Introduction

As pointed out by Endress et al. (2000) the backbone of plant systematics is the comparative study of plant structure, morphology and anatomy. The information obtained through comparative morpho-anatomical studies is necessary for ecological, phylogenetic and evolutionary studies. For example, anatomical characters, especially of leaves, have been extensively used in the systematics of several plant families, including Bromeliaceae (De Faria et al., 2012), Myrtaceae (Al-Edany and Al-Saadi, 2012), Amaryllidaceae (Lin and Tan, 2015), Malpighiaceae (Araújo et al., 2010) and Asteraceae (Castro et al., 1997; Milan et al., 2006; Adedeji and Jewoola, 2008; Bombo et al., 2012; Akinnubi et al., 2014; Rojas-Leal et al., 2017; Lusa et al., 2018). Particularly in Asteraceae, leaf architecture and anatomical characters are extremely diverse (Bombo et al., 2012; Rojas-Leal et al., 2014, 2018) and have been studied from an ecological (Bercu et al., 2012; Moroney et al., 2013; Rivera et al., 2017; Ferraro and Scremin-Dias, 2018), physiological (Bondarev et al., 2003; McKown and Dengler, 2007; Santiago and Kim, 2009), and medical perspective (Cambi et al., 2006; Hulley et al., 2010; García-Sánchez et al., 2012).

Asteraceae is one of the largest families of angiosperms. While cosmopolitan, it is usually dominant in arid and temperate vegetation. Evidence suggests that North America, particularly Mexico, has been important for diversification in some of the most diverse lineages of the family (Noyes and Rieseberg, 1999; Suárez-Mota and Villaseñor, 2011; Villaseñor, 2018). Leaf diversity in the family has been associated to variable environmental conditions such as drought (Ferraro and Scremin-Dias, 2018), saline soils (Grigore and Toma, 2006; Bercu et al., 2012) and light conditions (Rossatto and Kolb, 2010). However, the environment alone does not explain the variation in leaf anatomical characters, because some of these as well as most leaf architectural characters can be constrained by the phylogenetic history, the growth form or the ploidy level of the species (Rivera et al., 2017).

In this paper, we describe the leaf architecture and anatomy of 61 species belonging to 13 tribes of the Asteraceae growing in a xerophytic scrub natural reserve within the central campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. This area represents the remnants of the native flora of Mexico City before the extensive urbanization and it is one of the best-studied protected areas in Mexico in terms of its biodiversity (Lot and Cano-Santana, 2009, Céspedes et al., 2018). The aims of this work are to present a detailed description of the diversity in the leaf architecture and anatomy of Asteraceae occurring in a xerophytic scrub and to discuss characters common to the tribes present.

Materials and Methods

Site description

Plant samples were collected in the “Reserva Ecológica del Pedregal de San Ángel” (REPSA). The REPSA is located in southwestern Mexico City, between coordinates 19°18'21" - 19°20'11"N, 99°10'15" - 99°12'4"W and from 2200 to 2310 m a.s.l. The REPSA has a total area of 237.3 hm (UNAM, 2006). The average annual temperature is 15.6 °C and the total annual rainfall 833 mm. The climate type in the area is temperate subhumid (Cb(w1)w), with a distinctive rain season from June to October and a dry season from November to May. The substratum is volcanic rock from the Xitle volcano eruption, and the soil is scarce and shallow.

Sampling

Samples of mature and healthy leaves of 61 species were collected from August 2008 to December 2009, during two rainy seasons. Leaves were fixed with a formaldehyde-glacial acetic acid-ethyl alcohol solution (Ruzin, 1999) for 24 hours; then rinsed with tap water and stored in a glycerin-ethyl-alcohol-water solution (GAA 1:1:1) until sectioning. All the leaves were scanned with an HP Photosmart Plus scanner (Hewlett-Packard Development Company, Palo Alto, USA), with the highest resolution (2400 dpi) before sectioning. Leaf area was determined using an image analyzer according to the procedure described by Garnier et al. (2001). At least three leaves per species where cleared following Martínez-Cabrera et al. (2007). Three to six leaves per species were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ter-butanol (10-100%) with an automatic tissue processor (TP1020 Leica, Westlar, Germany) remaining for 24 hours in each concentration. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and transverse and paradermal sections of 10 to 12 µm in thickness were cut with a rotatory microtome (RM2125 Leica, Westlar, Germany). The sections were stained with safranin-fast green (Ruzin, 1999) and mounted on synthetic resin. Photographs and measurements were obtained through a microscope (BX51 Olympus, Tokio, Japan) attached to an image analyzer (Image Pro, 2019).

Descriptions were made from cleared leaves and transverse and paradermal sections of three leaves per species. Voucher specimens are at the Herbario Nacional de México (MEXU) of the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Details of the voucher specimens as collector and collection number are given in Appendix. Leaf architecture follows Ellis et al. (2009). Leaf lamina and midvein descriptions follow Metcalfe and Chalk (1979), Dickison (2000) and Koch et al. (2009). Quantitative characters for each species are available in Rivera et al. (2017) and tribe classification follows Anderberg et al. (2007).

Results

The leaf architecture and foliar anatomy are summarized and illustrated (Figs. 1-15) by tribe. When te taxon name is given for a character state meas that the character state occurs only it.

Figure 1: Leaf morphology. A. Cotula australis (Sieber ex Spreng.) Hook. f.; B. Baccharis pteronioides DC.; C. Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell.; D. Helminthotheca echioides (L.) Holub.; E. Sonchus oleraceus L.; F. Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg.; G. Bidens pilosa L.; H. Dahlia coccinea Cav.; I. Piqueria trinervia Cav.; J. Pseudognaphalium viscosum (Kunth) Anderb.; K. Ambrosia cumanensis Kunth; L. Montanoa tomentosa Cerv.; M. Tithonia tubiformis (Jacq.) Cass.; N. Galinsoga parviflora Cav.; O. Barkleyanthus salicifolius (Kunth) H. Rob. & Brettell; P. Pittocaulon praecox (Cav.) H. Rob. & Brettell; Q. Dyssodia papposa (Vent.) Hitchc.; R. Tagetes micrantha Cav. Scale is 0.5 cm in A, C; 1 cm in B, D-R.

