Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Contaduría y administración

versión impresa ISSN 0186-1042

Contad. Adm vol.65 no.2 Ciudad de México abr./jun. 2020 Epub 09-Dic-2020

https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2019.2069

Articles

The effects of institutional burdens on the entrepreneurship dichotomy

1 Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México

2 Tecnológico Nacional de México-Instituto Tecnológico de Aguascalientes, México

This study analyzes the entrepreneur reasons to create firms in a necessity/opportunity profile. The objective was to detail the effects of regulatory, normative and cognitive burdens on entrepreneurs’ behavior. The entrepreneur ecosystem combines economic and social conditions where entrepreneurs display their business activities. The study was transversal, probabilistic and explicative. The survey measured the institutional burdens and the entrepreneur profile (necessity vs opportunity). The sample tested was of 250 firms from Aguascalientes. The statistical method was linear regression. The results show that normative burdens are more significant to entrepreneurship figure when the firm was created by an opportunity business. The regulatory burden was highly variable in both sides (necessity vs opportunity profile). This social perspective causes institutional arrangements that has effects on environemental trust, business opportunities could be seized by entrepreneurial skills developed with institutional forces based on legal protection and certainty.

JEL code: L26; O17; J16

Keywords: Institutional aspects; Entrepreneur; By opportunity; Micro and small companies

El presente estudio analiza las razones por las que un emprendedor ha creado su empresa en dos perfiles principales: por necesidad o por oportunidad, con el objetivo de detallar como los emprendedores se ven influenciados por los aspectos regulativos, normativos y cognitivos, siendo estos conocidos como el ecosistema emprendedor que combina las condiciones económicas y sociales que forman el contexto donde los empresarios realizan sus actividades económicas. El estudio fue de corte transversal, probabilística y explicativa, se aplicó una encuesta para medir los aspectos institucionales y el perfil del emprendedor; fue aplicado en 250 micro y pequeñas empresas de la ciudad de Aguascalientes. Para testar los objetivos de la investigación se utilizó la técnica estadística de regresión lineal. Los resultados revelan que los aspectos normativos tienen efectos significativos para la figura emprendedora que ha iniciado su negocio a partir de la detección de una oportunidad en el mercado. Los aspectos regulativos fueron altamente variables en ambos perfiles. El problema fue analizado desde una perspectiva social lo que causa un bagaje institucional que influye en la confianza del entorno, proporcionando oportunidades de negocio que, si se cuentan con las habilidades emprendedoras necesarias, pueden ser aprovechadas por los emprendedores, ya que proporcionan protección y certidumbre.

Código JEL: L26; O17; J16

Palabras clave: Aspectos institucionales; Emprendedor; Por oportunidad; Micro y pequeñas empresas

Introduction

The entrepreneur is an important figure that guides change and leads to the economic growth of the region (Acs & Amorós, 2008). As the economic entities they are, entrepreneurs build ways to reduce the transaction costs to which they are subject to make efficient the constant processes of interaction they have with other actors who play a role within the institutional environment (D. Ali, 2015). When the existing friction of the institutional environment is strong, it is difficult to order and coordinate towards the same objective, causing uncertainty that causes entrepreneurs to act in an uncoordinated way in hostile conditions (Tang & Hull, 2012).

Economic entities create ways to reduce costs by repeating and executing them, generating a less uncertain environment because it orders and coordinates toward a common objective; these ways of ordering and coordinating are called institutions (North, 1990). Understanding institutions must be multidimensional and systematic, comprehending the entire institutional environment: Scott (1995) categorized the institutional environment into the regulatory, normative, and cognitive components. The regulatory aspect is the set of laws and rules in a national environment that promote or restrict the behavior of economic agents (Kostova, 1999). For its part, the normative aspect is the preexisting social structures that determine the confidence society places in the business sector (Kostova, 1999). Finally, the cognitive aspect represents the social knowledge shared in a general way associated with the business skills that identify the recognition and exploration of a business opportunity according to Stenholm, Acs, and Wuebker (2013). These aspects are important because they delineate how companies interact among themselves and stimulate local, regional, and national development (Ortega, Kamiya, & Fagre, 2013). Evaluating these three dimensions recognizes the business opportunities, challenges, and expectations which configure the positive or negative perception the population has of the business fabric that motivates or discourages entrepreneurship (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2014).

