Introduction

Mexico is a country with vast knowledge about the use of wild edible fungi species extending back to pre-Hispanic times (Dubovoy, 1968). The traditional consumption of numerous ectomycorrhizal species collected as edibles in forested areas throughout the country is notable, but especially in the central region where the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt is present (Herrera and Guzmán, 1961; Martínez-Alfaro et al., 1983; Bandala et al., 1997; Montoya-Esquivel et al., 2003). Fruit bodies of edible fungi are widely used in the country including, for example, Boletus spp., Amanita spp., Cantharellus spp., Russula spp., and Ramaria spp. (Herrera and Guzmán, 1961). There are also species of other genera used in localized areas of Mexico such as the tropical Lactifluus chiapanensis (Montoya, Bandala & Guzmán) De Crop (Montoya et al., 1996; De Crop et al., 2017) (locally named Moní) and Tremelloscypha gelatinosa (Murrill) Oberw. & K. Wells (Wells and Oberwinkler, 1982) (locally named Nangañaña) in Chiapas (southern Mexico) (Montoya et al., 1996; Bandala et al., 2014). A special case is the Mexican Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude species related to T. matsutake (Ito & lmai) Sing., first recorded by Montoya-Bello et al. (1987) in the Cofre de Perote mountain or Nauhcampatépetl (Náhuatl=mountain of the four sides) in Veracruz state, under the name T. ponderosum (Sacc.) Sing. ((a prior illegitimate name for T. magnivelare (Peck) Redhead (1984)).

Tricholoma matsutake is an edible mushroom highly valued for its organoleptic characteristics and medicinal properties, related to its metabolomic diversity, which comprises around 800 bioactive molecules, such as amino acids, peptides, carbohydrates, terpenoids, organic heterocyclics, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, steroids, and fatty acids with their derivatives (Li et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2022). Zeller and Togashi (1934) considered T. ponderosum (as Armillaria ponderosa Sacc., now T. murrillianum Sing.) as the “American matsutake”, a valuable edible species in the United States of America (USA) according to Thiers and Sundberg (1976). The record of the occurrence of matsutake relatives in the Cofre de Perote mountain by Montoya-Bello et al. (1987) attracted attention from Mexican academics and Japanese vendors and, consequently, this previously unnoticed species became a highly prized edible mushroom, beginning to be recognized under the vernacular names “hongo blanco de ocote” or simply “hongo blanco” (white mushroom), “hongo canela” (cinnamon mushroom), “hongo de rayo” (lined mushroom), “hongo rico” (tasty mushroom), and “tanaca” (Japanese family name) (Bandala et al., 1997; Jarvis et al., 2004). This fungus attracted much interest and became subject to large-scale commercial harvesting in many parts of the country.

On the Cofre de Perote Mountain, where ancestral knowledge of edible mushrooms prevails, this white mushroom was not traditionally used before 1987. After the aforementioned record, its use grew in conjunction with a Japanese trading company paying relatively high prices by local standards for this previously non-valuable species (Bandala et al., 1997; Jarvis et al., 2004). With this new knowledge, a change of perception arose among the native population about this and other wild edible mushrooms. Until the 1980s the ethnomycological culture of the area recognized a list of about 50 species known with descriptive vernacular names in Nahuatl or Spanish (Guzmán and Villarreal, 1984; Villarreal and Guzmán, 1985; Jarvis et al., 2004), but after the discovery of that Tricholoma species and the increasing commercial demand from foreign buyers of edible mushrooms, a new intensive and selective exploitation of mushrooms arose in the area (Bandala et al., 1997), even adopting European or Asiatic names for different species, both in the countryside and in popular markets in urban areas around that mountain. For example, restaurant owners, chefs, and local resellers were already referring to edible mushrooms with names, such as porcini, white matsutake, etc., although most of the species collected and traded locally do not correspond to the species originally known from Europe, Asia or even the United States of America. Some of these names are currently replacing vernacular names in the markets.

After the 1987 record of the supposed “T. magnivelare”, a new business model emerged, and locals began to sell this species to intermediaries or directly to foreign buyers for exportation or distribution to other areas of the country. Parallel to the new demand for the white mushroom, other edible species also began to be offered for sale, and the collection practices in the area were modified, seeking to accumulate larger quantities to sell. Today, unlike in the past, it is less common for sellers to have direct contact with buyers in the popular markets where mushrooms are sold. The native peoples’ purpose for collecting mushrooms also has changed. Originally it was only for family consumption or for small-volume sales in baskets or buckets directly in surrounding towns or local markets in the city of Xalapa, located about 64 km from the mountain.

