Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Frontera norte

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0260versión impresa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.33 México 2021 Epub 13-Dic-2021

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2150

Article

Buenavistita in Maryland. An Ethnic Enclave in the International Migration

1El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, México, jinunez@ecosur.edu.mx, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8755-744X

2El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, México, tcruzs@ecosur.mx https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7714-3275

This paper aims to show the sociocultural adaptation strategy of a group of mestizo migrants from Chiapas residing in “Buenavistita,” Laurel, Maryland, U.S. The methodology is qualitative, based on interviews and participant observation. The findings allow us to argue that the migratory experience forces them to loosen their identity boundaries inward the ethnic group to reconstitute themselves, survive away, and maintain their Mexican mestizo status. Resulting in the formation of territorial enclaves where they identified against those who label them as illegal, this being the way to defend themselves in a racialized society. This work contributes empirically to migration studies with the case of Chiapanecos mestizos. Although we conclude that the enclave is for them a refuge area, little can be said about other experiences of migrants from Chiapas around ethnicity and the blend of cultures.

Keywords: interethnic relations; transnational network; ethnic enclave; Buenavistita; Mexico

El objetivo de este artículo es demostrar la estrategia de adaptación sociocultural de un grupo de migrantes mestizos chiapanecos residentes en Buenavistita, Laurel, Maryland, EE. UU. La metodología es cualitativa, basada en entrevistas y observación participante. A partir de los hallazgos argumentamos que la experiencia migratoria les obliga a flexibilizar sus fronteras identitarias hacia adentro, a fin de reconstituir el nosotros, sobrevivir a la distancia, y mantener el estatus de mestizos mexicanos. Resultado de esto es la formación de un enclave territorial, en donde se contienen identitariamente frente a quienes les etiquetan como ilegales, siendo éste el escudo de defensa en una sociedad racializada. El trabajo aporta empíricamente a los estudios de migración el caso de los mestizos chiapanecos. Aunque concluimos que el enclave es para ellos una zona de refugio, poco podemos decir sobre otras experiencias de chiapanecos migrantes en torno a la etnicidad y el mestizaje.

Palabras clave: relaciones interétnicas; red transnacional; enclave étnico; Buenavistita; México

INTRODUCTION

This article has as a goal to show that an ethnic enclave is a strategical response to the socio- spatial segregation experienced by a group of mestizo migrants from Chiapas in the United States. Such enclave is territorially defined and limited by means of spatial appropriation, cultural adaption and the social reproduction of a group of people alien to the receiving society (Luque, 2004). The creation of this enclave allows migrants to settle down, interact and integrate into the American society with help from transnational networks in order to recreate their ethnic identity and cope with racism, discrimination and struggle for the right to a place in a context of international irregular migration (Basch, Glick Schiller, & Szanton Blanc, 1994).

Migrants from Buenavista (or buenavistecos, i.e., people from Buenavista ejido, in the Municipality of Villa Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico) are flexible workers who lack employment guarantees, live in overcrowded and precarious conditions, while at once, they face exclusion, class, race and ethnic struggles. We found that in order to resist, migrants adapt in a sociocultural manner that symbolically maintain their identity supports, which in Mexico provided them with advantageous positions, for example, in this case, being Mexican mestizos and rancheros (peasants/ranchers).

In Chiapas, the second state with the largest indigenous population in the country, the miscegenation entails ethnicity on the basis of prerogatives regarding the indigenous population, considered inferior or of lower social class (Gall, 1999). We stated that the mestizo migrants from Chiapas lose the ethnic privileges provided by a status system that in their country-of-origin places them atop the social scale due to their skin color, less brown than that of other indigenous peoples, they speak Spanish and their better social stratum. These are advantages they miss when they migrate to the US because in this place, they are equaled to the millions of migrants owing to their undocumented condition and with millions of Latin Americans who undergo a re-ethnization process (De Genova, 2008).

Even if identity is relational and plastic, there is a grip assimilated in the place of origin that guides the ways of doing and thinking individually and collectively (Giménez, 2001). In order to reproduce elements of such ethnic identity in the distance, people from Buenavista resort to a delimited territorial settlement, which concentrates migrant people from the same ejido, Buenavista, in the municipality of Villa Corzo, in the Frailescana Region of the state of Chiapas. In order to have cultural continuity in the US, people from Buenavista reproduce the most important festivities in their place of origin, still talk with the idioms, accent and slang of the Frailescana Region. They also maintain cultural practices such as food, religiousness and ranchero attires, which help these migrants adapt to the American society, importing from their town local products that also give them social status in the group in Maryland.

Outwardly, migrants from Buenavista interact with other ethnic-racial groups with various migration status and nationalities, regularly their interaction is confrontational and competitive (Giménez, 2001). The above forces these mestizo migrants from Chiapas to unfold identity contention strategies via the ethnic enclave, whereby they exclude and typify other migrants, for example African-Americans, Salvadorans, and even white Americans. The first because they are the immediate alterity in the receiving city, they envy some of their rights, which they are not entitled to in the US, mainly because they consider African- Americans to have lower ethnic rank, for they are black. The Salvadorans are envied due to their access to spaces and opportunities, as they are refugees and enjoy better social position because they have documents and are able to access better labor opportunities than migrants from Buenavista. They are resentful toward Americans, since they are considered to represent the history of the former Mexican territory, American at present, and because they are the population with the best conditions of life and are a wealthier social class.

Even if the ethnic enclave created by migrants from Buenavista is not supported on local and/or autonomous economy as suggested by the literature (Portes, Guarnizo, & Haller, 2002; Riesco-Sanz, 2010), it does have a particular socio-spatial logic and is geographically and territorially defined by the BosWash corridor, thus named by Khan and Wiener (1967) (a portmanteau of the cities of Boston and Washington D. C.), which encompasses some of the most important cities in the American northeast, among them Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington D.C. It also operates with cultural boundaries that have become flexible and extend their hometown (Luque, 2004). It is also true that they do not mirror the Buenavista ejido, in Chiapas, Mexico, as such, it does however adapt cultural elements and goods that serve them to reproduce their identity far in the distance and settle down with a logic based on their hometown. For Buenavista migrants, it is necessary to learn to navigate the hierarchical and excluding American social multicultural structure, cemented on ethnic -racial-labor logic. Due to the foregoing, mestizos from Chiapas interact and compete for job posts, housing, education, health care and recreation with other migrants and immigrants, which is not simple.

Our approach, using the transnational migration paradigm, is build from the creation and functions of ethnic enclaves as strategies of cultural repetition and identity contention of dual and transnational nature. To analyze our field findings, we particularly focus on the works by Levitt, De Wind and Vertovec (2003) and Velasco (1998) because these authors dealt with the analysis of cultural and identity changes, but mainly with the subjects’ resistances in order to carry on belonging to their place of origin outside of it, and from their experience in international migration emphasize their territorial rooting and ethnic belonging by means of transnational networks and social links that update their belonging.