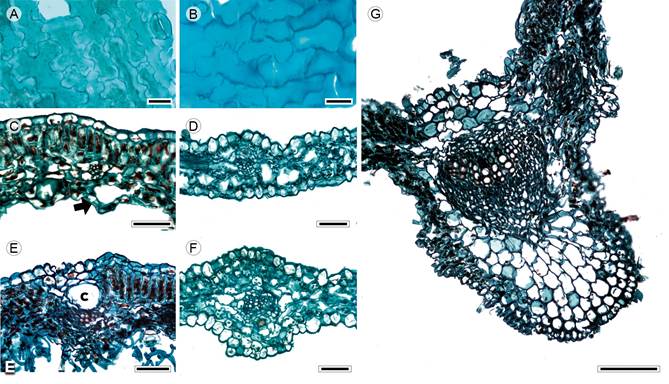

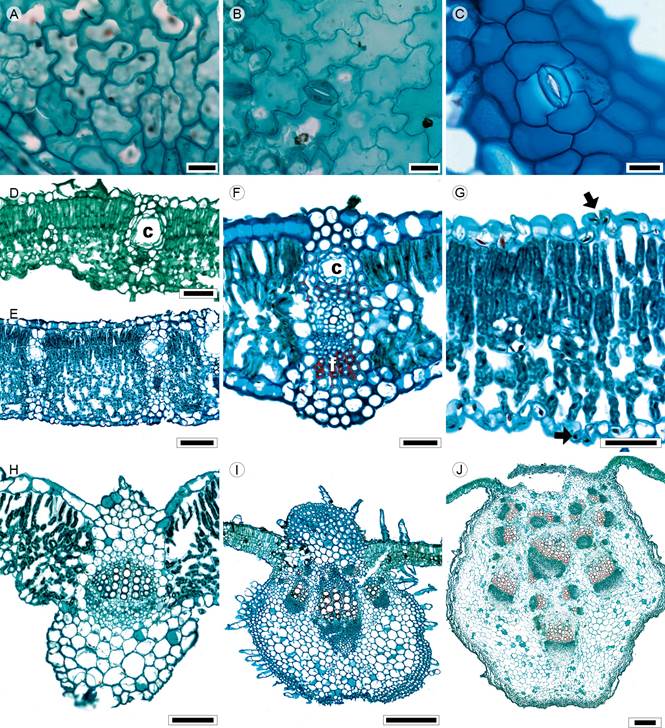

Figure 2: Lamina and midvein in Anthemideae. A, D, F. Cotula australis (Sieber ex Spreng.) Hook. f.; B, C, E, G. Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. Scale is 20 µm in A, B; 50 µm in C-F, 100 µm in G. c=canal.

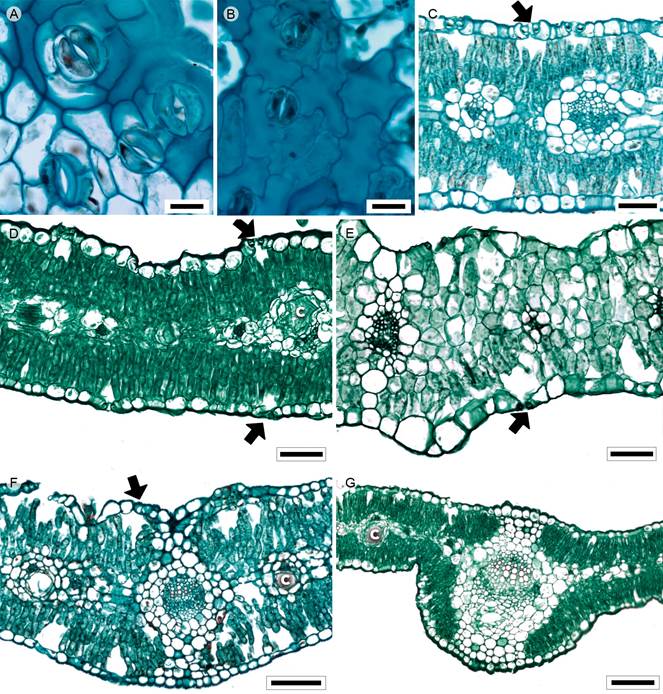

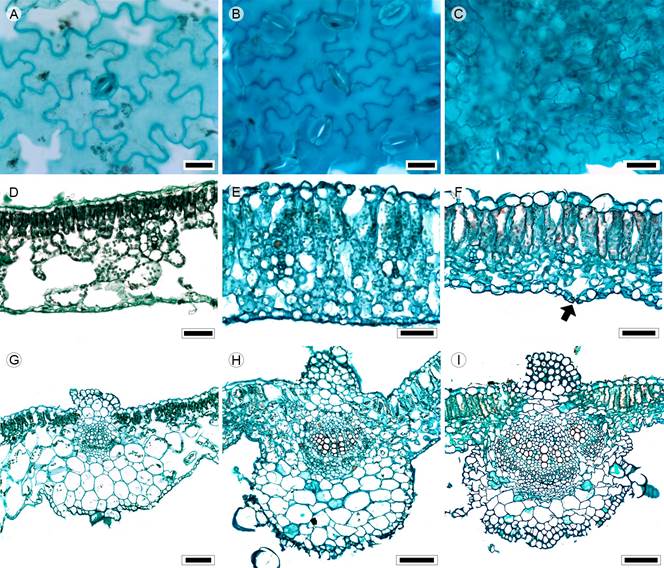

Figure 3: Lamina and midvein in Astereae. A, C. Baccharis salicifolia (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers.; B. Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronquist; D, G. Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist; E. Laennecia sophiifolia (Kunth) G.L. Nesom; F. Baccharis pteronioides DC. Scale is 20 µm in A, B; 50 µm in C-E, 100 µm in F, G. c=canal.

Figure 4: Cleared leaves. A. Florestina pedata (Cav.) Cass.; B. Bidens odorata Cav.; C. Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.; D. Heterosperma pinnatum Cav.; E. Brickellia secundiflora (Lag.) A. Gray; F. Fleischmannia pycnocephala (Less.) R.M. King & H. Rob.; G. Stevia micrantha Lag.; H. Zinnia peruviana (L.) L.; I. Galinsoga parviflora Cav.; J. Pectis prostrata Cav.; K. Tagetes micrantha Cav. Scale is 2 mm in A-D, G, H, J; 1 cm in E, F; 5 mm in I, 21 mm in K.

Figure 5: Lamina and midvein in Bahieae. A, C, E. Florestina pedata (Cav.) Cass.; B, D. Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell. Scale is 20 µm in A, B; 100 µm in C-E.

Figure 6: Lamina and midvein in Cardueae. A-D. Cirsium vulgare (Savi) Ten. Scale is 20 µm in A; 100 µm in B, C; 300 µm in D.

Figure 7: Lamina and midvein in Cichorieae. A, D. Sonchus oleraceus L.; B, E, H. Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg., C. Lactuca serriola L.; F, G. Helminthotheca echioide (L.) Holub. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D, E, 100 µm in F, G; 300 µm in H.

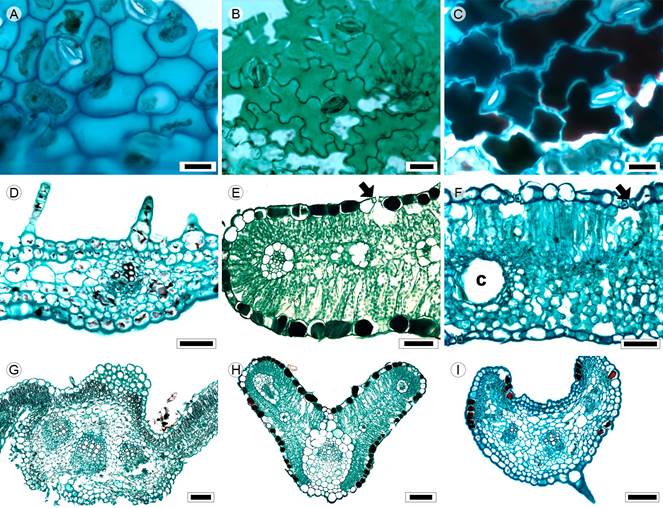

Figure 8: Lamina and midvein in Coreopsideae. A, F. Dahlia coccinea Cav.; B. Bidens odorata Cav.; C, E, G. Cosmos parviflorus (Jacq.) Pers.; D, I. Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.; H. Cosmos parviflorus (Jacq.) Pers. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D-F, 100 µm in G-I. c=canal.

