Introduction

Genetic resources of wild species related to cultivated plants constitute a gene pool that can help to solve agricultural problems (Hernández-Verdugo et al., 1998). To be able to cultivate a wild species it is necessary to modify the genetic scheme resulting from natural selection processes to one adapted to human-managed conditions (Hernández, 1985). Such manipulation allows man to adapt biological diversity to the needs of human society (Casas and Caballero, 1995) and is carried out through artificial selection, which in parallel also results in the evolutionary process of domestication (Mastretta-Yanes et al., 2019). For Gepts and Papa (2003), domestication is a continuous genetic selection process exercised by humans during the adaptation of plants and animals; this process generated morphological, physiological and genetic changes known as domestication syndrome (Gepts, 2005; Pickersgill, 2007).

Crops vary within and between species in their degrees of domestication. All known accessions of Capsicum pubescens have large fruits that have lost their dispersal mechanism, and this species occurs only in cultivation. The four other species of domesticated chili pepper each includes a range of variation from wild peppers, through cultivated peppers with somewhat larger fruits that are still capable of natural dispersal, to fully domesticated peppers with large fruits that remain firmly attached to the parent plant after maturity. Clement (1999) proposed two intermediate categories, incipiently domesticated and semidomesticated, to cover the spectrum of changes resulting from human interactions with species of tree fruits in Amazonia. Semidomesticated also fits the situation described by Casas et al. (1998) for Stenocereus stellatus, a giant cactus exploited and cultivated for its fruit in the Tehuacan Valley of Mexico. Casas (1998) considered that such changes in allele frequencies resulting from human selection constitute at least incipient domestication.

The Capsicum genus includes around 25 species belonging to the Solanaceae family (Meckelmann et al., 2015); of these, five species have been domesticated in at least two geographical regions of the new world (C. annuum and C. frutescens in Mesoamerica; C. baccatum, C. pubescens, and C. chinense in South America) (Loaiza-Figueroa et al., 1989; Pickersgill, 2007). Of the five domesticated species, C. pubescens Ruiz & Pav. is one of the main native species cultivated in the Andes (DeWitt and Bosland, 2009). Recent studies indicate that its cultivation and domestication began approximately 6000 years BC in the mid and high regions of Peru and Bolivia, at altitudes ranging from 1300 to 3000 masl (Ruiz and Pavon, 1799). C. pubescens is commonly known as “Rocoto” in Peru and “Locoto” in Bolivia (Meckelmann et al., 2015), and as “Manzano” and “Cera” in Mexico (Pérez-Grajales et al., 2004), due to its shape and appearance.

In Mexico, C. pubescens is distributed throughout the temperate areas of the states of Puebla, Michoacan, Mexico, Oaxaca and Veracruz. It is generally grown in production systems associated with fruit trees such as coffee (Coffea arabica L.), banana (Musa spp. L.), apple (Malus domestica Borkh.), peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch.), avocado (Persea americana Mill.), as well as some lumber species like cedar (Cedrus spp.) and ilite (Alnus acuminata Kunth.), among others. Capsicum pubescens is a perennial plant with purple flowers and hard-headed black seeds (Leyva-Ovalle et al., 2018). Its growth habit can be determined or undetermined, with trichomes in stems and leaves (Pérez-Grajales et al., 2004). Fruits vary greatly in size, shape and color (DeWitt and Bosland, 2009; Leyva-Ovalle et al., 2018; Rick, 1950; Yamamoto et al., 2013).

The fruits are rich in vitamins (A, C and B6), β-carotene, flavonoids, capsanthin, among others (Liu et al., 2013); also, the antioxidant properties of carotenoids protect against diverse heart diseases and cancer (Rodríguez-Burruezo et al., 2009). Likewise, the fruits can be dehydrated and used as a condiment in different dishes (Oboh et al., 2007). Because of this, the consumption of this fruit has grown in recent years as a consequence of increasing Latin American populations in the United States of America and Europe, as well as the increasing interest in functional foodstuffs (Pérez and Castro, 2008; Rodríguez-Burruezo et al., 2009).

There are few papers on the cultivation and distribution of C. pubescens, especially in Central America, where it has diversified. The influence of environmental, geographical, and soil conditions associated with its ecological niche is unknown; therefore, this study was carried out to elucidate the ecological niche conditions, to determine potential growing zones in Mexico, and to describe the possible relationships between the environment and the morphological characteristics of the fruit, as revealed by its current distribution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and data collection

The field work was carried out from October 2016 to March 2017 in 13 municipalities of the central region of the state of Veracruz, Mexico (Table 1, Figure 1). A total of 44 accessions of C. pubescens were obtained; the geographical coordinates of each site were registered to be used as occurrences to build the model.

