Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Frontera norte

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0260versión impresa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.34 México ene./dic. 2022 Epub 10-Feb-2023

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2289

Articles

Correlation of Trade, Competition, and Anti-Corruption Regulations between Mexico and the United States

1Universidad de Monterrey, México, ruben.lealb@udem.edu

To make public policy recommendations, the deductive method with a qualitative approach was used to identify the empirical correlations between trade, competition, and anti-corruption regulations between Mexico and the United States, within the framework of USMCA. In the light of the findings, it is recommended to limit to a minimum the exceptions available in trade agreements that aim to restrict the application of domestic laws on economic competition and anti-corruption, as well as to standardize the use of the “rule of reason” in competition between administrative and judicial authorities in both countries to harmonize and provide certainty to international transactions and binational production chains. The limitations of this research are those inherent to the subjectivity of the deductive method, but it provides unpublished results as a ground for further investigations.

Keywords: international law; economic competition; anti-corruption; Mexico; United States

Con el objetivo de hacer recomendaciones de política pública, se utilizó el método deductivo con enfoque cualitativo para identificar las correlaciones empíricas entre las regulaciones de competencia, comercial y anticorrupción entre México y Estados Unidos, en el marco del T-MEC. A la luz de los hallazgos, se recomienda limitar al mínimo las excepciones invocables en los tratados comerciales que tengan por objeto restringir la aplicación de la legislación doméstica de competencia económica y combate a la corrupción; así como homologar la utilización de la “regla de la razón” en materia de competencia entre las autoridades administrativas y judiciales de ambos países para armonizar y darle certidumbre a las transacciones internacionales y cadenas de producción binacionales. Las limitantes de esta investigación son las inherentes a la subjetividad del método deductivo, pero se aportan resultados inéditos para continuar con el estudio en estos temas.

Palabras clave: derecho internacional; competencia económica; anticorrupción; México; Estados Unidos

INTRODUCTION

The United States, Mexico, and Canada Agreement (USMCA) requires that the three countries apply antitrust laws, as well as mechanisms to fight corruption. It is important to remark that the protected legal asset in the three fields analyzed in the present document—antitrust laws, international trade regulation and anticorruption regulations—is the same: the defense of market efficiency. This way, it is sought to increase social welfare by mechanisms such as reducing consumer prices, improving the quality of goods and services, and increasing investment and employment, all of this within an effective competition framework.

Although the countries have the sovereignty to establish antitrust and anticorruption laws and policies, each of them is also enabled to apply its internal legislation to actions performed in other country, as long as a jurisdiction link between the action and the performers can be proved (Gobierno de México, 2020). However, there are exceptions that each country may call to prevent the application of antitrust legislations. According to USMCA, these exceptions shall be legislative and substantiated in national interests or in public policies. In this document we do not intend to elucidate what national interest is, hence, the conclusion will be the proposing of public policies.

Each country undertook to have its own economic antitrust legislation and appoint governmental agencies to enforce it. In this regard, USMCA requires that domestic antitrust authorities offer a treatment that favors national and foreign agents in like manner. Mexico and the United States committed to respecting the jurisdictions and only appeal when there is harm to economic activities in the respective country. In point of fact, similar to the MFN Treatment principle (Most-Favored-Nation) in international trade (World Trade Organization, 1995, p. 306), USMCA demands processual equality in the application of local antitrust laws.

USMCA Chapter 21 (Gobierno de México, 2020) has as a ruling principle the protection of consumers, as well as maintaining efficient and competitive markets. With this, it is intended to improve the welfare of the citizens of the signatory countries. To achieve this goal, additional to the antitrust laws, each country also undertakes to have a valid legislation for consumer protection and punish fraudulent trade practices or that lead to errors.

Furthermore, Chapter 27 defines the mechanisms to fight bribery and corruption in trade and in international investments. In the terms of this agreement, countries concurred to adhere to the Organization of American States, OAS (1996), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD (1997) and UN Office on Drug and Crime (2003). With this a common denominator in terms of corruption combat in the context of public international law is guaranteed.

It is worth remarking the importance of the link between Mexico and the United States because, as of February 2021, Mexico retook its position as a main trade partner of the U.S. (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2021), a rank it had lost to China. Out of the total U.S. foreign trade in the month above, Mexico had a share of 15.3 percent, while China 13.7. Additionally, in March 2021, foreign trade between Mexico and the United States reached a historic peak of 56.908 billion USD.

Particularly important is the relationship between Mexico and the State of Texas because the largest volume of exportations over the last 16 years has been with this state; reaching more than 260 billion USD a year (Texas Economic Development, 2021). To contextualize each country in its own dimension, Table 1 shows macroeconomic indices.

Table 1. Binational macroeconomic indices

| Index | Year | Mexico | United States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product (Billion USD) | 2020 | 1 076 | 20 932 |

| Population (Million people) | 2020 | 128 | 330 |

| Per capita GDP | 2020 | 8 421 | 63 416 |

| Global exportations (Billion USD) | 2019 | 461.1 | 1 645.6 |

| Global importations (Billion USD) | 2019 | 467.3 | 2 568.4 |

| Global Competitiveness Index | 2018 | 4.29 | 6.01 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration with data from WTO (2020) and World Bank (2021).

In USMCA, Mexico and the U.S. agreed, in addition to rules for commercial interchange, to co-operate regarding antitrust regulation and corruption combat (Gobierno de México, 2020). Moreover, there are correlations between the topics above that may be elucidated from regulations, policies, punishments and trade flows between both countries. The goal of the present article is to identify the correlations in relation to trade, antitrust and anticorruption activities between these countries. After studying such correlations and their outreach, public policy recommendations will be made with a view to strengthening the national governments’ institutional capabilities for the benefit of their citizens.

Following, the regulatory and conceptual antitrust framework the North American region will be analyzed, particularly the Mexican and U.S. cases, without losing sight of the substantial differences between the countries. Then, the deductive method will be utilized with a qualitative approach to define the correlations and limits regarding antitrust and trade regulations between the countries. Finally, the interrelation of such regulations with rules related to corruption combat will be reviewed. Establishing these correlations will allow us, in the final section of the document, to make integral public policy recommendations in line with social welfare.

CONCEPTUAL ANTITRUST FRAMEWORK IN NORTH AMERICA

For the purpose of understanding the regulatory antitrust interrelations between Mexico and the United States, it is necessary, in the first place, to establish the conceptual trends and recent legal applications. For the purposes of the present article, the economic foundations that justify legal antitrust regulations will not be approached,2 nor the necessity for State regulation in economy, for such theoretical framework surpasses the scope of the present research.

