Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Acta botánica mexicana

On-line version ISSN 2448-7589Print version ISSN 0187-7151

Act. Bot. Mex n.81 Pátzcuaro Oct. 2007

Bromeliad flora of Oaxaca, Mexico: richness and distribution

Flora bromeliológica de Oaxaca, México: riqueza y distribución

Adolfo Espejo-Serna1, Ana Rosa López-Ferrari1, Nancy Martínez-Correa1 and Valeria Angélica Pulido-Esparza2

1 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Departamento de Biología. Herbario Metropolitano, Apdo. postal 55-535, 09340 México, D.F., México. aes@xanum.uam.mx.

2 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur - San Cristóbal de las Casas, Laboratorio de Análisis de Información Geográfica y Estadística, Chiapas, México. feliscatus@yahoo.com.

Recibido en julio de 2006

Aceptado en julio de 2007

ABSTRACT

The current knowledge of the bromeliad flora of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico is presented. Oaxaca is the Mexican state with the largest number of bromeliad species. Based on the study of 2,624 herbarium specimens corresponding to 1,643 collections, and a detailed bibliographic revision, we conclude that the currently known bromeliad flora for Oaxaca comprises 172 species and 15 genera. All Mexican species of the genera Bromelia, Fosterella, Greigia, Hohenbergiopsis, Racinaea, and Vriesea are represented in the state. Aechmea nudicaulis, Bromelia hemisphaerica, Catopsis nitida, C. oerstediana, C. wawranea, Pitcairnia schiedeana, P. tuerckheimii, Racinaea adscendens, Tillandsia balbisiana, T. belloensis, T. brachycaulos, T. compressa, T. dugesii, T. foliosa, T. flavobracteata, T. limbata, T. maritima, T. ortgiesiana, T. paucifolia, T. pseudobaileyi, T. rettigiana, T. utriculata, T. x marceloi, Werauhia pycnantha, and W. nutans are recorded for the first time from Oaxaca. Collections from 226 (of 570) municipalities and all 30 districts of the state were studied. Among the vegetation types occurring in Oaxaca, oak forest is the richest with 83 taxa, followed by tropical deciduous forest with 74, and cloud forest with 73 species. Species representation and distribution in Oaxaca are analyzed in detail. We also provide a comparison with bromeliad floras of the states of Chiapas, Guerrero, Puebla and Veracruz. The analysis of the species and collections by altitudinal intervals shows that the highest numbers of both ocurre between 1,500 and 2,000 m, with the number of species markedly decreasing above 2,500 m.

Key words: Bromeliaceae, distribution, diversity, endemism, flora, Mexico, Oaxaca.

RESUMEN

Se presenta el estado actual del conocimiento de la flora bromeliológica del estado de Oaxaca, México. La entidad ocupa el primer lugar en el país en cuanto a número de especies de Bromeliaceae se refiere. Los resultados obtenidos de la revisión de 2,624 ejemplares herborizados, correspondientes a 1,643 colectas, así como la revisión de bibliografía especializada, muestran que en el estado están presentes 172 especies agrupadas en 15 géneros. Bromelia, Fosterella, Greigia, Hohenbergiopsis, Racinaea y Vriesea tienen representados a todos sus taxa mexicanos. Se registran por primera vez para el estado: Aechmea nudicaulis, Bromelia hemisphaerica, Catopsis nitida, C. oerstediana, C. wawranea, Pitcairnia schiedeana, P. tuerckheimii, Racinaea adscendens, Tillandsia balbisiana, T. belloensis, T. brachycaulos, T. compressa, T. dugesii, T. foliosa, T. flavobracteata, T. limbata, T. marítima, T. ortgiesiana, T. paucifolia, T. pseudobaileyi, T. rettigiana, T. utriculata, T. x marceloi, Werauhia pycnantha y W. nutans. Se registraron colectas para 226 municipios de los 570 y para el total de los distritos (30) en los que está dividido políticamente el estado. Se hizo una comparación de la flora bromeliológica de Oaxaca con la de Chiapas, Guerrero, Puebla y Veracruz. De los tipos de vegetación presentes, el Bosque de Quercus es el que presenta mayor riqueza de taxa (83), seguido por el Bosque Tropical Caducifolio (74) y el Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña (73). El análisis del número de especies y de colecciones por intervalo altitudinal muestra que las cantidades más altas, tanto de colectas como de especies, se concentran entre los 1,500 y los 2,000 m s.n.m., disminuyendo claramente por arriba de los 2,500 m.