Tricholoma magnivelare according to Trudell et al. (2017) has been found only in North America and is paler in color in contrast to T. matsutake. These authors described from Mexico, T. mesoamericanum Justo & Cifuentes which, together with its sister species T. magnivelare and T. murrillianum Singer, represent the matsutake group in North America (Ota et al., 2012; Trudell et al., 2017). Carpophores of T. mesoamericanum by these authors were collected in different regions of Mexico, including sites in the states of Chihuahua, Guerrero, Hidalgo and Oaxaca (type locality). Recently, Sandor et al. (2020) carried out an analysis of the mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and a phylogeographic analysis of the species of the matsutake complex at a global level, in which they found consistency between the phylogenies obtained from the different molecular markers of mitochondrial DNA and the phylogeny obtained with the ITS molecular marker.

The objective of this work was to determine the taxonomic identity of fresh samples of one Tricholoma gathered in the Cofre de Perote region and adjacent areas and samples collected in a forest from Puebla that macroscopically reminded T. magnivelare, T. mesoamericanum and T. colposii Pérez-Moreno, Martínez-Reyes & Ayala-Vásquez. Based on the molecular evidence (that includes type specimens of the three species) and on the color and morphological (macro-microscopic) features in the new fresh collections we concluded that all specimens studied corresponds to T. mesoamericanum and that T. colposii should be reduced to synonymy. Our results agree with other authors (Trudell et al., 2017) in that T. magnivelare s. str. occurs in eastern USA and Canada. So far, it has not been recorded in Mexico, and until now, the recorded matsutake species in Mexico, which also occurs in the southwestern USA, is T. mesoamericanum.

Material and Methods

Sampling and morphological study

Ten explorations during 2009 and 2018 in two different sites in the states of Puebla and Veracruz, Mexico were carried out for the collection of Tricholoma samples. At the Cofre de Perote mountain, in the municipality Las Vigas, Veracruz, the study site is located at an elevation of 2520-2870 m, covered with conifer forests dominated mainly by Pinus ayacahuite Ehren., P. montezumae Lamb., P. patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. and P. pseudostrobus Lindl. The climate is cold subhumid to mild subhumid with average annual temperatures between -3-18°C and average annual rainfall between 200-1800 mm (Fuentes-Moreno et al., 2017). In the northeast of the state of Puebla, in the municipality Tlatlauquitepec, the sampling area is located at 2792 m, covered with conifer forests dominated by P. pseudostrobus. In addition, fructifications bought in the Alcalde y García market in Xalapa, popularly known as the San José market, were also studied. Vendors mentioned that such fruit bodies “came from the Cofre de Perote”.

The specimens obtained in the field and the market were studied with respect to measurements, colors and morpho-anatomical and organoleptic characteristics. Colors recorded follow Munsell (1994) (e.g., 2.5Y 8/2-4) and Kornerup and Wanscher (1978) (e.g., 4A4). A micromorphological study was carried out on the preserved samples using a Nikon ECLIPSE Ci (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) compound microscope with a drawing tube. The microscopic study was done in slides mounted in 3% KOH and stained with 1% Congo red. Thirty-five basidiospores per collection were measured in lateral view, following Montoya et al. (2019b). In the descriptions X̅ denotes an interval of mean values of basidiospore length and width per collection in n collections, and Q̅ refers to the range of coefficient Q (where Q is the average of the ratio of basidiospore length/basidiospore width in each collection).

Collections form part of the herbarium XAL (Thiers, 2022) of the Instituto de Ecología, A.C. in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico.

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

DNA was obtained from the collected basidiomes following the method of César et al. (2018). The Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region of ribosomal DNA was amplified using the primers ITS1F and ITS5/ITS4 (White et al., 1990; Gardes and Bruns, 1993). Sequencing of the amplified PCR products was performed by Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea. All the sequences obtained (Table 1) were edited, assembled, and deposited in GenBank (Benson et al., 2017).

Table 1: Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude taxa included in this study: samples, location and GenBank accession number for ITS sequences; those in bold represent sequences generated in this study and their vouchers were deposited in the XAL herbarium.

