Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.32 México 2020 Epub Feb 10, 2021

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.1973

Article

Agreements and Conflicts in Two Chuj Border Towns Between Mexico and Guatemala

1Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social-Sureste, México, ludivina_m2@hotmail.com

This article ethnographically describes agreements and conflicts present in a border fragment shared by two Chuj communities: El Quetzal, located in Guatemalan territory, and Tziscao in Mexico. This paper intends to reflect and analyze how border communities maintain agreements and conflicts as inherent phenomena of daily social and dynamic relationships. The conformation of the border territory is contextualized from the delimitation of the geopolitical border in 1882, also differentiated accesses to material goods and services, which are possible from the national condition of its inhabitants, are presented. In this process, a series of agreements and conflicts related to domestic water, commerce, tourism activities, and the border crossing of the Guatemalan population to Mexico arise. Finally, it is observed that amid conflicts existing socio-cultural relations of continuity and stories of reciprocity sustain the social relations of the Chuj cultural group.

Keywords: agreements; conflicts; border; Mexico; Guatemala

Este artículo describe etnográficamente algunos acuerdos y conflictos que se presentan en un fragmento fronterizo compartido por dos comunidades chuj que viven en El Quetzal, ubicado en territorio guatemalteco, y en Tziscao, localizado en México. Este trabajo se propone reflexionar y analizar las formas en que las comunidades fronterizas sostienen acuerdos y conflictos como fenómenos inherentes de las relaciones sociales y las dinámicas cotidianas. Se contextualiza la conformación del territorio fronterizo a partir de la delimitación de la frontera geopolítica delimitada en 1882, y se muestran los accesos diferenciados a bienes y servicios que son posibles a partir de la condición nacional de sus habitantes. En este proceso surge una serie de acuerdos y conflictos vinculados con el agua doméstica, el comercio, las actividades turísticas y el cruce por la frontera de poblaciones guatemaltecas hacia México. Finalmente, se observa que en medio de los conflictos existen relaciones socioculturales de continuidad e historias de reciprocidad que sostienen las relaciones sociales del grupo cultural chuj.

Palabras clave: acuerdos; conflictos; frontera; México; Guatemala

INTRODUCTION

Conflicts and agreements among border communities in Mexico's southern border can be partly explained as two inherent phenomena in social relationships and everyday dynamics. However, social relationships occur in myriad forms, and conflict and dispute are among many other phenomena that reveal social life: concealment, acceptance of contradictions, and amnesia are widespread forms of social relationships experienced by communities that share a territory (Marié, 2015).

In this regard, the Mexico-Guatemala border is characterized by both conflict and agreement; therefore, both phenomena should be considered simultaneously. These historical forms of social relationships are supported by a pair of opposing tensions identified by Castillo (1994, 1999) as proximity and distance. The author states that, in the border between Mexico and Guatemala, proximity is not only geographical, but also in terms of living conditions, linguistics, and sociocultural patterns. The geographical border "separates" and creates distance, but the boundary is, in turn, traversed by the social dynamics that bond communities together.

Not every conflict is identical throughout the southern border: each part of the line between Mexico and Guatemala has its own peculiarities. However, the region presents many examples of neighboring communities living in similar scenarios, for instance, the communities of El Quetzal, in Guatemala, and Tziscao, in Mexico. Even though both border communities have established a series of agreements and arrangements, conflicting interests around everyday dynamics often lead to tension and conflict.

These complex relationships are described and explained by the historical processes that have shaped the border territory. The creation of the 1882 national border separated a number of communities, and at the same time, differentiated the inhabitants according to their nationality.

Kauffer Michel (2011) points out that the demarcation of Mexico and Guatemala's geopolitical border in the late nineteenth century gave rise to a series of conflicts and asymmetries. On the other hand, Castillo (2002) indicates that these split scenarios are also spaces of continuity, affinities, and similarities that acquire cross-border dimensions.

