Introduction

The Mesoamerican Reef System (SAM) is the second largest barrier reef in the world, extending from the extreme north of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico, southwards through the waters of Belize, Guatemala, and northern Honduras (Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2014). The Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel (PNAC), as a part of this, is located on the Cozumel Island, which is considered the reef system with the greatest biodiversity in the Greater Caribbean (Ardisson et al., 2011; DOF, 2015; Dutra et al., 2021). The importance of this area is multiple: from being one of the main reef formations in Mexico, having a great variety of flora and fauna and being the base of the island's tourism industry (Ardisson et al., 2011; DOF, 2015; Dutra et al., 2021).

Coral reefs are predominantly cemented by corals and coralline algae and are considered among the most productive and biologically diverse ecosystems in the world (Sheppard et al., 2009; Davin and Brannet, 2010), as they provide habitat for a wide range of marine species, among which macroalgae stand out for their abundance and commercial value (DOF, 2015; Núñez Resendiz et al., 2019; Pereira Cuni et al., 2023). In addition, the reefs are characterized by having a high rate of primary productivity, providing protection to the coast against waves and storms, and generating substantial income for the local community through tourism, which is why they are considered ecologically and economically very important ecosystems (Puyana, 2017; Secaira et al., 2017; Spalding et al., 2017; Zucconi et al., 2018; Hutchings et al., 2019).

Macroalgae are a fundamental component of the reef flora, since they are not only the main primary producers, but also because they influence the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide, and contribute macro and micronutrients to the surrounding environment (Se-Kwon, 2012). For this reason, phycofloristic knowledge not only favors the realization of regional inventories, but also allows, in the long term, to establish any trend or change that indicates a threat to coral communities, as well as its use in monitoring and conservation works (Pellizzari et al., 2014; González and Torruco, 2015; Núñez Resendiz et al., 2019).

On the Cozumel Island, important investigations have been carried out focused on the knowledge of the phycofloristic diversity of the area (Reyes-Bonilla, 2011; Valadez et al., 2014; Acosta-Calderón et al., 2016; Loreto Viruel et al., 2017). Particularly noteworthy are the studies by Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González (1991), who record the reproductive status, tidal level, and distribution of the island's benthic marine algae in the intertidal zone, as well as those by Mendoza-González et al. (2000) and Mateo-Cid et al. (2006), in which the phycofloristic diversity of the subtidal zones of the PNAC is concentrated. The results of this research, in turn, were integrated together with records of marine algae from Cozumel, from 1958 to 2006, in the work of Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González (2007). However, despite the importance of these contributions to the knowledge of the diversity of the PNAC, no phycofloristic studies have been carried out that include morphological descriptions. Consequently, in some cases it is not possible to contrast new information with these works, generating underestimation or overestimation of the species richness (Núñez Resendiz et al., 2019; García-García et al., 2020, 2021).

In general, there are few phycofloristic contributions in Mexico that report the types of substrates to which each species presents proliferation affinities (Garduño-Solórzano et al., 2005; Sánchez-Molina et al., 2007; Patiño-Espinosa et al., 2022). However, this is a relevant aspect for the characterization of reef zones that are constituted of species with preferences for certain types of substrates that determine their presence, absence, or abundance (Hernández et al., 2021). This lack of updated information about reef environments, which are areas of ecological and economic importance for Cozumel, compromises the integrity of the resources that integrate them. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the taxonomic composition of marine macroalgae present in the PNAC and their affinity for the substrate, including a brief morphological description of each species and photographic references.

Materials and Methods

Study area

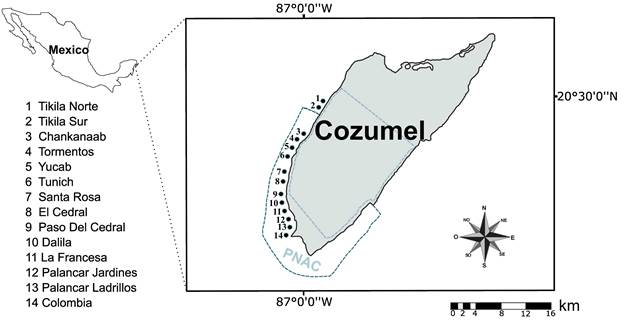

Cozumel Island is located in the Caribbean Sea, 20 km east from the Yucatán Peninsula (Álvarez-Filip et al., 2009). The PNAC is located on this island, extending from the northern end of the Paraíso reef (20°35'22''N, 86°43'46''W) to the southern end of the island, then continuing north to Punta Chiqueros on the eastern side (20°16'11''N, 86°59'26''W) (Álvarez-Filip et al., 2009). This area has an Am (f) type climate, warm humid with abundant rains in summer (Orellana et al., 2007), and is characterized by two well-defined climatic seasons: rainy from May to January, and dry in February, March and April (Climate-Data, 2019).

The PNAC is formed by an almost continuous reef development of approximately 24 reefs (Underwater Editions, 2003; Loreto Viruel et al., 2017), of which 12 were studied here: Chankanaab (CK), Tormentos (TM), Yucab (YC), Tunich (TH), Santa Rosa (SR), El Cedral (EC), Paso del Cedral (PDC), Dalila (DL), La Francesa (LF), Palancar Jardines (PJ), Palancar Ladrillos (PL), and Colombia (CB) (Fig. 1; Table 1). These reefs appear as carbonate rock structures of both low relief and high columns and buttresses that emerge through the sand, rising several meters above the bottom (Mendoza-González et al., 2000). Among the rock formations there are large carbonate sandy slopes; in addition, at the edge of the cliff, usually at depths of up to 30 m, there may be an abrupt drop with an almost vertical rock wall that, together with the rock formations and the sandy slopes, provides substrate for the establishment of different algae (Mendoza-González et al., 2000).

Figure 1: Map of collection locations on the island of Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Black dots indicate the location of the sampling sites. The numbers correspond to the names of the sites.

Table 1: Reefs where macroalgae were collected in the Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel, Cozumel Island, Quintana Roo, Mexico, including coordinates and collection months.

| Reef | Coordinates | Collection month | |

|---|---|---|---|

| October | November | ||

| Tikila Norte (TN) | 20°29'02''N, 86°58'17''W | x | x |

| Tikila Sur (TS) | 20°28'54''N, 86°58'23''W | x | x |

| Chankanaab (CK) | 20°26'28''N, 87°00'07''W | x | x |

| Tormentos (TM) | 20°25'38''N, 87°00'55''W | x | x |

| Yucab (YC) | 20°25'22''N, 87°01'20''W | x | x |

| Tunich (TH) | 20°24'28''N, 87°01'20''W | x | x |

| Santa Rosa (SR) | 20°22'42''N, 87°01'48''W | x | x |

| El Cedral (EC) | 20°22'09''N, 87°01'44''W | x | x |

| Paso del Cedral (PDC) | 20°21'55''N, 87°01'47''W | x | |

| La Francesa (LF) | 20°21'24''N, 87°01'43''W | x | x |

| Dalila (DL) | 20°21'26''N, 87°01'40''W | x | x |

| Palancar Jardines (PJ) | 20°19'30''N, 87°01'38''W | x | x |

| Palancar Ladrillos (PL) | 20°19'23''N, 87°01'38''W | x | x |

| Colombia (CB) | 20°18'56''N, 87°01'35''W | x | x |

These reef formations have unique characteristics in the region, and they have positioned the island, due their ecological and economic importance, as one of the main international diving destinations (Santander, 2009; DOF, 2015). Two additional localities were included in our study: Tikila Norte (TN) and Tikila Sur (TS), which, although they are not part of the PNAC, constitute the surrounding region (Fig. 1), being areas of coral repopulation and locality in Cozumel where it is intended to build the Fourth Cruise Dock (DOF, 2022) for vessels that have a capacity of approximately 2500-7500 passengers, such as those that currently arrive and that dock at the Punta Langosta, Puerta Maya, and International docks. According to the APIQROO (2023), to date, Cozumel has the first place in the arrival of cruise ships in Mexico. Therefore, the results obtained from these localities are presented and discussed together with the PNAC.

