Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Frontera norte

versão On-line ISSN 2594-0260versão impressa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.35 México Jan./Dez. 2023 Epub 26-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2292

Article

Climate Migration and Militarized Borders: Human, Gender, and Environmental Security

1Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias-UNAM, México, uoswald@gmail.com

This article addresses Central American climate migration from a human, gender, and environmental (HUGE) security approach. It examines documents, government reports, press publications, international and national statistical data, and interviews to establish complex interrelationships between migration, disasters, poverty, pandemic, and survival dilemma. Militarized borders, pressure from the U.S. government, and transnational organized crime have increased the dangers and costs of undocumented migration. Could a U.S. immigration reform overcome this maelstrom of illegal migration and generate development in Northern Central America by sending remittances to their families? The article explores multiculturalism, ecosystem restoration, climate change adaptation, gender recognition, and a culture of care that would offer vulnerable people in Central America an alternative livelihood agenda in their country of origin.

Keywords: climate migration; human, gender, and environmental (HUGE) security; militarized borders; Northern Central America; United States

En este artículo se aborda la migración climática centroamericana desde un enfoque de seguridad humana, de género y ambiental (seguridad HUGE). Se examinan documentos, reportes gubernamentales, publicaciones de prensa, datos estadísticos internacionales y nacionales, así como entrevistas para establecer interrelaciones complejas entre migración, desastres, pobreza, pandemia y dilema de supervivencia. Las fronteras militarizadas, las presiones del gobierno estadounidense y el crimen organizado transnacional han incrementado los peligros y el costo de la migración indocumentada. ¿Pudiera una reforma migratoria en Estados Unidos superar esta vorágine de migración ilegal y generar desarrollo en el norte de Centroamérica por medio del envío de remesas a las familias que se quedan? El artículo explora la multiculturalidad, la restauración de ecosistemas, la adaptación al cambio climático, el reconocimiento de género y una cultura del cuidado que ofrecería a personas vulnerables de Centroamérica una agenda alternativa de vida en sus lugares de origen.

Palabras clave: migración climática; seguridad humana, de género y ambiental (seguridad HUGE); fronteras militarizadas; norte de Centroamérica; Estados Unidos

INTRODUCTION

Migration context in Central America

This article addresses climate migration from a human, gender and environmental security approach (Oswald-Spring, 2008, 2020a, 2020b), where climate disasters in Central America (Casillas, 2020; GFDRR, 2018), aggravated by poverty and the COVID-19 pandemic (Bollyky et al. 2021) have pushed entire communities into a survival dilemma (Oxfam Regional Humanitarian Team in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2020). Governments have implemented erratic health (CEPAL,2 2020), climate and security policies (Leutert, 2018) that have forced families to emigrate to the United States.

The government of former President Donald Trump pressured Mexico to detain migrants in its country through operations by the National Guard (Government of Mexico, 2019; WOLA, 2021). The National Institute of Migration (INM) issued limited permits to undocumented migrants and held them in makeshift camp sites on the Southern and Northern borders of Mexico (UNHCR, 2021). This structural violence affected the human rights of undocumented migrants and when organized crime took over migrant smuggling, violence and the costs of crossing into Mexico increased (Henao Castrillón & Hincapié García, 2019; Andrade, 2021; De la Rosa, 2021). The poverty generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and more severe disasters (OCHA, 2020) has forced Central American migrants to join caravans in the hope of collectively facing National Guard checkpoints and the multiple dangers along the way (Isacson, 2021).

The general objective of this article is to study from a HUGE security3 approach climate migration in Central America, associated with hurricanes and droughts (Zúñiga Arias et al., 2019), the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (CEPAL, 2021c), ancestral poverty (Banco Centroamericano de Integración Económica [BCIE], 2020) and public insecurity (Fundación Heinrich Böll México, Centroamérica y El Caribe, 2016).

The particular objectives are: a) to understand the complex interrelationship between climate disasters, pandemic (CEPAL, 2021c), intrafamily violence (Fuentes et al., 2022), public insecurity (USAID, 2017) and migratory dangers, where Central Americans defy risks on their way to the United States; b) analyze U.S. and Mexican immigration policies that have prioritized political-military security instead of HUGE security that focuses on vulnerable people and climate change (Moreno et al., 2020); and c) include the gender perspective (Jelin, 2021) to understand the differential risks between male and female migrants, where trafficking and sexual abuse (UNODC, 2020) directly affect female migrants.

Assumptions

U.S. and Mexican immigration policies based on the expanded and deepened HUGE security would facilitate authorized migration (Henao Castrillón & Hincapié García, 2019), would temporarily cover jobs in the United States due to the current workforce shortage, and would reduce violence related to organized crime.

Central America is highly exposed to climate risks (Zúñiga Arias et al., 2019). A HUGE security analysis would allow us to understand the complex interrelationship between climate disasters, pandemics, poverty, survival dilemma and public insecurity (Oswald, 2020a), where government adaptation (USAID, 2017) and resilience policies (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2017) could improve living conditions and limit the exodus of the population (Betancur, 2020).

Bottom-up local activities, through subsistence agriculture and microenterprises (Collin, 2021) with gender recognition (Fraser, 2008) would reduce violence in general and intra-family violence in particular (BM, 2021) by allowing the consolidation of living conditions in the place of origin (BCIE, 2020).

Article Organization

It starts from a broadened and deepened security that integrates human, gender and environmental security (HUGE security) (Buzan et al., 1998; Brauch et al., 2009; Oswald, 2008). The orientation of the object of reference changed from political-military security (territory and sovereignty) towards the well-being of human beings, against gender violence and in favor of environmental protection (Castañeda Carney et al., 2020; IPCC, 2022a). The values at risk are now survival, gender equality and sustainability. The threats have historically come from the patriarchal system that has based its power on wars, violence, discrimination and exploitation. These threats today are represented by transnational financial corporations and production companies (Díaz & Viales, 2020) that exploit labor and emit dangerous greenhouse gases (GHG) with which the physical-chemical conditions of the global atmosphere are altered (IPCC, 2021).

Subsequently, the analysis focuses on the Central American climatic disasters of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala (Casillas, 2020). Central American migration due to the impacts of climate change is reviewed from a gender perspective (Granada et al., 2021). Caravans are explored as a mechanism to improve the HUGE security of participants who escape from conditions of destruction and poverty, but who cannot pay for the transfer as undocumented migrants (Salazar, 2019). In transit through Mexico, the dangers of kidnapping and murder have increased (Andrade. 2021), exposing women and girls to trafficking and sexual abuse (UNODC, 2020).

On March 20, 2020, through the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), under the authority of former President D. Trump, for health reasons pertaining to COVID19, the immediate expulsion of undocumented immigrants to Mexican soil was imposed. This provision, called Title 42, made Mexico a “safe third country” (Cano, 2022). Faced with mass expulsions, the Mexican government exceeded its ability to provide humanitarian aid with dignity (UNHCR, 2021), forcing undocumented immigrants to survive in precarious conditions on the Northern border of Mexico. This unilateral policy has also increased transportation costs and the dangers that are basically in the hands of organized crime (De la Rosa, 2021). In the discussion the topic of climate migration is taken up again with a gender perspective (Llain & Hawkins, 2020) and the conclusions expose the contradiction between the demands of a recovering U.S. economy due to the loss of workforce resulting from deaths during COVID-19, and their persistent restrictive immigration policy.

CONCEPTUALIZATION OF HUGE SECURITY

Since the mid-19th century, the Central American bourgeoisie has shown an oligarchic management of finances based on its links with government corruption and transnational companies. This elite has enriched itself by paying low wages and exploiting natural resources, thanks to the fact that they have had the support of paramilitaries or criminals who protect their interests (Llorente, 2014; Yup, 2021). Throughout Central America, an internal colonialism that views the indigenous and the poor with contempt has predominated and allows the payment of low wages, thus increasing physical-structural violence (González, 2003). This bourgeoisie has consolidated its economy and political power with corruption, money laundering, capital flight and financial speculation in tax havens (UNODC, n.d.; Zapata Sagastume et al., 2016). Likewise, they have also enriched themselves with subsidies, trade barriers and corrupt privatizations that favored them (Llorente, 2014). Additionally, due to pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Central American countries were subjected to strict financial controls to pay their external debt service on time (Benmelech, 2020). With this international policy of the IMF and the economic policies imposed by the World Bank, debts among the poor have been socialized and profits privatized for this elite, where some have risen to world wealth (Oxfam Regional Humanitarian Team in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2020). This bourgeoisie has not reinvested its profits in the development of the country, nor has it stimulated jobs among its fellow citizens, even when inflation has pulverized the purchasing power of the poor (Díaz & Viales, 2020).

