Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Frontera norte

versão On-line ISSN 2594-0260versão impressa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.32 México 2020 Epub 10-Fev-2021

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.1972

Article

Beyond the Border. Mobility and Family Reconfigurations Between the Chuj of Mexico and Guatemala

1Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, México, mtrguez@ciesas.edu.mx

2Instituto de Estudios Interétnicos, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala, alcaballeros@yahoo.com

In 1981, thousands of indigenous Guatemalans fled the civil war in their country, taking refuge in the first instance in Chiapas, Mexico, near the border line. In 1996 the Peace Agreements were reached, and part of the refugee population returned to Guatemala, while another fraction remained in Mexico, in localities of the states of Chiapas, Campeche, and Quintana Roo. This triple process –refuge, return, and/or definitive settlement in Mexico– resulted in new dynamics of movement and cross-border mobility, as well as in the reconfiguration of family and parental groups based on differentiated citizenship status. In this article, we provide analytical elements associated with these dynamics, based on the ethnographic observation carried out in the returnee village of Yalambojoch, in the department of Huehuetenango, municipality of Nentón, Guatemala, and in Santa Rosa el Oriente, a town in Chiapas that received refugees.

Keywords: Chuj; southern border; refuge; Mexico; Guatemala

En 1981 miles de indígenas guatemaltecos huyeron de la guerra civil en su país, refugiándose en primera instancia en el estado de Chiapas, al sur de México, cerca de la línea fronteriza. En 1996 se alcanzaron los Acuerdos de Paz y parte de esta población refugiada retornó a Guatemala, mientras que otra fracción permaneció en México, en localidades de los estados de Chiapas, Campeche y Quintana Roo. Este triple proceso –refugio, retorno y/o asentamiento definitivo en México– derivó en nuevas dinámicas de circulación y movilidad transfronteriza, así como en la reconfiguración de grupos familiares y parentales en función de estatus como ciudadanos diferenciados. En este artículo aportamos elementos analíticos vinculados a dichas dinámicas, apoyándonos en la observación etnográfica realizada en la aldea de retornados Yalambojoch, del departamento de Huehuetenango, en el municipio de Nentón, Guatemala, y en Santa Rosa El Oriente, localidad chiapaneca que recibió refugiados.

Palabras clave: chuj; frontera sur; refugio; México; Guatemala

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this article is to analyze current cross-border movement processes between Mexico and Guatemala based on fieldwork carried out in Chuj villages located in the municipalities of Nentón, Guatemala, and La Trinitaria, Mexico. The Chuj are native people of the Q'anjob'al Mayan family. Although they originated in the municipalities of San Mateo Ixtatán and San Sebastián Coatán, in Guatemala, they also settled in the municipalities of Nentón and the Mexican municipalities of Independencia and La Trinitaria.

In 1982, thousands of Guatemalan refugees, mostly Q'anjob’al, Chuj, and Mam, settled in camps in municipalities across the border, in the state of Chiapas, fleeing the armed conflict in their country. Their repatriation and return to Guatemala began in the early 1990s. Part of the refugees remained in Mexican territory, while others decided to return to their country of origin. These processes resulted in separations between parental and family groups, as well as in the diversification of the citizen status of many people.

The present study shows that Chuj families have developed mobility strategies despite the border between the two countries. However, the border is still an obstacle to the equitable and balanced development of people living in the region. For example, the migration strategy favors those who possess documents that state their Mexican or dual citizenship, as they can travel freely through Mexico until they reach the border with the United States and try to cross it. On the other hand, people who were born in Guatemalan territory and lack dual citizenship face more obstacles when they migrate to the United States or reside anywhere in the Mexican Republic. This phenomenon is analyzed in the present article. Our main goal was to record family, ethnic, and community ties between two populations located on opposite sides of the border. Our purpose was to outline and analyze different types of family configurations and organizational strategies associated with the dynamics of cross-border mobility and differentiated citizen status.

The data and reflections presented in this article are part of a study carried out within the framework of the project “The Mexico-Guatemala border: Its regional dimension and bases for its integral development.”3 This project was carried out from January 2018 to July 2019. In this article we present part of the results obtained by one of the working groups making up the research group.

METHODOLOGICAL NOTE

Fieldwork was jointly conducted by María Teresa Rodríguez, a researcher at CIESAS, and Álvaro Caballeros, a researcher at the Institute of Inter-ethnic Studies (IDEI) at USAC. The contact that made this collaboration possible occurred within the framework of the International LMI-Meso Joint Laboratory.4 The primary location for the fieldwork was Yalambojoch, a border Chuj village in the municipality of Nentón, Huehuetenango, 444 kilometers northwest from the capital of Guatemala. Yalambojoch is a village of approximately 1,400 Chuj-speaking inhabitants. Part of its population was sheltered in camps in the municipalities of La Trinitaria and Independencia (Chiapas) during the armed conflict in Guatemala from 1960 to 1996.

The strategy to access Yalambojoch consisted of the delivery of an eight-module training process called “Migration, territories, and identities in border contexts” to around 30 young Chuj men and women. Course attendees participated in focus groups and administered a survey in the village. We were also supported by families in the community to locate the villages in Chiapas where former Chuj refugees lived, and with whom they still had cultural, social, and family ties. One of them was Santa Rosa el Oriente, located in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas. Relatives of those who returned to Yalambojoch once the Peace Accords in Guatemala were signed in 1996 still lived in this village and elsewhere in Chiapas.

