Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.26 n.51 México Jan./Jun. 2014

Artículos

Systemic Violence, Subjectivity of Risk, and Protective Sociality in the Context of a Border City: Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

Violencia sistémica, subjetividad del riesgo y socialidad de resguardo en el escenario de la ciudad fronteriza de Ciudad Juárez, México

Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez

Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez salvador.salazar@uacj.mx

Fecha de recepción: 23 de octubre de 2012.

Fecha de aceptación: 6 de julio de 2013.

Abstract

Using a sociocultural perspective to examine the context of systemic violence in the border city of Ciudad Juárez, this article analyzes a subjectivity of risk has been produced, based on an analysis of excerpts from interviews of social actors related to the fields of political, business, religious, and journalistic discursiveness.

Keywords: systemic violence, subjectivity of risk, protective sociality, border town, Ciudad Juarez.

Resumen

En el artículo se analiza, desde una perspectiva sociocultural y en relación con el contexto de violencia sistémica presente en la ciudad fronteriza de Ciudad Juárez, cómo se ha venido produciendo una subjetividad del riesgo a partir del análisis de diversos relatos de entrevistas aplicadas a actores sociales adscritos a los campos de discursividad político, empresarial, religioso y periodístico.

Palabras clave: violencia sistémica, subjetividad del riesgo, socialidad de resguardo, ciudad fronteriza, Ciudad Juárez.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this article is to analyze the way Ciudad Juárez, a border city in northern Mexico, has created a subjectivity of risk encouraged by the dominant presence of systemic violence, from a sociocultural perspective. using a methodological strategy, it focuses on narratives generated by various actors belonging to the fields of political, business, religious and journalistic discursiveness in an attempt to link the two concepts from the emergence of subjectivity or the return of the subject (Reguillo, 2000). In this respect, the border city is divided into densely complex sociocultural and communicational overlappings, creating new forms of coexistence, where, in the case of Ciudad Juárez, what is called protective sociality in this article prevails.

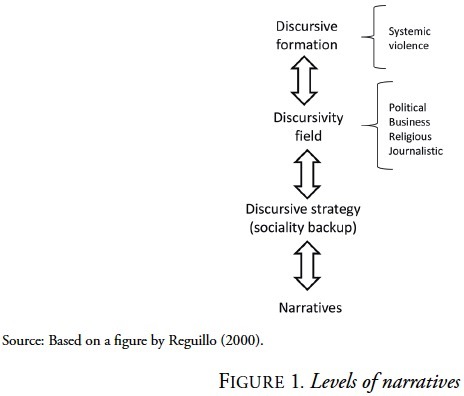

As discussed below, the analysis strategy (figure 1) is divided between discursive levels showing how the narratives generated by the various actors cannot be examined outside discursive fields (Laclau and Mouffe, 2004) or in relation to a context —the level of discursive formation (Foucault, 1997)— which refers to the presence of systemic violence in this border city scenario. The term "systemic violence" locates the presence of various forms of violence, the increase in homicides in recent years, most visibly through the phenomenon of feminicides,1 the transformation of the urban landscape and its heavily-guarded architecture that promotes impenetrable gated communities with their surveillance technology, the complacency of a labor policy that favors a cartography of marginality characteristic of the Maquiladora Industry,2 and the increasing presence of securitization policies (Salazar and Curiel, 2012) by the Mexican state—particularly the Mérida Initiative and various police-military operations such as the joint Chihuahua-Juárez operative.3

Although attention focuses on the analysis of narratives generated by various actors, it would be a mistake to restrict oneself to a decontextualized description that does not allow social issues to be identified as a dynamic process, in which the actors perform actions, produce discourses and construct meaning of the world, on the basis of negotiation processes in relation to spheres of belonging and always from a specific, historically constructed place.

The analysis of the production of a subjectivity of risk in the scenario of Ciudad Juárez, the reflective position that characterizes the social actor in relation to the sense of risk, cannot be understood outside the presence of a context dominated by violence, which, among other dynamics, has led to a growing cultural anxiety (Martín-Barbero, 2004), and the increasing precariousness of the bonds of affection and recognition.

Fieldwork was conducted through a series of semi-structured4 interviews with various social actors in Ciudad Juárez, belonging to the political, business, religious and media fields of discursiveness,5 on the basis of the assumption that these actors generate narratives in which risk is the dominant sense, always in relation to its attachment to discursive fields.

Analyzing narratives allows one to work at the narrative level that refers to the empirical realization of discourse, but also requires not confusing the production of subjectivity with individual aspects, or reducing it to a simple set of personal opinions that actors have in relation to the world. Stories are one of several resources used in the discursive strategy of social actors to negotiate, resist or appropriate their membership of a discursive field. This is done to avoid falling into a totalizing interpretation of the story, which is considered by him and from him to define the meaning and configuration of the discursive field. Any social process, and specifically for the case of this article, the one showing the production of a risk subjectivity involves unequal, unbalanced power relations, and one must strive to understand that although in the stories that will be analyzed, risk is the common denominator, within the discursive field itself, other subjective logics are configured that question or confront the dominance of risk.