Table 1 Accessions evaluated in this study.

| Id | Accesion | Municipality | Origin | Farmer name | Altitude | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MEXUVDC1 | Coscomatepec | Dos caminos | Miguel Milian Ramos | 1454 | 19.04419 | -97.03058 |

| 2 | MEXUVCAL1 | Calcahualco | Calcahualco | Roberto Reyes M | 1762 | 19.12128 | -97.08269 |

| 3 | MEXUVCAL2 | Calcahualco | Calcahualco | Marcelino Espinoza de la Cruz | 1680 | 19.12000 | -97.07697 |

| 4 | MEXUVCAL3 | Calcahualco | Calcahualco | Marcelino Espinoza de la Cruz | 1708 | 19.11708 | -97.07697 |

| 5 | MEXUVCV1 | Calcahualco | Cruz Verde | Estanislao García | 1927 | 19.13417 | -97.10750 |

| 6 | MEXUVCV2 | Calcahualco | Cruz Verde | Remigia Ortiz Hernández | 1923 | 19.13306 | -97.10556 |

| 7 | MEXUVTE1 | Alpatlahuac | Teacalco | Manuela Martínez | 2570 | 19.11417 | -97.16556 |

| 8 | MEXUVCO1 | Alpatlahuac | Cocalcingo | Amalia Martínez | 1990 | 19.09272 | -97.10944 |

| 9 | MEUVTL1 | Alpatlahuac | Tlatelpa | David Dorantes | 1799 | 19.11667 | -97.08528 |

| 10 | MEXUVTEPE1 | Zongolica | Tepetitlanapa | José Ismael Vallejo Chimalgua | 1523 | 18.64172 | -97.01292 |

| 11 | MEXUVTEX1 | Texhuacan | Texhuacan | Matilde Tepole Xalamihua | 2019 | 18.62193 | -97.04673 |

| 12 | MEXUVBP1 | Mixtla de Altamirano | Barrio Primero | Evaristo Mayahua Flores | 1678 | 18.60077 | -96.99268 |

| 13 | MEXUVLA1 | Texhuacan | La Aposteca | Félix Cano Hernández | 1431 | 18.61490 | -97.00960 |

| 14 | MEXUVCG1 | Chocamán | Colonia la Garita | Anonymous | 1332 | 19.00816 | -97.02664 |

| 15 | MEXUVBJ1 | Coscomatepec | Barranca de Jamapa | María Antonia Tentle Morales | 1365 | 19.09937 | -97.03216 |

| 16 | MEXUVTEP1 | Huatusco | Tepampa | Francisco Huerta Ballona | 1716 | 19.13524 | -97.02220 |

| 17 | MEXUVTEP2 | Huatusco | Tepampa | Lázaro Huerta Rodríguez | 1743 | 19.14219 | -97.02421 |

| 18 | MEXUVTEN1 | Huatusco | Tenejapa | Anonymous | 1404 | 19.13699 | -97.00624 |

| 19 | MEXUVTEN2 | Huatusco | Tenejapa | María Luisa Sánchez Marinero | 1373 | 19.13587 | -97.00200 |

| 20 | MEXUVTZ1 | Tehuipango | Tzacoala Primero | Agustina Calihua Panzo | 2090 | 18.53895 | -97.07902 |

| 21 | MEXUVTLA1 | Tehuipango | Tlalchichilco | Pascuala Panso Chipahua | 2369 | 18.54041 | -97.05128 |

| 22 | MEXUVTLA2 | Tehuipango | Tlalchichilco | Pascuala Panso Chipahua | 2369 | 18.54041 | -97.05128 |

| 23 | MEXUVTE2 | Alpatlahuac | Teacalco | Alejandro Gómez | 1825 | 19.10950 | -97.09961 |

| 24 | MEXUVTL2 | Alpatlahuac | Tlatelpa | David Dorantes | 1803 | 19.11697 | -97.08578 |

| 25 | MEXUVCO2 | Alpatlahuac | Cocaltzingo | María Martínez | 1968 | 19.09156 | -97.10953 |

| 26 | MEXUVBV1 | Tepatlaxco | Buena Vista | Roberto Sánchez Hernández | 1457 | 19.04153 | -96.87311 |