Faist (2005), Luque (2004) and Portes (2000) studied other cases of territorial enclaves of immigrants who develop cultural and social capabilities to integrate into other places. Portes (2000) distinguishes mainly that the activities require usual social links that go beyond the borders to integrate. We notice that this constantly takes place in the Buenavistita [Little Buenavista] enclave: the speech, attires, festivities for Our Lady of Guadalupe and Santa Muerte, foods, and especially parenthood and godparenthood; identity elements around the ejido, region and the mestizo-rachero ethnicity of the place of origin.

The migration experience affects in various manners to the international migrant groups according to their cohesion, migratory background (for example that of Mixtecos from Oaxaca and ranchers from Michoacán) and ethnic condition. For the enclave under study, the consistency and intensity of movements, transactions and relationships between nations, even if they operate in a bifocal manner, are enclosed into a physical territory and culturally alien, in this case located in the BosWash corridor.

In this article we are interested in demonstrating that an ethnic enclave is the answer of a mestizo migrant group to face a situation in which the privileges they had in their place of origin vanish after arriving in the destination. By doing so, we intend to contribute to the reflection on the differentiated processes that non-indigenous migrants from Chiapas face, exposing the case of mestizos from Fraislescana Region in Chiapas, identified as mestizos and rancheros. Firstly, we approach international migration from Chiapas focusing on the case of Buenavista; we resort to nationalism as analytical standpoint to discuss our findings regarding this ethnic enclave and wield it as a strategy for identity adaption. Then, from the approach of collective identities, we deal with the adaption experience by individuals from Buenavista when they migrate.

We start off from the (social) imaginary on the homeland, historically and socially involving their belonging to the Frailescana Region and Buenavista ejido, though strongly differentiated inwardly by social class and kinship. We are interested in the way such We becomes the migration because we find that identifications based on the place of origin dilute out of the need for cohesion in the receiving place. The social class and ancestry differentiators that used to provide migrants with a high social status does not work in the same manner in the receiving ethnic enclave; conversely, the union of various social classes serves as cultural bonds and reproduction of their belonging to the territory of origin. Outside the enclave such bonds strengthen its barriers, shielding them from the Others, that is to say, against those groups that create local identities and that discriminate them because they have better social positions and regularly with more advantages than them.

METHODOLOGY, RESULTS AND LIMITATIONS

The methodology was qualitative and fieldwork focused on two places. On the one side, Buenavista, place of origin of the migrants, located in the Frailesca Region of Chiapas, México and “Buenavistita”, the receiving place, in Laurel, Prince George, Maryland, US. In 2016, we carried out fieldwork on the place of origin, we traced the indications of migration in the history of the town and found the pioneers of migration in the Frailescana Region. We defined the routes, chains and networks created by these migrants. In 2017, we carried fieldwork in Maryland with Buenavista natives established in the Buenavistita enclave in the United States. The research techniques were participant observation, in labor, familial and leisure spaces, and in-depth interviews held in private and domestic places or where they felt most at ease. We are guided by the production of their stories and their potentiality, which helped us reconstruct individual and collective biographies of migrants (Berteaux, 2005). Later on, we identified the establishment of Buenavistita enclave and understood its function as a strategy for sociocultural adaption by means of the exclusion of others.

We found that the territorial settlement of people from Buenavista is defined by group interactions of these mestizo migrants from the Frailescana Region in the city of Laurel, Prince George County, Maryland. Right in the middle of BosWash corridor, we recorded the presence of 200 individuals from Buenavista in two areas, Village Square North (70) and The Pines (130). We held seventeen in-depth interviews with 11 men and six women of them, with a mean age of 45 years and also 12 years on average living there. Moreover, we observed the labor spaces where they develop, partook of their activities and conversed informally with them; this enabled us to analyze the functioning of their enclave and the definition of symbolical borders regarding the others, we were able to account for the antagonistic relationship with other migrants and the locals. However, this article did not deepen into the respondents’ expectations to extend their stay without documents or else return to Buenavista, Chiapas. The tendency to remain in the US was marked by a precarious past in their hometowns, without considering the conditions of precariousness entailed by living without documents in this country.

The most important finding was the definition and denomination of the ethnic enclave, a common space where migrants contain, negotiate or reconfigure their identities within the context of their undocumented migrant and mestizo condition. The enclave works as a space where the group dilutes or makes their own identity categories flexible, allowing the integration and coexistence of various hierarchies and social class groups among the individuals from Buenavista. One of the most novel examples was the matrimonial alliance of one woman from Buenavista with an indigenous individual from Chenalhó, Chiapas; an uncommon case, though likely. Another novelty is the union of people from opposing groups in the hierarchy, something uncommon in the fabric of Buenavista ejido. This gives an account of the permissibility to carry on reproducing as people from Buenavista, integrating themselves or forging alliances so that the ethnic mestizo identity lasts and mainly to recreate the name of the territory in the distance.

BACKGROUND: INTERNATIONAL MIGRATIONS AND MIGRATION FROM CHIAPAS

In migration studies, the analytical line on integration or sociocultural adaption is a well- developed one by the American, Canadian and European academy (Portes, 2000; García, 2006; Torres and Anguiano, 2016), which challenges us because we believe that the complexity inherent to migration may be approached resorting to the impact on subjectivities and the role networks have in the migrants’ labor and social insertion in a new city. The transnational approach, whose proposal supported on subjects and their unfolding or actions in the context of dual referential frameworks (Faist, 2005) is a fertile analytical way to understand responses or resilience capacity the subjects have when they face new social and cultural spaces of which they are fully unaware. This approach puts forward that ‘new’ forms of being and belonging must transcend the borders (Levitt & Glick-Schiller, 2004) and being at least bifocal with a view to securing their everydayness in the receiving place, giving their social identities and differences feedback, securing interpersonal bonds, intergroup chains and collective networks to adapt and integrate into the new situation in the recipient place. This way, the strength, influence and impact are established by the migrants in two directions (in a round trip) to give an account of continuously being in the distance, that is to say, from the receiving to the departure places and vice versa. From the assumption that migrants “are located within social fields at multiple degrees and multiple places, which go from those who move to those who stay” (Levitt & Glick-Schiller, 2004, p. 61), reproducing identity bonds that join them, and which we state, strengthen the experience of migration creating ethnic enclaves that not only facilitate adaption or survival processes, but they end up establishing borders within which they exclude others via discourses and practices regarding otherness and selfhood.

