Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.31 México 2019 Epub Feb 05, 2020

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2044

Article

Catalanness to the North and South of the Pyrenees: Social Representations and Cross-Border Cooperation

1Université Catholique de Louvain, Bélgica, pearldiana5@gmail.com

This article explores the symbolic construction of the border by actors in cooperation projects in the cross-border Catalan region. Drawing on Jerome Bruner’s narrative approach (with an emphasis on self-stories and micro-narratives) and the theory of social representations, this work provides an insight into the multi-dimensional relationship between borders and identities, and the connections between social representations and practices that illustrate cross-border aspects. Thus, the key focus of this analysis is to determine how current practices in terms of flows, passage, and cooperation in Europe influence imaginaries and the discursive construction of the border.

Keywords: Narratives; borders; identity; otherness; Catalonia

El presente artículo se indaga en la construcción simbólica de la frontera que realizan actores de proyectos de cooperación en el espacio catalán transfronterizo. A partir del enfoque de las narrativas de Jerome Bruner (con énfasis en las auto-historias y micronarrativas) y la teoría de las representaciones sociales, nos acercamos a la relación multidimensional fronteras-identidades y a los nexos entre las representaciones y las prácticas sociales que dan cuenta de lo transfronterizo. Constituye, entonces, el eje principal de nuestro análisis determinar de qué manera las prácticas de flujo, pasaje y cooperación que se consolidan actualmente en el espacio europeo influyen en los imaginarios y en la construcción discursiva de la frontera.

Palabras clave: narrativas; fronteras; identidad; alteridad; Cataluña

INTRODUCTION

The array of metaphors associated with borders –barriers, filters, boundaries, walls, frontiers, lines, but also junctures, crossroads, resources, bridges, links ( Kolossov, 2005 ; Anderson, 2001 ; O’Dowd, 2001 )– reflect a shift in meanings under the influence of globalization and new perspectives in border studies, known as postmodern ( Kolossov, 2005 ; Newman & Paasi, 1998 ), and reveal the complexity of any reflection on the social, cultural, and economic effects of an object that can refer both to a line separating Us from the Other and to contact and hybridization.

Various authors (Kolossov & Scott, 2013; Newman, 2006 ; Paasi, 1999 , Konrad, 2014 ) agree on the predominance of borders –in terms of their symbolic dimension and as an object that refers to a materiality, a spatiotemporal relationship– in intellectual and scientific thinking, namely, in the cultural production of today. We have witnessed a proliferation of discourse on the “line” or “barrier” that has manifested itself in iconography, legislation, films, novels, and education ( Paasi, 1999 ; Newman & Paasi, 1998 ). I agree with Konrad (2014) that “both borders and cultures have been diminished ostensibly through globalization, yet both borders and cultures are now more evident, real, powerful social constructs in the twenty-first century” (p.45).

In a European context, marked by increased cross-border trade, a multiplicity of cooperation projects at different levels and scales, and the free movement of capital, goods, and persons, I turn my attention to borders. This demonstrates a reframing of national borders and a rethinking of their value as boundaries. This is why the focus of this study lies in the effects of these new practices, realities, and understandings in the symbolic construction of the border, one’s own identity, and the Other in the cross-border Catalan region.2 This designation encompasses the historically Catalan territories located close to the border between France and Spain, established in 1659 by the Treaty of the Pyrenees

My starting point is a vision of the cross-border region as an everyday living space and a locus for the meaningful relationship between identity and otherness. The main focus of the study is to move toward an analysis and understanding of the links between social practices and representations, with an emphasis on the subjective dimension of the border, which illustrates the imaginaries and is reflected in the social interactions and stories constructed collectively by the individuals that inhabit, produce, and reproduce the cross-border region – hence my interest in the border poetics focus and an analysis of individual and collective narratives (self-stories, micro-narratives) as keys for interpreting the multi-dimensional border-identity relationship and the shaping of (cross-)border identities.

This study falls under the framework of the theoretical perspective of social representations, understood as common-sense knowledge, a socially developed form of knowledge that contributes to the social construction of reality ( Jodelet, 1989 ). The social representation theory allows us to examine in depth the dialogues and self-discourse through which subjects from the Catalan (cross-)border region describe the Other and forge/reinforce their own image, while gaining access to discursive aspects of representations associated with the border.

Catalan culture has demonstrated great resilience, and to that effect the vernacular language has played a pivotal role. This defiant disposition translates into Catalans’ capacity to transcend the numerous Gallicization and Hispanization processes they have faced throughout history, and participate in the national dynamics of France and Spain without losing their arrels (roots). For this reason, various authors ( Keating, 1996 ; Prat de la Riba, 1978 ) have argued that in Catalonia, we find ourselves before a stateless nation.

I believe that the identity implications and the rich history of the Catalan border firmly support the relevance of this exploration of the way in which European initiatives for territorial cooperation shape the symbolic construction of the border and the relationships between identity and otherness in the Catalan cross-border region.

EUROPE: FROM PRAISE FOR TO A RECYCLING OF BORDERS

There is a consensus that the growing interest in borders (whether state, political, economic, social, or cultural) can be interpreted, in part, as a counter-discourse to the vision of a deterritorialized, borderless world proposed by the precursors of neoliberal globalization. “In the face of the abuses of globalization, a denial of political and geopolitical aspects […], we are rediscovering borders that had not disappeared, only become less visible, in particular in the European area of free movement,” ( Foucher, 2016 ).3

I agree with Newman (2006) that discourse on a borderless world is both disciplinary and geographically localized. In his view, economists and professionals in new information and communication technologies –or cyberscholars– have been the purists and precursors of these proposals, while geographers, sociologists, political scientists, and international lawyers have also shown a degree of skepticism. From a spatial perspective, Newman concludes, the borderless world is a Western and, specifically, a Western European construction. Amilhat-Szary and Fourny (2006) also problematize Europe’s responsibility in this regard, as both the cradle of the Westphalian notion of borders and the region that has made most progress in the world toward eliminating internal borders and enabling the free movement of capital, goods, and persons.