Field work

The collections were made during October and November 2018, previously recorded as a highly diverse season (Mendoza-González et al., 2000; Mateo-Cid et al., 2006), by autonomous diving (SCUBA). The immersions were carried out at depths from 7 to 30 m. Phycological material (up to 1 cm) was collected by detaching it from the substrate manually or with the help of a spatula and placed in resealable bags (Ziploc®). Only most evident species were collected, including epiphytic ones.

Photographs and videos were taken in situ with a camera Garmin VirbXE (Kansas, USA). The samples were placed in plastic trays; photographs of the wet specimens were taken, they were mounted on herbarium sheets and later integrated into the marine macroalgae collection of the herbarium UAMIZ (Appendix) of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City (acronym according to Thiers, 2023). All samples for each species were designated with a field number (e. g. TH14, SR19, DL13, PJ16) and are part of a same voucher (October or November, as appropiate, each one with its field numbers associated), or an herbarium sheet, under a voucher number (e. g. TH14, SR19, DL13, PJ16 are part of a same voucher UAMIZ-1474 for October).

Cabinet work

For the morpho-anatomical characterization, a stereoscopic microscope Leica ZOOM 2000 (Heidelberg, Germany) and an optical microscope Leica DMLB (Heidelberg, Germany) were used. Cross and longitudinal sections were made by hand using a double-edged razor. In the case of calcareous algae, the calcium was removed with acidified solution 1N HCl. Photomicrographs were taken using a Quasar USB 2MP (Bophal, India) digital camera adapted to a microscope Leica DMLB (Heidelberg, Germany). The photographs of the habits were taken with a Nikon D7000 (Tokio, Japan) digital camera.

The taxonomic determination was made with specialized literature (Schneider and Searles, 1991; Richardson and Ginger, 1994; Littler and Littler, 2000; Collado-Vides et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2012; Mendoza-González et al., 2014; Camacho et al., 2015; Acosta-Calderón et al., 2016; 2018; Godínez-Ortega et al., 2019). The phycofloristic list was presented according to the classification used by Wynne (2022) and the current taxonomic status of each species was reviewed in the Algaebase database (Guiry and Guiry, 2023). The substrates where the macroalgae occurred were classified according to the proposal of León-Álvarez et al. (2007), remaining as follows: epilithic (rocks), psammophytic (sand), epizoic (particularly Porifera and Cnidaria (Anthozoa)) and epiphytic (algae).

Results

A total of 42 species of macroalgae were identified, which are shown in the Appendix, accompanied by the type of substrate in which they grew and the date of collection. Of the total taxa, 5 corresponded to Ochrophyta (12%), 12 Rhodophyta (30%) and 25 Chlorophyta (58%), distributed in 9 orders, 16 families and 26 genera (Appendix). The best represented families were Dictyotaceae for Ochrophyta (three species), Ceramiaceae and Rhodomelaceae for Rhodophyta (three species each) and Halimedaceae for Chlorophyta (18 species). Of the two months analyzed, November had the highest number of species: 42 taxa.

Of the total number of macroalgae species, 18 new records for the PNAC (indicated with *) were obtained: Dictyota guineënsis (Kützing) P. Crouan & H. Crouan, Dictyota pinnatifida Kützing, Lobophora guadeloupensis N.E. Schultz, F. Rousseau & L.Le Gall, Sargassum cf. cymosum C. Agardh, Sporochnus pedunculatus (Hudson) C. Agardh, Ptilothamnion speluncarum (Collins & Hervey) D.L. Ballantine & M.J. Wynne, Dasya antillarum (M. Howe) A.J.K. Millar, Ulva intestinalis Linnaeus, Cladophora liniformis Kützing, Rhizoclonium riparium (Roth) Harvey, Caulerpa cupressoides var. flabellata Børgesen, Avrainvillea asarifolia Børgesen, Halimeda scabra M. Howe, Rhipocephalus phoenix (J. Ellis & Solander) Kützing, Udotea cyathiformis f. infundibulum (J. Agardh) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, Udotea cyathiformis f. sublittoralis (W.R. Taylor) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, Udotea luna D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler and Udotea cf. unistratea D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler. With the exception of Sargassum cf. cymosum, Sporochnus pedunculatus, Dasya antillarum, Ptilothamnion speluncarum, Ulva intestinalis, Cladophora liniformis, Caulerpa cupressoides var. flabellata, Udotea cyathiformis f. infundibulum, Udotea cyathiformis f. sublittoralis, Udotea luna and Udotea cf. unistratea, which constitute new records for the island, and Lobophora guadeloupensis, which in turn constitutes a first record for Mexico (indicated with **), the rest of the species had already been reported for the island, although not for the PNAC.

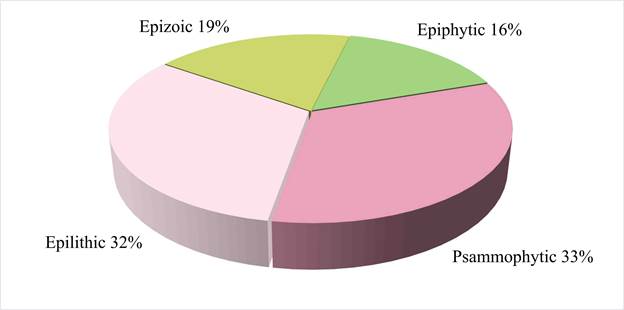

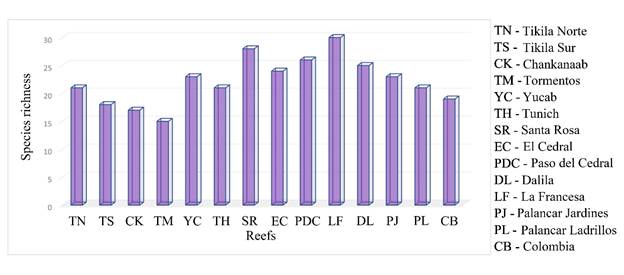

Regarding the type of substrate in which macroalgae develop in our study area, it was observed that 25 species establish themselves in more than one type of substrate, of which one was brown, six were red and 18 green algae. Among these are Dictyota pinnatifida, Dasya pedicellata (C. Agardh) C. Agardh, Halimeda opuntia (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux, Penicillus dumetosus (J.V. Lamouroux) Blainville and Rhipocephalus phoenix, species that grow on rocks, sand and invertebrates. Of the rest, 18 species develop on a single substrate, two on rocks (one brown, one green), six on sand (two brown, four green); and 12 are epiphytes, of which eight records were red (Amphiroa fragilissima (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux, Jania adhaerens J.V. Lamouroux, Hypnea spinella (C. Agardh) Kützing, Centroceras clavulatum (C. Agardh) Montagne, Ceramium luetzelburgii O.C. Schmidt, Gayliella flaccida (Harvey ex Kützing) T.O. Cho & L.M. McIvor, Ptilothamnion speluncarum (Collins & Hervey) D.L. Ballantine & M.J. Wynne and Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun & J.N. Norris), two green (Cladophora liniformis and Rhizoclonium riparium), and one brown (Sporochnus pedunculatus). In descending order, the substrates in which the species grew were: psammophytic (33%), followed by epilithic (32%), epizoic (19%) and epiphytic (16%) (Fig. 2). The species richness of macroalgae per reef in the PNAC is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Percentage of substrates occupied by the different groups of algae species (Ochrophyta, Rhodophyta and Chlorophyta) present in the Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico.

Figure 3: Graph showing the species richness per sampled reef, Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico.

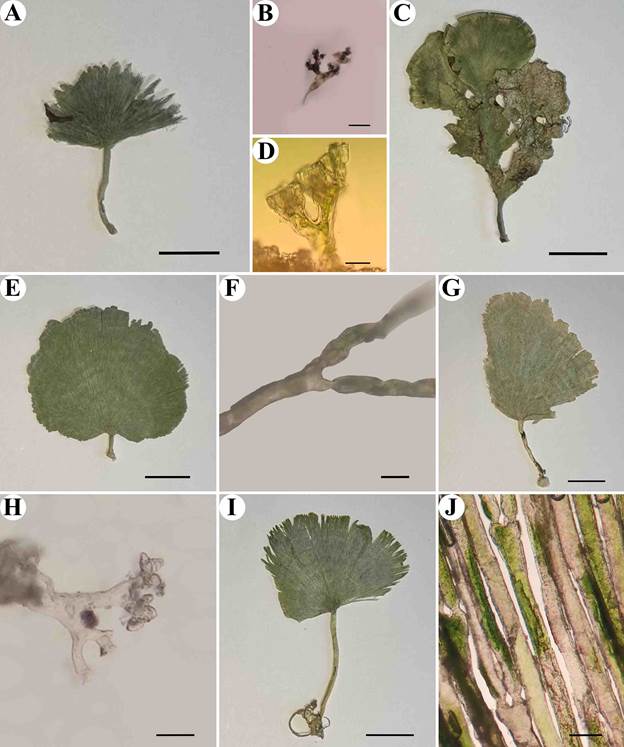

The morphological descriptions of the species, as well as the images associated with each one (such as thallus and anatomy) are presented systematically according to Wynne (2022).