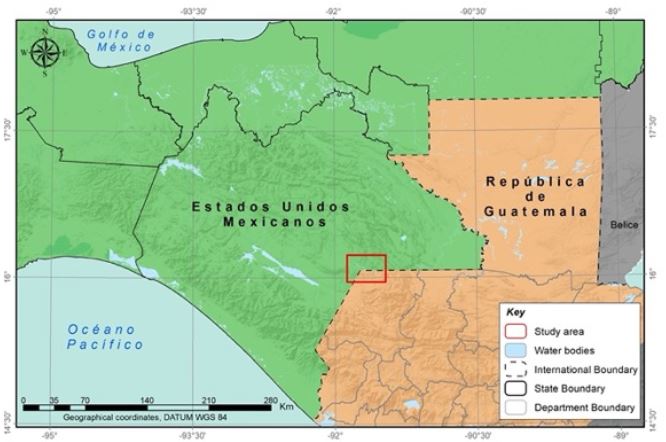

The municipalities of Tziscao, located in the southeast part of Chiapas, and El Quetzal, in the northwest part of the department of Huehuetenango, share a stretch of the border between Mexico and Guatemala near the Vértice de Santiago (See map 1). Abundant water characterizes this geographical area; it is home to the Montebello Lagoon System, composed of 59 water bodies, most of them on the Mexican side, and part of a lagoon on the Guatemalan side; this aquifer is called the Binational Lagoon, and it is divided by the geopolitical frontier.

Source: Thematic layers using data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, 2010), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food (MAGA, 2005). Created by César Octavio Sánchez Garay.

Map 1. Territorial analysis unit on the Mexico-Guatemala border

El Quetzal and Tziscao are neighboring communities separated by the border. To cross from El Quetzal to the federal highway on the Mexican side, people cross a stretch of approximately two kilometers through land that belongs to Tziscao. The remoteness of El Quetzal from commercial and economic centers on the Guatemalan side and the lack of public health services, electric power, education, communications, and transportation services have forced its population to negotiate and make agreements with the Tziscao community.

In 2008, a series of agreements were made concerning water for domestic use by families in Tziscao in exchange for health and education services that Tzicao authorities would provide to people from El Quetzal, in addition to vehicle transit permits to cross the border and access the Mexican federal highway. Furthermore, during that time, the number of tourists seeking to see the lagoon system or cross the border to visit Guatemala increased, and the number of businesses grew on both sides. Competition and control overt the touristic sector led to the fragmentation of agreements and, consequently, tension and conflict emerged.

Open conflict was the outcome of a period of concealment and simulation. In 2012, the inhabitants of Tziscao blocked the transit of vehicles from Guatemala to Mexico. On that occasion, the people from El Quetzal took advantage of their attributes and condition as Mexican nationals to prevail over their neighbors. Proximity was disrupted when both groups' interests were at stake, and the role of the border emerged to mark the distance.

In this context, our purpose is to reflect on and analyze the ways in which border communities make agreements and manage conflicts as inherent phenomena of social relationships and everyday dynamics.

The present article is divided into four sections; the first section presents an analysis of agreements and conflicts from different actors' perspectives. Subsequently, reference is made to the historical context of the geopolitical frontier configuration that split the El Quetzal and Tziscao communities between Mexico and Guatemala. The third section describes the agreements, disputes, and conflicts that arose between the two cities in 2008, focusing on four areas: water, commerce, tourism, and border-crossing; details on how family relationships decrease tensions are also given: family and business networks are bridges for interaction in everyday life and community processes. Conclusions are presented in the final section.

AGREEMENT AND CONFLICT AS PART OF SOCIAL RELATIONS

Addressing conflict as a social relationship entails differentiating it from scenarios of war or rupture; in that sense, conflict can be explained theoretically, empirically and historically (Wieviorka, 2010). Marié (2004) views conflict as a characteristic of social relationships that sometimes occur as low-intensity events that rarely turn out to be violent or expressed as an open conflict. The author explains that this can be due to the ambiguities of social life, for instance, when individuals use force or cunning, violent acts or negotiation. In other words, social actors resort to different strategies and use different mechanisms whose manifestations result in paradoxical behaviors.

Lederach (1992) highlights the importance of analyzing conflicts as processes to find the essence of the problem and never assuming that the cause is already known or ignoring the many interconnected issues. The author indicates that the epicenter is often the history of the conflict, a historical-cultural process that can favor conflictive relationships; that is, it is necessary to look at the conflict comprehensively, within a network of relationships, and never separately.

According to Wieviorka (2010), the issue of conflict in social relationships is not limited to a confrontation between enemies: it can also be a relationship between adversaries who share cultural references. Additionally, although not all conflicts are violent, they include certain aspects of violence. If violence is continuous, it settles, and if all capacity to control and limit violence is lost, it escalates the conflict and leads to other rupture logics. Even in its most critical forms, conflict is not alien to agreement and moderation, which highlights that both phenomena, agreement, and conflict, can be understood as part of the complex nature of social relationships.

