Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Universidad y ciencia

versão impressa ISSN 0186-2979

Universidad y ciencia vol.24 no.3 Villahermosa Dez. 2008

Artículos

Qualitative study of perceptions on poverty and present status of assets in a mayan community in the Yucatan Peninsula

Estudio cualitativo de percepciones sobre pobreza y estado actual de activos en una comunidad maya de la Península de Yucatán

Edgar Robles–Zavala1* y Tara Fiechter–Russo2

1 Instituto de Recursos. Universidad del Mar, Campus Puerto Ángel. Cd. Universitaria s/n San Pedro Pochutla, 70902 Oaxaca, México.(ERZ) *Correo electrónico: erobles@angel.umar.mx

2 Columbia University. Barnard College. Department of Environmental Sciences. (TFR)

Recibido: 27 de agosto de 2007

Aceptado: 30 de junio de 2008

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is two fold. First, it explores the local discourse about poverty in a highly marginalized municipality in the state of Yucatan, Mexico. Second, the study examines the present status of assets of 90 households through qualitative and quantitative techniques. The assessment was carried out using the Sustainable Livelihood Approach. The study concluded that the conditions of poverty in the households are closely linked to institutional factors, rather than to economic factors. The most severe constraints observed in the homes of the community were the low productivity of the milpa system, the lack of livestock, a food deficit, low social capital, corruption and incorrect public policies. These problems may be addressed by a combination of local participatory policies focussed on the solution of the multiple factors that determine the poverty and marginalization in the community.

Key words: Poverty perceptions, assets, mayas, humid tropics, Yucatan.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio tiene dos propósitos principales. En primer lugar, explora los discursos locales sobre pobreza en un municipio altamente marginado del estado de Yucatán, México. En segundo lugar, el estudio examina el estado actual de los activos en 90 hogares a través de técnicas cualitativas y cuantitativas. La evaluación se llevó a cabo a partir del Enfoque de Medios de Vida Sustentables. Se concluyó que las condiciones de pobreza en los hogares están estrechamente relacionadas con factores institucionales, más que de tipo económico. Las limitantes de mayor importancia que enfrentan los hogares de la comunidad fueron la baja productividad del sistema de milpa, falta de animales de corral, déficit alimentario, bajo capital social, corrupción, y políticas públicas incorrectas. Estos problemas podrán ser resueltos a través de una combinación de políticas participativas a nivel local, enfocadas a la solución de los múltiples contextos que determinan la pobreza y marginación en la comunidad.

Palabras clave: Percepciones de pobreza, activos, mayas, trópico húmedo, Yucatán.

INTRODUCTION

Historically, indigenous communities in Latin American countries have remained at the margins of development policies. Political discourse rhetorically holds these communities up as historical legacies of the nation, and as important pillars of the culture and national values. However, in practice, this discourse has demonstrated a lack of commitment to these groups, not only on the part of the government, but also on the part of particular sectors of society that discriminate and exclude them (Plant 1998).

The Mayas in the Yucatan Peninsula are not an exception to this socio–political situation. If political discourse vindicates the great historical legacy of these groups, why then do poverty, malnutrition, discrimination, a lack of voice in civil society and ignored human rights persist in these communities? The answer is closely related to the epistemological roots from which poverty alleviation strategies emerge. For decades, the study of poverty in Mexico has been enveloped in the positivist paradigm, in wich the poor are only a statistic, a number, an object rather than a subject which is embedded in social, cultural, political and historical contexts (Yapa 1996). Under this paradigm, the condition of poverty is defined solely based on income, and on whether or not expenses for health, education, food and housing can be met. The socio–cultural, historical and institutional circumstances around the poor have been largely ignored. While the hegemonic epistemic communities in Mexico have been discussing the contradictory outcomes of empirical data, as well as the most suitable methods to measure poverty, international agencies and research institutions have advocated to shift the epistemological paradigm of poverty reduction strategies to seriously consider the multidimensional character of poverty. Thus, this paper is set in the context of a larger development policy debate pertaining to poverty alleviation strategies in Mexico. Decades of poverty alleviation programs in Mexico have created communities that have become highly dependent on government support via cash transfers or palliatives through temporary job opportunities, as occurred in the most marginalized communities in the states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guerrero and Veracruz (Camacho & Hernández 2007). While current approaches have focused on the economic well being of households, the recently evolved Livelihoods Approach (Scoo–nes 1998; Carney 2002) reflects on the now accepted understanding that poverty itself is a complex, multidimensional situation that includes both material and non–material aspects of life (Anonymous 1997; Anonymous 2000a). The livelihood approach lays stress on livelihood assets, or capital, as the basis for the sustainable improvement of people's livelihoods. This is seen as a more effective reflection of development than income, as it indicates both the ability to accumulate wealth and the capabilities, or assets, that households can deploy to secure a living. The concept of livelihoods is increasingly being accepted as providing both a basis for understanding the nature of poverty, and for identifying the types of strategies that can reduce poverty in an effective and sustainable manner using different types of assets/capitals. Thus, this paper addresses the status of assets in a Maya community in Yucatan using the Livelihood Approach to emphasize the hidden contexts that affect the well–being of the people, which have been ignored for the purpose of public policies or development strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research framework. The asset or capital status

