Introduction

Basic life support (BLS) are a group of maneuvers which constitute a fundamental tool to save lives, especially if the emergency occurs out of a hospital.(1)-(4) The knowledge and skills that must be acquired in this area are indispensable for those who dedicate themselves to health care, as well as, for those who are linked to this field,(1),(3),(5),(6) since if they are applied correctly, survival rates may be optimal.(7),(8)

Several publications on the knowledge level about BLS in health personnel reveal disappointing results, with a frequency of unawareness of these maneuvers between 41.7% and 57.3%.(1),(3),(7),(9) The findings in Latin America and locally are similar -but more worrying-, since inadequate knowledge in both theoretical and practical BLS goes from 58.8% to 92%, including practitioners, such as doctors and nurses.(6),(10)-(12) Researches have proved that starting training in undergraduates improves theoretical knowledge and physical skills for proper execution of BLS(5) contributing to reduce the increased levels of morbidity and mortality in population that suffers cardiopulmonary arrest,(13)-(15) which is frequently the primary cause of death. However, in our search we found no studies that address this issue in our context.

Therefore, the main objective in our study was to determinate the knowledge level about BLS in medical students from nine Peruvian universities, as well as its associated socio-educational factors. Thus, once identified, propose solutions to this problem.

Material and methods

Design and Subjects

A cross sectional multicenter study was conducted during 2013-2014, over undergraduate medical students from nine Peruvian medicine schools. Universities included were: Universidad Nacional de Piura-Piura, Universidad Nacional del Altiplano-Puno, Universidad Particular Antenor Orrego-Trujillo, Universidad Católica Santa María-Arequipa, Universidad Nacional de Ucayali-Ucayali, Universidad César Vallejo-Piura, Universidad Nacional de Ica-Ica, Universidad San Pedro-Chimbote y Universidad Pedro Ruiz Gallo-Lambayeque. All regular students were invited to participate (Figure 1).

Measurements and variables

The final questionnaire was composed of two sections.

Demographic and academic data

Gender, age, marital status, university of origin, year of study and academic cycle coursing at the time of the survey. They were asked about their participation in a course where they were instructed in BLS techniques, management of medical first aid or any about injection administration (as in some of these courses the topic of BLS is touched, due to adverse reactions of the injection of drugs or the maneuvers that must be performed in emergency situations). Coursing clinical sciences, academic stages were defined to students who said they were carrying courses including hospital rotations (from third to sixth year of medical career). It was considered as a desire to be trained in practical BLS maneuvers to those who said they wanted to be both theorical and practical instructed.

Questionnaire for knowledge evaluation

The second section included twenty questions that measured the knowledge level about BLS, structured as multiple choice and single answer. To measure the knowledge level it was considered a scale from 0 to 20, considering as passing grade to those who obtained 11 or more adequately answered questions. For the analysis, it was considered as dependent variable to have passed the test. The independent variables were socio-educational data formulated in the questionnaire and were used to determinate whether there are differences according to these variables.

We generated this questionnaire in Spanish, based in ILCOR/ERC/AHA 2010 Guidelines. It was initially formulated by three of the authors of this study, one of them with five years of experience in BLS field and a master's degree in research; the second one, with a master's degree in research and member of the scientific evidence generation team at the National Health Institute of Peru; and the last one, past AHA physician in Peru. Validation and evaluation of the questionnaire reliability was performed in several stages. Firstly, expert judgement was used, in which participated three physicians with international accreditation for BLS, who evaluated the relevance of the items based in an ordinal scale (adequate or not adequate) and assessed the formulation quality of each question, considerating a discrete scale (0 = poor quality to 10 = excellent quality), based on the scores of each average, the items were excluded or included and modified. After this process 5 items were eliminated. Subsequently, the comprehension of each question was evaluated over a pilot sample of 63 medical students with an ordinal/discrete scale (0 = no understandable y 1 = totally understandable), those items with average score under 5 were modified. The modified instrument was applied over 198 students in order to get a basal measurement, after three weeks the instrument was applied once more without any educational intervention over the same students, to evaluate the test-retest reliability. Afterwards, an educational intervention on BLS knowledge was performed and again the questionnaire was applied, in order to evaluate sensitivity on post-intervention change. 198 individuals were included since the questionnaire consists of 20 items. After this whole process, three medical experts with international accreditation in BLS evaluated the instrument providing compliance.

