Introduction

Habitat destruction and biodiversity loss are occurring worldwide. Approximately 12.5% of the global vascular flora is facing extinction (Brummitt et al., 2015; Robertson et al., 2020). Threatened species are typically restricted to hotspots mainly in the tropics, regions of high species richness, high level of endemism, and lack of reserves to protect species (Myers et al., 2000), as well as the presence of few botanic gardens (Westwood et al., 2020), since most botanic gardens are located in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, but very few in the tropics. Historically, biodiversity hotspots covered approximately 12% of the earth surface, but today these areas are restricted to 1.4% (Pironon et al., 2020). Hence, there is an expectation that many species within these areas are already under some threat of extinction (Brooks et al., 2002). The protected area networks for regions of high plant diversity are insufficient in order to attain effective conservation (Parga et al., 1996). Therefore, botanic gardens as a “lifeboat” strategy represent an opportunity to achieve effective plant conservation worldwide (Chen and Sun, 2018; Smith, 2019).

Today, there are approximately 3000 botanic gardens in the world (Westwood et al., 2020). These institutions cultivate approximately six million accessions of living plants, representing around 100,000 taxa in cultivation, which represent one-third of the estimated number of vascular plant species in the world (Golding et al., 2010; Sharrock and Jones, 2011; Smith, 2019; Sharrock, 2020; Westwood et al., 2020). Botanic gardens also serve as a global repository within easy reach of the public, students, and professionals alike, for documented plant ex situ collections and associated information resources: herbaria, books, journals, and electronic databases (Aronson, 2014). Utilizing knowledge from fieldwork and ecological research, botanic gardens contribute to ensuring that restoration projects include taxonomic diversity and incorporate plants of known genetic provenances (Crane et al., 2009; Oldfield, 2011). Botanic gardens inspire, inform, and educate broad audiences. Also, they offer the opportunity to conserve plant diversity in ex situ collections and have an important role in preventing species extinctions through conservation actions (Aronson, 2014; Mounce et al., 2017).

For this work, we will outline the contribution of the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden (JBC), an in situ botanic garden of 7.5 ha in tropical montane cloud forest in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico, towards plant conservation of Mexican Flora. The JBC, founded in 1977, was assessed by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, during its creation and can be considered an “offspring” of Kew (Vovides et al., 2010). The JBC is an in situ regional botanic garden, devoted to local floras with an emphasis on research, conservation, education, and propagation of threatened species, a concept largely born from the 1975 Kew Conference on Conservation of Threatened Plants (Simmonds et al., 1976). The Botanic Garden is home to two important National Collections: 1) The National Cycad Collection, which is made up of 1353 specimens distributed among 57 species. In Mexico there are 61 known species of native Cycads, 93% of the Mexican species are represented in the collection, and at least one species of the other known world genera. 2) Another important collection is the National Collection of Native Bamboos of Mexico of which 57 species are known; this collection consists of 45 species and 279 specimens. One of the main missions of the JBC is ex situ conservation of local flora and that of similar ecosystems. Education and outreach are important actions the JBC undertake owing to its close interaction with the public, that range from casual visitors for recreation to professionals and students at all scholarship levels. Like many gardens, the JBC runs courses and workshops on plant cultivation and gardening for the general public, as well as formal courses leading to diplomas. The botanic garden has outreach programs, including the assessment of rural nurseries aimed at sustainable management of ornamental cycads such as Dioon edule Lindl. and Zamia furfuracea L.f. at Monte Oscuro, Veracruz, Mexico, about 30 km from the garden; since 1990, this program has been extended to similar nurseries in Chiapas for additional cycad species and Chamaedorea Willd. palms (Vovides et al., 2002; 2010).