Therefore, conflict can become a permanent form of social regulation and create rules and norms for a given space (Marié, 2004). As proposed by Panfichi and Colonel (2011), conflict is also a modular phenomenon, alternating critical moments with latency states, and taking different forms. In any case, it can be described as a relational dispute whose permanent axis is social friction (Mejía, 2013).

An important highlight in this regard is Hoffmann's (2009) proposal to take into account the economic, social, and cultural heterogeneity of societies in conflict. This view reveals complex processes often understood in terms of antagonisms between groups, although they are often revealed as complex combinations of interests and positions.

It also helps avoid perpetuating the conflict by linking it to a single fact, but instead to the modalities of negotiation and multifaceted adaptation between different logics and recompositions that interact at different levels (Hoffmann, 2009). This is how negotiations arise from historical alliances or from reciprocal relationships established when territories are shared.

This is the case in the Mexico-Guatemala border, shaped by geopolitical delimitation in the area of conflict and the social continuity resulting from the dynamics of regional forces described by Castillo (1999), which prevailed over the interests and capabilities of the central powers. In this way, exchanges and links between neighboring peoples have laid the foundations of a border region. This, of course, is not to say that the hegemonic relationships between the Mexican and Guatemalan states are not reproduced in these local cross-border scenarios. The following section describes the conformation of the border in this context.

Configuration of the geopolitical border between Mexico and Guatemala

The border territory shared by Mexico and Guatemala was shaped by conflict, power relations, and colonizing policies implemented by the Mexican national state (Cruz, 1998; De Vos, 1993 and 2005; Hernández, 2001; Limón, 2007, 2008).

The border was also under the influence of power groups operating at the regional, national, and international levels. De Vos (1993) points out that these groups ended up focusing, deciding, and acting far beyond the scope that they had initially established, and the people caught within the border region saw the new boundary as an expansion project devised and executed by to the detriment of many.

This border is legally explained by the configuration of the Mexican national state, and it is strengthened by the colonization of spaces considered to be "empty". Therefore, state power was at the same time individualizing and totalizing, as demonstrated by the implementation of the centralizing and homogenizing national project that the Mexican state reinforced during the twentieth century.

Mexico's political strategies to strengthen the border and colonize it permeated relations between neighboring communities in both countries. Inequalities began to emerge between people across the border. The Mexican state organized the territory, the land, the water, and the social relationships on the Mexican side, but this action brought negative consequences for the Guatemalan neighbors.

Guatemala lost a large territorial extension with the 1882 border treaty: 14 towns, 19 villages, and 54 ranches totaling more than 15 000 inhabitants became part of Mexican territory, whereas only one village and 28 ranches, home to 2 500 inhabitants, became part of Guatemala. Additionally, a large portion of the Lacandon Jungle became part of Mexico. The Guatemalan government resented losing this area, which is almost unpopulated but rich in precious woods (De Vos, 1988, 1993).

For an extended period, Mexico and Guatemala engaged in a series of conflicts over different territories. The border treaty was disadvantageous for Guatemala because it lost more territory than it gained, and conflict arose among the logging companies that had concessions in the region (De Vos, 1988)). It was not until 1895 that the national border conformation process came to an end, and the international dividing line has remained unchanged since that year. However, the construction of this border artifice affected the lives of the people in the region. De Vos (1993) mentions that peasant communities, most of them indigenous, were affected because they became peripheral areas even though they had been considered part of central regions from time immemorial.

The states were geographically and administratively separated by the border treaty, and with them, many peoples and communities. Despite their proximity, the political frontier differentiated these people from one country to the next.

Although both countries were undergoing a period of liberal reform at the end of the nineteenth century, Fábregas Puig (1992) explains that, in Guatemala, this reform resulted in various changes, especially concerning land tenure, which dispossessed ethnic groups and forced them to cross the border in 1886.

When the border was established, in 1883, the Mexican government, under the Porfirio Díaz administration, decreed the National Land Settlement Act, which allowed for the nationalization of indigenous groups, among which were the Chuj, from Guatemala, located on the banks of the Montebello Lagoon System (Cruz, 1998). This border left the village of Tziscao on the Mexican side and separated it from the neighboring village of El Quetzal, which ended up in Guatemalan territory.

Tziscao and El Quetzal: faraway so close

Studies by Cruz (1998) and Lemon (2007 and 2008) show that the inhabitants of Tziscao settled in the region after the Liberal Reformation in Guatemala in the 1870s. Lemon (2007) describes a diaspora among the San Mateo Ixtatán Chuj and the foundation of several villages, such as Subajasum, Bulej, and Tziscao, which located on the northeast slope of San Mateo, near what would later become the border. People from San Mateo Ixtatán sought new settlements because the land was still free; families began to acquire places where their crops were more productive, and more villages were built.

