medical care providers, and health policy-makers. Due to the extraordinary complexity of the underlying condition, the term knots up several really complicated phenomena (the multiple biological actions of insulin, the adipocyte function and dysfunction, the complex hunger control, the energetic metabolism, the role of several hormones and cytokines, the consequences of the chronic inflammatory state and redox reactions, among many others) hard to perceive and understand for the standard physician, meaning that metabolism and cardiovascular experts have to oversimplify the concept in order to convert it in a useful clinical tool of universal and practical application. In addition, the constant modifications of its definition, the pronunciation of its premature death, followed by other statement announcing its rebirth, alongside with the loose application of the term to a minority of lean subjects with RI of other origin, make-up the concept of MS a fussy puzzle whose contradictions do not help to its clinical understanding and application.

In resume, we propose that the term MS be replaced by the denominations based on the recognition of the aforementioned anthropometric/metabolic dipole: dysmetabolic overweight or obesity . The terms had to be restricted to obese or overweighed subjects, with at least two of the other diagnostic features of the condition. As a secondary salutary effect of the change of denomination, the various leanness-overweighed-obesity phenotypes would acquire more rational and less bizarre names, based in the two structural and physiopathological arms (dysmetabolism and anthropometry) which are the columns that support the whole concept of what nowadays we know as the «metabolic syndrome».

There is a saying in politics that establishes that the form is the content. We think that in medicine as well as in basic and applied sciences, this old principle is absolutely pertinent. The name we want to give to distinct phenomena or conditions (the form) must define neatly and unequivocally the true essence of them (the content). So, amending the famous Juliet´s phrase we can respond to her question: What’s in a name? In the name should reside the profound and veritable meaning of the word: a rose is a rose, and nothing else. And whenever we listen that name, the conception of its colorful essence and sweet aroma is awakened in us.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)