In this study, we explore how vascular plant diversity is currently conserved in the Botanic Garden and how well this is performing with respect to the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, specifically Target 8, which calls for “at least 75% of threatened plant species in ex situ collections, preferably in the country of origin” (GSPC; BGCI 2002; Blackmore, et al., 2011; Sharrock, 2020), as well as the Mexican Strategy for Plant Conservation (MSPC; CONABIO, CONANP and SEMARNAT, 2008). Also, we quantify the number of threatened species in the JBC and propose actions to further the research, conservation, and education work of the Botanic Garden.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

We used data from the Clavijero Botanic Garden scientific living collection stored in BG-BASE (O’Neal and Walter, 2000). We gathered information on species names, endemism, endangered status according to national and international policies, and field data (i.e., geographical coordinates, location, habitat, soil type, collection date, collector) associated with each species. We also looked in our database for scientific studies that used plant material from our collection to describe new plant species. For threatened plants, we used BGCI’s ThreatSearch (BGCI, 2020). This database is the most comprehensive database of conservation assessments of plants, it also includes the official IUCN Red List of Threatened Species version 2020 (IUCN, 2020), as well as the Mexican red list (SEMARNAT, 2010). In the case of the IUCN Red List, we only searched for all threatened species listed as Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable. Threatened species exclusively from tropical montane cloud forest were defined according to The Red List of Mexican Cloud Forest Trees (González-Espinosa et al., 2011).

Data processing

For all datasets, records were filtered to remove undescribed taxa. We interpret scientific living collections to include accessions that are maintained as part of an active cultivation cycle. We discarded records of horticultural taxa such as cultivars, due to the difficulties of taxonomic standardization, and because we were interested in biological species of wild origin. We normalized the taxonomy of records using R package Taxonstand v. 1.8 (Cayuela et al., 2012), so all taxa match an accepted or unresolved taxon listed by The Plant List v. 1.1 (The Plant List, 2013). For consistency and comparability, only species-level taxa were retained for analysis; subspecies and varieties were discarded.