Figure 9: Lamina and midvein in Eupatorieae. A, K. Stevia origanoides Kunth; B. Stevia salicifolia Cav.; C, D. Stevia tomentosa Kunth, E. Brickellia veronicifolia (Kunth) A. Gray; F. Fleischmannia pycnocephala (Less.) R.M. King & H. Rob.; G. Ageratina deltoidea (Jacq.) R.M. King & H. Rob.; H. Piqueria trinervia Cav.; I. Brickellia secundiflora (Lag.) A. Gray; J. Ageratina choricephala (B.L. Rob.) R.M. King & H. Rob. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D-F, 100 µm in H-K; 300 µm in G.

Figure 10: Lamina and midvein in Gnaphalieae. A, D, F. Pseudognaphalium canescens (DC.) Anderb.;, E, G. Pseudognaphalium semilanatum (DC.) Anderb.; C, H. Pseudognaphalium viscosum (Kunth) Anderb. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D, E, 100 µm in F-H.

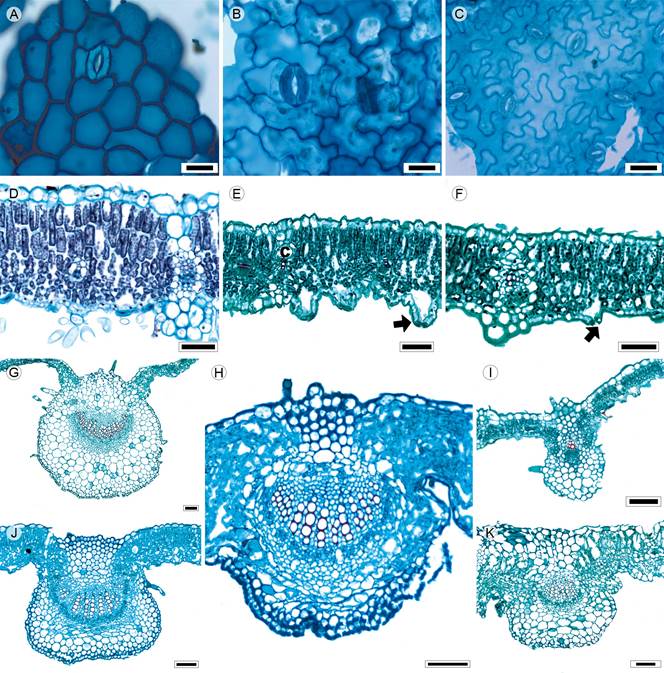

Figure 11: Lamina and midvein in Heliantheae. A, D. Montanoa tomentosa Cerv., B, J. Montanoa grandiflora Alamán ex DC.; C, F. Lagascea rigida (Cav.) Stuessy, E. Verbesina virgata Cav.; G. Ambrosia cumanensis Kunth, H. Zinnia peruviana (L.) L.; I. Tithonia tubiformis (Jacq.) Cass. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D, F, G, 100 µm in E, H; 300 µm in I, J. c=canal.

Figure 12: Lamina and midvein in Millerieae. A, D, G. Jaegeria hirta (Lag.) Less.; B, E, H. Galinsoga parviflora Cav.; C. Melampodium longifolium Cerv. ex Cav.; F, I. Melampodium perfoliatum (Cav.) Kunth. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D-F, 100 µm in G-I.

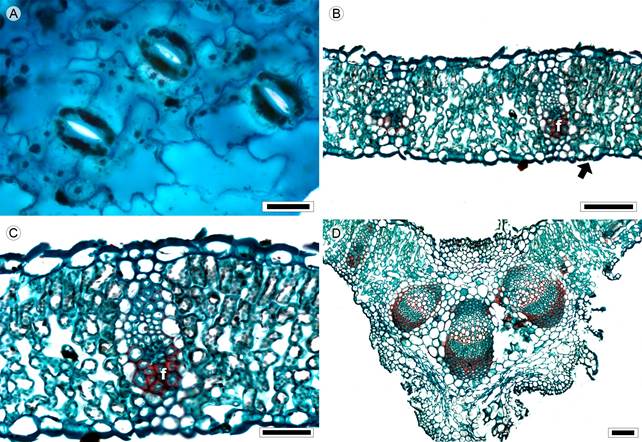

Figure 13: Lamina and midvein in Nassauvieae. A-D. Acourtia cordata (Cerv.) B.L. Turner. Scale is 20 µm in A; 100 µm in B, D; 50 µm in C. f=fibers.

Figure 14: Lamina and midvein in Senecioneae. A, D, G. Barkleyanthus salicifolius (Kunth) H. Rob. & Brettell; B, E, H. Pittocaulon praecox (Cav.) H. Rob. & Brettell; C, F, I. Roldana lobata La Llave. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in E, F; 100 µm in D, G-I; 300 µm in I, J. c=canal.

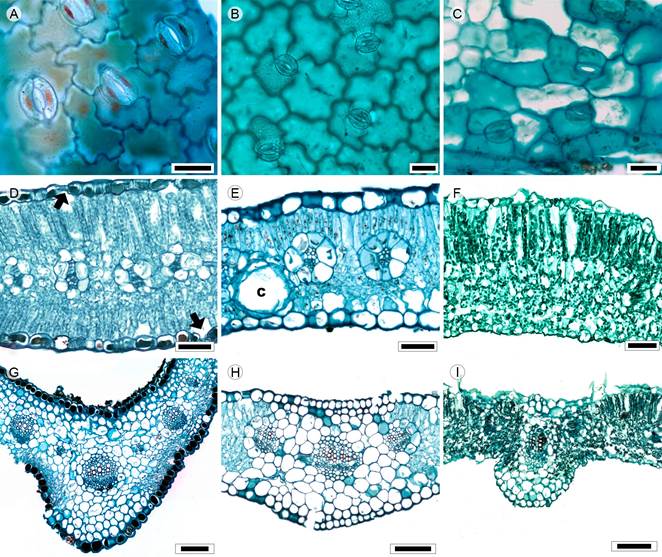

Figure 15: Lamina and midvein in Tageteae. A, D, G. Dyssodia papposa (Vent.) Hitchc.; B, E, H. Pectis prostrata Cav.; C. Tagetes micrantha Cav.; F, I. Tagetes tenuifolia Cav. Scale is 20 µm in A-C; 50 µm in D-F, 100 µm in G-I.

Asteraceae

Tribe Anthemideae

Two species: Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. and Cotula australis (Sieber ex Spreng.) Hook. f. (Figs. 1, 2).