| 27 | MEXUVTE3 | Alpatlahuac | Teacalco | Gerardo Torres | 1825 | 19.10983 | -97.09953 |

| 28 | MEXUVCV3 | Calcahualco | Cruz Verde | Anonymous | 1934 | 19.13447 | -97.10783 |

| 29 | MEXUVCV4 | Calcahualco | Cruz Verde | Vicente Espejel | 1939 | 19.13614 | -97.10978 |

| 30 | MEXUVTER1 | Calcahualco | Terrero | Rosalino | 1913 | 19.13192 | -97.10344 |

| 31 | MEXUVCV5 | Calcahualco | Cruz Verde | Remigia | 1940 | 19.13611 | -97.10975 |

| 32 | MEXUVTER2 | Calcahualco | Terrero | Diocleciana | 1914 | 19.13194 | -97.10333 |

| 33 | MEXUVTER3 | Calcahualco | Terrero | Serafina | 1914 | 19.13192 | -97.10339 |

| 34 | MEXUVTET1 | Coscomatepec | Tetlaxco | Cirilo Roque | 1678 | 19.03711 | -97.06344 |

| 35 | MEXUVTET2 | Coscomatepec | Tetlaxco | Juan Alejo Rosales | 1683 | 19.03692 | -97.06258 |

| 36 | MEXUVHU1 | Soledad Atzompa | Huixtitla | Leticia López Flores | 2514 | 18.71276 | -97.16385 |

| 37 | MEXUVNE1 | Camerino Z. Mendoza | Necoxtla | Margarita Pérez Flores | 2045 | 18.77791 | -97.15361 |

| 38 | MEXUVCU1 | Tehuipango | Cuauyolotitla | Gines Panzo Panzo | 2387 | 18.51914 | -97.06378 |

| 39 | MEXUVCU2 | Tehuipango | Cuauyolotitla | Gines Panzo Panzo | 2408 | 18.51906 | -97.06331 |

| 40 | MEXUVTZ2 | Tehuipango | Tzacoala Primero | Anonymous | 2108 | 18.53874 | -97.08197 |

| 41 | MEXUVTEH1 | Tehuipango | Tehuipango | Anonymous | 2393 | 18.51947 | -97.05444 |

| 42 | MEXUVVH1 | Tlaquilpa | Vista Hermosa | Lucía Clemente Sandoval | 2592 | 18.59497 | -97.12811 |

| 43 | MEXUVCA1 | Tlaquilpa | Capillatixtla | Jerónima Rosales | 2410 | 18.61050 | -97.11708 |

| 44 | MEXUVDA1 | Tlaquilpa | Desviación Atempa | Félix | 2226 | 18.60092 | -97.10422 |

Sources: Esri, HERE, Germin, Intermap, increment P Corp., GEBCO, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, IGN Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), swisstops Ⓡ OpenStreetMap contibutiors, and the GIS User Community.

Figure 1 Geographical distribution of 44 C. pubescens accessions from the central region of the state of Veracruz, Mexico in two contrasting zones, A and B.

Characterization of C. pubescens fruits

Fifteen fruits at harvest maturity stage were collected from each site. Each of the fruits was morphologically characterized based on descriptors of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, 1995). Traits registered were length fruit (Lenfru) in cm, width fruit (Widfru) in cm, weight fruit (Wefru) in g, pedicel length (Lenped) in mm, wall thickness (Thfru) in mm, placental length (Lenpla) in cm, and number of seeds (Numsed).

A multivariate technique of partial least squares regression (PLSR) was applied, which allows describing the populations considering several morphological characteristics simultaneously, without failing to consider the relationship existing between them. This analysis is useful to predict a set of dependent variables (morphological characteristics) from a set of predictor variables (bioclimatic layers) (Gaviria et al., 2016).