Results

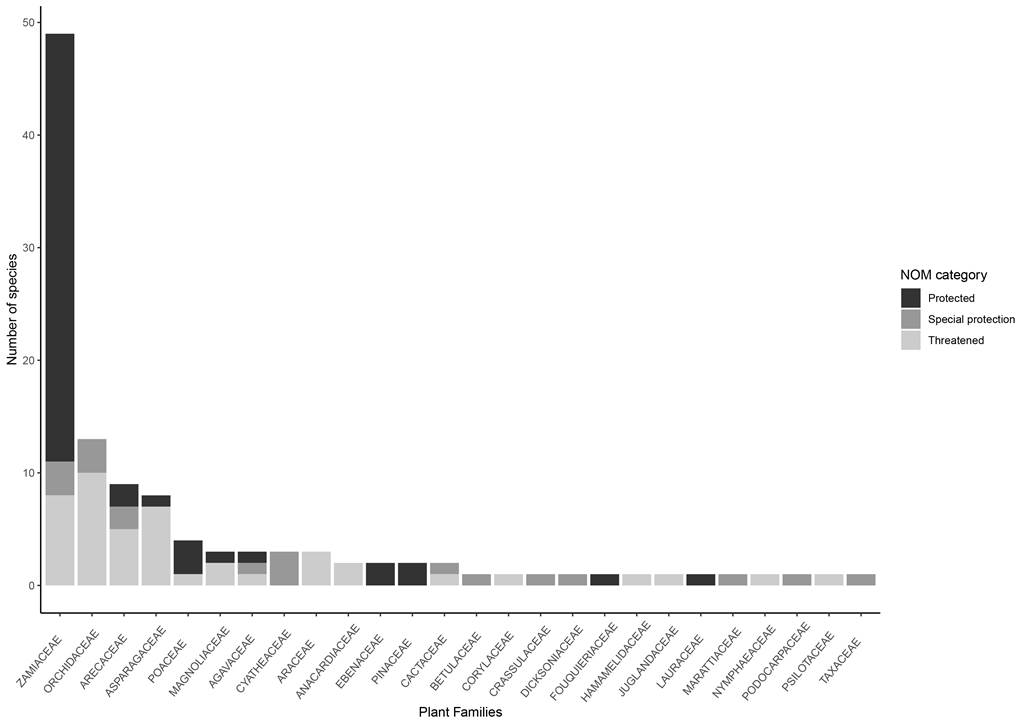

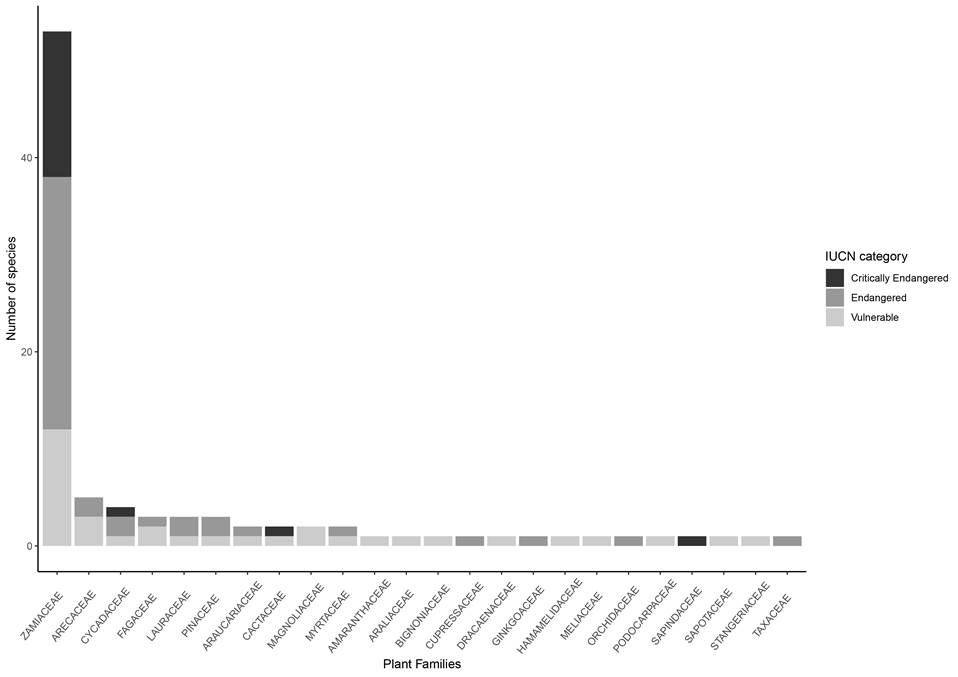

Overall, the JBC keeps 6222 individuals of plants with field collection information, belonging to 1009 species, 480 genera, and 152 plant families. The best-represented families are Orchidaceae, Zamiaceae, and Poaceae (133, 92, and 69 species, respectively). From all these species we have an important number of plants protected by the Mexican law NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010). For instance, the JBC is home of 1601 individuals of 117 species in some extinction risk category; this means that 12% of the entire collection consists of threatened species. Interestingly, plant families with more species at risk in the Botanic Garden collection are Zamiaceae, Orchidaceae, Arecaceae, and Asparagaceae (49, 13, 9, and 8 species, respectively; Fig. 1). Similarly, the JBC scientific collection has over 2048 individuals of 193 species in a threatened conservation category, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2020), which represents 32% of the entire collection. Plant families with most threatened species were Zamiaceae, Arecaceae, and Cycadaceae (53, 5, and 4 respectively; Fig. 2). Specifically, we detected 95 highly threatened species (18 Critically Endangered, 41 Endangered, and 36 Vulnerable) of 24 botanical families in the collection (Fig. 2). The plant family with the largest number of highly threatened species was Zamiaceae (15 Critically Endangered, 22 Endangered, and 12 Vulnerable species).

Figure 1: Number of plant families from the scientific living collection of the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico, with more species (n=117) under some risk category by Mexican law (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010; SEMARNAT, 2010).

Figure 2: Number of plant families from the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden collection, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico with highly threatened species (n=95) according to the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2020).

Another important plant group is the endemic species collection. The JBC collection has 26 plant species endemics to Mexico and 17 species endemics to Veracruz, which represent 28 and 12% of the total reported, respectively. The best-represented family endemic to Mexico is Orchidaceae and the best-represented family endemic to Veracruz is Zamiaceae (five and seven species, respectively).