Leaves sessile, alternate, simple (Artemisia L.), pinnatisect or bipinnatisect (Cotula L., Fig. 1A); lamina size microphyll, lamina shape linear to lanceolate, margin entire, revolute (Artemisia), apex acuminate, base truncate (Artemisia) or concave (Cotula); primary vein framework pinnate, primary vein straight or slightly undulate, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate (Artemisia) or lacking (Cotula), veinlets simple, straight, unbranched, marginal ultimate venation looped (Artemisia) or incomplete (Cotula); teeth absent; leaves hypostomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal-elongated with S-undulate anticlines (Figs. 2A, B), adaxial epidermis glabrate, abaxial epidermis subglabrous (Cotula) to tomentose (Artemisia), with multicellular trichomes and anomocytic stomata (Fig. 2A), in transverse view, cuticle striate and thin (<0.44 µm), epidermises uniseriate with conical or rectangular cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, adaxial epidermis thicker than the abaxial (Artemisia) or both epidermises equally thick (Cotula), stomata at the same level as the epidermal cells (Cotula) or above (Artemisia); mesophyll homogenous or heterogeneous (Figs. 2C, D), palisade parenchyma generally occupying 50% of the mesophyll (Artemisia, Fig. 2C); vascular bundles collateral with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, canals associated with vascular bundles (Fig. 2E); midvein contour gently protruded in both surfaces (Fig. 2F) or flat adaxially and projected abaxially (Fig. 2G), cuticle conspicuously striate and thicker than in the lamina, epidermises uniseriate with narrow convex cells and thicker outer periclinal and anticlinal walls, beneath the epidermis, annular collenchyma and towards the vascular bundle parenchyma, a single central collateral vascular bundle, within the bundle, xylem with radial rows of three to five vessels, phloem formed by three to five rows of cells, a cap of sclereids (three to four layers) external to xylem.

Tribe Astereae

Six species: Baccharis pteronioides DC., B. salicifolia (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers., Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronquist, C. canadensis (L.) Cronquist, C. coronopifolia Kunth and Laennecia sophiifolia (Kunth) G.L. Nesom (Figs. 1, 3).

Leaves sessile or petiolate, alternate, simple (Fig. 1B) or pinnately lobed (Laennecia Cass., C. coronopifolia); lamina size microphyll to notophyll, lamina shape linear-lanceolate to linear-oblong, margin entire (C. bonariensis, Laennecia), dentate to serrate (Baccharis L., C. canadensis, C. coronopifolia), margin revolute (C. bonariensis), apex acuminate to convex, base cuneate (Baccharis), truncate or lobate (C. bonariensis, C. canadensis, Laennecia) to cordate (C. coronopifolia); primary vein framework pinnate (B. salicifolia, Laennecia) or palmate (B. pteronioides, Conyza Less.), primary vein straight, secondary venation brochidodromous or actinodromous (B. pteronioides, Conyza), areole development moderate, veinlets simple, curved, unbranched or one-branched (C. coronopifolia), marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth lacking principal vein, with accessory vein straight (Baccharis, Conyza) or absent (Laennecia); leaves amphistomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal or polygonal-elongated with straight anticlines (Baccharis, Fig. 3A, C. canadensis) or tetragonal to tetragonal-elongated with S-undulated to V-undulated anticlines (C. bonariensis, C. coronopifolia, Fig. 3B, Laennecia), adaxial and abaxial surfaces pubescent, with multicellular trichomes and glands and anomocytic or cyclocytic stomata (Baccharis, Fig. 3A), in transverse view, cuticle conspicuously striate and thickness between 0.28 and 0.57 µm, epidermises uniseriate with square or cupola cells (Figs. 3C-E) and thicker outer periclinal walls, both epidermis with the same width, stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Figs. 3C, D) or homogeneous (Laennecia, Fig. 3E), palisade parenchyma occupying 33 to 41% of the mesophyll, except for Laennecia, paraveinal mesophyll between the vascular bundles; collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, extensions of the sheath (girders) (Fig. 3E), except in C. bonariensis and C. canadensis, girders across the leaf (C. coronopifolia, Laennecia) or linked to either adaxial or abaxial surface (Baccharis), canals generally associated with vascular bundles (Fig. 3D); midvein contour with a slight central depression adaxially and flat abaxially (Fig. 3F) or flat adaxially and round and protruding abaxially (Fig. 3G), cuticle thicker than in the lamina, epidermises uniseriate with narrow convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, annular collenchyma below the epidermises mostly in the central region of the midrib (Baccharis) and parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, with palisade parenchyma towards the center of the midvein, a single central collateral vascular bundle (Figs. 3F, G) or three bundles, within the bundle, xylem with radial rows of two to six vessels separated by one or two rows of parenchyma, phloem formed by three to five rows of cells, a cap of sclereids associated with phloem and xylem, more conspicuous in the larger bundle.

Tribe Bahieae

Two species: Florestina pedata (Cav.) Cass. and Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell. (Figs. 1, 4, 5).

Leaves petiolate, opposite at the base and alternate near the apex, pinnatisect or bipinnatisect (Schkuhria Roth, Fig. 1C) or palmatisect (Florestina Cass.); lamina size microphyll, lamina shape linear (Schkuhria) or elliptic (Florestina), margin entire, apex straight, base concave or cuneate; primary vein framework pinnate (Fig. 4A), primary vein undulate (Florestina), weak, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate, veinlets simple, straight, unbranched (Florestina) or absent (Schkuhria), marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth absent; leaves amphistomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal or polygonal elongated with S-undulated and U-undulated anticlines (Figs. 5A, B), both surfaces subglabrous, with short glandular trichomes and anomocytic stomata (Florestina, Schkuhria) or anisocytic (Schkuhria), in transverse view, cuticle striate with a thickness between 0.33 to 0.38 µm, epidermises uniseriate, with rectangular to hemispherical cells and thicker outer periclinal walls (Figs. 5C, D), adaxial epidermis wider than abaxial (Florestina) or both epidermis the same width (Schkuhria), stomata at the same level as the epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Florestina, Fig. 5C) or homogeneous (Schkuhria, Fig. 5D), palisade parenchyma occupying 54% of the leaf in Florestina; collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, sheath extensions rare (Fig. 5C), canals associated with vascular bundles; midvein contour with a slight central depression adaxially and flat abaxially in Schkuhria (Fig. 5D), round and slightly projected adaxially and round and protruding abaxially in Florestina (Fig. 5E), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate, with cupola cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermises, four rows of annular collenchyma (Schkuhria) or two to four rows of angular collenchyma (Florestina) and parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, with palisade one third towards the abaxial surface, a single central collateral vascular bundle (Fig. 5E) or two bundles, within the bundle, xylem with radial rows of three to four vessels separated by one or two rows of parenchyma, phloem formed by three to five rows of cells, caps of sclereids with thin walls associated to xylem and phloem.

Tribe Cardueae

One species: Cirsium vulgare (Savi) Ten. (Fig. 6).