Species distribution model

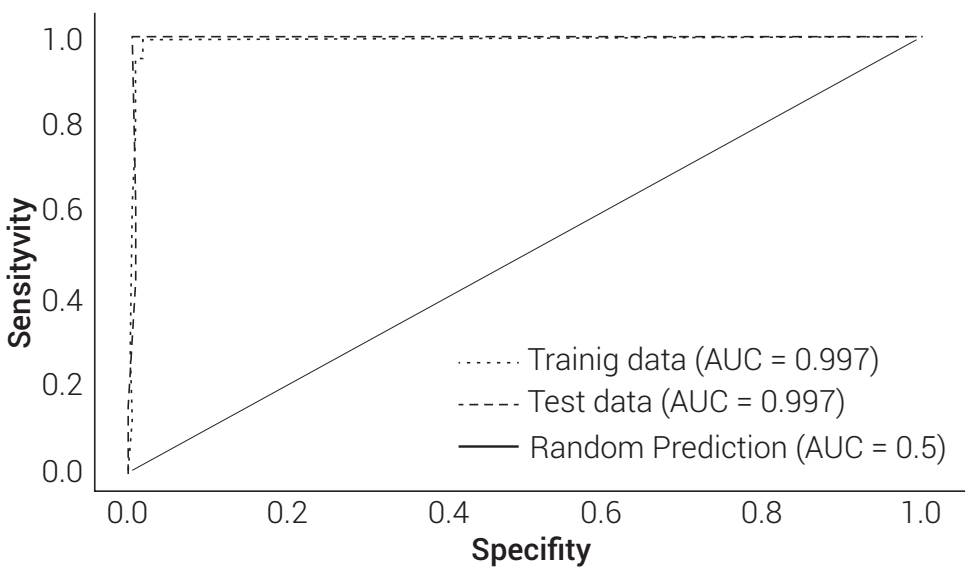

The species distribution model (SDM) was used to predict suitable areas for C. pubescens in places where it occurs. In this model, the locations of the current known distribution of C. pubescens are grouped. Four climatic prediction variables were selected: mean annual temperature (Bio1), annual rainfall (Bio12), altitude (DEM), and a potassium (K) layer as soil property (Bugarín-Montoya et al., 2002; Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2014). These variables were taken from the spatial databases from http://www.worldclim.org (Hijmans et al., 2005). The estimation of the ecological niche was carried out through the maximum entropy algorithm, MaxEnt® Ver. 3.3 (Phillips et al., 2006). Once the potential distribution map was obtained, it was exported to the ArcMap® Versión 10.5.1 software (ESRI, 2017) for contextualization and image manipulation. The quality of the model was evaluated with > 0.9 values of the area under the curve (AUC), which characterizes the performance of the model. The result is a graph output that shows the discrimination capacity of a given presence (sensitivity) versus the discrimination capacity of a given absence (specificity) (Phillips et al., 2004).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

C. pubescens presence sites

Forty-four sites were identified with the presence of C. pubescens in the studied area. Using the coordinates, a distribution map was generated and two regions, A and B, were identified (Figure 1). Region A included the municipalities of Zongolica, Tlaquilpa, Texhuacan, Mixtla de Altamirano, Camerino Z. Mendoza, Soledad Atzompa and Tehuipango; region B included the municipalities of Calcahualco, Alpatlahuac, Chocamán, Coscomatepec, Huatusco and Tepatlaxco.

Region A has a Cf type climate, temperate humid with rains throughout the year, exceeding 2200 mm per year (> 18 % of winter rain), with little thermal oscillation (5 to 7 °C). Region B posesses a Cw type climate, temperate sub-humid with rains in the Summer, with more than 800 mm per year (< 10.2 % of winter rain), with isothermal oscillation range (< 5 °C) (Díaz et al., 2006; García, 2004). Both regions have altitudes ranging from 1300 to 2700 masl, places where the maximum rainfall arises as a result of the discharge of water by warm air masses from the sea (Krasilnikov et al., 2013). They also have an average annual temperature between 5 to 18 °C, while in the coldest month between -3 to 18 °C (García, 2004; SEMARNAT, 2006).

Ecological niche model for C. pubescens

The efficiency of the model reached an AUC value over 0.997, indicating that the ability of the model to classify presences was consistent in the prediction of the ecological niche (Baldwin, 2009; Phillips and Dudík, 2008). The results of the test data (P = 0.5) revealed that the model obtained is better than a randomized model, since the curves are located at the upper left corner (Figure 2) and indicate that there is no error of omission (100 % sensibility) and no error of commission (100 % specificity) (Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2014). These results indicate that the samples were viably taken from the population and that they are truly representative, as there is no ambiguity in the prediction of the ecological niche for C. pubescens. In biological terms, the model reflects reliability, providing useful information for a breeding program. In this regard, Pearson et al. (2007) mentioned that few presences can give enough information for the MaxEnt model to produce acceptable predictions for the distribution of a certain species.