Regarding the European Union’s experience of cultural and economic integration, O’Dowd (2001) claims that it is more a case of reconfiguring state borders than eliminating them. He quite rightly highlights that the aim of the European project is not to abolish borders but rather to pursue “new, more democratic, and consensual ways of managing border change to replace the long European tradition of inter-state war, violence and coercion. It seeks to replace cross-border conflict with cooperation,” ( O’Dowd, 2001, p. 68 ).

State borders have become a recurring subject in social thought, sometimes at the expense of other ways of differentiating or structuring space. This phenomenon can be explained by the severe aftereffects and disruptive impacts of such barriers, or in light of the numerous initiatives that seek to transcend them.

Various authors ( O’Dowd, 2001 ; Newman, 2006 ; Garton Ash, 1999 ) mention the volatility and proliferation of state borders as distinguishing features of the 21st century. In History of the Present, a collection of piercing and ironic essays on the complexity of geopolitical changes in Central and Eastern Europe since 1990, the journalist and historian Timothy Garton Ash (1999) clearly describes the impact of these numerous spatial reconfigurations on border populations: “The old man says he was born in Austro-Hungary, went to school in Czechoslovakia, married a Hungarian, worked most of his life in the Soviet Union and now lives in Ukraine. ‘Travelled a lot, then?’ asks his interviewer. ‘No, I never moved from Mukachevo,’” ( Garton Ash, 1999, p. 379 ).

From Border Studies to Border Poetics: The Border as a Representation

Although border studies constitute a consolidated disciplinary field, new ways of examining borders are currently being systematized. One example of this is border poetics ( Wolfe & Schimanski, 2007 ; Kurki, Kaskinen, Laurén, & Ristolainen, 2014 ), which focuses on analyzing symbolic productions and discourse revealing the meanings attached by state actors, the border population, and society at large to the border, crossing over, and the Other.

Various authors ( Bamberg, 2007 ; Cabecinhas & Abadia, 2013 ) agree that in recent years there has been a “narrative turn” in human and social sciences. This multiplicity of proposals and approaches derived from narrative and discourse from everyday interactions, conveyed through language and shared in a communication process, can only be understood if “narratives” are embraced as legitimate forms of social knowledge.

Bamberg (2007) attributes this renewed interest in the narrative paradigm to two key theoretical-methodological reasons: on the one hand, its person and subjectivity-centered approach “interested in the exploration of narratives as personal ways to impose order on an otherwise chaotic scenario of life and experience” (2007, p. 2); and on the other, its social orientation centered on “the communal ordering principles that seem to be handed down from generation to generation in the form of communally-shared plot lines, making their way into the lives of ordinary people and their stories of personal experience,” ( Bamberg, 2007, p. 3 ).

Within the tradition of border studies, works by authors such as Kolossov, O’Loughlina, and Toal (2016) , Meinhof and Galasinski (2000) , and Newman and Paasi (1998) on national narratives (political, media, and popular) that legitimize borders illustrate the importance of identity discourse in the social construction of space, the consolidation of material and symbolic borders, and cultural differentiation processes. “The study of narratives and discourse is central to an understanding of all types of boundaries, particularly state boundaries. These narratives range from foreign policy discourses, geographical texts and literature (including maps), to the many dimensions of formal and informal socialization which affect the creation of socio-spatial identities” ( Newman & Paasi, 1998, p. 201 ).

One of the precursors of these new approaches in social sciences was the American psychologist Jerome Bruner (1990 , 1991 , 2004) , according to whom “one of the most ubiquitous and powerful discourse forms in human communication is narrative. Narrative structure is even inherent in the praxis of social interaction before it achieves linguistic expression” (1990, p. 77). For Bruner, it was above all about understanding what personal narratives reveal about the social environment and collective history. As a result, it is understood that the main objective is not to determine how stories are co-structured as texts but how they operate in the construction of social reality.

It is well known that analyzing narratives (autobiographies, everyday stories, myths, and dreams) and discourse (political, professional, media, and identity) is an empiricist approach and a reflection on social representations. This is explained by the key role played by communication ( Moscovici, 1961 , 1989 ; Jodelet, 1989 ) in studying representational phenomena. Communication, therefore, acts as a hinge or vehicle between the individual dimension of cognitive operations and the social dimension of the pooling of these meanings, revealing both the social and cultural nature of the representation.

Social representations are of great topical interest and highly useful to explain social mental productions in their various forms: world theories, beliefs, myths, fabrications, ideologies, and dogmas. Understood as common-sense knowledge that has been socially developed and shared, social representations lie between scientific knowledge and spontaneous knowledge, by virtue of their structure and complexity, and as a result become a sui generis science and a system of notions aimed at discovering and organizing social reality ( Jodelet, 1989 ).

Working on the assumption that all realities are represented, communicated, reconstructed in the cognitive system, and integrated into the value systems of individuals, various authors ( Moscovici, 1961 , 1989 ; Jodelet, 1986 , 1989 ; Abric, 2001 ; Banch, 2000 ) agree that this appropriated and restructured reality constitutes reality by excellence for individuals and social groups. This leads us to the interaction between the mental and material aspects ( Jodelet, 1986 ) of social representations, such that they are not only objects constructed mentally, but symbolic constructions that become a guide for action and may translate into behavior. In keeping with Robert Farr (1984) , rather than “opinions on,” “images of,” or “attitudes toward,” social representations construct reality in their own right.

Considering the border as an object of representation leads to a reflection on crossborder aspects and their implications in forming cultural identity. Border regions, as zones of transition, exhibit complex spatial characteristics and cultural signs that point to a dialectic of continuity and discontinuity, a zone of interaction or third space4 that stands in contrast to the physical boundary represented by the borderline. Konrad (2014) suggests that imaginaries that span borders are far more persistent in the 21st century, on account of the fluidity, accessibility, and malleable and extensive nature of cultural productions.