| Taxon | Voucher/strain | Location | GenBank |

| Hypsizygus marmoreus (Peck) H.E. Bigelow | HMW1 | Malaysia | HM561970 |

| Tricholoma anatolicum H.H. Doğan & Intini | HD1058 TYPE | Turkey | MF612194 |

| Tricholoma bakamatsutake Hongo | Syntype no. 1283 TYPE | Japan | AB699657 |

| Tricholoma caligatum (Viv.) Ricken | TB-2010-MEX 48 | Mexico | KC152249 |

| Tricholoma caligatum (Viv.) Ricken | CM030 | Algeria | KC565866 |

| Tricholoma caligatum (Viv.) Ricken | JV07-451 | Spain | LT000152 |

| Tricholoma caligatum (Viv.) Ricken | PH99-519 | France | LT000079 |

| Tricholoma colposii J. Pérez-Moreno, M. Martínez-Reyes M. & O. Ayala-Vásquez O. | MEXU 30413 TYPE | Mexico | OM732326 |

| Tricholoma colposii J. Pérez-Moreno, M. Martínez-Reyes M. & O. Ayala-Vásquez O. | MEXU 30414 | Mexico | OM732327 |

| Tricholoma colposii J. Pérez-Moreno, M. Martínez-Reyes M. & O. Ayala-Vásquez O. | MEXU 30415 | Mexico | OM732328 |

| Tricholoma colposii J. Pérez-Moreno, M. Martínez-Reyes M. & O. Ayala-Vásquez O. | MEXU 30416 | Mexico | OM732329 |

| Tricholoma dulciolens Kytöv. | H: 7002022 TYPE | Sweden | AB738883 |

| Tricholoma forteflavescens Reschke, Popa, Zhu L. Yang & G. Kost | HKAS: 93511 TYPE | China | NR_160587 |

| Tricholoma fulvocastaneum Hongo | CMU 25007 | Thailand | DQ067895 |

| Tricholoma fulvocastaneum Hongo | TN6941 | Japan | AB289668 |

| Tricholoma ilkkae Mort. Chr., Heilm.-Claus., Ryman & N. Bergius | UPS: F-513823 TYPE | Sweden | NR_159051 |

| Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead | Ich | Mexico | AF309525 |

| Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead | Ich | Mexico | AF309527 |

| Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead | ICh Ixtepeji | Mexico | AF309531 |

| Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead | ICh San Andres | Mexico | AF309530 |

| Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead | NYS f2421 TYPE | USA | LT220177 |

| Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer | ATCC 64715 | Japan | AF309536 |

| Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer | NBRC: 6932 | Japan | AB699626 |

| Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer | Y1 | Japan | AB036890 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum Justo & Cifuentes | Bandala 4461 | Mexico | OL813480 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Bandala 4462 | Mexico | OL813481 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Bandala 4463 | Mexico | OL813482 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Bandala 4465 | Mexico | OL813483 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Bandala 4466 | Mexico | OL813484 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | César 131 | Mexico | OL813485 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | César 140 | Mexico | OL813486 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | César 152 | Mexico | OL813487 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | César 180 | Mexico | OL813488 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | JLF7803 | USA | OL810985 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Mata 951 | Mexico | OL813489 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Montoya 4769 | Mexico | OL813490 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Montoya 5437 | Mexico | OL813491 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | USA | MK301255 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | Ramos 738 | Mexico | OL813492 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | FCME: 21585 TYPE | Mexico | KX037037 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | FCME: 21585 TYPE | Mexico | MN088531 |

| Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes | FCME: 21585 TYPE | Mexico | NR_166291 |

| Tricholoma murrillianum Justo & Cifuentes | NY 586560 TYPE | USA | LT220179 |

| Tricholoma murrillianum Singer | SAT-16-319-01 EPITYPE | USA | KY660032 |

| Tricholoma murrillianum Singer | TR85 | USA | KX037030 |

| Tricholoma olivaceum Reschke, Popa, Zhu L. Yang & G. Kost | HKAS: 93513 TYPE | China | NR_160588 |

| Tricholoma rapipes (Krombh.) Heilm.-Claus. & Mort. Chr. | MC98-106 TYPE | France | LT000085 |