This model of capital accumulation between the bourgeoisie and transnational companies maintains inequality and exploitation in the Central American region (Prieto, 2021). Their misogynistic attitude includes exploitation and trafficking of women or girls, land grabbing, and collusion with government officials. These patriarchal practices also do not recognize the unpaid work of women caregivers. During the COVID-19 lockdown, domestic violence increased four times not only in Central America, but also in Mexico (Inegi, 2021), as well as femicides4. Inequality within a country is also measured with the Gini Index (World Bank [WB], 2016). Among the countries with a significant inequality index are Guatemala, with 48.3, El Salvador, with 40, and Honduras, with 50. This inequality is also reflected through the Human Development Index, whose values in the aforementioned countries are very low (96, 83, and 99, respectively) (BCIE, 2020, pp. 74-75).

These abysmal inequalities demand development changes that include women and young people who work in precarious conditions in the informal sector or who were recruited by organized crime (Leutert, 2018), given the lack of formal job opportunities. The figures for Northern Central America also show educational lags, and the privatization of healthcare services have fragmented medical care, which has increased mortality from COVID-19 (CEPAL, 2021c). A vicious circle has been generated between poverty and misery that limits schooling, and due to the lack of training, people get marginal jobs or suffer unemployment and violence, and in the face of disasters they opt for migration (BCIE, 2020). This poverty policy primarily affects women (CEPAL, 2020), young people and indigenous people (Garzón, 2020). The promotion of junk food has also increased obesity among the population (National Institute of Public Health [INSP], 2021) and has caused diabetes. Likewise, poverty and the loss of purchasing power have limited the consolidation of the internal market (CEPAL, 2022). Faced with these historical-structural problems, the article proposes a HUGE security, based on a care economy (CEPAL, 2021b), which will be discussed later.

Conceptualization of Security

Security refers, in the objective sense, to specific dangers (Brauch, 2005), to special dimensions (Oswald, 2020b), to objects of reference of international and national sovereignty, and to poverty, gender and indigenous conditions. It covers specific sectors such as energy, food, water, healthcare, and climate security. In the subjective sense, security involves the concerns of politicians, the media, scientists, and the public in the face of potential threats. To politically manage security, governments have securitized dangers by existential threats, while academics, by de-securitizing them, have prioritized a bottom-up vision within a cultural community (Wæver, 1995, 2011). Table 1 compares the traditional-Hobbesian vision of military-political security with a HUGE security that includes de-securitization processes, where the reference objects include vulnerable groups and ecosystems. The values at risk of HUGE security are survival, equality, and sustainability, while the sources of threat come from patriarchy, now transnational corporations, human consumerism, and the extractivism of natural resources.

Table 1. Military-National, Human, Gender, and Environmental Security

| DETERMINATION What security? |

REFERENCE OBJECT Security for who? |

VALUES AT RISK Security for what? |

THREAT SOURCES Security from whom or from what? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Military, National | The State | Sovereignty, territorial integrity |

Other States, State

crimes, guerrilla warfare, vertical power, organized crime, others |

| Human | Vulnerable groups, nations |

Survival, unity, and national identity |

Humanity, governments,

disasters, poverty, discrimination, crime |

| Gender | Women, children, elderly, minorities, disabled, unemployed, indigenous people |

Equality, equity,

identity, well-being, gender, and social relations, care, recognition |

Patriarchy, totalitarian, and

violent institutions (authoritarian governments, hierarchical religions, elites, beliefs, crime) |

| Environmental | Natural, urban, and rural ecosystems, biodiversity, natural resources |

Sustainability, life, environmental diversity, ecosystem services |

Nature, humanity, climate change, extractivism, Anthropocene |

Source: Oswald (2020b, p. 175).

Human Security

Human security (HS) proposed by the United Nations Development Program is centered on human beings (United Nations Development Program [UNDP], 1994). The values at risk are the survival of humanity, especially vulnerable groups. The dangers are corruption (Transparency International, 2021), poverty, crime, the survival dilemma, internal colonialism (González, 2003), transnational corporations and insatiable national bourgeoisies (Dal Pont, 2019). HS analyzes non-military threats against human beings, although the military-scientific-financial-corporate U.S. complex pressures Central America to arm itself and thus confront organized crime. Various levels of government and police are involved in these illegal activities, in addition to the national and transnational elite (Betancur, 2020).

The conceptualization of HS evolved with five pillars: first, the absence of fear (UNDP, 1994); second, the absence of needs and the care of vulnerable groups (UNDP, 2003); third, the absence of disasters (Birkmann, 2005) in the face of more severe climatic events, where vulnerabilities and socio-environmental risks were analyzed (Oswald Spring, 2014); fourth, when evaluating the Millennium Goals, Annan (2005) insisted on strengthening the Rule of Law with full respect for human rights; and fifth, live in a multicultural world with full right of minorities to their languages, customs and political practices (UNESCO, 2002). By integrating these five pillars, the HS analyzes threats, risks, difficulties and challenges that can be overcome through equality, cooperation and sustainability (Ibarra, 2019).

Gender Security

Oswald (2014) developed the concept of gender security (GS) taking up the four phases of feminism: epistemological, empirical, postmodern and point of view (Blazquez et al., 2010). Ecofeminism (Mies, 1998) linked natural exploitation with that of women, while social representations (Serrano, 2021), the gift economy (Vaughan, 1997) and multiple proposals from social movements supported the GS agenda. Both human and gender security start from a broadened and deepened security (Brauch et al., 2009) that includes women, children, indigenous people, the elderly, the disabled and LBGTQ+ (Fraser, 2008). This deepening guided the study of GS from the individual to the global.

The reference object of the GS includes vulnerable groups, where 70% of the poor are women (United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination [UNSCEB], 2020). Female oppression has devalued their work by receiving miserable wages and having precarious working conditions where care work is not paid and made invisible. In Mexico, 10.4% of women work without salary and only 39% are affiliated with the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS). Women perform four additional hours of free domestic work, which is equivalent to 1.7 billion MXN a year (Inegi, 2021). Reardon (1996) linked patriarchy to war, authoritarianism and violence, which for millennia has exploited humans and nature through slavery, colonialism, capitalism, and neoliberalism.

Gender recognition (Fraser, 2005) promotes socio-political, economic, and cultural equality. It delves into the direct and underlying relationships of power and violence. The values at risk are gender relations, equality, equity, and social representations (Serrano, 2021), while the threats come from patriarchal institutions such as authoritarian and corrupt governments, elites, transnational corporations and religions. Vaughan (2004) proposed overcoming discrimination with a gift economy, by highlighting the mother-newborn relationship. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL, 2021b) proposes empowering women through a care economy that consolidates economic, political, physical, and decision-making autonomy, where their sexual, reproductive, civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights would be guaranteed, thanks to a life free of violence and without discrimination.

Environmental Security and Climate Change

Climate change (Moreno et al., 2020) and human activities have devastated Earth. Environmental security (ES) not only analyzes the destruction of biodiversity (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [IPBES], 2018) and the financial costs of disasters (Zúñiga Arias et al., 2019), but also the impacts of four socially interrelated phenomena: depletion and contamination of water resources (Pahl et al., 2015); alteration of the physical-chemical composition of the air by GHG (IPCC, 2021); loss of natural fertility, salinization, deterioration, and erosion of soils (FAO, 2016); and eradication of biodiversity due to agricultural activities and accelerated urbanization (UNDESA, 2011). Population growth and chaotic urbanization in Central America have aggravated climatic disasters (Casillas, 2020). Russia-Ukraine and the United States are massive exporters of basic grains (GCMA, 2022), of which 82% are transgenic, which threatens native species of corn, beans, and potatoes. Mexico is one of the five mega-biodiverse countries (Conabio-UAEM, 2016) and the Latin American subcontinent contains 68% of all tropical forests and 40% of all plant and animal species in the world (Moreno et al., 2020), which are threatened by human activities.