This line of thinking, which views the border as a space in which cultures come together and a rhizomatic identity can be constructed, is also found in Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation. From this perspective, errantry is no longer an uncontrolled impulse of abandonment, nor does it proceed from renunciation or frustration, but rather from a need to find the Other. “That is very much the image of the rhizome, prompting the knowledge that identity is no longer completely within the root but also in Relation,”5 ( Glissant, 1990, p. 31 ).

I agree with Anthony Cohen (2000) that notions of border and identity are two key concepts with mutual implications. Cross-cultural mobility and interactions between human populations or groups separated by a borderline provide fertile ground to question the absolute nature of identity formulations so that a unique, essentialized identity may, eventually, become a multiple, plural identity.

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

There is a consensus that the study of social representations calls for various techniques and methods of analysis, such as laboratory and field experimentation, questionnaires, interviews, participant observation, ethnography, concept maps, free word association, and document and discourse analysis ( Jodelet, 1989 ; Abric, 2001 ; Ibáñez, 1994 ).

Denise Jodelet (1989) emphasizes the complexity of research on social representations based on the perpetual tension between the psychological dimension and the social dimension in studying representational phenomena. Jean Abric (2001) , on the other hand, identifies two major methodological problems in studying social representations: collecting representations and analyzing factual material. From his perspective, studying a representation means, above all, determining the constitutive elements of the central nucleus. This consideration is based on the composition of social representations per se: content (information and attitudes) and organization (the field of representation, which is in turn composed of a central nucleus and peripheral elements).

This structural approach has indisputable methodological implications. Indeed, any analysis of representations requires the use of methods that identify these constitutive elements and, at the same time, reveal their internal structure and organization. A multimethodological approach to representational phenomena is inevitable and responds to a threefold objective: a) to identify the content of the representation; b) to study the relationships between its elements, and their relative importance and hierarchy; and c) to determine the components of the central nucleus ( Abric, 2001 ).

To achieve these objectives, various methods were employed in this study, including discussion groups, questionnaires and interviews, which focused on subjects’ verbal or figurative expression regarding the object represented: the border. Following Jerome Bruner’s narrative approach, I also collected personal and spontaneous stories about individuals’ own direct and/or indirect experiences of the border.

An important precursor to this research can be found in Considère and Leloup’s (2017) work on local cross-border dynamics in the Franco-Belgian dyad, and specifically in the Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai Eurometropolis. The focal point for my proposal seeks to gain deeper insight into the connections between, on the one hand, social practices that reflect the border and cross-border aspects, and on the other, subjects’ representations of the border itself, their own identity, and their relationship with the Other.

This work is based on the assumption that the border is also a social construction, a set of practices and discourses that go beyond the border region and permeate the rest of society. I agree with Paasi (1991) that the production and reproduction of borders constitutes the process by which territory is produced in its institutional and symbolic dimensions. This gives rise to the idea of the (cross-)border region as a lived, perceived and appropriated space, but above all, one that reveals meaningful practices, narratives constructed collectively, and links and ruptures in identities.

The territorial framework for the study is the cross-border Catalan region, comprising historically and culturally Catalan areas close to the border. On the French side, this includes the comarques6 of Northern Catalonia, with their prefecture in Perpignan, and on the Spanish side, the comarques of the province of Girona and part of Cerdanya. This study was conducted specifically in the towns of Perpignan and Laroque-des-Albères (France) and Girona and Olot (Spain), and is centered on the dynamics associated with cross-border cooperation, defined in this area as cross-thematic and economically significant.

To conduct the study, four cooperative development projects were selected in the crossborder Catalan region: CCI Pirineos-MED (Pyrenees-Mediterranean Chambers of Commerce and Industry); The Spur ETACEC (Creative Europe Cross-Border Contemporary Art Space); Ciudades 3.0, a laboratory for future cities; and the citizens’ initiative for the twinning of the communities of Bagá (Spain) and Laroque (France).

The projects were selected on the basis of their territorial impact and the wide range of institutions involved. The sample is made up of the various actors in these projects on both sides of the border. Given that these actors exhibit different levels of engagement in developing these cross-border cooperation projects, two categories of actors were established: those who were directly engaged (manager, public administration officials, specialists, experts) and those indirectly engaged (target population and staff from associated institutions).

I asked the following operational questions: “How do the different groups of individuals, who are engaged in cross-border cooperation projects to varying degrees, conceive of the border, their own identity and their relationship with the Other?” and “What links can be established between this representation and their direct and indirect experiences of the border?”.

The instruments were selected purposefully based on each actor’s category. Responsive interviewing ( Rubin & Rubin, 2005 ) was used with actors directly engaged in developing cross-border cooperation projects. This type of interview enables an in-depth analysis of a subject based on a detailed exploration of motivations and experiences. “[…] Responsive interviewing is intended to communicate that qualitative interviewing is a dynamic and iterative process, not a set of tools to be applied mechanically […]. Qualitative research is not simply learning about a topic, but also learning what is important to those being studied” ( Rubin & Rubin, 2005, p.15 ). The particularity of this qualitative technique lies in the equal, honest, and empathetic relationship between the interviewer and interviewee, which for the researcher poses the challenge of learning to see reality through the Other’s eyes.

For the second category of actors (those indirectly engaged in cross-border aspects: the target audience, staff from associated institutions), I worked essentially from a questionnaire administered to gather opinions from a much broader population with other levels of responsibility in implementing cooperative projects. The questionnaire comprised 16 mostly open-ended questions to allow the interviewees to express themselves freely: six examined the issue of Catalan identity and their relationship with the Other, four concerned the delineation, characteristics, and functions of borders in today’s Europe, and the rest served to triangulate the information obtained.