A variable with growing importance for the study of entrepreneurship is the motivation of individuals in society toward the create a company based on necessity or opportunity profiles. Given the conditions that precede entrepreneurship, it is logical to analyze the entrepreneurs who began their business intending to pursue an opportunity and who were not forced to choose to be entrepreneurs. Usually, entrepreneurs create a business because they want to make money or be more independent. On the other hand, ventures that exist for individual needs necessarily begin for different reasons such as involuntary loss of employment or lack of vacancies in the labor market; therefore, the decision taken involves a forced activity that becomes unsatisfactory (Angulo-Guerrero, Pérez-Moreno, & Abad-Guerrero, 2017).

The influence of institutions on the relative presence of ventures of opportunity is the most significant contribution of this study, given the important distinction between the characteristics of one entrepreneurial profile with respect to another. It generates the need for an exhaustive study of the phenomenon from empirical works that have compared the effects of institutional aspects on variables such as entrepreneurial orientation (Dwairi & Akour, 2014; Parga-Montoya, 2016; Ruiz-Ortega & Parra-Requena, 2014), which have identified the role that the rules of the game have on entrepreneurial behavior.

This study contributes to the analysis of institutional loads that promote the opportunity entrepreneur profile. The theoretical discussion focuses mainly on defining the institutions, as well as the proposal to address the entrepreneur profiles from the approach of the institutional loads of Kostova (1999) and Scott (1995). The methodology used was hypothesis testing through multiple linear regression. The results provided important findings on the behavior of the normative load, from which the implications of said results were subsequently issued, delving into the role of public policy makers in formulating institutions that encourage economic actors to identify business opportunities.

Review of the literature

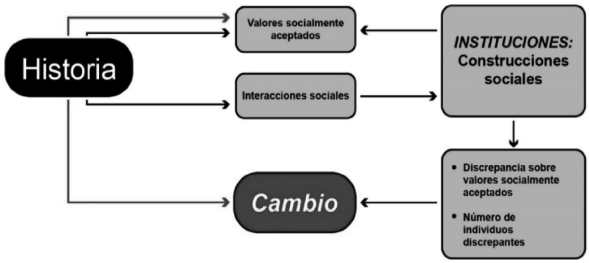

Understanding institutional theory starts from principles that summarize reality, simplifying the eventuality of the economic and social phenomena from the interrelations that obtain among the economic actors (North, 1990, 1994). It differs from other theories that address political and economic problems in the perspective, which combines the rational choice and highlights the symbolic systems of Behavioral Theory (Peters & Pierre, 1998), which is why it seeks to achieve social stability. From here, the word institution emerges, which functions as a designer of the behavior of the entities that interact between different economic, social, and even political changes of a region (Urbano, Vaillant, & Toledano, 2007). Institutions are a system of social constructs accepted within a particular place. Over time, the individuals of that society disagree with the conditions present in the system, and in order to refine the social interactions to make them more effective, they give rise to new interactions that modify the previous institutions (see Figure 1). The institution aims to reduce uncertainty by establishing a stable structure for economic and social interaction, modeling, in this case, entrepreneurial order.

Since Veblen (1899), social evolution has established that individuals are ruled by principles that gain relevance in their relationships with others and how their experiences gradually change to make them more frequent and economical. Coase (1937) bases the term on the behavior of organizations, allowing economic exchange, and stating that there is a system of relationships directed by the minimization of transaction costs. Simon (1958), on the other hand, argued that this economic position allowed the actors to receive and decode information given their limited rationality, where the need to create structures facilitates decision-making. By the 1970s, exponents of the new institutionalism such as DiMaggio and Powell (1983), Meyer and Rowan (1977), North (1990), Powell and DiMaggio (1991), Scott (1995), and Williamson (1975) converged on the same concept: to define individuals as the fundamental unit, making them producer and product of their circumstances (Hodgson, 2001).