We visited Santa Rosa el Oriente three times in order to record some of the dynamics of cross-border Chuj families identifying the kinship networks, whose registration started in Yalambojoch. The research team consisted of an anthropologist and a sociologist, and it involved a combination of research techniques and strategies, including qualitative (genealogical diagrams, ethnographic observation, in-depth interviews) and quantitative approaches (survey, structured interviews, focus groups). The distances between the location of the studied sites and the authors’ places of residence (Xalapa, Mexico, and Guatemala City) required considerable travel time; therefore, the team stayed five times in Yalambojoch, Guatemala, and three in Santa Rosa El Oriente, Mexico, from January 2018 to March 2019.

THE CHUJ IN THE BORDER CONTEXT

Chuj people belong to the Q'anjob'al Maya family. Their language stems from proto-Mayan, a primitive language that is estimated to have been in use approximately 5,000 years ago; it is linguistically and grammatically similar to the Q'anjob'al, Jacalteco, Acatec, Tojolabal, and Mocho' languages (Piedrasanta, 2009).

In Mexico, the Chuj people inhabit the municipalities of La Trinitaria and Independencia, on Chiapas’s south border; they refer that their mythical and cultural origins are in San Mateo Ixtatán and San Sebastián Coatán, two municipalities located in the Cuchumatanes mountains, in northwestern Guatemala. Other Chuj communities are located in the border municipality of Nentón (Huehuetenango, Guatemala), and they maintain close ties with the inhabitants of La Trinitaria and Independencia.

The history of these Chuj settlements on both sides of the Mexico-Guatemala border dates from much before forced migration. There are two interpretations regarding the location of these villages in the current border region. One of them states that the liberal reforms implemented in Guatemala in the late 19th century imposed territorial spoils on indigenous peoples, among them the Chuj, which resulted in the first migrations to what is now Mexican territory, near Lagos de Montebello (Cruz Burguete, 1998; Limón Aguirre, 2009; Ruiz Lagier, 2006). The other interpretation assumes that the territory was occupied by Chuj people since before the colonial era; archaeological evidence reveals the presence of human settlements during the early Classic and Postclassic periods, as well as the establishment of housing during the early Preclassic, from 1500 B.C. to 300 A.D. (Piedrasanta, 2009; Navarrete, 1979; Ulrich & Castillo, 2015). Both interpretations are complementary, and they explain cross-border continuities and circulation flows across different historical moments.

For the Chuj, the colonial era represented the permanent presence of catholic priests and various Spanish Crown representatives, strict control of most colonial economic institutions, and forced labor. Among others, these reasons prompted the departure of numerous indigenous families from settlements established by colonial authorities. In this regard, Piedrasanta (2009) points out that waves of inhabitants from San Mateo Ixtatán Chuj fled to old agricultural sites, founded villages, and gradually repopulated their old domains (Piedrasanta, 2009).

The Guatemalan Liberal reform, which began a decade before the demarcation of the current international boundaries in 1882, led to policies that radically impacted the space occupied by Chuj populations in the country, especially through the creation of two new municipalities, Nentón and Barillas, in which the Chuj dwelled. Additionally, as part of the expansion of agricultural production, the agrarian policy imposed the dispossession of indigenous lands and favored ladinos and German immigrants (Piedrasanta, 2014; Piedrasanta, 2009). Such expropriation, enacted in 1873, led to the emigration of part of the Chuj population to areas that are now part of the Mexican territory (Cruz Burguete, 1998).

In Mexico, during the late 19th century President Porfirio Díaz promoted the settlement on the southern border by decreeing the Law for the Colonization of National Lands. Given these circumstances, the border region received indigenous peoples from the Altos de Chiapas, as well as from Guatemalan Chuj and Q'anjob'al villages from the Cuchumatanes mountains. The municipalities of Las Margaritas, La Trinitaria, and Frontera Comalapa were founded in Chiapas. The Mexican law allowed for the nationalization of indigenous people who had already migrated to Mexico from Guatemala, such as many Chuj, whose settlements surround the lake system today known as Lagunas de Montebello National Park, located in the border area of Chiapas, near Santiago el Vértice.

The demarcation between Mexico and Guatemala would radically affect the lives of the people living in towns and communities that were politically separated. These were mainly indigenous agricultural communities that had been part of central regions since time immemorial, and that quite abruptly became peripheral border spaces (De Vos, 2002). Different peoples were affected by the decisions made by the governmental spheres as the two countries defined the border, for instance, the Chuj.

The village of Tziscao (La Trinitaria, Chiapas), located in the Lagos de Montebello area, was settled in the late 1870s by a group of Chuj families from Guatemala who settled in the area (Cruz Burguete, 1998), attracted by the possibility of sowing their plots and improving their living conditions (Hernández, Nava, Flores & Escalona, 1993). Twelve years after that, the border demarcation separated the Chuj settlement, which resulted in the configuration of two different settlements: Tziscao, located in Mexican territory, and El Quetzal, in Guatemalan soil (Mejía, 2013). Concurrently, the Guatemalan liberal administration also founded new municipalities such as Nentón, in 1886, and Santa Cruz Barillas, in 1888. The growth of villages in Mexico, such as Tziscao,5 and the creation of new villages in Guatemala, such as Yalambojoch (Nentón) in 1890, were the result of analogous processes driven by liberal policies in both countries.

During the 20th century, Mexico and Guatemala experienced both parallel and diverging processes in terms of modernization and development policies. The Mexican political project, based on the 1910 Mexican Revolution, was a nationalist movement that sought to expand the welfare state and redistribute land; it showed different nuances and little success in the Mexican southeast, where profound social and economic inequalities persist.

During the Chiapas border colonization, strategic and forcible integration policies consisting of literacy campaigns and the explicit prohibition of using indigenous languages of Guatemalan origin, such as Chuj, Mam, and Q'anjob’al, were introduced under Governor Victórico Grajales’s administration (1932 to 1936). The purpose of these programs was to emphasize the boundaries between both nations by “Mexicanizing” the indigenous inhabitants settled in the border (Hernández Castillo, 2001).