Leaves sessile, alternate, pinnately lobed; lamina size mesophyll, lamina shape triangular, margin toothed and ending in spines, apex acuminate and base cordate to amplexicaul; primary vein framework pinnate, primary vein straight, prominent, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate, veinlets simple, curved, unbranched, marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth lacking principal vein, with accessory vein straight, spinose; leaves amphistomatic; in surface view, cells elongated polygonal with straight anticlines (Fig. 6A), abaxial and adaxial surfaces pubescent, with multicellular trichomes and stiff hairs stomata anomocytic or anisocytic in the same plant, in transverse view, cuticle striate and 0.3 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with rectangular cells and thicker cells and outer periclinal walls, adaxial epidermis wider than abaxial epidermis, stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous with two or three rows of palisade parenchyma (Fig. 6B), occupying 54% of the mesophyll; collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, girders seldom in secondary veins, with some lignified cells (Fig. 6C), canals absent; midvein contour protruded adaxially and sharply projected abaxially triangular (Fig. 6D), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate, with squared cells, immediately beneath the abaxial epidermis annular collenchyma (1-3 layers) and abundant parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, no palisade in the midvein, five to six collateral vascular bundles, the smaller ones towards the adaxial surface (Fig. 6D), within the bundles, xylem in clusters of two to nine vessels or radial rows of three to five vessels and parenchyma, phloem abundant and formed by five to seven rows of cells, caps of sclereids wide (10-12 layers) on each side of the vascular tissue.

Tribe Cichorieae

Four species: Helminthotheca echioides (L.) Holub, Lactuca serriola L., Sonchus oleraceus L. and Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg. (Figs. 1, 7).

Leaves sessile, although at the lamina base narrow looking like a petiole, leaves opposite or alternate, simple (Helminthotheca Vaill., Lactuca L., Fig. 1D) to pinnately lobed (Sonchus L., Taraxacum F.H. Wigg., Figs. 1E, F); lamina size mesophyll to macrophyll, lamina shape variable, generally elliptic to obovate, margin dentate or serrate, frequently combining both characteristics, edge of the leaf blade appear sinuous (Helminthotheca), apex straight, base truncate or lobate to cordate; primary vein framework pinnate or palmate (Sonchus), primary vein straight, prominent, secondary venation brochidodromous (Helminthotheca, Lactuca, Taraxacum) or basal actinodromous (Sonchus), areole development moderate, veinlets simple, straight (Lactuca, Taraxacum) or once-branched (Helminthotheca, Sonchus), marginal ultimate venation looped (Lactuca, Sonchus, Taraxacum) or incomplete (Helminthotheca); teeth principal vein terminating in a tooth apex (Helminthotheca, Taraxacum) or accessory veins straight (Sonchus); leaves amphistomatic or hypostomatic (Sonchus); in surface view, cells tetragonal or tetragonal elongated with S-undulate or U-undulate anticlines (Figs. 7A-C), both surfaces glabrous (Sonchus, Taraxacum) or bristly and glandular (Helminthotheca) and anomocytic stomata, in transverse view, cuticle smooth and thickness between 0.31 and 0.45 µm, epidermises uniseriate, with conical cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, adaxial epidermis wider than the abaxial (Sonchus, Taraxacum), stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Helminthotheca, Sonchus, Figs. 7D, E) or homogeneous (Lactuca, Taraxacum, Fig. 7F), palisade occupying 36 to 46% of the mesophyll, collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath (Figs. 7D-F), girders present in all species and running across the mesophyll, canals absent; midvein contour ample flat adaxially and round sharply projected abaxially (Fig. 7G) or protruded in both surfaces with a large lysogenic area in Taraxacum (Fig. 7H), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate, with squared cells, immediately below a hypodermis (single layer) and parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, with palisade parenchyma abaxially in Taraxacum, three to five collateral vascular bundles, within the bundles, xylem in radial rows of three to eight vessels separated by one or two rows of parenchyma, phloem formed by five to ten rows of cells, caps of sclereids (four to six layers) associated with xylem and phloem.

Tribe Coreopsideae

Six species: Bidens odorata Cav., B. pilosa L., Cosmos bipinnatus Cav., C. parviflorus (Jacq.) Pers., Dahlia coccinea Cav. and Heterosperma pinnatum Cav. (Figs. 1, 4, 8).

Leaves petiolate, rarely sessile (C. bipinnatus), opposite, generally pinnatisect or bipinnatisect; lamina size microphyll to mesophyll, lamina shape linear (Cosmos Cav., Heterosperma Cav.) or ovate to elliptic (Bidens L., Dahlia Cav., Figs. 1G, H), margin serrate (Bidens, Dahlia) or entire (Cosmos, Heterosperma), apex acuminate or straight, base truncate or concave; primary vein framework pinnate (Figs. 4B-D), primary vein straight or undulate (Heterosperma), prominent or weak (Heterosperma), secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate (Bidens, Dahlia), poor (Cosmos) or lacking (Heterosperma), veinlets simple, curved (Bidens, Heterosperma), straight (C. bipinnatus) or once branched (C. parviflorus, Dahlia), marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth with principal vein and two accessory veins straight (Bidens), accessory veins convex (Dahlia) or absent (Cosmos, Heterosperma); leaves amphistomatic, in surface view, cells tetragonal elongated or polygonal elongated with straight (Dahlia) or S-undulated to U-undulated anticlines (Figs. 8A-C), both epidermises glabrous or glabrate (Cosmos, Heterosperma), with multicellular trichomes and glands (Bidens, Dahlia) and stomata anomocytic or anisocytic (Dahlia, Heterosperma), in transverse view, cuticle striate in all species except C. parviflorus and thickness between 0.23 and 0.42 µm, epidermises uniseriate, with cupola or conical cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, tannins occluding cell lumina in Cosmos (Fig. 8E), stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll homogeneous in C. bipinnatus (Fig. 8D) and heterogeneous in C. parviflorus (Fig. 8E) and the rest of the species (Fig. 8F), palisade occupying 41 to 53% of the mesophyll; collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath (Figs. 8E, F), girders in Dahlia and Heterosperma, canals associated with vascular bundles or in the mesophyll (Fig. 8F); midvein contour projection on the adaxial surface and round and slightly protruding on the abaxial (Bidens, Dahlia, Fig. 8G) or convex adaxially and round abaxially (Cosmos, HeterospermaFigs. 8H, I), cuticle similar to lamina. epidermises uniseriate, with convex cells and thick-walled cells, below the adaxial epidermis one-three layers of annular collenchyma and palisade parenchyma and abaxially two layers of angular collenchyma, vascular tissue surrounded by parenchyma or a sheath (Fig. 8H), a single central collateral vascular bundle (Cosmos, Heterosperma) or three bundles (Bidens, Dahlia, Fig. 8G), within the bundles, xylem in radial rows of three to five vessels, phloem formed by three to five rows of cells, a cap of sclereids (three to four layers) external to xylem in Bidens.