For his part, Cruz (1998) states that the first settlers in the area came in search of a new place to live due to conflicts in their original lands. The Guatemalan Liberal Reform and the arrival of Rufino Barrios to power in 1873 resulted in a decree stating that property titles could not be issued, and the land was transferred to large landowners to grow coffee. Simultaneously, a regulation on day laborers (1877) and an anti-vagrancy law (1878) were passed to secure indigenous labor. These circumstances led to the foundation of new centers of Ladino population in Chuj territories and the subsequent migration of native peoples to what would become Mexico a few years later. Piedrasanta (2009) affirms that ladinos played an essential role in the creation of Guatemala's national government, and their participation led to a new spatial configuration at the regional and national levels. Ladinos secured the most important political-administrative positions, especially in the peripheries, where the border would later be colonized.

In the northwestern part of Guatemala, the colonization process was accompanied by an agrarian counter-reformation policy during the 1960s and 1970s. Depopulated areas and idle lands owned by the nation were declared areas of agricultural development. However, private property was not expropriated. The Guatemalan state's goal of colonization led to the displacement of large groups of indigenous agricultural workers to faraway places lacking communications or any other type of public service. The Guatemalan government needed to create a human barrier to safeguard the border (Piedrasanta, 2009).

In the oral traditions of local elders, Tziscao was founded in 1870 by a group of Chuj families from different villages near San Mateo Ixtatán, in the Republic of Guatemala, and families living near the municipality of La Trinitaria, in Mexico. However, with the 1882 Mexican-Guatemalan border treaty, Tziscao was one of the settlements that became part of Mexican territory.

Source: Thematic layers using data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, 2010), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food (MAGA, 2005). Developed by: César Octavio Sánchez Garay.

Map 2. Geographical context of the study

The region became legally integrated to Mexican territory after the signing of the border treaty between Mexico and Guatemala in 1882. One year later, a law regulating the colonization of national lands was enacted in Mexico, including the Chuj indigenous people who lived in the community of Tziscao (Mejía & Peña, 2015).

As a result of the colonization process, ten families from Tziscao obtained ownership documents of the lands where they had settled. They began to grow corn, beans, and squash. Their proximity to the lagoon allowed them to carry out fishing activities to complement their diet. Their sense of belonging grew with the population as new commercial and administrative relationships began to form, allowing them to establish relationships with the municipal capitals of Comitán and La Trinitaria, in Chiapas, Mexico. At the same time, members of this colony were still temporary workers in coffee plantations near the Chiapas jungle in Mexican territory, where they moved during harvesting seasons.

The ten families who settled Tziscao lagoon's shores were endowed with land ownership titles and the communal lands called El Ocotal. Using these documents, the inhabitants obtained the right to use and exploit the lands, mountains, lagoons, and all the natural resources available for them to live.

However, Tziscao (located within the Montebello Lagoon System) was included in a polygon of almost 6 500 hectares named Lagunas de Montebello National Park, which was formally subjected to political and administrative control by the then Secretariat of Agriculture and Livestock.

For the inhabitants of Tziscao, land was the main asset and sustenance of family life. However, their daily dynamics were governed by the changes taking place at the national level, such as the Mexican federal government's policies associated with settlement forms, land distribution, and change in territorial boundaries.

The fact that Chuj indigenous groups obtained commonly used lands and a Mexican national identity created marked differences. While the inhabitants of Tziscao were given the right to own communal lands, and later ejido lands, those who remained on the other side of the border were still peones in the coffee plantations located in the lands where they lived; these families continued as day laborers in the Maber farm, which is now officially recognized as El Quetzal farm in the Guatemalan census.

Chuj families remaining on the Guatemalan side also suffered greatly due to the internal armed conflict experienced by Guatemala during the 1980s, and sought refuge on the Mexican side. Most of these families settled in camps and in family homes near the border. Their geographical proximity to Mexico saved the lives of many families and communities, keeping them from persecution and aggression in their own villages. The kind welcoming of Guatemalan refugees by Mexican communities was due to the historical relationships of these neighboring peoples who shared ethnic origins and sociocultural affinities (Castillo, 1994).

Many families returned to Guatemala after the 1990s; despite their social fragmentation and the period of great violence they experienced, they began rebuilding their villages. Over time, people from El Quetzal fought and paid to own their lands.