| Tricholoma sp. | Mex1 | Mexico | AB510472 |

| Tricholoma sp. | MX1 | Mexico | AB699647 |

| Tricholoma sudum (Fr.) Quél. | MC98-601 TYPE | Denmark | LT000051 |

Phylogenetic analyses

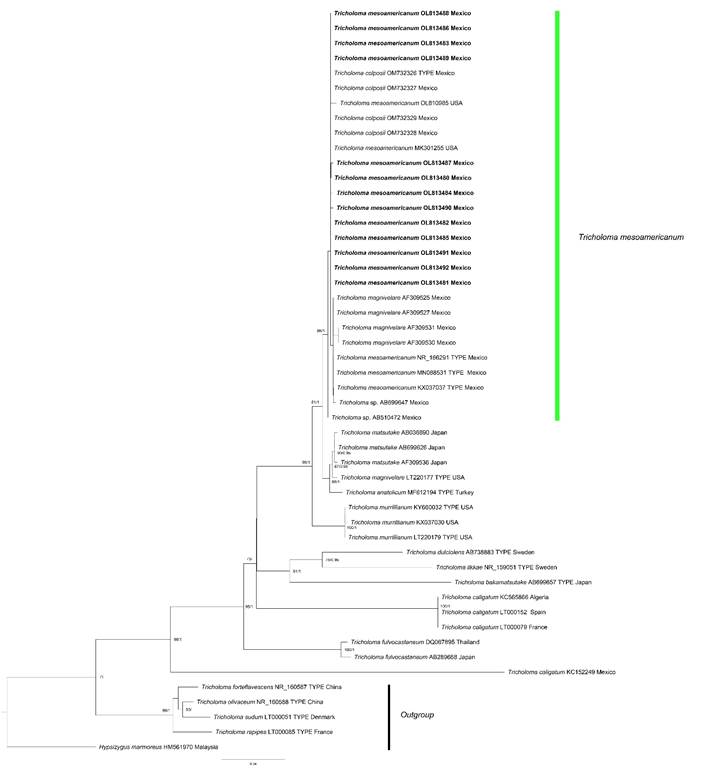

Phylogenetic trees were generated following the method of Montoya et al. (2019a). A dataset, using PhyDE v. 0.9971 (Müller et al., 2010) was constructed with the sequences obtained in this study, together with sequences of taxa related to Sect. Caligata Konrad & Maubl. ex Bon from GenBank (Benson et al., 2017). The dataset was aligned with MAFFT online service (Katoh et al., 2019) and inconsistencies were corrected manually. The evolutionary model was calculated using the IQ-Tree v. 2.1.1 package (Nguyen et al., 2015; Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017; Minh et al., 2020) and the best-fitting model was selected using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and corrected AIC. This later was used to generate a phylogenetic tree in IQTree v. 2.1.1 with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method, with a Nearest Neighbour Interchange (NNI) heuristic, with the HKY+F+G4 evolutionary model. A consensus tree by ML and another phylogenetic tree by Bayesian Inference (BI), using MrBayes v. 3.2.7 (Ronquist et al., 2012) were also generated according to Montoya et al. (2019a). The phylogenies from ML and BI analyses were displayed using FigTree v. 1.4.4 (Rambaut, 2018) and whose topologies were similar and consistent. In the phylogeny from ML analyses of figure 1, only bootstrap values (BS) of ≥70% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) of ≥0.90 were considered and indicated on the tree branches (BS/BPP).

Results

A total of 13 ITS sequences obtained from the freshly collected basidiomes were used to perform phylogenetic analysis together with sequences downloaded from GenBank (Table 1). The pre-existing Mexican samples labeled as T. mesoamericanum (including the type collection), T. colposii (including the type collection), and “T. magnivelare” along with those studied here, form a clade sister to T. matsutake, the T. magnivelare type specimen, and T. anatolicum H.H. Doğan & Intini (Fig. 1), which strongly supports that all Mexican collections represent T. mesoamericanum. This result also informs about the wide morphological variation exhibited by basidiomes of this species in color and macro- and micromorphological features. Interestingly, two sequences from specimens collected in conifer forests in Coconino and Cochise counties, Arizona, USA and deposited in GenBank (Table 1, Fig. 1), were also recovered in the T. mesoamericanum clade, indicating that the distribution of the species extends beyond Mexico.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic relationships within Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude species inferred from ITS rDNA sequences, by maximum likelihood method. The new sequences generated here are indicated in bold. Bootstrap scores (≥70) and Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (≥0.90) are indicated above the branches.