Even if the concept of ethnic enclave refers to a particular settlement, it is also the result of networks and chains in which settled migrants provide new migrants with social capital, creating a social base for the interchange of tangible and intangible assets for new migrants that would reduce the costs of transport and settlement, and would also reinforce security at arrival and improve the integration conditions in the receiving society (Massey & Aysa, 2007). Daily routines are based on the vital logic in simultaneity with the events that occur in the recipient space and their homeland for they purposefully serve to maintain the ethnic hub in an alien and appropriated space. To do so, the information disseminated among the migrants regularly ranges from basic –employment, health, housing and opportunities–, to the intangible, which feeds the imaginary of the receiving community: people, families, barrio, interactions of the homeland, gossip or small talk that update the everyday life in the ejido. The ethnic identity in the country of origin is reinforced by means of relatives, compadres, neighbors and acquaintances with the same ‘ethnic rank’ as those who accredit such identity. The ethnic enclave established by Mexican mestizo migrants from Chiapas settled in the BosWash corridor is a response to the loss of privileges inherent to miscegenation in Mexico. Mestizo migrants from Chiapas establish their ethnic enclave as an identity contention strategy before the others, and in this way, as a means of cultural adaption in the arrival places.

International migration from Chiapas entered into the migration map in the last decades of the XX century and the first of XXI (Jáuregui & Ávila, 2007). According to Banxico (2020), in the first half of 2020, Chiapas was among the ten states with the most remittance sending. Economic and socio-environmental processes, particularly the rural crisis, hurricanes Mitch and Stan, and the 1994 Zapatista uprising added to the departure of people from Chiapas toward the US (Villafuerte & García, 2006; López, Sovilla & Escobar, 2009). Martínez (2014) explains that the social conditions of the time in the state followed a developmental delay regarding the rest of the country. In this sense, according to García de León (1997), we understand that, while other regions and states of the country experimented modernization due to the agrarian allotment under President Cárdenas and the later agricultural modernization, in Chiapas latifundia and semi-feudal economic relationships prevailed, hindering the modernization and generating a society more similar to that of XIX- century Mexico. For Martínez (2014), it was when Chiapas experienced a transformation in the social structure that migration occurred. By going from a semi-feudal structure to land allotment, porters and baldíos (people without occupation nor profession) had the chance to access land, which gave them the possibility to relate with external agents that did not exist in the previous structure, namely the agrarian bureaucracy represented by technicians, engineers, et cetera. This new universe enabled them to find out about other worlds outside the fields; this way, the earliest domestic and international migrations took place.

Rus and Rus (2013) document the pioneering experiences of indigenous migrants in the US and the impacts on Chamula localities in Los Altos de Chiapas, on the community’s economy, family roles, marriages, mental health from the absence of migrants, remittances and their return. Mercado-Mondragón (2008) accounts for the changes in the identity of migrants from Zinacantán (Chiapas). Aquino Moreschi (2010) follows the route of Tojolabal youths hired in seasonal jobs in the US, analyzing the way their constant residential changes make it impossible for them to create communities or networks; while Cruz-Salazar (2015) approaches the role of the definition of new life styles among Tzotzil migrant youths. These research works help us understand the migration experience of indigenous migrants v. non- indigenous migrants from Buenavista, when the latter suffer discrimination because of the American ethnic-racial prejudices that undermine their identity, making them look for shelter in strongholds of ethnic-social-economic nature before their departure and which are later labeled in the US as Latin Americans, with the full pejorative load it implies. “Being just another Mexican”, which hurts their pride in their mestizo identity, makes them feel the decrease in the social scale where once they were held high because they lived in a highly productive mestizo region in Chiapas.

Unlike Tojolabal, Tzeltal and Tzotzil indigenous migrants (Aquino Moreschi, 2010; Cruz-Salazar, 2015; Rus & Rus, 2013), mestizos from Buenavista did not have to migrate domestically until 2000, neither were they discriminated in Chiapas or in the country for two centuries. On the contrary, they always enjoyed ethnic-economic and regional privileges due to their livestock activities developed in the Frailesca Region and the ranchero culture that arose from such activities. This way, in the identity of these individuals from the Frailesca Region, miscegenation was an important axis for their self-identification as renowned individuals from Chiapas, some with ancestry, some others only from the fringes of the ejido, however all of them with a different status, that is, greater social recognition than the rest of individuals from Chiapas. At the base of the pyramid of ethnic identities in traditional society are indigenous people, above them we find mestizo identifies and at the top, mestizos with last names from the Frailesca Region: Grajales, Coutiño, Solís, Zuarth, among others. To grasp the weight of surnames in this region, it is necessary to revise the works by García de León (1991, 1997, 2002).

Once in the United States, re-ethnization for migrant individuals from Buenavista takes place from the outside, that it to say, in the recipient community, in this case, the American Anglo-Saxon, popularly known as the white community. They turn all the Latin American migrants into the representation of an underrated and much needed identity, the Hispanic, which includes the Mexican. The representation of Mexicans in the US dates back to the late XIX century, it depicts a poor and unskilled worker suitable for hard work and follow orders. The pejorative load that identifies and associates them to the dirty and the uncivilized is a social-class distinction that rooted during the time of the Bracero Program (1942-1964), even though it later changed into ethnic differentiation. The image of workers covered in soot added to the creation of a Mexican3 phenotype, distinctive due to skin and eye color, and black hair; a population that ever since has carried a series of jobs that the white population considers to have the least social prestige, for instance, janitors, gardeners, builders, dishwashers, among others. De Genova (2008) states that this is a representation created by the American culture to name and identify the immediate others, ‘the Mexican immigrants’. It is not relevant whether they are mestizos or indigenous, as soon as they arrive in an US city, the American eyes racialize them (Zavella, 2011) because they are identified as part of the Mexican transnationality that crosses the Mexico-US border. Therefore, the Mexican low, dirty class, peasant or rural, that does the jobs with the lowest ranks in the US (Gomberg-Muñoz, 2011). This representation in the US ignores the cultural diversity of Mexico and creates a particular space and treatment for them, as the Spaniard colonialization did, obviating the Mexican cultural diversity back then, calling all pre- Columbian cultures “indigenous”.

The contribution of the present work is the analysis of such difference, as it approaches the way mestizo migrants from Chiapas, in this case from Buenavista in the Frailescana Region, face migration resorting to the ethnic enclave in a multi-situated social space.

DEVELOPMENT AND DISCUSSION

Homeland, the network and the enclave: the sociocultural adaption strategy in the migration process, a contention to symbolically preserve mestizo privileges.

Buenavista, the homeland of ejido-holder mestizos

Buenavista is an ejido located in the municipality of Villa Corzo in the region called La Frailesca, in the state of Chiapas. It was established as an ejido in 1936 by means of the agrarian policy of President Cárdenas. Over the XIX century and the first third of XX, a large part of the population who lived in present-day Buenavista lived under the plantation system.