The article is divided into three sections. The first focuses on the analysis of various accounts, derived from the semi-structured interviews with actors related to the fields of political, business, religious and journalistic discursiveness, with the aim of determining how a subjectivity of risk is produced in the current context of Ciudad Juárez. The second section aims to move to a denser level of interpretation, by linking the implications of the production of this risk subjectivity in the current context of systemic violence to the presence of a protective sociality that redefines the meaning of coexistence and interaction by the border town dweller. The article ends with a third section, designed to propose an alternative, given the dominance of this protective sociality that has been brewing in the production of risk subjectivity and the presence of systemic violence, by betting conceptually on the definition of a new logic of sociality in which, beyond the dominant presence of risk and protection, recognition promotes new forms of coexistence in the setting of this border city.

ESTABLISHED NARRATIVES: SUBJECTIVE RISK PRODUCTION

Risk has been cited as the dominant meaning in the grand rhetoric of securitization and protection, not only characterizing the scene of the northern border city of Mexico, but also, a context in which the ideals of a "triumphant globalization" have succumbed in the face of the evidence of exclusion and marginalization experienced by large majorities in the world.6 In a simple definition, risk refers to uncertainty or the contingency of upcoming damage, to being exposed to any danger that acquires greater presence and visibility from whatever bears the stigma of threat.7

Beyond the mere definition of the term, the risk is not inherent in our current context, and moreover, is not the exclusive concern of contemporary sociological reflection. In the 19th century, Durkheim used the concept of anomie to provide a conceptual resource to support the principle of functionality and order characteristic of the project for the first modernity. The modernization project, based on the principles of progress, found its socio-political enclave in the integration and functionality strategies of order, in which "anomie" constituted its means of achieving moral legitimacy in the face of the crisis implied by the premises of Enlightened thought. Mónica Guitián (2010) suggests an interesting path at the junction between Durkheim's anomie as a banner in the quest for balance and functionality in the modern project, and the risk that, from Beck onwards (1998), is anchored as a reference for the meaning of the current context. The scenario of systemic violence and its various expressions, ranging from the increasing number of homicides to the dismantling of the frameworks of certainty that characterized the presence of the project for the modern nation-state, have led to the fact that, "Risk is the perceptual and intellectual pattern that mobilizes a society faced with the construction of an open future filled with insecurities" (Beck, 2008:21).

For our analysis, risk subjectivity refers to the perceptive production of disenchantment and uncertainty, triggered by the presence of systemic violence, encouraging new logics of encounter in which risk is the dominant anchor of a new form of sociality in border cities. Risk and the overwhelming presence of violence, have positioned themselves as the horizons of interpretation of various actors resident in Ciudad Juárez. Based on the narrative-account, as the concrete level that will enable us to construct the analysis, the author of this paper works with excerpts from interviews in order to begin by analyzing the presence of risk as a dominant meaning, and discover behind this risk subjectivity the establishment of structures, rules and values within a legitimate order for the speaker, comprising what has been called protective sociality in this paper.

Safeguarding securitization (political and business fields)

The first line of analysis includes actors belonging to the business and political discursive fields. In another text, the author posited the importance of analyzing what he called the securitization project (Salazar and Curiel, 2012), in the current context of violence, characterized not only by the use of police-military strategies by the Mexican government,8 but also by the implementation of projects designed to promote the idea of police-military security and economic development9 as well as the resources for reducing the presence of violence and risk.

Our city and the whole country is drowning in an unprecedented wave of crime and drug abuse in young people... we wonder what happened? When did we lose our way? ... before everyone was raised in adversity... the government is making an effort... They have sent thousands of soldiers and police, but the problem is the organized crime gangs who threaten citizens... if it were not for the joint Chihuahua-Juárez Operation, we would be even worse off, with more murders and disappearances..." (Excerpt from interview with local state legislator).

This fragment reveals two interesting trajectories. On the one hand, "crime" and "drug addiction" are resources that attempt to legitimize the direct participation of military and police security institutions in surveillance work. The implementation of the joint Chihuahua-Juárez Operation was a key moment in the debate by the various actors embedded in the political and business spheres, who justified its application on the grounds that it would restore order and security in the city. The figure of "organized crime" appears in the fragment as the main promoter of the outbreak of violence, thereby seeking to justify the continued involvement of various military and police authorities in surveillance and detention.

The account also shows how a sense of temporality is promoted in which "before" refers to the youth-adult dichotomy, for example, "At what point did we lose our way?" or "Before everyone was raised in adversity," — becomes a source of legitimation of a temporality that marks the risk and uncertainty of young actors. Although the term "adversity" is related to the use of the term "before," making the sense of risk a continuous reference, the time difference between "before" and "now" is emphasized through the term "effort" in a present characterized by the disappearance of discipline and order. Risk is presented as the characterization of present time, in which morality codes and the "sense of law and order" of the past have been lost or reduced, in an attempt to promote the participation of public security agencies tasked with restoring certainty.