Dictyotaceae

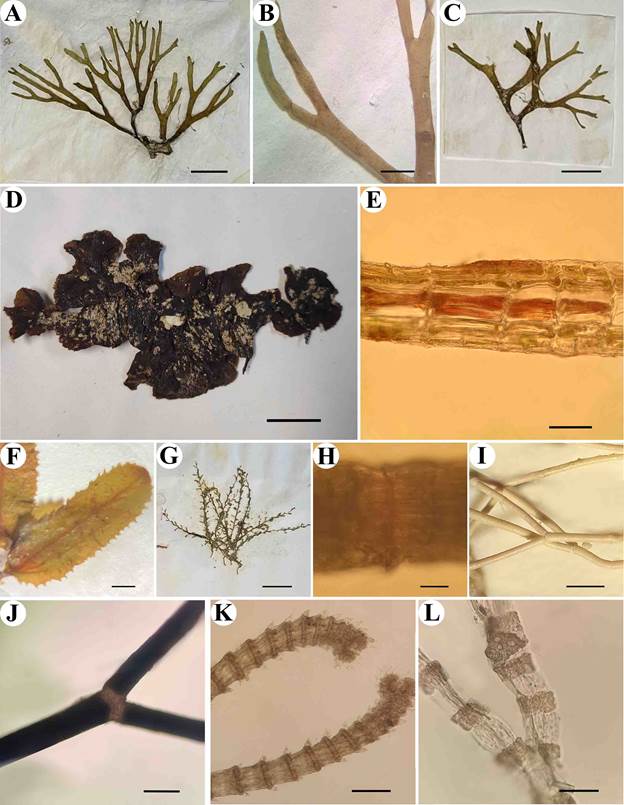

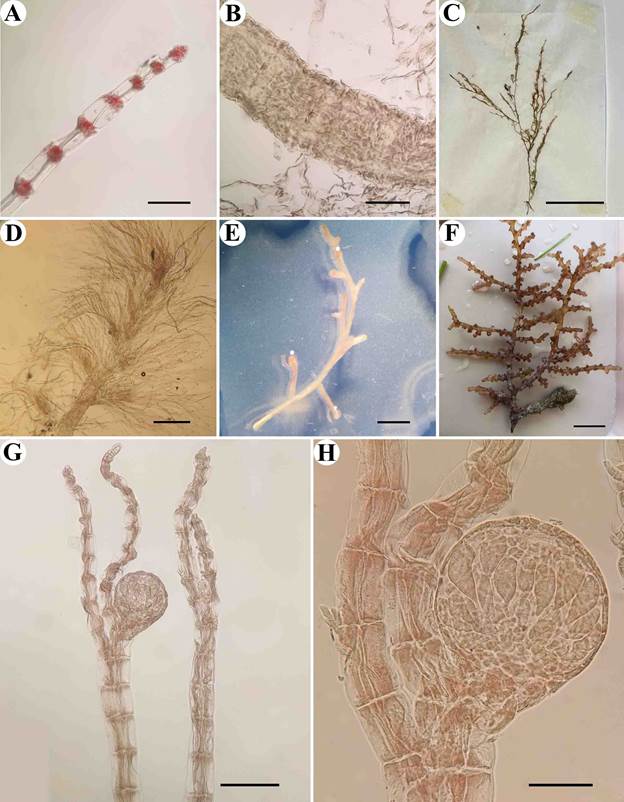

*Dictyota guineënsis (Kützing) P. Crouan & H. Crouan, 1878. Fig. 4A,B.

Figure 4: A-B. Dictyota guineënsis (Kützing) P. Crouan & H. Crouan: A. habit, scale bar=1 cm; B. branch detail, scale bar=4 mm; C. Dictyota pinnatifida Kützing: habit, scale bar=1 cm; D-E. Lobophora guadeloupensis N.E. Schultz, F. Rousseau & L. Le Gall: D. habit, scale bar=2.5 cm, E. longitudinal section of the sheet, scale bar=50 μm; F. Sargassum cf. cymosum C. Agardh: detail of the ramuli, scale bar=3 mm; G. Sporochnus pedunculatus (Hudson) C. Agardh: habit, scale bar=1.5 cm; H. Jania adhaerens J.V. Lamouroux: cells of the joint aligned longitudinally, scale bar=25 μm; I-J. Amphiroa fragilissima (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux: I. habit, scale bar=1 mm, J. branch joint, scale bar=300 μm; K. Centroceras clavulatum (C. Agardh) Montagne: nodes with spines and pincer-shaped apices, scale bar=200 μm; L. Ceramium luetzelburgii O.C. Schmidt: branch nodes and internodes, scale bar=70 μm.

Thallus 20-30 cm long, dark yellow to brown, bushy, erect; branching alternate proximally, dichotomous distally; blades 1-2.4 mm diameter, narrow strap-shaped; margins smooth, wavy; apices dichotomously branched, blunt or acute; medulla 2-3 cells thick, one cell thick at margins; cells 40-85 µm diameter, rectangular, arranged in rows; cortical cells 20 µm diameter.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1471; Reef La Francesa, depth 14 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1432.

*Dictyota pinnatifida Kützing, 1859. Fig. 4C.

Thallus 15 cm long, dark yellow to brown, erect; branching irregular to dichotomous; blades 4-5 mm diameter, strap-shaped; margins smooth; apices dichotomously branched, up to 45°, blunt or oblong; medulla 2-5 cells thick, thinnest in middle of lamina; cells 50-80 µm diameter, rectangular, arranged in two layers; cortical cells 10-20 µm diameter.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 21 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1472; Reef La Francesa, depth 14 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1433.

**Lobophora guadeloupensis N.E. Schultz, F. Rousseau & L.Le Gall, 2015. Fig. 4D,E.

Thallus 4 cm long, brown; blades 1-4 cm diameter × 1-3 cm long, fasciculate; in longitudinal section, medulla 2 cells thick, 80-100 µm diameter × 12.5-25 µm long; cortical cells four, two cells at each end, 80-100 µm diameter × 12.5-25 µm long.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tormentos, depth 19 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1434.

Sargassaceae

*Sargassum cf. cymosum C. Agardh, 1820. Fig. 4F.

Thallus 60-90 cm long, light brown to brown, forming bushes; main axes smooth or with some spines; leaves 3-8 mm diameter × 2-6 cm long, numerous, flat, narrow, firm; midrib prominent; margins notched; bases asymmetric; apices blunt or sharp; aerocysts numerous, round to oval, 3-6 mm diameter; terminal spine absent.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Paso del Cedral, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1435.

Sporochnaceae

*Sporochnus pedunculatus (Hudson) C. Agardh, 1817. Fig. 4G.

Thallus 20 cm long, light brown, stiff; branching irregular on main axis and branches; main shaft cylindrical, rigid 1 mm diameter; branches with twigs ending in fine filamentous tufts; filaments 3 mm long.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Jardines, depth 11 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1473; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1436.

Corallinaceae

Jania adhaerens J.V. Lamouroux, 1816. Fig. 4H.

Thallus 4 cm long, pink to white, brittle, in clumps; branching broadly dichotomous; branches 70-200 µm diameter, cylindrical, tapering slightly towards blunt apices; segments 70-200 µm diameter × 0.4-1 mm long, calcified; joints with 7-8 cells aligned longitudinally, flexible, not calcified.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Jardines, depth 11 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1474; Reef Dalila, depth 18 m, 28.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1437.