Mexican plant species from the tropical montane cloud forest

Our analysis revealed that only 1731 (28%) of the 6222 individuals had associated data identifying habitat provenance (i.e., type of vegetation). Tropical cloud mountain forest, sub-evergreen medium forest, and tropical perennial rainforest are the best represented vegetation types in our collection (697, 349, and 222 individuals, respectively). At the other extreme, coastal dunes, riparian vegetation, and dessert are ecosystems with low numbers of individuals (19, six, and two, respectively).

According to the Red List of Mexican Cloud Forest Trees (González-Espinosa et al., 2011), 60 species in the scientific collection of the JBC are represented by 456 specimens classified as Endangered. For instance, Ostrya virginiana (Mill.) K. Koch (Betulaceae), Tapirira mexicana Marchand (Anacardiaceae), Oreopanax capitatus (Jacq.) Decne. & Planch. var. capitatus (Araliaceae), O. echinops (Schltdl. & Cham.) Decne. & Planch., and O. xalapensis (Kunth) Decne. & Planch. are threatened tree species representative of the cloud forest ecosystem, which are currently in the collection. In contrast, Quercus crassifolia Bonpl. (Fagaceae), Q. laurina Bonpl., Clethra mexicana DC. (Clethraceae), Palicourea padifolia (Roem. & Schult.) C.M. Taylor & Lawrence (Rubiaceae), and Alnus acuminata Kunth (Betulaceae) are cloud forest species of Least Concern (Table 1).

Table 1: Tropical cloud montane forest threatened species in the Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden collection, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. Risk categories in the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010) are as follows: P = Protected, SP = Special protection, and T = Threatened. Risk categories for the IUCN red list (IUCN, 2020): CR = Critically Endangered, E = Endangered, and V = Vulnerable.

| Plant family | Species | Number of individuals | NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 | IUCN |

| Threatened species | ||||

| Adoxaceae | Viburnum microcarpum Schltdl. & Cham. | 5 | ||

| Adoxaceae | Viburnum tiliifolium (Oerst.) Hemsl. | 2 | ||

| Anacardiaceae | Spondias radlkoferi Donn. Sm. | 19 | ||

| Anacardiaceae | Tapirira mexicana Marchand | 12 | ||

| Araliaceae | Oreopanax capitatus (Jacq.) Decne. & Planch. | 4 | ||

| Araliaceae | Oreopanax echinops Decne. & Planch. | 4 | V | |

| Araliaceae | Oreopanax xalapensis (Kunth) Decne. & Planch. | 1 | SP | |

| Betulaceae | Ostrya virginiana (Mill.) K. Koch, | 9 | ||

| Buxaceae | Buxus moctezumae Eg. Kohler, R. Fernández & Zamudio | 10 | ||

| Betulaceae | Carpinus caroliniana Walter | 8 | T | |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros riojae Gómez Pompa | 6 | P | |

| Ericaceae | Vaccinium leucanthum Schltdl. | 2 | ||

| Fabaceae | Cercis canadensis L. | 1 | ||

| Fabaceae | Cojoba arborea (L.) Britton & Rose | 6 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus candicans Née | 8 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus corrugata Hook. | 9 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus germana Schltdl. & Cham. | 8 | V | |

| Fagaceae | Quercus insignis M. Martens & Galeotti | 17 | E | |

| Fagaceae | Quercus sartorii Liebm. | 8 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus xalapensis Bonpl. | 13 | V | |

| Garryaceae | Garrya laurifolia Hartw. ex Benth. | 1 | ||

| Hamamelidaceae | Matudaea trinervia Lundell | 3 | T | V |

| Icacinaceae | Oecopetalum mexicanum Greenm. & C.H. Thomps. | 4 | ||

| Juglandaceae | Juglans mollis Engelm. | 4 | ||

| Juglandaceae | Juglans pyriformis Liebm. | 3 | T | |

| Lauraceae | Beilschmiedia mexicana (Mez) Kosterm. | 5 | ||

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum effusum (Meisn.) Kosterm. | 25 | ||

| Lauraceae | Licaria capitata (Schltdl. & Cham.) Kosterm. | 4 | ||

| Lauraceae | Litsea glaucescens Kunth | 4 | P | |

| Lauraceae | Nectandra reticulata (Ruiz & Pav.) Mez | 3 | ||

| Lauraceae | Nectandra salicifolia (Kunth) Nees | 35 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea disjuncta Lorea-Hern. | 3 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea helicterifolia (Meisn.) Hemsl. | 23 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea psychotrioides Kunth | 12 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea puberula (Rich.) Nees | 1 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea subalata Lundell | 3 | ||