Palabras clave: Bromeliaceae, distribución, diversidad, endemismo, flora, México, Oaxaca.

INTRODUCTION

The Bromeliaceae contain approximately 3,086 species in 56 genera (Luther. 2006); in Mexico there are 18 genera and 342 species (Espejo et al., 2004). The family is well distributed across the country, as well as in all the vegetation types sensu Rzedowski (1978). It is a valuable component of many different plant associations, not only for the shear abundance of its species but also for the ecological role they play.

The family is important on many levels. Ecologically they are central epiphytic components in various ecosystems, possessing various physiological adaptations for atmospheric stress and serving as unique habitats for many animal species. Economically, bromeliads are valuable because of their ornamental and edible species.

Their floristic importance relates to their wide distribution throughout the Neotropics and the high number of narrowly endemic species. Despite these factors, the family has received relatively little attention with regard to floristic studies.

Although there are various regional treatments for the Mexican Bromeliaceae (e.g., McVaugh (1989), Utley and Burt-Utley (1994), Victoria (2001), Arellano Mijangos (2002), Pulido-Esparza et al. (2004), Espejo et al. (2005), and Ramírez-Morillo et al. (2004)), the only two contributions of national scope are those of Smith and Downs (1974; 1977; 1979) and Espejo et al. (2004). The purpose of this article is to provide an updated list of the members of the family in Oaxaca, with emphasis on aspects of endemism and geographic distribution.

Study area

Oaxaca is located in the southern portion of Mexico between 15°39' and 18°09' N latitude and 93°52' and 98°32' W longitude and covers an area of 93,343 km2, 4.8% of the country's surface (Anonymous, 2004) (Fig. 1). The state is politically divided into 30 districts and 570 municipios that include more than 10,000 towns and villages (Anonymous, 2004). It also is divided economically into eight regions: Cañada, Costa, Istmo, Mixteca, Papaloapan, Sierra Norte, Sierra Sur, and Valles Centrales (Anonymous, 2004).

Five physiographic regions are distinguished in Oaxaca (Anonymous, 2004): 1) Sierra Madre del Sur, 2) Cordillera Centroamericana, 3) Llanura Costera del Golfo sur, 4) Eje Neovolcánico, and 5) Sierras de Chiapas y Guatemala. Elevation varies from sea level along the coastal plains at the Pacific Ocean to 3,000 m in the "Sierra Madre de Oaxaca" (Ortíz-Pérez et al., 2004).

Also, five climatic regions are distinguished in Oaxaca (Trejo, 2004): 1) Cuenca del Balsas, 2) Sierra Madre del Sur y Llanura Costera, 3) Mixteca y Valles de Oaxaca, 4) Sierra Madre de Chiapas y Llanura Costera, and 5) Sierra Madre Oriental.

The climatic and physiographic variation is reflected in the diversity of vegetation communities that exists in Oaxaca, and these communities possess the greatest biological diversity of all Mexican states. Within the state the following types of vegetation (sensu Rzedowski, 1978) have been reported: Bosque Tropical Perennifolio, Bosque Tropical Subcaducifolio, Bosque Tropical Caducifolio, Bosque Espinoso, Matorral Xerófilo, Bosque de Quercus, Bosque de Coniferas, Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña, Palmar, Bosque de Galería,Vegetación Acuática y Subacuática.