Recent academic and governmental discourses concerned with poverty alleviation reflect a growing awareness of the importance of a lack of assets as both a symptom and a cause of poverty (Londono & Szekely 1997; Baulch & Hoddinott 2000). They also recognize the value of the livelihood concept in understanding how the poor can call upon a range of different assets and activities as they seek to improve and sustain their well–being (Ellis 2000). Hence, the current view is that the survival strategies of the poor have been shaped by the quantity and quality of the assets or resources upon which they have depended. In this respect, successful asset accumulation is often observed to involve trading assets in sequence, for example, chickens to goats to cattle to land, or cash from non–farm income to farm inputs to higher farm income to land or to livestock (Ellis et al. 2003). Constructing such asset accumulation pathways has been critical for the achievement of rising prosperity over time (Bebbington 1999).

Therefore, this study adopted the Livelihoods Framework as the method to approach understanding of the circumstances, options and constraints of a Maya community. This approach has been discussed largely in the literature of development studies (Carney 1998; Scoones 1998; Ellis 2000; Toner & Franks 2006). However, while the framework does not aim to capture the complexity of poor people's livelihoods, it does try to provide a structure to think about and reflect on the causes of poverty. It assumes that poor people live with high levels of risk and vulnerability, and within this context their ability to access and use assets to produce beneficial livelihood outcomes is affected by the prevailing social, institutional and organizational environment.

The Livelihood Framework draws attention to five types of assets or capital upon which poor people's livelihoods depend: human, natural, financial, physical and social. Human capital refers to the labor available to the household in the form of education, skills and health that together enable people to pursue different livelihood strategies and achieve their livelihood objectives (Carney 2002). Natural capital comprises the land, water and biological resources that are used to generate means of survival (Ellis 2000). These natural assets provide goods and services, either without people's influence (e.g. forest wildlife, soil stabilization) or with their active intervention (e.g. farm crops, tree plantations, aqua–culture). Natural capital is important not only because of its environmental benefits, but also because it is the essential base of many rural economies (Scoones 1998). Physical assets include the capital that is created by economic production processes. Buildings, roads, transport, drinking water, electricity, communication systems, and equipment and machinery for producing further capital are examples of physical assets. Physical assets such as housing type, sanitation, sources of drinking water, and cooking and domestic appliances are commonly used as a proxy indicator of well–being. Improvements in physical assets measured over time are considered to be a sign of increasing well–being, as is for example the replacement of a thatched roof by a concrete one. Financial capital denotes the financial resources that people use to achieve their livelihood objectives (Anonymous 2000b). This definition is not economically robust in that it includes flows as well as stocks, and it can contribute to consumption as well as production. However, it has been adopted to try to capture an important livelihood building block, namely the availability of cash or the equivalent that enables people to adopt different livelihood strategies. Access to informal sources of credit is a valued asset. Social capital consists of networks of social relationships that are characterized by norms of trust and reciprocity. It is these combined elements which are argued to sustain civil society and that enable people to act for mutual benefit (Loch–ner et al. 1999). It is the quality of social relationships between individuals that affects their capacity to address and resolve the common problems they face (Lin 2001). Social capital can be understood as a resource of collective action, which may lead to a broad range of outcomes.

Study area

Tahdziu county (20° 12' – 20° 15' N, 88° 51' – 88° 59' W) with 3 891 inhabitants, is approximately 180 km from Merida, the capital city of the state of Yucatan. The population is predominantly Maya, with 99 % of the people older than five being bilingual, speaking Maya and Spanish (Anonymous 2005a). The population is mostly young with about 70 % below 30 years of age. The economically active population (PEA) is 26.4%. The majority of the people are catholic (Anonymous 2005a).

The village has one medical center, eight elementary schools and one middle school. The government office responsible for social and rural development and for health has applied several programs and projects to improve the economic and social condition of the population, including the installation of roads and community infrastructure, options of alternative employment, and health programs focused on child nutrition and pregnancy (Anonymous 2005b). In spite of these efforts, poverty still persists in the community. According to the National Council of Population, the municipality has the highest levels of poverty and marginalization in the state (Anonymous 2005c). Some socio–demographic indicators of the community are summarized in Table 1.

Factors of history, geography and politics have combined to make poverty reduction among the Mayas an enormous challenge. The Mayas are integrated with regional and national markets in different degrees depending on a variety of factors. Their lives are changing as they become more integrated with the rest of society. New productive agricultural practices, migration, urbanization and new opportunities outside of agriculture are just a few of the things affecting Maya lives as they become more "Westernized" due to the expansion of state–sponsored economic development programs.