At present, the inhabitants of these towns are far from the capital and have to use dirt roads and public transportation for approximately 18 hours to get to Guatemala City. For instance, Nentón, the municipal capital of the department of Huehuetenango, is two hours away from El Quetzal, and public transportation is not constant. This remoteness from the administrative, commercial, and economic centers and the lack of local public health and electric power services, have led the population of the village to negotiate and make agreements with the Tziscao population concerning their passage across the border and other services. Families in El Quetzal need to cross the border to reach the community of Tziscao, on the Mexican side, to access the federal highway that takes them to the municipal capitals of Comitán and La Trinitaria.

The international border separates the towns of El Quetzal and Tziscao. However, both share a Chuj identity and a water-rich territory, which has become a touristic place of great importance over the past years.

The international division of the lagoon located between Tziscao and El Quetzal is demarcated by the line of buoys. Photograph taken by the author.

Photograph 1. Mexico-Guatemala International Lagoon

Living on the banks of the Tziscao lagoon and the international lagoon has allowed the inhabitants of both communities to carry out various activities such as fishing or conducting recreational activities for tourists. Water is used for domestic purposes, and in the past, it was used for human consumption; the fact that the area is humid and fertile allows inhabitants to grow corn, bean, and coffee.

Tourism and commerce are permanent activities. Women's daily lives, as well as men's, boys', and girls' revolves around these sectors; therefore, they engage in diverse activities such as selling food or handicrafts in touristic paradors or acting as tour guides, rafters, or boathouse managers. Others work collecting tolls or are responsible for local transportation. In addition to displaying the natural beauty of the lagoon system, the border is part of the landscape.

Neighboring communities: between agreements and conflicts

Living on the border involves negotiating passage. Although both communities have free transit to cross the border due to the lack of a migratory control post, the inhabitants of El Quetzal are usually in disadvantage because they have to cross through lands owned by the community of Tziscao to reach the road that connects with the rest of the Mexican territory. This two-kilometer stretch consists of a dirt road that becomes one of the main streets in Tziscao.

Tziscao authorities considered that they had to share responsibilities with the people of El Quetzal to maintain the road, which was used not only by the locals but also by tourists. Thus, an agreement was established in 2008 in which villagers from El Quetzal committed to maintaining the dirt road. In addition, some families in Tziscao would be given water for domestic use, which they would obtain from the El Quetzal springs, located in Guatemalan territory. The agreement also granted families from El Quetzal the use of Tziscao's health and education services, although some were already using some of these services.

Although the largest lagoon belongs to Tziscao, the population has always faced the problem of lacking piped water in their homes and has had to use the lagoons, springs, and streams near the community; water is hauled in pitchers.

Source: Tziscao, Chiapas, Mexico. Photograph taken by the author.

Photograph 2. Women hauling water for domestic use in Tziscao

Tziscao's authorities built a water storage tank on lands that were part of El Quetzal, and another tank was built on the Mexican side. Water was distributed from this location to the Parador Internacional and some houses in the lower part of the village; the supply was not enough for these purposes, and many families continued carrying water.

The agreements made by the authorities in both towns were broken at the end of 2010 when inhabitants of El Quetzal cut the hose and prevented the water from reaching the storage tanks. This event set off a series of tensions among the population of Tziscao. Villagers point out that they had to level up with Tziscao's authorities because they were charging their passage even though they had repaired the road the previous year. El Quetzal refused to pay the amount of 8,000 pesos demanded by Tziscao's authorities, and in response to their annoyance, they decided to block the hoses carrying water to their homes.

Both sides had their own positions and stood up their rights. Despite these actions, Tziscao's inhabitants could not close the border because they were also benefited by the tourism crossing into Guatemala. Additionally, Guatemalan tourists crossing the border to visit the lagoons on the Mexican side have increased in recent years.

In 2010, the border became more dynamic as a result of increased tourism. However, visitors prefer to buy handicrafts when they cross to Guatemala instead of buying them on the Mexican side, where the same types of souvenirs are sold. This business has been another source of tension between both communities. Currently, women's businesses in Tziscao, who have been selling handicrafts from the neighboring country for years, have decreased due to the competition of businesses owned by families in El Quetzal, across the border.

Crossing the border has been a contentious issue, which has worsened in recent years. On March 1, 2012, Tziscao's authorities announced that access to El Quetzal would be restricted; they placed a sign on the way to the village, stating that crossing the border would be allowed only within a fixed schedule. They also placed a chain to close the road physically.

Source: Tziscao, Chiapas, Mexico. Photograph taken by the author.