Dalby et al. (2009) systematized the expansion of environmental security (ES) in four phases. The first was related to military contamination from wars and military activities (Westing, 2013), where weapons and chemicals (Agent Orange dropped massively over Vietnam) have caused mutagenicity among the native population and soldiers, as well as an increase in the ozone hole. The second phase was related to the destruction of natural resources, the loss of native and migrant species due to lack of care. In a third phase, multiple groups of transdisciplinary researchers analyzed climate forcing (IPCC, 2021), climate migration, lack of food, famines (FAO, 2018) and precarious survival (Escudero, 2016). The fourth phase explored conciliation mechanisms in the face of conflicts due to deteriorated and extracted environments, and climatic disasters.

Within the ES, the values at risk are sustainability, environmental diversity and life itself, while the threats come from human activities that cause climate change. Given the deteriorated natural processes, Crutzen (2002) proposed a new geological era, the Anthropocene, due to the alterations of the human being that are changing the history of the Earth. Moore (2016) criticized the neutrality of the concept and enunciated the Capitalocene, showing that transnational corporations are the most responsible for this massive destruction that is taking the planet toward its tipping point (Steffen et al., 2018).

By combining HS with GS and ES, Oswald (2020b) proposed a HUGE security that analyzes the links between the five human pillars, the four feminist approaches and the four environmental phases, as well as their complex, unpredictable and harmful interactions (Srigiri & Dombrowsky, 2022). When analyzing the outstanding participation of women in ecosystem recovery, ECLAC’s care economy (CEPAL, 2021b) emphasizes recognition, which consolidates the dignity, equality, and equity of women, girls, and indigenous people by empowering vulnerable sectors to overcome exploitation, violence and discrimination.

HUGE Security

The concept of HUGE security serves two functions: as a scientific analysis tool for complex problems and as an action guide for humanitarian actors responsible for eradicating poverty, managing disaster aid and assisting refugees (Laczko & Aghazarm, 2009). This HUGE security analyzes the links and interactions between the ecosphere and the anthroposphere, including climate change caused by anthropogenic GHG emissions (IPCC, 2021) that have altered the temperature of the land, sea, and precipitation. Forcing factors have caused climatic disasters (Moreno et al., 2020). The massive use of agrochemicals and deforestation have deteriorated soils and water (FAO, 2016). Changes in eating habits have increased the consumption of sugars and fat, while population growth and commercial agriculture have negatively reinforced these nature-human interactions. The dynamics of natural and agricultural systems have been altered, causing potential tipping points, some already irreversible, in the Earth system (Steffen et al., 2018).

The unpredictable mode of interaction between the ecosphere-anthroposphere is no longer linear and the impacts are exponential. These chaotic-abrupt processes affect populations, production processes and ecosystems. Their resilience is exceeded by complex events (UNISDR, 2015). Limited mitigation and insufficient adaptation have led to destruction and death. Oswald (2020a) argues that, in order to solve these multiple challenges, a broadened and deepened approach to security is necessary, capable of focusing security towards the Earth-human relationship. HUGE security implies epistemological shifts from the military-patriarchal perspective towards peace research, gender and environmental studies. By systematically analyzing socio-environmental phenomena, the methodological-isolationist approaches are limited and the complex interactions between HS, GS and ES are analyzed in a holistic, transdisciplinary, and transformative way. Poverty conditions have pushed millions of rural populations to settle in urban shantytowns in the Global South (UNDESA, 2011), where their consumption continues to deteriorate natural resources. Others have risked the road by migrating to foreign countries (Ortega & Morales, 2021).

Central American North

The climatic disasters in 2020 created a survival dilemma and have increased the number of Central American migrants. The IOM (2021, p. 1) reported that “what they all have in common is that they lost everything due to the hurricanes” and emigration increased after hurricanes Iota and Eta. Casillas (2020) insists that climate change poses risks to natural and human systems that increase food insecurity and cause displacement.

Yup (2021) analyzed Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras as a geographical-territorial unit, although Table 2 shows important socioeconomic differences. Guatemala has educational lags and multidimensional poverty, although a higher GDP/capita and a high gender gap. El Salvador is the smallest country, with a dominant urban population and lower annual GDP growth. Honduras, with a larger territorial extension, has a high gender gap and 59.6% of the population lives in multidimensional poverty (BCIE, 2020).

Table 2. Socioeconomic Indicators of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras

| Country | Population (millions) |

Area (km2) |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (MUSD) |

Annual GDP growth 2019 |

GDP/capita | Gender gap of 189 countries |

Urban popul. (%) |

Marginal urban popul. (%) |

Schooling (years) |

Multi- dimensional poverty (%) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guatemala | 17.5812 | 108 889 | 76 710.7 | 3.8 | 4 842.0 | 127 | 51.1 | 38.7 | 6.1 | 61.6 |

| El Salvador | 6 454 | 21 041 | 27 022.6 | 2.3 | 4 363.2 | 121 | 72 | 28.9 | 8.5 | 33.4 |

| Honduras | 9 746 | 112 492 | 25 025.4 | 2.7 | 4 187.2 | 133 | 57.1 | 27.5 | 7.2 | 59.6 |

Source: BCIE (2020, pp. 2, 4, 75).

This region contains between 7 and 10% of the world’s biodiversity (IPBES, 2018). The three countries have 218 municipalities and 25% of their population are young people between the ages of 15 and 35 (Clement et al., 2021). Vulnerable groups in risk areas were affected by severe hurricanes, floods (Vargas-Ulate, 2001), volcanic eruptions, earthquakes (Pérez-García, 2020), and droughts (Kuusipalo, 2017). In 2020, 28 hurricanes hit the region (Muñoz, 2020), of which Eta and Iota were especially destructive. When Iota reached category 5, with winds of 260 km/h (pressure of 917 mbar), there were no places left in the shelters. Limited government aid for prevention, fragile houses in exposed areas, and poor adaptation have exacerbated socio-environmental vulnerability (Oswald & Serrano, 2014). By losing everything, poverty increased. In the rural region of the Pacific, the drought (Miranda, 2021) has created a survival dilemma, forcing the population to emigrate. UNHCR (2021) estimated that in 2020, 867 800 people were displaced by climate disasters, lack of adaptation, and resilience (United Nations, 2020).

The destroyed homes, the lack of water, food and work, and poverty forced many families to emigrate to cities where insecurity has worsened their living conditions, despite government and international efforts (USAID, 2017). Chaotic urbanization has caused landslides (Moreno et al., 2020) and labor shortage or assaults have pushed multiple young people, children and families to emigrate (Zúñiga Arias et al., 2019). When crossing through Mexico, UNHCR (2021) indicated that asylum applications had increased from 3 400 in 2015 to 70 400 in 2019, fell 41% due to COVID-19 in 2020 and in 2021 increased 300%, reaching 123 187 asylum applications (INM, 2021), where 51% came from Honduras, 8% from El Salvador, and 5% from Guatemala, in addition to Haiti, Venezuela, and other countries.

ANALYSIS OF CENTRAL AMERICAN MIGRATIONS

Migrations with a Gender Perspective

Among the push factors that increase risks in Northern Central America, there is fragile governance (Ibarra, 2019), exacerbated by corruption and coercion by traffickers and transnational organized crime (Yup, 2021). Women and girls are especially vulnerable to exploitation, trafficking and victimization by sexual violence; sex is coerced to survive. Trafficking and sexual service (UNODC, 2020) are exchanged for shelter, food, protection or to pass immigration controls. The coercion of criminal traffickers has increased the risks for these migrants (Prieto, 2021).

Faced with the loss of quality of life and the lack of income due to COVID-19, massive layoffs, precarious working conditions, informality and severe disasters, many families did not have the money to feed themselves and even less to migrate. In addition, 28.1% of households in Honduras and 25.1% in Guatemala are headed by women, which has increased their precariousness (CEPAL, 2022). Despite health and socioeconomic changes among Central Americans, the region has changed fertility patterns. The average rate in Guatemala is three children per woman, for a larger percentage of indigenous population; in Honduras and El Salvador it is two children per woman (WB, 2022). Due to intrafamily violence, male infidelity, poverty and public insecurity, there have been breakups in couples, single women have had to develop multiple survival strategies, such as creating extended homes beyond consanguinity relations. They also exercise sisterhood among female households, live on the land of the employer and take care of houses or the elderly in exchange for housing and food for themselves and their children (UCA, 2016). Women in Central America have joined the precarious job market or informal trade. The pandemic acted as an additional break in these activities and affected the social fabric. Children and single women have migrated to the United States struck by extreme poverty. Given their lack of money, the dangers and the costs of the transfer, they have joined the caravans.