Plantations were agricultural production units, they had a large house with barns to store production, rustic housing for porters and other workers (baldíos), plus chapels, where festivities for the patron saint of the plantation were held. Porters were the low social class, which comprises individuals subjected to the system via their debts. For their part, the rest of workers, the baldíos, were free individuals who hired a plot of land they paid for as days in service of the plantation holder. This way, in basic terms, social classes were plantation owners, baldíos and porters.

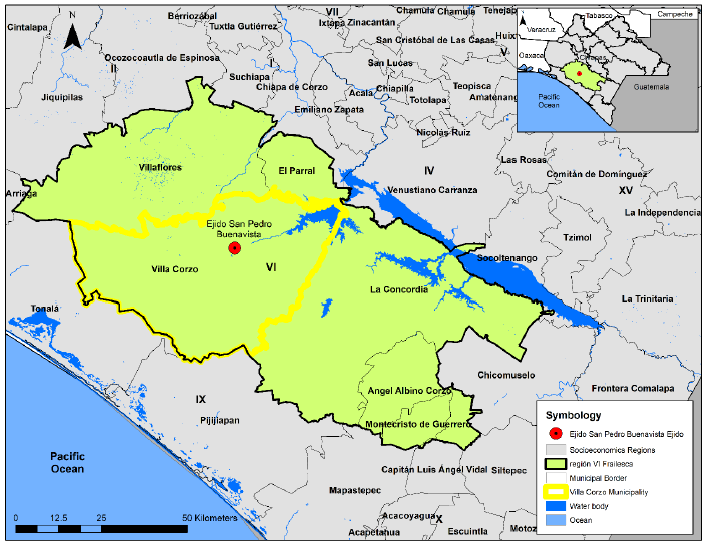

Source: Departamento Observación y Estudio de la Tierra, la Atmósfera y el Océano, Grupo Académico Ecología, Paisaje y Sustentabilidad, ECOSUR.

Map 1. Origin of the respondents: Frailesca Region and Ejido Buenavista, Chiapas, Mexico

Once the allotment of the land was carried out, everyday life changed the structures and introduced a new pattern. The main changes took place in production. Livestock turned into maize and bean cultivations, which were carried out by workers in the plantations, but they were devoted to address the population needs. These produce became the most used for family support and also as the main income source, under a schema of agriculture subordinated to a development model fostered by the State.

The change in the model entailed one in relation to the structure of labor relationships. The plantation as an economic unit depended on the work of porters and baldíos, who lived in servitude without receiving any income, but the owner gave them what was barely necessary to survive, or did so with what they were able to harvest in the small plots of land they were allotted (Toledo, 2013). The state development model fostered the ejido and destroyed the labor relations that supported the plantations, which produced a peasant population, equally subjected to the state, who sold its labor force. The children of ejido owners, or neighbors without land, also opted for becoming salaried day workers.

This change had effects on other aspects of the community structure, making room for distinctions of class between owners of ejidos and those who were not, i.e., residents and day laborers. Ever since the constitution of the ejido, social classes were defined by a) land tenancy, b) belonging to the ejido (where land was shared), and c) agricultural activities. Owners of ejidos were the highest social class, whereas the lowest, merchants and aliens (from outside the ejido), where indigenous people residing in Los Altos de Chiapas were found. Adding to this type of differentiation, the plantation system left a mark: the issue of hierarchies. Surnames such as Grajales, Ruiz, Coutiño, Solís or Zuarth are linked to the plantation owner class, thereby, every individual from the Frailesca Region or from Buenavista who has these last names belong to a hierarchy above other people from this region.

The social, economic and identity configuration of Buenavista changed as well because of migration. In this sense, we identify two moments in the international migration from Buenavista. The first is the participation of individuals from Buenavista in the Bracero Program in 1955; then, a second wave opens with undocumented migration from Buenavista as of 1996, a moment that concurs with the structural conditions described above.4 Migration dragged rancheros, owners of ejidos, residents and the various hierarchical components. These differences in class and hierarchy between people from Buenavista reconfigured over the process of migration, which allowed this group to create a transnational network and an ethnic enclave as a strategy of identity contention before other ethnic groups in the US.

The transnational Buenavista network in Maryland

Nicolás Guillermo, who left in 1982 with another migrant from Villaflores, first to California and then to Washington, is considered the forerunner of migration from Buenavista. Nicolás invited a nephew to travel to the state of Washington in 1987, with Aldape, who would later work in a fishing boat of an English company, where three years after arriving he suffered an accident on the way to Alaska. After months in a coma and after his recovery he sued the company aided by an attorney and won the case. In 1995, Aldape returned to Buenavista Ejido with money, thus he sent a powerful message and image of success about international migration. His return generated expectations between acquaintances and classmates, as he returned in a new car and built an American-style house, making the people from Buenavista created imaginaries in which migration acquired centrality as an opportunity for economic growth and social mobility. Besides, the representations produced on the migrants from Buenavista, Aldape disseminated the information, providing possible migrants with the social capital he had acquired during his stay in the United States.

In 1997, there were four individuals from Buenavista in Maryland, US, who served as attraction poles for others, enabling the formation of migration chains. According to Gaete and Rodríguez (2010), migratory chains are a sort of first phase in the development of networks and are defined as “informal social networks, composed of extended family, friends and neighbors who, in the postindustrial society, are still an important source of fellowship, mutual support and help” (Requena, 1991, quoted by Gaete & Rodríguez, p. 700). In any case, information regarding these migration chains from Buenavista favored the increase of migrants from Buenavista.

The earliest chains from Buenavista were commonly created by men in a range between 25 and 32 years of age, who had been left out from schooling opportunities and which because of the agrarian demise were excluded from the labor market in Buenavista. These migrants were fundamental to accelerate the migration process in Buenavista and invite relatives, friends and acquaintances, whom they provided with lodging, food and support for their insertion in the labor market in Maryland.

By the end of 1998, Hurricane Mitch damaged the watering dam that enabled the owners of ejidos and producers to harvest twice a year, deepening the agricultural crisis. By then, there were already about 25 individuals from Buenavista in the periphery of Washington D.C., in particular in the city of Greenbelt, in Prince George County. The arrival of individuals from Buenavista to Greenbelt apartments made the migrants from Buenavista scatter, for as more people arrived new groups that were looking for their own spaces appeared, which created new chains that moved as they learned about the place, the jobs and the new members. In spite of the dispersion of the chains, migrants from Buenavista had the necessary support to find housing, food and employment. From 2003 to 2005, 832 individuals from Buenavista migrated to Maryland, almost 10 percent of the total population of the ejido in Chiapas, 8 800 inhabitants (J. Núñez, field diary, May 7, 2016). In that moment, chains turned into a migration network.