In 1889, Canada was the first country in the world that banned collusive agreements in its economy by means of decreeing antitrust restrictions. A year later, the U.S. regulated competition by means of the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), which is still in force. These North American countries were the first to punish monopolies and set restrictions on trade flows considering the damage they do not only to free market, but society as a whole (Stanford, 1978).

The United States and Canada inspired (or pressured) Mexico to draft, in its own terms, the current constitutional article 28 in 1917. However, it was a disposition with no practical application up to 1992 due to the absence of a secondary regulation to give legal life to institutions that foster free competition. Early in the 1990’s decade, the promotion of legislation, institutions and antitrust policies was not in the Mexican State agenda. Instead, it was in the context of the negotiations of the extinct NAFTA, in which one of the requirements of the three countries was to have antitrust protections for foreign investment before mutually opening their markets.

In this way, the first antitrust law in Mexico was promulgated in 1993, more likely due to international pressure to sign a trade agreement than an initiative by a Mexican legislator. It was necessary, back then, that the U.S. and Canada protected their markets and conationals from monopolistic foreign threats. The only mechanism they had was to ask for laws and institutions to protect them in the countries where they would place their products and services free form tariffs, while conversely, foreign monopolies might access their domestic markets without restrictions.

According to Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica [Federal Antitrust Commission] (2018), the legal antitrust framework in Mexico has organically evolved to adapt to an economic environment in constant change. We can divide this evolution into three stages: the first lasted 10 years and comprises a learning stage; the second, another 10 years, over which antitrust policies strengthened; and finally, the third stage corresponds to the years after the 2013 constitutional reforms, when antitrust policies consolidated as a polity of the Mexican State.

Following, the Mexican and U.S. cases are analyzed on their own and then interrelated, according to their chronologic appearance. Logical conclusions are drawn from the propositions established in the two following sections by country. We start from general propositions such as international agreements, national laws and domestic policies to accomplish the particular correlations in specific cases.

The Case of the U.S.

The country where most academic discussions and antimonopoly activities have taken place is the United States. Following Kate Thielen’s (2004) academic overview, it is possible to notice the academic richness of the U.S. debates and discussions that started in 1890 with the promulgation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. It fought the trusts3 that intended to unite economic agents that were mutual competitors in order to later share the revenues between the shareholders. Likewise, this legislation stated the illegality of the figure of monopoly and total restriction to trade inside the U.S.

The antitrust regulations in the U.S. are drafted in a very concise and general manner so that judges interpret them. This offers firms little certainty to be able to meet the regulation. The Sherman Act was criticized since following its drafting, virtually all trade agreements somehow restricted trade. That is to say, when a firm legally tried to prevail over its competitors, it could infringe the generic rule.

However, the legal interpretation prevented the legislation from also banning agreements with capacity to create economic efficiencies that benefitted consumers and society (Peckham, R. W. and Supreme Court of The United States, 1898). The ministers of the Supreme Court argued that some agreements were necessary to make trade feasible, even if some competitors were eliminated. According to Hazlett (1992), banning all the agreements that restricted trade would be establishing there should be no trade. In fact, Sherman Act enables individuals or enterprises that suffered losses from antitrust practices to claim damages before federal courts.

In the case Addyston Pipe and Steel Co. vs. the United States (1899), the Supreme Court established a distinction between open restrictions (agreements whose single goal is to restrict competition) and collateral restrictions (agreements where competition restriction is a goal subordinated to the legitimate goals of the firm). The resolutions of the Supreme Court recognize that the agreements that restrict trade may at once create efficiencies from economies of scale.

The conclusion of the Supreme Court was that the purpose of Sherman Act was not to ban all the agreements that restricted trade per se, but only those with the single purpose of restricting trade in terms of free competition. Though, since the efficiencies or concentrations from trade restrictions may not always be quantified, the U.S. antitrust policy hardened gradually from 1898 to 1968, when the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice issued a theoretical approach to assess the effects of efficiency in market concentrations (U. S. Department of Justice, n.d.).

In 1914, the U.S. Congress issued Clayton Act to strengthen the antimonopoly legalization of Sherman Act. While the latter banned any collusive practice that restricted trade, the fixing of prices and economic cartels, the former, Clayton Act (1914, p. 1), restricted behaviors that “substantially decreased competition” such as concentrations via merges or takeovers, for which it defined an in-advance notification system, similar to the one presently in effect in Mexico via Ley Federal de Competencia Económica, LFCE [Federal Antitrust Law] (2014).

Decades later, in the University of Chicago, Robert Bork (1978) published a harshly critical book on the U.S. antitrust policy so far. The book propitiated a heated debate between scholars and authorities, as it described the way such policy, in its endeavor to rigorously protect competition, had turned over time into an obstacle for economic growth and an enemy for consumers as it inhibited economic activity and prevented reaching economies of scale by means of merges of firms.

As a solution to facilitate the consideration of efficiencies in the context of the current U.S. legislation, Bork (1978) put forward leaving the interpretation of competition as a rivalry process behind, and instead defining it as a stage in which the consumers’ welfare is the main goal of public policies. That is to say, the author links the concepts of competition and maximization of consumer’s welfare; according to his proposal, competition should not be pursued for the sake of it, but for the consumers’ welfare.

This academic debate started by Williamson (1969) ended up being called the Chicago School, which became the seed for U.S. antitrust policies to change as of the 1980’s, being much more permissive of mercantile operations that restrict competition if they generate efficiencies. In fact, virtually all vertical concentrations (that is to say, along the production chain, not among competitors) were approved in the same decade.

According to this new paradigm in the U.S. antitrust policy, trade restrictions in agreements were usually incompatible with the principal goal of all firms: the maximization of their revenues. This means that trade restrictions were made out of considerations of economic efficiency, not to damage the sphere of competition. This new permissive stance of the regulatory authority implied that the damage caused by intervening the markets when it was not necessary was greater than the damage caused by not intervening if it was necessary (Hovenkamp & Scott Morton, 2020).

However, this tendency lasted very shortly. In the 1990’s decade, the rigorousness of antitrust policies in the U.S. reappeared with the “post-Chicago” school of thought (Hovenkamp, 1985, p. 225). This school supported, in opposition to the Chicago School the previous decade, that antitrust intentions in restrictive trade agreements may be rational under certain circumstances. That is to say, there is matter to contest certain sorts of antitrust agreements when these cannot demonstrate explicit efficiencies (Hovenkamp, 2001).