Finally, the scores range from 0 to 20 points, in that way, according to what was suggested by the Ministry of Education of Peru, the knowledge was categorized as adequate (11 to 20) and inadequate (0 to 10).

Data collection procedures

Pollsters were summoned trough contacts made in Peruvian Medical-Student Scientific Society (SOCIMEP), ensuring to count with both public and private universities from the largest departments in the inner regions of Peru, a training process to solve any doubts was performed; and a group of instructions that specified step by step through the interview process was delivered.

Each pollster was instructed for applying the questionnaire in free hours of academic activities and for answering participant's doubts. It was an auto-applied questionnaire and respondents offered their consent verbally before solving it, after the explanation of the aim of the study provided by the delegates of the venues.

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the San Bartolome National Hospital (Official Letter No:1544-DG-OADI-N°333-HONADOMANI-SB-2103).

Statistical data analysis

We created a database in Microsoft Excel Version 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, CA, USA) by independent and double fingering; databases had a good concordance in quality control. This database was imported into the software STATA 11.1 (Stata Corporation, TXT, USA).

For categorical variables, it was performed a description of the variables, the dependent variable (according to the number of correct answers obtained in the questionnaire) and independent variables (gender, age, marital status, university of origin, previous related courses, desire to be trained in practical BLS), using frequencies and percentages. For the numerical variable (age) the median and interquartile range was used, according its distribution evaluated with Shapiro Wilk test.

We used a 95% confidence interval. We performed generalized linear models with binomial family and link log function; all models were adjusted using the university under study as cluster. Both crude prevalence rates (cPR) and adjusted prevalence rates (aPR) were obtained, as well as, confidence intervals at 95% and p values. The data used in bivariate models and the final model were calculated taking the variables that had complete data (n = 1,270) into account. It was considered as statistically significant a p < 0.05 value.

Results

Characteristics of participants

1,564 medical students participated. The median age was 20.7 years old (range 16-40 years old), 791 (54.2%) were male gender, first and third year focused the main amount of students and it was the sixth year that had fewer respondents, 70 (4.9 %).

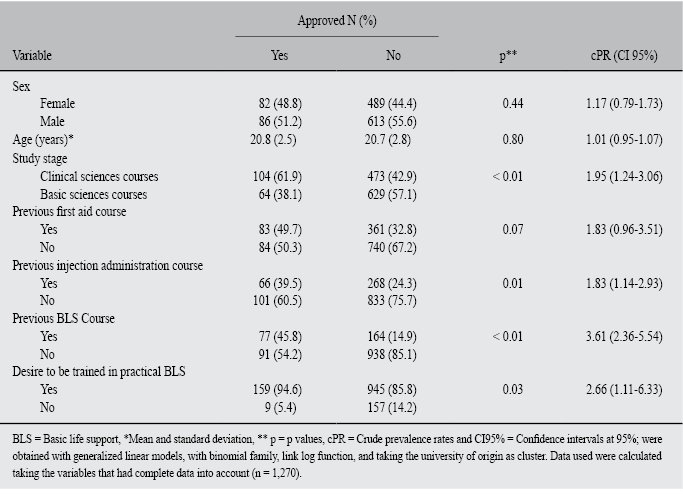

Of all respondents, 1363 (87.1%) failed the BLS test. Of 201 who passed the test, 112 (62.9%) were in clinical sciences semesters, 82 (42.9%) had received a BLS course previously and 174 (94%) said they wanted to be trained in BLS. Participants' socio-educational characteristics are shown in table I.

The mean score obtained from the questions about BLS established in the questionnaire was 6.29; nineteen students scored zero (0) and two obtained the highest score achieved (16 points). Of all students only 1.5% represented the upper third of the scale (score ≥ 14). Private universities obtained pass rates of 15.9% while public only 9.4%.

Association between knowledge level and socio-educational variables

In bivariate analysis was found association between passing the test and coursing clinical sciences (p < 0.01), having received a previous course of injection administration (p = 0.01), a previous one on BLS (p < 0.01) and having the desire to be trained in practical BLS (p = 0.03). Association of socio-educational variables according to passing the test is shown in table II.