Photograph 3. Border crossing regulations

The ejido assembly in Tziscao claimed the right to charge vehicles belonging to people from El Quetzal and everyone who traveled from Guatemala to Mexico. It was also a way to compensate for the lack of compliance by the villagers on the other side, who had failed to maintain the road and provide water to Tziscao.

Payment rates differed. For vehicles coming from El Quetzal and headed to the federal highway on the Mexican side, the cost was 30 pesos, and for those from other Guatemalan locations, it depended on the type of vehicle and its cargo, and it could be as high as 150 pesos in some cases. This form of payment was much resented, and Guatemalans would refer to it as an act of injustice by their Mexican neighbors because people from El Quetzal had no other choice.

Tziscao considered that the best decision was to allow free access for a few months to de- escalate the conflict, even though they knew that the border was a dangerous space, where groups of migrants and vehicles carrying cargoes that they were unaware of could use for crossing. People who lived near the road observed how Tziscao had become a busy place over the past 10 years due to the opening and rehabilitation of the dirt road that connects El Quetzal with other villages, towns, and municipalities in Guatemala. However, this traffic was more frequent during the afternoon and at night, which was why the border was open only in the morning.

The regulatory measures adopted by the ejido assembly concerning the border crossing were permeated by a series of situations that they faced as neighboring communities beyond the broken agreements in this regard and those related to water. Tourism and commerce had also become sources of tension. Both communities wanted to increase their number of visitors to increase their income. However, Tziscao has a more vital tourism-focused infrastructure, and much of the daily tasks carried out by men and women are associated with this activity, for example, taking tourists in boats around the lagoons, conducting tours, providing food and accommodations services, and working at the cabins managed by the ejidatarios. In addition, many families manufacture and sell handicrafts.

There is a marked difference in terms of income: people from Tziscao provide all the services listed in previous paragraphs, whereas inhabitants from El Quetzal only sell handicrafts and other products based on cardamom, coffee, and cocoa. Despite these differences, El Quetzal has the advantage of being on the Guatemalan side, where many tourists cross and buy their products.

Touristic activity gave families from El Quetzal the strength to make decisions, although it brought further consequences. For example, in October 2012, the El Quetzal authorities managed to buy the land where the dirt road that leads to Tziscao is located, on the Mexican side.

Tziscao's ejido leaders did not approve this real estate operation: the agreement was made directly between the owner of the land and El Quetzal's authorities. The owners of El Quetzal decided to rehabilitate and pave an approximately 400-meter section. When the construction work was finished, Tziscao's authorities prevented vehicles from crossing the border by obstructing the beginning and end of the road with large ditches, and later, with the construction of a concrete wall whose intention was to disguise the conflict into the landscape.

Source: Tziscao, Chiapas, Mexico. Photograph taken by the author.

Photograph 3. Border crossing regulations

These barries marked a line between the neighbors across the border, and the geopolitical boundary was reinforced when El Quetzal villagers resorted to Guatemalan consulate authorities to intervene in the conflict. However, the authorities failed to address this issue. The International Boundary and Water Commission considered this conflict as a local matter for the local populations to solve. Tziscao validated the national border, arguing El Quetzal was forbidden to carry out any construction work and ratified the natural conservation area as a shield, arguing that Tziscao was inside a National Park, where paved roads are not allowed.

The construction of this wall strengthened the division between Mexicans and their Guatemalan Chuj neighbors. Currently, both countries' flags are displayed along the border to express the binational identity of the region. The obstruction of this road affected the villagers in their daily lives; for example, the inhabitants of El Quetzal cannot use vehicles to transport products bought in Mexico and need to carry them on their back, and it has become very difficult to take patients to clinics on the Mexican side.

Conflicting relationships are ever-present as a part of everyday life, and they manifest themselves as tension or frictions. Very often, these issues are concealed to tourism. but cross-border family and business relationships and religious activities continue. In this context, it can be observed that the limit is not in each person who traverses it because it is not an individual matter, and the national border is collectivized.

Family and business relationship networks

Conflicts between El Quetzal and Tziscao are mainly mitigated by sociocultural, kinship, and labor relationships. For example, there are relationships between parents and children, among siblings, compadrazgos and friendships, even marriages that develop on both sides of the border. Family reunions, including members of both communities, family visits across the border, and shared celebrations such as birthday parties and weddings are the norm. Families and young people from El Quetzal attend the ceremony and dance in honor of the Virgen de la Candelaria, held on February 2 in Tziscao.