The neo-institutional theory argues for the existence of institutions through transaction costs developed in order to avoid friction between economic exchanges, which are gradually learned by the entities as general rules that favor contracting (Williamson, 1975). Institutionally defined actors can delineate a business structure because the response of an organization in one environment corresponds to the responses of other organizations immersed in the same environment (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The present risks of the application of the law, the inherent protection of social norms, and the development of entrepreneurial cognitions involve a complex system established by institutional thinking with four primary characteristics contrary to its neoclassical predecessors: indeterminism, endogenous principle, behavioral realism, and diachronism (Scott, 1995).

By the same token, the way to evaluate the institutional environment has assumed different profiles, and studies have measured formal institutions (laws and regulations), considering those aspects that affect the economic and social aspects of the actors, such as governmental efficiency, economic policies, regulatory quality, and entrepreneurial support (Bjornskov, Dreher, & Fischer, 2010; Fogel, 2001; Peng, 2003; Roxas & Chadee, 2013). Other studies have analyzed institutions not only as formal components, but also as informal aspects that culturally and socially affect business behavior (Gupta et al., 2012; Levie & Autio, 2011; Misangyi, Weaver, & Elms, 2008; Tonoyan, Strohmeyer, Habib, & Perlitz, 2010).

The growing number of studies with this perspective in the business sector, particularly in entrepreneurship, has become relevant due to the importance of creating an environment conducive to new entrepreneurs (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Chowdhury, Terjesen, & Audretsch, 2015; Danis, De Clercq, & Petricevic, 2011; De Clercq, Danis, & Dakhli, 2010; De Clercq, Meuleman, & Wright, 2012). One of the agencies most dedicated to studying the institutional aspects that affect entrepreneurship is the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (2014b), which has devoted outstanding efforts to measuring the economic environment in which entrepreneurs interact in order to visualize and unravel the reality that influences their behavior. The annual study carried out by this agency worldwide aims to reveal information relevant to the institutional context affecting entrepreneurs. This agency provides evidence on the regulatory, normative, and cognitive loads at a global level. Similarly, in Mexico (although not as outstandingly and without specifying which ones), six federal institutions have been considered to study the institutions.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem is comprised in the first instance of the regulatory aspect, which analyzes the commercial and legal infrastructure to which all entrepreneurs have access, that is, to the impartial protection obtained from carrying out an economic activity in a country or region. Table 1 illustrates that the countries that belong to the efficiency-based category, which includes Mexico, have lower values than those obtained from the innovation-based countries. The score of 4.7 out of 9 indicates that these countries lack sufficient factors to take care of the state of law of each of the entrepreneurs.

Table 1 Regulatory, normative, and cognitive aspects

| Country | Reg | Nor | Cog | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency-based economies | Mexico | 4.7 | 5.0 | 2.6 |

| China | 4.3 | 5.0 | 2.6 | |

| Innovation-based economies | Canada | 6.3 | 5.9 | 4.1 |

| USA | 5.4 | 6.8 | 3.5 | |

| United Kingdom | 5.0 | 5.3 | 4.0 | |

| Norway | 5.5 | 4.7 | 4.1 | |

Source: own elaboration based on the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2014)

The following three indicators evaluate the normative aspect: societal perception of a career as an entrepreneur, whether society believes that the entrepreneur has a high status, and the attention the media gives to entrepreneurs. Together, the three perceptions determine the attractiveness and visibility of the entrepreneurial activity; the better the social perception, the greater the possibility for entrepreneurs to acquire investors, suppliers, and advisors. The results of the study display the social perception of the countries and illustrate that the normative aspect of Mexico has been more restrictive than that of countries such as China, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Norway. The implication is that in the environment, there is confidence in the companies on the part of investors, suppliers, and advisors of the economies, thus leading to the conclusion that these economies focus on increasing the efficiency of their economic sectors (see Table 1).

The following four indicators measure the cognitive aspect of the GEM methodology: 1) perceived good opportunities to start a business within the next six months, 2) having the necessary abilities to start a business, 3) having a positive attitude toward failure, and 4) having plans to start a business within the next three years. In the case of Mexico, personal abilities and perceptions are held back by the fear of failure regardless of how qualified an entrepreneur is to identify opportunities and their capabilities (see Table 1).

