Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Estudios fronterizos

On-line version ISSN 2395-9134Print version ISSN 0187-6961

Estud. front vol.23 Mexicali 2022 Epub Oct 03, 2022

https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2220104

Articles

Gendered migration and borders control regime. The production of expulsability in Argentina

a Conicet/Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, e-mail: rosas.carol@gmail.com

b Conicet/Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, e-mail: sandragilaraujo@yahoo.es

This article corresponds to the critical studies on the immigration and border control regime and contributes to the knowledge that this regime acquires in the South American region, specifically in Argentina. It focuses on the dimension of expulsability, which refers to the legal and administrative tools that make possible the legal production of migratory illegality. The objective is to analyze, from a gender perspective, the statistical evolution of three state tools between 2010 and 2020: denial of entry, residence cancellations and administrative expulsion orders. The normative context is also analyzed, and specialized literature is reviewed. This study suggests that, as in the countries of the global north, in Argentina the production of expulsability is masculinized. It is essential to attend to the gendered migration control, incorporating an intersectional and situated perspective, which considers the differential effects on men, women and other gender identities.

Keywords: migration control; expulsability; gender; Argentina

Este artículo se inscribe en la línea de estudios críticos sobre régimen de control migratorio y fronterizo, y aporta al conocimiento de la forma que este régimen adquiere en Sudamérica, específicamente en Argentina. Se focaliza en la dimensión de la expulsabilidad, que remite a las herramientas legales y administrativas que posibilitan la producción legal de la ilegalidad migratoria. El objetivo es analizar, desde una perspectiva de género, la evolución estadística de tres herramientas estatales (2010-2020): rechazos de ingresos, cancelaciones de residencia y disposiciones por expulsión. También se examina el contexto normativo y la literatura especializada. El estudio realizado sugiere que, como en los países del norte global, en Argentina la producción de la expulsabilidad está masculinizada. Resulta fundamental, entonces, atender a la generización del control migratorio, incorporando una perspectiva interseccional y situada que contemple los efectos diferenciales sobre varones, mujeres y otras identidades de género.

Palabras clave: control migratorio; expulsabilidad; género; Argentina

Introduction

In recent decades, international migration has gradually become a priority target of policies to govern populations globally (Fassin, 2011). The strengthening of discourses and constraining laws has promoted the criminalization of the migrant population classified as illegal or irregular and their exclusion from the rights field. At the same time, the number and the categories of migrants subject to arrest, detention, and expulsion/deportation have increased and diversified (De Genova, 2019; Domenech, 2020).

The legal creation of illegality and, therefore, of expulsable subjects is one of the central mechanisms of the global migration and border control regime in force. The concept of regime refers both to the set of regulations, practices, and narratives historically configured by various actors to regulate and control international mobility and its effects, and to the resistance of migrants themselves (Clavijo & Gil Araujo, 2021; Domenech & Dias, 2020; Hess, 2010). Consequently, while the aforementioned global regime leads to the international hierarchization and stratification of mobility and runs through the lives of migrants, it is constantly being redefined and reconfigured in the framework of their struggles.

Of this set of regulations, practices, and narratives designed to control migration, this paper is interested in those state tools that various authors associate with expulsability.1 For Sayad, expulsability is contained in the very condition of (im)migrant, insofar as, according to the national ideology, non-national presence is intrinsically illegitimate and therefore provisional. The national order implies that “to be an immigrant and to be expulsable, to be an immigrant and to be excludable from politics are one and the same thing” (Sayad, 2008, p. 113). De Genova (2010, 2019) understands that deportability refers to the legal and administrative framework that enables the legal production of migrant illegality and, thus, enables immigrants to be expulsables at any time from the country of immigration and from their jobs, which facilitates their disciplining and exploitation. That is, it is expulsability as the possibility of being expulsable, and not deportation per se, which historically “keeps foreigners in a state of permanent temporariness” (Domenech, 2017, p. 35). In order to analyze this concept, following Domenech, it is necessary to address non-admission or rejections at the border, the processes of access to documentation and migratory regularity, and the application of new technological tools (biometrics), among other state practices.

However, some migrants are more susceptible to expulsion (i.e., they are more expulsable) than others, depending on specific political and historical contexts. Indeed, for De Genova (2019) there is an economy of deportability, that is, unequal distribution of the forms assumed by state power over the lives and freedoms of non-nationals, as well as of the rationalities and techniques or technologies deployed in the administration or governance of migrants’ lives. This stratification is configured according to a series of meanings attributed to migrants based on gender, sexuality, age, social class, national origin, and migratory status, among other characteristics.

Inspired by this discussion, these pages speak of an economy of expulsability, specifically focusing on the gender dimension. In other words, they explore the gendered nature of migration control. The term gendered is used to conceptualize the role of gender in the production of expulsable populations.2 From this analytical approach, an approximation is made to the differential effects on men and women of the legal and administrative tools that produce migratory illegality and, therefore, the possibility of being subject to expulsion. As detailed below, this field of study has paid greater attention to the characteristics of class, race, and national origin, but less attention has been paid to the importance of gender. However, its significance is clearly manifested when it is observed for example that arrests, detentions, and expulsions affect more people who at birth were identified as male; while controls, arrests, and expulsions in the framework of anti-trafficking policies impact more on cis and transgender women (Golash-Boza, 2016; Hess, 2013; Fernández Bessa, 2019; Piscitelli & Lowenkron, 2015).

Based on this background, this study proposes to examine the Argentine case and, thus, contribute to the knowledge of the dimension of expulsability and its economy in the South American region.3 The aim is to analyze, from a gender perspective, the statistical evolution of three state tools that produced expulsability between 2010 and 2020: refusals of entry, residency cancellations, and administrative expulsion orders. In order to contextualize the trends expressed by the statistical data, an analysis of the regulations and practices deployed in the period considered is presented,4 together with a review of the specialized literature to support the discussion and interpretations suggested by the data.

Regarding the article’s structure, after the methodological notes, the following section summarizes the specificities of the South American migration and border regime in the framework of the globalization of control. This is followed by a review of the precedents that have paid attention to the gender dimension of migration and border control. Subsequently, the Argentine case is addressed, based on the analysis of the quantitative evolution of the refusals of entry, cancellations of residency, and administrative expulsion orders in the period 2010-2020, which shows their gendered nature. The article concludes with a synthesis of the main findings and suggestions for future lines of reflection and research.

Methodological notes

The methodological approach is mixed. On the one hand, descriptive statistics were produced from the processing of quantitative data tabulations requested from the National Directorate of Migration (DNM, by its acronim fron spanish Dirección Nacional de Migraciones) to prepare this article. Specifically, the three indicators selected (refusals of entry, cancellations of residency, and expulsion orders issued by the DNM) are analyzed according to the gender and nationality of the persons who are the subjects of these procedures for the years 2010-2020.5 In addition, the gender composition of the procedures initiated by migrants to enter or settle in the country is synthetically described. Thus, it is possible to establish (in)consistencies between the gender composition of the procedures initiated by migrants and those initiated by the DNM.6

It is important to consider that the tabulations used are derived from administrative records7 that account for movements and procedures but not persons; in fact, the same person may appear in the records more than once. In a limited time, the latter may be more frequent in the case of procedures related to entries, exits, and temporary residency but less frequent in the case of procedures related to permanent residency, administrative expulsion orders, and actual expulsions. Likewise, there is no information to determine whether there are more women or men in these repetitions, nor are there arguments to generate assumptions in this regard; rather, this could be the subject of future analysis from a gender perspective.

It is also necessary to point out that the reports provided by the DNM are organized based on the variable “sex” and the categories “female” and “male”, which prevents differentiating transgender/transvestite persons. Not only was the information requested not provided, but also the following query was not answered: “Information is requested on whether the DNM registers transgender/transvestite persons as such. If not, please explain how they are registered”. Therefore, the statistical registry is based on a binary conception of gender incompatible with Law No. 26.743/2012 on gender identity in force in Argentina.