In 2003, the transnational network created by individuals from Buenavista was composed mainly of people from the ejido who lived in such places, that is to say, in ejido Buenavista (Mexico) and in Buenavistita (Village Square North and The Pines, Laurel, Maryland, US), and interchanged communication and constant support. Such network has a solid social capital organized in communication and flow circuits through which material and immaterial goods flow. The transnational network from Buenavista is composed of relatives, neighbors, godparents and countrymen who mainly reside in Buenavistita, and other non-migrants who live in the Mexican ejido, who nourish and use the supportive networks as strategies in the migration process for their incorporation with greater certainty, cost reductions, as well as monopolizing opportunities and benefits (Massey & Aysa, 2007).

In 2005, Martita traveled with one of her brothers to Laurel, where her boyfriend lived, who had arrived two years before. He paid for her travel expenses and helped her to obtain her “chueca” (fake work permit), in addition to lodging and food. After her arrival theymmade a home (J. Núñez, field diary, July 3, 2017). Out of love, solidarity, affection, necessity or integration, these migrants create and share a transnational worldview as they commit to the ethnic group and their homeland via meanings, memories, future expectations, language and collective representations.

At local level, the group from Buenavista reproduces by means of the updating of their membership in a host city (the way they speak, eat and think; certain aspects regarding the homeland) and their commitment to the place of origin through constant communication or money or in-kind remittances; this way, the transnational network remains because of reciprocity. Ethnic identity is updated with collective memory, the identification of the territory and the relative integration into the receiving community in Maryland (Basch, Glick Schiller and Szanton Blanc, 1994). Transnational practices are the main actions to keep these networks alive, which generally become tangible with economic, sociocultural and symbolic remittances (gifts, virtual presence in baptisms, first communions, XV años, and weddings, among others).

We receive cheese and meat from Buenavista. Two years ago, in December, I sent a package with Fernando for my son who’s there; my son likes basketball: official shirts, Nike sneakers, perfumes, other clothing, sports pants, three pairs of shoes, a pair of Nike and the others cheaper, and things for my mom; not new clothes, but wearable, a computer. But we got robbed of the best of this, they took caps –which are expensive–, shirts which cost me 75 each, about 1500 pesos and 300 USD, and when things arrived, they were in disorder. I had enough of that and do not send anything anymore with him, I prefer to send them by [postal] mail and they arrive well (Imelda, personal communication, June 12, 2017).

Right now, I am waiting for some football boots to fit me, a pair of Concord, here you can’t find them, because there [in Buenavista] that was not enough to buy them, because they cost about 500 pesos and I didn’t have them, then… my brother, I phoned him time ago “brother, take a photo of a pair of Pirma Brasil, a couple of Manríquez, and a pair of Concord; the most expensive I told him, now I can afford them” and he said, “the most expensive is about 1000 pesos”, “oh well those I want, I can afford them”. From here, it is sent with Fernández, but my brother is going to send it to me in Villaflores, by parcel service, because once I had meat brought, my dried meat from my grandmother’s, because I know she does it really tasty, it came with worms. Delicious is my grandma’s meat, tascalate, cheese. Sometimes, two or three medicines for worms, I can’t find them here (Ernesto, personal communication, July 29, 2017).

The use of ICTs and social media has made it possible to revitalize these practices that individuals from Buenavista nourish day after day from the social hub they have created in Maryland to the ejido of origin. The networks develop by means of the active presence of their members and their practices (Faist, 2005; Levitt, DeWind and Vertovec, 2003).

Buenavistita, an ethnic enclave in Maryland

The Washington D.C.-Baltimore corridor is at the southern end of BosWash corridor and it comprises the cities above, the capital city of the US and the most populated in Maryland, respectively, and the conurbation between them. The corridor has a diverse population, in which Hispanic are prominent in numbers and economically.

Source: authors own elaboration.

Map 2. Destination of the respondents: WashBalt corridor and area of the Buenavista enclave

Out of the total of Latin Americans, Salvadorans account for most in this state, about 123 789, that is, 26.3 percent, Mexicans are next (18.7%), then Puerto Ricans (9%), Guatemalans (7.3%), Hondurans (4.4%), Peruvians (3.9%), Dominicans (3.2%), Colombians (2.8%), and Cubans (2.2%) (Department of Health and Mental Hygiene of Maryland, 2013).

Migrants from Buenavista settle in the Washington D.C-Baltimore corridor, particularly in the periphery of Washington, in the Prince George and Anne Arundel counties, where they live in apartment buildings in Laurel city, in our case The Pines and Village Square North apartments ( Table 1 offers some data from Buenavista migrants).

Table 1. Sociodemographic data

| Name | Sex / age | Residence years |

Schooling | Post | Remittances / month |

Status in the ejido |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axel | M/41 | 14 | High school | Employee | Variable $400.00 |

High |

| Rafa | M/42 | 14 | High school. | Employee | Variable $200.00 |

High |

| Alma R | W/36 | 12 | Incomplete/ undergrad |

Employee | n/d | Average |

| Fabian | M/40 | 4 | High school | Employee | $1 400.00 | Low |

| LR | M/64 | 13 | Elementary | Employee | $1 500.00 | Low |

| JLNM | M/39 | 14 | High school /College |

Gerente | $800.00 | High |

| Coli | M/50 | 19 | High school | Employee | n/d | High |

| Imelda | W/40 | 16 | Technician | Employee | $600.00 | Muy Low |

| Ernesto | M/33 | 14 | High school | Employee | $200.00 | Average |

| JARS | M/44 | 12 | High school | Employee | $500.00 | High |

| Lucre | W/48 | 15 | Elementary | Employee | $600.00 | Very Low |

| LNM | M/37 | 16 | Secondary | Manager | $300.00 | Low |

| Ani | W/36 | 14 | High school | Employee | $200.00 | Low |

| ST | W/62 | 10 | Elementary | Owner (taco stall) |

$1 500.00 | Low |

| SN | M/63 | 12 | Elementary | Employee | $1 300.00 | High |

| Pillo | M/58 | 16 | High school | Owner (parcel service) |

n/d | High |

| Irlanda | W/37 | 13 | Incomplete/ undergrad |

Employee | $2 500.00 | High |

Source: own elaboration based on interviews held in 2017.

The experience of migration at the destination places includes diversity and ethnic reordering different from those in the place of origin. The miscegenation in the destination lacks social recognition and blurs before the absence of documents of the migrants from Buenavista, which places those previously privileged in precariousness and invisibility. In the face of this, the resilient response is to create enclaves in which they are able to contain their collective identities, symbolically represented by belonging to the ejido. Such enclaves, as previously expressed, are supported by means of migrants’ networks and chains developed over the years.