Although questionnaires have been systematized, from the outset, as one of the quintessential methods to research the content and structure of social representations, I agree with Considère and Leloup (2017) on the complexity of recording representations using questionnaires, as the aim is for individuals to express the very essence of their opinions.

In this quest for a discursive reconstruction of the border, I also turned to what could be termed border narratives, a proposal based on the tradition of border poetics and an analysis of literary, political, and historical discourse, novels, travel literature, personal accounts, and newspaper articles as support or text corpora for such discourse. The focus in this study is on individuals’ personal stories with respect to the border and their relationship with the Other –in other words, the textual dimension of their own experience put into words.

Based on the idea that individual and collective meanings and identities are renegotiated as subjects recount their lived experience in an exercise in recapitulation, like Jerome Bruner (1990) , I have worked on the assumption that telling a personal story is equivalent to reconstructing and reconceiving oneself individually and collectively. As a result, my interest turns to what personal stories reveal about the social environment and collective history.

CATALANNESS NORTH AND SOUTH OF THE PYRENEES: CROSS-BORDER CULTURES AND IDENTITIES

Just like with borders, there is no single definition of what constitutes a cross-border aspect. Kireev (2015) notes that in the social sciences there is no single, generally accepted concept of a cross-border aspect, and consequently this could be defined in terms of “cooperation,” “interaction,” “region” or “territory.” In this sense, a cross-border aspect may be anything that occurs in the border region when the border does not seek to suppress practices and feelings of belonging ( Amilhat-Szary & Fourny, 2006 ); a system of interaction between actors at different scales and magnitudes, involving both governments and local populations ( Kireev, 2015 ); any form and variety of possible contacts involving contiguous parts of territories (their populations, infrastructure, resources) of two or more neighboring states ( Pestsov, 2015 ); or a process by which different spaces are integrated and a new region is constructed by recycling the border, such that what was a barrier is transformed into a resource ( Leloup & Moyart, 2006 ).

The process by which the European Union has institutionalized this form of cooperation can be traced back to one founding document: the European Outline Convention on Transfrontier Cooperation between Territorial Communities. This framework convention, adopted in Madrid on May 21st , 1980, recognizes the potential of territorial communities in development and promotes cross-border agreements between local and regional authorities and the removal of any kind of difficulty that might hinder cooperation.

The consolidation of cross-border cooperation in Europe has strengthened historical ties and developed a connective tissue between a large number of linguistic and cultural regions and communities separated by a border, as is the case in Catalonia.

Catalans on both sides of the Pyrenees mountain range share a common history that goes back over a millennium. On November 7th, 1659, after a 24-year war, the Spanish and French crowns signed the Treaty of the Pyrenees, formalizing peace between the two kingdoms. As part of the agreement, Spain ceded to France the Catalan territories of Roussillon, Conflent, and Upper Cerdanya (the area now known as Northern Catalonia). Although the boundary itself did not appear until 1860 ( Sahlins, 1998 ) as a result of the Bayonne Treaties, the famous Article 42 of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) would justify the promotion of a linear, geometric and rational border, with the mountain range to be considered henceforth the natural border between France and Spain. However, the ratlla, 7 as various authors have shown ( Vilar, 1962 ; Sales, 2004 ) is entirely arbitrary and has nothing to do with nature. Indeed, as Pierre Vilar underlines, nature “has not laid down any plain boundaries at all; it imposes nothing and suggests nothing,” 8 (Vilar cited in Braudel, 1968, p. 380 ).

From that point on, communities that were historically Catalan –on the basis of linguistic convergence and a shared material and immaterial culture (know-how, customs, mythology, legends, histories, and values)– would be split down the borderline. The ratlla divides Us to engender the Other, and both Spain and France were to implement strategies to consolidate, more or less successfully, their nation states.

It follows that the various geographical, mental, social, and media representations of Catalonia –and by extension, of Catalans and the Catalan culture– relate to the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, a historical region of Spain with its own language, culture, and identity. In his monumental work La Cataluña en la España Moderna [Catalonia in Modern Spain], the French historian Pierre Vilar (1962) offers an analysis of the nation phenomenon as “successive crystallizations” and points out that the region is a universe in itself and that “if there are multiple Spains, there are also multiple Catalonias.”

Indeed, the Catalan culture is also present north of the Pyrenees (in France). The inhabitants of this region, known variously as Roussillon, the Eastern Pyrenees, Northern Catalonia,9 and the County (Condado/Comté/Comtat), and which is currently part of the French region of Occitanie (a result of the merger of the Languedoc-Roussillon and MidiPyrénées regions), identify and define themselves as Catalans, and like the Bretons, Corsicans, Basques, Alsatians, Normans, and others, contribute to the great cultural and linguistic diversity of France.

The French government’s recent decision to rename these historically Catalan areas Occitanie has not come without controversy. Various citizen initiatives and activities have demanded that “Pays Catalan” (“Catalan Country”) be included in the name of the merged region. We are, therefore, witnesses to a genuine identity revival process that goes beyond a mere name, and constitutes a resurgence of Catalanness, both to the north and the south of the Pyrenees.10

In his study on state formation and identity on the Catalan border, the distinguished researcher Peter Sahlins (1998) challenges the dominant historical model whereby modern nations, mainly the contiguous states of Western Europe, were constructed from a top-down or center-periphery perspective, in which particular identities are destructured by the imposition on the peasantry of a unified national culture that leads to the progressive abandonment of the traditional language, behaviors, customs, norms, and practices. In this context, Sahlins presents the peripheral nationalism in Catalonia and the Basque Country in the 19th century as two concrete examples that contradict the model of identity construction around Madrid or Paris.

In the case of Catalonia, peasants, craftspeople, and the nobility on both sides of the border shared a common ethnicity and language, through which they defined themselves as Catalan and differentiated themselves culturally from the French and the Spanish. This cultural unity did not disappear over the two centuries following the Treaty of the Pyrenees. The new national border failed to disrupt the continuity of the social relations interwoven across the boundary.