In regard to this meaning attributed to the axiological crisis, the following account shows how the narrative focuses on the disenchantment with the figure of "society."

here the problem is not the drug dealers; it is the passivity of society, which fails to acquire the awareness needed to raise its voice... if we do not protect the image of the city, if the government does not do its job of providing security, the little investment we have will disappear... young people involved in drug trafficking must be rescued; we must provide them with opportunities, they are our responsibility... (Excerpt from interview with businessman).

Although the modernizing project embarked on the task of exalting the figure of "society" as a reference to universality,10 in a context dominated by the maxim of free markets and private capitalization of the socio-political obligations of the state, the reference to figures such as "loss of investment" or "raising their voice" constitute the resources of a perspective that regards the risk of economic uncertainty as a problem for reproducing its dominant project. Once again, the figure of "youth" bears the burden of the stigmatization of the threat of the subjectivity of risk. As we saw from the first account, in this "young" actor, there is a constant reference to the loss that equates the distinction between the idealized "before" and the "present-future" as a threat.

However, at the beginning of this paper, it was stated that the aim is not to generalize on the basis of an excerpt from a description of a field of discourse such as politics or business, but simply to find, in the accounts provided, evidence that will enable one to determine how a subjectivity of risk is created from the supports and narrative figures that characterize these excerpts. The two accounts coincide in the implementation of securitization policies and determining the stigmatized figure of "youth" as a threat, but above all, they cite risk —of unstable security and the implementation of a free market-based economic project— as the prevailing sense.

Between Fears and Spells: "And Where Will you Spend Eternity?"11 (Religious Field)

The field of religious discourse is crucial to understanding the presence and dominance of uncertainty and disappointment in the current context of Ciudad Juárez. It comprises a multiplicity of strategies that limit beliefs or dogmas in relation to the sacred. Its inclusion in one of the discursive fields being analyzed shows how religious issues are re-emerging with significant presence during the various stages of life of the city's inhabitants. Although the modernization project embarked on the task of promoting a dynamic of desacralization, seeking to limit the presence that "sacred" issues had achieved in premodern religious institutions, their presence continues to be a key resource for understanding how disenchantment and uncertainty are established among the social actors in this border city.

Beyond the analysis regarding how the various religious affiliations (ranging from a Catholic majority, through the significant presence of various Christian churches and other denominations) present themselves,12 what is of interest here is the set of accounts making the sacred a source of legitimacy in response to the sense of risk. Recent years have seen an increase in strategies designed to promote figures related to the religious world, as reference of meaning for reducing the presence of risk. Billboards on the main avenues of the city, with messages related to terms such as "salvation," "repentance," "peace," "Christ," "evil," as well as the publication and distribution of brochures, bulletins and newspapers,13 have become highly profitable dissemination practices for various religious organizations and groups. They constitute dissemination practices, which, in the current context of violence, acquire the potential to penetrate various sectors at due to the assimilation of risk as a condition inherent in the experience of living in the city. The following excerpts from interviews are related to this issue.

The problem we have experienced in the past few years of violence in the city, has to do with the loss of the fear of God and universal values... The problem is that people, especially young people, are no longer afraid of God or sin... It is our duty to bring people back to the path of goodness and the love of God. (Excerpt from interview with Catholic priest).

Nowadays, with all this violence, we should reflect on what the Bible has to say to us: "What good is it to man if in the end he loses his soul?" ... yes, there is fear among the brothers, there is always the underlying fear you could be killed by a stray bullet on the way home or to the market or to the movies, but within that panic, there is confidence that God is present and that He looks after our path... (Excerpt from interview with Christian Pastor).

The increase in the number of homicides, particularly during the period from 2008 to 2011, fueled a rhetoric14 of the sacred embodied in the Christian maxim, "Repent and believe in eternal life." Expressions such as "God the Father," "the Word of God," "loss of soul," "loss of life" or "fear" are echoed in the everyday grammar of risk, and established as a legitimizing resource by a sphere of belonging encouraged by the presence of violence. The two accounts contain opposite meanings of the use of the term "fear." Whereas for one, it constitutes a resource for legitimizing the story, by seeking to emphasize the figure of "God" or "universal values," the second uses the term as the negation or overcoming of a human condition in the presence of the divine figure. In other words, the first excerpt uses the term "fear" to foster the presence of the person regarded as a promoter of certainty, whereas in the second case, it is linked to an expression of the worldliness that must be overcome in protecting divine issues.

The domain of uncertainty, a characteristic of the subjectivity of risk, is established through the presence of the term "death." Not only as a result of the increase of homicides, but also in the Christian moral maxim of a life beyond this earth, which will be obtained provided one wears the badge of "Christian belief," "something that everyone is afraid of is death, the possibility of dying on the street... but for the Christian believer, death is merely a moment prior to the next life, it is an intermediate stage we are waiting for" (Excerpt from interview with Christian Pastor).