Moreover, these official data do not reveal daily micro-control practices, which can only be accessed through ethnographic observations and interviews. That is to say, there are subtle controls that cannot be identified in these statistical data. Even so, given the scarcity of suitable sources for the migration issue in Argentina, undoubtedly the information produced by the DNM allows for the development of assumptions and lines of inquiry that contribute to knowledge.

On the other hand, a documentary analysis was conducted by compiling laws, decrees, and resolutions issued by the DNM between 2010 and 2020, which relate to the topics analyzed. As can be seen, the agency producing the quantitative and documentary data analyzed is the DNM.8 It is an agency under the Ministry of the Interior, which is responsible for applying migration regulations and for the implementation of public policies in this area, in accordance with the directives of the National Government. It is central in this analysis because it is in charge of controlling, registering, filing, and processing everything related to the entry and exit of persons from the country and of granting, extending, and canceling residencies to foreigners, as well as administering expulsion orders. It directly controls (through inspectors, equipment, and technology) all border crossings (air, land and sea or river), while, due to its federal role and the personal database it compiles, it provides information to all national government and non-governmental agencies that require it, in accordance with the regulations in force. It uses the same digital online information tools with personal data from international and national sources. Finally, it is evident that the construction and dissemination of statistical data by official agencies is part of what Domenech (2020) calls official strategies of spectacularization of migration control. When publicized by the State, these data provoke social representations and contribute to the construction of migration as a threat.

Globalization of South America’s migration control and border regime

In recent decades, different authors have coincided in pointing out the influence of globalizing tendencies in the way migration is regulated, through the export of the migration control model from the Global North to other parts of the world, due to the work of organizations such as the International Organization for Migration (Duvell, 2015; Domenech, 2017; Santi, 2020). One of the clearest indicators of the gradual crystallization of a global migration control regime is the multiplication of instruments for the externalization, displacement, and delocalization of control (Gil Araujo, 2011). The view of migration and migrant populations as a threat drove the proliferation of measures, systems, and technologies for migration control at the borders and within the countries of destination (Domenech & Dias, 2020; Santi Pereyra, 2018), but also in the countries of transit and origin of migration (Gil Araujo et al., 2017; González et al., 2013; Trabalón, 2021). At the same time, in these channels, a growing number of new actors (public and private; formal and informal; governmental and non-governmental; local, national, international, and supranational) is merging with the central body of the State (Gil Araujo, 2005, 2011; Domenech, 2017). Thus, the global migration control regime is supported by a web of regulations, practices, and discourses that produce illegality (De Genova, 2010, 2019). However, it does not promote a hermetic closing of borders but rather a system of floodgates that, through closures and openings, drives the differential inclusion of migrant labor through its legalization (Mezzadra, 2012).

However, regimes take particular forms at regional and national levels, depending on the specific historical, geographical, and socio-political context; and they are transformed over time in relation to the reconfiguration of population movements and migrant struggles and resistance (Clavijo & Gil Araujo, 2021; Hess, 2010). Recently, Domenech and Dias (2020) characterized the South American migration and border regime in the framework of the internationalization and regionalization of migration policy, externalization of controls, and displacement of borders. Among the aspects that currently characterize this regime is the reconfiguration of migratory tendencies, in particular the diversification of migration origins (from the Caribbean, Africa, or Asia), the emergence of new countries of origin and destination of regional migration (such as Venezuela and Chile, respectively) and the tracing of new migration routes. In the area of control regulations and practices, the authors point out that over the last decade, the South American region has seen an increase in the changing and contingent nature of the measures regulating mobility, differential treatment of migrant populations, stricter entry requirements, increased controls within the national territory, the imposition of consular and humanitarian visas, the rejection of refugee applications and voluntary return programs, increased obstacles to obtaining documentation, the growing demand for documentation to access work, health, and education, the increase and extension of rejections at the border, arrests and expulsions, and the strengthening of the link between migration and criminal issues. As stated in the report of the Center for Legal and Social Studies and the Argentine Commission for Refugees and Migrants (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales y la Comisión Argentina para Refugiados y Migrantes, 2020, p. 64), although in South America, the number of expulsions is low compared to countries in the Global North,

the growing number of expulsions and the references to them in official discourse are other warning signs regarding the increasingly active role of penal systems in the punishment and disciplining of the popular sectors, including the migrant population.

Consistently with the characterization of the South American migration and border regime by Domenech and Dias (2020), the articles by Ramírez (2018), Herrera and Berg (2019), Correa Álvarez (2019), and Álvarez Velasco (2020) find that in Ecuador, regulations and practices were promoted that boosted the production of irregularity and deportations. For the case of Chile, Stang and Stefoni (2016), Stang Alva et al. (2020), and Dufraix Tapia et al. (2020) also confirm the growth of irregularization, non-admissions, expulsions and the deepening of the relationship between migration and criminal issues. From Brazil, Ruseishvili and Chaves (2020) warn about the configuration of deportability as a new paradigm of Brazilian migration policy. In Argentina, Jaramillo et al. (2020) find a vicious circle between the increase of permanent residency controls, difficulties in accessing documentation, the increase of irregularity, and the increase of expulsions between 2016 and 2019.9 Further research on Argentina, in addition to supporting these findings, demonstrates the increase in rejections at the border based on the concept of the “false tourist”, selectivity in controls, visa applications, datification, and other tools of migration control (Alvites Baiadera, 2018; Domenech, 2020; Santi Pereyra, 2018, Trabalón, 2021).

Most of these studies have highlighted the racialized or class-based nature of migration control regimes but have paid little attention to their gendered nature, as noted by Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo (2013). The following section reviews some of these background studies that inspired the analysis of the Argentine case.

The gendered nature of the global migration control and border regime

Critical studies on migration control, and in particular research on deportability/expulsability, have overlooked the impact of gender on the concrete forms these processes take.10 For example, De Genova and Roy point out that “... the law is deployed to target and expel bodies marked as dangerous and unruly. These bodies are disproportionately Black and Brown... and poor” (2019, p. 11). However, preceding studies allow us to affirm that in addition to Black, Brown, and poor, these imprisoned, detained, and expelled bodies are, in greater proportion, identified as male (Golash-Boza, 2016; Golash-Boza & Hondagneu Sotelo, 2013; Jarrín Morán, 2018). Specifically, Menjívar et al. (2018, p. 1) state that the criminalization of migration is intimately linked to the “racialization and gendering of certain groups of immigrants, particularly black and brown male bodies from the global South. As a result, a constructed, globalized immigrant ‘Brown threat’ is increasingly surveilled, imprisoned, and deported”.

Research on the gendered nature of migration control in destination countries is in its infancy and generally refers to countries of the Global North (Gil Araujo et al., 2022). Although each national context has its own specific circumstances, in Western European countries, migrant women have been constructed in policies and public discourse as vulnerable victims in need of protection,11 although in many cases, they have been the initiators of migration projects (Pedone et al., 2012). As a counterpoint to these perceptions, male migrants are often thought of as oppressive, violent, and dangerous. Several studies confirm that in European Union countries the victimization of migrant women has been accompanied by the criminalization of men (adults and youth) of Muslim origin (Block, 2019; Bonjour & Haart, 2013; Schrover & Moloney, 2013). As such, while female migrants are denied any agency, male migrants are expropriated of any semblance of humanity and vulnerability. In other words, “Men are a risk, women are at risk” (Schrover & Moloney, 2013, p. 255). These gender, racial, and national politics permeate how European governments think and act on the migrant presence coming from the Global South (Gil Araujo et al., 2017; Kofman, 2018; Pedone et al., 2012; Schrover & Moloney, 2013).