METHODS

From June of 1997 until June of 2006, Oaxacan specimens from the following herbaria were examined, identified, annotated, and captured in a database: B, BM, BR, C, CHAP, CICY, CIIDIR, CODAGEM, ECON, ENCB, F, FCME, FI, GH, GOET, HEID, IBUG, IEB, K, LG, LL, M, MA, MEXU, MICH, MO, NY, OXF, P, SEL, SERO, TEX, UAMIZ, UC, UNICACH, US, VT, WU, XAL, and Z. The information from these specimens was enhanced by a carefull revision of pertinent bibliographic material (Baker, 1889; Mez, 1896; Smith, 1961; Smith & Downs, 1974; 1977; 1979; Grant, 1995 a; b; Palací, 1997; Till, 1990, 1992).

In order to analyze the distribution of the species, geographic coordinates were obtained from the labels of the examined specimens. These were checked and corrected if necessary, and subsequently, the data were processed in the program Arc View GIS 8 (Anonymous, 2003). In instances where such information was lacking, the location was obtained from topographic 1:250,000 scale maps (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI) maps D14-3, E14-6, E14-8, E14-9, E14-12, E15-7 and E15-10), and from the web site http://mapserver.inegi.gob.mx/dsist/ahl2003/index.html?c=424.

Two data matrices for species presence-absence were constructed, one relative to the vegetation types and other relative to the adjacent states (Guerrero, Chiapas, Puebla, and Veracruz). These matrices were used to obtain Jaccard indices of similarity. Also, cluster analyses were done in order to determine the affinities of the Oaxacan bromeliad flora with respect to that of the adjacent states and to evaluate the similarity of the flora with respect to the types of vegetation present in the state. These analyses were conducted using the program NTSYSpc2.0 (Rohlf, 1998).

A species accumulation curve was generated to assess the knowledge and extent of exploration of the states bromeliad flora. The collection year information used to generate this curve was obtained directly from herbarium labels, using as a sample the total number of species recorded each five years. The starting point was 1840, the year of the first known collection of Bromeliaceae in Oaxaca. In addition, a rarefaction curve, taking into account the abundance of each taxon, was generated (Colwell & Coddington, 1994) to compare the data obtained in the accumulation curve with that expected using Chao1 and Jacknife 2 estimators (Chao, 1984; Colwell & Coddington, 1994). The algorithms were calculated with the program EstimatesS Ver. 7 (Colwell, 2004).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

After examining 2,624 herbarium sheets, corresponding to 1,643 collections, we can say now that the known bromeliad flora of the state is composed by 172 species and 15 genera (appendix). This figure represents 50.29% of the 342 species of the family registered for the country (Espejo et al., 2004). In contrast, the two previous publications that provide integral information about the bromeliad Flora of Oaxaca, Flora Neotropica (Smith & Downs, 1974, 1977, 1979) and the Checklist of Mexican Bromeliaceae (Espejo et al., 2004), reported 14 genera, 88 species based on 213 collections and 15 genera, 135 species based on 1482 collections, respectively.

The genera with the greatest number of species in the area are Tillandsia (101 spp.) and Hechtia (20 spp.). In contrast, Billbergia, Fosterella, Guzmania and Hohenbergiopsis each possess a single species. Bromelia, Fosterella, Greigia, Hohenbergiopsis, Racinaea, and Vriesea have all their Mexican taxa represented in Oaxaca. The following species are reported from the state for the first time: Aechmea nudicaulis, Bromelia hemisphaerica, Catopsis nitida, C. oerstediana, C. wawranea, Pitcairnia schiedeana, P. tuerckheimii, Racinaea adscendens, Tillandsia balbisiana, T. belloensis, T. brachycaulos, T. compressa, T. dugesii, T. foliosa, T. flavobracteata, T. limbata, T. maritima, T. ortgieseana, T. paucifolia, T. pseudobaileyi, T. rettigiana, T. utriculata, T. x marceloi, Werauhia nutans, and W. pycnantha.

Oaxaca, with 43 narrowly endemic species (Appendix; Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22), possesses a higher number of endemics than any other state in the country. These endemics belong to four genera: Hechtia (13 spp.), Pitcairnia (1 sp.), Tillandsia (28 spp.), and Viridantha (1 sp.). Of all species present in the state, 95 (55.23%) are endemic to Mexico and represent eight genera: Bromelia (2 spp.), Catopsis (1 sp.), Greigia (2 spp.), Hechtia (20 spp.), Pitcairnia (6 spp.), Tillandsia (59 spp.), Viridantha (4 spp.) and Werauhia (1 sp.).