One should not overlook the fact that the precepts of both the Catholic and the Christian tradition establish the figure of "salvation" with the aim of providing an interpretation of certainty in response to the underlying threat of losing one's life. Dying, which is a more everyday occurrence in violent contexts, encourages a rhetoric that relies on highly profitable practices of belonging for a population that assumes risk as an inherent condition in its everyday experience. The increase in religious events in public spaces (parks, plazas, shopping malls) organized by various churches, has been a constant in Ciudad Juárez. Strategies such as songs of praise, preaching, or the ritual of worship, have attempted to insert this sacred rhetoric into the city's inhabitants.

Like the analysis of the stories related to actors attached to political and business discursive fields, a temporal logic of the precarious nature of certainty is presented, between a current moment referring to a sense of "crisis" of axiological codes instituted in the field itself and a future time with the hope of restoring or inserting these codes into the quest to provide a space for sacred rhetoric.

Finally, the figure of "youth" and "children" are branded with the stigma of risk. Nevertheless, the reference marking the temporal meaning of the future with the ideal of "salvation" also identifies the present as an expression of the axiological crisis.

I think we are raising our children the wrong way... we have given them too much freedom and now we have a problem... what we must do is speak sternly and promote fear in respect... nowadays people have no respect for spiritual things. young people today are not afraid, and they should be afraid of Christ, and realize they are sinners (Excerpt from interview with member of Christian community, "New Wine")

Figures such as "fear," "respect for authority" or "stern words" are constant resources in a strategy that seeks to deposit the expression of disenchantment in youth. "Being afraid," and "Being a sinner," are figures that have found violence to be a highly profitable promotional landscape, since it is seen and defined as the expression of an axiological crisis that makes contingency an ideal setting for opposing the rhetoric of the sacred.

Narratives of Self-censorship (Journalistic Field)

The third stage of analysis comprises accounts by actors belonging to the discursive field of journalism. For the purposes of this article, this section focuses on journalists and their place in the strategy for creating newspaper articles, bearing in mind that this and the field of journalism in general, are part of denser, more complex field: the media. To analyze the production of risk subjectivity expressed by journalists, and its implications in the configuration of a protective sociality, this section focuses on the wake-up call by Martín-Barbero that, "If television attracts, it is because the street expels" (Martín-Barbero, 2004:77). Within the current context of systemic violence and the dominant presence of risk, journalists have found a highly profitable scenario for legitimizing their position as a means of visibility for a readership that seeks guarantees of certainty to offset a medium that narrativizes violent events.

In the context of systemic violence, journalists have discovered that the recurrent practice of anecdotizing15 the violent event constitutes a strategy for promoting their action mainly by journalistic self-censorship as a means of allowing its activity against a backdrop of risk: "The problem is that our city attracts danger... which is why self-censorship or not speaking is sometimes better, to avoid being threatened" (Excerpt from interview with journalist 2). In a scenario in which the number of homicides eventually totaled ten to twelve a day, the strategy for publicizing the event was assumed as a "responsibility" to inform the public that found in the press and news programs a kind of protective map since they publicized places, roads, shopping centers and meeting spaces close to the event. "We know that our job is to report on what is happening in the city... now violence is present and we are obliged to report on various violent events... the problem is that we have lost colleagues who have been killed for reporting on homicides, and our activity is threatened by what we report or silence" (Excerpt from interview with journalist Fragment 1).

This perception of risk is not only due to the number of journalists killed in the past four years, but also to the constant threat from various actors whose interests are affected by the information journalists possess. Journalism is vulnerable, not only because of the latent threat implied by the presence of violence and the loss of life, but also because of the conditions of those who control the editorial process of news items. Uncertainty and risk are powerful determinants of silence and censorship in an environment in which the presence of a news item can threaten the profitability of a particular form of media.16

In this respect, the number of journalists killed, not only in Ciudad Juárez, but in the rest of the country, and the self-censorship that limits the position of journalists, has elicited recognition from several journalists who have promoted organizations and processes to protect their practice.17

These three landscapes of the narrativization of experience visible in the accounts of actors belonging to various fields of discourse reveal trajectories showing the increasing penetration of the perception of disenchantment and uncertainty characterizing the presence of the subjectivity of risk. The prevalence of securitization projects, the capitalization of religious rhetoric with its reference to a crisis of principles and judgments instituted by various churches, and the practice anecdotizing journalistic practice shows how risk has penetrated the real world scenarios of various actors belonging to fields of political, business, religious and journalistic discursiveness.

Linking these accounts in the production of a subjectivity of risk, and their relationship with the presence of systemic violence requires moving to a level of structural analysis within the enclave of its reproduction, termed "protective sociality" in this article. In other words, a new way of "being together," dominated by uncertainty and disillusionment fostered by the contingent penetration of an underlying threat.