The study by Minniti (2012) concludes that the difference between these two classifications lies in the growth a company can achieve. The conditions before the start of operations of a micro or small enterprise make it possible to discern whether the decisions to start a new business were taken from a position of detecting opportunities, which means that whoever decides for the business can risk capital for new businesses, thus encouraging a constant behavior of innovation and competition.

According to Williams and Williams (2014), the primary role of entrepreneurs motivated by business opportunities sharpens their characteristics when they look to exploit an opportunity, preceded by an environment developed to high levels of entrepreneurial behavior where entrepreneurship is less limited. They argue that the understanding of business creation by the public policy is the first step to progress toward the presence of motivations shared in the socio-spatial context.

Van Stel, Carree, and Thurik (2005) discuss how the minimum capital required to start is the greatest barrier of entry for entrepreneurs, limiting even the most capable in their ability to seize opportunities, innovate, or compete strategically. The results of the exploratory study of entrepreneurial activity illustrate that companies are willing to take advantage of opportunities, innovate, or act proactively. 71.4% marketed new products within the last five years, 66.3% believe that they are in a challenging position with regards to the competition, and 64.3% stated that they choose an aggressive posture to maximize the results of taking advantage of opportunities.

Similarly, Van Stel, Storey, and Thurik (2007) indicate in their study that in countries with burdensome regulations, entrepreneurs are reluctant to register their businesses and are willing to operate informally. A more disturbing finding is that the “most regulated” countries are also the poorest. According to the study, in Mexico, it takes an average of 58 days for a company to open a business, which places it among the five worse countries in terms of business procedures. The Netherlands, France, Canada, Germany, and the United States reflect a nascent entrepreneurship favored by regulations and legal controls. In these countries, there is a high business opportunity index; thus, entrepreneurs based in these countries start up because they detect a business opportunity and not out of necessity, which reduces their field of action to make decisions conscientiously.

Therefore, institutions restrict the positive characteristics of companies, similarly to what Tang and Hull (2012) concluded about the influence of a hostile environment, which causes a more challenging and daring entrepreneurial orientation out of the need to survive and not because of the detection of opportunities that will enable the growth of small and micro enterprises, although when it is excessive, it will likely cause a high rate of decrease in the place. The exploratory study supports the results that suggest relationships of regulatory load and entrepreneurial capacity because, as previously mentioned, in a hostile, restricted, and discriminatory environment companies adopt an aggressive and competitive position but with a lack of innovation knowledge.

The activity of individuals to determine business opportunities, develop ideas that materialize into innovative products, and direct their efforts to compete, is a variable that elicits great interest for many researchers (Boso, Story, & Cadogan, 2013; Slevin & Terjesen, 2011; Smart & Conant, 2011). It should be noted that companies that manage to orient themselves towards entrepreneurship stimulate in a certain way the growth of an economy based on innovation (Ferreira, Garrido, & Fernández, 2011; Hansen, Deitz, Tokman, Marino, & Weaver, 2011; Roxas & Chadee, 2013). When this occurs it is legitimate to ask whether companies analyze the environment or the environment itself plays an important role in triggering this orientation (Ruiz-Ortega & Parra-Requena, 2014).

In an economy, economic actors such as people, families, companies, and government interact, and pre-created conditions of knowledge acquired over time guide the individual decisions of these agents (Levie & Autio, 2011). Institutions coordinate the structure and order of society, thus the recognition they have in the business field is modeled through the institutional facets (Gupta et al., 2012). Structure and behavior differ in each individual, and what must be considered is the role of institutions in homogenizing (i.e., without affecting their variation) the recognized constitution of the economic actors. Elements of the external environment such as available technology, dynamism, hostility, and the stage of the industry are crucial aspects in entrepreneurial activity, particularly for micro and small enterprises since they are more susceptible to sudden changes when there is economic and social turbulence in a region (Covin & Slevin, 1989, 1991; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Mintzberg, 1973). Institutional analysis is one way to reconfigure an approach that addresses the complexity of the environment to respond to the knowledge of why and where entrepreneurial activity occurs, mainly to generate structurally dissimilar context comparisons (Miller & Breton-Miller, 2011).