Taxonomy

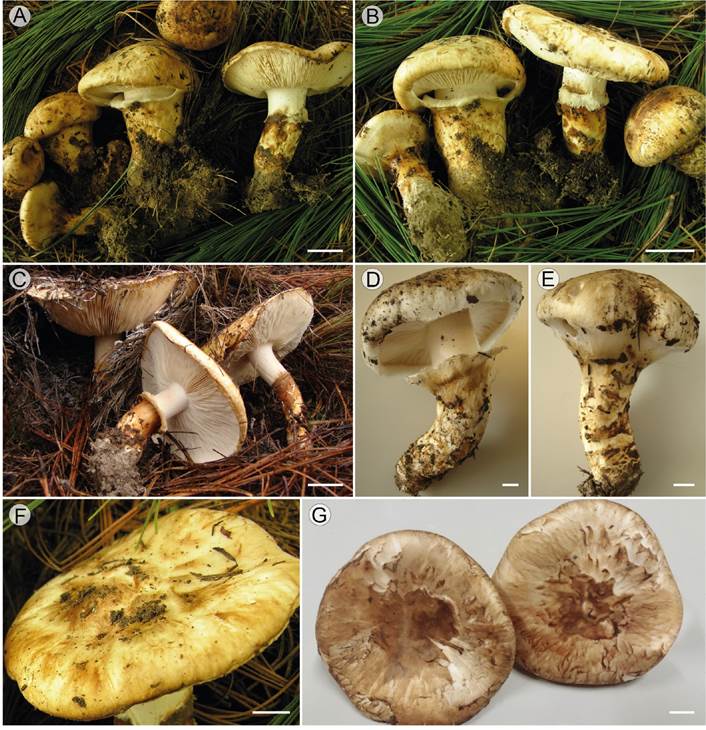

Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes , Mycologia 109: 385. 2017.Figs. 2, 3, 4.

Figure 2: Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes basidiomes A, B, F. L. Montoya 4769 (XAL); C. V.M. Bandala 4461 (XAL); D-E. V.M. Bandala 4465 (XAL); G. L. Montoya 5437 (XAL). Bars: A-C = 20 mm, D-G = 10 mm.

Figure 3: Microscopic features of Tricholoma mesoamericanum Justo & Cifuentes. A, B. basidiospores (A. L. Montoya 4769 (XAL); B. E. César 131 (XAL)); C. basidia; D-E. cheilocystidia-like elements of lamellae edge (C-E. L. Montoya 4769 (XAL)). Bars: A-B = 5 μm, C-E = 10 μm.

Figure 4: Tricholoma mesoamericanum & Cifuentes pileipellis. A. E. César 131 (XAL); B. L Montoya 4769 (XAL). Bars: 25 µm.

TYPE: MEXICO. Oaxaca, Ixtlán de Juárez, north of “Rancho de Los Torres.” 1.VIII.2005, Cifuentes 2005-130 (holotype: FCME 21585). Gene sequences ex-holotype: ITS KX037037.

= Tricholoma colposii J. Pérez-Moreno, M. Martínez-Reyes M. & O. Ayala-Vásquez O., Phytotaxa 542(1): 27. 2022.

= Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead, Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan 25(1): 6. 1984. auct. Mex.: Montoya-Bello et al. (1987); Villarreal and Pérez-Moreno (1989); Bandala et al. (1997); Martínez-Carrera et al. (2002); Jarvis et al. (2004); Zamora-Martínez and Nieto de Pascual-Pola (2004); Edouard et al. (2006); Pérez-Moreno et al. (2008); Gaitán (2012).

Iconography: Villarreal and Pérez-Moreno (1989: 134, Fig. 1; 142, Fig. 7); Martínez-Carrera et al. (2002: 34, Figs. 7-8); Edouard et al. (2006: 55, Fig. 3.13); Trudell et al. (2017: 384, Fig. 2d-e); Ayala-Vázquez et al. (2022: 28, Fig. 2); Clements and Fulton (2022); Frank (2022).