Additionally, the gender analysis of Golash-Boza and Hondagneu Sotelo (2013) notes a reconfiguration in the field of migration control in the United States in the last two decades. The increase in male unemployment, say the authors, coupled with changes in immigration law and the so-called war on terrorism, has led to greater criminalization of specific groups of male migrants. Thus, while no legislation explicitly articulates this shift, changes in U.S. policy and administrative practices have constructed a new immigrant danger, which is now masculine and personified by the male terrorist and criminal alien.12 This is materialized in thousands of arrests and deportations that are masculinized, racialized, and with a clear class bias; more specifically, Latin American and Caribbean working-class males. This is also borne out in the study on crimmigration, arrests and mass deportations by Menjívar et al. (2018) and the intersectional analysis of mass incarceration and deportations by Golash-Boza (2016). The data speak for themselves: by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, between 85% and 90% of deportees were male (Golash-Boza & Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2013).

Similar conclusions are presented by Jarrín Morán (2018) from a study on the deportation of Ecuadorian migrants from Spain. Although Spanish legislation does not explicitly prioritize the deportation of men, the data show a masculinization of arrests, detentions, and deportations, with a higher percentage of certain nationalities, where men of Moroccan origin are the most affected by these practices. Fernández Bessa (2019) confirms a gender gap in Spain, given that control, arrest, and deportation have a greater impact on males. This author states that in the deportation mechanism, the gender selectivity of criminal control is verified.

Furthermore, in recent years, in the United States and Europe,13 the dynamics of criminalization, illegalization, arrest, and deportation of migrants, and asylum seekers have been explored from a queer perspective. Among the most notable precedents, Luibhéid (2005) showed that in the United States, the exclusion of lesbians, gays, and transgender people has never functioned as an isolated system but has been part of a broader immigration control regime aimed at guaranteeing a sexual and gender order “adequate” for the reproduction of white racial privilege and the exploitation of the popular sectors.

In South America, the analysis of migration policies with a gender perspective is embryonic in the field of migration control. A precedent can be found in the work of Quinteros Rojas (2016), who, without incorporating a gender perspective in his analysis, indicates that in Chile, the number of deported men is double that of women, with an overrepresentation of Dominican and Bolivian nationalities. Another precedent that also does not make the gender aspect explicit is the analysis of anti-trafficking policies by Magliano and Clavijo (2013). They show that the association between human trafficking and female migration is based on considering migrant women as vulnerable beings, potential victims of criminal networks. Along the same lines, Gutiérrez Gómez (2018) describes the functioning of the anti-trafficking policy in Argentina, particularly how the use of anti-trafficking policy has served as a justification for controlling national borders and deporting or criminalizing migrants. Meanwhile, Trabalón (2021) looks at the link between the use of the figure of the trafficking victim and the process of racialization and sexualization of Dominican women in Argentina. At the same time, says this author, the control of Senegalese male migrants is configured around their relationship with criminalized activities, such as street vending.

Based on the cases of Spain and Brazil, the study by Piscitelli and Lowenkron (2015) shows how the discourse and legal regimes on human trafficking promote the criminalization of certain international displacements, marked by gender, sexuality, class, race/ethnicity, and nationality. Likewise, for the case of Ecuador, Ruiz Muriel and Alvarez Velasco (2019) analyze the anti-trafficking policies deployed under the government of Rafael Correa. They show that while trafficking was associated with women and girls being seen as helpless victims, smuggling was linked to men who migrate irregularly.

Finally, little progress has been made in the region regarding the analysis of heteronormative representations in the field of migration control. However, the need to promote “the production of studies that investigate the multiple forms and mechanisms of exclusion/inclusion of ‘dissident genders’ or LGBT or queer migration produced by mobility control policies and practices” (Domenech & Pereira, 2017, pp. 99-100) has been recognized. Along the same lines, Jaramillo and Rosas (2022) analyze the hetero-cis-normative biases that permeate Argentine migration policies, paying attention to how different types of laws (migration laws, gender identity laws, and punitive and criminal regulations on sex work and drug sales) are devised to hinder access to documentation and rights for South American transgender/transvestite migrants. The authors note that these migrants find it difficult to gain access to migratory regularization, much less to their self-perceived gender identity, while they are overrepresented among the victims of hate crimes and in criminal and prison statistics.

In short, the reviewed bibliography confirms that the analysis of the global migration control and border regime should not lose sight of the fact that the mechanisms that compose it affect men and women (cis and trans) and other sex-gender identities of the Global South in a differential way. Based on these findings, this article intends to contribute to the knowledge of the economy of expulsability for the Argentine case from a gender perspective.

The production of expulsability in Argentina (2010-2020). Contributions through the prism of gender

In the Argentine context, migration policies have undergone significant variations throughout history (Domenech & Pereira, 2017; Novick, 2008), which exceed the purposes of this article. Nevertheless, before analyzing the three state tools chosen, it was deemed necessary to point out that the period analyzed is framed within the Migration Law 25.871/2004 enacted during the presidency of Néstor Kirchner.14 Argentina’s most ambitious migration regularization program, Patria Grande, was also implemented during those years.15

However, from 2010 onwards, hateful expressions began to gain ground in the public discourse around migration, enunciated by politicians and media aligned with Mauricio Macri, who at that time was head of government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (Canelo et al., 2018). Subsequently, in 2012 during the presidency of Cristina Fernández, the arrival of Sergio Berni in the Secretariat of Security of the national government also contributed to the dissemination of discriminatory statements toward migrants by associating them with the growth of crime, and to the exaltation of the importance of controlling the borders and fostering a more selective entry of foreigners into the country.

The arrival of Mauricio Macri in the presidency led to setbacks in terms of the rights of the migrant population in the framework of the materialization of a national-security perspective based on the migration-illegality-crime-insecurity association (Canelo et al., 2018; Jaramillo et al., 2020; Penchaszadeh & García, 2018). Changes in the regulations described in the following sections were promoted, which operated as tools for producing and reproducing migratory irregularity. These measures make up what Domenech (2020, p. 2) has called the “politics of hostility”, which has increased the number of arrests, rejections at the border, and expulsable migrants.

The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the beginning of Alberto Fernández’s presidency. During this period, many migrants were left unprotected due to the lack of documentation they had carried over from previous years. In addition, public agencies remained closed, including the DNM, which made it difficult to carry out migratory procedures. Likewise, many measures taken by Macri remained in force during 2020, while the prolonged closure of borders affected family reunification and returns to the places of origin.

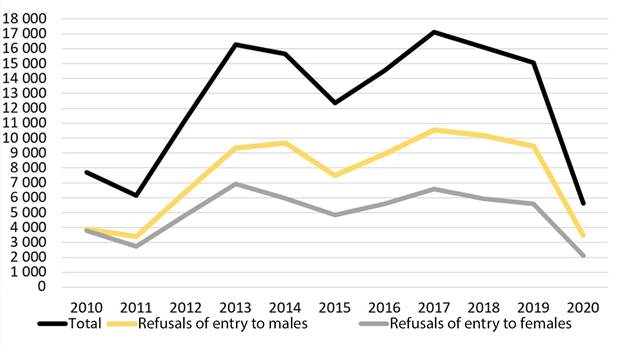

Refusals of entry to Argentina

Between 2010 and 2020, slightly more than 148 million applications by foreigners to enter Argentina were accepted, of which 55% were submitted by male,16 with differences according to nationality. During the same period, around 138 000 entry procedures were rejected. More specifically, the black line in Figure 1 indicates that rejections were relatively lower at the beginning of the period, but between 2012 and 2013 there was a significant increase, from around 11 000 to 16 000 (44%). Although an occasional decrease was recorded in 2015, until 2019 rejections remained high, with a peak in 2017 exceeding 17 000 cases. As expected, given the pandemic and the measures taken to close the borders, in 2020 there were fewer rejections, as fewer people attempted to enter the country.

Source: created by the authors based on special tabulations provided by the National Direction of Migration of Argentina

Figure 1 Refusals of entry based on sex registered of the person involved in the procedure (absolute values); Argentina, 2010 to 2020

The increase in refusals of entry since 2012 coincides with the implementation of the Integrated System of Migration Records (Sicam, by its acronim from spanish Sistema Integral de Captura Migratoria)17 of the DNM, which aims to monitor the entry and exit of people from Argentine territory using biometric patterns. Thus, “the old manual filling in of the Entry and Exit Card was replaced by the taking of a digital photograph, digital collection of fingerprints and scanning of the travel document to record the patronymic data” (Santi Pereyra, 2018, p. 259). In this context, the Federal Program of Collaboration and Assistance for Security, created in August 2013 and promoted by the Secretariat of Security during the government of Cristina Fernández, was also implemented. This program involved the deployment of more gendarmerie personnel on the borders, as well as the use of new technologies for border control.