I agree with Benedict Anderson (2006) that nations are above all imagined communities – imagined by an Us that is symbolically constructed in a creative exercise, such that one nation is distinguished from another not by its false or authentic nature, but by the particular nature of the imaginative act.

RESULTS

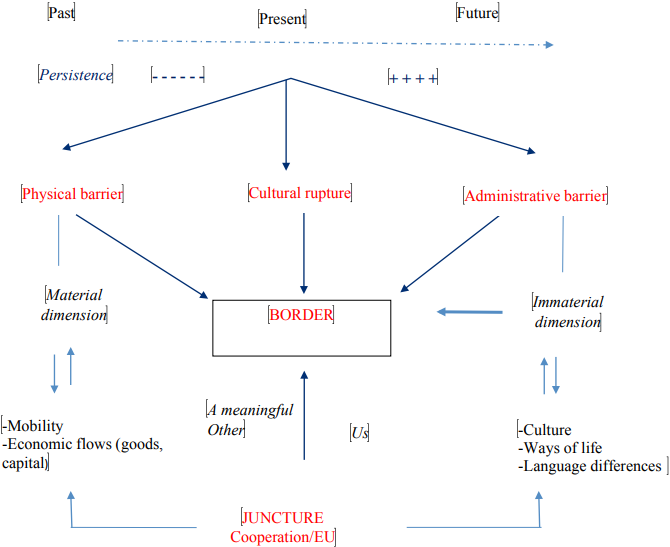

On the basis of a systemic analysis of the content of the responsive interviews conducted with the first category of actors (those directly engaged in cross-border cooperation projects), and their own personal experiences of the border, it was found that the symbolic construction of the object of study is shaped by three meanings associated with the border: a physical barrier, cultural rupture, and administrative barrier.

Evocations perceiving the border as a physical barrier are essentially associated with the historicity of the Catalan border and cross-border practices prior to the establishment of the Schengen Area and the current integration policy of the European Union. In viewing the border as a cultural rupture, explicit references to a perception of the border as a boundary and container of cultural identity come into play, based on an understanding of culture in its broadest, anthropological sense: a set of social practices, lifestyles, a network of meanings, and what a community does and thinks ( Geertz, 1973 ). The border is seen as an administrative barrier in terms of legislative differences and tax burdens, in addition to Europe-wide regulations and standards.

These elements reveal the dual material and immaterial dimension of the border. The intensity, repetitive nature, and semantic density of the evocations relating to cultural and administrative differences become indicators of the figurative nucleus of the representation. What does seem indisputable for the subjects interviewed is that the border –in its immaterial dimension– still exists. At the same time, they do acknowledge that cross-border connections and contacts are much easier today, thanks to the removal of the physical barrier and European cooperation initiatives.

Actors directly engaged in the four projects selected see the role of the European Union, and the financial support it provides for territorial and cross-border cooperation initiatives through the INTERREG program, as a platform that restructures, reconstructs, and reinforces cultural and economic ties in the cross-border Catalan region. This judgment – which has not precluded certain criticism regarding the way the regional organization is managed – leads to the perception that the border has disappeared as a physical barrier, but persists in terms of legislation, tax, and the internal functioning of each country, as well as in the psyche and the imaginary.

Figure 1. Components of the Social Representation of the BorderSource: Own work. Based on the results of the content analysis of interviews and narratives.

Thus, for this category of actors, the symbolic construction of the border is shaped by a recognition of practices and initiatives that transcend the borderline and those that, by contrast, ensure the legal, institutional, and mental persistence of the border, complicating cross-border cooperation. In this sense, two themes or lines of reflection can be identified: one associated with a crossover, a meeting, mobility; and another relating to the different institutional and administrative realities on each side of the border. Also worth highlighting are the striking descriptions or reconstructions of the border based on customs and inspection practices that are no longer applicable at internal borders, as per European regulations currently in force. In this case, the representation is not consistent with real-life practices.

As part of the research, a questionnaire was also given to the second category of actors – those indirectly engaged in cross-border aspects. The respondents were a fairly diverse group: producers and suppliers for small and medium-sized businesses, artists, experts in culture, and the general public. The main criterion used to form the sample was the subjects’ participation in various activities associated with cross-border cooperation projects. I worked with 24 producers and suppliers on the Spanish side, and 11 on the French side, who belonged to a cross-border commercial network; 10 artists from La Volta, an initiative under the cultural cooperation project The Spur-ETACEC; 12 attendees of a multinational exhibition organized by Bolit (Contemporary Art Center of Girona); 11 specialists from the Institute of Culture of Olot (Institut de Cultura d’Olot), which is associated with the Ciudades 3.0 project; and 12 inhabitants of the French commune of Laroque-des-Albères and members of the management committee for the town’s twinning with the community of Bagà. The survey respondents averaged 55 years of age on the French side, and 41 on the Spanish side. Their level of education is fairly high, as most have completed secondary or higher education.

The questionnaire begins with an open-ended question enabling subjects to express themselves freely and spontaneously. Using the border as a trigger word, the objective was to elicit an outpouring of images, words, and evocations.

In a lexical universe of 33 words associated with a definition or conceptualization of the border, 9 are repeated several times. Indeed, 71% of interviewees define the border in terms of a boundary, barrier, separation, wall, obstacle, edge. Other less frequent meanings include another culture, customs formalities, taxes. Only two subjects on the French side (Northern Catalonia) evoked ideas relating to crossing or physically overcoming the barrier: nothing, discovery, crossing point.

The roles attributed to today’s European borders by the actors surveyed can be organized hierarchically on the basis of an inside/outside relationship that was implicit in the discourse and refers to the internal and external borders of the European Union.