To this regard, the potential distribution of C. pubescens shown in the map of Figure 3, reveals that the best conditions of occurrence are found in the mountainous regions of Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, and Hidalgo, Mexico (Figure 3B); however, a new registry was found in southern Veracruz, at the San Martin Sierra and the Santa Martha Sierra in the Tuxtlas region, at an altitude of 1500 masl (Figure 3B). From an ecological standpoint, C. pubescens is distributed in temperate regions, which coincide with areas of dense vegetation and subtropical forests. This is consistent with the reports on its distribution and habitat (Yamamoto et al., 2013).

Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA.

Figure 3 Potential distribution area of C. pubescens in Mexico, as predicted by the maximum entropy model (MaxEnt).

The model revealed other areas where the presence of C. pubescens is unknown (Leyva-Ovalle et al., 2018). These areas showed a restricted habitat potential, like the Sierra Madre Oriental and Sierra Madre Occidental in the states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon and Chihuahua, Mexico, at an altitude gradient between 2200 and 2700 masl (Figure 3A).

According to the analysis of the contribution of each variable provided by the MaxEnt model, it was found that the variables with larger contribution to the model when they are used separately were annual rainfall (Bio12) with 43.9 %, potassium layer (K) with 23 %, altitude (DEM) with 22.3 %, and mean annual temperature (Bio1) with 10.7 %. This suggests that C. pubescens achieves good growth and development in temperate zones with high rainfall; however, the presence of low temperatures and frost at higher altitudes may limit its distribution (Soto and Geissert, 2011). Furthermore, the species grows on pyroclastic sediments, in acidic volcanic ash, which explains the high content of K, an element that is highly resistant to weathering (Krasilnikov et al., 2013). On the other hand, the humid conditions in areas where the species grows promote the acidity of the soil (pH = 4.2), and together with their mountainous relief, they cause erosion and loss of nutrients (Krasilnikov et al., 2013; Medina et al., 2010; SEMARNAT, 2006), demonstrating their adaptation even under these conditions; in this sense, the use of ecological niche models contributes to a better understanding of the relationships between species and the environment (Parolo et al., 2008).