Lithophyllaceae

Amphiroa fragilissima (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux, 1816. Fig. 4I,J.

Thallus 8 cm long, reddish to pinkish white, fragile, calcareous, tangled, forming extensive tufts; branching regularly dichotomous, with acute angles, occasionally trichotomous; branches thin, brittle, cylindrical, 150-250 µm diameter × 0.2-0.9 mm long; flexible joints, without calcification; oblong apices.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1475; Reef Tunich, depth 10 m, 28.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1438.

Ceramiaceae

Centroceras clavulatum (C. Agardh) Montagne, 1846. Fig. 4K.

Thallus 12 cm long, light pink to reddish, filamentous; branching narrowly dichotomous; apices forked, slightly coiled inward, pincer-shaped surrounded by spines; branches 50-150 µm diameter, highly pigmented; segments 50-150 µm diameter × 250-500 µm long, with spines at each node; rectangular cells with uniform size, aligned longitudinally.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 21 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1453; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1476.

Ceramium luetzelburgii O.C. Schmidt, 1924. Fig. 4L.

Thallus 3-5 cm long, pink to reddish; branching dichotomous; uniseriate filaments in nodes; nodes 10-40 µm long × 20-80 µm diameter; quadrangular or triangular cells, with no obvious gap between rows of nodal cells; unicellular internodes 50-180 µm long × 20-60 µm diameter that are lost between the cortication of the youngest portions.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Colombia, depth 10 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1439; Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 26 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1477.

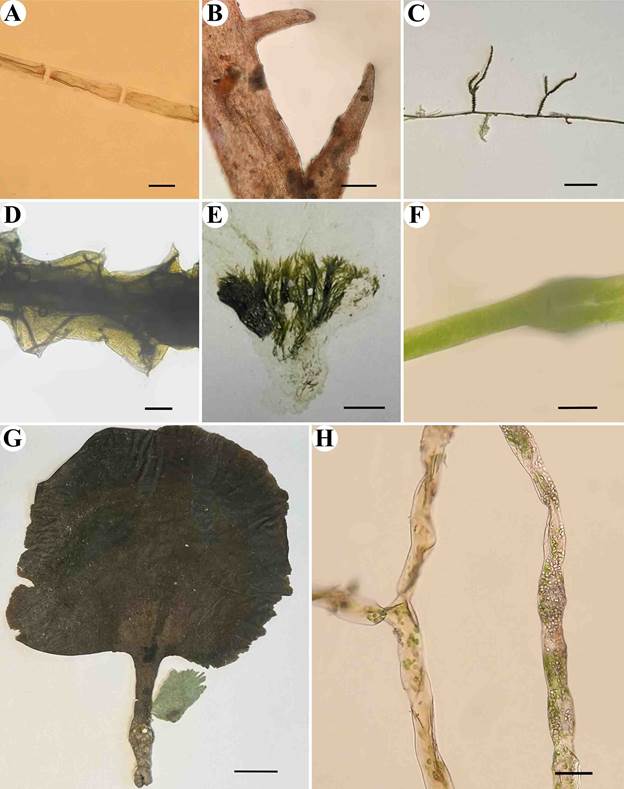

Gayliella flaccida (Harvey ex Kützing) T.O. Cho & L.M. McIvor, 2008. Fig. 5A.

Figure 5: A. Gayliella flaccida (Harvey ex Kützing) T.O. Cho & L.M. McIvor: nodes and branch apex, scale bar=100 μm; B. Dasya antillarum (M. Howe) A.J.K. Millar: ramula with opposite branching, scale bar=50 μm; C-D. Dasya pedicellata (C. Agardh) C. Agardh: C. habit, scale bar=2 cm, D. branches covered by branchlets, scale bar=1mm; E. Laurencia intricata J.V. Lamouroux: detail of the branch with spiral ramification, scale bar=3 mm; F. Yuzurua poiteaui (J.V. Lamouroux) Martin-Lescanne: habit, scale bar=1 cm; G-H. Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun & J.N. Norris: G. habit, scale bar=150 μm, H. cystocarp detail, scale bar=50μm.

Thallus 10 cm long, light pink to reddish, filamentous, dense, forming loose or dense tufts; branching irregular to pseudodichotomous; apices narrow distally, blunt to oblong, rarely pincer-shaped; segments 50-90 µm diameter × 100-300 µm long; joint cells arranged in 3-6 bands, upper 1-2 bands of small, round cells, lower 1-2 bands of transversely elongated cells.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1466; Reef La Francesa, depth 14 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1478.

Delesseriaceae

*Dasya antillarum (M. Howe) A.J.K. Millar, 1996. Fig. 5B.

Thallus 10 cm long, brown to reddish brown, delicate, bushy; branching irregular to pseudodichotomous; branches 1 mm diameter, bare proximally, covered with filamentous, hairlike branchlets distally; abundant cortication; branchlets 2 mm long, filamentous; tetrasporangial stichidia 200 µm diameter × 500 µm long, oval; tetrasporangia 50-60 µm diameter, spherical, tetrahedrally divided.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Dalila, depth 18 m, 26.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1440.

Dasya pedicellata (C. Agardh) C. Agardh, 1824. Fig. 5C,D.

Thallus 20 cm long, dark red; erect, delicate, soft; branching alternate on main axis; branches 8 mm diameter, slippery, long, graceful, completely cut, covered by fine bunches similar to hairs; completely corticated; branchlets 2-7 mm long; tetrasporangial stichidia 80-160 µm diameter × 0.5-1.2 mm long, lance-shaped; tetrasporangia 40-80 µm diameter, spherical, tetrahedrally divided.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1441; Reef Santa Rosa, depth 30 m, 28.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1479.

Rhodomelaceae

Laurencia intricata J.V. Lamouroux, 1813. Fig. 5E.

Thallus 15 cm long, brown, pink to reddish, fleshy, flaccid, gregarious, in loose mats; cylindrical; spiral branching, sparse, irregularly alternate; main axis not apparent; branches 0.4-0.8 mm diameter, cylindrical; apices slightly curved downwards, with tufts of fine, discrete filaments branching dichotomously in the terminal depression.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1480; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1442.

Yuzurua poiteaui (J.V. Lamouroux) Martin-Lescanne, 2010. Fig. 5F.

Thallus 20 cm long, brown with reddish tips, stiff, bushy, wiry; branching closely alternated in pairs to irregular; branches 0.5-2 mm diameter, cylindrical to slightly flattened; twigs 0.3-1 mm diameter × 0.5-2 mm long, numerous, clavate, cylindrical, wart-like, swollen, blunt to slightly oblong apices.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tunich, depth 18 m, 20.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1443; Reef La Francesa, depth 14 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1481.

Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun & J.N. Norris, 1982. Fig. 5G,H.

Thallus 2 cm long, brown to dark red, filamentous, soft, flaccid; branching, sparse, dichotomous; axes 60-90 µm diameter, four pericentral cells arising from axial cell; cortication absent; segments 60-90 µm diameter × 80-180 µm long; spherical tetrasporangia, cystocarps 150-300 µm diameter × 180-360 µm long, globular in shape.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1482; Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1444.

Wrangeliaceae

*Ptilothamnion speluncarum (Collins & Hervey) D.L. Ballantine & M.J. Wynne, 1998. Fig. 6A.

Figure 6: A. Ptilothamnion speluncarum (Collins & Hervey) D.L. Ballantine & M.J. Wynne: erect axis cells, scale bar=30 μm; B. Hypnea spinella (C. Agardh) Kützing: branchlest detail, scale bar=250 μm; C-D. Caulerpa cupressoides var. flabellata Børgesen: C. habit, scale bar=1 cm, D. branchlet detail, scale bar=2 mm; E-F. Derbesia marina (Lyngbye) Solier: E. habit, scale bar=5 mm, F. filament detail, scale bar=50 μm; G-H. Avrainvillea asarifolia Børgesen: G. habit, scale bar=2 cm, H. detail of the siphons of the lamina, scale bar=30 μm.

Thallus 1.2 cm long, light pink to reddish, filamentous; branching generally absent, when present sparse, dichotomous, or irregular; filaments 22-40 µm diameter, tapering distally; cells 20 µm diameter × 85-90 µm long; stolons 30-40 µm diameter, conspicuous, filamentous.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1445; Reef Dalila, depth 18 m, 26.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1483.