The increase in rejections also coincides with the enactment of several DNM regulations. One is DNM Provision No. 899, which in 2013 established the procedure for the processing and payment of the exit clearance fee for all those foreigners who have irregularly stayed in the country with their stay or residency expired.18 Those who have not paid the fee are rejected in their attempt to return to Argentina.19 A year later, the DNM approved Provision No. 4362/2014, which established a new procedure for the resolution of suspect cases based on the “tourist” subcategory (Alvites Baiadera, 2018; Domenech, 2020). Likewise, in 2014 the DNM, the Federal Administration of Public Revenues (Administración Federal de Ingresos Públicos [AFIP]), the National Administration of Civil Aviation (Administración Nacional de Aviación Civil [ANAC]), and the Airport Security Police (Policía de Seguridad Aeroportuaria [PSA]) signed a joint resolution obliging international air transport service providers to submit in advance information regarding persons transported by air (both passengers and crew). Years later, during the government of Mauricio Macri, the DNM issued Memorandum No. 192/2018, which created the exclusionary category of “sensitive nationalities” that further hindered the entry of migrants of certain origins suspected of being “false tourists” (Gil Araujo & Jaramillo, in press). Shortly after that, the consular visa for Haitian nationals was regulated by Res. No. 477/2018 (Trabalón, 2021).

In short, the aforementioned regulations and actions constitute the framework for the increase in refusals of entry into Argentina. It is worth mentioning that they contribute to the increase in the number of people who enter Argentine territory through unauthorized channels and who will subsequently be prevented from obtaining a residence permit. Indirectly, these refusals of entry feed the growth of expulsion orders; in the same way, the latter affects future entries to the national territory.

On the other hand, considering the composition by gender, in every year there were more rejections of men than of women (Figure 1). In percentage terms, 60% of the rejections were of men during this period. Thus, and recalling what was stated at the beginning of this section, it can be seen that the percentage of refusals of entry for men is slightly higher than the percentage of entries approved for them.

An analysis of the annual variations shows that until 2013, rejections of men were below this average, at around 55%, so the gap with rejections to women was not so wide. On the other hand, in 2014 there was a relative increase in rejections of men that remained until 2020 at approximately 62%, reaching its highest values in recent years (2016-2020). Conversely, rejections of women went from representing 45% in the first four years of the study to 38% in the last seven years.

As for the reasons, according to information provided by the DNM, between 2010 and 2020 more than 60% of the rejections were motivated by the possession of unusable travel documents, while suspicion of false tourist status and the possession of outstanding debt have similar levels and together add up to about 30%. While the increase in male rejections is demonstrated for all reasons, it is most noticeable among those suspected of being false tourists. In fact, in the period studied, the relationship was reversed: in 2010 and 2011 there were more rejections directed at women motivated by the concept of false tourist (62%), but by 2012 rejections of males came to represent 60%, in 2016 they approached 80%, and afterwards they varied between 65% and 75%. It can be said, then, that the “false tourist” concept has been progressively masculinized in recent years.

Just as the refusals of entry are gendered, they are also concentrated in certain nationalities that are not always the most numerous. As Domenech (2020, p. 19) explains, “the accumulation of ‘border rejections’ is not the result of an individual or random practice. It is not a simple increase in the ‘flow of passengers’, but of travelers with certain national origins established in advance as suspicious”, subjected to processes of criminalization and racialization, and concomitant with border control regimes (Trabalón, 2021).

The nine nationalities shown in Figure 2 lead a long list and account for 91% of the refusals of entry between 2010 and 2020. Brazilian nationals are in first place with nearly 50 000 accumulated rejections, followed by Paraguayan nationals with just over 40 000. Except for Dominican nationals, where the majority of rejections have been of women (72%), the opposite is true for the rest, especially in the case of Peruvian and Colombian nationals, where around 80% of rejections are of men.

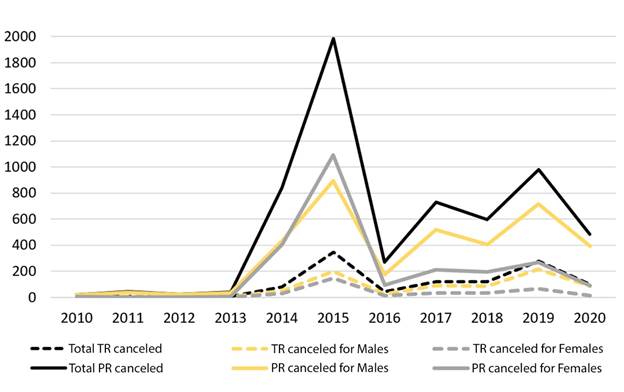

Residency cancellations

In the period covered in this article (2010-2020), about 1 300 000 applications for temporary residency and about 900 000 applications for permanent residency were registered.20 In the last years considered, a reduction in the number of residency applications submitted to the DNM has been recorded, especially permanent residency applications since 2016.

For the analysis presented below, it is also necessary to point out that temporary and permanent residency procedures initiated by men represented 54% and 46%, respectively, of the total number of applications. A similar composition by gender is found in the applications resolved by the DNM in both types. However, in the last years considered, it can be observed that, in relative terms, the number of applications initiated by men decreased moderately (between 2 and 3 percentage points) with respect to those initiated by women.

Regarding the central theme of this section, between 2010 and 2020 administrative cancellations of temporary and permanent residencies totaled 1 100 and 6 000, respectively. More specifically, between 2010 and 2013 both types of cancellations remained relatively low; however, in 2014 there was a significant increase in both, which was largely surpassed in 2015 with almost 2 000 permanent cases and 350 temporary cases (see Figure 3). Although cancellations decreased after that peak─which is exceptional in the years analyzed─they did not return to previous values. Instead, absolute values remained relatively high between 2017 and 2019, decreasing slightly in 2020 during the pandemic.

Source: created by the authors based on special tabulations provided by the National Direction of Migration of Argentina

Figure 3 Temporary residencies (TR) and permanent residencies (PR) canceled based on sex registered of the person involved in the procedure (absolute values); Argentina, 2010 to 2020

The increase recorded between 2014 and 2015 coincides with the approval of the protocol for digitizing files and the instructions for initiating digital procedures through DNM Provision No. 1/2014. This new technology allowed tighter control of the different “irregularities” hidden in the papers already stored on shelves for a long time. Thus, it became evident that many people had left Argentina, had remained outside the country for longer than the time stipulated by the Law, had overrun their residency, and so on.21

Later, between 2016 and 2019, the administration of Mauricio Macri exorbitantly increased the costs of the fees for migratory services and extended the waiting time to access an appointment to start procedures. Additionally, it closed the Territorial Approach Program (Programa de Abordaje Territorial), which implied the reduction of alternatives to access regularization and redoubled the “permanence controls” in public spaces generally identified with the presence of migrant population, among other actions (Jaramillo et al., 2020). However, the measure with the greatest repercussions was the Decree of Necessity and Urgency (DNU) 70/17─through which the executive branch modified the Migration Law No. 25.871 and the Nationality and Citizenship Law No. 346 without the intervention of the legislative branch─which expanded the grounds for the cancellation of residencies.22 Likewise, in 2018 the Foreigners’ Remote Settlement Module (Módulo de Radicación a Distancia de Extranjeros [RaDEx]) was put into operation and, at least during Macri’s government, did not fulfill the objective of facilitating the procedures for foreigners requiring residency in the Argentine Republic and changing their migratory category or subcategory, as well as applying for the National Identity Card (Documento de Identidad Nacional [DNI] ) and passport. Rather, it became an obstacle to regularization (Jaramillo et al., 2020).