Central American Caravans

The caravans began with mothers looking for their missing children in Mexico. De la Rosa (2021) indicated that they are transnational justice processes in regions with high levels of violence. Sassen (2021) shows that these caravans and migration have influenced the global regulation of unequal labor markets, where the difference in wages represents a pull factor to emigrate. In addition, investments in the public administration of the president of the United States, Joe Biden, are also pull factors, while impoverishment, discrimination, violence, and unemployment in Central America (Betancur, 2020) have generated pressure for expulsion. Another factor that attracts migration is the difference in wages between the United States, Mexico and Central America. In 2021, the U.S. minimum wage increased from 7.25 to 15 USD per hour and in the Free Zone of the Northern Border of Mexico, it increased to 260.34 MXN (12.70 USD) for 8 hours of work and to 172.87 MXN (8.43 USD) in the rest from the country. Although Mexican purchasing power parity is 9.5 higher relative to the purchasing power of the dollar, wages in the United States have become a powerful draw (Clement et al., 2021). This was reflected by the remittance flows in 2021, which reached 51 600 000 million dollars (MUSD) to Mexico, only surpassed by remittances sent by migrants to India. They include remittances that were sent to expelled Central American migrants living on the Mexican border (Banco de México, 2022) and have become a financial line for survival. In 2021, remittances in Guatemala amounted to 15 295 000 MUSD, in Honduras to 6 484 000 MUSD and in El Salvador to 5 066 000 billion USD, which represents the greatest foreign investment that reaches the poorest regions with indigenous populations, which has become another pull factor for undocumented migration (Balcáceres, 2022; Banco Central de Reserva de El Salvador, 2022).

In January 2021, when the administration of former President Trump changed to that of Joe Biden, false offers in the media reported the existence of jobs at the U.S. border. In addition, the use of cell phones has changed migratory mobility; people can find out where to cross the borders, where to find a smuggler, how easy it is to get around, find shelters, and find out about government repressions during crossings through Guatemala, Mexico, and the U.S. There are reports about the deportations, forced returns, and the dangers of transnational crime involved in transporting undocumented immigrants to the United States and about the accidents along the way.

In Mexico, shelters, non-governmental support for health, food and social protection emerged that are related to the reproductive economy. They reduce dangers from organized crime and allow migrants to rest in a safe place. However, criminals also use these communication networks to commit hiring scams, kidnapping, extortion, trafficking and other activities that have increased risks among passers-by.

Social mobility was configured not only as a response to poverty, conflicts and socio-environmental risks, but also showed new forms of agency that required audacity. The changes that have occurred also indicate changes in the Central American political subjectivity, whose public expression was the appointment of Xiomara Castro as president of Honduras, who is sensitive to the social demands of the impoverished majorities.

Faced with multiple challenges, in Honduras 4 500 desperate people joined a caravan in November 2021 to overcome the threats on the migratory path. Among them were trapped migrants (Dowd, 2008), people who, due to lack of money, could not leave their place of origin. A single 16-year-old woman with a young child commented: “This caravan represents a hope to escape our misery. There are numerous women, families with small children, single children and people with disabilities in our caravan. They cannot travel alone because of the threats from the authorities and criminals” (personal communication, December 4, 2021). This caravan has promoted gender recognition (Fraser, 1998) and the empowerment of women. Greater female participation in this caravan has reduced the number of deaths along the way and youth human trafficking. By emphasizing GS, it was possible to overcome the gender paradox (Lorber, 1994) expressed in the form of discrimination and exploitation. The caravan has generated conditions of greater equality, where women have become active agents, capable of overcoming difficulties in long walks: foot blisters, dehydration and caring for minors.

In addition, the caravans have generated a care economy, where vulnerable groups have found the possibility of drawing the attention of the mass media in the face of insecurity and the pain caused by disappearances. They have exposed government corruption in their countries of origin and their alliances with transnational crime. The capacity of women to overcome their precarious socioeconomic conditions, discrimination and violence in their abandoned home has been stimulated (CEPAL, 2021a). Women empowerment has not only been consolidated along the way but was maintained when they were repatriated. In their country of origin, they began the fight for greater equality and recognition of their work. During their journey, they exhibited on video the inhumane policies by the military closures at the borders (Sassen, 2021) and these migrants have questioned the expulsions from the United States to safe third countries, that is, to Mexico (HRW, 2020). Thus, this and subsequent caravans have generated socially responsible mobility strategies in conditions of high vulnerability, showing the truncated development processes in Central American countries due to U.S. policies and their transnational businesses of exploitation, where authoritarian and corrupt government models have aggravated misery (Terminiello, 2014).

Militarized Borders in Mexico and the U.S.

The United States requires workers to cover jobs due to deaths from COVID-19 (more than 5 million), but also for new infrastructure work by the Biden government (The Economist, 2022). Under U.S. pressure, Mexico deployed 25 000 National Guard members on both borders. In 2019, they detained 81 000 immigrants in the south and expelled 62 000 people to their countries of origin (Ruiz, 2020). The UNHCR asked Mexico in March 2020 to support children, adolescents and women who had entered the country alone and Mexico that same year granted 41 329 asylum petitions, and in November 2021 another 108 195 permits were granted to Central Americans to legally stay in the country (INM, 2021). The International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2021) estimates that by 2050 there could be 17 million climate refugees from Latin America alone, seeking better living conditions in the United States. The World Bank (Clement et al., 2021) estimates that in 2050 there could be up to 216 million internal migrants for climatic reasons.

In addition, the Northern border is highly conflictive due to the presence of organized crime groups that fight for drug trafficking control; according to Red Mesa de Mujeres, in 2021 only in Ciudad Juárez 171 murdered women were reported (Tovar, 2022). Living on this border forced women to self-organize, since the government could not guarantee security and decent living conditions to those expelled.

The Border Patrol (2022) reported that, between October 2020 and September 2021, around 1.735 million asylum seekers were expelled to Mexico. In October 2021, U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar insisted that both countries (the United States and Mexico) have committed to returning undocumented migrants to their countries and Mexico has returned expelled migrants on special flights to Northern Central America. The National Guard and the National Migration Institute (INM) have limited transit through Mexico with dissuasive actions, confronting migratory groups coming from Latin America, Asia and Africa. In addition, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance registered 62 804 Haitian asylum seekers in 2021, including their dependents, mostly Brazilian and Chilean nationals (United Nations, 2022b), but thousands of new applicants are arriving.

Returning to the HUGE security proposal, we can see that caravans and women’s self-organization, based on gender recognition and empowerment, have reduced fear among Central American migrants who travel in caravans and have been forced to leave their homes of origin due to disasters and for their basic survival needs. In the transit of migrant caravans through Mexico, local NGOs have improved in terms of respect for human rights, so that, thanks to the long-stay permits granted, women with children have found means of survival and have limited the violence from authorities on both sides of the border. But transnational crime continues to threaten and extract money from this precarious population. Although the self-organization of migrants has improved protection and exposed the dangers to the press, it has not been able to prevent them.

Another difficulty was the policy of Title 42, imposed by the administration of former President Donald Trump (Ruiz, 2020) in 2019, which threatened Mexico with taxing their exports if they did not accept the expellees into their territory. During 2020, Mexico received 61 000 expelled migrants from the United States in precarious conditions, who were waiting for their refugee applications to be accepted (INM, 2021). These pressures continued through the federal judges during the Joe Biden administration, who implemented policies to immediately expel two-thirds of the 1.66 million undocumented immigrants arriving in 2021 (Bolter, 2021).

This border region also generates opportunities and migrants cross several times into the U.S. with the risk of being immediately expelled; others find work in Mexico. Especially families and mothers with children seek alternatives to enter the United States and cross in groups through the Arizona desert, putting their lives at risk in the face of extreme weather and venomous snakes.

Light and Miller (2018) investigated whether undocumented migration increased violent crime and concluded that violence comes from smugglers, human traffickers, drug traffickers, and law enforcement. They generate violence and migrants are their victims. Human trafficking includes kidnapping, extortion, trafficking, robbery, assault, sexual abuse, and abandonment. These crimes occur on train tracks, in trucks, cars, at bus stations, on highways, country roads, highways, private residences, and vacant lots. The local or national police are unable to control these criminal organizations due to corruption or direct involvement, and by allowing crime to act show their lack of governability (Red de Documentación de las Organizaciones de Defensa del Migrante [Redodem], 2020). Even local actors collaborate with criminal groups and charge money to cross or force migrants into drug trafficking and other illegal activities (Leutert, 2018).