The ethnic enclave allows visualizing the migrants from Buenavista by reconfiguring their culture and anchoring to their collective memory to reproduce their homeland in new places, such as Giménez (2001) affirms and Velasco (1998) demonstrates, from a transnational approach, for which the territory comprises nations and becomes the space where national states do not hold identities. In such manner that, depending on their place of origin and the role taken in the receiving place, migrants may be mestizos and rancheros and also urban Latin Americans in Maryland at once (Levitt & Glick-Schiller, 2004).

I remember the fair, montadas de Judas in Holy Week, the charreadas, go up La Cruz Hill, in May, the Piedrona (huge rock) and the dam. Now, they post photos on Facebook, it doesn’t even look like the river I remember, totally dry it is (Irlanda, personal communication, July 9, 2017).

That is to say, “transnational migrations are noticeable because of their capacity to build new cultural configurations which cannot be easily attributed to a single national territory” (Velasco, 1998, p. 106). Here, collective memory is the key for the migrants from Buenavista to build the simultaneity which keeps them standing on a here, whereas many of their thoughts, feelings and actions are aimed at a there.

My little children were born here, but it is as though they knew Buenavista. I tell the big one about the river, of La Piedrona, of the minibus my father drove, there boys attended high school in Villaflores, I tell him about my brothers, Mario and the way he studied as a grown-up. Sometimes, without a word, my little child tells me. “Hey, mommy! As in Buenavista!”, Or he asks me, “when are we going?”. Every time we meet the topic is Buenavista, “do you remember this and that?” it isn’t the same, but it’s a way to remember, being far away only the memories; I hope we return one day, but differently, with the opportunity to legalize our status (Alma Rosa, personal communication, July 22, 2017).

The impossibility to return to the homeland due to their irregular migration status shows the interests in keeping the life style that their labor income in the US allows them to lead, creating a simultaneity of transnational order, which is paradoxical, for it implies being at two different nations and interacting with two dissimilar national identities: the mestizo and the Latin American or Hispanic in the US, both are hetero-imposed, though the mestizo identity is indeed assumed. For individuals from Buenavista, their identity has to do with territorial, linguistic and cultural supports recreated over the migration (Giménez, 2009). The enclave enables them to reterritorialize themselves in Maryland, recreating Buenavista, a place of memories about the ejido in the Frailescana Region in Chiapas, and which draws ejido members with cultural and indigenous-identity repertoires adapted to be recreated.

…Doña Margarita throws the party of the virgin on 12 of December, the same we throw in Buenavista. She invites all the plebe [the plebs]. We eat tamales, barbacoa, cochito horneado, Goodness! As in Buenavista. We just talk about Buenavista, the gossip, once the plebs are drunk, just dancing, as they say: una vez al año no hace daño [Once a year, it harms no one]. There you find what goes on in Buenavista, because when you speak to your family you only hear how they are, what they do, what they will buy or need. Thing is, when the plebs get together gossip from Buenavista comes out, you learn about everyone here… about the truth… we are just kidding (Fabián, personal communication, May 17, 2017).

Capable of dealing with simultaneity (Velasco, 1998), these subjects reconstruct their culture and memory. The communication and the secrets inside the enclave are known for the entire network and travel at significant speed:

The problems of people from Buenavista are two; drinking, a lot of them get on a drinking binge and miss job, or arrive drunk and got fired. The other is what they do here soon enough becomes gossip in Buenavista, news travels fast, if they meet here, immediately it is known there, when Reneir Ramos, aka El Ojito, died on a drinking binge, he had an accident, he was with others from Buenavista. I talked to my mother in Buenavista and she told me, how is that possible? You learn about the events here phoning Buenavista (Pillo, personal communication, July 14, 2017).

Once inside the enclave, this unfolds in a multidimensional manner. On the one side, as the common place for migrants from Buenavista to reproduce their language or reconstruct identity elements that enable them to continue belonging and recreating their territory (Velasco, 1998); while on the other side, as shield against the immediate others, e.g., Salvadorans and African-Americans.

As a common place, being a member of the enclave allows enjoying privileges, which aim at the remembrance of the homeland via flavors, odors, sounds and images. This way, individuals from Buenavista have stuff that belongs to their homeland delivered and once they have such cultural assets (García Canclini, 1993), they dress in the Buenavista fashion, they party as they do in the ejido, they cook dishes with traditional ingredients and drink thinking of their childhood and youth. The enclave also works as a filter to dilute the class and hierarchy system of people from Buenavista, as it enables likening members of a related wealthy class with other of low class, as it is evinced in the following testimony:

My children’s father is from Buenavista; his parents sold empanadas and tacos in Buenavista, in front of my granny’s business. I saw him there, but we didn’t even greet. Here you see people from Buenavista you didn’t even know or didn’t get along with, and you make friends with them here because there are a lot of people from Buenavista. I met him here and it is fun that his last name is Tamayo, I wasn’t able to imagine I would relate to someone from that family (Irlanda, personal communication, June 12, 2017).

This way, the Buenavista ethnic enclave dilutes social class differences to exclude those who were not born there or do not have a common history, and which besides are part of immediate antagonistic identities such as African-Americans and non-Mexican Latin Americans. Individuals from Buenavista everyday interact with both groups in labor spaces and they exclude them as they represent labor competition. They see African-Americans as the fortunate, as they can afford not to work and exercise violence against Latin American immigrants, as documented by Cruz-Salazar (2015) researching on rivalries and rites of passage that new indigenous migrants from Chiapas experience from the African-American population; this way, their relation with them is highly tense and confronted. They have categorized each other according to their phenotype, and among individuals from Buenavista a series of stigmata have been unfolded around the brown skin color.

The dark skinned will never get along with Latinos. They are drunkards and druggies, conflictive, they meet you on the street and they ask for change for a cigarette (Coli, personal communication, June 12, 2017).

Since miscegenation, as a distinctive element of class-ethnicity, transforms as it encounters referents different from those in the homeland; these referents make room for the racial issue. The new referents are phenotype, race, ethnicity and behavior; this way, by and large, the ethnic groups they interact with in their everyday life represent alterity for them. They turn the Other into a stigmatized subject, deviated, demonized, inferiorized for representing threat and superiority. Black people are considered drunkards, drug addicts, conflictive, bad or beggars by people from Buenavista. From these categories, they contrast them with other ethnic groups such as the Muslims, which they consider “respectful, quiet”, finding that the former unlike the latter are rude, noisy, dirty and lazy as expressed by Ani:

There are people from everywhere in the apartments; many of them use their veils, Muslim a quiet people, don’t mess around. The dark skinned are different because they’re rude, noisy, there were a lot of them in the apartments, but these Muslims started arriving and they started to leave, very few remain, way better! Because they littered a lot. At work, there are many dark skinned, if it were for them, they would be sitting all day long (Ani, personal communication, July 7, 2017).