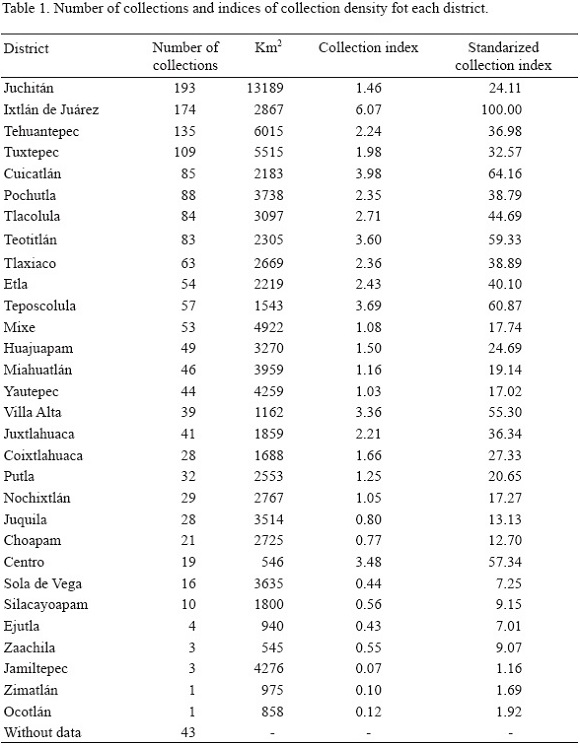

It is worth pointing out that the majority of the Bromeliaceae collections are concentrated in the north, north-west and center portions of the state along its principal roadways (Fig. 1). Collections are known from 226 (39.64%) of the 570 municipalities and from all of the districts (Table 1).

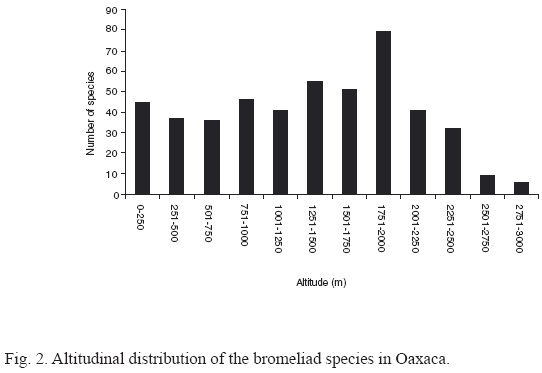

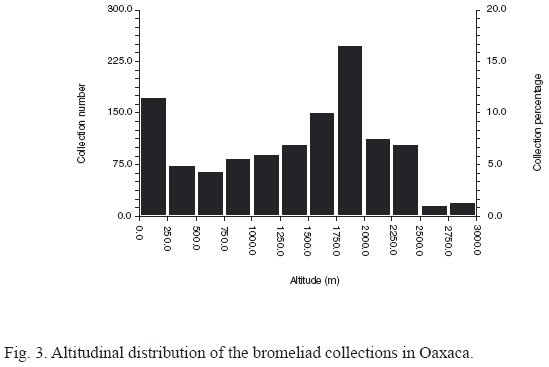

The analysis of species number by altitude (Fig. 2) shows that 79 species, or 45.93 % of the total, ocurr between 1,750 and 2,000 m. The altitudinal average varies between 30 and 45 species in the other altitudinal intervals, and decreases suddenly above 2,500 m. A similar analysis for the collections is showed in figure 3. The graph shows two peaks, one between 0 and 250 m and another between 1,750 and 2,000 m. The distribution of the collections between intervals is heterogeneous.