In the period studied in this article (2010-2020), the number of procedures that the DNM directed at male migrants was significant: on average, seven out of every 10 cancellations of temporary residency and six out of every 10 permanent residency were directed at them (see Figure 3). However, it is interesting to note that during the 2015 peak, cancellations of permanent residency involved more female migrants than males. According to the migrant referents consulted, these were women who arrived in Argentina in the 1990s and early 2000s, mainly of Peruvian origin. In contrast, between 2017 and 2020, male residency cancellations increased significantly, reaching over 80% of these procedures in the last year.

Notably, the percentage of these residency cancellations involving men is higher than their applications for residency. Moreover, the relative “masculinization” of residency cancellations in recent years has occurred simultaneously with a moderate “feminization” of residency applications. These findings support the assumption that this state migration control tool is gendered.

In the period 2010-2020, it is interesting to note that 56% of the cancellations of temporary residencies and 61% of permanent residencies were motivated by irregularities in the times stipulated in subsection c) of Article 62 of Law No. 25.871, which after DNU 70/2017 was renamed as subsection d).23 Although the DNU did not modify the content of this subsection, the truth is that as of 2017 there was a relative increase in the number of cancellations of residencies, particularly those of males. More specifically, residency cancellations for males increased by seven percentage points in the case of temporary residency and five in the case of permanent residency on average, after the implementation of the decree mentioned above.

Finally, when the nationality dimension is incorporated into the analysis, it is found that the cancellations of temporary residency are mainly directed at Paraguayan, Chinese, and Bolivian individuals (each accounting for 20% of the procedures). Among permanent residency cancellations, those issued against Peruvian (32%) and Paraguayan nationals (16%) stand out. The procedures initiated against Paraguayan, Bolivian, and Chilean persons involve more males than those against Peruvians and Colombians.

Expulsion orders

Expulsion orders here analized are administrative proceedings initiated by the DNM, which can then be prosecuted. If this proceeds, a detention order may be issued and, finally, the expulsion of the migrant may materialize. Both residency cancellations and administrative expulsion orders express the threat of (at any moment) being separated from family and emotional ties built in the country of destination, losing one’s livelihood (and the ability to support others) and returning to a country that may have already been left behind, among other consequences. In particular, the expulsion order exposes the person to a kind of torment that can last for many years amid costly and entangled bureaucratic procedures.

Between 2010 and 2020, around 30 000 administrative expulsion orders were issued in Argentina. As can be seen in the black line in Figure 4, although in the first years the annual totals oscillated around 1 000 cases, in 2014 and 2015 they were approaching 2 000 cases per year, while in 2016 and 2017 there were around 4 500 cases per year, and the highest figures were observed in 2018 and 2019, with around 5 000 cases per year. In 2020, despite the pandemic, many administrative expulsion orders were recorded, exceeding the pre-Macri government’s figures.

This trend shows an increase in the expulsable population in the context mentioned, i.e., the incorporation of new technologies for the control of entry into the country, the digitalization of migration files and procedures, the approval of regulations that placed more conditions on entry into the country in 2013 and 2014, and the subsequent measures taken by the Macri administration. Particularly, DNU 70 of 2017 affected the grounds and procedures for expulsability so that migrants could be expelled without any proven crime, merely on suspicion, or for crimes with very low penalties. Moreover, in certain cases, expulsion could be carried out before a final sentence was handed down. For Domenech (2020, p. 12), DNU 70/17 “constituted the most significant act of the deportation policy that was taking shape and hegemonized the symbolization of the criminalization of migration”.

Source: created by the authors based on special tabulations provided by the National Direction of Migration of Argentina

Figure 4 Administrative expulsion orders based on sex registered of the person involved in the procedure (absolute values); Argentina, 2010 to 2020

Figure 4 also shows that over the period studied about three-quarters of administrative expulsion orders were against males. These orders are not only higher than those against females but also experienced a more pronounced absolute growth over the years. On average, between 2010 and 2011, 35% of expulsion orders were against females and 65% against males. However, from 2012 onwards, 75% of these orders were against males, reaching the highest percentage (77%) in 2020. It is worth noting that in these orders there is a significantly higher percentage of males than that found in the two indicators analyzed above.

Between 2010 and 2020, 80% of the administrative expulsion orders were aimed at the six nationalities shown in Figure 5, among which Chinese (close to 7 000) and Paraguayan nationals (around 5 000) stand out. It should also be noted that, except for Dominican nationals, the rest are over-represented in male holders, with Colombian and Peruvian nationals standing out.

Source: created by the authors based on special tabulations provided by the National Direction of Migration of Argentina

Figure 5 Administrative expulsion orders by nationality based on sex registered of the person involved in the procedure (absolute values). Argentina, 2010 to 2020

Most of these provisions (62%) were motivated by warnings─permanence control (Article 29 of Law No. 25,871). Like the rest of the motives, this one is also masculinized. However, when comparing the absolute values of the first three years studied (2010-2012) with the last three prior to the pandemic (2017-2019), it is found that proceedings against women multiplied 86 times, while those against men did so 59 times. That is, concerning this motive specifically, although the number of orders initiated by the DNM against males continues to be more significant, the rapid increase in proceedings against females should not be overlooked.

Finally, it should be noted that the expulsion orders analyzed in this section show much higher absolute values and growth than the number of expulsions carried out. The latter remained at an average of 320 per year between 2010 and 2016, began to grow after DNU 70/17, and reached 1 247 cases in 2019. Specifically in 2020, 490 expulsions were recorded: 373 were of males and 117 were of females. That is, 76% of the expulsions were of men, which is consistent with the trend followed by the expulsion orders analyzed above.

Final considerations

The preceding pages analyzed, from a gender perspective, the evolution of three tools of the Argentine State which, based on the analytical framework developed, are understood as belonging to the expulsability dimension: refusals of entry, cancellations of residency, and administrative expulsion orders, between 2010 and 2020. The methodological approach used descriptive statistics applied to data specially provided by the DNM for this article and the analysis of laws, decrees, and resolutions issued in those years.

In the historical context under analysis, four important junctures in Argentine politics left traces in the field of migration control. One of these, the years 2012-2013, is linked to the new provisions and control and security measures implemented by the government of Cristina Fernández, many of them in border areas. Then, around 2014-2015, the digitalization of files and procedures facilitated the cross-referencing of databases. Thus, technological change led to the deployment of more refined and comprehensive migration control. Between 2017 and 2019, obstacles to migration regularization imposed by the government of Mauricio Macri appeared, and the criminalization of migrants culminated in DNU 70/2017.24 Finally, the last year considered, 2020, corresponds to the measures taken by the government of Alberto Fernández in the face of the pandemic.

Even though not every law produces immediate or necessary impacts on official statistics, it can be said that the accumulated set of regulations leaves its mark on the evolution of official records over time. Between 2010 and 2020 there is a certain congruence between the progressive sanctioning of security-based regulations, practices, and discourses (including obstacles to migratory regularization) and the evolution of refusals of entry, residency cancellations, and expulsion orders. The latter not only gradually increased in volume but also became relatively more masculinized, especially in administrative expulsion orders. That is to say, although from the beginning of the period the procedures issued by the DNM to men were more severe than those issued to women, this process became more pronounced over time. A clear expression of this process can be seen in the refusals of entry motivated by the concept of the false tourist. Therefore, it can be said that the legal and administrative framework deployed during this period, which also carried over the consequences of state practices from previous years, had a specific impact on the construction of the expulsability of male migrants, even when they were not explicitly defined as targets in the regulations. It was also found that the volume of refusals of entry, cancellations of residency, and expulsion orders, as well as the importance of their masculinization, varied according to nationality.