DISCUSSION

Migration in Times of Climate Change

Four decades ago, it was mostly undocumented men who immigrated to the United States. Starting in the year 2000, the number of women crossing the border in search of employment in the service sector increased. Since September 11, 2001, U.S. security policies have justified the implementation of drastic measures to control the entry of immigrants. As a result, bureaucracy has increased and it has been promoted that people be linked to transnational crime, and thus have undermined their own national security. Legal changes and the wall built during the administration of former President Trump have strengthened border controls. For national security, this former president reinforced the Border Patrol, increased deportations and has separated families, banishing unaccompanied children thousands of kilometers away in Mexico from where their parents were expelled. The Biden government tried to reverse this inhumane policy, but Title 42 forces migrants to wait in Mexico for asylum authorization, facing insecurities in this border region for months. To avoid these dangers, new immigration rules for Venezuelan refugees have worked and their undocumented immigration has been substantially reduced. The U.S. authorities require that people must apply for their visa in the country of origin, arrive by plane and meet other requirements to obtain authorized entry.

The United States also does not distinguish between climate refugees and others, but on the U.S.-Mexico border 200 000 people were detained in July 2021 (IOM, 2021). Among these detainees, 45% were from Central America; 29% Mexican and 26% came from other countries. “In May 2019, (…) people traveling as a family fell from 64 to 38%. The proportion of (…) unaccompanied minors remained unchanged at 9%” (Gramlich, 2021, n.p.). Due to the involvement of transnational crime, there have also been forced disappearances of migrants throughout Mexico (United Nations, 2022a). Since 2006, Carrasco (2013) reported the emergence of high caliber weapons among kidnappers, legal permits from the Mexican National Institute of Migration, and an ease to cross military checkpoints or immigration posts, all of which indicate collusion with authorities and police. On April 6, 2011, 193 migrants were found in clandestine graves in the municipality of San Fernando, Tamaulipas, executed by the Los Zetas cartel, which shook public opinion. The Mexican legal obligation to guarantee the safety of migrants has not been complied with.

New attacks continue to occur during the journey and the Organizations of Migrant Defense Documentation Network (Redodem, 2020) shows that government facilities for refugees are deficient and that they are in highly precarious conditions. This organization insists that human rights are violated and that undocumented migration generates risks, violence, and violations due to the National Guard checkpoints along the migratory routes. The Redodem demands to eliminate immigration detention and offer HUGE security during transfer and decent conditions for all undocumented migrants who cannot enter the U.S. or return to their country of origin. The precarious conditions in these refugee camps on both borders led to outbreaks, conflicts and violence. Padilla Pérez et al. (2020) further acknowledge that the U.S. diaspora is supporting the transfer of their undocumented family members by paying the trafficker only when they have safely arrived in the United States.

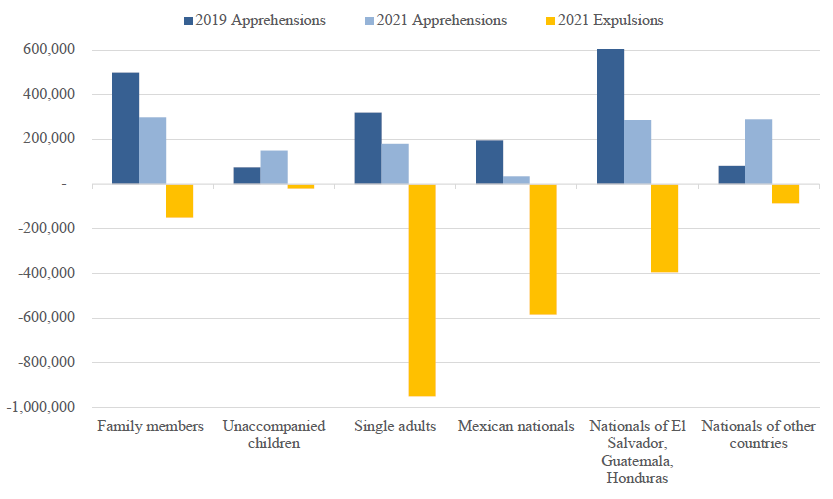

As previously stated, high unemployment rates and the lack of opportunities and informal work have pulverized income throughout Central America, which is why the migratory flow has increased, and its composition has recently changed. These changes respond to the complexity of migration since in 2019 and 2020 there were more family and Central American nationality immigrations (graph 1), most of which were apprehended and expelled. While in 2020 Mexican migration increased due to the pandemic and the consequent unemployment. Most of the detained adults were immediately repatriated, while the unaccompanied children were housed in U.S. camps.

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Border Patrol (2022).

Graph 1. Detentions and expulsions of undocumented immigrants on the South-West border, 2019-2021

Inhuman detention conditions on the U.S.-Mexico border have not limited the flow of undocumented immigrants. Despite the lack of hygiene and the overcrowded conditions in cages, migrant caravans continue to arrive in the United States. The Biden administration has vaccinated these migrants to also protect the local population and immigration officials. It has also provided vaccines to the Mexican government to immunize the entire population in the border region, including expelled refugees. The economic reasons given were to protect those who work in the maquila sector, a rapid opening of the border to stimulate trade and expedite the transport of export and import merchandise between the two countries.

The Central American region is considered the most violent in the world without having a war. According to the World Bank, El Salvador ranks first, with 62 homicides, Honduras 42 (5th), Mexico 29 (14th) and Guatemala 26 homicides (16th) per 100 000 inhabitants (BM, 2021). This violence has multiple causes: transnational organized crime, poverty, intra-family conflicts, gender violence, femicide, drug cultivation, exploitation of the workforce, extortion, discrimination, migration, as well as the trafficking of people, drugs, human organs, archaeological pieces and exotic plants or animals.

Another problem related to undocumented migration in Central America is human trafficking. After the economic recession and disasters (2019-2020), victims have become a local target (UNODC, 2020) and 79% of those taken for trafficking are girls and women, where girls represent a third of the detected victims; while 91% of these trafficked women are sent to the United States and 81% are exploited for sexual purposes. Over the last five years, ECLAC (CEPAL, 2021c) has detected a 40% increase in girls among the victims as a result of disasters, pandemic and the economic crisis. The militarization of the southern and Northern borders with members of the National Guard from different regions of Mexico has also increased prostitution. Faced with increasing National Guard-INM checkpoints along the way, the migratory vortex has shifted from the American dream to a stable job in Mexico, especially in regions where new mega-projects are being built (Camargo & Prieto, 2021). These migrants have applied for humanitarian visas and work permits in Mexico.

Thus, the Central American migratory history reflects complex factors: people fleeing climatic disasters, extreme poverty, land grabbing, lack of government support, violence, extortion, threats from transnational crime that seek to recruit their children. The expulsion factors in migration are interconnected with adverse conditions, where social, economic, family, climatic and cultural aspects interact and negatively reinforce the lives of women and girls. The caravans were made up of disabled people, women and children who were exposed to situations of violence in their homeland, which encouraged them to walk hundreds of kilometers despite dehydration and repression by the National Guard-INM, hoping to achieve decent living conditions and futures for their children.

The increasing militarization along the way, inhumane policies against migrants, and political pressure from local inhabitants have induced the governments of the United States and Mexico to return to military-political security by increasing repression against these migrants (Prieto, 2021). However, climatic disasters and loss of survival will continue to increase the number of migrants.

CONCLUSIONS

This article explored undocumented climate migration from Central America from a human, gender and environmental security perspective, where deteriorating environmental conditions (GFDRR, 2018) and the COVID-19 pandemic have pushed families into a survival dilemma, violence and intrafamily conflicts. Faced with erratic health, climate and security policies, the Central American exodus has increased and undocumented migrants have faced militarized borders and repression. U.S. and Mexican immigration policies have not placed the vulnerable population or environmental recovery at the center. Nor have they understood the complex interrelationship between climate disasters, pandemics, domestic violence, and organized crime (USAID, 2017), where despite the dangers, migrants seek to find a better life in other countries.