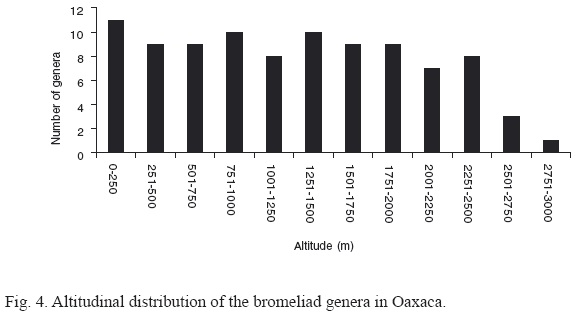

Concerning genera (Fig. 4), their distribution is more or less homogeneous, the average varying between 7 and 11 genera per altitudinal interval, and, as with species, they decrease suddenly above 2,500 m. All the Oaxacan species of Aechmea, Billbergia, Bromelia, Fosterella, Guzmania, and Vriesea, grow below 1,500 m. The genus Tillandsia is well represented from the sea level to 3,000 m.

The species accumulation curve (Fig. 5) shows that even though there has been a substantial increase in the number of Bromeliaceae species and collections reported, the asymptote had not been reached. This suggests that the state has not been sufficiently explored. The rarefaction curve, and the Chao and Jacknife estimates show that the predicted number of Bromeliaceae species for the state varies between 219 and 243, and thus between 50 and 74 species remain to be encountered yet.

These results can be explained by the fact that there is a tendency to collect along highways and roads, and this has led to a disproportionate amount of collecting in relatively few areas. In contrast, there are many areas that have not been explored at all. For example, of the 570 municipalities, only in 226 are known collections of Bromeliaceae. In order to increase our knowledge about the floristics and biogeography of the family in the state, it is necessary to undertake a much more extensive sampling in areas that are far from the principal roads. However, it should be noted that a large portion of Oaxaca (and Mexico in general) has suffered severe loss of primary vegetation, and it is therefore possible that even with an extensive collecting effort, few new records may be found.

With respect to the comparison between the bromeliad flora of Oaxaca with that of the neighbour states, the dendrogram shows that the Floras of Chiapas and Veracruz are very similar and both, as a group, are highly similar to that of Oaxaca (Fig. 6).

The similarity of the Oaxacan bromeliad flora with that of Chiapas-Veracruz is mainly attributed to the Mesoamerican influence in these states. Another factor is the continuous extension of vegetation between these three states, that is represented by tropical forest that extends from northern South America through Central America. The southern states of Mexico represent the northernmost limit of the distribution of various taxa, and in these states the geographic and biological conditions have generated a particular flora. Puebla also shares some elements with the Oaxaca-Chiapas-Veracruz group, but is clearly separate from them (Jaccard index = 0.22). Puebla appears to possess a much stronger influence from the Eje Neovolcanico Transmexicano and the Sierra Madre Oriental. The bromeliad flora of Guerrero has the least similarity in comparison that of the other states analyzed (Jaccard index = 0.21).

Although Oaxaca shares many floristic elements with adjacent regions, it represents a special case, due to its great ecological diversity, ranging from the arid regions of the north to the coastal regions and central zones, the latter of which include cloud forests and a grand extension of coniferous forests (Table 2).

With regard to the comparison of bromeliads among the types of vegetation present in the state, the dendrogram (Fig. 7) shows that if we exclude from the analysis the Palmares (because it is generally found distributed in small patches within other types of vegetation where it is associated with humid and generally warm climates or secondary vegetation), there are two main groups (Jaccard Index = 0.04). One contains the majority of the vegetation types (seven in total). Within this graph Bosque de Coníferas and the Bosque de Quercus are the most similar (Jaccard Index = 0.39) and are grouped with the Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña (Jaccard Index = 0.32). The second main group encompasses two subgroups: one conformed by the Vegetación Acuática (mainly Manglares) and the Bosque Espinoso which are always found in the southeast coastal region of the state, and the other represented by the Bosque Tropical Subcaducifolio. Factors such as soil type, temperature and humidity microhabitats and other environmental conditions where these communities are found could be why the bromeliad floras are so similar within these vegetation types.