Unlike the previous case, for individuals from Buenavista, Latin American superiority is presented by Salvadorans, a majority Hispanic group with documents in Maryland. To refer to them, people from Buenavista generally use pejorative terms:

…Salvadorans are snobby because they have permit to be here, they hate us because they say they suffer a lot when they travel over Mexico, they are robbed, women raped, unfortunately there are lots of bad people (Axel, personal communication, May 23, 2017).

Salvadorans are the worst, they discriminate, they feel Americans, when a Salvadoran already stepped on American soil, they feel the best, when they remember they passed three borders, plus the Mexican, which is more complicated, they hate the Mexicans the most, particularly Chiapas they say, as it is one of the borders that they mentioned the most (Coli, personal communication, June 12, 2017).

The testimonies above refer to the status of temporary protection Salvadorans enjoy in the US. In their labor interactions difficulties with them are constant:

[…] if you start work where most are Salvadorans, they start gossiping, laughing at you, they are sort of dumb, this is why gringos prefer Mexican workers (Rafa, personal communication, July 27, 2017).

Salvadorans are good at work, but they are very rasquitas [quarrelsome], when two work together, they only talk bad about people, particularly about Mexicans, not that they are the best at work, but they make an effort, the usual thing, but if you compare them with one from Buenavista, they are no good (Lucre, personal communication, July 19, 2017).

As noticed, the power-inequality axes that are significant in the place of origin modify in the context of the receiving place, re-signifying and crossing with the migration category via the migration experience. It is in this experience where the migrants’ oppressions are suffered or reconfigured with the elements found in the destination in a continual coming and going across new borders, new inequalities and minimal privileges.

Unlike the statements by Torres and Anguiano (2016) regarding Mexican migrants in Arizona about labor division by sex and the strategies of public invisibilization to manage the adaption and stay in the United States, people from Buenavista are neither invisible nor divided by sex or by undocumented status. Conversely, they retreat and restrict their interactions within the enclave to protect themselves as a collective. The Buenavista ethnic enclave comprises speakers of the same language, from the same place that make compact groups isolated from the rest of the population, they hire in similar places and recreate cultural patterns in their destinations, which enables them to recreate their ethnic identity (Güemes, 1984). Marcuse (2001) points that an enclave is the way in which minorities respond when they feel that their identities are threatened, thus strengthening their collective identities.

This way, the enclave works as a strategy that enables the migrants to contain their identities from their concentration in certain areas, permitting intra-group interaction, the reproduction of collective memory and sociocultural practices, reinforcing their group identity and establishing at the same time borders with other groups through their discourses in which categories and adjectives associated with the ethnicity of those others are underscored; in this case, African-Americans, Central Americans and Americans. As García (2006) reports for the case of Spanish migrants, the importance of belonging to migration networks is a preamble to the integration of migrants into the receiving society since networks enable labor integration and also offer support for a less traumatic adaptation.

CONCLUSIONS

According to Aguirre Beltrán (1967), refugee areas are marginal regions where natural conditions act as physical barriers, in this case the threat of Others. Their constitution as marginal areas made the inhabitants receive fewer external attacks, enabling them to preserve identity features to face acculturation processes experienced by other groups outside the refugee areas.

The Buenavista ethnic enclave works as a sort of refugee area regarding the Others, as it locates in marginal housing areas and labor sectors. However, unlike the refugee areas conceptualized by Aguirre Beltrán (1967), in the Buenavista ethnic enclave migrants from Buenavista indirectly interact with the others, African-Americans and Central Americans, establishing border for them –as natural barriers– via the discourse and the adjudication of adjectives with which they enclose those others. Group interactions that enable identity contention are also shaped and embodied in the enclave.

We have noticed the outward role of the enclave; the others are excluded from the enclave by means of establishing discursive borders and xenophobic practices that enable defining the other by means of negative categories. The enclave also has inward functions nevertheless, as it works as an element of identity support and contention for individuals from Buenavista to boast about buying clothes deemed ranch-style they brought from Buenavista, Chiapas, such as Topeka pants and checked shirts, which gives feedback to the ranchero style expressed in the norteño style of speaking and behaving. Food and religious practices are also preserved in the Buenavistita enclave, for example, we recorded two celebrations: the Day of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the Day of the Holy Death, both celebrated with much sought-after dishes: cochito horneado [roasted piglet], bola tamales and cabeza de res horneada [roasted beef head] (J. Núñez, field diary, August 6, 2017).

The ethnic enclave created by mestizo migrants from Buenavista living in Maryland, US, works as a strategy that enables them to define ethnic borders for African-Americans and Salvadorans, which facilitates their identity contention processes by establishing the referents against which they contrast their own identity. In parallel to the establishment of ethnic borders, the enclave also works as a strategy of solidarity, encounter and interchange of experiences and machines of dreams, hopes and memory generation, making the reproduction of the central core of the Buenavista mestizo identity easy.

REFERENCES

Aguirre Beltrán, G. (1967). Regiones de refugio: El desarrollo de la comunidad y el proceso dominical en Mestizoamérica. México: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. [ Links ]

Aquino Moreschi, A. (2010). Migrantes chiapanecos en Estados Unidos: los nuevos nómadas laborales. Migraciones Internacionales, 5(4), 39-68. [ Links ]

Basch, L., Glick Schiller, N. y Szanton Blanc, C. (1994). Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Berteaux, D. (2005). Los relatos de vida. Perspectiva etnosociológica. Barcelona: Ediciones Bellaterra. [ Links ]

Cruz-Salazar, T. (2015). Experimentando California. Cambio generacional entre tzseltales y choles de la selva chiapaneca. Cuicuilco, 22(62), 217-239. [ Links ]

De Genova, N. (2008). "American" Abjection: "Chicanos," Gangs, and Mexican/Migrant Transnationality in Chicago. Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies, 33(2), 141-174. [ Links ]

Department of Health and Mental Hygiene of Maryland. (2013). Hispanics in Maryland: Health Data and Resources. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene of Maryland. Recuperado de https://health.maryland.gov/mhhd/Documents/Hispanics%20in%20Maryland%20Health%20Data%20Resources.pdf [ Links ]

Faist, T. (2005). Espacio social transnacional y desarrollo: Una exploración de la relación entre la comunidad, estado y mercado. Migración y Desarrollo, (5), 2-34. [ Links ]

Gaete, R. y Rodríguez, C. (2010). Una aproximación al análisis de las cadenas migratorias en España a partir de la Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes. Revista de Ciencia Política. 30(3), 697-721. [ Links ]

Gall, O. (1999). Racismo, modernidad y legalidad en Chiapas. Dimensión Antropológica, 15 , 55-86. [ Links ]