The Maya agricultural strategy traditionally involves diversification for risk reduction, with a loose division of labor by sex. Men generally plant milpas, manage apiaries, hunt and participate in commerce, while women typically cultivate houseyard gardens, care for small domestic animals, collect firewood and harvest wild plants for household remedies and condiments (Faust & Bilsborrow 2000). Unfortunately, these practices are being rapidly eroded by new market factors, government policies encouraging private ownership and exports, school curricula that devaluate traditional knowledge, television programs that glorify modernism, and a pervasive loss of traditional religious beliefs associated with conservation practices (Terán & Rasmussen 1994). The cultural roots have been influenced by a modern society that is imposing new customs and fashions that are attractive to the new Maya generations (Hos–tettler 2003; Leatherman & Goodman 2005). The traditional "hipil" is being replaced by jeans, and the traditional "huaraches" are being substituted by tennis shoes. Coca–Cola is an essential drink in the Maya diet. The acculturation process is increasing in the Maya communities.

Sampling design

A wealth ranking technique was used to identify the stratification of well–being in the community, as well as to explore the local discourses surrounding poverty and well–being. The wealth ranking followed Grandin (1988). It generated insight into the local conception of wealth and provided a separate classification of households in the communities.

Four wealth groups were identified, and acted as the sampling parameters for a stratified random sample. With a list of households from each wealth group, 20 households were randomly chosen from each of the well–off and middle categories, and 30 households were chosen from the poorest category, providing a total sample of 90 households. The decision to sample more households from the poor category had the effect of slightly biasing the overall village sample towards the lower end of the wealth spectrum, but allowed a more accurate assessment of the relative livelihood circumstances of the poorer members of the village society.

Data collection design and analysis

Fieldwork was carried out during June and August, 2003. A combination of qualitative and quantitative methods yields insights that are not obtained when using either type of method on its own (Chambers 1994). Participatory techniques were used to capture the discourses concerning the people's feelings about their living conditions and basic needs. The methods applied in the community were: (1) key informant interviews, (2) wealth ranking exercises, (3) participant observations of the daily internal and external routines and activities of selected households, (4) group discussions focused on young people, women, children and farmers, (5) mapping the distribution of wealth, (6) ranking preferences and priorities, and (7) calendars and time use diagrams for the seasonality of income sources and access to assets. In order to construct a Possession Score to assess household socioeconomic status, the households were questioned regarding the ownership of a checklist of 10 items (radio, television, video recorder, telephone, electric fan, sewing machine, refrigerator, gas or electric fire, bicycle, and car). The score ranged from 0 to 10. A survey was applied to provide quantitative information about the households. The principal variables studied were the indicators of each asset. This survey was implemented with an extensive questionnaire that was initially designed to obtain information on the following seven topics: demographic data, consumption and expenditure patterns, agricultural activity, health, housing, education and social capital. A Tukey HSD post–hoc test was used to compare the different variables among the wealth groups (Bryman & Cramer 1997).

RESULTS

Local concepts of poverty and well–being

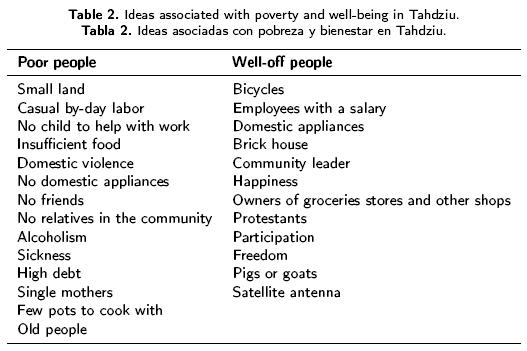

The following elements emerged during the wealth ranking exercise for the local characterization of poverty and well–being (Table 2):

Physical assets. These mainly included the type and condition of housing and domestic appliances. Domestic appliances also served the function of stores of wealth that could assist households to survive lean times and therefore reduce vulnerability to temporary crises. For example, a TV or radio could be offered in exchange of a loan.

Human assets. Labor as an important asset received constant emphasis in defining the poor, especially in the light of factors such as disability, age, health, childlessness and widowhood. Some of those affected by these factors included single mothers, the elderly (who could no longer work and lacked networks of kin support), and sick people. Children as a labor input was a critical asset in the community, whereas education was never mentioned.