Of the 11 types of vegetation (sensu Rzedowski, 1978) present in the state, the Bosque de Quercus is the richest in number of species (83), followed by Bosque Tropical Caducifolio with 74 species, and Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña with 73 taxa. Five species are restricted to Bosque de Coníferas: Tillandsia festucoides, T. leucolepis T. quaquaflorifera, T. x marceloi, and T. wuelfinghoffi. Thirteen species are known only from Bosque de Encino: Bromelia hemisphaerica, Hechtia nuusviorum and two undescribed species of Hechtia, Pitcairnia schiedeana, P. tuerckheimii, Tillandsia atroviolacea, T. lampropoda, T. rettigiana, T. rubrispica, T. ulrici, T. yerbasantae, and Viridantha penascoenesis. Thirteen species are exclusive to Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña: Catopsis nitida, C. oerstediana, Greigia vanhyningi, Racinaea adscendens, Tillandsia belloensis, T. copalaensis, T. Jcirchhoffiana, T. kolbii, T. laui, T. lautneri, T. leiboldiana, T. mixtecorum, and Werauhia nocturna. Seventeen species are confined to Bosque Tropical Caducifolio: Hechtia caudata, H. fosteriana, H. fragilis, H. lanata, H. lymansmithii, H. marnierlapostollei, and three additional undescribed species, Tillandsia atenangoensis, T. califanii, T. glabrior, T. ortgiesiana, T. pseudobaileyi, T. schatzlii, T. schusteri, and T. vernardoi. Twelve species are limited to Bosque Tropical Perennifolio: Aechmea magdalenae, A. nudicaulis, Catopsis wawranea, Pitcairnia undulata, Tillandsia flavobracteata, T. foliosa, T. limbata, T. pruinosa, Vriesea heliconioides, V. malzinei, Werauhia gladioliflora, and W. nutans. Tillandsia socialis grows only in Bosque Tropical Sub-caducifolio. Two species are restricted to Matorral Xerófilo: Hechtia confusa, and Viridantha mauryana. Tillandsia balbisiana occurs solely in Bosque Espinoso.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following herbaria for providing specimens and data used in this work: B, BM, BR, C, CHAP, CICY, CIIDIR, CODAGEM, ECON, ENCB, F, FCME, FI, GH, GOET, HEID, IBUG, IEB, K, LG, LL, M, MA, MEXU, MICH, MO, NY, OXF, P, SEL, SERO, TEX, UAMIZ, UC, UNICACH, US, VT, WU, XAL, and Z; the Elizabeth Bascom Fellowship for Latinoamerican Women and the Missouri Botanical Garden for a scholarship granted to the second author; Jacqueline Ceja Romero and Aniceto Mendoza Ruiz for their invaluable and constant help in the field work; Victor Steinmann for his help with the English translation; and Javier García-Cruz suggestions and improvements to the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

Anonymous. 2003. ESRI. ArcView Ver. 8.1. [ Links ]

Anonymous. 2004. Síntesis de Información Geográfica del Estado de Oaxaca. Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Aguascalientes. 166 pp. [ Links ]

Arellano Mijangos, J. J. 2002. Las Bromeliaceae del Estado de Oaxaca: Riqueza florística y potencial ornamental. Tesis profesional. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Centro Universitario del Sureste. San José Puyacatengo, Tabasco. 135 pp. [ Links ]

Baker, J. G. 1889. Handbook of the Bromeliaceae. George Bell & Sons. London. 243 pp. [ Links ]

Chao, A. 1984. Nonparametric estimation of the numbers of classes in a population. Scandinavian J. Stat. 11: 265-270. [ Links ]

Colwell, R. K. 2004. Estimates: statitistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 7. User's guide and application. 2006 (http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/estimates). [ Links ]

Colwell, R. K. & J. A. Coddington. 1994. Estimating terrestrial biodiversity through extrapolation. Philos. Trans., Ser. B. 345: 101-188. [ Links ]

Espejo, A., A. R. López-Ferrari, I. Ramírez-Morillo, B. K. Holst, H. E. Luther & W. Till. 2004. Checklist of Mexican Bromeliaceae with notes on species distribution and levels of endemism. Selbyana 25(1): 33-86. [ Links ]

Espejo, A., A. R. López-Ferrari & I. Ramírez-Morillo. 2005. Bromeliaceae. Flora de Veracruz 136. Instituto de Ecología, A. C. Xalapa, Veracruz. 307 pp. [ Links ]