García Canclini, N. (1993). El consumo cultural y su estudio en México: una propuesta teórica. En N. García Canclini (Coord.), El consumo cultural y su estudio en México: una propuesta teórica, (pp. 15-42). México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [ Links ]

García de León, A. (1991). Ejército de ciegos: testimonios de la guerra chiapaneca entre carrancistas y rebeldes, 1914-1920. México: Ediciones Toledo. [ Links ]

García de León, A. (1997). Resistencia y Utopía: Memorial de agravios y crónica de revueltas y profecías acaecidas en la provincia de Chiapas durante los últimos quinientos años de su historia. Colección Problemas de México. México: Ediciones ERA. [ Links ]

García de León, A. (2002). Fronteras Interiores, Chiapas: Una Modernidad Partícula. México: Editorial Océano. [ Links ]

García, J. A. (2006). Migraciones, inserción laboral e integración social. Revista de Economía Mundial, (14), 231-249. [ Links ]

Giménez, G. (2001). Cultura, territorio y migraciones. Aproximaciones teóricas. Alteridades, 11(22), (22), 5-14. [ Links ]

Giménez, G. (2009). Cultura, identidad y memoria. Materiales para una sociología de los procesos culturales en las franjas fronterizas. Frontera Norte, 21(41), 7-32. [ Links ]

Gomberg-Muñoz, R. (2011). Labor and Legality: An Ethnography of a Mexican Immigrant Network. Reino Unido: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Güemes, L. O. (1984). Enclaves étnicos en la Ciudad de México y área metropolitana. En Anales, (pp. 127-163). México: Centro de Investigación y Estudios en Antropología Social/Ediciones de la Casa Chata [ Links ]

Jáuregui, J. A. y Ávila, M. (2007). Estados Unidos, lugar de destino para los migrantes chiapanecos. Migraciones Internacionales, 4(1), 5-38. [ Links ]

Khan, H. y Wiener, A. (1967). The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years. Nueva York: Editorial Macmillan. [ Links ]

Levitt, P. y Glick-Schiller, N. (2004). Perspectivas internacionales sobre migración: conceptualizar la simultaneidad. Migración y Desarrollo, (3), 60-91. [ Links ]

Levitt, P., DeWind, J. y Vertovec, S. (2003). International Perspectives on Transnational Migration: An Introduction. The International Migration Review, 37(3), 565-575. [ Links ]

López, J., Sovilla, B. y Escobar, H. (2009). Crisis económica y flujos migratorios internacionales en Chiapas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 51(207), 37-55. [ Links ]

Luque, J. (2004). Transnacionalismo y enclave territorial étnico en la configuración de la ciudadanía de los inmigrantes peruanos en Santiago de Chile. Revista Enfoques: Ciencia Política y Administración Pública, 3, 81-102. [ Links ]

Marcuse, P. (26 de julio de 2001). Enclaves Yes, Ghettoes, No: Segregation and the State [conference paper]. In International Seminar on Segregation in the City. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. [ Links ]

Martínez, G. R. (2014). Chiapas: Cambio social, migración y curso de vida. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 76(3), 347-382. [ Links ]

Massey, D. y Aysa, M. (2007). Capital social y migración internacional en América Latina. En P. Leite, S. Zamora y L. Acevedo (Eds.), Migración internacional y desarrollo en América Latina y el Caribe, (pp. 483-518). México: Consejo Nacional de la Población. [ Links ]

Mercado-Mondragón, J. (2008). Las consecuencias culturales de la migración y cambio identitario en una comunidad tzotzil, Zinacantán, Chiapas, México. Revista de Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo, 5(1). 19-38. [ Links ]

Poggio, S. (2007). La experiencia migratoria según género: salvadoreñas y salvadoreños en el estado de Maryland. La Aljaba, 11, 11-26. [ Links ]

Portes, A. (2000). Teoría de inmigración para un nuevo siglo: problemas y oportunidades. En F. Morente (Ed.), Cuadernos étnicas: inmigrantes: claves para el futuro inmediato, (pp. 25-60). España: Universidad de Jaén [ Links ]

Portes, A., Guarnizo, L. E. y Haller, W. J. (2002). Transnational Entrepreneurs: An Alternative form Inmigrant Economic Adaptation. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 278-298. [ Links ]

Riesco-Sanz, A. (2010). Empresarialidad inmigrante: inmigración y comercio en Embajadores/Lavapiés. En A. Pérez-Agote, B. Tejerina y M. Baraño Cid (Eds.), Barrios multiculturales: relaciones interétnicas en los Barrios de San Francisco (Bilbao) y Embajadores/Lavapiés, (pp. 260-279). Madrid: Trotta. [ Links ]

Rus, J. y Rus, D. (2013). El impacto de la migración indocumentada en una comunidad tsotsil de los Altos de Chiapas 2001-2012. En Anuario 2012, (pp. 199-218). México: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica/Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. [ Links ]

Toledo, S. (2013). De peones de fincas a campesinos. Transformaciones agrarias y domésticas en el norte de Chiapas (siglos XX-XXI). Entrediversidades: Revista de ciencias sociales y humanidades, 1(1), 13-41. [ Links ]

Torres, E. y Anguiano, M. T. (2016). Viviendo en las sombras: estrategias de adaptación de familias inmigrantes mexicanas en Arizona. Papeles de Población, 22(88), 171-207. [ Links ]

Velasco, L. (1998). Identidad cultural y territorio: Una reflexión en torno a las comunidades transnacionales entre México y Estados Unidos. Región y Sociedad, 9(15), 106-130. [ Links ]

Villafuerte, D. y García, M. (2006). Crisis rural y migraciones en Chiapas. Migración y Desarrollo, (6), 102-130. [ Links ]

Zavella, P. (2011). I'm Neither Here nor There: Mexicans' Quotidian Struggles with Migration and Poverty. Durham, Carolina del Norte: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

3There is no Mexican phenotype, our italics emphasize the racialization of the population from Mexico. We claim that in Mexico there is cultural racism on the basis of persistent inequalities and which are ordered by differential categories and group people by class nd ethnicity to justify such inequalities. This turns into embodied or biological differences that in reality have cultural, economic nd social logics and origins. What takes place between mestizos and indigenous is experienced by mestizos from Buenavista when they are considered just other Latin Americans and so discriminated.

4There is a space in time between these two moments that does no record the departure of individuals from the Frailesca Region in the eighties as well, for they were only a trickle. Specifically, we found the record of a single migrant from Buenavista, Nicolás Guillermo. The Frailesca Region was favored by agricultural development plans as of the 1990’s and the population was contained in the region. Mass migration came after the rural crisis in the second half of such decade.

Received: August 20, 2020; Accepted: November 17, 2020

texto en

texto en