In Guatemala, the modernizing project was exclusionary, racist, and centralized; the State was absent in regions inhabited by indigenous populations, except for a ten-year parenthesis from 1944 to 1954, inspired by the so-called October Revolution. This movement led to the first free elections in the country and initiated a period of modernization in favor of populations in great need. Beyond this, far from promoting their development, the Guatemalan State kept indigenous peoples in conditions of total marginalization. Social inequality led to the creation of different battlefronts by various sectors of Guatemalan society.

A long revolutionary process began in the center and east of the country in 1960, which demanded structural changes in terms of equality and social justice. The Guerrilla Army of the Poor arrived in the Chuj region in the early 1980s; it was then that the Guatemalan army focused its counterinsurgency strategy, which resulted in devastating casualties due to the massacres committed against indigenous peoples, especially the Chuj people (Falla, 2011).

The “scorched earth” policy forced the displacement of Chuj, Mam, and Q'anjob’al peoples to Mexico, who were safe from the Guatemalan army by crossing the border. The Chuj sought protection in Mexican communities founded by their ancestors, such as Tziscao. Refugee camps were also established in the municipalities of La Trinitaria, La Independencia, Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Frontera Comalapa, Bella Vista del Norte, and Amatenango de la Frontera (Hernández et al., 1993). The Federal Government, via the Mexican Refugee Commission (COMAR) and financially supported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the World Food Program, developed assistance programs to help the refugee population (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, 2013).

Kauffer (2002) states that, by 1984, there were 45,000 Guatemalan refugees in Chiapas. The refugees, most of them from indigenous peoples, were relocated to Campeche (two camps for 12,313 refugees) and Quintana Roo (three camps for 6,000 refugees) that same year. After these relocations, 20,468 refugees were officially recognized in Chiapas (Ruiz Lagier, 2015).

By the late 1980s, the refugee population in Chiapas had dispersed in response to the need to make a living, many of them in response to the demand of labor for the opening and occupation of land by Mexican farmers and coffee growers (Hernández et al., 1993, pp. 88-95). By then, 120 refugee camps were located in a large area of the Chiapas border in the municipalities of Las Margaritas, La Independencia, La Trinitaria, Frontera Comalapa, Bella Vista del Norte, and Amatenango de la Frontera (Hernández et. al., 1993). The location of these camps had been initially geared toward the needs of escape and refuge, but they were later rearranged due to agreements with local inhabitants that allowed refugees to settle in ejidos or private lands (Hernández et. al., 1993).

Between December 1987 and January 1988, people who remained in these camps were motivated to return to Guatemala, and an agreement was reached with the Guatemalan government in 1992 to allow for the possibility of an orderly collective return of the refugees. In these agreements, the central issue was access to land through different terms depending on the situation of each refugee (Kauffer, 2002)

According to Ruiz Lagier (2006), 23,000 people were repatriated by the UNHCR and the Mexican and Guatemalan governments between 1987 and 1992 (Ruiz Lagier, 2015). The Migratory Stabilization Program ended in 2005. The purpose of the program was to coordinate the return to Guatemala and grant Mexican citizenship to people who decided to stay (Ruiz Lagier, 2015). As a result, the settlements inhabited by Guatemalan refugees and their descendants were made up of naturalized Mexicans, Mexicans by birth (children of former refugees), and Guatemalan immigrants.6

In 2007, the Chuj were present in at least 36 villages in the Lagos de Montebello region of Chiapas, a space adjacent to the Guatemalan Chuj area (Limón Aguirre, 2009). In 2010, according to INEGI, 1,458 Chuj, 5,769 Q'anjob’al, 5,450 Mam, and 453 Jacaltec inhabitants were registered in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, most of them from villages and cooperativas in the departments of Huehuetenango, El Quiché, Alta Verapaz, and El Petén (Ruiz Lagier, n.d.).

PERMANENCE AND RETURN: NEW BORDER DYNAMICS

In the previous section, we referred to a process through which families and communities were forced to abandon their homelands in Guatemala. This forced displacement entailed the temporary loss of their physical link with their space and, consequently, the impossibility of acting upon this bond. Haesbaert (2013) calls this process deterritorialization, emphasizing the diminishing power over space. It stresses that the process involves not only the abandonment of territory but also its precariousness. Such was the case for the Chuj refugees, who from a subservient and precarious position, were deprived of the control that they exercised over the space they were forced to abandon. Nor did they have authority over the places they lived in provisionally.

As described by the same author, their movement resulted in a deterritorializing effect associated with a deterioration of their material living conditions and a total lack of control over their homes, lands, or any place where they came as refugees. Hiernaux and Lindón (2004) point out that deterritorialization takes place when there is no room for a secure link between the individual and the space they inhabit: there is no history and no thought of a future there, and the situation is experienced as transitory.

The return to Guatemala of part of the Chuj population who were refugees, as well as the decision to stay in Mexico of another part, resulted in parallel development referred to as reterritorialization by Hiernaux and Lindón (2004) it describes the process of constructing one’s future in a specific space, of assuming oneself as profoundly anchored to that space as an inhabitant. Therefore, for example, for people who returned to Yalambojoch, in the municipality of Nentón, Guatemala, this decision involved reconstructing their ties with the territory and the recovery of affective bonds, as well as the construction of new identity elements. Also, the people who decided to establish themselves permanently in refuge areas experienced a reterritorialization process insofar as they ceased to be only “occupants” of the space and envisioned a project of life involving their permanent residence in the space, where certain advantages were available; they could keep material and symbolic links with their place of origin (ibid.).