Cystocloniaceae

Hypnea spinella (C. Agardh) Kützing, 1847. Fig. 6B.

Thallus 3 cm long, light brown to reddish brown, fibrous, in matted mats; branching irregular in all directions; branches 0.4-1 mm diameter, cylindrical; branchlets 2-2.5 mm long, numerous, like thorns or spurs that cover the main axis and branches; apices tapering, pointed, not curved.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1484; Reef Tunich, depth 10 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1446.

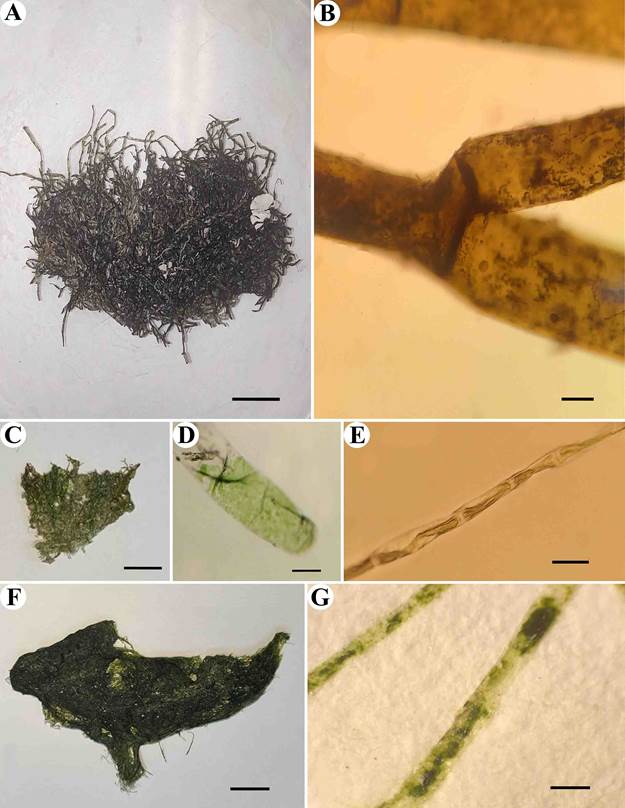

Caulerpaceae

*Caulerpa cupressoides var. flabellata Børgesen, 1907. Fig. 6C,D.

Stolon 20 cm long, creeping, with branched rhizoids, numerous; erect axes 2.5-7 cm long, yellow to dark green, rigid; branching irregular to somewhat dichotomous; branchlets 0.1-0.8 mm diameter, short, marginally spine-like, stiff, opposite; apices pointed.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tormentos, depth 12 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1485; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1447.

Derbesiaceae

Derbesia marina (Lyngbye) Solier, 1846. Fig. 6E,F.

Discrete rhizoid mass; thallus 1-3 cm long, dark green; fine filaments forming tufts; branching sparse, lateral, dichotomous; siphons 37-55 µm diameter, in the dichotomy 63 µm diameter; oblong apices.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1486; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1448.

Dichotomosiphonaceae

*Avrainvillea asarifolia Børgesen, 1909. Fig. 6G,H.

Thallus 9-20 cm long, solitary or in groups, 3-5 fronds, erect, dull greyish green to darkish green; stipe cylindrical flattened above, 6-9 mm diameter × 6-10 cm long; frond kidney-shaped, 13.5 cm diameter × 10 cm long, 12 mm thick, shallow zoning, margins irregular to gently rounded; interior siphons contorted to slightly moniliform 25 µm diameter.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tikila Norte, depth 8 m, 19.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1487; Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 26 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1449.

Halimedaceae

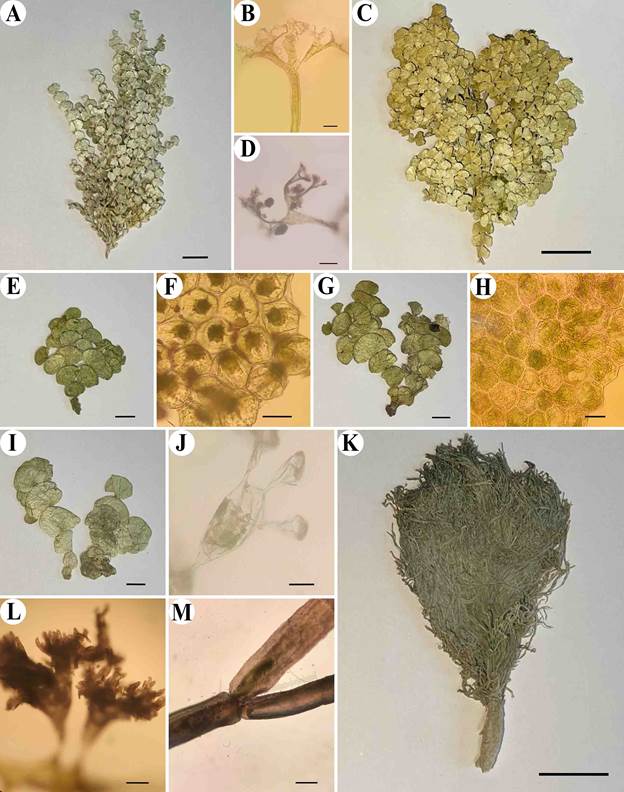

Halimeda copiosa Goreau & E.A. Graham, 1967. Fig. 7A,B.

Figure 7: A-B. Halimeda copiosa Goreau & E.A. Graham: A. habit, scale bar=1 cm, B. detail of the utricle, scale bar 15 μm; C-D. Halimeda opuntia (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux: C. habit, scale bar=2 cm, D. detail of the utricle, scale bar=100 μm; E-F. Halimeda scabra M. Howe: E. habit, scale bar=2 cm, F. utricles in superficial view, scale bar=30 μm; G-H. Halimeda tuna (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux: G. habit, scale bar=1 cm, H. utricles in superficial view, scale bar=40 μm; I-J. Halimeda tuna f. platydisca (Decaisne) E.S. Barton: I. habit, scale bar=1 cm, J. detail of the utricle, scale bar=30 μm; K-M. Penicillus dumetosus (J.V. Lamouroux) Blainville: K. habit, scale bar=2 cm, L. utricles, scale bar=250 μm, M. siphon dichotomy, scale bar=500 μm.

Thallus 10-30 cm long, pendulous, forming loose clumps or chains, bright green to whitish; branching mostly dichotomous, initially in one plane; segments highly calcified, oblong to oval ribbed, first 2-5 segments three-lobed, 0.4-2.1 cm diameter × 0.3-1.3 cm long; utricles 70-100 µm diameter; utricles in surface (apical) view 30-40 µm diameter; stipe not evident.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1488; Reef Dalila, depth 18 m, 26.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1450.

Halimeda opuntia (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux, 1967. Fig. 7C,D.

Thallus 10-20 cm long, forming dense clumps or mounds, greenish yellow to dark green; branching irregular; segments calcified, trilobed or ribbed, 0.9-1.1 cm diameter × 0.5-0.7 cm long; utricles 80-100 µm diameter; utricles in surface (apical) view 11-50 µm diameter; stipe not evident.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Chankanaab, depth 14 m, 19.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1489; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1451.

*Halimeda scabra M. Howe, 1905. Fig. 7E,F.

Thallus 5-15 cm long, erect, grey green; branching in one plane; segments slightly calcified, disc or wedge-shaped and rough surface, 2 cm diameter × 1.5 cm long; utricles 90-100 µm diameter with superficial spine; utricles in surface view 40-60 µm diameter; obvious stipe formed by fused segments.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1452; Reef Tormentos, depth 19 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1490.

Halimeda tuna (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux, 1816. Fig. G,H7.

Thallus 10-25 cm long, compact, dark green; initial branching in one plane; segments slightly calcified, disc-shaped, 2.3 cm diameter × 1.6 cm long; utricles 100-150 µm diameter; utricles in surface view 40-50 µm diameter; very evident stipe formed by fused segments.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 21 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1453; Reef Dalila, depth 18 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1491.

Halimeda tuna f. platydisca (Decaisne) E.S. Barton, 1901. Fig. 7I,J.