To sum up, prior to the Chicago School, agreements with anti-competitive issues were virtually penalized immediately. In the 1980’s, under the tenets of the Chicago School, vertical agreements and concentrations were allowed, though as of the 1990’s, following the philosophy of the Post-Chicago School, the efficiencies that agreements generate are particularly analyzed, while their effect on social welfare, understood as the addition of the welfare of consumers and producers, researched (Baker et al., 2002).

This new measurement standard produced what we know today as the “Rule of Reason”. While previously, the prohibition of an activity made it illegal because of the activity itself, now according to the rule of reason, an activity is not illegal because of what is done, but because of the effect it has (Loevinger, 1964). In comparison with Mexico, absolute monopolistic practices are fully prohibited, that is to say, the mere fact of acting in such manner is sufficient for its illegality. Not so, relative monopolistic practices, which are punished according to the effects they produce on the market.

Managing a full prohibition is much simpler than the rule of reason. To apply a prohibition only proving the deed is needed, however, in order to apply the rule of reason, it is necessary to calculate the effects of the activity, and these calculations are always debatable. Under the rule of reason, an action is assessed by its effects in favor or against competition. When the effects in favor of competition are greater than those against, the activity is not considered illegal (Yvon, 2006).

The academic debate explained by Kobayashi and Muris (2012) focuses on the definition of the welfare reference index, which has to be clearly understood in order to differentiate anticompetitive effects from those that produce efficiencies. In this debate, three groups are identified: supporters of welfare-consumer (which only take the surplus of consumers as a reference in the analysis); those of welfare-price (only the agreements that offer a decrease in prices as a result are authorized); and welfare-social (which use the addition of the surplus of consumers and producers). The Chicago School supported the consumers’ welfare, while the Post-Chicago School, social welfare (Hovenkamp, 1985).

The welfare standard that prevailed and is still in force up to 2022 is that of social welfare. As a matter of fact, this is the standard also applied in Mexico. Such welfare standard considers that the returns of producers are as important as the benefits for consumers. In theory, anticompetitive effects (such as price rises) and competitive ones (cost savings) may be directly expressed in this social welfare standard. It is proposed to broaden this common denominator not only for an analysis of economic competition or international trade, but also considering it an aggravation when assessing the harmful effects of corruption practices.

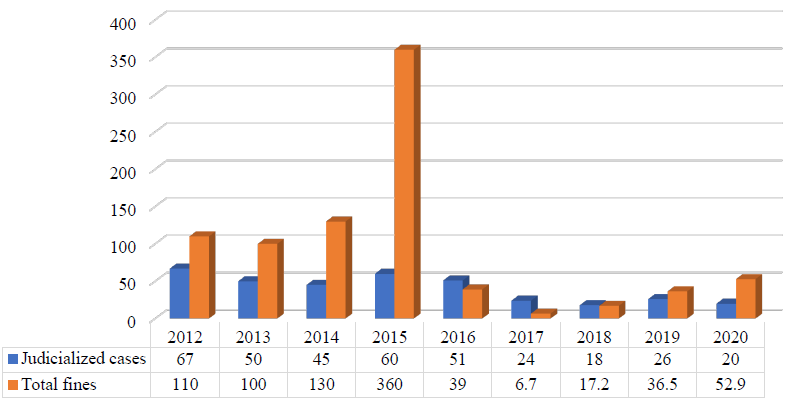

Hovenkamp (2010) analyzes antitrust topics in the United States. Additionally, it is important to notice that over the last 10 years, the persecution of infringements to antitrust regulations in the U.S. has experienced important ups and downs. In graph 1, the total of judicialized cases regarding antitrust regulations is shown, also the value of fines a year. Fines are in hundred million USD.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from U. S. Department of Justice (n.d.).

Graph 1. Number of judicialized cases and fines regarding antitrust issues in the United States

In the data above, a relaxation is observed in the policy to fight monopolies and trust practices in the U.S. over the second half of last decade. Even discounting the atypical year of 2015, which had a peak value in fines imposed, on average both the total of judicialized cases and the total of fines dropped as of 2016, concurring with a more restrictive trade policy applied under Trump. The average of judicialized cases and total fines between 2012 and 2014 is three times higher than that recorded between 2016 and 2018. This relaxion signaled to the markets as regards persecution, in this way, anticompetitive activities became more lucrative, from a purely pragmatic standpoint.

The Case of Mexico

In Mexico, the inception and development of antitrust laws and policies have been deeply related to the evolution of foreign trade policies. Its origin was not the study of the adverse effects of anticompetitive activities on efficiency or the welfare of society, as in the U.S.; nor the desire of eradicating the deeply-rooted problem of corruption. Neither was it in searching for mechanisms to prevent armed conflicts, as in Europe. In Mexico, trade policy influenced, due to external pressure, to initiate antitrust regulations (Leal Buenfil, 2021).

Prior to the 1980’s decade, the Mexican economy was distinguished by being isolated from international trade, setting up an industrialization policy via importation substitution. As explained by Romero (2003), this schema intended to prevent the entrance of products from other countries to foment their production in the country. With this, according to the logic of importation substitution, the country will be industrialized and wealth created. According to the proponents of this model, if Mexico was able to produce bicycles, then no bicycles shall be imported and so the national bicycle industry would strengthen.

This commercial protectionism, according to Anaya Ayala, Ruiz Torres and Trejo Guzmán (2009), led to a period of scarce economic competition in Mexico. The national enterprises had an inefficient local approach. They had no incentives to export nor to compete abroad, since the national market was captive and exclusive. Simultaneously, firms that were property of the government grew disproportionately, as greater governmental participation in the economy was sought with a view to controlling it. Such trade policies sacrificed productive efficiency and were a breeding ground for the development of corruption and the “economy of compadrazgo” (Haber, 2002, p. 127).

After the 1982 economic crisis and the application of liberal policies by the federal government, the model changed toward free market (Witker & Varela, 2003). The earliest changes were in the legal sphere, with the privatization of public enterprises and strengthening the supervising capabilities of the government in the economy, as substitutes for the participatory capacities (Sacristán Roy, 2006). The most representative examples were the privatization of the banking system and Teléfonos de México (Telmex),4 though they were not the only ones. The privatization of public enterprises and regulatory adjustments in favor of free market were the rule over the 1980’s and 90’s.

Already in the 1917 Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (CPEUM) [Political Constitution of the United Mexican States], article 28 banned monopolies. However, this was a dead letter for 75 years (Leal Buenfil, 2021). By and large, in addition to banning monopolies, this article created monopolistic exceptions in favor of State activities in certain areas considered strategic. In 1983, a constitutional reform to the thus far inoperative article 28 extended the prohibition of monopolistic behaviors to private individuals. However, the first large quantitative antitrust leap took place in 1993 with the promulgation of the extinct Ley Federal de Competencia [Federal Competition Law], and later in 2014 with LFCE.