Social Assets. An individual's social status and network was an essential resource. To have friends or relatives generally conferred access to resources such as income in cash for emergencies or crises. Access to and control over labor was critically affected by an individual's social status (including gender) and position within the kin group. The "compadrazgo" was a key element of social capital in the community. The "compadrazgo" is a mutual kinship system which is sealed on any of three ceremonial occasions –baptism, confirmation and marriage–. It dates back at least to the introduction of Christianity and perhaps earlier (Berruecos 1976; Nutini 1984). It is a primary method of extending the group from which one can expect help in the way of favors such as jobs, loans or just simple gifts on special occasions. But in asking a friend to become godparent to a child, a Mexican is also asking that person to become a closer friend. Thus, it is common to ask acquaintances who are of higher economic or social status than oneself to be sponsors. Such ritual kinship cannot be depended on in moments of crisis to the same extent as real kinship, but it still works for small and regular acts of support, such as gift giving. Isolation from kin networks was an element of social marginalization for many groups.

Activities. Fixed employment with a salary was seen as an indicator of wealth in the community. In contrast, the need to engage in casual 'by–day' labor was seen as an indicator of being poor because 'by–day' labor is highly vulnerable. It provides supplemental employment opportunities in times of seasonal change, low agricultural production and economic stagnation.

Level of consumption. With respect to consumption, secure access to income and food dominated the discussion. Emphasis on the diversity of the diet as well as absolute access to food was frequently an indicator of wealth. However, high quality diets were not a topic in the group discussions. In the survey applied, the consumption of 'junk' food and carbonated beverages was widely spread in all the wealth groups. Coca–Cola was preferred to milk in many households.

Intra–household dynamics. Domestic violence, alcoholism and drug addiction are increasing in the community. The problems associated with these phenomena have created insecurity and tension within households.

Subjective claims. Concepts such as happiness, freedom and participation emerged from the group discussions as characteristics of well–being. These aspects have been largely ignored in all poverty alleviation programs.

Once the local concept of poverty and wealth were discussed, the participants in the wealth ranking exercise identified four wealth groups and their characteristics (Table 3). Again, the word "happiness" is associated with the rich wealth group. The lack of labor capability through means of production was an indicator that identified the lowest wealth stratum. Almost 60% of the households live in poverty, and only 10% were considered rich in the village (Table 3).

The dimensions of poverty through the eyes of women and men were quite different (Table 4). For women, intra–household dynamics is a key issue in determining well–being. For men, the wealth received from labor is the standard for well–being. The notable differences in perceptions of men and women about the root causes of their poverty were mainly related to the differences in livelihood–related activities and culture–specific norms governing the lives of men and women. Men associate poverty with production issues, such as the low productivity of their agricultural system, and with the lack of government support. On the contrary, women associate poverty with issues that concern family dynamics, such as violence, drugs or food insecurity. Also, they are concerned with the migration of men to the U.S. looking for work.

Asset status

The poorest and poor wealth groups were statistically similar (HSD; p > 0.5) in terms of land, livestock, milpa productivity, household possession, monthly income, and energy intake. However, the values of these two groups were significantly different (HSD; p < 0.05) from those of the middle and rich wealth groups. The rich group was significantly different (HSD; p < 0.05) from the other three groups in terms of land, livestock, household possessions and income (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Local concepts of poverty and well–being

The concepts expressed by the people regarding poverty and well–being are similar to those produced using participatory techniques, where the voice of the people has been rescued (Narayan et al. 2000a; Narayan et al. 2000b; Begajo 2004; Baker–Collins 2005). In a pattern similar to those in the cited studies, the Mayas of Tahdziu associate poverty or well–being not only with income per se. Assets such as land size, number and type of live–stock, food security and diversity of farm products were predominantly used to differentiate the poor and the non–poor. The institutional context, the family dynamics and the social networks also played a key role in the perceptions of poverty and well–being. Similar findings were observed during the Participatory Poverty Assessments carried out by the World Bank in Latin American countries included Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, that harbour important indigenous communities (Anonymous 2007).

In Mexico, the Ministry of Social Development carried out an extensive study with the aim to listen to the needs and concerns expressed by poor communities (Hernández–Licona & del Razo Martínez 2004). However, the study followed the traditional view of the Mexican government on how to study poverty. Instead of applying a set of qualitative and participatory techniques to record the concerns of the poor, the study applied statistical analyses (Propensity Score Matches) to analyze the perception of the people regarding social programs. The voice of the people is in the hands of the econometrics.

In the context of Mayan culture, the term better–off is relative and does not necessarily signify wealth or income status much above the poverty line. As revealed by the wealth ranking exercises conducted in the community, households described as well–off are distinguished by having landholdings of more than 2.4 ha and fixed employment, hiring non–family labor seasonally, owning non–farm services sector businesses, and normally enjoying year round food security. The middle wealth categories have correspondingly less of all these assets, and worsening seasonal food security. The poorest possess little or no land, few small livestock, rely on casual work or safety net transfers to get by, and are in a food deficit most of the year. These findings are similar to those reported by Daltabuit (1992) for the community of Yalcoba, Yucatan, where an indicator of socioeconomic status was used and two different groups were identified (a low and a high stratum). Households in the low stratum had a small piece of land for agricultural activities, and few livestock. The high stratum had larger land, livestock and small businesses such as groceries stores. Investigating the experience and understanding the poverty in the community involved not only looking at how people defined those conditions, but also at how they saw the distribution wihtin those categories. From their own words: (1) "The richest are those that have a salary and do not depend on the milpa (man, 37 years old)". This statement emerged in reference to the presence of teachers and government officers who received a monthly salary, and therefore had secure livelihoods, and (2) "He is better off because he is a close friend of the Municipal President (man, 51 years old)". Social capital, as translated into relationships with powerful agents or authorities, provided a means of access to several benefits.