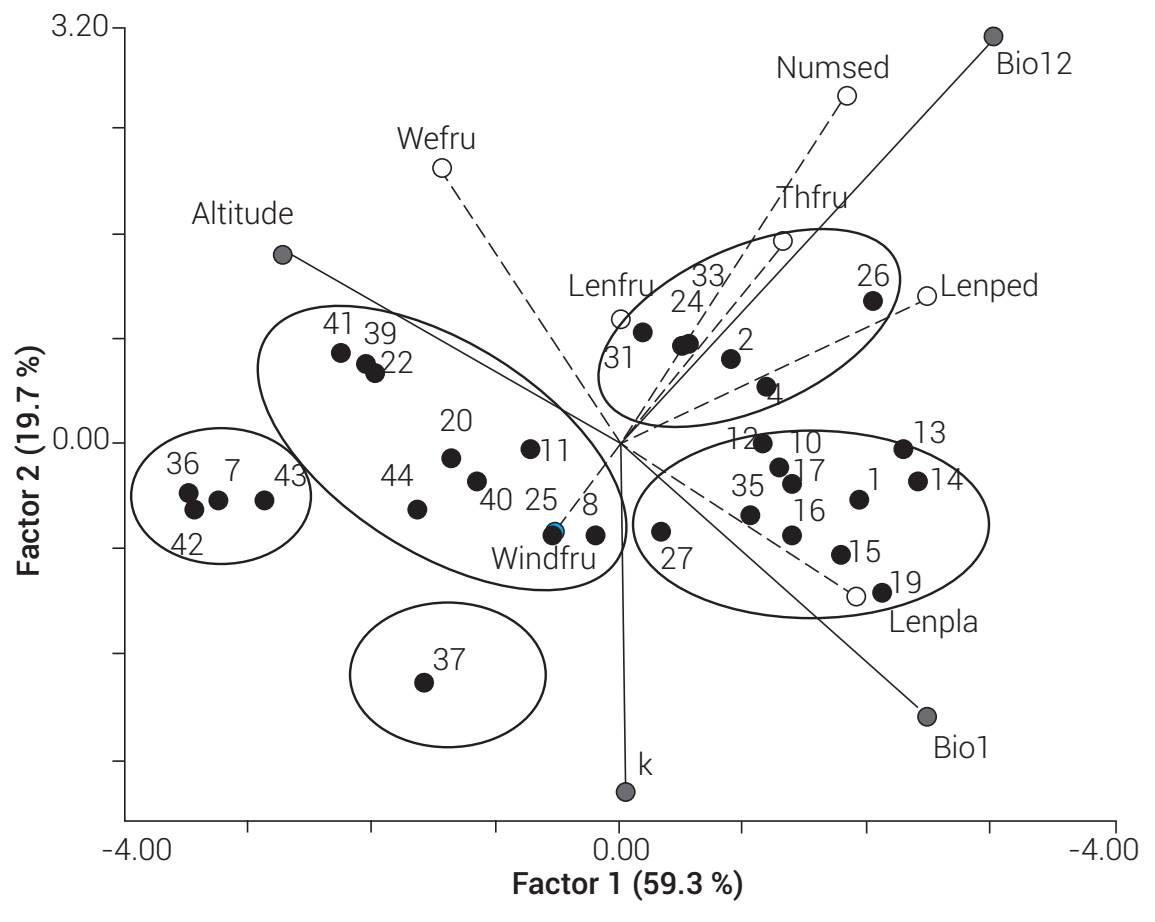

Partial least square regression in C. pubescens

The least square regression is a technique that generalizes and combines the principal component analysis and the linear regression analysis. It is ideal to predict a set of dependent variables (e.g. morphological) from a set of predictor variables (e.g. climatological). The covariable with the highest inertia and positively linked to the first axis was mean annual rainfall (Bio12), while negatively it was the availability of potassium (K) in the soil. The covariable positively linked to the second axis was altitude (DEM), while negatively was mean annual temperature (Bio1).

Accessions MEXUVCAL1, MEXUVCAL3, MEXUVTL2, MEXUVBV1, MEXUVCV5 and MEXUVTER3 showed the best values in number of seeds, fruit thickness and peduncle length; also, their expression is better in more humid environments (Figure 4). These accessions were collected in Calcahualco, Alpatlahuac, and Tepatlaxco, Veracruz, Mexico, whose altitude ranges from 1400 to 1800 masl and have a mean annual rainfall between 1800 and 2300 mm.

Figure 4 Interaction of 44 accessions of C. pubescens and four environmental variables, against a matrix of seven morphological variables of the fruit.

Meanwhile, accessions MEXUVCO1, MEXUVTEX1, MEXUVTZ1, MEXUVTLA2, MEXUVCO2, MEXUVCU2, MEXUVTZ2, MEXUVTEH1 and MEXUVDA1 were segregated, mainly due to the variables altitude (DEM) and potassium (K) as a soil property (Figure 4), they showed high values for fruit weight and width, which agrees with the locations of provenance, as Tehuipango and Alpatlahuac, Veracruz, Mexico, located at 2500 masl. The interactions detected in this dataset are mainly attributed to these two traits, from the ecological standpoint. This clarifies various ecological hypotheses that can contribute to better understand the relationships between environments and genotypes.

The presence of potassium (K) is closely linked to fruit weight, width and length, its presence is related to fruit quality. It is important to mention that the extraction of large amounts of this element is greatly due to the formation and development of fruits, which are the most demanding organ in Capsicum, with values from 70 to 80 % of the total amount extracted from each plant (Bugarín-Montoya et al., 2002).

The opposing projection of the covariables altitude (DEM) and mean annual temperature (Bio1) suggests that the latter changes differentially from one location to another, directly affecting some fruit characteristics. Accessions MEXUVBJ1, MEXUVTEP1, MEXUVTEN2 and MEXUVTET2 showed the lowest values in relation to the length of the placenta, which indicates that this characteristic was significantly affected by Bio1. According to the mean values of Bio1 registered in the locations where these accessions were collected, the values are above the optimum limits for C. pubescens (18 and 25 ºC). Pérez and Castro (2008) reported an optimum range from 15 to 22 ºC for proper development of C. pubescens; moreover, they mentioned that temperatures below 7 ºC halt the physiologicalmetabolic processes in the plant, while temperatures above 32 ºC during the critical stage of the crop stimulate abortion of flowers.

CONCLUSIONS

The distribution model MaxEnt produced probability values > 70 % for the presence of the species. These areas are located in the states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, Chihuahua and the Santa Martha Sierra in southern Veracruz; nevertheless, it is necessary to carry out exploratory trips to corroborate the presence of the species where it was predicted. Mean annual rainfall (Bio12), mean annual temperature (Bio1), potassium (K), and altitude (DEM) were the most importat bioclimatic variables to define specific environments for C. pubescens, and they significantly influence the expression of morphological characteristics of the fruit.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)