In international treaties, Mexico has agreed to set up co-operation and assistance mechanisms in antitrust proceedings. However, so far in North America no supranational authority has been appointed to issue recommendations or penalties, whose function is the same as that of the European Commission. With this, the countries that signed USMCA have only had assistance cooperation in this regard. Presently, Mexico has antitrust dispositions in agreements celebrated with the United States, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, Chile and Canada (Leal Buenfil, 2021).

Mexico partially adopted, from its legislation and jurisprudence, the rule of reason to assess and punish anticompetitive actions (García, Serralde, & Kargl, 2015). However, this rule is not a well-established nor a fully-defined concept, rather, it undergoes continual evolution in the U.S. and Mexico. As increasingly complex cases are solved, the rules and criteria to assess the effects of the activities are defined. This discussion reached Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación [Supreme Court of the Nation] (2016), where the application of the rule of reason to monopolistic practices is clarified, though it is not extended to absolute monopolistic practices, where the rule per se rule is applied, not the rule of reason: “Monopolistic practices. Article 28 of the Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos bans them not only when this deed has as a goal to increase prices” (Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, 2016, p. 1).

In the modern conceptualization of the rule of reason, the efficiency generated by an activity is taken as a justification to execute it. From this standpoint, efficiencies favor the legality of activities. There are scholars, among which distinguishable are Ross and Winter (2005), and Renckens (2007), who argue in favor of counting market efficiencies to justify the legality of certain monopolistic practices. These criteria are not homogeneous in Mexico and the U.S. because, to begin with, their legislations have different conceptions.

Particularly, in Mexico, a mixture of criteria is used. Absolute monopolistic practices, as typified in LFCE (2014) and in the current Código Penal Federal (CPF) [Federal Penal Code] (CPF, 1931), are punishable just for committing them; while for relative monopolistic practices and illicit concentrations a sort of rule of reason, adapted to the Mexican context, is utilized, as set forth in Article 55 of LFCE (2014).

One of such criteria replicated in Mexico after the U.S. case is the analysis of relative monopolistic practices based on market power. In general, when a firm that does not have market power performs an anticompetitive practice, it is not likely that such behavior has considerable anticompetitive effects. Although the Mexican antitrust tradition is relatively recent, it has experienced a noticeable evolution over the last few years (López-Velarde, 2017). Implications for trade and corruption combat will be analyzed in the following sections.

BINATIONAL CORRELATION BETWEEN TRADE AND ANTITRUST REGULATIONS

Regulations, policies and interpretations of the antitrust law between Mexico and the U.S. are closely related. Not only is this correlation linked in its development over the 1990’s to the extinct NAFTA, but it also starts from its conceptualization as a State policy and goes beyond.

On occasion, regulations and governmental policies set barriers for economic competition (Bhattacharyyaa, Bhattacharyya, & Kumbhakar, 1996). Analogously, some barriers for free trade also come from legislation and State policies. Regardless of origin, by general rule, barriers to free competition, free trade as well as corruption practices distort market efficiency and reduce social welfare, as it has been discussed in this article.

Commonly, market inefficiencies increase prices and restrict production, decreasing the consumers’ welfare and causing social losses (Stout, 2003). Such inefficiencies may come from two sources: actions in the domestic market pursued by the economic authority, or international market actions which, owing to productive integration, allow for the introduction of goods into the national market.

From this standpoint and in the face of national economies increasingly integrated into international markets, we shall consider at once trade and antitrust policies to defend social welfare. This is valid for Mexico and the U.S. individually as well as jointly, considering their links and economic interdependency. According to WTO (2020), the main destination of Mexican imports is the U.S.

Some evidence points out that the same producers with substantial market power in their country of origin are able to unfold depredatory price practices in foreign markets when they export their products (Sokol, 2007). Such is the case of caustic soda from the U.S., which was penalized for dumping5 in Mexico, imposing compensatory fees according to the resolution published in Diario Oficial de la Federación [Official Journal of the Federation] about the case (Secretaría de Economía, 2020). In the first place, the exporter of this product has a dominant position, almost monopolistic, in the U.S. domestic market, in this way, its power in the U.S. market allowed it to distort the market in Mexico.

Interrelations between regulations and antitrust policies between both countries are made explicit in article 86 of Ley de Comercio Exterior (LCE) [Foreign Trade Law], in which, in reference to the proceedings to establish safekeeping measures, it is established that if the Secretariat of Economy “considers there are elements that allow supposing that any of the parties carried out monopolistic practices punishable in the terms set forth in the law (LFCE), it will notify the corresponding authority” (Ley de Comercio Exterior, 1993, p. 24).

In this regard, it is interesting that the linking of trade protection measures with those of corrective nature for the competition of local market is made in the trade legislation, not in the antitrust regulation. However, USMCA’s Chapters 21 and 27 clarify this correlation resorting to the analytical method to grasp its scope.

The history of trade performance in a context of free competition may be analyzed in a quantitative manner as well. As of 1993, when Mexico promulgated its first secondary antitrust legislation, whilst in parallel NAFTA came into force, significant changes have been noticed in its indicators of foreign trade with the U.S., as displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Evolution of trade between Mexico and the United States after NAFTA and the Mexican antitrust legislation

| 1993 Beginning |

2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 Beginning |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of | Possible | Possible | Possible | New | of | |

| NAFTA | effects | effects | effects | LFCE | USMCA | |

| Mexico exports to U.S. | 42 912 | 147 400 | 183 563 | 238 684 | 308 870 | 338 701 |

| Mexico imports from U.S. | 45 295 | 127 534 | 118 547 | 145 007 | 186 812 | 167 762 |

| Balance of trade | -2 383 | 19 866 | 65 016 | 93 677 | 122 057 | 170 939 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from Secretaría de Economía (2021) and Sistema de Información Económica (2021).

Table 2 qualitatively shows that trade between Mexico and the U.S. has steadily grown since the free trade agreements were signed, with their entailed antitrust regulations. Likewise, in the binational balance of trade, it is noticed Mexico exports a substantially larger amount than the U.S., going from a negative balance in 1993 to have an increasingly larger surplus balance.

Both in Mexico and the United States, practices or behaviors that undermine the economic welfare of the society are called monopolistic practices. These illicit behaviors have as a goal to artificially maintain high revenues for producers, depredating the markets where these actions are carried out, even damaging markets vertically or horizontally related (Witker & Varela, 2003).

Regardless of the country, what is important is that they echo on the national market of a third country as they distort the optimal economic results that a free-market economy should have. In this way, the correlation of trade and antitrust regulations between these countries has been documented. In the following section, we will analyze the scope and implications of this correlation.