Thallus 7-15 cm long, compact, light to dark green; initial branching in one plane; segments slightly calcified, disc-shaped, 2-4 cm diameter × 2-4 cm long; utricles 90-100 µm diameter; utricles in surface view 55-65 µm diameter; stipe not evident.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1454; Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1492.

Penicillus dumetosus (J.V. Lamouroux) Blainville, 1830. Fig. 7K-M.

Rhizoidal mass prominent; thallus 10-15 cm long, bright green to dark green; stipe 15 mm diameter × 5-8 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the capitulum, calcified; utricles 500-1000 µm diameter, apices tapering to blunt points; capitulum brush-shaped, 3-6 cm diameter × 20-25 cm long; siphons 400-800 µm diameter, thick, equally constrained in all dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1455; Reef Paso del Cedral, depth 17 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1493.

Penicillus lamourouxii Decaisne, 1842. Fig. 8A,B.

Figure 8: A-B. Penicillus lamourouxii Decaisne: A. habit, scale bar=2 cm, B. dichotomy in the capitulum siphon, scale bar=150 μm; C-D. Penicillus pyriformis A. Gepp & E.S. Gepp: C. habit, scale bar=2 cm, D. detail of the utricle, scale bar=100 μm; E. Rhipiliopsis sp.: habit, scale bar=1 cm; F-G. Rhipocephalus oblongus (Decaisne) Kützing: F. habit, scale bar=2 cm, G. detail of the utricle, scale bar=200 μm; H-I. Rhipocephalus phoenix (J. Ellis & Solander) Kützing: H. habit, scale bar=2 cm, I. detail of the utricle, scale bar=100 μm; J-K. Udotea cyathiformis Decaisne: J. habit, scale bar=2 cm, K. laminate siphons, scale bar=200 μm; L-M. Udotea cyathiformis f. infundibulum (J. Agardh) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: L. habit, scale bar=2 cm, M. detail of the utricle, scale bar=100 μm.

Rhizoidal mass bulbous; thallus 6 cm long, bright green to dark green; stipe 15 mm diameter × 4-5 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the capitulum, calcified; utricles 500-1000 µm diameter, apices short, flat, finger-like, dichotomously divided; capitulum brush-shaped, 0.3 mm diameter × 2-4 cm long; siphons 300-500 µm diameter, thick, equally constrained in all dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 14 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1456.

Penicillus pyriformis A. Gepp & E.S. Gepp, 1905. Fig. 8C,D.

Rhizoidal mass bulbous; thallus 4-8 cm long, greyish green; stipe 5-7 mm diameter × 3-10 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the capitulum, highly calcified; utricles 400-500 µm diameter, apices finger-like tapering to blunt points; capitulum flat-cup shaped, 5-10 cm diameter × 2-5 cm long; siphons 150-200 µm diameter, rigid, entangled, constrained in all dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1494; Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1457.

Rhipiliopsis sp.Fig. 8E.

Rhizoidal mass discrete; thallus 4-6 cm long, light green, translucent; stipe 2−3 mm diameter × 1−2 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the blade; blade circular 2−3 cm diameter, margins rounded, smooth to finely ragged; siphons cylindrical, on layer thick.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1495; Reef Palancar Jardines, depth 18 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1458.

Rhipocephalus oblongus (Decaisne) Kützing, 1849. Fig. 8F,G.

Rhizoidal mass compact; thallus 3-8 cm long, dark green; stipe 2-6 mm diameter × 1-3 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the capitulum, calcified; utricles 200-250 µm diameter, apices short tapering to blunt points; capitulum cone-shaped to extremely elongate, 1-3 cm diameter × 2-5 cm long; siphons 150-200 µm diameter, slender, branching dichotomously at equal distances from the base.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1459; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1496.

*Rhipocephalus phoenix (J. Ellis & Solander) Kützing, 1843. Fig. 8H,I.

Rhizoidal mass compact; thallus 6-13 cm long, dark green; stipe 3-5 mm diameter × 2-5 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the capitulum, calcified; utricles 200-250 µm diameter, apices slightly elongate, tapering to blunt points; capitulum ovoid in shape, composed of narrow lamellae, 5-7 cm diameter × 5-8 cm long; siphons 200-250 µm diameter, slender, branching dichotomously at equal distances from the base.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1460; Reef Tunich, depth 10 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1497.

Udotea cyathiformis Decaisne, 1842. Fig. 8J,K.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 3-10 cm long; bright green to dark green; stipe 1-4 mm diameter × 1-6 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the lamina, calcified; utricles 100-200 µm diameter, apices short tapering to oblong points; lamina cup-shaped, delicate, thin, bark absent, zonation weak, 5-7 cm diameter × 2-8 cm long; siphons 30-70 µm diameter, constricted above dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1461; Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1498.

*Udotea cyathiformis f. infundibulum (J. Agardh) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 8J,M.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 5-7 cm long; dark green; stipe 1-4 mm diameter × 1-5 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the lamina, calcified; utricles 900 µm diameter, apices short, flattened; lamina cup-shaped, delicate, thin, bark absent, zonation weak, 1-3 cm diameter × 1-2 cm long; siphons 100-130 µm diameter, constrained above dichotomies.

Taxonomic comment: the description of the morphological characters corresponds to that reported by Littler and Littler (2000) except for the diameter of the siphons, which they reported as 30-70 µm diameter.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Santa Rosa, depth 26 m, 17.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1462; Reef Tikila Norte, depth 7 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1499.

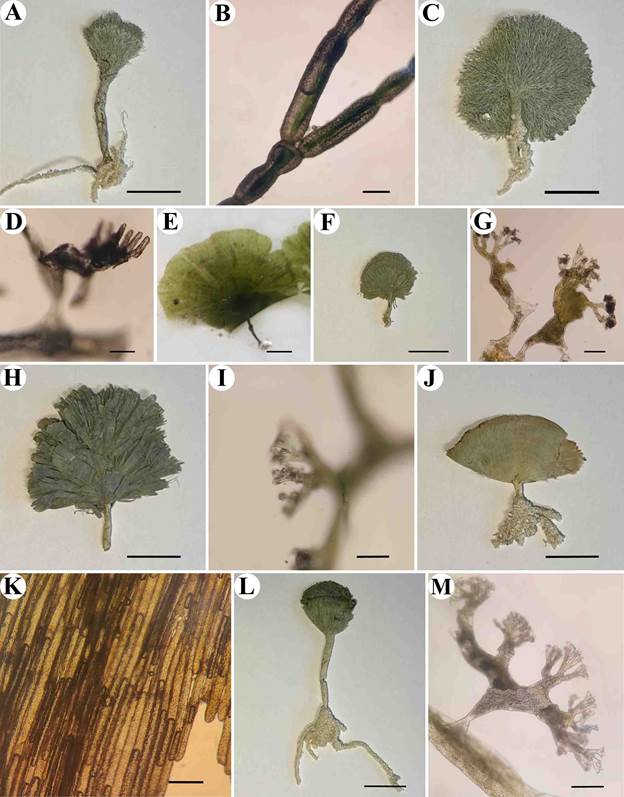

*Udotea cyathiformis f. sublittoralis (W.R. Taylor) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 9A,B.

Figure 9: A-B. Udotea cyathiformis f. sublittoralis (W.R. Taylor) D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: A. habit, scale bar=2 cm, B. detail of the utricle, scale bar=90 μm; C-D. Udotea dixonii D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: C. habit, scale bar=2 cm, D. detail of the utricle, scale bar=50 μm; E-F Udotea luna D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: E. habit, scale bar=2 cm, F. dichotomy in the lamina siphon, scale bar=100 μm; G-H. Udotea unistratea D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: G. habit, scale bar=2 cm, H. detail of the utricle, scale bar=50 μm; I-J. Udotea cf. unistratea D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler: I. habit, scale bar=2 cm, J. laminate siphons, scale bar=100 μm.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 4−7 cm long; dark green; stipe 1-4 mm diameter × 1-3 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the lamina, calcified; utricles 100 µm diameter, apices short, oblong; lamina cup-shaped, delicate, thin, bark absent, weak zonation, margins several layers thick, 3 cm diameter × 2 cm long; siphons 60-80 µm diameter, constrained above dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Palancar Ladrillos, depth 21 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1463; Reef Tormentos, depth 19 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1500.