The members described above were simply referred to as "the rich" (and very few could be named in the community). At the other extreme were the chronically hungry, continuously referred to as the extremely poor. They are described by the following statements: (1) "Poverty means the lack of happiness. I mean, if you are unhappy with your family, with your community, with nature, you are poor (man, 58 years old)". The Mayas confer a particular meaning to poverty that is not related to material possessions. For many Mayas, poverty means a lack of internal stability associated with family and community problems, and is inclusive of the damage to their ecological surroundings, and (2) "You know, the heat is worse, the lack of rain lasts many months at a time, it is more difficult to obtain food from the milpa. All these issues mean poverty for us (woman, 62 years old)". This statement established the close relationship raised by the Mayas between poverty and nature.

Asset status

It is often suggested that access to assets enables poor people to develop their own pathways out of poverty (Moser 1998; Bebbington 1999; Ellis 2000). Other things being equal, households with an abundance of different assets are more able to cope with shocks and to exploit opportunities to accumulate wealth than those that have fewer assets.

Natural Assets

Land ownership data across wealth groups uncovered an expected finding: there was a significant difference between mean landholding in the sample (Table 5). When livestock holding was compared across wealth groups, a similar picture emerged of a large difference in livestock between the rich and the other wealth groups. Thus, land and livestock provide two distinct markers for success in Tahdziu. All livestock were converted into cattle equivalent units (CEUs). This was achieved by calculating market value ratios between the mean current prices of different species of livestock. The figures were as follows: cattle = 1, goats = 0.23, sheep = 0.25, pigs = 0.35, turkey = 0.15 and chickens = 0.13. The evidence for Tahdziu is similar to parallel findings for other countries (Ellis & Bahiigwa 2003, Ellis & ="2">Mdoe 2003). It is only the highest wealth group that displays a significantly different mean livestock ownership, in contrast to the other wealth groups. The livestock types recorded were goats, sheep, pigs, turkeys and chickens. The two most common livestock groups owned by households in the sample were turkeys and chickens. Pigs were the most common livestock among the wealthiest group.

The productivity of the milpa reflects the access to agricultural inputs. The middle and rich groups use fertilizers in their agricultural activities, whereas the other groups do not. Some concerns emerged during the focus groups: "The milpa is our subsistence activity, but it is insufficient. Years ago we obtained plenty of food from it, but now, it is not enough. There is not enough rain. Our land is too small to provide us with credit (man, 43 years old)".

There are divergent positions regarding the causes of the low productivity in the milpas. Some authors have argued that the traditional clearing practice of slash–and–burn has affected agricultural productivity (Terán & Rasmussen 1994). While many studies have criticized the Mayan slash and burn agricultural system (Eastmond & Faust 2006), the cultural and social contexts around this system have been largely ignored. Also, the policies of communal land tenure (ejido) have been considered as an important cause of soil deterioration (Daltabuit 1992). The fact is that the use of land for a growing population is causing additional pressure. Soil fertility is declining in many areas in the Yucatan Peninsula because population pressure has led to constant cultivation of the same land for many decades. It is important to emphasize that the activities around the milpa are not restricted to agricultural production. The milpa shapes the daily activities of all the members of the family, assuming the gender roles of work, care, cooking and so on. Likewise, the milpa has been responsible for a high percentage of the food security in the household. The life in all Mayan communities is ruled by the dynamics of the milpa (Bonfil–Batalla 1962; Terán & Rasmussen 1994).

Physical assets

The most frequent material possessions found in the poor and poorest groups were a TV and a radio. The importance of the TV in marginalized communities in Mexico has been emphasized in other studies (Robles–Zavala 2004, Naar & Robles–Zavala 2006). In the voice of the people: "To me, the TV is my way to escape from my reality. I can travel to different places and I forget the cries of my children (woman, 29 years old)", and "We can be very poor, but the TV is indispensable for us (woman, 42 years old)". This statement coincides with the role of the television as a source of subjective well–being in this society (Frey et al. 2007).

Financial assets

Monthly income presented important differences among the wealth groups in this survey. The income received by the poor and poorest groups is for casual by–day labor. The income portfolio for these groups is very narrow as a consequence of low employment opportunities in the region. They state their own condition in these words: "In the region there are no job opportunities. Many people have migrated to Cancun looking for a permanent job in building. Others have decided to go to the U.S. I stay here because I am old, but if I were young, I would migrate too (man, 64 years old)".