Correlation between trade and antitrust regulations

The application of an antitrust legislation is affected by public policy considerations such as a commercial strategy or national security (Motta, 2018). In this regard, for most of the XX century, Mexico kept a policy of import substitution for the purpose of industrializing the country. Later on, by the end of the century, the approach changed to one of commercial aperture and liberalization, which required modifications to the Mexican legislation.

The industrialization model via importation substitution had as a secondary effect, or collateral damage, concentration in national markets and corruption of State enterprises. Though, not only was there in Mexico a pernicious relationship between trade and antitrust policies, also in the U.S., the Webb-Pomerene Act (1918) permits the existence of economic cartels when these are exclusively engaged in foreign trade and as long as they restrict neither domestic competition nor U.S. competitors’ exportations.

In this way, it is evinced that national antitrust policies may be used for accomplishing trade policy goals such as general or sectoral protectionism. The clearest example are antidumping policies. The goal of such policies is to prevent foreign firms from selling in the national territories at less than production costs, or else, below the price in their countries of origin (WTO, 2021). The justification is that such actions may eliminate national enterprises and disloyally impose foreign ones in the internal market. However, antidumping regulations may also be perversely utilized to illegally protect national firms from more efficient foreign competitors.

What occurs in trade policy takes place in industrial policy. In Mexico, CPEUM’ Article 27 allows the State to orient national development. With this, governmental fomentation and support to industries considered strategical are legalized. Under this supposition, industrial policy might head toward benefitting certain sectors deemed transcendental. Albeit, Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica (2018) suggests that an antitrust policy is the best possible industrial policy. When enterprises are protected from competition or allotted with subsidies, the most likely is that they become less efficient over time. For many years this took place in Mexico causing the distortion of competition and propitiating corruption between economic agents and governmental regulators.

In this sense, the trade policy of delivering governmental subsidies for national firms with a view to strengthening them against foreign enterprises may be considered an attack on free economic competition. This distorts the efficient allotment of resources in the markets, as less efficient firms are able to survive at the expense of more efficient ones, those that pay taxes, with which subsidies are afforded. However, in the international legal regime of foreign trade there is a regulation for subsidies in WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (WTO, 2008), which are not banned and have the potential to affect free competition and free trade if they are abused.

According to Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica (2017), in Mexico, trade policy affects free concurrence and competition in national markets when it generates barriers or sets unjustified requirements to enter a market. In like manner, when inside a production chain supply options are limited, firms and consumers are affected. By and large, trade policy may distort efficient association and reduce the capacity of certain firms to compete at both sides of the Mexico-U.S. border.

Owing to this, it is necessary to define the particularities of trade policies with capacity to restrict economic competition. The effects of such policies might affect productivity and some economic agents’ rank in the market and decrease the total welfare of these countries’ societies. Once these particularities are identified, public policies may be adjusted to ensure the efficient functioning of markets, allotting resources in an optimal manner, seeking economic development.

Following the guidelines of Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica (2017) regarding trade policy, we are able to state that the process of trade aperture started in the 1990’s decade has had a noticeable impact on the growth of the Mexican exporting sector and on the conditions of domestic competition. Ever since, the Mexican market has a broader offer of products and services for the benefit of consumers, which has propitiated that prices in Mexico have a steady behavior in comparison with previous decades. Likewise, this has enabled U.S. enterprises to expand their markets and investment possibilities.

The aforementioned stability of prices benefits end consumers and enterprises, which may make better investment decisions. Collaterally, Mexican enterprises have witnessed a reduction in their market power and now have fewer chances to abuse of a dominant position, as their products may be replaced by importations (López Noria, 2015). In parallel, the Mexican and U.S. firms that are efficient and productive gain access to new markets where they compete in equal conditions, placing their products or accessing supplies with better conditions. It would be worth not losing sight that generally speaking, trade aperture fosters innovation and technologic advance, while at once, minimizes the danger of collusion between competitors (Leal Buenfil, 2021).

To sum up, and according to scientific literature, when there are trade barriers that restrict the entrance of goods and services from abroad into the domestic market, what is incentivized is the cessation of innovation by the protected national firms and thus become inefficient (De Loecker & Van Biesebroeck, 2016). A similar damage is experienced by national enterprises when, because of trade barriers, access to foreign supplies with which they may produce more efficiently is restricted, or else, savings in costs that might be eventually transferred to consumers to gain their preference in the market. In the following section, the correspondence between trade and antitrust regulations with anticorruption regulations is interrelated.

Interrelations with anticorruption regulations

To understand the interrelations of antitrust and trade regulations with anticorruption ones, we may begin with the fact that in the U.S. “even if none will tell economic antitrust laws were to become holistic anticorruption laws, indubitably they were approved bearing in mind the political influence of powerful enterprises and industrial cartels” (Wu, 2020, p. 1). In this sense, we need to run an analysis of their impact in Mexico from their interrelation with international trade in the context of USMCA.

USMCA’s Chapter 27 sets forth the general guidelines regarding corruption combat in the commercial practices of both countries. Mainly, they head toward preventing bribery in trades and in international investments. This chapter applies to any issue in USMCA, regarding trade or foreign investment. However, it is merely enunciative, since both countries agreed that both the classification of crimes, as well as their persecution and punishment, will be exclusive responsibility of each of the parties. No new crimes were created nor was a supranational, or binational, authority appointed to persecute, punish or penalize them.

Both countries agreed to typify the promise or the offer to give a public functionary an undue benefit so that they perform or not an official function. Conversely, asking or accepting an undue benefit by a public functionary to perform or not an official function was also punishable. This also applies for foreign public functionaries or with international organizations when trade or international investments are affected. In Mexico, the applicable legislation is Ley General del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción (LGSNA) [General Law of the National Anticorruption System] (2016). In this regard, countries undertake to punish embezzlement, however in all cases each country has the power to punish such actions as deemed fit. It is interesting that in the agreements to fight corruption, the keeping of accounting books, communication of financial statements as well as accountability and audit norms are established as obligations. With this, the use of the funds of firms and organizations to further corruption is prevented. All the economic agents’ accounts shall be registered in the books and there should be no records of inexistent or incorrect expenses or else, supported on forged documents.

In the context of USMCA, Mexico and the United States may be benefitted from legislating to adopt the principles in The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA, 2007), a Canadian legislation that allows public-sector employees to reveal information they believe may expose or prevent a corruption act, either it is committed by other public servants or someone else. PSDCA protects from retaliations against the public servant(s) who disclose(s) information and those involved in such disclosure.