CONFIGURING A PROTECTIVE SOCIALITY

The securitization project promoted by various actors, the exaltation of fear and spells through the increasing presence of religious phenomena, and the vulnerability of the self-censorship that reveals the limits of what can be said in the prevailing context of systemic violence, takes one to a higher level of analysis: how risk subjectivity has been penetrating various actors within the scenario of Ciudad juárez. However, although the previous section attempted to use the various narratives to show how this risk subjectivity is configured, based on the fact that any narrative forms part of discursive strategies designed to locate, negotiate, and promote belonging within discursive fields, one should realize that they materialize in beliefs expressed by practices by various actors, with the aim of legitimizing their position in regard to these fields. In other words, accounts are not merely individual expressions designed to make meanings of risk visible but in their coordination and link with other practices, they create strategies, instituting them as rituals of legitimization anchored in discursive fields which, as recurrent practices, favor the configuration of protective sociality.

Let us move to the following level containing Discursive Training, the contextual, historical delimitation of what can and cannot be said in relation to the dominant presence of systemic violence, with the fields of discursiveness and their discursive strategies expressed in the narrative accounts analyzed. Below is an analytical matrix of the production of this risk subjectivity and the creation of a protective sociality, on the basis of three trajectories: reality as a symbolic order, the dynamism of the production of meaning and the reproduction of power favored by the process of ideological questioning.18

Reality as a Symbolic Order

What people call reality refers to "a symbolic order constituted by and constituting every historical moment in every society; that which is experienced as reality and displays collective forms of assuming, shifting or denying." (Murillo, 2008:25). In this respect, the Lacanian premise of reality as a symbolic order is based on what is experienced by the various subjects as "real." What we assume as reality is always already symbolized, and forms part of a structuring logic of the symbolic order in relation to a context of meaning. The accounts comprising the production of a subjectivity of risk do not form part of an individualized fantasy nor are they the result of an external "manipulative" machinery. Instead they are anchored in the configuration of an unfinished symbolic order that delimits the meaning of the expressible by actors based on belonging to a dominant discursive field (Foucault, 1992). Figures highlighting the meaning of uncertainty or disappointment in the accounts such as "drugs," "military men," "threat," "fear," "loss of security" and "passive society" are references to anchors from which people do not merely speak of external individuality but the configuration of an order of meaning that attempts, using these resources and other strategies to promote the systems of visibility and enunciability characteristic of a protective sociality.

The dynamism of the production of meaning

The second area relates to the dynamism of the subjective production of risk. In this respect, the various anchors of meaning observed through the continuous presence of the figures analyzed in the accounts do not seek to define the discursive level as merely a "linguistic relationship," but rather as a network of enunciation that circulates and connects discourse levels.

The various stories constitute anchors of meaning, from which representations of risk are positioned, which, beyond essentializing and naturalizing terms, produce the control that certain signifiers acquire in relation to subjects' belonging to discursive fields. In other words, the question one must ask is not limited to seeing whether the terms "drugs," "military men" and "organized crime," present throughout the various accounts, are relevant as references of meaning for a subjectivity of risk. Instead, one should explore how they are linked in narratives that shift between the various actors, making not only belonging visible but also resistance and invention in relation to a protective sociality. In this respect, although the selection of accounts was intended to emphasize the sense of vulnerability, uncertainty and disappointment characterizing the production of a subjectivity of risk, one should bear in mind other subjective logics that have been positioned in the search to reduce the presence of risk and its relationship to the context of violence.

In other words, this subjectivity of risk has been accompanied, within these and other fields of discourse, by a dissident subjectivity which finds in the formation of a new activism resistance strategies for coping with the use of uncertainty by the actors who promote risk. As we mentioned, every field of discourse is not only an enclosed space of reproduction but a web of struggle and negotiation, a domain that on the one hand, favors the reproduction of risk and also the generation of other dissident subjectivities.19

The domain of the symbolic order and the presence of questioning

The third axis of analysis is based on the principle that any discursive strategy constitutes a dynamic conditioned by power relations interwoven with the fields of discourse. As mentioned at the beginning of the text, it is assumed that these four fields of discourse (political, business, religious and journalistic), are presented as dominant spaces of belonging thanks to the relationship that has arisen between the subjectivity of risk and a context of systemic violence. If the production of meaning that becomes visible in the accounts-narratives is not a passive expression, a simple individual expression and instead is designed to provide interpretations of domain, due to their characteristics of penetrating the creation of a risk subjectivity, the four fields of discourse seek to use the presence of violence to promote a subjectivity that will enable them to cite risk not only as a condition of contingency or damage but above all as a means of presence and legitimacy given the vulnerability assumed in risk production. Assuming that all subjective logic is part of a network of discursive articulation that goes beyond its individual configuration, questioning, in the Althusserian sense, is developed as one of the mechanisms which, from the fields of discourse and their institutionalization strategies, lead one to place the focus of attention on the penetration these fields promote to encourage positions of domination. Although this paper focuses on the analysis of various accounts, the production of a risk subjectivity is also coordinated by practices that shape rituals of enunciation. The mass meetings in various public places held by religious organizations, through intervention or development projects in the city, such as We are all Juárez," — encourage a protective sociality favored by the dominant presence of the subjectivity of risk.