Grant, J. 1995a. Bromelienstudien. The resurrection of Alcantarea and Werauhia, a new genus. Trop. Subtrop. Pflanzenw. 91: 1-57. [ Links ]

Grant, J. 1995b. Addendum to The resurrection of Alcantarea and Werauhia, a new genus (Bromeliaceae; Tillandsioideae). Phytologia 78(2): 119-123. [ Links ]

Luther, H. E. 2006. An alphabetical list of bromeliad binomials. Bromeliad Society International. Sarasota. 119 pp. [ Links ]

McVaugh, R. 1989. Bromeliaceae. In: Anderson, W. R. (ed.). Flora Novo-Galiciana. The University of Michigan Herbarium. Ann Arbor. pp. 4-79. [ Links ]

Mez, C. 1896. Bromeliaceae. In: De Candolle, C. Monographiae Phanerogamarum 9: 1990. [ Links ]

Ortiz Pérez, M. A., J. R. Hernández Santana & J. M. Figueroa Mah-Eng. 2004. Reconocimiento fisiográfico y geomorfológico. In: García-Mendoza, A. J., M. J. Ordóñez & M. Briones-Salas (eds.). Biodiversidad de Oaxaca. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Fondo Oaxaqueño para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, World Wildlife Fund. México, D.F. pp. 43-54. [ Links ]

Palací, C. A. 1997. A systematic revision of the genus Catopsis (Bromeliaceae). Ph. D. Thesis. University of Wyoming. Laramie, Wyoming. 245 pp. [ Links ]

Pulido-Esparza, V. A., A. R. López-Ferrari & A. Espejo. 2004. Flora bromeliológica del Estado de Guerrero, México: riqueza y distribución. Bol. Soc. Bot. Méx. 75: 55-104. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Morillo, I., G. Carnevali Fernández-Concha & F. Chi May. 2004. Guía ilustrada de las Bromeliaceae de la porción mexicana de la Península de Yucatán. Centro de Investigaciones Científicas de Yucatán, A. C. Mérida, Yucatán. 124 pp. [ Links ]

Rohlf, F. J. 1998. NTSYSpc. Numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. Version 2. User guide. University of New York. Stony Brook, New York. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de México. Limusa. México, D.F. 432 pp. [ Links ]

Smith, L. B. 1961. Notes on Bromeliaceae, XVII. Phytologia 8(1): 1-13. [ Links ]

Smith, L. B. & R. J. Downs. 1974. Pitcairnioideae (Bromeliaceae), Flora Neotropica 14(1): 1-658. [ Links ]

Smith, L. B. & R. J. Downs. 1977. Tillandsioideae (Bromeliaceae), Flora Neotropica 14(2): 659-1492. [ Links ]

Smith, L. B. & R. J. Downs. 1979. Bromelioideae (Bromeliaceae), Flora Neotropica 14(3): 1493-2142. [ Links ]

Till, W. 1990. Altbekannt - und trotzdem neu: Tillandsia fuchsii, spec. nov. Bromelie 1990(2): 30-33. [ Links ]

Till, W. 1992. A well-known new species: Tillandsia fuchsii. J. Bromeliad Soc. 42(5): 99102. [ Links ]

Trejo, I. 2004. Clima. In: García-Mendoza, A. J., M. J. Ordóñez & M. Briones-Salas (eds.). Biodiversidad de Oaxaca. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Fondo Oaxaqueño para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, World Wildlife Fund. México, D.F. pp. 67-85. [ Links ]

Utley, J. & K. Burt-Utley. 1994. Bromeliaceae. In: Davidse, G., M. Sousa Sánchez & A. O. Chater (eds.). Alismataceae a Cyperaceae. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Biología, Missouri Botanical Garden, The Natural History Museum (London). México, D.F. pp. 89-156. [ Links ]

Victoria, A. 2001. Bromeliaceae. In: Rzedowski, G. C. de, J. Rzedowski y colaboradores. Flora Fanerogámica del Valle de México. 2a. ed. Instituto de Ecología, A.C. y Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Pátzcuaro, Michoacán. pp. 1179-1187. [ Links ]