A very important asset in the community is the access to public transfer payments. "Oportunidades" has been the principal anti–poverty program of the Mexican government since 2000 (Szekely 2005). It focuses on helping poor families in rural and urban communities to invest in human capital. It improves the education, health and nutrition of their children by providing cash transfers to households that are linked to regular school attendance and health clinic visits.

According to Table 5, all wealth groups received transfers through "Oportunidades", including the rich group. For the poorest, the transfers constitute almost 50 % of their total income. The result has been the creation of a group that is highly dependant on government support and, consequently, tied to its will. "The mayor has told us that we must show gratitude for Oportunidades, and that we must remember to support him during the elections (man, 53 years old)".

Contrary to the expected outcomes, "Oportunidades" has not been the solution for child labor in Tahdziu, as to be involved in agriculture in early years is a custom that has been maintained for generations in this town. Now, "Oportunidades" has represented an additional source of income for the families, although labor outside the school remains the same. Women encounter the same situation. By custom, they have many responsibilities in the house and, in the absence of the mother, they assume the responsibility of preparing meals, cleaning and so on. "I registered my children in school because we need the money from "Oportunidades". However, they have the obligation to help me in the milpa, and the women have to help their mother in the house. If they want to go to school, they have to suffer for this education (man, 43 years old)". The results of cash transfers programs designed to prevent child labor have been contradictory. In a study for Latin America, Barrientos and de Jong (2006) found that cash transfers programs are an effective way to reduce child labor. However, the opposite outcome was recorded for rural communities in Colombia where child labor was unaffected by these programs (Attanasio et al. 2006).

Human asset

While the positive effects of education on the economic and social well–being of households worldwide are well documented in the literature (Psacha–ropoulos 1994), this relationship was not evident in this study (Table 5). The villagers offered reasons for the large population of uneducated individuals: There was no school in the village when they were young, and child labor was necessary for agricultural activities. For women, domestic duties were more critical. "When I was young, there was no school in the village. The nearest school was in Peto, so my parents preferred that I farm (an old man)". "School was never seen as a good opportunity for us. The need was in the milpa because the milpa is the traditional activity for us. You need to read and write, but the other things taught in school are useless (man, 56 years old)".

Obesity and malnutrition are present among children, teenagers and adults. The diet of the four wealth groups is rich in fats and contains high amounts of carbonated beverages.

The problem of malnutrition has been largely documented in Yucatan (Bonfil–Batalla 1962; Dalta–buit 1992; Anonymous 2005d). At the national level, Yucatan is at the top of the list of malnutrition in children under five years of age (Anonymous 2006). It is important that Mexicans consider the adoption of new eating habits, particularly the Mayas in Yucatan. The most evident example is that Coca–Cola is a common element in the Mayan diet, in addition to calorie–dense but nutrient–poor snack foods. The consequences of this diet, likely exacerbated by the increased consumption of snack foods, include an increase in overweight and obese adults, as well as signs of stunted growth in children (Anonymous 2005d).

Social Assets

Trust is closely related to social capital (Adler & Kwon 2000; Coleman 1988; Putnam 1993; Naha–piet & Ghoshal 1998). According to the survey, the level of trust on other members of the community is low in comparison with other similar studies (Lyon 2000, Sharp & Smith 2003, Yip et al. 2007). The villagers responded that theft of private assets like chickens, turkeys and pigs is increasing. Alcoholism and drug addiction is also creating a high vulnerability among social ties. Fights, social disorders and petty crime are increasing in the community.

Trust in the institutions presented two different perspectives. During the focus group discussions, members of the community identified differences between the image of the local and the external institutions. The local institutions included the local and state governments, whereas the external institutions were based on federal policies such as "Oportunidades", public policies for health promotion, or temporary employment. Trust in local institutions increases as wealth increases among the groups. The middle and rich groups have strong ties with the local government. In particular, the rich group locally constitutes an economic power. As a custom, the elected representatives in government emerge from these powerful groups, and are consequently linked to several economic interests. The poor and the poorest identified the high levels of corruption in the local government as a cause of marginalization in the community: "When hurricane Isidore hit here, the first beneficiaries with food and shelter were the closest friends of the mayor (man, 45 years old)".

Federal agencies and policies do not depend on local governments. Social development programs such as health promotion, temporary employment, management of natural resources, subsidies or credit programs for agricultural inputs are designed far way from the town. Oportunidades and health promotion were the most important institutions as ranked by the poor and poorest wealth groups. However, in the realization of other development projects, the first link between the decision–makers and the village is the local leaders. Unfortunately, government personnel have ignored the poor and their needs.

In spite of the efforts of state and federal programs to alleviate poverty in Tahdziu, the community has maintained the highest level of marginalization in Yucatan for decades.