The institutional framework gives the intentions of the people who start a business. For this reason, the priorities of government policies have been directed in recent years to local development through the promotion of competitive business abilities. The aim is to stimulate entrepreneurship and innovation, as well as generate a flexible institutional structure for the different productive sectors, which would allow the territory to achieve a competitive advantage that provides a collection of resources for any entrepreneurial activity (Díaz-Casero, Ferreira, Hernández Mogollón, & Barata Raposo, 2012). Its main function as an economic entity is to investigate the economic conditions of a region to determine a rational behavior to choose the “best option for its benefit” (M. Peng, Sun, Pinkham, & Chen, 2009). In this sense, when in a decision-making cycle, what others have done serves as a guide for those who are about to make similar decisions. In this loop of social constructs the individual becomes the product and producer of their circumstances (Hodgson, 2001).

As previously stated, the usefulness of analyzing the factors that affect the entrepreneur in an unstable economy is that it makes it possible to determine which aspects of the institutional structure affect to a greater extent the interactions and processes of a better entrepreneurial activity, given that these condition its scope, achieving a greater dynamic capacity of decision-making oriented towards entrepreneurship (García-Cabrera, García-Soto, & Días-Furtado, 2015). The promotion of entrepreneurial activity must be based on an environment that protects, conserves, and provides the necessary resources to take advantage of opportunities that the entrepreneurs themselves are willing to risk in order to achieve them. It must, therefore, be taken into consideration that sometimes individuals in emerging economies lack the choice to pursue a business opportunity because when they are willing to create a new company, they do so for different reasons such as having lost their job or lack of economic capacity (García-Cabrera et al., 2015). In developed countries, it is common that those who risk carrying out a business idea have identified the market, developed the necessary technical study, and concluded that the company they would create is a viable opportunity to exploit (Hechavarria & Reynolds, 2009).

Gupta et al. (2012) carried out a study on the institutional environments of Brazil, China, India, and South Korea, and the entrepreneurial capability they have to identify, evaluate, and exploit new opportunities in companies. The results reveal that Brazil was the country with the lowest indices of entrepreneurship due to the cognitive aspect. On the other hand, India had the highest indices, benefiting from the investment in education; however, the regulatory aspect is low and affects the performance of its entrepreneurs. It is also evident that the regulatory aspect has a tendency in these countries to “de-bureaucratize,” so it is increasingly easier to start a new business and develop entrepreneurial capabilities, although cultural differences impact on the social perception of these.

Tang & Hull (2012) compared the differences between Chinese companies and those from western economies, particularly the influence a competitive and hostile environment has on the entrepreneurs. The comparison highlights how entrepreneurs in the west adopt a posture of constant innovation to survive competition, whereas Chinese entrepreneurs do not take advantage of opportunities because of the lack of protection of rights and intellectual property, causing unfair competition and generating higher costs for the government in trying to control it. Therefore, they deduce that while new entrepreneurs have the innovation and risk-taking strategies, those in charge of the institutions need to strengthen them.

Method

The entrepreneurial ecosystem has great influence as illustrated by previous empirical studies; thus, this study aimed to analyze the influence of institutional aspects on the entrepreneurial profile, considering those who have created their company by detecting a business opportunity compared to those who did so out of necessity. Based on the above, the following hypotheses are established:

H1: There is a significant influence of the regulatory aspect on the entrepreneurial profile.

H2: There is a significant influence of the normative aspect on the entrepreneurial profile.

H3: There is a significant influence of the cognitive aspect on the entrepreneurial profile.

Since the main purpose is to determine the impact of the institutional aspects on the entrepreneurial profile of small and micro enterprises in the city of Aguascalientes, the hypotheses were statistically tested in order to establish the degree of influence a variable has with respect to others. This cross-sectional study establishes a causal relationship of an independent variable with the dependent variable, which Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black (2014) define as an explicative study.