In a context of systemic violence, reflected in the number of homicides in the promotion of a market supply characterized by exclusion as exemplified by the maquiladora industry, and the increased presence of securitization projects based on police-military strategies the creation of a protective sociality shows how the link between discursive levels shifts from the production of risk subjectivities, through its close relationship to strategies connecting the subjective to institutionalized backup processes characteristic backup of this new sociality.

CONCLUSION. THE CROSSROADS OF THE POSSIBLE

Without falling into a kind of ominous prospect of the uncertain domain of inevitability, there is an urgent need to encourage critical pessimistic thinking (Reguillo, 2000), an initial demanding condition for managing to locate and penetrate the cultural frameworks of our contemporary societies. The various stories discussed here, their link with the production of risk subjectivity, lead to a current situation in the border city, in which the attachment of various players to dominant discursive fields has permitted a strategy for dramatizing uncertainty and disappointment.

Given the increasing penetration of violence, the resurgence of backup practices and their various logics for capitalizing risk, the question that arises is to how to encourage a form of sociality based not on protection and vulnerability, but rather on the recognition and certainty that mitigate the sense of risk. In the quest to reduce the dominant position acquired by risk, the call to establish routes of recognition in which reflexivity constitutes a key resource is a demand that academic spaces are obliged to promote. A recognition which, unlike those put forward in fields such as religious discourse, which have used the crisis of meaning to encourage attachment strategies to legitimize their rhetoric on sacred issues, emerges and is based on strategies that find in the critical reflectivity of actors, interpretations to offset those that have taken advantage of the production of risk. Thinking about the elimination of risk or the fears present in the various imaginaries that cut through our everyday contexts is impossible, but what is necessary is to lower their impact and promotion of uncertainty and disappointment that dominate the scenario of Ciudad Juárez. There is also a need to transform perception through discursive strategies that address the subjectivity of risk, and establish new routes of recognition to resignify the prevailing symbolic order, in order to overcome a scenario dominated by the colonization of risk by interpreting maps of certainty. Given this presence of the subjectivity of risk and their dramatization of uncertainty, one should reconsider the reference by Richard Sennett (1997) in order to recall that politics began in the Greek city, in a scenario of the dramatization of recognition. The search for a new sociality, together with the dramatization of political aspects on the basis of performativities that overcome the instituted formality of backup should emphasize new strategies of recognition within the scenario of this northern border city of Mexico.

REFERENCES

Arfuch, Leonor, 2002, El espacio biográfico. Dilemas de la subjetividad contemporánea, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Beck, Ulrich, 1998, La sociedad del riesgo. Hacia una nueva modernidad, Barcelona, Paidós. [ Links ]

Beck, Ulrich, 2008, La sociedadedel riesgo mundial. En busca de la seguridad perdida, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Paidós. [ Links ]

Cervera Gómez, Luis Ernesto and Julia Estela Monárrez Fragoso, 2010, Sistema de Información Geográfica de la Violencia en el municipio de Juárez, Chihuahua: Geo-referenciación y su comportamiento espacial en el contexto rural y urbano (Sigvida), México, El Coleff/Conavim. [ Links ]

Eternidad, n.d., "Testimonios" section, Tu Eternidad, in <http://www.tu-eternidad.com/testimonios.html>, last accessed March 5, 2012. [ Links ]

Foucault, Michel, 1992, El orden del discurso, Buenos Aires, Tusquets. [ Links ]

Foucault, Michel, 1997, Arqueología del saber, México, Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Goffman, Erving, 2001, Estigma. La identidad deteriorada, Spain, Amorrortu. [ Links ]

Guitián Galán, Mónica, 2010, Las semánticas del riesgo en la sociedad moderna, México, UNAM. [ Links ]

Juárez Competitiva, n.d., Information section in Juárez Competitiva, in <http://www.facebook.com/juarezcompetitiva/info>, last accessed May 24, 2012. [ Links ]

Laclau, Ernesto and Chantal Mouffe, 2004, Hegemonía y estrategia socialista. Hacia una radicalización de la democracia, Buenos Aires, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Martín-Barbero, Jesús, 2004, "Mediaciones urbanas y nuevos escenarios de comunicación", in Patricio Navia and Marc Zimmerman, coords., Las ciudades latinoamericanas en el nuevo (des) orden mundial, México, Siglo XXI Editores, pp. 73-84. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch, 2011, Ni seguridad ni derechos. Ejecuciones, desapariciones y torturas en la "guerra contra el narcotráfico" de México, November 2011 Report, USA, Human Rigths Watch, available at <http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/mexico1111spwebwcover.pdf>, last accessed on November 25, 2011. [ Links ]