For this second group, in contrast to actors directly engaged in cross-border cooperation projects, the border’s material dimension is more persistent, and is associated with control and differentiation. Nonetheless, a significant number of respondents acknowledge that borders lack functionality within the European Union, while stressing the role played by external borders in terms of separation and protection. Within this category, a vicarious knowledge of reality – that is, information obtained through the media, social discourse, or cultural consumption (a perception of national security, international conflicts, and the current migrant crisis, with the resulting emotional charge) – seems to predominate in the symbolic construction of the border.

As part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to give two examples of a “typical border”. The most frequently mentioned borders, both on the French Catalan and Spanish Catalan side, provide an indication of the respondents’ immediate surroundings and cultural references, and international geopolitical conflicts. In order of frequency, the following responses were collected: the border between France and Spain (mentioned 32 times); Andorra, France and Spain (16 times); Spain and Portugal (12 times); in addition to Ceuta and Melilla (12 times), Israel and Palestine (9 times); Mexico and the United States (7 times); and North Korea and South Korea (4 times).

Survey respondents on the French side identified the following factors that promote stronger ties between Northern and Southern Catalonia: the TGV (high-speed train), citizens’ associations, and historical cooperative relations. On the other hand, the Jacobinism of the French government and a continuing shortage of cross-border exchanges and contacts were cited as distancing factors between the two Catalonias. For Southern Catalans, shared cultural roots, physical and linguistic proximity, cuisine, trade, and the European Union hold the key to achieving closer ties between the two regions. Conversely, cultural differences (behaviors, ways of life), dissimilarities in the status of the Catalan language (bilingualism and diglossia), different political and administrative realities, and the economic gap (disparity in taxes and purchasing power) hinder cross-border cooperation.

The analysis of the interviews and surveys conducted with actors directly and indirectly engaged in cooperation projects has shown that individuals’ different social practices and experiences of the border and cross-border aspects have an impact on the way they are represented.

Actors with a direct impact on the development of cooperation projects and who, as a result, maintain close and systematic relations with institutions and individuals from borderlands, believe the border has been overcome in its material dimension, or in other words, as a physical barrier. These actors’ comments feature an abundance of references to a single area, free movement, and a willingness to work together. At the same time, these actors have a much greater awareness of the inherent diversity of the area, the different cultural and administrative practices, and the difficulty of finding a common language, coordinating efforts, and promoting joint initiatives.

References to crossing the border and cross-border exchanges are much less frequent among actors from the second category, who view the border in the conventional sense of edge, wall, boundary, and not just territorially or politically but also culturally. This leads us to another dimension of the study: the symbolic construction of the Other and one’s own identity in the cross-border region.

The Symbolic Construction of the Other and One’s Own Identity

Cultural identity is a cross-cutting theme in comments on organizational practices and language and lifestyle differences. The various actors all acknowledge that the close historical and cultural ties between populations north and south of the Pyrenees facilitate local development and cross-border cooperation. In this context, Us and the Other are configured differently depending on the locus of enunciation –in other words, the position from which the researcher asks about the reality and the location of the individuals who answer. Catalan culture is not a single unit experienced in the same way on both sides of the border. The Us of the Autonomous Community of Catalonia excludes, generally speaking, not just Spaniards but also Northern Catalans on the basis that “they are French.” Meanwhile, the Us of Northern Catalonia is shaped based on a distinction with respect to the French Us, of which Northern Catalans do however consider themselves an integral part. Although an explicit recognition of Southern Catalonia as an identity reference is notable among Northern Catalans, there is also a clear desire for differentiation.

In a free word association exercise, respondents on each side of the border were given three trigger words –Spain, France, and Catalonia– and asked to spontaneously associate three words with each. The information gathered reveals a complex semantic universe and bears the stamp of the political and social realities of respondents. Some frequently recurring evocations tie in with the way various issues are dealt with by national and international news outlets, calling for a reflection on the links between social representations and media representations.

In a semantic universe of 41 words that respondents from the Autonomous Community of Catalonia associate with Spain, various semantic fields are identifiable: monarchycentralism (31 times), backwardness (23 times), unlawfulness-corruption (17 times), but also sun (14 times), culture (12 times), cuisine (8 times), and nation (6 times). The presence of terms with a strong negative connotation cannot be understood without placing them in the context of Catalonia’s current sociopolitical situation, the consolidation of the independence movement, and the tension between Catalan authorities and the central Spanish government. This is necessarily echoed in the voices of citizens.

In the sociodemographic data collected in the questionnaire, 16 of the 45 survey respondents identified Catalonia as their country of origin and 2 reported Catalonia-Spain. Associating Spain with unlawfulness and corruption is also a response to the recent institutional crisis in Madrid and the corruption scandals involving various Spanish politicians, which have featured widely in the national and international press.

Out of a total of 47 terms associated with France, some stand out on account of their frequency and intensity: France is Europe, culture, cuisine, glamour, Paris. The perception or description of Catalonia given by the survey respondents illustrates the complexity of the identity issue and the sociopolitical situation of this autonomous community in Spain.

The territorial frameworks for Catalan identity construction from the south exclude communities north of the Pyrenees: “That’s not Catalonia, that’s France.” An analysis of the most frequent evocations brings us closer to the figurative nucleus of the representation, where the semantic fields of home, culture, prosperity, and work encompass the most significant content with respect to the object represented, and ensure the organization and preservation of peripheral elements.

Figure 2. Representation of Catalonia (Figurative Nucleus) Diagram: Own work based on data obtained from the questionnaire.

As part of a verification question in the questionnaire, subjects on both sides of the border were asked to state which aspects they thought best defined Catalan identity. The answers included language (46%), culture and traditions (42%), the Catalan seny, 11 effort and work (34%).

For those surveyed north of the border, Spain is generally associated with sun and vacations (63%), along with its cuisine (tapas, paella, ham) (32%) and the language, Spanish (28%). One particularity that should be noted is that here, references to various historical events experienced on the Catalan border are much more frequent: the closure during Francoism, the Retirada (“the Retreat”), the Republican exile. Worthy of note is the use of Catalan toponyms to refer both to (Southern) Catalonia and Spain. Culturally and geographically, the subjects do not always clearly differentiate between Catalonia and Spain, although this is not the case as far as language is concerned.