As regards integrity promotion among public functionaries, in the Agreement, it was accorded that each country had to establish its proceedings for the selection and training of the personnel to fill the posts, especially those most vulnerable to corruption. Likewise, there shall be policies and proceedings to declare, identify and address cases of conflict of interests among public servants. This means to disclose the external activities of public servants, as well as other jobs, investments, assets and royalties. These regulations even apply to the judicial power.

Before the signing of USMCA, in the U.S., there was already a valid legislation that punished corruption practices abroad, of course Mexico was considered. It is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) (U.S. Department of Justice, 1977), which bans U.S. firms from propitiating bribes for public functionaries abroad in order to obtain or retain businesses. Its application in Mexico is recently noticed in the controversial case Walmart Teotihuacán (Corkery, 2019), which had to be investigated and punished according to Ley del Servicio Profesional de Carrera en la Administración Pública Federal [Law on Professional Career Service in Public Federal Administration] (2003).

The scope of FCPA comprises as well purchases and sales, as it is established that in the case of a failure in the fulfilment of anticorruption regulations an enterprise may have committed, the consequences may be translated to the purchasing party if no suitable investigation was carried out. Some unfulfillment instances may be found out by means of a specialized due diligence in FCPA. According to Deloitte (2007), most of the unfulfillments refer to clauses in the contracts of merges or acquisitions, and influence on the price and terms of the transaction.

In parallel to USMCA, FCPA requires that enterprises keep accounting books and records that veraciously, appropriately and specifically display their transactions. Moreover, internal control accounting systems have to be implemented and maintained to prevent economic deviations that may be at the risk of ending up among the payments punishable by FCPA and USMCA, more recently. With this, it is intended to block corruption both domestically and in international trade transactions.

The common goal of antitrust actions and combatting corruption is to make markets function efficiently and to improve the quality of life of the citizens of a jurisdiction. The interrelation of these goes beyond merely sharing the pages between USMCA’s Chapters 21 and 27. In fact, the right to economic competition is a powerful mechanism to fight corruption. Particularly, an absolute monopolistic practice, as per article 53 of LFCE (2014) is to concert or coordinate stances, or refrain from participating, in public bids, tenders or auctions. Clearly, this competition regulation aims at fighting corruption.

In fact, this antitrust regulation has criminal implications because absolute monopolistic practices are classified as a crime in Mexico. CPF article 254 bis sets forth the criminal charge that punishes those who perform anticompetitive practices that infringe free market via corruption with five to 10 years of imprisonment; this is aimed at public servants and the economic agents that collude in public bids, conspiring against the public purse.

While USMCA Chapter 21 intends to protect consumers and maintain competitive markets to improve the citizens’ welfare, Chapter 27 establishes the mechanisms to fight corruption in foreign investment and trade. It is no coincidence then that the three topics, fostering competition, combatting corruption, and regulating international trade share the same spirit and foundations. The three topics intermingle and complement one another. In fact, we have repeatedly argued that their purpose is to further common welfare by caring for the optimal functioning of the markets in conditions of equality, which produce better prices and larger supplies, quality, innovation, investment and economic growth.

PUBLIC POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Starting from the fact these are substantially dissimilar economies and countries, the judicial scaffolding in Mexico and in the U.S. allows resorting to legal mechanisms for the protection of trade such as tariffs, quotas and antidumping measures. These mechanisms may be substantiated in efficiency or simply restrict free trade and competition. Owing to this, the first recommendation is that trade policies in both countries shall consider a transversal approach to economic competition and corruption combat to maximize social benefits. In this way, it would be ensured that consumers’ welfare, producers’ surplus and market efficiency are all considered in the implementation of public policies in both countries.

A transversal perspective in public policies regarding antitrust actions, corruption combat and international trade, at both sides of the border, shall be established in the current laws of Mexico and the United States. The ideal judicial instruments would be federal laws in Mexico (LFCE, LGSNA, and LCE); whereas in the U.S., an act may be proposed, with the spirit of FCPA in mind, to establish the programmatic and transversal vision for antitrust, anticorruption and trade policies to coordinate governmental agencies in this regard (Cofece, U. S. Department of Commerce, and U. S. Department of Justice).

Although USMCA recognizes each country’s sovereignty to define antitrust laws and policies, it also allows each country to apply their domestic legislation to actions in other country, as long as a jurisdiction link may be ascertained regarding the practice or the performers. In this regard, the second public policy recommendation is to reduce as much as possible exceptions for commercial treaties that seek to bypass the application of domestic antitrust and corruption combat legislations. Particularly for Mexico, it is recommendable to reconsider the 2021 energy counter-reform; while, for the U.S., it is suggested revising agriculture protectionism, for any liberalization will produce improvements in the global efficiency and favor the citizens.

In this regard, Mexico has the right in CPEUM as well as in USMCA Chapter 8 6 to keep certain activities related to fossil fuels from competing. This allows the inception of a legal monopoly in certain economic sectors that hinder from reaching market economies as there are neither domestic nor international antitrust pressures. Moreover, it renders these economic activities more vulnerable to practices associated with corruption considering the institutional weakness that prevails in Mexico (Aguirrre-Ochoa & Gómez, 2021).

For its part, the United States maintains protectionist policies for agriculture disguised as technical measures in favor of health or environmental protection. Sheltered in what legislators and public servants define as national priorities, they have delivered subsidies to U.S. agriculturists with money from this country’s taxpayers. They have protected thus their national producers from foreign competition by means of contention mechanisms for imports via technical regulations and environmental and health care claims, which have already caused controversy in WTO (2014) as it is the case of cotton.

According to the previously analyzed “Post-Chicago” school of thought (Hovenkamp, 1985, p. 225), in order to punish anticompetitive behaviors, the efficiencies generated and their effects on social welfare, understood as the addition of the surplus of consumers and producers, have to be analyzed. In this regard, objective and consistent criteria are needed at both sides of the border to provide economic activities with certainty. Owing to this, the third suggestion is instructing coordination between antitrust authorities and judicial institutions to move toward the homologation of criteria in the application of the “rule of reason” described in this document.

This provides for investments and business plans between both countries with judicial certainty as well as fostering a more integrated and consistent North American market. Moreover, the homologation of criteria in Mexico and the U.S. as regards the way of assessing commercial practices under the same theoretical paradigm will enable economic agents to make long-term investment decisions for the region. Trade, antitrust and corruption combat rules may converge on mutual benefits for the free and efficient development of the markets.