Udotea dixonii D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 9C,D.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 8-15 cm long; light green to dark green; stipe 2-3 mm diameter × 1-6 cm long; transition between stipe and lamina not evident, slightly calcified; occurs in groups of up to six stems; erect axis 3-6 cm diameter × 3-7 cm long, multilayered, corticate; unconstrained siphons on dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef La Francesa, depth 13 m, 18.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1501; Reef Colombia, depth 27 m, 26.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1464.

*Udotea luna D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 9E,F.

Rhizoidal mass small; thallus 7 cm long; dark green; stipe 1-3 mm diameter × 1 cm long, gradual transition between stipe and lamina, slightly calcified; utricles 100-250 µm diameter with long apices, dichotomously acute; lamina fan-shaped to crescent, velvety texture, bark absent, weak zonation, 7-9 cm diameter × 5-6 cm long; siphons 50-80 µm diameter, constrained above dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tikila Sur, depth 8 m, 19.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1502; Reef Santa Rosa, depth 30 m, 28.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1465.

Udotea unistratea D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 9G,H.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 11 cm long; light green to dark green; stipe 1-2 mm diameter × 1-5 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the lamina, slightly calcified; utricles 200-300 µm diameter, apices short, oblong; lamina fan-shaped, bark absent, weak zonation, 6-7 cm diameter × 7-8 cm long; siphons 100-200 µm diameter, constrained above dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1466; Reef Paso del Cedral, depth 17 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1503.

*Udotea cf. unistratea D.S. Littler & M.M. Littler, 1990. Fig. 9I,J.

Rhizoidal mass fibrous; thallus 9 cm long; light green to dark green; stipe 1-2 mm diameter × 4-5 cm long, morphologically differentiated from the lamina, slightly calcified; utricles 250-500 µm diameter, apices short, oblong; lamina fan-shaped, bark absent, zonation weak, 8-10 cm diameter × 4-6 cm long; siphons 50-100 µm diameter, constrained above dichotomies.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef El Cedral, depth 23 m, 27.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1467.

Cladophoraceae

Cladophora catenata Kützing, 1843. Fig. 10A,B.

Figure 10: A-B. Cladophora catenata Kützing: A. habit, scale bar=1 cm, B. detail of the filament dichotomy, scale bar=300 μm; C-D. Cladophora liniformis Kützing: C. habit, scale bar=1 cm, D. detail of filament, scale bar=100 μm; E. Rhizoclonium riparium (Roth) Harvey, scale bar=20 μm; F-G. Ulva intestinalis Linnaeus: F. habit, scale bar=2 cm, G. filament detail, scale bar=5 mm.

Thallus 2-7 cm long, dark green, filamentous, rigid, erect to prostrated, in small, dense tufts; branching irregular, dichotomous to alternate towards the base, unilateral towards apex; maximum number of branches at joints one, rarely two; branchlets stiff; apices oblong; cells 160-300 µm diameter × 26-30 µm long.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Tikila Norte, depth 8 m, 19.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1504; Reef Chankanaab, depth 16 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1468.

*Cladophora liniformis Kützing, 1849. Fig. 10C,D.

Thallus 7 cm long, dark green, filamentous, like loose mats; branching appearing dichotomous towards the base, somewhat unilateral towards the apex; maximum number of branches at joints one, rarely two; apices straight or oblong; cells 20-40 µm diameter × 8-12 µm long.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1505; Reef Yucab, depth 17 m, 29.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1469.

*Rhizoclonium riparium (Roth) Harvey, 1849. Fig. 10E.

Thallus filamentous, yellowish green, tangled; unbranched or seldom branched, somewhat curled; filaments 7-15 µm diameter; cells rectangular 7-13 µm diameter × 30-40 µm long; apical cells often swollen or oblong.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Chankanaab, depth 14 m, 19.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1506; Reef Chankanaab, depth 16 m, 30.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1468.

Ulvaceae

*Ulva intestinalis Linnaeus, 1753. Fig. 10F,G.

Thallus 10-20 cm long, greenish yellow; blades cylindrical, or hollow tubular, flaccid, gregarious, 0.3-1.0 cm diameter; margins smooth, wavy, contoured towards apex, tapering towards base; cells with different shapes, rectangular with rounded edges, square, oval, and irregular.

Examined material: MEXICO, Quintana Roo, Cozumel, PNAC, Reef Yucab, depth 14 m, 16.X.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1507; Reef Colombia, depth 27 m, 26.XI.2018, L. G. Calva Benítez UAMIZ-1470.

Discussion

Phycofloristic diversity

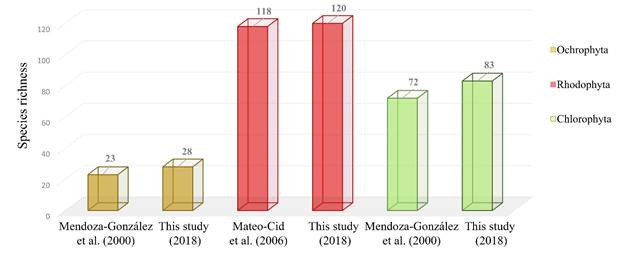

In the present study, a total of 42 species of macroalgae were recorded for the PNAC, which constitutes 20% of known algal diversity in the area (Fig. 11). Mendoza-González et al. (2000) previously reported 93 algae (22 Ochrophyta and 71 Chlorophyta) on PNAC reefs; of these, only 13 species of green algae were shared with this study. Mateo-Cid et al. (2006) reported 117 species of red algae, of which only nine were confirmed again in our results. Twenty-three species of the present study are shared with those of Mendoza-González et al. (2000) and Mateo-Cid et al. (2006) together. The species reported here represent 10% of the total of algal species recorded for Cozumel Island, while they constitute 4% for the Mexican Caribbean (Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González, 1991; Mendoza-González et al., 2000; Mateo-Cid et al., 2006; Cetz-Navarro et al., 2007; Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González, 2007). It is important to highlight that the studies previously carried out on the PNAC reefs only considered eight reefs that were sampled between 1993 and 1998. Therefore, the relevance of the present study consisted of the incorporation of 14 coral reefs sampled in 2018, including medium-depth reefs and wall reefs (up to 30 m), which contributes with timely and updated information to the phycoflora in the PNAC. For example, none of the new records presented here had been previously recorded in these reefs; also, other species (e. g. Halimeda copiosa) had been recorded only in one reef and here we extended their distribution ranges.

Figure 11: Accumulated records for flora in Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico, from studies carried out from 2000 to this study (2018), organized into Phaeophyta, Rhodophyta and Chlorophyta. By group, the bar on the left represents the accumulated records prior to this study and the bar on the right side represents the accumulated with the records provided in this study.

Richness and substrate

The algal species richness of the present study compared to that reported for Cozumel Island (Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González, 2007) was low, even with that registered for the PNAC (Mendoza-González et al., 2000; Mateo-Cid et al., 2006). These differences require considering several aspects: first, that the lists presented by Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González (2007) were the result of a compilation of previous works (Huerta, 1958; Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González, 1991; Mendoza-González et al., 2000; Mateo-Cid et al., 2006). In the present study, macroalgae were only collected from the coral reefs of the subtidal zone, taking into account four types of substrate: psammophytic, epilithic, epizoic, and epiphytic, thus considering that other substrates and/or habitats to be sampled are lacking; for example, those communities associated with seagrasses (Nava-Olvera et al., 2017) or mobile animals such as mollusks (Garduño-Solórzano et al., 2005). However, not all epiphytic species were included; we only considered the most frequent ones. Patiño-Espinosa et al. (2022) indicated that the diversity of benthic macroalgae was related to the type of substrate. For example, in sandy substrates, the diversity of macroalgae is lower than in epizoic (coral) or even epiphytic ones. In contrast, in this work in the PNAC, the predominant substrates were sandy and rocky. Another factor to consider is that in the present study, only conspicuous algae of more than 1 cm in length were considered. In this regard, Collado-Vides et al. (1998) mentioned that including small species (<1 cm) in the lists results in an overestimation of species, as observed in the lists of Mendoza-González et al. (2000), Mateo-Cid et al. (2006) and Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González (2007). This could offer an additional explanation about the difference in the number of taxa that have been recorded compared to what we report for the PNAC.