The study described in this paper reinforces the precariousness of rural survival in Yucatan that has been emphasized by previous researchers. The majority of rural families confront severe constraints and have little room to maneuver, and the occurrence of shocks such as hurricanes and scarce rainfall quickly push them into requiring emergency food relief. These multiple constraints include small and declining farm sizes, lack of livestock as a bartering asset, deteriorating civil security in the community, prevalence even in normal years of food deficit from personal production, low monetization of the rural economy, little circulating cash, and institutional blockages to breaking out of established livelihood patterns.

At the level of the family or household, securing a better living standard is a cumulative process that requires an ability to build assets and diversify across farm and non–farm activities. In this process, cash generation is critical since it confers the capability to invest either in improved farm practices or in non–farm assets, or a combination of both, according to the options that arise to reduce risk and increase income generation. Likewise, the increasing social capital in the community is a core element for the purpose of public policies. No amount of school or road building in the community will reduce poverty if corruption practices are spread by local governments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is an outcome of the workshop "Socioeconomic Diagnosis of Rural Communities", that took place in the Universidad Marista de Merida, Yucatan. We are grateful to the members of our research team, Alejandra Silveira, Alejandra Bolio, Mariela Castilla, Liliana Salinas, Ana Aguilar, Marcela Landeros, Romina Marrufo, Guillermo Buenfil and Miguel Angel Vela for support during the field work. The views expressed do not represent those of the Universidad Marista de Mérida. The authors appreciate the constructive comments of three anonymous referees.

REFERENCES

Adler P, Kwon S (2000) Social capital: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In: Lesser EL (ed) Knowledge and social capital: Foundations and applications. Butterworth–Heinemann, Boston. 208 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (1997) Human Development Report. United Nations Development Program. Oxford University Press. New York. 134 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (2000a) World Development Report 2000/2001, Attacking Poverty. World Bank. Washington D.C. 352 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (2000b) Eliminating world poverty: Making globalisation work for the poor. Department for International Development. London. 108 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (2005a). II Conteo de Población y Vivienda 2005. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI) http://www.inegi.gob.mx [ Links ]

Anonymous (2005b) Quinto Informe de Gobierno. Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán http://www.yucatan.gob.mx [ Links ]

Anonymous (2005c) Indices de Marginación 2005. Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO). http://www.conapo.gob.mx [ Links ]

Anonymous (2005d) Encuesta Nacional de Alimentación y Nutrición en el Medio Rural. Estado de Yucatán. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. D.F. 48 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (2006) México ante los desafíos de desarrollo del milenio. Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO) D.F. 38 pp. [ Links ]

Anonymous (2007) Participatory Poverty Assessment in Latin America. http://www.worldbank.org [ Links ]

Attanasio O, Fitzsimons E, Gómez A, López D, Meghir C, Mesnard A (2006) Child education and work choices in the presence of a conditional cash transfer programme in rural Colombia. Working Paper. The Institute for Fiscal Studies. London. 35 pp. [ Links ]

Baulch B, Hoddinott J (2000) Special issue on economic mobility and poverty dynamics in developing countries. The Journal of Development Studies 36(6): 1–24. [ Links ]

Baker–Collins S (2005) An understanding of poverty from those who are poor. Action Research 3(1): 9–13. [ Links ]

Barrientos A, de Jong J (2006) Reducing child poverty with cash transfers: A sure thing? Development Policy Review 24(5): 537–552. [ Links ]

Bebbington A (1999) Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development 27(12): 2021–2044. [ Links ]

Begajo B (2004) Local perspectives on poverty and development. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on the Ethiopian Economy. Addis Ababa. 26 pp. [ Links ]

Berruecos L (1976) El Compadrazgo en América Latina; Análisis antropológico de 106 casos. México: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. Serie Antropología Social. D.F. 114 pp. [ Links ]

Bonfil–Batalla G (1962) Diagnóstico sobre el hambre en Sudzal, Yucatán: Un ensayo de antropología aplicada. CIESAS. D.F. 242 pp. [ Links ]

Bryman A, Cramer D (1997) Quantitative data analysis with SPSS for Windows. Rutledge. London. 318 pp. [ Links ]

Camacho Z, Hernández JC (2007) Morir en la pobreza. Revista Contralínea 5(75): 1–15. [ Links ]

Carney D (1998) Sustainable rural livelihoods: What contribution can we make? Department of International Development. London. 122 pp. [ Links ]

Carney D (2002) Sustainable livelihood approaches: Progress and possibilities for change. Department for International Development. London. 64 pp. [ Links ]

Chambers R (1994) The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development 22(7):953–969. [ Links ]

Coleman J (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: 95–120. [ Links ]

Daltabuit M (1992) Mujeres mayas: Trabajo, nutrición y fecundidad. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas. D.F. 238 pp. [ Links ]