Finally, the fourth recommendation for Mexico and the U.S. is the implementation, at legislative level, of mechanisms analogous to those in PSDPA, enabling public-sector employees to reveal information without fear of retaliation so that they can disclose or prevent corruption acts. It is suggested omitting sensible departments such as the army, intelligence agencies, as it may be counterproductive given the intrinsic characteristics of these public institutions.

In this way, the governments of both countries may generate a working environment that fosters ethics and aligns the incentives to denounce corruption without fear of personal or labor retaliation. The integrity of public servants would be an additional factor which, as the previous, allows free competition and produces efficiencies in national and international markets, increasing the quality of life of the citizens in both countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is grateful to Dr. Pedro Torres Estrada for his invaluable support for the present work. This research was carried out with funding from Puentes Consortium, Rice University (Houston, TX).

REFERENCES

Clayton Act. 15 USC §§ 12-27. (1914). Comisión Federal de Comercio. Recuperado de https://www.ftc.gov/es/enforcement/statutes/clayton-act [ Links ]

Webb-Pomerene Act. 15 U.S.C. §§ 61-68. (1918). Comisión Federal de Comercio. Recuperado de https://www.ftc.gov/es/enforcement/statutes/webb-pomerene-act [ Links ]

Addyston Pipe & Steel Co. v. United States, 175 U.S. 211. U. S. Supreme Court, 04 de diciembre de 1899. Recuperado de https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/175/211/ [ Links ]

Aguirrre-Ochoa, J. y Gómez, M. (2021). Debilidad institucional y experiencia anticrimen en México. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad, (29), 45-57. [ Links ]

Anaya Ayala, J. A., Ruiz Torres, E. y Trejo Guzmán, R. V. (2009). Evolución del derecho de la competencia en México. Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado, 42(126), 1169-1200. [ Links ]

Baker, J. B., Carstensen, P. C., Cucinotta, A., Denozza, F., Fox, E. M., Hovenkamp, H., … y Van Cayseele, P. (2002). Post-Chicago Developments in Antitrust Law. Camberley Surrey: Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2021). Indicadores. Recuperado de https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicator [ Links ]

Bhattacharyya, A., Bhattacharyya, A. y Kumbhakar, S. (1996). Government interventions, market imperfections, and technical inefficiency in a mixed economy: A case study of Indian agriculture. Journal of Comparative Economics, 22(3), 219-241. [ Links ]

Bork, R. (1978). The antitrust paradox: a policy at war with itself. Nueva York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Código Penal Federal (CPF). (14 de agosto de 1931). Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/ref/cpf.htm [ Links ]

Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica (Cofece). (2017). Política comercial con visión de competencia. Recuperado de https://www.cofece.mx/cofece/images/Promocion/Estudios-y-Publicaciones/Cuaderno-de%20promocion-1-Politica-comercial-con-vision-de-competencia-VF.pdf [ Links ]

Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica (Cofece). (2018). Competencia: Motor de crecimiento económico incluyente. Memoria del evento conmemorativo por los 25 años de la autoridad de competencia en México. Ciudad de México: Cofece. Recuperado de https://www.cofece.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Memoria-Competencia-Motor-de-crecimiento-incluyente-.pdf [ Links ]

Corkery, M. (20 de junio de 2019). Walmart pagará 282 millones de dólares para cerrar investigación de sobornos en México y otros países. The New York Times. Recuperado de https://www.nytimes.com/es/2019/06/20/espanol/america-latina/walmart-mexico-teotihuacan.html [ Links ]

De Loecker, J. y Van Biesebroeck, J. (2016). Effect of international competition on firm productivity and market power (Working Paper, núm. 21994). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Deloitte. (2007). Prácticas Anticorrupción. Ley Foreign Corrupt Practice Act (FCPA): El riesgo de no verlo todo. Recuperado de https://www.deloitte.com.mx/archivos/aseso_fin/fcpa.pdf [ Links ]

Desarrollo Económico de Texas. (2021). Comercio exterior y exportaciones. Austin: Oficina del Gobernador. Recuperado de https://gov.texas.gov/es/business/page/trade-and-export [ Links ]

García, L. G., Serralde, M. y Kargl, J. (2015). Mexico: New Antitrust Authorities and a New Federal Economic Competition Law. Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 6(1), 42-47. [ Links ]

Gobierno de México. (1 de julio de 2020). Tratado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá. Recuperado de https://www.gob.mx/t-mec/acciones-y-programas/textos-finales-del-tratado-entre-mexico-estados-unidos-y-canada-t-mec-202730?state=published [ Links ]

Haber, S. (2002). Crony Capitalism and Economic Growth in Latin America: Theory and Evidence. Washington, D. C.: Hoover Institute Press. [ Links ]

Hazlett, T. (1992). The legislative history of the Sherman Act re-examined. Economic inquiry, 30(2), 263-276. [ Links ]

Hovenkamp, H. (1985). Antitrust policy after Chicago. Michigan Law Review, 84(2), 213-284. [ Links ]

Hovenkamp, H. (2001). Post-Chicago antitrust: A review and critique. Columbia Business Law Review, 257-336. [ Links ]

Hovenkamp, H. (2010). The pleading problem in antitrust cases and beyond. Iowa Law Review Bulletin, 55-66. [ Links ]

Hovenkamp, H. J. y Scott Morton, F. (2020). Framing the Chicago school of antitrust analysis. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 168(7) 1843-1877. [ Links ]

Kate Thielen, A. T. (2004). La eficiencia económica en el análisis de competencia. In La competencia económica (pp. 43-53). Ciudad de México: Comisión Federal de Competencia. [ Links ]

Kobayashi, B. y Muris, T. (2012). Chicago, post-Chicago, and beyond: Time to let go of the 20th Century. Antitrust Law Journal, 505-526. [ Links ]

Leal Buenfil, R. (2021). Competencia económica y comercio internacional. Ciudad de México: Tirant lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Ley de Comercio Exterior (LCE) (27 de julio de 1993). Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/28.pdf [ Links ]

Ley del Servicio Profesional de Carrera en la Administración Pública Federal. (10 de abril de 2003). Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de https://www.gob.mx/sfp/documentos/ [ Links ]

Ley Federal de Competencia Económica (LFCE). (23 de mayo de 2014). Cámara de Diputados. Recuperado de https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFCE_200521.pdf [ Links ]

Ley General del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción (LGSNA). (18 de julio de 2016). Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de https://www.diputados.gob.mx›LGSNA_200521 [ Links ]

Loevinger, L. (1964). The Rule of Reason in Antitrust Law. Virginia Law Review, 50(1), 23-35. [ Links ]

López Noria, G. (2015). El efecto de la liberalización comercial sobre los márgenes de precios a costos marginales del sector manufacturero. El caso de México, 1994-2003. El Trimestre Económico, 82(327), 583-616. [ Links ]