This double reterritorialization process resulted in the strengthening and consolidation of a cross-border circuit supported by parental, social, and cultural ties between families and Chuj communities separated by the border. The presence of most ex-refugee populations near the border favored the invigoration of cross-border relations after part of the Chuj population returned to Guatemala. Commercial and family ties, and even labor migration, became stronger (Kauffer, 2002). These elements mobilized relations between inhabitants of Chuj communities, despite the international political divisions.

Based on our fieldwork –carried out in Yalambojoch, Guatemala and Santa Rosa El Oriente, Mexico– we should point out that results indicate that the current cross-border flows of inhabitants from Chuj communities in both countries have configured translocalities as described by Appadurai (1999). For this author, translocalities are an emerging category of human organization where marriage, labor, commercial, and leisure connect circulating populations via different types of “locales”; these locales create communities that belong to specific Nation-States, but from a different point of view, they can be called translocalities (Appadurai, 1999, p. 162).

Family, commercial, labor, and cultural bonds intertwine Chuj populations in each country. Although they belong to different Nation-States, they are translocalities: they emerged in spaces of complex and quasi-legal circulation of goods and people (Appadurai, 1999). They share the backdrop of territorial domains determined by a shared past.

The decision to return to Guatemala by a segment of the refugee population and the decision to stay in Mexico by another segment had the following outcomes: a) the creation of new communities composed of former refugees on the Mexican side; b) family and community reconstructions in Chuj communities located on both sides of the border; c) new movement dynamics for people, as well as merchandise, cultural and material goods; d) the configuration of differentiated citizenship statuses within family groups, communities, and villages, and e) the creation of new migration networks that allowed for transnational mobility.

Border dynamics were strongly marked by the experiences of the refugees, the Mexican naturalization of a segment of the displaced population, and the return of thousands of families to Guatemala. The negotiated search for peace in the region provided opportunities for an assisted and institutionalized return to Guatemala, which allowed thousands of former refugees to return to their country and rebuild their lives. They left behind their experience as refugees, but they acquired a wealth of significant learnings and events, including having children on Mexican soil, some of whom moved with their families back to Guatemala.

As the neighboring country attained peace, the Mexican government began the definitive integration of Guatemalan refugees into Mexican society by developing two programs: the Migratory Regularization Program, which distributed approximately 18,420 certificates of naturalization in 1998, and the Naturalization Program, which granted a total of 10,098 certificates until its closure in 2004 (Comar, 2013).

In returned communities, with financial aid from the European Union, different projects were implemented to achieve the economic integration of these groups of former Guatemalan refugees; these projects involved immediate help to build houses or land to returnee families who lacked property or had lost it during the armed conflict. However, thousands of exrefugees were not taken into account in the official records, and therefore, they missed the benefitss (Association for the Advancement of Social Sciences in Guatemala, 1990). On the other hand, many people who chose to remain in Mexico faced severe difficulties in accessing land and benefiting from State development policies; as a result, they were forced to face discrimination, exploitation, and inequality (Ruiz Lagier, 2018).

The option of returning to Guatemala or settling in Mexico was a dilemma for hundreds of Chuj families. Some of them considered that staying was the best alternative, either because they were afraid of returning to a country that had threatened them or because they envisioned a better future in the country that sheltered them. The words of Andrés Gómez, a former municipal official in Santa Rosa El Oriente, municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, summarizes this situation: “The Guatemalan government asked us to come back, but why would we do that? They did not want us, they persecuted us, they abused us, and the Mexican government told them: “You didn’t want them, now they’re mine” (Santa Rosa El Oriente, personal communication, May 10, 2018).

Santa Rosa El Oriente, a community located near Lagos de Montebello, is one of the towns founded by former Chuj refugees who decided to stay permanently in Mexico, where they partnered to buy land.7 Other families chose to return to Guatemala after finding out about the peace process and that they were very likely to recover their lands. However, the consensus among family groups was not always reached, and divisions emerged in extended families and domestic groups. People from Santa Rosa, for instance, came to the refugee camps when they were very young and preferred to stay now that they had their own family, even when their parents, siblings, or other relatives decided to return to Yalambojoch. In contrast with other groups, people from Yalambojoch recovered their lands because they were communal property, and some villagers returned a few months after they had taken refuge in Chiapas to guard their land and prevent it from being occupied by outsiders.

Circumstances were not the same for all returnees; many of them were relocated to areas determined by the government, which undoubtedly resulted in very different integration processes. Similarly, the Chuj communities living in Mexico have followed different paths in their integration into their new country.

FAMILY RECOMPOSITIONS

This double process in which part of the refugees returned to Guatemala and part of them remained in Mexico led to the configuration of cross-border families (Ojeda, 2009). These families are characterized by the different levels of their social action being developed within the border region; members of these families have different citizen statuses, which determines their ability to move within national territories and in cross-border networks, that is, they are separated by international borders and by divisions occurring within one country (Lerma Rodríguez, 2016).

Inhabitants from the village of Yalambojoch estimate that approximately half of the refugee population decided to return, whereas the rest decided to stay in Santa Rosa El Oriente, Chiapas, and other settlements in the area around the Lagos de Montebello National Park. As a consequence, Santa Rosa, a village of around 350 inhabitants, includes families composed of Guatemalan older adults who were granted Mexican citizenship, their Guatemala-born children who were also naturalized, their Mexico-born grandchildren, as well as Guatemalans who lacked a naturalization certificate. For their part, families in Yalambojoch are composed of grandparents and parents who were refugees in Chiapas and were not granted Mexican citizenship, their Mexican-born children or grandchildren who returned with them to Guatemala, and younger children who were born in Guatemala after their parents returned. Any family may have children or other relatives who decided to stay in Chiapas regardless of their place of birth.