Tribe Eupatorieae

Fourteen species: Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) R.M. King & H. Rob., A. choricephala (B.L. Rob.) R.M. King & H. Rob., A. cylindrica (McVaugh) R.M. King & H. Rob., A. deltoidea (Jacq.) R.M. King & H. Rob., Brickellia secundiflora (Lag.) A. Gray, B. veronicifolia (Kunth) A. Gray, Chromolaena pulchella (Kunth) R.M. King & H. Rob., Fleischmannia pycnocephala (Less.) R.M. King & H. Rob., Piqueria trinervia Cav., Stevia micrantha Lag., S. origanoides Kunth, S. salicifolia Cav., S. subpubescens Lag. and S. tomentosa Kunth (Figs. 1, 4, 9).

Leaves petiolate rarely sessile (S. salicifolia), opposite, simple (Fig. 1I); lamina size variable from microphyll (B. veronicifolia) to macrophyll (A. deltoidea), lamina shape ovate to elliptic, linear (S. salicifolia) or triangular (A. deltoidea), margin crenate to serrate, sometimes both (Stevia Cav.), apex straight to rounded, base highly variable: truncate, concave, concavo-convex, cuneate or cordate; primary vein framework pinnate or palmate, primary vein straight, prominent or weak (Ageratina Spach, Stevia), secondary venation brochidodromous or actinodromous basal (Fleischmannia Sch. Bip., Stevia, Figs. 4F, G), areole development moderate or poor (Brickellia Elliott), veinlets simple, curved, linear (Ageratina) or once-branched (Chromolaena DC., S. tomentosa), marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth with accessory veins and simple or lacking teeth (Chromolaena); leaves hypostomatic in most species, just four species amphistomatic (A. cylindrica, P. trinervia, S. origanoides, S. salicifolia); in surface view, cells tetragonal-elongated or polygonal with straight, V-undulated, U-undulated or S-undulated anticlines (Figs. 9A-C), both surfaces tomentose, rarely glabrous (Piqueria), with multicellular trichomes and stomata anomocytic, anisocytic (S. origanoides) or staurocytic (A. cylindrica, P. trinervia, S. salicifolia); in transversal view, cuticle striate and 0.21 to 0.60 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with rectangular or convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls (Figs. 9D-F), adaxial epidermis sometimes wider than the abaxial (A. cylindrica, A. deltoidea, Brickellia, Chromolaena, Fleischmannia, Stevia), stomata at the same level or above the epidermal cells (A. deltoidea, Brickellia, C. pulchella, Fleischmannia, S. micrantha, S. origanoides, Figs. 9E, F); mesophyll heterogeneous (Figs. 9D-F), except in Piqueria, homogeneous, palisade occupying 45 to 56% of the mesophyll, collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath or sclerenchyma (S. salicifolia), girders in secondary veins (Fig. 9F), canals associated with vascular bundles or in the mesophyll; midvein contour flat or slightly projected adaxially and abaxially round or square protruded or highly protruded (Figs. 9G-K), cuticle conspicuously striate, epidermises uniseriate, with square and convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, below both epidermises, angular collenchyma (1 to 3 layers) limited by the mesophyll (Piqueria) or exclusively parenchyma (Fig. 9K), a central collateral vascular bundle forming an open arc, within the bundle, xylem in clusters of three to ten vessels or radial rows of three to five vessels separated by radial rows of parenchyma, phloem formed by one to five rows of cells, caps of parenchyma or sclerenchyma (three to seven layers) associated to xylem and phloem (Fig. 9H).

Tribe Gnaphalieae

Three species: Pseudognaphalium canescens (DC.) Anderb., P. semilanatum (DC.) Anderb. and P. viscosum (Kunth) Anderb. (Figs. 1, 10).

Leaves sessile, alternate, simple (Fig. 1J); lamina size microphyll, lamina shape elliptic to oblong, margin entire, revolute (P. viscosum), apex straight to acuminate, base truncate, sometimes cordate to sagittate (P. viscosum); primary vein framework pinnate, primary vein straight, weak, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate, veinlets simple, curved, marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth absent; leaves hypostomatic (P. canescens, P. semilanatum) or amphistomatic (P. viscosum); in surface view, cells tetragonal or elongated tetragonal with U-undulated to V-undulated anticlines (Figs. 10A-C), adaxial surface hirsute, abaxially densely tomentose, with glandular trichomes and anomocytic stomata, in transverse view, cuticle apparently smooth and between 0.20 and 0.42 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with rectangular and conical cells (Figs. 10D, E), adaxial epidermis wider than abaxial, stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous with one to two rows of palisade parenchyma, palisade occupying 41 to 46% of the mesophyll; vascular bundles collateral with a parenchymatous bundle sheath in P. canescens and P. semilanatum, with girders (Figs. 10D, E), canals absent; midvein contour flat or slightly convex adaxially and abaxially round and protruded (Figs. 10F-H), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate with convex cells and thick outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the abaxial epidermis a layer of angular collenchyma and mesophyll extending to most of the abaxial faces, abundant parenchyma surrounding the vascular tissue, a single central collateral vascular bundle, within the bundle, xylem in radial rows of two to five vessels, phloem formed by three to four rows of cells, a cap of parenchyma (two or three layers) associated with phloem.

Tribe Heliantheae

Eleven species: Acmella repens (Walter) Rich., Aldama buddleiiformis (DC.) E.E. Schill. & Panero, A. excelsa (Willd.) E.E. Schill. & Panero, Ambrosia cumanensis Kunth, Lagascea rigida (Cav.) Stuessy, Montanoa grandiflora Alamán ex DC., M. tomentosa Cerv., Simsia amplexicaulis (Cav.) Pers., Tithonia tubiformis (Jacq.) Cass., Verbesina virgata Cav. and Zinnia peruviana (L.) L. (Figs. 1, 4, 11).

Leaves petiolate or sessile, opposite, sometimes alternate near the apex, simple or pinnately lobed (Ambrosia L., Fig. 1K; M. grandiflora, Simsia Pers.); lamina size microphyll to megaphyll, lamina shape ovate to elliptic, margin entire (Acmella Rich. ex Pers., Aldama La Llave, Zinnia L.), crenate to serrate (M. grandiflora), dentate (V. virgata) and erose (Simsia), apex straight to acuminate, base truncate, concave, cuneate or cordate (Figs. 1L, M); primary vein framework pinnate or palmate, primary vein straight (Fig. 4H), prominent (Lagascea Cav.), secondary venation brochidodromous or actinodromous basal (Aldama, M. tomentosa, Tithonia Desf. ex Juss., Zinnia, Fig. 4H), areole development moderate or good (Lagascea), veinlets oncebranched (Acmella, M. tomentosa), simple, straight (Aldama, Ambrosia, Lagascea, Tithonia, Zinnia) or simple curved in the other taxa, marginal ultimate venation looped or incomplete (Simsia, Verbesina L.); teeth with primary and accessory veins straight (Ambrosia), only accessory veins curved (Acmella, Simsia, Tithonia, Verbesina) or absent (Aldama, Lagascea, Zinnia); leaves amphistomatic, rarely hypostomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal, tetragonal-elongated or polygonal with straight to S-undulate anticlines (Figs. 11A-C), both epidermises hispid to tomentose, with glands and unicellular or multicellular trichomes and stomata anomocytic, anisocytic or staurocytic (Lagascea), in transverse view, cuticle striate and between 0.21 and 1.15 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with cupola or rectangular cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, adaxial epidermis is wider than abaxial in most species or both are equally wide (Acmella, Lagascea, Verbesina), stomata at the same level as other epidermal cells or above (Fig. 11G); mesophyll heterogeneous (Figs. 11D-G), palisade occupying from 32 to 100% of the mesophyll (Aldama, Lagascea, Simsia); collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, girders of parenchyma (Figs. 11D, E) or sclerenchyma (Aldama, Lagascea, Fig. 11F), secondary veins with angular collenchyma toward both surfaces, canals associated with vascular bundles; midvein contour flat or protruded on the adaxial surface and abaxially round and protruding (Figs. 11H-J) or a crest toward both surfaces (Ambrosia, Fig. 11G), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate with cupola cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermises, parenchyma (Fig. 11H) or annular or angular collenchyma, frequently continuous (four to five layers, Figs. 11I, J) or discontinuous xylem in radial rows of two to ten vessels or in clusters of (two to five layers), mesophyll or parenchyma towards the three to fifteen or more vessels, phloem formed by five to vascular tissue, a single central collateral vascular bundle ten rows of cells, caps of parenchyma (Simsia, Zinnia) or or more than ten bundles (Figs. 11H-J), within the bundles, sclerenchyma associated with xylem and phloem.