Of course, the following questions arise: why is there a preponderance of procedures associated with men in refusals of entry and cancellations of residency, but especially in expulsion orders and actual expulsions? Why does this male preponderance vary according to nationality? These are questions that will be further explored in the future. However, based on Domenech (2020), it may be understood that the accumulation of these procedures is not the result of an individual or random practice. The findings indicate an economy of expulsability that, as critical studies have shown, is shaped by dynamics and ideologies of race, social class, and national origin, but also by gender dimensions, in accordance with what was revealed by the pioneering researchers (women, by the way) who inspired this article. For this reason, it is necessary to analyze the field of illegality and expulsability from an intersectional and situated perspective, which addresses the specific way in which the different axes of inequality (migratory status, nationality, gender, class, age, sexual orientation, among others) interact in the framework of the various rationalities, policies, and technologies that shape the illegalization of men, women (cis and trans), and other sex-gender identifications.

On the other hand, the documentary study corroborated the strengthening of control tools that make up the field of expulsion/expulsability, in addition to the three analyzed on this occasion. Among these are the extension of the use of the concept of the false tourist, the reinforcement of internal controls, the use of new technologies and databases, and the stricter requirements and greater difficulties in accessing documentation. These findings help confirm that the globalization of migratory control also involves South America. At the same time, they reaffirm the potential of the conceptual “toolbox” of the migration and border regime for the study of the field of migration control in the region. This is a general framework within which to study specific cases, which will lead to advances in the comparative work and the updating of the characterization of the South American migration and border regime.

Finally, future areas of study that emerge from this work may be proposed. A promising inquiry could involve the representations of state agents, security forces, and the justice system regarding male migrants of certain nationalities compared to the perceptions constructed around women. This would make it possible to explore the relationship between the contents of these ideologies and the configuration of a misandric, xenophobic, and racist profile. Another area that in the South American context has few precedents from a gender perspective is the intersection between migration and criminal policies and practices, bearing in mind that these use a binary gender approach that especially affects transgender people. It would also be useful to analyze the role of international organizations (UN, OIM, ACNUR) in the gendered construction of global control and border regimes, as well as the forms of resistance deployed in the framework of migrant struggles. On the other hand, although migration regularization is a central aspect of the migration and border control regime, there has been little analysis of its gender dimension in the regional context.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their suggestions and Eduardo Domenech for his generous reading of a preliminary version of this article.

REFERENCES

Álvarez Velasco, S. (2020). Ilegalizados en Ecuador, el país de la “ciudadanía universal”. Sociologías, 22(54), 138-170. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-101815 [ Links ]

Alvites Baiadera, A. (2018). Extranjeros bajo la lupa: la figura del “falso turista” en Argentina. Horizontes Decoloniales, (4), 39-62. https://doi.org/10.13169/decohori.4.0039 [ Links ]

Block, L. (2019). ‘(Im-)proper’ members with ‘(im-)proper’ families? - Framing spousal migration policies in Germany. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(2), 379-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625132 [ Links ]

Bonjour, S. & De Hart, B. (2013). A proper wife, a proper marriage: constructions of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in Dutch family migration policy. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 20(1), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506812456459 [ Links ]

Calvelo, L. (2011). Viejos y nuevos asuntos en las estimaciones de la migración internacional en América Latina y El Caribe (Serie Población y Desarrollo núm. 98). Naciones Unidas. http://hdl.handle.net/11362/7131 [ Links ]

Canelo, B., Gavazzo, N. & Nejamkis, L. (2018). Nuevas (viejas) políticas migratorias en la Argentina del cambio. Si somos americanos. Revista de Estudios Transfronterizos, 18(1), 150-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0719-09482018000100150 [ Links ]

Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS) & Comisión Argentina para Refugiados y Migrantes (Caref). (2020). Laberintos de papel. Desigualdad y regularización migratoria en América del Sur. https://www.cels.org.ar/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CELS_Migrantes_digital_Final-1.pdf [ Links ]

Clavijo, J. & Gil Araujo, S. (2021). Regímenes migratorios. En C. Jiménez Zunino & V. Trpin (Coords.), Pensar las migraciones contemporáneas. Categorías críticas para su abordaje (pp. 271-279). Editorial Tesseo. [ Links ]

Correa Álvarez, A. (2019). Deportación, tránsito y refugio. El caso de los cubanos de El Arbolito en Ecuador. Périplos, Revista de Investigación sobre Migraciones, 3(2), 52-88. https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/obmigra_periplos/article/download/30231/25627/67512 [ Links ]

Cravino, M. C. (2018). Política migratoria y erradicación de villas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires durante la última dictadura militar: la expulsión de migrantes de países limítrofes. Clepsidra. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios sobre Memoria, 5(10), 76-93. [ Links ]

De Genova, N. (2010). The deportation regime: sovereignty, space, and the freedom of movement. Theoretical overview. En N. De Genova & N. Peutz (Eds.), The deportation regime. Sovereignty, space, and the freedom of movement (pp. 33-65). Duke University Press. [ Links ]

______ (2019). Detention, deportation, and waiting: toward a theory of migrant detainability. Gender a výzkum/Gender and Research, 20(1), 92-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.13060/25706578.2019.20.1.464 [ Links ]

De Genova, N. & Roy, A. (2019). Practices of illegalisation. Antipode, 52(2), 352-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12602 [ Links ]

Domenech, E. (2015). Inmigración, anarquismo y deportación: la criminalización de los extranjeros “indeseables” en tiempos de las “grandes migraciones”. REMHU. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana, 23(45), 169-196. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-8585250319880004509 [ Links ]

______ (2017). Las políticas de migración en Sudamérica: elementos para el análisis crítico del control migratorio y fronterizo. Terceiro Milênio: Revista Crítica de Sociologia e Política, 8(1). https://www.revistaterceiromilenio.uenf.br/index.php/rtm/article/view/2 [ Links ]

______ (2020). La “política de la hostilidad” en Argentina: detención, expulsión y rechazo en frontera. Estudios Fronterizos, 21, Artículo e057. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2015057 [ Links ]

Domenech, E. & Dias, G. (2020). Regimes de fronteira e “ilegalidade” migrante na América Latina e no Caribe. Sociologias, 22(55), 40-73. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-108928 [ Links ]

Domenech, E. & Pereira, A. (2017). Estudios migratorios e investigación académica sobre las políticas de migraciones internacionales en Argentina. Íconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (58), 83-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.17141/iconos.58.2017.2487 [ Links ]

Dufraix Tapia, R., Ramos Rodríguez, R., & Quinteros Rojas, D. (2020). “Ordenar la casa”: securitización y producción de irregularidad en el norte de Chile. Sociologías, 22(55), 172-196. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-105689 [ Links ]

Duvell, F. (2015, 30 de septiembre). The globalization of migration control. Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/globalisation-of-migration-control/ [ Links ]

Fassin, D. (2011). Policing borders, producing boundaries. The governmentality of immigration in dark times. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 213-226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145847 [ Links ]

Fernández Bessa, C. (2019). La brecha de género en el dispositivo de deportación en España. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, (122), 85-109. doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2019.122.2.85 [ Links ]

Fleet, K. (1996). Situación de los inmigrantes y derechos humanos. En Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (Comp.), Informe Anual 1996 (pp. 261-288). https://www.cels.org.ar/web/wp-content/uploads/1997/10/IA1996-6-Situacion-de-los-inmigrantes-y-DD.HH_.pdf [ Links ]

Gil Araujo, S. (2005). Muros alrededor de “El Muro”. Prácticas y discursos en torno a la inmigración en el proceso de construcción de la política migratoria comunitaria. En M. T. Martin Palomo, M. J. Miranda López & C. Vega Solís (Eds.), Delitos y fronteras. mujeres extranjeras en prisión (pp. 113-137). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

______ (2011). Reinventing Europe’s borders: delocalization and externalization of EU Migration control through the involvement of third countries. En M. Baumann, A. Lorenz & K. Rosenow (Eds.), Crossing and controlling borders. Immigration policies and their impact on migrants’ journeys (pp. 21-44). Budrich Unipress. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvhhhh01.4 [ Links ]

Gil Araujo, S. & Jaramillo, V. (en prensa). Nacionalidades sensibles y proyectos migratorios. Travesías precarias de la migración colombiana en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Revista electrónica Temas de Antropología y Migración, (12). [ Links ]