The terms most frequently associated with Catalonia include various toponyms (from the north and the south): Puigcerdà, Cerdanya, Cap de Creus, Perpignan, Le Perthus, Barcelona. All, with the exception of the Catalan capital, are in the cross-border region. Catalonia is also assimilated to its language (Catalan) and folklore (the sardana, castells). To define their own identity, subjects draw on these same elements: the Catalan language and cultural traditions. Catalonia is, thus, described through evocations with highly emotive connotations that make reference to the surrounding environment: “my country,” “my area,” “my home,” “conviviality,” “my childhood,” “friends.” The meanings associated with France revolve around history, culture, centralism, and Paris.

CONCLUSIONS

The populations living north and south of the Pyrenees identify and define themselves as Catalan, but it cannot be denied that two different, albeit convergent, ways of experiencing and embracing Catalanness and interacting with the centers of power, namely Spain and France, are present. The specificity of this relationship determines one’s orientation and attitude (positive or negative) toward the object of representation, which in turn influences behavior and practices.

The complexities and identity implications of borders are particularly visible in Europe, where experience of regional integration, the removal of physical barriers, and numerous cooperation initiatives have not succeeded in erasing borders from the map. Symbolically, they remain in full force. We find ourselves faced with the paradox of a proximity that accentuates certain differences, and the intangibility-legibility of borders.

Regarding the European experience, Meynet and Serrate (1997) had previously noted that perceptions and meanings associated with the border do not evolve at the same pace as institutional reality. In this sense, I should add that although the role of social practices in shaping and transforming representations is indisputable, the emphasis should shift to the interface between the external circumstances and the internal prescriptors of the representation.

Based on an analysis of the results of this study, it was found that practices (in terms of flows, passage, and cooperation) do not determine or have a linear influence on border representations in the cross-border Catalan region. This symbolic construction cannot be dissociated from the history of these communities and their collective memory, or the cadre of socially embedded and transmitted behaviors and knowledge.

The social representations reflect a process of sedimentation and selective accumulation, in which recent and more distant history both play a role – that which is constructed from a subject’s direct experience (reality as directly experienced), and that which is received as part of socialization processes, whether primary (from parents and family) or secondary (from schools, the community, and membership groups). As generators of meanings, individuals play an active role based on a dialectical relationship established between their daily interactions, their experiential universe, and the conditions of their social environment. So it is that the border becomes that porous and physically illegible expression of European integration, yet also a cultural rupture and barrier.

In my view, considering the cross-border Catalan region as an identity and multidimensional space means precisely that: recognizing individuals as competent producers of the space while placing an emphasis on social actors and their interactions and practical experiences of the border and cross-border aspects. It was observed that these experiences illustrate the subjective dimension of the border and have a bearing on the different ways of reconstructing the border discursively and symbolically.

Although new practices in Europe may not directly determine social representations of the border and cross-border aspects, they do shape these representations. Indeed, representations are shaped within a complex dynamic of social practices, hence their capacity to generate new behaviors and relationships. Furthermore, the way in which representations are transformed by practices is closely tied to subjects’ perception of their consistency and permanent or temporary nature. This may serve as a spark for future research on the impact of local-level Europeanization processes on the cross-border Catalan region.

REFERENCES

Abric, J. C. (2001). Prácticas Sociales y Representaciones. México: Ediciones Coyoacán. [ Links ]

Amihat-Szary, A. Y Fourny, M. (2006). Après les frontières, avec les frontières. Nouvelles dynamiques transfrontalières en Europe. France: Editions de l’Aube. [ Links ]

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Anderson, J. (2001). Towards a theory of borders: states, political economy and democracy. Anales, (26), 219-232. [ Links ]

Bamberg, M. (2007). Narratives-State of the Art. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. [ Links ]

Banch, M.A. (2000). Representaciones sociales en Venezuela: la apuesta al cambio. En Develando la cultura. Estudios en representaciones sociales. Jodelet, D. y Guerrero, A. (Coord.), (pp 89-108). México: UNAM, Facultad de Psicología. [ Links ]

Bhabha K., H. (1994). The Location of Culture. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Braudel, F. (1968). La Catalogne, plus l'Espagne, de Pierre Vilar. Annales, (2), 375-389. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, (18), 1-21. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (2004). Life as Narrative. Social Research, (3), 691-710. [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R. y Abadia, L. (Edit.). (2013). Narratives and social memory: theoretical and methodological approaches. Portugal: University of Minho Braga. [ Links ]

Castex-Ey, J. F. (2008). L’Eurodistrict de l’Espace Catalan Transfrontalier: une identité géopolitique en construction? (2), 1-4. Recuperado de http://recerc.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2008/10/recerc-2-article-jf.-castex-fr.pdf [ Links ]

Cohen, A. (2000). Signifying Identities. Anthropological perspective on boundaries and contested values. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Considère, S. y Leloup, F. (2017). Comment interroger la frontière par les représentations sociales. En Considère S. y Perrin, T. (Edit.). Frontières et représentations sociales. Questions et perspectives méthodologiques. Académia l’Harmattan. [ Links ]

Council of Europe (1980). European Outline Convention on Transfrontier Cooperation between Territorial Communities. Madrid: European Treaty Series [ Links ]

Farr, R. (1984). Social representations: Their role in the design and execution of laboratory experiments. En Farr y Moscovici, S. (Edit.), Social Representations. Cambridge : University Press/Paris Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. [ Links ]

Foucher, M. (2016). Entretien dans le cadre de la conférence géopolitique Diploweb.com «A quoi servent les frontières?» Recuperado de: https://diploweb.com/M-FoucherGeopolitique-des.html [ Links ]