Eastmond A, Faust B (2006) Farmers, fires and forests: A green alternative to shifting cultivation for conservation of the Maya forest? Landscape and Urban Planning 74(3): 267–284. [ Links ]

Ellis F (2000) Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 237 pp. [ Links ]

Ellis F, Bahiigwa G (2003) Rural livelihoods and poverty reduction in Uganda. World Development 31(6): 997–1013. [ Links ]

Ellis F, Mdoe N (2003) Rural livelihoods and poverty reduction in Tanzania. World Development 31(8):1367–1384. [ Links ]

Ellis F, Kutengule M, Nyasulu A (2003) Livelihoods and rural poverty reduction in Malawi. World Development 31(9): 1495–1510. [ Links ]

Faust B, Bilsborrow R (2000) Maya culture, population, and the environment on the Yucatan Peninsula. In: Lutz W, Prieto L and Sanderson W (eds) Population, Development and the Environment on the Yucatan Peninsula: From ancient Maya to 2030. IIASA, Laxenburg. 267 pp. [ Links ]

Frey BS, Benesch C, Stutzer A (2007) Does watching TV make us happy? Journal of Economic Psychology 28(3): 283–313. [ Links ]

Grandin BE (1988) Wealth ranking in smallholder communities: A Field manual. Intermediate Technology Publications. London. 60 pp. [ Links ]

Hernández–Licona G, del Razo–Martínez LM (2004) Lo que dicen los pobres: Evaluación del impacto de los programas sociales sobre la percepción de los beneficiarios. Serie Documentos de Investigación, SEDESOL. D.F. 44 pp. [ Links ]

Hostettler U (2003) New inequalities: Changing Maya economy and social life in central Quintana Roo, Mexico. Research in Economic Anthropology 22: 25–59. [ Links ]

Leatherman T, Goodman A (2005) Coca–colonization of diets in the Yucatan. Social Science and Medicine 61(4): 833–846. [ Links ]

Lin N (2001) Social capital: a theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 292 pp. [ Links ]

Lochner K, Kawachi I, Kennedy BP (1999) Social capital: a guide to its measurement. Health and Place 5:259–270. [ Links ]

Londono JL, Szekely M (1997) Persistent poverty and excess inequality: Latin–America 1970–1995. Working Paper 357. Inter–American Development Bank. Washington D.C. 71 pp. [ Links ]

Lyon F (2000) Trust, networks and norms: The creation of social capital in agricultural economies in Ghana. World Development 28(4): 663–681. [ Links ]

Moser C (1998) The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development 26(1): 1–19. [ Links ]

Naar N, Robles–Zavala E (2006) A pilot study identifying environmental health concerns and priorities in Puerto San Carlos, Mexico. SFS DR Report. Puerto San Carlos. 48 pp. [ Links ]

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 23(2): 242–266. [ Links ]

Narayan, D, Patel R, Schafft K, Rademacher A, Koch–Schulte S (2000a) Voices of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us? Oxford University Press. New York. 280 pp. [ Links ]

Narayan, D, Chambers R, Kaul Shah M, Petesch P (2000b) Voices of the Poor: Crying Out for Change. Oxford University Press. New York. 332 pp. [ Links ]

Nutini H (1984) Ritual Kinship: Ideological and Structural Integration of the Compadrazgo System in Rural Tlaxcala. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 520 pp. [ Links ]

Plant R (1998) Issues in indigenous poverty and development. Inter–American Development Bank. Washington D.C. 46 pp. [ Links ]

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Development 22(9):1325–1343. [ Links ]

Putnam R (1993) Making democracy work: Civic tradition in modern Italy. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 280 pp. [ Links ]

Robles–Zavala E (2004) Poverty in rural fishing communities. A view from the inside. PhD Thesis School for Development Studies. University of East Anglia. Norwich. 250 pp. [ Links ]

Scoones I (1998) Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper, No. 72. Institute of Development Studies. Sussex. 22 pp. [ Links ]

Sharp JS, Smith MB (2003) Social capital and farming at the rural–urban interface: The importance of nonfarmer and farmer relations. Agricultural Systems 76(3): 913–927. [ Links ]

Szekely M (2005) Pobreza y desigualdad en México entre 1950 y 2004. Serie Documentos de Investigación. SEDESOL. D.F. 34 pp. [ Links ]

Terán S, Rasmussen C (1994) La milpa de los Mayas. Editorial Fundación Tun Ben Kin, A.C. Mérida. 349 pp. [ Links ]

Toner A, Franks T (2006) Putting livelihood thinking into practice: implications for development management. Public Administration and Development 26: 81–92. [ Links ]

Yapa L (1996) What causes poverty? A postmodern view. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86(4): 707–728. [ Links ]

Yip W, Subramanian SV, Mitchell AD, Lee DTS, Wang J, Kawachi I (2007) Does social capital enhance health and wellbeing? Evidence from rural China. Social Science and Medicine 64(1): 35–49. [ Links ]