In terms of human security, an orderly migration would solve the lack of work force in the U.S. and would allow remittances to be sent to those left behind in Central America, which would allow a win-win situation for all involved. In gender security, migration and caravans have recognized and empowered women and girls. The transportation costs of illegal trafficking networks have increased and they have become a lucrative business of more than 14 billion USD per year in the hands of transnational organized crime (García, 2021).5

Discrimination against women and girls exists throughout the region.

Androcentric value patterns also pervade popular culture and everyday interaction. As a result, women suffer gender-specific forms of status subordination, including sexual harassment, sexual assault, and domestic violence; trivializing, objectifying, and demeaning stereotypical depictions in the media; disparagement in everyday life; exclusion or marginalization in public spheres and deliberative bodies; and denial of the full rights and equal protections of citizenship. These harms are injustices of misrecognition. They are relatively independent of political economy and are not merely “superstructural” (Fraser, 1998, p. 2).

Therefore, the alternative recognition of gender security, within the framework of HUGE security, requires additional policies for each woman and girl, but also new masculinities among men (Chiodi, 2019). It demands a policy of equality in wages and working conditions, as well as the recognition of parity in political and social participation. A crucial factor is the care economy with empowerment (CEPAL, 2021b) and overcoming the historical devaluation of feminine culture that simultaneously allows economic, social and political equality.

Starting from a HUGE security approach with a gender perspective and knowing that the majority of human beings are exposed to female and male discrimination, it is urgent to overcome this internal colonialism (González, 2003) by providing comprehensive security, where there is an integrated recognition of women and men. Environmental security tightens the care of nature, humanity (Niva, 2022) and adaptation conditions. A life without violence in a healthy environment was the proposal of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (United Nations, 2015), the 2030 Agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2018) and national agendas throughout Central America. A comprehensive approach reinforces the empowerment of vulnerable people, prevents patriarchal cultural discrimination, violence and promotes a culture of recognition, an economy of peace and care (Collin, 2021).

The experiences during the migratory journey have empowered women. Although repatriated to their place of origin, they continue to promote human rights and gender equity policies in relation to wages and unpaid domestic work. Table 2 showed that El Salvador, despite having the highest rate of violence, has more favorable socioeconomic and educational conditions to overcome emerging obstacles and migration.

The increase in disasters related to climate change, which means the loss of homes, the scarcity of food, water, and fertile soils (Toscano, 2017), makes it necessary to promote government policies (USAID, 2017) on environmental security and to take adaptation and resilience actions in these regions highly exposed to climate events (Zúñiga Arias et al., 2019). Deforestation, open-pit mining, the lack of recovery of ecosystems, the lack of water and healthy food, the frequent small disasters, but also the presence of destructive hurricanes and droughts along the Pacific (Moreno et al., 2020) have increased the environmental insecurity of Central Americans. The ECLAC (CEPAL, 2022) found that climatic impacts on agricultural production are decisive, especially when it comes to subsistence crops that are managed mainly by women in orchards and family farmyards (IPCC, 2022b). Extreme weather events have destroyed this type of livelihood (Oswald & Serrano, 2014) and have increased hunger, intra-family violence, and health problems in families (Bradshaw & Linneker, 2009).

The political framework of a HUGE security guides migrants and vulnerable people in Central America towards the possibilities of a programmatic agenda with coherent alternatives, without people having to leave their homes. It reduces the vortex associated with undocumented migration, integrates gender recognition and promotes bottom-up processes with empowerment in the communities. If it is reinforced by a policy of equal wages, decent working conditions and political participation, it can trigger the recognition of the feminine part in men and women (Reardon & Snauwaert, 2015). By adding a multicultural vision (Arizpe, 2015) with sustainable ecosystem care (IPBES, 2018), HUGE security is anchored throughout the region and climate disasters can be mitigated.

In short, a HUGE security with gender recognition (Fraser, 2008), care economy for all and environmental recovery would help reduce undocumented migration, improve local conditions, mitigate the impacts of climate disasters and create conditions of well-being and quality of life for all Central Americans. The challenge is complex, but the pain, dangers and deaths are worth avoiding in undertaking this effort towards HUGE security.

REFERENCES

Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados (ACNUR). (13 de abril de 2021). Solicitudes de asilo en México baten su récord en marzo. Noticias ONU.https://news.un.org/es/story/2021/04/1490802 [ Links ]

Andrade, Aarón (enero, 2021). ¿Cómo se construye el terror socialnarco-estatal en México? (2010-2014). Revista Latinoamericana, Estudios de la Paz y el Conflicto, 2(3), 114-130. https://doi.org/10.5377/rlpc.v2i3.10443 [ Links ]

Annan, K. (2005). In larger freedom. UNGA. [ Links ]

Arizpe, L. (2015). Vivir para crear historia. Antología de estudios sobre desarrollo, migración, género e indígenas. Migue Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Balcáceres, P. (1 de noviembre de 2022). Las remesas en Centroamérica van por su segundo mejor año de la década. Blomberg Línea. https://www.bloomberglinea.com/2022/11/01/las-remesas-en-centroamerica-var-por-su-segundo-mejor-ano-de-la-decada/ [ Links ]

Banco Central de Reserva de El Salvador. (21 de enero de 2022). El Salvador recibió US$7,517.1 millones en remesas familiares durante 2021. Noticias BCR. https://www.bcr.gob.sv/2022/01/21/el-salvador-recibio-us7517-1-millones-en-remesas-familiares-durante-2021/ [ Links ]

Banco Centroamericano de Integración Económica (BCIE). (2020). Centroamérica en cifras. https://www.bcie.org/fileadmin/bcie/espanol/archivos/novedades/publicaciones/informe_de_coyuntura/Report_Central_America_in_Figures.pdf [ Links ]

Banco de México. (2022). Ingresos y egresos por remesas, diciembre de 2021 [Reporte analítico]. Autor. https://www.banxico.org.mx/publicaciones-y-prensa/remesas/%7BB4F97FD6-A4A1-E287-392D-385EF3FB39BD%7D.pdf [ Links ]

Banco Mundial (BM). (2021). Homicidios intencionales (por cada 100.000 habitantes) [Base de datos]. Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito. https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/VC.IHR.PSRC.P5 [ Links ]

Benmelech, E. (19 de agosto de 2020). How credit ratings are shaping governments’ responses to Covid-19? Forbes Media. https://www.forbes.com/sites/effibenmelech/2020/08/19/how-credit-ratings-are-shaping-government-responses-to-covid-19/?sh=7fa462051d01 [ Links ]

Betancur, A. (2020). De la geopolítica clásica a la geopolítica crítica: perspectivas de análisis para fenómenos del espacio y el poder en América Latina, FORUM. Revista Departamento Ciencia Política, 17, 126-149. [ Links ]

Birkmann, J. (2005). Danger need not spell disaster. But how vulnerable are we? United Nations University Press. [ Links ]

Blazquez, N., Flores, F. y Ríos, M. (2010). Investigación feminista: epistemología, metodología y representaciones sociales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Bollyky, T. J., Murray, C. J. L., Reiner Jr., R. C. (2021). Epidemiology, not geopolitics, should guide COVID-19 vaccine donations. The Lancet, 398(10295), 97-99. [ Links ]

Bolter, J. (Octubre de 2021). It is too simple to call 2021 a record year for migration at the U.S.- Mexico Border. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/2021-migration-us-mexico-border [ Links ]

Border Patrol (2022). CBP Releases Operational Fiscal Year 2021 Statistics. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-operational-fiscal-year-2021-statistics [ Links ]

Bradshaw, S. y Linneker, B. (2009). Gender perspectives on disaster reconstruction in Nicaragua: reconstructing roles and relations? En E. Enarson y P. Chakrabarti (Eds.). Women, gender and disaster: global issues and initiatives (pp. 75-88). Sage. [ Links ]

Brauch, H. (2005). Environment and human security: towards Towards freedom from hazard impacts. UNU-EHS. [ Links ]

Brauch, H. G., Oswald Spring, Ú., Grin, J., Mesjasz, C., KameríKameri-Mbote, P., Chadha Behera, N., Chourou, B. y Krummenacher, H. (Eds.). (2009). Facing global environmental change. Environmental, human, energy, food, health and water security concepts (HSHES, Vol. 4). Springer. [ Links ]

Buzan, B., Waever, O. y De Wilde, J. (1998). Security. A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