Family relationships are not bound by specific rules or norms, but there are certain considerations concerning marriages, especially among Tziscao families. Parents often prefer that their daughters marry men from the same community because they are considered more capable of providing economic resources into the family, and sons inherit ejido-related rights, including lands and permission to profit from tourism.

Mexican men from Tziscao can marry women from outside the community, Mexican or Guatemalan, and take them to live there. However, Mexican women from Tziscao who marry men from other places, Mexican or Guatemalan, must leave their family and community because the husband could not live in the ejido, much less obtain land tenure rights or live off tourism. Current marriage practices in Tziscao show how rights are conditioned by rules and regulations established with a focus on ownership and tourism.

Another strong relationship between Tziscao and El Quetzal is in the services sector. Employees are mainly women from El Quetzal hired by restaurants, touristic paradors, and cabins owned by Tziscao families. They perform tasks such as making tortillas, washing clothes, cleaning cabins, or helping in the kitchen. Guatemalan women employed in these jobs walk more than 500 meters to the Mexican side every day. At the end of their day's work, they return to their village to carry out their family tasks; contracts for these activities are not permanent. They depend on the seasonality of tourism, although in recent years, many women from El Quetzal have been employed in their hometowns to support the handicraft business and to diversify the activities available to tourists.

Tziscao's local tour guides have made certain agreements with handicraft business owners from El Quetzal. One of them involves commissions paid to tour guides by owners of handicraft shops for bringing in tourists; these commissions depend on the number of visitors brought in and how much they shop.

Another major aspect of the relationship between these communities has to do with communications, especially concerning cellphone coverage. Tziscao is provided this service by Tigo2 , a Guatemalan company whose coverage includes part of the Mexican side. Both communities, along with many others near the border, use the same local telephone code. People from Tziscao resorts to small establishments in the neighboring village to buy cellphone access, although Tigo has opened two small stores to sell the service in Tziscao. Tziscao lacks cellphone coverage provided by a Mexican company; therefore, calling any part of the Mexican territory from this population involves an international call.

The sociocultural, family, economic, and mobility relationships between these two communities reveal their being part of a single Chuj group that has existed since before the creation of the national border. Their family, friendship, and compadrazgo bonds act as connections that support regional proximity.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding conflicts and agreements as part of social relationships and historical processes, as proposed by Marié (2004), Wieviorka (2010) and Lederach (1992), refers to various discussions and ways of looking at border issues; the point is not to minimize such events, nor to overlook the fact that unequal relationships arise amidst conflicts related to nationality and other economic, political, or cultural components of each situation, as the present case study has shown. To gain leverage, each community makes strategic use of its resources, for example, access to water, the border, national condition, tourism, and commerce.

The present study showed that the conflict often takes different forms, and its violence level is not always the same. Conflict is concealed from tourism to present an image of peace that matches the characteristics of the landscape in the Montebello Lagoon System. But everyday social friction and the need to tolerate contradictions are always there.

The border takes different nuances depending on the context. Distance and proximity (Castillo, 1999) make the border somewhat flexible, mobile, and accessible. It provides different types of access to material goods and services based on the national condition of inhabitants and settlements. These differences have resulted in two separate groups, one of them having ample rights while the other is excluded. The border is also between Mexican and Guatemalan national sovereignty, which is visible in historical decisions and interests where countries are politically divided. This explains the structural tensions at the national level and the lack of binational cooperation.

Both frontiers are the result of decisions made by hegemonic groups, which is reproduced at the local scale. Dehouve (2001) states that the administrative policies established by the national state are governed by a principle of inequality among territorial units, which can determine local conflicts and dynamics related to competition.

The case of Tziscao and El Quetzal is an example of how the Mexican and Guatemalan governments have introduced a differentiation reflected in the decisions made by these communities to negotiate border crossings or to agree on the health- water- or communications-related services that governments themselves cannot provide in peripheral locations such as the study area. Other sectors, such as tourism and commerce, where neighboring places compete for higher income. However, agreements, arrangements, and sociocultural relationships of continuity, as well as a shared and reciprocal history, remain the bridges that maintain social relationships in this border region.