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | 8 | ||

| Lauraceae | Persea liebmannii Mez | 5 | ||

| Lauraceae | Persea longipes (Schltdl.) Meisn. | 28 | E | |

| Lauraceae | Persea schiedeana Nees | 10 | E | |

| Magnoliaceae | Magnolia dealbata Zucc. | 4 | P | |

| Magnoliaceae | Magnolia mexicana DC. | 3 | T | V |

| Magnoliaceae | Magnolia schiedeana Schltdl. | 2 | T | V |

| Melastomataceae | Conostegia volcanalis Standl. & Steyerm. | 3 | ||

| Myrtaceae | Calyptranthes schlechtendaliana O. Berg | 1 | ||

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia mexicana Steud. | 19 | V | |

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia xalapensis (Kunth) DC. | 1 | ||

| Picramniaceae | Picramnia xalapensis Planch. | 1 | ||

| Pinaceae | Abies hickelii Flous & Gaussen | 2 | P | E |

| Pinaceae | Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham. | 1 | ||

| Pinaceae | Pinus ayacahuite C. Ehrenb. ex Schltdl. | 4 | ||

| Pinaceae | Pinus chiapensis (Martínez) Andresen | 3 | ||

| Platanaceae | Platanus mexicana Moric. | 12 | ||

| Podocarpaceae | Podocarpus matudae Lundell | 5 | SP | V |

| Sabiaceae | Meliosma alba (Schltdl.) Walp. | 1 | ||

| Sapindaceae | Acer skutchii Rehder | 11 | CR | |

| Staphyleaceae | Turpinia insignis (Kunth) Tul. | 25 | ||

| Styracaceae | Styrax glabrescens Benth. | 14 | ||

| Taxaceae | Taxus globosa Schltdl. | 2 | SP | E |

| Ulmaceae | Ulmus mexicana (Liebm.) Planch. | 6 | ||

| Species of Least Concern | ||||

| Betulaceae | Alnus acuminata Kunth | 8 | ||

| Cecropiaceae | Cecropia obtusifolia Bertol. | 1 | ||

| Clethraceae | Clethra mexicana DC. | 8 | ||

| Clusiaceae | Clusia salvinii Donn. Sm. | 1 | ||

| Fabaceae | Inga jinicuil Schltdl. | 3 | ||

| Fabaceae | Inga vera Willd. | 3 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus laurina Bonpl. | 9 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus crassifolia Bonpl. | 3 | ||

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum triplinerve (Ruiz & Pav.) Kosterm. | 7 | ||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea veraguensis (Meisn.) Mez | 9 | ||

| Melastomataceae | Conostegia xalapensis D. Don | 1 | ||

| Meliaceae | Trichilia havanensis Jacq. | 4 | ||

| Myrsinaceae | Ardisia compressa Kunth | 20 | ||

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia capuli Schltdl. | 30 | ||

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia acapulcensis Steud. | 10 | ||

| Oleaceae | Fraxinus uhdei Lingelsh. | 6 | ||

| Pinaceae | Pinus montezumae Lamb. | 1 | ||

| Pinaceae | Pinus patula Schltdl. & Cham. | 3 | ||

| Piperaceae | Piper auritum Kunth | 2 | ||

| Rosaceae | Crataegus mexicana Moc. & Sessé ex DC. | 1 | ||

| Rubiaceae | Palicourea padifolia (Roem. & Schult.) C.M. Taylor & Lorence | 5 | ||