Murillo, Susana, 2008, Colonizar el dolor. La interpelación ideológica del Banco Mundial en América Latina. El caso argentino desde Blumberg a Cromañón, Argentina, CLACSO. [ Links ]

Pratt, Mary Louise, 2007, "Globalización, desmodernización y el retorno de los monstruos", Revista de História, Brazil, Universidad de Sao Paulo, No. 156, June, pp. 13-29, available at <http://www.revistasusp.sibi.usp.br/pdf/rh/n156/a02n156.pdf>, last accessed on September 10, 2012. [ Links ]

Reguillo, Rossana, 2000, "Anclajes y mediaciones del sentido. Lo subjetivo y el orden del discurso: un debate cualitativo", Revista Universidad de Guadalajara, dossier No. 17, Winter 1999-2000, available at <http://www.cge.udg.mx/revistaudg/rug17/4anclajes.html>, last accessed on November 11, 2011. [ Links ]

Salazar Gutiérrez, Salvador, 2012, "Periodismo y violencia: la producción de subjetividad del riesgo en el norte de México", Global Media Journal, México, Vol. 9, No. 17, pp. 63-80. [ Links ]

Salazar Gutiérrez, Salvador and Martha Mónica CURIEL GARCÍA, 2012, Ciudad Abatida. Antropología de la(s) fatalidad(es), México, UACJ. [ Links ]

Sánchez, Sergio and Patricia Ravelo, 2010, "Cultura obrera en las maquiladoras de Ciudad Juárez en tiempos catastróficos", El Cotidiano, México, UAM Azcapotzalco, No. 164, November-December, pp. 19-25. [ Links ]

Sennett, Richard, 1997, Carne y piedra. El cuerpo y la ciudad en la civilización occidental, Madrid, Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Zizek, Slavoj, 2003, El sublime objeto de la ideología, Argentina, Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Interviews

Local state legislator, (March, 2012), by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Businessman, (March, 2012) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Catholic priest, (January, 2012) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Christian Pastor, (February, 2012) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Member of Christian community, (February, 2012) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

First journalist, (November, 2011) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Second journalist, (November, 2011) by Salvador Salazar Gutiérrez, "La construcción simbólica de la relación vida-muerte en colectivos juveniles urbanos, en el contexto actual de la ciudad fronteriza del norte de México", Ciudad Juárez, México, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

1 The report "Sistema de información geográfica de la violencia en el municipio de Juárez, Chihuahua: geo-referenciación y su comportamiento espacial en el contexto urbano y rural", a study conducted by researchers at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Luis E. Cervera and Julia E. Monarrez Fragoso (2010), supported by Conavim (Comisión Nacional para Prevenir y Erradicar la Violencia contra las Mujeres), undertakes a comparative analysis of the number of homicides in Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez during the period from 2006 to 2008. In the case of feminicides —a term used to refer to the murder of a woman for gender reasons— it shows their increase, since between 2006 and 2007, 19 were registered in each state whereas by 2008 the figure was 111.

2 Sergio Sánchez and Patricia Ravelo (2010) in their article "Cultura obrera en Ciudad Juárez en tiempos catastróficos" show how, in the context of globalization and the free market, the maquiladora industry has established itself as the dominant transnational production strategy, outside Mexican state regulation concerning the Federal Labor Law. The maquiladora industry is characterized by labor flexibility, in which the dismissal of working men and women is common. They show how between 2008 and 2010, over 120 000 jobs were lost in the city, largely because this practice of dismissal was linked to the global economic crisis and the scenario of insecurity and violence that has prevailed in recent years.

3 In 2011, the international human rights organization Human Rights Watch published a report entitled, "Ni seguridad ni derechos. Ejecuciones, desapariciones y tortura en la guerra contra el narcotráfico en México", in which it analyzes various cities, including Ciudad Juárez, and refers to hundreds of complaints of torture against security institutions such as the army and various police forces.

4 Both the semi-structured interview and the in-depth interviews begin by providing an interpretation of society through the reconstruction of language, in order to analyze the narrative production created in the fields of discourse, specifically in the narratives produced by key actors that form part of these fields (Reguillo, 2000).

5 The document is the result of a research project entitled, "Socialidad del resguardo: la producción simbólica del riesgo en el contexto transfronterizo", held from january 2011 to September 2012, designed to analyze how the subjectivity of risk is produced in various social actors belonging to these four fields of discourse and in relation to the context of violence in Ciudad Juárez. The methodological strategy focused on actors belonging to these four fields: an entrepreneur, a receiver, two priests, an Evangelical Church pastor, and two journalists. General criteria for the selection included: a) belonging to an organization or group attached to one of the fields, b) having a type of membership which encouraged links with the transborder scenario: Ciudad Juárez-El Paso, Texas, and c) being considered socially relevant in decision-making related to the presence of violence.