Tribe Millerieae

Four species: Galinsoga parviflora Cav., Jaegeria hirta (Lag.) Less., Melampodium longifolium Cerv. ex Cav. and M. perfoliatum (Cav.) Kunth (Figs. 1, 4, 12).

Leaves sessile (Jaegeria Kunth) or petiolate (Galinsoga Ruiz & Pav., Melampodium L.), opposite and simple; lamina size notophyll to mesophyll, lamina shape elliptic, obovate or ovate, margin crenate to serrate (Fig. 1N), apex acuminate to straight, base cuneate to rounded, sometimes concave (Galinsoga) or sagittate (Melampodium); primary vein framework palmate (Fig. 4I), primary veins straight, prominent, secondary venation actinodromous basal, areole development moderate, veinlets simple, curved (Galinsoga), straight (Jaegeria) or once-branched (Melampodium), marginal ultimate venation looped (Jaegeria, Galinsoga) or incomplete (Melampodium), teeth with accessory veins straight; leaves amphistomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal-elongated with S-undulated, U-undulated or V-undulated anticlines (Figs. 12A-C), both epidermis strigose to hirsute, with multicellular trichomes and stomata anomocytic, in transverse view, the cuticle apparently smooth and between 0.23 and 0.24 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with cupola or rectangular cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, adaxial epidermis wider than the abaxial, stomata at the same level as the epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Figs. 12C, D), palisade occupying 25 to 39% of the mesophyll, in Jaegeria most of the mesophyll occupied by aerenchyma (Fig. 12C); collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath and girders (Galinsoga and Melampodium), canals associated with vascular bundles; midvein contour with a projection on the adaxial surface and abaxially wide slightly protruding (Jaegeria) or round and protruding (Figs. 12G-I), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate, rectangular or convex cells with thicker outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermises parenchyma or annular collenchyma, one to three layers, restricted to the projections and parenchyma towards vascular tissue, a central arc of vascular tissue (Figs. 12G, I) and in Galinsoga opposite to the main arc phloem and some vessels evident (Fig. 12H), within the bundle, xylem in radial rows of two to five vessels or clusters of five to ten vessels, phloem formed by one to four rows of cells, caps associated to vascular tissue absent.

Tribe Nassauvieae

One species: Acourtia cordata (Cerv.) B.L. Turner (Fig. 13).

Leaves sessile, alternate and simple; lamina size macrophyll, lamina shape elliptic to oblong, margin dentate, apex convex, base cordate; primary vein framework pinnate, primary vein straight, prominent, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate, veinlets simple, curved, marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth more than one central plus two accessories straight; leaves amphistomatic; in superficial view, cells tetragonal-elongated with S-undulate anticlines (Fig. 13A), both surfaces pubescent, with multicellular trichomes and stomata anomocytic or anisocytic, in transverse view, the cuticle smooth and less than 0.06 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, both epidermis of the same width, stomata at the same level as epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous with one row of palisade parenchyma, occuping 26% of the mesophyll (Fig. 13B); collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous sheath, girders present in secondary veins and usually composed of sclerenchyma associated to phloem (Fig. 13C), canals absent; midvein contour adaxially flat and abaxially protruded triangular (Fig. 13D), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate with narrow convex cells and thick outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermises, angular collenchyma of one or two layers and parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, three collateral vascular bundles, within the bundles, xylem with more than twelve vessels, separated by parenchyma, phloem formed by six to ten rows of cells, caps of abundant sclerenchyma associated with xylem and phloem (Fig. 13D).

Tribe Senecioneae

Three species: Barkleyanthus salicifolius (Kunth) H. Rob. & Brettell, Pittocaulon praecox (Cav.) H. Rob. & Brettell and Roldana lobata La Llave (Figs. 1, 14).

Leaves petiolate, alternate and simple; lamina size mesophyll to macrophyll, lamina shape ovate-elliptic (Pittocaulon H. Rob. & Brettell) or linear-elliptic (Barkleyanthus H. Rob. & Brettell, Roldana La Llave), margin entire, serrate or dentate, apex acuminate acute (Barkleyanthus, Fig. 10; Pittocaulon, Roldana), base lobate (Pittocaulon, Fig. 1P), rounded to truncate (Roldana) or cuneate (Barkleyanthus); primary vein framework pinnate or actinodromous, primary vein straight, prominent, secondary venation is parallelodromous (Barkleyanthus), actinodromous suprabasal (Pittocaulon) or mixed craspedrodromous (Roldana), areole development moderate (Barkleyanthus, Pittocaulon) or good (Roldana), veinlets once-branched (Barkleyanthus, Pittocaulon) or absent (Roldana), marginal ultimate venation looped; teeth with accessory veins (Barkleyanthus, Roldana) or absent (Pittocaulon); leaves amphistomatic or hypostomatic, in surface view, cells polygonal-elongated with straight anticlines (Figs. 14A-C), both epidermises glabrous or glabrate and stomata anomocytic, in transverse view, the cuticle striate and between 0.36 and 0.46 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with rectangular or conical cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, both epidermis equally in width, stomata at the same level as the epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Fig. 14D) or homogeneous (Pittocaulon, Roldana, Figs. 14E, F), palisade occupying 53% of the mesophyll (Barkleyanthus); collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, girders in secondary veins, canals associated with vascular bundles or in the mesophyll (Barkleyanthus); midvein contour slightly convex or protruded adaxially and abaxially round and protruded (Figs. 14G, I) or gently protruded in both surfaces (Fig. 14H), cuticle similar to lamina, epidermises uniseriate with convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermis angular collenchyma, one to three layers surrounding almost all the midrib (Pittocaulon), restricted to a small region in either surface (Barkleyanthus) or lacking (Roldana), a single central collateral vascular bundle or three bundles forming an arc (Fig. 14E), within the bundle, xylem in radial rows of two to ten vessels, phloem formed by two to five rows of cells, cap of sclerenchyma associated with xylem.