Gil Araujo, S., Rosas, C. & Baiocchi, M. L. (2022, 10 de junio). La dimensión de género del control migratorio. Revisión de antecedentes sobre los países europeos, Estados Unidos y América Latina [Ponencia presentada]. II Seminario Internacional sobre Migración y Género, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México. [ Links ]

Gil Araujo, S., Santi, S. & Jaramillo, V. (2017). Externalización del control migratorio y políticas de migración familiar en Europa: instrumentos para un gobierno deslocalizado de la migración. En J. Ramírez (Coord.), Migraciones, Estado y políticas. Cambios y continuidades en América del Sur (pp. 197-214). Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. [ Links ]

Golash-Boza, T. (2016). The parallels between mass incarceration and mass deportation: an intersectional analysis of state repression. Journal of World Systems Research, 22(2), 484-509. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2016.616 [ Links ]

Golash-Boza, T. & Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2013). Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: a gendered racial removal program. Latino Studies, 11(3), 271-292. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2013.14 [ Links ]

González, T., Gil Araujo, S. & Montañés, V. (2013). Política migratoria y derechos humanos en el Mediterráneo español. El impacto del control migratorio en los tránsitos de la migración africana hacia Europa. Revista de Derecho Migratorio y Extranjería, (33), 245-267. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Gómez, J. (2018). De víctimas de trata a madres entregadoras. Cuando la expectativa de rol esperado conduce a la sospecha del delito. En M. J. Magliano (Comp.), Entre márgenes, intersticios e intersecciones. Diálogos posibles y desafíos pendientes entre género y migraciones (pp. 283-314). Editorial Teseo. [ Links ]

Herrera, G. & Berg, U. (2019). ‘Migration crises’ and humanitarianism in Latin America: the case of Ecuador. En N. N. Sorensen & S. Plambech (Eds.), Global perspectives on humanitarianism. (pp. 32-49). Danish Institute for International Studies. https://www.academia.edu/41756222/GLOBAL_PERSPECTIVES_ON_HUMANITARIANISM_3 [ Links ]

Hess, S. (2010). De-naturalising transit migration. Theory and methods of an ethnographic regime analysis. Population, Space and Place, 18(4), 428-440. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.632 [ Links ]

______ (2013). How gendered is the European migration regime? A feminist analysis of the anti-trafficking apparatus. Ethnologia Europaea. eJournal of European Ethnology, 42(2), 51-68. https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.1097 [ Links ]

Jaramillo, V., Gil-Araujo, S. & Rosas, C. (2020). Control migratorio y producción de irregularidad. Normas, prácticas y discursos sobre la migración en la Argentina (2016-2019). Forum. Revista del Departamento de Ciencia Política, (18), 64-90. https://doi.org/10.15446/frdcp.n18.81267 [ Links ]

Jaramillo, V. & Rosas, C. (2022). Sabrina sin DNI. Migrantes transgénero y control migratorio en Argentina. En C. Galaz, F. Stang & A. Lara (Eds.), El cruce polifónico de fronteras: Violencias y resistencias de personas migrantes LGTBI+ en Chile. Le Monde Diplomatique/Editorial Aún Creemos en los Sueños [ Links ]

Jarrín Morán, A. (2018). Deportados de España: Deportabilidad, expulsión y reasentamiento en origen de los inmigrantes ecuatorianos deportados de España [Tesis doctoral, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona]. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=272965 [ Links ]

Kofman, E. (2018). Family migration as a class matter. International Migration, 56(4), 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12433 [ Links ]

Koppman, Walter L. (2022). Aproximaciones para un análisis sobre la clase trabajadora judía de Buenos Aires en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, 1905-1930. Periplos. Revista de Investigación sobre Migraciones, 6(1), 17-39. https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/obmigra_periplos/article/download/42677/32895/126878 [ Links ]

Luibhéid, E. (2005). Introduction. Queering migration and citizenship. En E. Luibhéid & L. Jr. Cantú (Eds.), Queer migrations: sexuality, US citizenship, and border crossings (pp. ix-xlvi). University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Luibhéid, E. & Chávez, K. R. (Eds.). (2020). Queer and trans migrations: dynamics of illegalization, detention, and deportation. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctv180h78v [ Links ]

Magliano, M. J. & Clavijo, J. (2013). La OIM como trafficking solver para la región sudamericana: sentidos de las nuevas estrategias de control migratorio. En G. Karasik (Coord.), Migraciones Internacionales. Reflexiones y estudios sobre la movilidad territorial contemporánea (pp. 129-148). Ciccus Ediciones. [ Links ]

Magliano, M. J. & Domenech, E. E. (2008). Género, política y migración en la agenda global. Transformaciones recientes en la región sudamericana. En G. Herrera & J. Ramírez (Eds.), América Latina migrante: estado, familias, identidades (pp. 49-69). Flacso. https://n2t.net/ark:/13683/pazb/w4M [ Links ]

Menjívar, C., Gómez Cervantes, A., & Alvord, D. (2018). The expansion of “crimmigration,” mass detention, and deportation. Sociology Compass, 12(4), Artículo e12573. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12573 [ Links ]

Mezzadra, S. (2012). Capitalismo, migraciones y luchas sociales. La mirada de la autonomía. Nueva Sociedad, (237), 158-178. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/Nuevasociedad/2012/no237/11.pdf [ Links ]

Mole, R. C. M. (Ed.). (2021). Queer migration and asylum in Europe. UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv17ppc7d [ Links ]

Novick, S. (2008). Migración y políticas en Argentina: tres leyes para un país extenso (1876-2004). Clacso. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/iigg-uba/20190411022905/Novick8-8-08.pdf [ Links ]

Pedone, C., Agrela Romero, B. & Gil Araujo, S. (2012). Políticas públicas, migración y familia. Una mirada desde el género. Papers. Revista de Sociología, 97(3), 541-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v97n3.412 [ Links ]

Penchaszadeh, A. & García, L. E. (2018). Política migratoria y seguridad en Argentina hoy: ¿el paradigma de derechos humanos en jaque? URVIO, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad, (23), 91-109. https://doi.org/10.17141/urvio.23.2018.3554 [ Links ]

Piscitelli, A. & Lowenkron, L. (2015). Categorias em movimento: a gestão de vítimas do tráfico de pessoas na Espanha e no Brasil. Ciência e Cultura, 67(2), 35-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.21800/2317-66602015000200012 [ Links ]

Quinteros Rojas, D. (2016). ¿Nueva ‘crimigración’ o la vieja economía política del castigo? Dos aproximaciones criminológicas para entender el control punitivo de la migración en Chile. Astrolabio Nueva Época, (17), 81-113. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/astrolabio/article/view/16176 [ Links ]

Ramírez, J. (2018). De la era de la migración al siglo de la seguridad: el surgimiento de “políticas de control con rostro (in)humano”. Urvio, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad, (23), 10-28. https://doi.org/10.17141/urvio.23.2018.3745 [ Links ]

Rosas, C. (2010). Implicaciones mutuas entre el género y la migración. Mujeres y varones peruanos arribados a Buenos Aires entre 1990 y 2003. Eudeba. [ Links ]

Ruiz Muriel, M. C. & Álvarez Velasco, S. (2019). Excluir para proteger: la “guerra” contra la trata y el tráfico de migrantes y las nuevas lógicas de control migratorio en Ecuador. Estudios sociológicos, 37(111), 689-725. https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2019v37n111.1686 [ Links ]

Ruseishvili, S. & Chaves, J. (2020). Deportabilidade: um novo paradigma na política migratória brasileira? Plural, 27(1), 15-38. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2176-8099.pcso.2020.171526 [ Links ]

Santi, S. (2020). ¿Qué es la “migración ordenada”? Hacia el multilateralismo asimétrico como motor de las políticas de control migratorio global. Colombia Internacional, (104), 3-32. https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint104.2020.01 [ Links ]

Santi Pereyra, S. E. (2018). Biometría y vigilancia social en Sudamérica: Argentina como laboratorio regional de control migratorio. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 63(232), 247-268. https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2018.232.56580 [ Links ]