Seasonality

It should be noted that seasonality is another factor that has been studied in the PNAC reefs. In this regard, Mendoza-González et al. (2000) reported greater species richness in Chlorophyta and Ochrophyta during the rainy season than in the dry season. Likewise, Mateo-Cid et al. (2006) recorded a greater number of Rhodophyta algae during this season. Unfortunately, it was not possible to compare our results with previous reports from the dry season, since our sampling months (October and November) corresponded with the rainy season. However, according to Mendoza-González et al. (2000) and Mateo-Cid et al. (2006), in the rainy season the richness of Chlorophyta is greater than that of Rhodophyta and Ochrophyta, which coincides with our results where Chlorophyta had the greatest richness.

Phycofloristic affinity

The PNAC presented a tropical phycoflora typical of the Caribbean Sea. Most of the taxa described in this study had already been recorded in other reef areas of the state of Quintana Roo, such as Puerto Morelos, Isla Mujeres and the Biosphere Reserve Sian Ka’an, where the most common species are the following: Dictyota pinnatifida, Amphiroa fragilissima, Jania adhaerens, Dasya pedicellata, Centroceras clavulatum, Hypnea spinella, Avrainvillea asarifolia, Halimeda opuntia, H. scabra, H. tuna, Penicillus dumetosus, P. lamourouxii, Rhipocephalus phoenix and Udotea cyathiformis f. sublittoralis (Collado-Vides et al., 1998; Quan-Young et al., 2004; Valadez et al., 2014; Acosta-Calderón et al., 2016). Commonly, red algae constitute the dominant group in the phycoflora from the coastal regions of the Mexican Atlantic (Mateo-Cid et al., 1996; Galicia García and Morales García, 2007; Mendoza-González et al., 2007; Cetz-Navarro et al., 2007; Sánchez-Molina et al., 2007; Godínez-Ortega et al., 2009; Mendoza-González et al., 2016; García-García et al., 2020; Cuevas Sánchez et al., 2022; Patiño-Espinosa et al., 2022). In contrast, in the PNAC, Chlorophyta had the highest species richness (26 species), which is probably due to the affinity to the substrate. In this sense, Santelices (1977) mentioned that the hard substrate allows the establishment of Bryopsidal green algae. Likewise, Acosta-Calderón et al. (2016) point out that in sandy substrates it is common to find species of the Halimedaceae; rhizophytic algae that have a fixation system that allows them to adhere to unstable substrates and consolidate (Aguilar-Rosas et al., 2001). This is relevant, since it explains the presence of 92% of the Chlorophyta species that were located on a sandy and/or rocky substrate, which was observed as calcareous platforms, rocks of different sizes, and rocky areas with prominences and cavities (Underwater Editions, 2003). A similar panorama was presented in the Puerto Morelos reef system (Collado-Vides et al., 1998), in the Parque Nacional Arrecifes Xcalak (CONANP, 2004), on the Banco Chinchorro (González and Torruco, 2015) and along the rocky Neovolcanic coastline of Veracruz (Landa-Cansigno et al., 2019) where green algae were the most diverse.

Abiotic factors

It is important to mention that, although light is a major factor whose influence is observed in the distribution of macroalgae, with green algae predominating in shallow reefs and red algae in deep reefs (Roth, 2014), in the present study, the light factor did not have a determining effect. In contrast, although the reefs sampled were at depths of 7 to 30 m, green algae predominated in all reefs. Therefore, the dense aggregates of lamellar algae (Ulva intestinalis) distributed at depths of 23 to 30 m, referred to by Rioja-Nieto et al. (2012), could be related to nutrient contributions that originate from the percolation of wastewater of hotels, which are usually discharged into the subsoil, as well as anthropogenic contributions derived from the population increase on the island, taking into account that there is only one wastewater treatment plant (PMDC, 2021). Likewise, the concentration of carbonates can explain the presence of qualifying species at these depths, as is the case of Halimeda J.V. Lamouroux whose species are calcifying and, therefore, of global importance, since they are strongly associated with coral reef habitats (van Tussenbroek and Barba Santos, 2011; Wizemann et al., 2015; Mayakun and Prathep, 2019). These algae are key members of reef communities, providing vital ecological functions, such as stabilization of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary productivity, and trophic support (Hallock, 2001; Wizemann et al., 2015; Sansone et al., 2017; Mayakun and Prathep, 2019). However, it should be noted that, despite the importance of these algae in reef structures, in most reef phycofloristic records, calcifying green algae occur in a lower proportion, compared to other algal groups (Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González, 2007; González-Solis et al., 2018; Cruz-Francisco et al., 2020; Piñón-Gimate et al., 2020; López Gómez et al., 2022; Patiño-Espinosa et al., 2022).

Species of the genus Udotea J.V. Lamouroux showed an affinity for sand and in some cases were recorded on rocks, like brown algae. The species of the genus Halimeda were recorded mainly attached to the rocky substrate. In particular H. copiosa was identified growing exclusively on rocks; these macroalgae occur as formations in chains that hang vertically below rocky ledges (Littler and Littler, 2000). Patiño-Espinosa et al. (2022) recorded growth of Halimeda spp. in the Parque Nacional Arrecifes Xcalak on sand and coral skeletons. On the Mexican coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, species of Halimeda have been found on psammophytic and epizoic substrates (Garduño-Solórzano et al., 2005). Unlike what has previously been described, in the PNAC they have been observed growing on rocks, sand and sessile animals (sponges and corals). González-Gándara et al. (2007) mentioned that habitats with shallow waters and a sandy substrate favor the growth of species of Halimeda and Udotea. However, in this study, species of these genera were identified at depths of up to 30 m or in habitats with little light (caves, cracks or fissures in rocks), which is similar to that recorded by Mendoza-González et al. (2000).

Epiphytic diversity

With respect to epiphytic species, we identified twelve, nine of which were strictly so (Appendix). This number is lower compared to what was reported on the coasts of Quintana Roo by Aguilar Rosas et al. (1998), Mateo-Cid and Mendoza-González (1991) and Quan-Young et al. (2006), who reported that the high degree of epiphytism is a common situation in the regional flora. The difference could be related to the characteristics of the substrate and tidal level, since those studies refer to hard substrates at depths of up to 2 m, while in the present one, epiphytic algae were identified at depths of up to 30 m and growing mainly on the thallus of other macroalgae. In addition, not all epiphytic algae were identified, only those with the highest incidence, which could have inferred the number of species recorded.

Distribution peer reef

Regarding the distribution of species per reef studied, it was observed that Dictyota pinnatifida, Halimeda copiosa, Penicillus dumetosus, Penicillus pyriformis, Rhipocephalus phoenix, Udotea cyathiformis and Udotea cyathiformis f. infundibulum occurred in all the reefs, while Dictyota guineënsis, Lobophora guadeloupensis, Caulerpa cupressoides var. flabellata, Penicillus lamourouxii, Udotea cf. unistratea, Cladophora catenata, Cladophora liniformis and Rhizoclonium riparium only in some of them. This provides important information on the biology of the species (life cycle, reproduction, physiology or morphology) and offers an explanation of their possible distribution patterns, which determine their presence or absence in relation to type of substrate (Hernández et al., 2021). With respect to the collection season, although there were differences in the number of species reported, there were no evident differences in the species composition or the type of substrate in which each species proliferated, which remained homogeneous over time.

Finally, this study, in addition to offering specific information on the species present in 14 PNAC reefs, is the first contribution for the island of Cozumel that includes morphological descriptions and photographic references of the species recorded, information that can be used in other future studies such ecology, biogeography and conservation of marine macroalgae. However, it is essential to continue with these studies that can facilitate the constant monitoring of the biotic elements of the PNAC that, in turn, allow determining the state of health of the reefs and guarantee a sustainable management of the ecosystem, considering that it is an area economically important for its characteristics in terms of flora and fauna composition, which favors the development of sports, recreational, tourist and fishing activities that make it a site of human interest. Likewise, it is important to carry out phycofloristic studies that integrate molecular tools with detailed characterizations that allow estimating the real species richness of the area and contribute robustly to the integration of knowledge of the diversity of Mexican marine algae.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)