Pileus (18-)35-110 mm diam., primordia subhemispheric, expanding to convex, plane-convex when mature, slightly broadly umbonate or slightly depressed in some mature specimens, lubricous to dry, surface soft, hygrophanous, silky or shiny, mostly with compact cuticle at pileus center, innate fibrillose towards margin, sometimes with a squarrose appearance, forming flat innate squamules with a tendency to be disposed in radial arrangement or towards the margin, the edge of those squamules at times lifted; surface in the primordia dull, ivory white to dirty cream, with yellow, greyish-yellow or yellow-brown tinges (4A4; 2.5Y 8/2-4, 10YR 7/6), darker in some areas (4B4-5), others pale ochraceous (6C5; 10YR 6-7/6), pinkish-brown (10YR 7/3, 8/2) or even darker (6C6; 7.5 YR 5/3); mature specimens whitish, with yellowish-cream (4A3-A2; 2.5Y 8/3-2) or yellowish-ochraceous (10YR 7/6) areas over a whitish background, or some areas with brownish-orange (5B6), flesh (7.5YR 7/3-4), or reddish-brown (5YR 4/4) tinges; in more mature specimens, irregularly beige, with brownish (6D5-E6), pinkish or reddish, dark flesh (7.5YR 3-4/4), orange-brown (5B5, 5C6; 10YR4/6) or brownish tinges, at the center of the disc becoming orange-brown (7.5 YR 4/6) with dark vinaceous-brown tinges (5YR 3/3); cuticle lifting easily and showing the white context; squamules developing gradually pinkish-brown or reddish-brown (5YR 3/4), orange-brown (6E8; 5YR4/6) or brown-vinaceous (7B6, 7D7-8, 7E8; 2.5YR 3/6, 5/4, 4/3-4) tinges over a cream yellow ground (2.5Y 8/3-4); margin membranous, involute, decurved, squarrose, edge tomentose, even or appendiculate with veil remnants; veil a cover extending from the stipe base, the primordia entirely covered, at times somewhat gelatinous to the touch, membranous, even elastic, external surface fibrous, yellowish-white to cream color or whitish, beige yellowish to ochraceous (10YR 7/6), concolorous with stipe surface or darker brown due to the adhesion of soil or debris; in mature specimens only with remnants or hanging inversely from the stipe as a partial subapical veil, fixed, simple, membranous-squamous, interior tomentose, as the pileus expands becoming ragged, fibrillose, in some even fibrillose arachnoid, with the same colors of the stipe surface or darker brown due to the adhesion of soil or debris and yellowish in the inner surface; lamellae adnate to sinuate, when pileus expands the lamellae can be detached from the stipe or develop a tooth, close to crowded, undulate, narrow, 2-6 (-8) mm width, of different width in a same basidiome, edge not fimbriate, sinuous, with a tendency to wrinkle, some bifurcate, ivory with some pinkish reflections (paler than 10YR 8/2), white, whitish-cream (paler than 4A2) unstained, thin, somewhat leathery, with lamellulae of at least three tiers, 0-2 between two lamellae; margin rugose, more whitish and thinner; stipe 40-80 × 15-40 mm, subcylindrical, equal, tapering downwards, sinuous, central or eccentric, fleshy fibrous, solid, frequently hollow, primordia covered by an innate veil, this with the same colors as the stipe surface, the surface of the stipe when mature pruinose at apex, the remaining surface innately fibrillose and adpressed squamulose, at times squarrose or even with leopardine appearance, dry, fibrous, white especially towards the apex, some pale grayish-brown areas (5CD5), squamules amber-brown (6C7; 10YR 6/6-8), pinkish-brown (7.5YR4-5/4), below the ring yellowish or concolorous with pileus (nearly 10 YR 8/4), pale ochraceous-orange or darker (7.5YR 4/4, 5/6; 10YR 4-5/6) over the cuticle, not detachable as that of the pileus, somewhat lubricous or sticky, base with abundant rhizomorphs; context of pileus fleshier than the stipe, more fibrous towards the stipe, easily disentangled in fibrous elements as cooked chicken breast, white, unchanging; odor intense, fragrant, agreeable, spicy, somewhat Pelargonium-like, or pine resin, or with sweetish cinnamon to chocolate notes; taste resembling pine nuts, very pleasant; basidiospores (5-) 5.5-9 × 4-6 (-6.5) µm, X̅ = 6.1-7.3 × 4.5-5.4 µm; Q̅ = 1.31-1.50, broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, inamyloid; basidia 31-52 × 5-9 μm, mostly 4-spored, but 1-3-spored frequent, clavate, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth; pleurocystidia absent; cheilocystidia-like elements (14-) 21-47 (-53) × 3-8 µm, cylindrical, sinuous, slightly tortuous, frequent, at times ampullaceous or even bifurcate at apex, thin-walled, hyaline, smooth; pileipellis a somewhat gelatinized cutis, compact, composed of cylindrical hyphae, 3-9 µm diam., hyaline to pale-yellowish, at times with yellowish contents, yellowish in group, thin-walled, smooth, rarely forming small squamules; pileus context regular to subregular, hyphae 6-20 (-25) diam., cylindrical to inflated, hyaline, smooth, thin walled (˂1 µm), some with yellowish oil content; lamellae trama regular, hyphae 7-19 µm diam, cylindrical to inflated, hyaline, thin walled, hyaline, smooth; stipitipellis in cutis, with hyphae compactly arranged, ungelatinized, pale yellow in group, cylindrical, 4-12 µm diam., hyaline, but dextrinoid after some minutes in Melzer reagent , thin-walled; stipe context, subcompact to compact, hyphae irregular to regularly interwoven, hyaline, 4-6 µm diam., some 8-12 µm, thin-walled; veil with subcylindrical to subventricose, hyaline, inamyloid, ungelatinized, thin-walled hyphae 6-15 µm diam., loosely and irregularly arranged.

Habit and habitat: on soil, solitary, scattered or in small groups, basidiomes often arising partially or totally covered by pine needles, in conifer forests under pines, especially P. pseudostrobus and P. montezumae.