López-Velarde, A. (2017). The Application of the Antitrust Law Under the New Rules of the Oil and Gas Industry in Mexico. Energy Law Journal, 38(35), 95-113. [ Links ]

Motta, M. (2018). Política de competencia: teoría y práctica. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Oficina contra las Drogas y el Delito. (2003). Convención de las Naciones Unidas contra la Corrupción. Nueva York: Naciones Unidas. Recuperado de https://www.unodc.org/documents/mexicoandcentralamerica/publications/Corrupcion/Convencion_de_las_NU_contra_la_Corrupcion.pdf [ Links ]

Organización de los Estados Americanos. (1993). Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte. Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/trade/nafta_s/indice1.asp [ Links ]

Organización de los Estados Americanos. (29 de marzo de 1996). Convención Interamericana contra la Corrupción (B-58) [Conferencia]. Conferencia Especializada sobre el Proyecto de Convención Interamericana Contra La Corrupción. Caracas, Venezuela. Recuperado de http://www.oas.org/es/sla/ddi/tratados_multilaterales_interamericanos_B-58_contra_Corrupcion_firmas.asp [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (16 de octubre de 2014). Estados Unidos -Subvenciones al algodón americano (upland) (WT/DS267). Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/tratop_s/dispu_s/cases_s/ds267_s.htm [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (1995). Acuerdo General sobre el Comercio de Servicios. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/docs_s/legal_s/26-gats.pdf [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (2008). Acuerdo sobre Subvenciones y Medidas Compensatorias. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/docs_s/legal_s/24-scm.pdf [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (2020). World Trade Organization data for 2019 [sitio web]. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2020_e/wts20_toc_e.htm [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (2021). Temas comerciales: Las medidas antidumping [sitio web]. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/tratop_s/adp_s/adp_s.htm [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC). (2022). Información técnica sobre las medidas antidumping [sitio web]. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/tratop_s/adp_s/adp_info_s.htm [ Links ]

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. (1997). Convención para Combatir el Cohecho de Servidores Públicos Extranjeros en Transacciones Comerciales Internacionales y Documentos Relacionados. Recuperado de https://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/ConvCombatBribery_Spanish.pdf [ Links ]

Peckham, R. W. y Supreme Court of The United States. (1898). U.S. Reports: United States v. Joint Traffic Association, 171 U.S. 505. Library of Congress. Recuperado de https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep171505/ [ Links ]

Renckens, A. (2007). Welfare standards, substantive tests, and efficiency considerations in merger policy: defining the efficiency defense. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 3(2), 149-179. [ Links ]

Romero, J. (2003). Sustitución de importaciones y apertura comercial: resultados para México. En A. Puyana (Coord.), La integración económica y la globalización: nuevas propuestas para el proyecto latinoamericano (pp. 69-120). Ciudad de México: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. [ Links ]

Ross, T. y Winter, R. (2005). The efficiency defense in merger law: economic foundations and recent Canadian developments. Antitrust Law Journal, 72(2), 471-503. [ Links ]

Sacristán Roy, E. (2006). Las privatizaciones en México. Economía UNAM, 3(9), 54-64. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Economía (SE). (2021). Balanza Comercial de Mercancías de México. Recuperado de http://www.economia-snci.gob.mx/sic_php/pages/estadisticas/ [ Links ]

Secretaría de Economía (SE). (7 de julio de 2020). Resolución por la que se declara el inicio del procedimiento administrativo de examen de vigencia de la cuota compensatoria impuesta a las importaciones de sosa cáustica líquida originarias de los Estados Unidos de América, independientemente del país de procedencia. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5596234&fecha=07/07/2020#gsc.tab=0 [ Links ]

Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890). Portal del gobierno de Estados Unidos, Estados Unidos, 02 de julio de 1890. Recuperado de https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/sherman-anti-trust-act [ Links ]

Sistema de Infomación Económica. (2021). Balanza comercial de mercancías de México. Recuperado de https://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultarDirectorioInternetAction.do?sector=1&accion=consultarCuadroAnalitico&idCuadro=CA176&locale=es [ Links ]

Sokol, D. (2007). Monopolists Without Borders: The Institutional Challenge of International Antitrust in a Global Gilded Age. Berkeley Business Law Journal, 4(1), 37-64. [ Links ]

Stanford, J. (1978). The Application of the Sherman Act to Conduct Outside the United States: A View from Abroad. Cornell International Law Journal, 11(2), 195-214. [ Links ]

Stout, L. (2003). The Mechanisms of Market Inefficiency: An Introduction to the New Finance. Journal of Corporative Law, 635-669. [ Links ]

Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. (2016). Tesis 2a. X/2016. Décima época. Amparo en revisión 839/2014. [ Links ]

The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA). (15 de abril de 2007). Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner. Recuperado de https://www.psic-ispc.gc.ca/en/public-servants-disclosure-protection-act [ Links ]

U. S. Department of Commerce. (2021). Economic indicators: Data and reports. Recuperado de https://www.commerce.gov/data-and-reports/economic-indicators [ Links ]

U. S. Department of Justice. (1977). Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Recuperado de https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/foreign-corrupt-practices-act [ Links ]

U. S. Department of Justice. (s. f.). Antitrust case filings. Recuperado de https://www.justice.gov/atr/antitrust-case-filings-alpha [ Links ]

Williamson, O. (1969). Allocative Efficiency and the Limits of Antitrust. The American Economic Review, 59(2), 105-118. [ Links ]

Witker, J. y Varela, A. (2003). Derecho de la competencia económica en México. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Wu, T. (2020). Antitrust & Corruption: Overruling Noerr (Working Paper núm. 14-663). Columbia Public Law Research. Recuperado de Https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3670&context=faculty_scholarship [ Links ]

Yvon, A. (2006). Settlements between Brand and Generic Pharmaceutical Companies: A reasonable antitrust analysis of reverse payments. Fordham Law Review, 75(3), 1883-1912. [ Links ]

2For a review of the foundations, it is suggested seeing Leal Buenfil (2021).

5“Is, in general, a situation of international price discrimination, where the price of a product when sold in the importing country is less than the price of that product in the market of the exporting country” (WTO, 2022, n.p.)

6Entitled “Reconocimiento de la propiedad directa, inalienable e imprescriptible del Estado Mexicano sobre Hidrocarburos” [Recognition to the direct, inalienable and indefeasible property of Hydrocarbons by the Mexican State] (Gobierno de México, 2020, p. 8-1).

Received: January 29, 2022; Accepted: April 18, 2022

texto en

texto en