In May 2018, we surveyed 200 Yalambojoch households, which represents approximately 80% of the total population. This exercise revealed that, based on their family links in Santa Rosa El Oriente, San José Belén, or Nueva Esperanza, among other villages in the municipalities of La Trinitaria and Independencia (Chiapas, México), 82% of the interviewed families can be characterized as cross-border. We will now present examples of cross-border families.

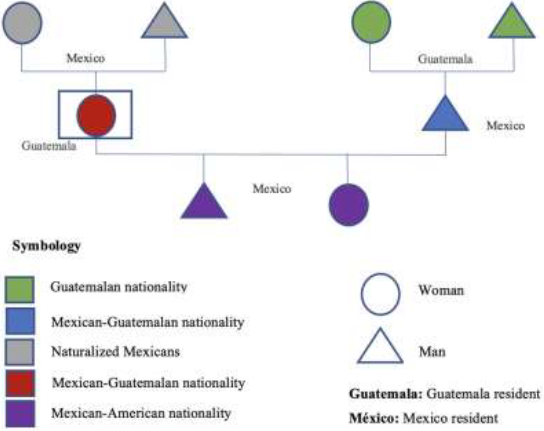

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1. Cross-Border Family Tree of Eulalia Felipe, Mexican-Born and Return Migrant

Eulalia, Miguel, and their two children live in the border. Eulalia’s parents ended up as refugees in the municipality of La Trinitaria during the armed conflict in Guatemala (1960- 1996). They decided to settle in San Lorenzo, a village in La Trinitaria and sought Mexican citizenship. Eulalia and her several siblings were born when their parents were refugees, so they acquired Mexican nationality by birth. Miguel’s parents, also former refugees, decided to return to Guatemala with their Mexican-born children, among them Miguel, because they gave up their Mexican citizenship process.

Currently, Eulalia, Miguel, and their two children live their lives in villages located in both countries. Before becoming parents, Eulalia and Miguel emigrated to the United States for five years, where their two American children were born.

The savings that they obtained during their stay in the U.S. enabled them to open a small restaurant and build a house in El Aguacate, a Guatemalan Chuj village in the municipality of Nentón, where Miguel’s parents live. They also built a house in San Lorenzo (La Trinitaria, Chiapas), where Eulalia’s parents live. The couple made the strategic decision to live in both countries to maintain links with their parents and guarantee Mexican rights for their children, that is, better educational and health services and access to welfare programs, such as PROSPERA. 8

Eulalia and her children spend most of their time in San Lorenzo and travel to El Aguacate on the weekends, where her husband takes care of the family business. During these visits, Eulalia helps her husband in their establishment, and she brings clothes and household items from Chiapas to sell them in El Aguacate. This trip from San Lorenzo, a village on the Mexican side, to El Aguacate, in Guatemala, involves crossing the border, making scales, and using different means of public transportation. Despite that, the commute takes only one and a half hours, given the proximity between the two towns separated by the border.

It should be stressed that not all cases have been successful in maintaining family ties on both sides of the border. There are, of course, cases of radical separations between relatives who ended up in different countries and whose fates were split due to economic or other kinds of difficulties, such as their lack of immigration documents.

We will now present an example of a family who returned to Yalambojoch after 10 years as refugees. Although all of its members live in the village, except for a young man who migrated to Mexico City, they have different citizen statuses.

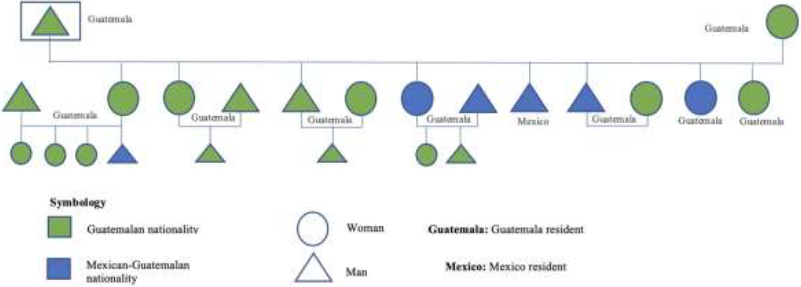

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2. The Cross-Border Family Tree of Juan Jorge, A Former Guatemalan Refugee

Juan and María lived in Chiapas for one decade; in 1982, they fled Yalambojoch along with their four small children (three girls and one boy). During their time as refugees, they had four more children—two boys and two girls—who were Mexican by birth. They decided to return to Yalambojoch to recover their lands. The younger children have dual citizenship; one of them took advantage of this condition and entered the labor market in Mexico City. The rest remained in the village. The three oldest children married Guatemalan women and had Guatemalan offspring. One of the younger daughters has dual citizenship and married a man in the same condition, but their children were born in the village, and they have Guatemalan citizenship only.

The different citizenship statuses within the same family generate social and economic inequalities, as well as possible tensions among its members because it provides different mobility and migration trajectory management options. Those who hold Mexican nationality or dual nationality can aspire to better work alternatives. They have the possibility of reaching the United States border without being deported and try to insert themselves into existing networks of agricultural workers in different parts of the United States.9

Couples whose members have different nationalities (Guatemalan and Mexican) are today common in Guatemala; they often seek that their children be born in Mexico so that they can obtain dual nationality. There are also cases in which the two members of the couple are Guatemalan, but they travel to the city of Comitán, Chiapas, to have their children delivered in Mexican territory.