Material examined: MEXICO. Puebla, municipality Tlatlauquitepec, ejido Gómez - Tepeteno, 4.XI.2009, V. M. Bandala 4461 (XAL), 4462 (XAL), 4463 (XAL), 4465 (XAL), 4466 (XAL). Veracruz, municipality Las Vigas, San Juan del Monte, 29.VIII.2018, E.César 131 (XAL); loc. cit., 12.IX.2018, E. César 140 (XAL); loc. cit., 22.X.2009, L. Montoya 4769 (XAL). Municipality of Perote, Ejido 20 de Noviembre, 5.X.1983, S. Chacón 1727A (XAL). Municipality of Xalapa, Alcalde y García Market, 9.VIII.2018, D. Ramos 738 (XAL); loc. cit., 15.XI.2018, E. César 180 (XAL); loc. cit., 20.IX.2018, E. César 152 (XAL); loc. cit., 8.IX.2016, G. Mata 951 (XAL); loc. cit., 2.VIII.2018, L. Montoya 5437 (XAL).

Distribution: in Mexico this species has a wide distribution through the states of Chihuahua, Durango, Guerrero, Hidalgo, México, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, and Veracruz. In the United States of America (USA) it is known from the state of Arizona.

Remarks: the pileus of fresh specimens studied here acquired brownish-orange, even reddish-brown or dark vinaceous brown tinges, with a decidedly squarrose appearance, with the edge of the squamules becoming lifted and notably developing brownish or even reddish-brown colors. The lamellae were yellowish white or yellowish cream at times with faint pinkish tinges, contrary to the white, spotted brown in age lamellae described by Trudell et al. (2017). Microscopically the basidiospores of studied specimens are somewhat larger than those reported by Trudell et al. (2017) (4.5-6.5 × 3.5-4.5 μm), the basidia are 4-spored (31-52 × 5-9 µm vs. 22-38 × 4.5-6.5 μm), with 1-3 frequent sterigmata, and exhibiting cheilocystidia-like sterile elements. All these variants of the basidiomes, together with the records in the literature in Mexico (under “T. magnivelare”), show that T. mesoamericanum has a moderately extensive range in color, combined with details of its pileus/stipe surfaces, and its macro- and microscopic morphological features. Basidiomes supporting T. colposii, recently described from Mexico (Cofre de Perote in Veracruz), show a similar set of macro- and micromorphological features, that in fact, since T. mesoamericanum and T. colposii are molecularly related, would be the morphological variation expected to be exhibited by a single taxon. Tricholoma colposii was morphologically characterized by “…middle size basidiomata, with orange brown to brown pileus and stipe, squamose when young and with appressed scales in maturity, cylindrical, fibrillose to scaly stipe, with globose to ellipsoid (4.5-) 5-6 (-7) × (3-) 4-5 (-6) μm smooth spores, sweet fruit odor …” (Ayala-Vásquez et al., 2022). Important information on the macroscopic variation of the basidiomes is also provided by the images of the specimens found in Arizona by Clements and Fulton (2022), and Frank (2022), where the lamellae and ornamentation of pileus and stipe and their colors are shown in detail. Based on our molecular analyses, we observe a discrepancy with the results on T. colposii by Ayala-Vásquez et al. (2022). In the latter research it was reported that after a BLAST analysis, they obtained a similarity percentage of 94% between a single sequence (of four) of ITS (668 bp) of T. colposii with T. mesoamericanum. However, our BLAST analysis showed a rank of similarity percentage of 99.66-99.82% among the four sequences of T. colposii by Ayala-Vásquez et al. (2022) with the type of T. mesoamericanum, and 100% similarity percentage with one sequence identified as T. matsutake from Mexico (AB036891). Furthermore, in the phylogeny obtained in such research, T. colposii appears in a well-supported clade, on a relatively long branch, as sister to T. mesoamericanum, which is not consistent with the great similarity among the sequences, observed through BLAST analysis. Our results show in fact a different tree topology and BS/BPP values, that prevent support for the proposal of T. colposii as an independent taxon.

The scaly aspect of the basidiomes of Tricholoma mesoamericanum may recall to some stages of development of T. magnivelare or even some similarity with T. matsutake. However, the latter two species are molecularly distant from T. mesoamericanum. The American T. magnivelare does not develop reddish or vinaceous colors on the pileus surface, or in the squamules, and its lamellae appear spotting or bruising reddish-brown with age (vs. unstaining in T. mesoamericanum). The pileus of T. matsutake was described with sepia tones, disk becoming tawny, russet or even developing darker tinges (dark brown), broader lamellae (10-12 mm) and shorter basidiospores (3-8 × 3-6 μm) (Zeller and Togashi, 1934).