Fuentes, C. (1985). Gringo Viejo. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Garton Ash, T. (1999). History of the present. London: Allen Lane. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (1973). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Glissant, E. (1990). Poétique de la Relation. Poétique III. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Ibáñez, T. (1994). Representaciones sociales, teoría y método. Psicología social construccionista. México: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1986). La representación social: Fenómenos, conceptos y teoría. En Moscovici, S., Psicología Social II. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1989). Les Représentations Sociales. France: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Keating, M. (1996). Nations against the State. London: St. Martin’s Press. [ Links ]

Kireev, A. (2015). State Border. En Sevastianov, S., Laine, J. y Kireev, A. (Edit.), Introduction to Border Studies (pp. 98-117). Vladivostok: Far Eastern Federal University. [ Links ]

Kolossov, V. (2005). Etude des frontières: approches post-modernes. Diogène, (210), 13- 27. [ Links ]

Kolossov, V. y Scott, J. (2013). Selected conceptual issues in border studies. Belgeo (1) [online] Recuperado de http://belgeo.revues.org/10532 [ Links ]

Kolossov, V., O’Loughlina, J. y Toal, G. (2016). The rise and fall of “Novorossiya”: examining support for a separatist geopolitical imaginary in southeast Ukraine. Post-Soviet Affairs, 1-21. Recuperado de https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296478265 [ Links ]

Konrad, V. (2014). Borders and Culture: Zones of Transition, Interaction and Identity in the Canada-United States Borderlands. Eurasia Border Review. Recuperado de http://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp. [ Links ]

Kurki, T., Kashinen, S., Lauren, K. y Ristolainen, M. (2014). Culture Unbound. Journal of Current Cultural Research, 6(6), 1183-1205. Recuperado de http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se/ [ Links ]

Leloup, F. y Moyart, L. (2006). La région frontalière: vers quels nouveaux modes de développement et de gouvernance? En Amihat-szary, A. y Fourny, M. (Edit.), Après les frontières, avec les frontières. Nouvelles dynamiques transfrontalières en Europe, (38- 35). France: Editions de l’Aube. [ Links ]

Meinhof, U. y Galasinski, D. (2000). Border Discourse: Changing Identities, Changing Nations, Changing [online], European Comission-Community research. Recuperado de http://cordis.europa.edu/docs/publications [ Links ]

Meynet, J.L. y Serrate, B. (1997). La frontière: discours et représentations sociales. Du concept théorique à l'image formulée de la fronteire [online], Recuperado de http://www.persee.fr/doc/globe_0398-3412_1997_num_137_1_1378 [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1961). La Psychanalyse Son Image et Son Public. Paris: P.U.F. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1989). Des représentations collectives aux représentations sociales éléments pour une histoire. France: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Newman, D. (2006). World Society, Globalization and a Borderless World. The Contemporary Significance of Borders and Territory. Zurich: World Society Foundation. [ Links ]

Newman, D. y Paasi, A. (1998). Fences and neighbours in the postmodern world. Boundary narratives in the postmodern world. Progress in Human Geography, (22), 186-207. [ Links ]

O’Dowd, L. (2001). Analysing Europe’s borders. IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin [online], Recuperado de http://www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/publications [ Links ]

Paasi, A. (1991). Deconstructing regions: notes on the scales of spatial life. Environment and Planning, (23), 239-256. [ Links ]

Paasi, A. (1999). Boundaries as social practice and discourse: The Finnish-Russian border. Reg. Studies, (33), 669- 680. [ Links ]

Pestsov, S. (2015). Border and transborder regions. En Sevastianov, S., Laine, J. y Kireev, A. (Edit.), Introduction to Border Studies (pp. 139-154). Vladivostok: Far Eastern Federal University. [ Links ]

Planes, LL. y Biosca, M. (1978). El Petit llivre de Catalunya Nord. Perpinyà: Ed. de l’Eriçó. [ Links ]

Prat de la Riba, E. (1978). La nacionalitat catalana. Barcelona: Barcelona Edicions [ Links ]

Rubin, H. y Rubin, I. (2005). Qualitative Interviewing. The Art of Hearing Data. London/New York: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Sahlins, P. (1998). State formation and national identity in the Catalan borderlands during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. En Wilson, T. y Donnan, H. (Edit.), Border identities. Nation and state at international frontiers (pp. 31-36). Reino Unido: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sales, N. (2004). Tractà dels pirineus, el tractat dels pirineus. Estudis d’Història Agraria, (17), 829-842. [ Links ]

Vilar, P. (1962). La Catalogne dans l’Espagne moderne. Recherche sur les fondements économiques des structures nationales. Paris: Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes. [ Links ]

Wolfe, S. y Schimanski, J. (Edit.), (2007). Border Poetics De-limited. Hannover: Wehrhahn Verlag. [ Links ]

2In seeking a more accurate definition of the term, the Catalan geographer Joan-Francesc Castex-Ey asks: What is it essentially that identifies this cross-border Catalan region? An area of Catalanness astride a political border in the vicinity? A plural, multiple Catalanness, but which has common denominators and projects to share? A common language, Catalan, despite the striking dissimilarities […] on either side of the border? (2008, p. 3; translation from the author’s own Spanish translation of the original Catalan).

4Homi Bhabha (1994), in The Location of Culture, advocates the construction of this third space in which domination is overcome and more creative forms of cultural identity are produced based on interactions and interdependencies between nations, territories, races, genders, and social classes.

6TN: The comarca (Catalan plural comarques; Spanish plural comarcas) is a local administrative division in Spain, somewhat similar to the English word county.

9I have employed this designation as it is the most appropriate as a cultural definition of the region. The term is attributed to Llorenç Planes and Monserrat Biosca in a text published in 1978: El petit llivre de Catalunya Nord.

10The current surge of the independence movement in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, and the recent attempt to declare an independent Catalan Republic, are an example of this.

Received: April 04, 2018; Accepted: October 01, 2018

text in

text in