6 It was decided to establish a distance from those perspectives that continue to promote the idea of a "city network" or "global city" that will be assisted by the efficient promotion of various dominant factors in the current context (the development of major information technologies, the free market of flows and goods and market deregulation, reduced state presence, etcetera), because as Mary Louise Pratt has said (2007), the term "globalization" and its various characterizations is devoid of a theoretical basis and has only served to attempt to legitimize political-economic projects that have favored the consolidation of predatory capitalism.

7 As Erving Goffman (2001) says in his text entitled Estigma. La identidad deteriorada, refers to the recurrent practice of a group to mark an individual with the aim of discrediting him.

8 The beginning of the article states that at the structural level, the securitization policies promoted by the Mexican government are mainly present as a result of two strategies: an international one, namely the Merida Initiative, and a second, more local or regional one, which has been the implementation of the joint Operations involving members of both military and police public safety groups. For a detailed analysis of this securitization project, see the text, Ciudad Abatida. Antropología de la(s) fatalidad(es), by Salvador Salazar and Martha M. Curiel (2012).

9 Several projects were carried out by businessmen and politicians from the three levels of government, with the intention of "promoting" the city to the national and international market. This was exemplified by the program "JuárezCompetitiva", supported and financed by local businesses, characterized by the promotion of concerts and consultation forums with the shared aim of, "Changing the image of the city, winning respect, showing the good side of the city, its products, its good people..." (Juárez Competitiva, n.d.).

10 Although it is not the aim of this article to analyze how the modern project was configured, the reference to Rousseau's social contract was a key element of a project that fostered a sense of universality and equality in a pact in which each individual makes his person and powers available to a general will emanating from a moral and collective body created by the association of all persons.

11 The phrase belongs to a billboard in one of the busiest avenues, and presents an image at two levels: one at the top showing various young people, accompanied by children dressed in white, with arms extended horizontally, on a background with a city lit by rays emerging from the center, and on the lower level, against a black background with distorted images of individuals as if they were "zombies" expelling fire from their limbs. The billboard contains the question, "Where will you spend eternity?" at the bottom, accompanied by a reference to a website (Eternidad, n.d.).

12 Although most people belong to the Catholic Church, recent years have seen a significant increase in Christian churches (Pentecostals, Baptists, Presbyterians), and other groups such as jehovah's Witnesses. There is also a large Mormon community in the region, and in the past two decades, the presence of Christian communities, not attached to any formal institution, has been a constant (one example of this is the "New Wine," community, regarded as one of the most important ones, with the greatest presence).

13 One of the most important newspapers published weekly by the Diocese of Ciudad Juárez. The weekly newspaper "Presencia. Palabra y presencia de la Iglesia Católica en Ciudad Juárez" has been one of the most important strategies in the city implemented by the Catholic Church, based on testimonials by various members (priests, religious or lay persons) in promoting institutional principles and events, but especially in the wake of the eruption of violence, there have been several speeches by priests linking events to biblical resources.

14 The classic definition of the term, referring to the art of persuasion, was used.

15 Anecdotizing means the practice which has dominated much of journalism in Ciudad Juárez, whereby the event is decontextualized, with the focus being placed on the specific conditions of the event. The description of what happened was reduced to the reference to the lifeless body and the arrival of the police forces or the army to preserve the scene of the crime. A number of journalists and reporters interviewed agreed that further investigation that would expand the information on what had happened was not possible due to the number of violent events recorded, but above all to the threat involved in gaining access to information that would highlight the link between the victims and the authorities and organized crime or drug trafficking groups.

16 In a panel discussion entitled "Rights and obligations of journalism," held in October 2012, several reporters stated that they constantly face censorship by members of their profession, from the person in charge of the editorial, to the owners of the newspaper or television channel whose interests are affected.

17 During the past two years in the cities of Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez, there has been an interesting debate among groups of journalists (both local and national), requiring the development of security protocols for journalistic practice in contexts of violence and militarization. While some efforts have been made in this regard, such as the series of meetings between groups of journalists, Chihuahua state government officials and Human Rights organizations, this has not been formalized, meaning that the vast majority of journalists and reporters live in a constant state of vulnerability.

18 While it is not the purpose of the text to expand the debate on the concept of ideology, for the purposes of this paper, the discussion by Slavoj Zizek (2003) in his essay The Sublime Object of Ideology, is taken up. From recovering Althusser with an interesting twist from the psychoanalysis of Lacan, it is argued that the problem of those interpretations that began to separate ideology as an axis of analysis from social issues was the limited perspective of citing it as, "False consciousness," without taking into account the dynamism and direction of the process revealed through the cynical logic of certain groups to promote a sense of domination.

19 Further analysis is required to deal with this dissident subjectivity that has recently occurred in the scenario of Ciudad Juárez. Various groups of artists, human rights groups, and civil society in general have promoted practices of resistance on the basis of activism observed through the implementation of strategies such as generating groups against violence. Foremost among them is the group "Our daughters back home," young women's art groups such as "Female Battalions" or "dwellings."