The set of companies chosen for the empirical study were small and micro enterprises of the city of Aguascalientes, which in recent years has obtained the top places in ease of doing business according to the study Doing Business (World Bank, 2018). The choice of two types of enterprise is because the characteristics of micro-enterprises are not separate from small enterprises; therefore, their analysis must be as a whole and separate from medium and large enterprises (Berrone, Gertel, Giuliodori, Bernard, & Meiners, 2014). The role of small and micro enterprises represents an opportunity for the economy as a potential source of flexible and adaptable resources and capabilities during times of crisis, as well as employment generators when the country needs it because of the ease with which they are set up (A. Ali, 2012; Ayyagari, Thorsten, & Asli, 2003; Camisón-Zornoza & Lucio, 2010). The weak consolidation that small companies have in countries such as Mexico causes fragile and stagnant economic growth based on volatile and, consequently, informal companies (Hsieh & Klenow, 2012; Sanguinetti, 2013).

The classification considered for this study is the one established by the Secretariat of Economy (2010). The companies considered in the study are those within a range of 1 to 30 employees, in order to include the small and micro enterprises of the three main areas: commerce, industry, and services. The set of companies came from the database of the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units, which is a regularly updated source of INEGI, originating from the 2009 Economic Census with information from more than 4,000,000 companies established in Mexico based on their economic activities, size, and geographic area (2013). From this database, the target population is the economic units with fewer than 30 employees within the Basic Geostatistics Areas (BGEAs) found in the urban area of the city of Aguascalientes. When searched, it provided a total of 40,529 micro and small enterprises.

The sample size is calculated to give estimates to the previous observation units; concerning this, the sample sizes are estimated based on the following expression (Aguilar-Barojas, 2005). The expected proportion to be achieved is 50% of the population since there is no previous history of the variables in question in the city of Aguascalientes, with a significance level of 5% and an accuracy level of 7.5%, obtaining the following:

For the design of the sampling scheme, INEGI was consulted for support in formulating a probabilistic, two-stage, cluster sampling, which has the following characteristics:

Probabilistic, due to the selection units having a known, non-zero probability of entering the sample; therefore, the exact sampling results are known.

By geographical clusters.

Before the sample survey, a pilot test was carried out with businesspeople affiliated to the state government program called Pride of Aguascalientes, which proved the reliability and statistical validity of the indicators and the data collection process continued.

The sample survey was two-stage since the selection of the unit of analysis was chosen in two stages:

First stage of sampling: within the city of Aguascalientes, of the 272 BGE-As that comprise the urban area, with these already identified a simple random sample of 71 BGEAs was calculated, and randomly selected in order to disseminate the data collection work in specified areas and not traverse the entire geographical area of the city

Second stage of sampling: with the chosen BGEAs, the selection of the 300 economic units specified in the sample determination was arranged to establish the known, non-zero probability without preference to be chosen

The information survey was based on the route of the BGEAs selected for information gathering, with the instruction to visit the economic units no more than five times in order to complete the survey within two months. Only 250 cases were obtained under this condition because of business entity closure. The surveyed companies were given priority for it to be in situ in order to answer the measurement instrument correctly; however, when the appropriate informant was not available, a questionnaire was left.

For institutional loads the instrument of Kostova & Roth (2002) was adapted on a five-point Likert scale divided into the three dimensions classified by Scott (1995): regulatory, with six indicators that correspond to the perception that companies have of laws, regulations, and bureaucratic procedures; the normative load, with five indicators that measure the appreciation of companies of the social and general thinking of entrepreneurs in the country; finally, the cognitive aspect has five indicators that evaluate the perception that companies have of the skills entrepreneurs have in the country. For the entrepreneurial profile, the indicator used evaluates the entrepreneur on their reason for entrepreneurship: either identifying an opportunity or having the necessity to create their business.

In order to test the objectives of the study, it was necessary to use the linear regression statistical technique to explain the effects of the regulatory, normative, and cognitive aspects on the two entrepreneurial profiles. For this purpose, a statistical reliability and validity analysis was carried out for the measurement scales, as well as a confirmatory factorial analysis. The Cronbach alpha (Cronbach, 1951) provided values above 0.7 (Nunnally, 2009). Similarly, the calculation of the IFC yielded results above what was considered by Hair et al. (2014), and with regard to the AVE, it provided indices above 0.5 (Cuevas-Vargas, 2016; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2014). The above tests the communality of each manifested variable, explaining that the indicators are correlated with the latent variable, which ensures that the variables converge successfully (Byrne, 2008; Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Mena, 2012) (see Table 2).