Tribe Tageteae

Four species: Dyssodia papposa (Vent.) Hitchc., Pectis prostrata Cav., Tagetes micrantha Cav. and T. tenuifolia Cav. (Figs. 1, 4, 15).

Leaves sessile, opposite, simple (Pectis L.) or pinnatisect (Dyssodia Cav., Tagetes L., Figs. 1Q, R); lamina size nanophyll to mesophyll, lamina shape linear-elliptic to obovate, margin entire (P. prostrata, T. micrantha), toothed (Dyssodia) or serrate (T. tenuifolia), apex straight or acuminate, base cuneate or truncated; primary vein framework pinnate (Figs. 4J, K), primary vein straight, prominent, secondary venation brochidodromous, areole development moderate (T. tenuifolia), poor (Dyssodia, Pectis) or lacking (T. micrantha), veinlets simple, curved (Dyssodia, Tagetes), straight (Pectis) or absent (Pectis), marginal ultimate venation looped (Pectis, Tagetes) or incomplete (Dyssodia); teeth with primary and accessory veins straight, primary vein termination at the apex of tooth; leaves amphistomatic; in surface view, cells tetragonal, tetragonal-elongated or polygonal with straight to S-undulate anticlines (Figs. 15A-C), glabrate in both surfaces and stomata anomocytic or anisocytic, in transverse view, the cuticle striated or smooth and between 0.19 and 0.44 µm in thickness, epidermises uniseriate, with square or convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, both epidermises equall in width, tannins occluding cell lumina in Dyssodia, stomata at the same level as the epidermal cells; mesophyll heterogeneous (Figs. 15D-F), palisade occupying 27 to 42% of the mesophyll; collateral vascular bundles with a parenchymatous bundle sheath, paraveinal mesophyll between vascular bundles (Fig. 15D), canals associated with vascular bundles or in the mesophyll (Fig. 15E); midvein contour adaxially flat and abaxially gently protruded (Pectis, (Fig. 15H, T. micrantha) or adaxially flat and abaxially protruded round (T. tenuifolia) or triangular (Dyssodia) (Figs. 15G, I), cuticle conspicuously striate and thicker than the lamina, epidermises uniseriate with convex cells and thicker outer periclinal walls, immediately beneath the epidermises, a layer of annular collenchyma and parenchyma towards the vascular tissue, a single central collateral vascular bundle or three bundles (Fig. 15H), within the bundles, xylem in grouped in radial rows of two to four vessels, phloem formed of two to three rows of cells, caps of sclerenchyma (one to three layers) associated with phloem and mainly xylem.

Discussion

We find that most of the studied species are petiolate (61%), simple (68%) and microphyll (29%). The laminar shape is most often ovate (45%) with some type of vascularized margin projections in 62% of the species. The brochidodromous venation pattern predominates (62%), followed by actinodromous (33%); areole development is moderate in 86% of the species and the freely ending veinlets are simple and curved in 53% of these; 90% of the species have looped marginal ultimate venation. The leaves are amphistomatic (66%) with anomocytic stomata (62%). Seventy four percent of the species have striate cuticle. The surface of 75% of the species is pubescent. The stomata of 77% of the species are at the same level as the rest of the epidermal cells. Epidermal cells in superficial view are tetragonal-elongated with S-undulated anticlines (63%). Almost all species (98%) have a vascular bundle sheath, but only in 73% of these there are sheath extensions, whereas sclerified cells associated with bundle sheaths are rare in the species studied, as in other members of the family (Aytas-Akcin and Akcin, 2017). Bundle sheaths have also been recorded for other taxa of Asteraceae (Bombo et al., 2012; Chwil et al., 2015; Mendes et al., 2016; De Sousa et al., 2018; Lusa et al., 2018) and they appear to be one of the most common traits in the family.

Although we did not find a unique combination of characters for any of the tribes, some patterns exist. For instance, the brochidodromous venation pattern appears to be the most common trait in most tribes, except in Senecioneae which has three different types (parallelodromous, actinodromous suprabasal and mixed craspedrodromous); this is consistent with Rojas-Leal et al. (2018), who found four venation patterns for the Mexican genera of the Senecioneae tribe. Stomata raised above epidermal cells appear to be a trait more common in the Eupatorieae as well as a particular type of midvein contour (adaxially flat or slightly projected and abaxially round or square protruded or highly protruded). This combination of characters has been recorded in other members of this tribe (Milan et al., 2006; Santos et al., 2016). The presence of paraveinal mesophyll and bundle sheaths without girders are common in the Tageteae tribe whereas the presence of bundle sheaths with extensions and canals associated with them is a common feature in the Heliantheae as recorded for other members (Bombo et al., 2012). The occurrence of abundant sclerified cells associated with vascular bundles in the lamina and the midvein in A. cordata is a distinctive feature of the Nassauvieae compared to the other tribes studied. The midvein contour which is flat or slightly convex adaxially and round and protruded abaxially, is a common trait of the Pseudognaphalium species studied (Gnaphalieae). In the Millerieae, the midvein contour (adaxially projected and abaxially slightly protruding or round and conspicuously protruded) is common to the three species studied, which also represent three genera. Sampling more species of all tribes of Asteraceae will allow improving not only the tribal descriptions, but also confirm the traits just mentioned for some tribes or find additional ones.

In the Asteraceae tribes studied there is a predominance of small leaf size, serrate margins, poorly developed areole development and the presence of bundle sheath extensions. This combination of characters has been related to efficiency in leaf hydraulic conductance (Sack and Scoffoni, 2013; Sack et al., 2015), light absorption (Nikolopoulos et al., 2002) and biomechanical support (Read and Stokes, 2006). Rivera et al. (2017) tried to explain leaf variation in this xerophytic scrub associating it with different drought-resistance strategies (Ferraro and Scremin-Dias, 2018). However, their results showed that leaf variation could not be solely explained by dry conditions promoted by the volcanic outcrop rocks. Rivera et al. (2017) suggest that characters as plant lifespan, growth form, genome size and species biogeographic history help explain the leaf variation since this attributes have been found related to different extents with anatomical characters in different plant species (Press, 1999; Santiago and Wright, 2007). Detailed anatomical and architectural descriptions are the first steps for any exhaustive study on the causes of leaf variation.

Conclusions

Here we present leaf characters occurring in the thirteen tribes of the Asteraceae present in the REPSA. There is significant variation in leaf architecture and anatomy in this area. The variation observed is consistent with the diversity reported for other authors for the family and for some Mexican tribes. The results of this descriptive study will allow testing evolutionary and ecological hypotheses about the effect of intrinsic and extrinsic factors of the species on the leaf diversity in this area. We suggest future avenues of research on the leaf anatomy of Asteraceae following the format and the terms used in our descriptions of the tribes. We consider that this model will allow standardization of leaf descriptions without losing useful information. Anatomical descriptions are a fundamental piece of the evolutionary, ecological and physiological study of the leaves in Asteraceae.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)