Sayad, A. (2008). Estado, nación e inmigración. El orden nacional ante el desafío de la inmigración. Apuntes de investigación, (13), 101-116. https://www.apuntescecyp.com.ar/index.php/apuntes/article/view/122 [ Links ]

Schrover, M. & Moloney, D. (2013). Conclusion. Gender, migration and cross-categorical research. En M. Schrover & D. M. Moloney (Eds.), Gender, migration and categorization. Making distinctions between migrants in Western countries, 1945-2010 (pp. 255-263). Amsterdam University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp7px.13 [ Links ]

Stang Alva, F., Lara Edwards, A. & Andrade Moreno, M. (2020, enero-junio). Retórica humanitaria y expulsabilidad: migrantes haitianos y gobernabilidad migratoria en Chile. Si Somos Americanos. Revista de Estudios Transfronterizos, 20(1), 176-201. https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/ssa/v20n1/0719-0948-ssa-20-01-176.pdf [ Links ]

Stang, M. F. & Stefoni, C. (2016). La microfísica de las fronteras. Criminalización, racialización y expulsabilidad de los migrantes colombianos en Antofagasta, Chile. Astrolabio Nueva Época, (17), 42-80. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/astrolabio/article/view/15781 [ Links ]

Trabalón, C. (2021). Racialización del control y nuevas migraciones: procesos de ilegalización durante la última década en Argentina. Periplos. Revista de investigación sobre migraciones, 5(1), 207-234. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/bitstream/handle/11336/152530/CONICET_Digital_Nro.09971929-5bcc-4654-8d1d-f4628f4c7656_A.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

1 The use of the notions of deportation and expulsion, among others, depends to a large extent on national legal frameworks, and in each case, they may express particularities that make it impossible to treat them as synonyms. In general, however, both notions refer to the action, attributable to a State, by which a migrant is forced to leave the territory of that State. For the purposes of this text, the notion of expulsion and its derivatives (expulsable, expulsability) is used because it is the one that corresponds to the legal framework of the case study, except when the cited source uses a different denomination.

2 It is known that the gendered nature of control is not limited to this aspect. Sustaining that the global migration control regime is gendered implies considering that all of its component practices are traversed by gendered constructions. For example, laws often incorporate gender stereotypes, institutionalizing perceptions that result in prejudice against specific groups of migrants (as in the case of laws that associate women migrants with certain jobs, which contributes to pigeonholing them in those jobs). On other occasions, policies appear to be “neutral” in terms of gender, but operate in a differentiated manner, since situations and specificities are not similar for the different sex-gender groups. State agents also imprint their gender biases in the daily treatment of migrants, as has been seen in the roadblocks targeting cis-males and transgender women. The same applies to the political and media discourses that make up the control regimes. In short, perceptions and stereotypes linked to the dominant gender constructions in transit and destination societies intervene in the way that the control of migrant populations assumes, always in intersection with the perceptions constructed around nationality, race, generation, social class, religious practices, and so on.

3 Argentina has a long tradition of migration in the southern region and has become the main destination for international south-south movements. Although at the time of writing this article the data corresponding to the 2022 national census have not been published, it is known that by 2010 international migrants accounted for 4.5% of the country’s total population. About 80% came from South American countries, particularly Paraguay, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. This was a slightly “feminized” migratory stock: women represented 54% of the total population born outside Argentina.

4 It should not be assumed a priori that the regulations are explanatory or causal elements of the evolution of the statistical data. Rather, the aim is to show the regulatory context in which variations in the data become visible.

5 The DNM did not provide the data corresponding to expulsions for the entire annual series considered, for which reason they are not included.

6 For purposes of clarity, when a preponderance of male or female holders is found in the procedures, the procedures will be referred to as “masculinized” or “feminized”, respectively.

7 Historically, administrative data have shown different limitations (Calvelo, 2011). For example, the year of registration of the data does not necessarily express the year of occurrence of the procedure in question. However, records have tended to improve after the implementation of the Integrated Migration Records System (Provision 843/2012).

9 It must be explained that the expulsions of foreigners perceived as “undesirable” are not new events. It is enough to mention for the Argentine case the expulsions of European migrants involved in the anarchist and workers’ movements (Domenech, 2015; Koppman, 2022), and those of border migrants (inhabitants of slums and settlements) during the last dictatorship (Cravino, 2018).

10 Golash- Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo (2013) state that most precedents in this field have not explicitly considered the intersectionality of gender with race and class in shaping the deportation regime.

11 Perhaps the most emblematic case of victimization of migrant women is what Hess (2013) calls the “anti-trafficking apparatus ”, which is especially aimed at controlling female migration, and which, according to the author, has become one of the pillars of the─restrictive and gendered─European migration and border regime.

12 Donald Trump, during his 2016 presidential campaign, declared that he intended to build a wall to keep out Mexican rapists (sic). Such rhetoric is not only anti-immigrant, but also places male migrants of Mexican origin in an invidious position, antagonistic to U.S. interests.

13 Examples of this are the various articles contained in the recent books edited by Luibhéid and Chávez (2020) and by Mole (2021).

14 This law was a major advance over the previous law, as it represented a substantial improvement in the migratory status and access to rights of migrants from Mercosur member and associated countries. However, it also institutionalized less favorable treatment for migrants from other countries. Likewise, securitizing components and an economics-based ideology persisted in the ways of understanding and legitimizing the migrant presence (Magliano & Domenech, 2008).

15 National Program of Migratory Documentary Standardization (Programa Nacional de Normalización Documentaria Migratoria) within the scope of the National Direction of Migration (Dirección Nacional de Migraciones) (Decree Nº 836/04; Decree Nº 578/05; Provision Nº 53253/05 and amendments).

16 These data do not include entries through unauthorized crossings, which would be interesting to analyze in the future from a gender perspective. It should also be considered that these procedures correspond not only to migrants, but also to tourists and other types of people traveling temporarily.

17 The regulation of Sicam (through Provision 843/2012) is linked to a series of previous regulations (Resolutions 0008/2005 and 12/2008, among others), associated in turn with the preceding Decree 836/2004. They declared the existence of an administrative emergency in the DNM and decreed the comprehensive evaluation of the operation of its offices throughout the national territory in order to homogenize procedures and establish uniform technical and administrative criteria.

19 “If, with a pending debt, the foreigner presents themselves to migration entry control, that foreigner will be rejected” (DNM, provision 899/2013).

20 In the same period, the DNM resolved approximately 1 255 000 temporary and 1 090 000 permanent permits.

21 The introduction of these technologies affected, for example, migrants from neighboring countries who had been granted residency through Decree 1033/92 (migratory amnesty) or who believed they had been granted residency. In other words, many of these people were unaware that their ID cards (DNI) had expired or believed they were permanent or had been swindled by false administrators and only possessed invalid documentation (Fleet, 1996). Something similar happened with the Peruvian population that, in the second half of the 1990s and early 2000s, had accessed different programs and agreements aimed at facilitating their regularization (Resolution No. 3850/94, Law No. 25099/99), in a context where arrivals from that country had increased and were feminized (Alvites, 2018; Rosas, 2010).

22 In short, DNU 70/2017─among other things─expanded the circumstances that allow the DNM to cancel residencies already granted and deny requested residencies or renewals, and established a summary expulsion procedure that generalizes the arrest of individuals and violates the right to official defense and access to justice. This DNU represented the blurring of the division between criminal and immigration law (Domenech, 2020).

23 This subsection stipulates that residency may be cancelled when The beneficiary of a permanent residency has remained outside the National Territory for a period exceeding two (2) years or half of the agreed term, in the case of temporary residency, unless the absence was due to the exercise of an Argentine public function or was due to activities, studies or research that in the opinion of the National Direction of Migration could be of interest or beneficial to the Argentine Republic or that there was an express authorization from the migration authorities, which may be requested through the Argentine consular authorities.

Received: December 20, 2021; Accepted: September 05, 2022

text in

text in