Camargo, A. y Prieto, S. (2021). Borders of the Southern Border. Between territorial (re)organization and human (re)distribution. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Cano, M. (30 de abril de 2022). ¿Fin del Título 42? Llamada entre Biden y AMLO tuvo a la migración como protagonista. France 24. https://www.france24.com/es/ee-uu-y-canad%C3%A1/20220430-estados-unidos-m%C3%A9xico-migraci%C3%B3n-frontera-t%C3%ADtulo-42-elecciones [ Links ]

Carrasco, G. (2013). La migración centroamericana y su paso por México. Alegatos, 83, 170-194. [ Links ]

Casillas, R. (2020). Migración internacional y cambio climático: conexiones y desconexiones entre México y Centroamérica, URVIO. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad (26), 73-92. https://doi.org/10.17141/urvio.26.2020.4038 [ Links ]

Castañeda Carney, I., Sabater, L., Owren, C., Boyer, A. E. y Wen, J. (2020). Gender-based violence and environment linkages: The violence of inequality. IUCN. [ Links ]

Chiodi, A. (2019). Varones y masculinidades. Instituto de Masculinidades. [ Links ]

Clement, V., Rigaud, K. K., De Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Adamo, S., Schewe, J., Sadiq, N. y Shabahat, E. (2021). Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. Part II [Informe]. World Bank. [ Links ]

Collin, L. (2021). Economía local y diversa, una opción resiliente, sustentable de trabajo digno. En U. Oswald-Spring, M. del R. Hernández Pozo y M. Velázquez Gutiérrez (Eds.). Transformando al mundo y a México: Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 2030: justicia, bienestar, igualdad y paz con perspectiva de género (pp. 117-140). CRIM-UNAM. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2020). Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina–Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible. Autor. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2021a). La autonomía económica de las mujeres en la recuperación sostenible y con igualdad. Autor. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2021b). Economía del cuidado. Autor. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2021c). El impacto social de la pandemia en América Latina. Autor. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2022). Cepalstat: Bases de datos y publicaciones estadísticas [Base de datos]. Naciones Unidas. https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/index.html?lang=es [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio) y Universidad Autónoma de Morelos (UAEM). (2006). La diversidad biológica en Morelos. Autor. [ Links ]

Crutzen, P. J. (2002). Geology of mankind. Nature, 415(23). https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a [ Links ]

Dal Pont, S. (2019). El rol del capital financiero en los intercambios con el exterior. Apuntes Agroeconómicos, 13(19), 1-4. https://www.agro.uba.ar/apuntes/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/el-rol-del-capital-financiero-en-los-intercambios-con-el-exterior-dal-pont.pdf [ Links ]

Dalby, S., Brauch, H. G. y Oswald Spring, Ú. (2009). Environmental security concepts revisited during the first three phases (1983-2006). En H. G. Brauch, U. Oswald Spring, J. Grin, C. Mesjasz, P. Kameri-Mbote, N. C. Behera, B. Chourou y H. Krummenacher (Eds.). Facing global environmental change: Environmental, human, energy, food, health and water security concepts (HSHES, vol. 4). (pp. 781-790). Springer. [ Links ]

De la Rosa, P. (2021). Violencia contra migrantes: escenario común tras la guerra contra el crimen organizado en México. Revista del Instituto de Ciencias Jurídicas, 15(47), 210-232. [ Links ]

Díaz, D. y Viales, R. (2020). Centroamérica: neoliberalismo y COVID-19. Geopolítica(s) Revista de Estudios sobre Espacio y Poder, 11. https://doi.org/10.5209/geop.69017 [ Links ]

Dowd, R. (2008). Trapped in transit: The plight and human rights of stranded migrants. United Nations. [ Links ]

Equipo Regional Humanitario de Oxfam en América Latina y el Caribe (2020). “Aquí lo que hay es hambre”. Hambre y pandemia en Centroamérica y Venezuela. Oxfam. [ Links ]

Escudero, J. (2016). Estrategias de supervivencia y adaptación. Red Sociales, Revista del Departamento de Ciencias Sociales. 4(1), 04-06. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2016). Status of world’s soil resources. Autor. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2018). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Autor. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. (1998). Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, participation (Discussion Paper FS I 98-108). Wissenschaftszentrum für Sozialforschung. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. (2005). Reframing justice in a globalizing world. New Left Review, 36, 1-19. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. (2008). Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. En G. L. Henderson y M. Waterstone (Eds.), Geographic thought: A praxis perspective (pp. 72-89). Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M., Hernández, C. y Alcay, S. (2022). Situaciones de vulnerabilidad en personas en movilidad y personas locales frente a la trata de personas en el municipio de Tapachula en el contexto las caravanas migrantes 2018-2019. Frontera Norte, 34(4), 2-22. https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2191 [ Links ]

Fundación Heinrich Böll México, Centroamérica y El Caribe (Ed.). (2016). Re-conceptualización de la violencia en el Triángulo Norte. Abordaje de la seguridad en los países del norte de Centroamérica desde una visión democrática. Autor. [ Links ]

García, J. (22 de diciembre de 2021). México reconoce que las redes de tráfico de personas se independizaron de los cárteles del narcotráfico. El País. https://elpais.com/mexico/2021-12-23/mexico-reconoce-que-las-redes-de-trafico-de-personas-se-independizaron-de-los-carteles-del-narcotrafico.html [ Links ]

Garzón, M. (14 de mayo de 2020). América Latina: Más de 28 millones de personas entrarían en situación de pobreza este año por el COVID-19. BBVA. https://www.bbva.com/es/sostenibilidad/america-latina-mas-de-28-millones-de-personas-entrarian-en-situacion-de-pobreza-este-ano-por-el-covid-19/ [ Links ]

Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). (2018). Gender equality and women’s empowerment in disaster recovery. GFDRR/World Bank. [ Links ]

Gobierno de México (2019). Declaración conjunta. Autor. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/467956/Declaracio_n_Conjunta_Me_xico_Estados_Unidos.pdf [ Links ]

González, P. (2003). Colonialismo interno. (Una redefinición). UNAM. [ Links ]

Gramlich, J. (13 de agosto de 2021). Migrant encounters at U.S.-Mexico border are at a 21-year high. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/13/migrant-encounters-at-u-s-mexico-border-are-at-a-21-year-high/ [ Links ]

Granada, I., Ortiz, P. Muñoz, F., Saldarriaga Jiménez, A., Pombo, C. y Tamayo, L. (2021). La migración desde una perspectiva de género: ideas operativas para su integración en proyectos de desarrollo. BID. [ Links ]

Grupo Consultor de Mercados Agrícolas (GCMA). (2022). Tendencia Bolsa de Chicago, 25 de enero de 2022. GCMA. [ Links ]

Henao Castrillón, K. J. e Hincapié García, A. (2019). Migrantes centroamericanos en tránsito por México ¿Primacía de los Derechos Humanos o de los capitales? Agora USB, 19(1), 231-243. https://doi.org/10.21500/16578031.4128 [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2020). World Report 2020. Autor. [ Links ]

Ibarra, R. (2019). Cambio climático y gobernanza. Una visión transdisciplinaria. IIJ-UNAM. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi) (2021). Estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de la eliminación de la violencia contra la mujer (25 de noviembre) (Comunicado de prensa, núm. 689/21). Inegi. https://upes.edu.mx/radio/?p=5249 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres (Inmujeres). (2022). El Inmujeres en 2021 . Autor. http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/documentos_download/INMUJERES_EN_2021_F.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM) (2021). Tema Migratorio 130421. Autor. https://www.inm.gob.mx/gobmx/word/index.php/tema-migratorio-130421/ [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (INSP). (2021). Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (Ensanut) Continua 2021. Centro de Investigación en Evaluación y Encuestas (CIEE) [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2022a). Climate change 2021: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2022b). Climate change and land [Informe especial]. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2018). The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Africa.https://zenodo.org/record/3236178 - .Y-6AvOxBxQY [ Links ]

Isacson, A. (30 de octubre de 2021). Weekly U.S.-Mexico Border Update: 2021 migration numbers, caravan in Chiapas. Remain in Mexico, CBP Facebook group. Washington Office on Latin America. https://www.wola.org/2021/10/weekly-weekly-u-s-mexico-border-update-2021-migration-numbers-caravan-in-chiapas-remain-in-mexico-cbp-facebook-group/ [ Links ]

Jelin, E. (2021). Género, etnicidad/raza y ciudadanía en las sociedades de clases. Nueva Sociedad, 293, 39-62. [ Links ]