Young people from Yalambojoch and neighboring villages often try to obtain Mexican citizenship documents even when they were born in the village after their parents returned from the refuge. Although these attempts are not always successful, family and acquaintances support them by certifying that the children were born in Mexico.

On the other hand, the events around the refugee’s experience and their choice to return to Guatemala or stay in Mexico were determining factors in their future; people who acquired Mexican citizenship had the opportunity to migrate beyond the border. Hundreds of young Chuj people are now undocumented migrants in the United States; their networks have expanded to Tennessee, Portland, South Carolina, Mississippi, Missouri, Washington, and Georgia, where they work in agricultural and services activities, such as harvesting tomatoes, grapes, and peppers; raising and processing chickens, or breeding livestock. They are also employed by restaurants as kitchen assistants, although on a smaller scale (Mateo Lucas, Yalambojoch, personal communication, October 12, 2017).

Mexico itself is another important destination for young Chuj from Yalambojoch. Some of them take on circular migration cycles from Comitán, Chiapas, to coffee plantations in the Soconusco, also in Chiapas, and the touristic Mexican Caribbean in Quintana Roo. Mexico City was also a relevant destination, especially for some of the first refugees, and today, young people from Yalambojoch who have a dual nationality have moved to the Santa Fe area in Mexico City, where they work in the construction and restaurant industries.

CROSS-BORDER CIRCULATIONS

As previously stated, villages along the Guatemalan-Mexican border have always been linked by exchange and circulation dynamics. Before the 1990s, Guatemalan families could easily visit Mexican touristic sites or acquire food and domestic products in the city of Comitán, Chiapas, located approximately 70 kilometers from the border and from other urban centers near the border, such as Ciudad Cuauhtémoc. However, these dynamics were affected by increased security at border crossings, such as those in Tecun Umán and La Mesilla in Guatemala and Ciudad Hidalgo and Ciudad Cuauhtémoc in Mexico, where Guatemalan travelers are required to produce official documents (e.g., passport, Mexico’s INE official I.D., Regional Visitor Card, or the Border Worker Visitor Card).

The border crossing in the Guatemalan village of Gracias a Dios, in the Nentón municipality of Guatemala, is across the border from the Mexican village of Carmen Xhan, in the Mexican municipality of La Trinitaria, is the most relevant for most of the Chuj people on both sides of the border. The Lagunas de Montebello National Park and the touristic city of Comitán, in Chiapas, have created mobility circuits in which cross-border families travel with business, leisure, family, and purchasing purposes. Map 1 shows one of the most popular routes used by cross-border families from Santa Rosa El Oriente and Yalambojoch.

Sources: Information: Ma. Teresa Rodríguez, National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, 2018), Municipal Geostatistic Framework. Elaborated by Bulmaro Sánchez Sandoval, AntropoSIG, CIESAS.

Map 1. Routes and Means of Public Transportation Used by Guatemalan Chuj Populations to the Lagos De Montebello Region, Chiapas, Mexico, and Vice Versa

This form of close mobility has given rise to formal and informal transportation circuits and the development and implementation of shorter and less monitored routes by migration authorities.10

The most frequent Mexican destinations for people from Yalambojoch and its surrounding areas are the city of Comitán, San José Belén, and La Unión (Independencia, Chiapas), as well as Carmen Xhan, Lázaro Cárdenas, and Santa Rosa el Oriente (La Trinitaria, Chiapas). San José Belén, Santa Rosa el Oriente, and Unión are places inhabited by former refugee families with whom they have kinship relationships. Mexico City is also an important destination for Chuj people, especially for work.

Commutes among Comitán, Cárdenas, and Carmen Xhan are usually to request medical treatment and consultation and to buy household items, food, and other items. In Yalambojoch, for instance, there are intense border dynamics around commercial exchanges and supply in the Mexican city of Comitán, which is much closer than the Guatemalan departmental capital of Huehuetenango. Local stores in this city sell Mexican products such as milk, detergents, cosmetics, soft drinks, beer, food, and snacks, among others.

Chuj families based on both sides of the border have strong bonds based on parental ties, but their exchanges also include traditional knowledge, sports competitions (especially soccer), cultural and civic events, and religious beliefs and practices. These communities have built bridges recreating their ethnic belonging by celebrating ferias and fiestas patronales, establishing and maintaining kinship and compadre relationships, and even transmitting their language, as in the case of Santa Rosa El Oriente. Family visits from Santa Rosa El Oriente to Yalambojoch are most frequent during Semana Santa (Easter holidays), Mother’s Day, and the fiestas patronales in May and September. During this time, Mexican relatives of Chuj inhabitants share festivities and elect and crown the queen of May and dance to the marimba; during the Holy Week, cross-border families use to have picnics by the Sachilá river and the Laguna Brava, known in Maya as Yolnabaj.