Discussion

In their attempt to define the presence and geographic distribution of phylogenetic groupings within the core of species around T. matsutake, Chapela and Garbelotto (2004) recognized a separation between sequences of T. magnivelare from the eastern USA and those from central (Estado de Mexico) and southern Mexico (Guerrero and Oaxaca) that formed a closely but distinct clade. The separation between T. magnivelare and the specimens from Mexico potentially representing a different taxon was also recognized by other authors that referred to it as “Tricholoma sp.” (Yamada et al., 2010; Ota et al., 2012; Murata et al., 2013). With the four ITS sequences of specimens from Oaxaca, Guerrero and Estado de Mexico (Table 1), including a new one of the specimen FCME 21585 (KX037037) from Oaxaca and one from an isolate of unknown provenance in Mexico (AB699647 by Ota et al., 2012) (Table 1), Trudell et al. (2017) supported their proposal of T. mesoamericanum as a distinct species, being the only one of the three matsutake species in North America known to occur in Mexico. The other two are T. murrillianum from the western USA/Canada, and T. magnivelare from the eastern USA/Canada. The phylogeny obtained here with the 13 ITS sequences from fresh specimens studied, together with sequences of T. mesoamericanum available in GenBank (type specimen FCME 21585 included) (Table 1) yielded consistency in the clade T. mesoamericanum, in congruence with previous aforementioned studies, where the sequences that give support to T. colposii from Mexico are strongly embedded, suggesting that the specimens of it display part of the macro-microscopic variation belonging to a same species. Therefore, T. colposii is reduced to a synonym of T. mesoamericanum.

The results suggest that the Mexican species is found geographically separated from its close relatives and in ecosystems with different phytobiont complexes. Evidently, there are still few collections and explorations that have not been carried out in the areas where the different species could co-occur. Tricholoma mesoamericanum is present in the states of Chihuahua, Durango, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Mexico, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, and Veracruz, showing a western tendency in its distribution along the Sierra Madre Occidental and having a central west-east distribution almost following or around the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Fig. 5). Among the matsutake group, T. murrillianum is recognized to occur in the western USA and Canada, with some records in southern California (Trudell et al., 2017). Based on ITS sequences analyzed here, it is found that T. mesoamericanum extends into Arizona (central and southeastern) in the fragmented forest cover of the extreme north of the Mexican Sierra Madre Occidental, probably representing the northwestern limit of T. mesoamericanum (Fig. 5), possibly coexisting with T. murrillianum in the California-Arizona region. The basidiomes being whiter and becoming less scaly would distinguish T. murrillianum from T. mesoamericanum. In Arizona, T. mesoamericanum has been found under Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson (ponderosa pine), Pinus strobus L. (white pine), Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco (Douglas-fir) and Quercus gambelii Nutt. (gambel oak). In Mexico, the species in the sampled areas occurs with Pinus ayacahuite, P. montezumae, P. patula and P. pseudostrobus, but in other areas of the country it has been observed in forests of pines or mixed pines-oaks close to trees of Pinus teocote Schlecht & Cham., P. douglasiana Martínez, P. leiophylla Schiede & Deppe, P. patula var. longepedunculata Loock ex Martínez, P. rudis Endl., and P. oaxacana Mirov. with presence of Quercus crassifolia Née, Q. laurina Humb. et Bonpl., Q. conzattii Trel., Q. rugosa Née, and Q. scytophylla Liebm., and occasionally with trees of Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham. (Villarreal and Pérez-Moreno, 1989; Martínez-Carrera et al., 2002; Zamora-Martínez and Nieto de Pascual-Pola, 2004; Trudell et al., 2017). Additional to what Sandor et al. (2020) mentioned, the matsutake populations not yet sequenced, especially those collected in the North of the country, deserve to be analyzed to confirm their position in the phylogeny.

Conclusions

Tricholoma mesoamericanum is until now the only species of the T. matsutake group that has been recorded in Mexico, having as synonym the Mexican T. colposii. Currently there is no evidence that T. magnivelare occurs in Mexico.

We confirmed the sale of T. mesoamericanum in Xalapa city, through the collections bought in the market Alcalde y García, an important traditional point of sale of mushrooms in the region for people coming from rural areas near the city. We have confirmed through personal communication with the sellers that the mushroom offered in the market is collected in the Cofre de Perote area.

After more than three decades subsequent to the first record of a matsutake species in Mexico (Montoya-Bello et al., 1987), it was evident that the commercialization of this fungus has enriched the economy of the collectors from that region. In fact, other edible mushrooms fetched higher prices and, as discussed above, a new sales structure also emerged. However, the effects of the exponential growth of collection and sale have not been evaluated by studies on the status of fungal populations combined also with research on the state of conservation and sustainability of forests. These studies are necessary to promote measures in favor of sustainable development and a fair remuneration for the local inhabitants involved in the management of matsutake mushrooms.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)