Kuusipalo, R. (2017). Exiled by emissions – climate change related displacement and migration in international law: Gaps in global governance and the role of the UN Climate Convention. Vermont Journal of Environmental Law,18, 614-647. [ Links ]

Laczko, F. y Aghazarm, C. (2009). Migration, environment and climate change: Assessing the evidence. IOM. [ Links ]

Leutert, Stephanie (2018). Organized Crime and Central American Migration in Mexico Project. The LBJ School of Public Affairs/University of Texas. [ Links ]

Light, M. y Miller, T. (2018). Does undocumented migration increase violent crime? Criminology, 56(2), 370-401. [ Links ]

Llain, S. y Hawkins, C. (2020). Climate Change and Forced Migration. Migraciones Internacionales, 11. https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.1846 [ Links ]

Llorente, D. (2014). Lucha de clases y democratización en Centroamérica. Trayectorias y legados históricos [Tesis de doctorado, Universidad de Salamanca]. https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/124173/DDPG_LlorenteSánchezDavid_Tesis.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Lorber, J. (1994). Gender Paradoxes. Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Mies, M. (1998). Patriarchy & accumulation on a world scale. Women in the international division labour. Zed Books. [ Links ]

Miranda, B. (17 de marzo de 2021). El Corredor Seco de Centroamérica, donde millones de personas están al borde del hambre y la pobreza extrema por el Coronavirus y los desastres naturales. BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-56407243 [ Links ]

Moore, J. (2016). Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. PM Press. [ Links ]

Moreno, J. M., Laguna-Defior, C., Barros, V., Calvo Buendía, E., Marengo, J. A. y Oswald Spring, Ú. (Eds.) (2020). Adaptation to climate change risks in Ibero-American countries: RIOCCADAPT Report. McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Muñoz, R. (2020). Los más devastadores huracanes de este siglo en Centroamérica y el Caribe. DW. https://www.dw.com/es/los-m%C3%A1s-devastadores-huracanes-de-este-siglo-en-centroam%C3%A9rica-y-el-caribe/a-55548254 [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas (16 de mayo de 2022b). Presentan ACNUR y OIM primer reporte sobre proyecto piloto para la inserción socioeconómica de personas haitianas en México. OIM/ACNUR. https://mexico.un.org/es/182041-presentan-acnur-y-oim-primer-reporte-sobre-proyecto-piloto-para-la-insercion-socioeconomica [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas (2020). América Latina y el Caribe: La segunda región más propensa a los desastres. https://news.un.org/es/story/2020/01/1467501 [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas. (2015). Declaración y plataforma de acción de Beijing. Declaración política y documentos resultados de Beijing+5. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/CSW/BPA_S_Final_WEB.pdf [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas. (2018). La Agenda 3030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Una oportunidad para América y el Caribe. Naciones Unidas. [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas. (2022a). Informe del Comité contra la Desaparición Forzada sobre su visita a México en virtud del artículo 33 de la Convención. OACDH. https://hchr.org.mx/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Informe-de-visita-a-MX-del-Comite-contra-la-Desaparicion-Forzada-abril-2022.pdf [ Links ]

Niva, V. (2022). Global migration and the complex interplay between environmental and social factors. Mother Pelican. A Journal of Solidarity and Sustainability, 18 (1). http://www.pelicanweb.org/solisustv18n01page10.html [ Links ]

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (2020). Desastres naturales en América Latina y el Caribe 2000-2019 [Informe]. United Nations. [ Links ]

Ortega, A. y Morales, L. (2021). (In)seguridad, derechos y migración. La Guardia Nacional en operativos migratorios en México, Revista IUS, 15(47), 157-192. [ Links ]

Oswald Spring, Ú. (2008). Gender and disasters. Human, gender and environmental security: A HUGE Challenge (Publication Series of UNU-EHS, núm. 8/2008). UNU-EHS. [ Links ]

Oswald Spring, Ú. (2014). Seguridad de género. En F. Flores-Palacios (Coord.), Representaciones sociales y contextos de investigación con perspectiva de género (pp. 225-256). CRIM-UNAM. [ Links ]

Oswald, Ú. (2020a). Earth at Risk in the 21 st Century . Springer. [ Links ]

Oswald, Ú. (2020b). Reconceptualizar la seguridad y la paz. CRIM-UNAM. [ Links ]

Oswald, Ú., Serrano, S. (2014). Vulnerabilidad social y género entre migrantes ambientales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Padilla Pérez, R., Quiroz Estrada, V. y Villarreal, F. G. (2020). Retos y oportunidades para atraer la inversión de la diáspora salvadoreña en los Estados Unidos hacia iniciativas de desarrollo en El Salvador. Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2020/100; LC/MEX/TS.2020/22). CEPAL. [ Links ]

Pahl-Wostl, C, Bhaduri, A. y Gupta, J. (Eds.) (2015). Handbook on water security. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Pérez-García, J. N. (2020). Situación de la gestión del riesgo de desastres en Centroamérica. Repertorio Científico, 23 (2), 112-119. [ Links ]

Prieto, S. (2021). Southern Border (of México?): disputed territories, megaprojects and (im)mobilities, Academia Letters, 933. [ Links ]

Reardon, B. (1996). Sexism and the war system. Syracuse University Press. [ Links ]

Reardon, B. y Snauwaert, D. (2015). Betty A. Reardon: A pioneer in education for peace and human rights. Springer. [ Links ]

Red de Documentación de las Organizaciones de Defensa del Migrante (Redodem). (2020). Migraciones en México: fronteras, omisiones y transgresiones. Informe 2019 . Autor. [ Links ]

Ruiz, A. (2020). Un año después del Acuerdo Estados Unidos-México. La transformación de las políticas migratorias mexicanas. Migration Policy Institute. [ Links ]

Salazar, S. (2019). Las caravanas migratorias como estrategia de movilidad. Revista de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana, 14(27), 111-144. [ Links ]

Sassen, S. (2021). Border regions, migrations and the proliferation of violent expulsions. En N. Ribas-Mateos, M. Zambrano y T. J. Dunn, Handbook on human security, borders and migration (pp. 285-299). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Serrano, S. (2021) (Ed.). Diseño de una metodología triangulada de indicadores cualitativos y cuantitativos, que evalúe la prevalencia de la violencia política por razón de género en México y su impacto en el ejercicio de los derechos políticos de las candidatas a puestos de elección popular en el proceso electoral federal 2020-2021. CRIM-UNAM-INE. [ Links ]

Srigiri, S. R. y Dombrowsky, I. (2022). Analysing the water-energy-food nexus from a polycentric governance perspective: Conceptual and methodological framework. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10(725116). [ Links ]

Steffen, W., Rockströ, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T., Folke, C., Liverman, D., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A., Cornell, S., Crucifix, M., Donges, J., Fetzer, I., Lade, S., Scheffer, M., Winkelmann, R. y Schellnhuber, H. (2018). Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. PNAS, 11(33), 8252-8259. [ Links ]

Terminiello, J. (2014). Dictatorships, refugees and reparation in the southern cone of Latin America. Forced Migration, 45, 90-92. [ Links ]

The Economist (15 de enero de 2022). Business and the state. The new interventionism [Reporte especial]. The Economist.https://www.economist.com/special-report/2022-01-15 [ Links ]

Toscano, J. (2017). Climate Change Displacement and Forced Migration: An International Crisis. Arizona Journal of Environmental Law and Policy, 6(1), 457-490. [ Links ]

Tovar, H. (12 de enero de 2022). Asesinaron a 171 mujeres en Juárez durante el 2021. El Heraldo de Juárez. https://www.elheraldodejuarez.com.mx/local/juarez/asesinaron-a-171-mujeres-en-juarez-durante-el-2021-7716838.html [ Links ]

Transparency International (2021). Corruption of Latin America and the Caribbean. Perception of Corruption. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021?gclid=CjwKCAiA2fmdBhBpEiwA4CcHzWnZHmQOrpwwawgdEowz7n1IIUwngAiWZxTuMDBEbrazCWNYg3zQaxoCmnAQAvD_BwE [ Links ]

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) (2011). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision. United Nations. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (1994). Human Development Report: New Dimensions of Human Security. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2003). Human Security Report: Human Security Now. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2002). Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Autor. [ Links ]

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2017). The Adaptation Gap Report 2017. UNEP . https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/22172/adaptation_gap_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. Autor. [ Links ]