The mythical origin of the Chuj is present in the collective memory of the inhabitants of Montebello, Chiapas, even in villages formed before refugees arrived. Tziscao, a town in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, was founded at least 100 years before the event, when a group of pioneering families from the Cuchumatanes mountains, in Guatemala, settled in the area in search of arable lan (Cruz Burguete, 1998). The Chuj identity in Tziscao refers to their ancestors’ original homeland, in the municipality of San Mateo Ixtatán, Guatemala. This region is still the symbolic referent for Chuj people in Mexico and Guatemala; the town of San Mateo Ixtatán is located in Huehuetenango, in the Cuchumatanes mountains, and it is considered as the guiding cultural center for the Chuj people (Limón Aguirre, 2009, p. 189). San Mateo is its patron saint, a divinity associated with water and rain, whose feast is celebrated from September 18 to September 21. Chuj inhabitants in Chiapas pilgrimage to this place to reiterate their devotion to this saint, pray for the health of their loved ones, as well as to ask for and thank good harvests. These pilgrimages contribute to the affirmation of symbolic and material bonds between the Mexican Chuj and their main identity reference, located in Guatemala.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The refuge and subsequent return to Guatemala of part of the Chuj population entailed the reconfiguration of communities and families that were separated by the border and were faced by new challenges in terms of social, cultural, and economic interactions. Nevertheless, these families and communities have developed communication and interaction strategies in their everyday lives. On the other hand, the international border restricts movement based on economic resources and citizenship status. These factors determine mobility options within and outside both national territories and exacerbate social differentiation within families and communities. Therefore, the border is an obstacle to the equitable and balanced development between border Chuj populations. The migration trajectories of younger generations include incursions into new labor contexts in Mexico and the United States, but the possibilities of these people to travel within these countries depend on their specific citizen status. This limitation has an impact on their horizontal mobility options and, consequently, on the social mobility expectations of their families.

Borders are representations of space that result in different legal statuses and political identities; they refer to the power of States to different individuals based on categories such as legal/illegal, Mexican/Guatemalan, or migrant/resident (De Genova, 2002). However, borders are also spaces of hybridization, circulation, contrasts, and exchanges. In specific contexts, life at the border leads to a transition from one identity to another or to the vindication of several identities at the same time.

Adherence to the Mexican nation did not radically change the living conditions of Chuj communities, who decided not to return to Guatemala. On the other hand, although the Mexican State has enforced exclusionary practices, the Chuj have better health care and educational options in Mexico than their Guatemalan neighbors.

We have argued that the binational Chuj space is associated with a condition of ancestral mobility. In the specific case of Yalambojoch and Santa Rosa El Oriente, space is being configured by kinship relationships across the border despite the differences associated with the different citizenship statuses. In this particular case, the movements and interactions across the border contributed to the vitality and transmission of the Chuj language. This is reflected by the religious celebrations of the Orthodox Christian Church, which has a considerable percentage of Chuj supporters (masses are celebrated using Chuj language), as well as its everyday use at home by children and adults. The use of Chuj female clothing in certain celebrations has also been maintained. Regardless of their nationalities and the policies of each nation-state, these people identify themselves as Chuj.

The different circulation and mobility experiences underwent by the inhabitants of Chuj villages near the border challenge the notion of correspondence between the State, the nation, the territory, and citizenship. Although the ability to travel across borders is limited by the spatial margin allowed by people’s citizenship status, there are forms of domination that transcend such limitations. Cross-border commuting resulting from family, social, cultural, religious, business, and festive motivations transcend the circumscriptions imposed by national states and the condition of citizenship.

The Chuj identity is associated with their roots in a symbolic territory whose main referent is located in San Mateo Ixtatán, Guatemala. Despite the legal divisions, cultural continuities persist and are endorsed. Such is the case of Chuj communities in Mexico and Guatemala (Mejía, 2013), who share a common past and strong family, social, and ethnic bonds that refer to San Mateo Ixtatán, in the Cuchumatanes mountains. This intense traffic network is affected by border security regulations. We consider that policies restricting circulation in this border should be reevaluated so that the cross-border relationships between indigenous peoples such as Chuj, who have traditionally occupied these spaces, can be maintained and strengthened.

REFERENCES

Appadurai, A. (1999). Soberanía sin territorialidad. Notas para una geografía posnacional. Nueva Sociedad, (163), 109-124. Recuperado de https://nuso.org/articulo/soberania-sin-territorialidad-notas-para-una-geografia-posnacional/ [ Links ]

Asociación para el Avance de las Ciencias Sociales en Guatemala. (1990). Política institucional hacia el desplazado interno en Guatemala. Guatemala: Asociación para el Avance de las Ciencias Sociales de Guatemala. [ Links ]

Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (Comar). (2013) El refugio guatemalteco. Gobierno de México. Recuperado de http://www.comar.gob.mx/en/COMAR/El_refugio_guatemalteco [ Links ]

Cruz Burguete, J. (1998). Identidades en fronteras, fronteras de identidades. Elogio de la intensidad de los tiempos en los pueblos de la frontera sur. México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

De Genova, N. P. (2002). Migrant “Illegality” and Deportability in Everyday Life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31(1), 419-447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085432 [ Links ]

De Vos, J. (2002). La frontera sur y sus fronteras: Una visión histórica. En E. Kauffer (Ed.), Identidades, migraciones y género en la frontera sur de México, (pp. 49-68). México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. [ Links ]

Falla, R. (2011). Negreaba de zopilotes. Masacre y sobrevivencia: Finca San Francisco Nentón, Guatemala (1871 a 2010). Guatemala:. Maya’ Wuj-AVANCSO. [ Links ]

Haesbaert, R. (2013). Del mito de la desterritorialización a la multiterritorialidad. Cultura y representaciones sociales, 8 (15), 9-42. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2007-81102013000200001&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es [ Links ]

Hernández Castillo, R. A. (2001). La otra frontera. Identidades múltiples en el Chiapas poscolonial. México: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [ Links ]

Hernández, R. A., Nava, N., Flores, C. y Escaolna, J. L. (1993). La experiencia del refugio en Chiapas. Nuevas relaciones en la frontera sur mexicana. México: Academia Mexicana de Derechos Humanos. [ Links ]

Hiernaux, D. y Lindón, A. (2004). Desterritorialización y reterritorialización metropolitana: La ciudad de México. Documents d’analisi geografica, (44), 71-88. Recuperado de https://ddd.uab.cat/record/1392 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi) (2018). Marco geoestadístico municipal Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mg/ [ Links ]