In multivariate analysis, passing the test was associated with coursing semesters belonging to clinical sciences academic stages (p: 0.02; aPR: 1.82; CI 95%: 1.11-2.98) and having received a previous course of BLS (p < 0.01; aPR: 2.96; CI 95%: 2.18-4.01), adjusted for respondent´s age and sex, as well as, having received a previous injection administration or first aid course and manifesting the desire to be trained in practical BLS (Table III).

Discussion

Based on our results, approximately one in ten tested students had a good knowledge level about BLS. These findings are within the range found in similar populations to which we evaluated.(6),(10)-(12) This is an unexpected result, because university curricula should ensure the necessary knowledge in undergraduate stage, since in some years respondents will become part of the national health system and may not know how respond well to a situation in which the application of BLS will be required.

We found association between passing the test and coursing practices in hospitals. Several studies, about BLS, shown that the knowledge level increases in direct relationship as medical students move toward superior cycles.(3),(5),(12) A study in a quite similar population agrees with these results, reporting a strong association between the level of knowledge on the subject of medical emergencies and the student academic stage, being the group with lower scores the one where the student was coursing basics sciences.(5) Likewise, when the perception of knowledge was studied, a result in France showed that less than a third of students taking clinical courses perceive that they are qualified to carry out a resuscitation.(16) This could indicate that while the academic stage is an important factor in the formation of the medical student, simple contact with patients is not sufficient to adequately perform BLS, therefore it would be necessary that the student is faced with real or hypothetically real situations to achieve this goal.

Those participants who received a previous BLS course had better scores, in comparison with those who did not received this preparation. In similar populations has been shown that previous basic life support maneuvers in general training, improve theorical knowledge, and practical and physical skills.(1),(3),(5),(7),(8) In populations of physicians, nurses(10)-(12),(17) and people not related to health field,18 previous training in BLS had a positive effect in theoretical knowledge; however, if such preparation is not continuous then knowledge becomes unsatisfactory at the end, even when those trained would obtain a better response than non-trained in baseline and intermediate measurements.(13),(19) A study in nurses showed that previous training on BLS does not ensure better response to cardiac arrest, with a failure rate of up to 84%, this being due to the lack of continuous training in BLS maneuvers.(20) This suggests the importance of continuous training in these maneuvers,(21) although many times it is initiated by the person concerned, is indispensable for an acceptable knowledge level.(7) Continuous medical education in this field, is also necessary to maintain this level constant, since it has been shown that the decay of theoretical knowledge begins six weeks after completing a course and decreases as the time passes.(10),(22)-(26)

Although multivariate analysis did not turned out to be statistically significant, it is important to mention that in bivariate analysis it was found that, those who had the desire to be trained in BLS had a better knowledge level about BLS, remembering that almost all participants had this desire for training. Some studies with population with similar characteristics -but smaller ones- reported interest in the majority of the students in receiving updates on BLS.(3),(10),(12),(27),(28) A study in secondary schools in Northern Europe found predisposition in 4 out of 5 students to perform resuscitation maneuvers in case of facing cardiac arrest. This should be studied in detail, in research that have this goal and more variables that attempt to explain the desire and interest in training in BLS.

Overall, results describe a college student population with a poor knowledge level about BLS, but improves its level as they advance through the academic stages and with previous training in the subject, besides that, they show more willingness to participate in training BLS courses, eager to acquire knowledge and/or improve the one they had already acquired as undergraduates, this would improve their chances to respond to cardiopulmonary arrest. The data obtained in this study come from a large sample of students, evaluating an academic issue that should always be considered in the training of future physicians. Although it is true that the findings do not allow inferring conclusively to all Peruvian medical students, there is at least one major exploration on relevant student characteristics that influence their current knowledge.

The limitation in our study was the use of a convenience sampling, due to the fact that in private universities it is not possible to have access to official lists, since their data protection policy, therefore it is not possible to infer regarding participating universities. Nevertheless, we consider that the data are now a reference, because we sought that in participating universities the survey would be applied in proportion to the actual number of students per year. Another limitation was that we did not obtain other socio-academic variables, so we recommend that future researches explore more associated factors.

We conclude that the knowledge level about BLS in medical students from the universities under evaluation is poor. This is associated with academic stage and having received previous BLS instruction. We recommend that universities in our country consider these results, in this way they can measure the knowledge level of their students and evaluate the possibility of including BLS training in the curricula, as part of the training of the future health professional, as well as ensuring continuous training in this subject.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)