REFERENCES

Castillo, M.A. (1994). Chiapas: Escenario de conflicto y refugio. DemoS, (7), 25-26. [ Links ]

Castillo, M.A. (1999). La vecindad México-Guatemala: Una tensión entre proximidad y distancia. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 14 (1), 193-218. https://doi.org/10.24201/edu.v14i1.1041 [ Links ]

Castillo, M.A. (2002). Introducción. Migraciones y movilidad espacial en la frontera sur. En E. Kauffer Michel (Ed.), Identidades, migraciones y género en la frontera Sur de México (pp. 187-192). San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. [ Links ]

Cruz, J.L. (1998). Identidades en Fronteras, Fronteras de Identidades. Elogio de la intensidad de los tiempos en los pueblos de la Frontera Sur. México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

De Vos, J. (1988). Oro Verde. La conquista de la Selva Lacandona por los madereros tabasqueños, 1822-1949. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

De Vos, J. (1993). Las fronteras de la frontera sur. México: Universidad Autónoma de Tabasco/Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores de Antropología Social. [ Links ]

De Vos, J. (2005). La formación de la frontera entre México y Centroamérica. México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. [ Links ]

Dehouve, D. (2001). Ensayo de geopolítica indígena. Los municipios tlapanecos. México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa/Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social/Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos. [ Links ]

Fábregas, Puig, A. (1992). Pueblos y culturas de Chiapas. México: Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Hernández, Castillo, R.A. (2001). La otra frontera. Identidades múltiples en Chiapas poscolonial. México: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [ Links ]

Hoffmann, O. (2009). Lugares de fronteras. Lecturas de un conflicto territorial en el sur de Veracruz, siglos XVIII y XIX. En E. Velázquez y E. Léonard, O. Hoffmann y M. F. Prévôt-Schapira (Coords). El istmo mexicano: Una región inasequible. Estado, poderes locales y dinámicas espaciales (Siglos XVI-XXI), (pp. 165-213). México: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social/Institut de Recherche Pour le Développement. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2010). Censo de población y vivienda 2010. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx [ Links ]

Kauffer, E.F. (2011). Hidropolíticas en la frontera entre México, Guatemala y Belice: La necesaria redefinición de un concepto para analizar la complejidad de las relaciones en torno al agua en escenarios transfronterizos. Aqua-lac, 3(1), 157-166. [ Links ]

Lederach, J.P. (1992). Enredos, Pleitos y Problemas. Una guía práctica para ayudar a resolver conflictos. Guatemala: Ediciones Semilla. [ Links ]

Limón, F. (2007). Memoria y Esperanza en el pueblo Maya Chuj. Conocimiento cultural y diálogos en las fronteras. Puebla: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla/Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades Alfonzo Vélez Plieg. [ Links ]

Limón, F. (2008). La ciudadanía del pueblo Chuj en México. Una dialéctica negativa de identidades. Alteridades, 18(35), 85-98. [ Links ]

Marié, M. (2004). Las huellas hidráulicas en el territorio. La experiencia francesa. San Luis Potosí, México: El Colegio de San Luis/Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua/ Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. [ Links ]

Marié, M. (2015). Presentación: La construcción de los territorios en México. ¿Qué es un territorio hoy? En G. Santacruz y F. Peña (Coords.), Miradas sobre dinámicas territoriales en México, (pp. 9-20). México: El Colegio de San Luis. [ Links ]

Mejía, L. (2013). Reapropiación del territorio lacustre de Montebello: El caso de un pueblo fronterizo chuj en Chiapas. (Tesis doctoral), San Luis Potosí, México, El Colegio de San Luis, México. [ Links ]

Mejía, L., y Peña, F. (2015). Territorios disputados: Culturas y aprovechamiento de los Lagos de Montebello. En G. Santacruz y F. Peña (Coords.), Miradas sobre dinámicas territoriales en México, (pp. 839-59). México: El Colegio de San Luis. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería y Alimentación (MAGA). (2005). Atlas temático de la república de Guatemala (Serie de recursos naturales, sociales, productivos, amenazas y vulnerabilidad. Guatemala: Laboratorio SIG-MAGA. [ Links ]

Panfichi, A, & Coronel, O. (2011). Los Conflictos Hídricos en el Perú 2006-2010: Una lectura panorámica. En R. Boelens, L. Cremers y M. Zwarteveen (Eds.), Justicia Hídrica, acumulación, conflicto y acción social, (pp. 293-422). Perú: Justicia Hídrica/Instituto de Estudios Peruanos/Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [ Links ]

Piedrasanta, R. (2009). Los Chuj, unidad y ruptura en su espacio. Guatemala: ARMAR. [ Links ]

Wieviorka. M. (2010). El conflicto social. Sociopedia.isa , (s/n), 1-10. Recuperado en http://www.sagepub.net/isa/resources/pdf/Social%20Conflict%20-%20Spanish.pdf [ Links ]

Received: March 03, 2019; Accepted: September 23, 2019

text in

text in