Kauffer, E. (2002). Movimientos migratorios forzosos en la frontera sur: una visión comparativa de los refugiados guatemaltecos en el sureste mexicano. En E. Kauffer (Ed.), Identidades, migraciones y género en la frontera sur de México, (pp. 215-242). México: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur [ Links ]

Lerma Rodríguez, E. (2016). Guatemalteco-mexicano-estadounidenses en Chiapas: Familias con estatus ciudadano diferenciado y su multiterritorialidad. Migraciones Internacionales, 8(3), 95-124. [ Links ]

Limón Aguirre, F. (2009). Historia chuj a contrapelo. Huellas de un pueblo con memoria. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur/Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnología del Estado de Chiapas. [ Links ]

Mejía, L. (2013). Reapropiación del territorio lacustre de Montebello: El caso de un pueblo fronterizo chuj en Chiapas (Tesis de Doctorado en Ciencias Sociales). El Colegio de San Luis, México. [ Links ]

Navarrete, C. (1979). Las esculturas de Chaculá, Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Serie Antropológicas 31. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [ Links ]

Ojeda, N. (2009). Reflexiones acerca de las familias transfronterizas y las familias transnacionales entre México y Estados Unidos. Frontera Norte, 21(42), 7-30. [ Links ]

Piedrasanta, R. (2009). Los Chuj. Unidad y Rupturas en su espacio. Ciudad de Guatemala: ARMAR Editores. [ Links ]

Piedrasanta, R. (2014). Territorios indígenas en frontera: Los chuj en el período liberal (1871- 1944) en la frontera Guatemala-México. Boletín Americanista, 2(69), 69-78. [ Links ]

Ruiz Lagier, V. (2006). Ser mexicano en Chiapas. Identidad y ciudadanización entre los refugiados guatemaltecos en La Trinitaria, Chiapas. México (Tesis de Doctorado en Antropología, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social). Recuperado de http://repositorio.ciesas.edu.mx/handle/123456789/110?show=full [ Links ]

Ruiz Lagier, V. (2015). El refugio guatemalteco en México, ¿Proceso inconcluso? En R. Gehring y P. Muñoz Sánchez (Eds.), Educación, Identidad y Derechos como estrategias de desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. II Decenios de los Pueblos Indígenas, (pp. 234- 240). España: Universidad Católica de Murcia. [ Links ]

Ruiz Lagier, V. (2018). Los refugiados guatemaltecos y la frontera-frente de discriminación, explotación y desigualdad. Alteridades, 28(56), 47-57. https://doi.org/10.24275/uam/izt/dcsh/alteridades/2018v28n56/Ruiz [ Links ]

Ruiz Lagier, V. (s.f). Los Promotores de educación como actores claves en la educación comunitaria. El caso de los chujes, kanjobales y acatekos de origen guatemalteco en Chiapas, México, (pp. 1-11). Recuperado de https://es.scribd.com/document/167058911/Los-Promotores-de-educacion-como-actores-claves-en-la-educacion-comunitaria-El-caso-de-los-chujes-kanjobales-y-acatekos-de-origen-guatemalteco-en-Chi [ Links ]

Ulrich, W. y Castillo, V. (2015). Investigaciones arqueológicas en la región de Chaculá, Huehuetenango. XXVIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, (pp. 351-364). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. [ Links ]

3The project was funded by the Institutional Fund for Scientific, Technological, and Innovation Development (FORDECYT) of the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) and it gathered scientists from Mexican and Guatemalan academic institutions: the GEO Center, the Center for Research and Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS), El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF), El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), the Mora Institute, the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE), the Latin American School of Social Science (FLACSO), and the University of San Carlos, Guatemala (USAC). http://www.rtmg.org/

4LMI-Meso is an international cooperation project with contributions by CIESAS, the Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement (IRD), and FLACSO Costa Rica; the project brings together scholars and students from different countries (Mexico, France, and Central America) focused on the areas of mobility, governance, and natural resources in the Mesoamerican Basin.

5In 1895, the Tziscao Chuj inhabitants obtained titles to the lands they occupied as part of the colonization process in the Mexican southeast; they were also given Mexican nationality.

6Both Ruiz (2015) and Hernández et al. (1993) point out that thousands of refugees failed to obtain the certificate of naturalization from COMAR; at the end of the naturalization program, their procedures were still incomplete, and they were left without valid migration documents and a total lack of protection, which is why they have been called the “invisible refugees” (Ruiz Lagier, 2015).

7Other ex-refugee groups were relocated in the border states of Chiapas and Quintana Roo; some of these people and their descendants remain in these territories. In many cases, former refugees remained in Mexico, but without access to their own because they lacked resources to acquire them, so they were forced to swell the ranks of national and transnational migrant workers.

8The PROSPERA social inclusion program was in force during President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, from 2012 to 2018. Its purpose was to contribute to the provision of social rights that would empower people living in poverty through actions aimed at increasing their capacities in terms of food, health, and education. This program provided financial support to families with children or young people of school age enrolled in educational programs who met a series of basic requirements and commitments. See data.gob.mx/busca/organization/about/prospera . Since 2019, under the presidency of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018-2024), this program began to be restructured.

9In Yalambojoch, deportations from Mexico are experienced as a loss of prestige because they are targeted only at people who lack Mexican nationality documents.

1010During the fieldwork phase of the present study (February 2018-March 2019), we observed that this crossing was relatively easy due to the almost inexistent surveillance of migration authorities, but this situation changed drastically in June 2019, when the Mexican government gave in to pressure from the United States to stop migration from Central America by deploying 6,000 National Guard troops to the Guatemalan border.

Received: March 01, 2019; Accepted: August 13, 2019

texto em

texto em