| Salicaceae | Xylosma flexuosa (Kunth) Hemsl. | 2 | ||

| Solanaceae | Cestrum aurantiacum Lindl. | 1 | ||

| Sterculiaceae | Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | 1 | ||

| Ulmaceae | Trema micrantha (L.) Blume | 1 | ||

| Verbenaceae | Citharexylum mocinnoi D. Don | 1 | ||

Discussion

The Francisco Javier Clavijero Botanic Garden (JBC) has the horticultural ability to maintain a living plant collection of a diverse taxonomic and ecological composition, mainly accumulated through wild collections and exchanges with other botanic gardens. Our results showed that the best represented plant groups in our collection are Orchidaceae and Zamiaceae. As a result, JBC has almost 50% of Mexican cloud forest orchids and has the most important Cycad collection in Mexico and perhaps in Latin America (Vovides et al., 2014). Caballero et al. (2012) reported that the Instituto de Biología Botanic Garden (Mexico City, Mexico), The Botanic Garden “Xiitbal Neek” (Yucatán, Mexico) and the JBC were the top three Mexican botanic gardens with most documented species held in their collections (1122, 1037, and 743 species, respectively). These results suggest that the JBC scientific collection constitutes an important reservoir of germplasm for species conservation. Also, this collection fulfills the function of protecting species with some degree of threat in their country of origin as specified under the GSPC. In this sense, Oldfield (2011) highlights the importance of Botanic Gardens in the conservation of plant species and emphasizes the need for spaces that represent their natural habitat. Similarly, Chen et al. (2018) point out the relevance of in situ botanical gardens to promote conservation and restoration initiatives.

The traditional collection role has emphasized taxonomic diversity to serve the classical functions of systematic, ecological research, teaching, and public display. The conservation and scientific utility of the JBC collection is reflected in the exceptional accession data and the description of 24 new plant species. For instance, Ceratozamia alvarezii Pérez-Farr., Vovides Iglesias, a new species from Chiapas, Mexico (Perez-Farrera et al., 1999), Stromanthe popolucana Cast.-Campos, Vovides & Vázq. Torres (Castillo-Campos et al., 1998), and Chusquea enigmatica Ruiz-Sanchez, Mejía-Saulés & Clark (Ruiz-Sanchez et al., 2014) were new species described using plant material from the National Collections of the Botanic Garden.

We assessed progress towards achieving the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, (GSPC) specifically Target 8, which calls for “at least 75% of threatened plant species in ex situ collections, preferably in the country of origin” (Heywood and Iriondo, 2003; Callmander, et al., 2005; Blackmore et al., 2011). Surprisingly, our results showed that, currently, the JBC collection is home to 32% of Mexican plant species assessed as threatened by IUCN; although a representative number, there is potential to hold a greater proportion of threatened species. In a global Botanic Garden assessment, Mounce et al. (2017) revealed that a global network of Botanic Gardens holds 41% of threatened plant species. Despite the good representation of threatened species in the JBC collection, larger conservation-based population samples of specific groups (e.g., cycads and highly threatened cloud forest species) should be maintained ex situ to provide the necessary genetic diversity for viable conservation and restoration programs (Cibrian-Jaramillo et al., 2013; Christe et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2015). These iconic plant groups - cycads and cloud forest species - represent taxonomic and regional priorities for the JBC conservation program. In order to capture a high proportion of genetic diversity of these imperiled species in our ex situ collection, we will implement seed banking using conventional freezer conditions recommended by the FAO (FAO, 2014; O’Donnell and Sharrock, 2017; Walters and Pence, 2020).

To advance towards an effective accomplishment of the GSPC and the Mexican Strategy for Plant Conservation, the JBC was recently supported by The National Council on Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACYT) to create a new Ethnobiology display area. This new display area will exhibit a collection of species used in traditional medicine and local culinary plants from central Veracruz. Also, this space will contribute to the rescue of traditional, indigenous, rural, and urban knowledge associated with regional edible plants, bamboos (used in construction and handicraft production), cycads that reach high prices in the ornamental market, and products derived from the hives of native bees, widely valued in traditional medicine and as nutritional supplements.

In summary, the JBC has a unique opportunity to contribute to the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation and the Mexican Strategy for Plant Conservation. It is a center for a valuable and distinctive range of staff skills, including the capacity to engage and educate the public, it is well networked among Mexican Botanic Gardens and with other conservation organizations.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)