Table 2 Reliability and validity analysis of the measurement instrument

|

|

Indicators | Convergent validity | Reliability of the internal consistency | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.631 | 0.895 | 0.854 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.643 | 0.878 | 0.813 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.721 | 0.886 | 0.806 |

Source: own elaboration with the results obtained with Smart PLS 3 (Ringle et al., 2015)

The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT90) (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015) was measured in order to estimate the discriminant validity of the model, which requires the Bootstrapping procedure to obtain the variability of the estimated parameters. The results illustrate the correlations of the reflective constructs below 0.9, which signify an adequate discriminant validity (Gold & Arvind Malhotra, 2001; Henseler et al., 2015; Teo, Srivastava, & Jiang, 2008) . Similarly, the Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion was calculated, concluding that the value is above the correlation. The cross-loadings analysis illustrates the discrimination of the indicators since they are associated with the highest factorial load of the corresponding construct (Chin, 1998)(see Table 3).

Table 3 Discriminant validity of the measurement instrument

| Lower order constructs |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: The numbers in diagonal (bold) represent the square of the AVE values. The values above the diagonal are those of the HTMT.90 test and those below the diagonal are those of the Fornell-Larker criterion test.

Source: own elaboration with results obtained with Smart PLS 3. (Ringle et al., 2015)

In conclusion, based on this analysis, the measurement instruments were reliable and valid for further testing of the hypothesis.

Results

For an overview of the variables analyzed, starting with the regulatory aspect, it is of note that the variability of this factor is greater than one point on the Likert scale, which means that there is a discordance between the regulatory aspect on the part of the companies, that is, in some cases, they can agree, and in others disagree (see Table 4). These results are similar to those D. Ali (2015) obtained for the regulatory aspect, placing it at an average value of 2.6 on a five-point Likert scale but with a standard deviation of 0.4, which is lower than that reported in this analysis.

Table 4 Descriptive statistics of the regulatory aspect

| Institutional aspects | Mean | Standard Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory |

|

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on the statistical software IBM SPSS v. 23

Similarly, the international study by Dwairi and Akour (2014) illustrated results below the Likert point, the lowest of the three aspects, representing a restrictive environment for small and micro-enterprises.

Therefore, the results given in the analysis show a high degree of variability in the regulatory aspect, which indicates a very different environment for each of the respondents. In their study, Eunni and Manolova (2012) stated that their results in Russia had standard deviations above the Likert point, concluding that this is an indication that laws and regulations are applied irregularly because it means some respondents stated that they were being legislated differently depending on their relationship with government officials.

The results concerning the normative aspect measured the confidence in the environment for small and micro enterprises. Those questioned believed that for the majority of entrepreneurs starting a company is a good option to become rich, they are considered to have a good reputation, and are thought to be competent and resourceful. Similarly, it is considered that the mass media transmit this vision through stories of successful entrepreneurs. These results reflect that the environment has social norms that recognize and accept the activities of entrepreneurs. Society assimilates the entrepreneurial activities and catalyzes them as a valued proposal process for the formation of innovative thinking. A comparison of the values close to four points of the normative aspect (see Table 5) with those obtained by Dickson and Weaver (2008), in which the normative elements are of 4 points, suggests a social agreement for the development of business activities.

Table 5 Descriptive statistics of the normative aspect

| Institutional aspects | Mean | Standard Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normative |

|

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on the statistical software IBM SPSS v. 23

The cognitive aspect represents social knowledge and skills in the environment that empowers companies. The five indicators obtained the lowest means of the institutional aspects (see Table 6); specifically, the experience and ease of undertaking a business venture obtained means positioned in the central point, which implies that the stimulation of symbolic exposures do not motivates the individual business activities. Similarly, variability is close to the Likert point, causing the variability to tilt the data distribution toward disagreement.

Table 6 Descriptive statistics of the cognitive aspect

| Institutional aspects | Mean | Estandar Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive |

|

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on the statistical software IBM SPSS v. 23

Concerning the hypotheses established, the results of the variables considered in the regression model present a correlation coefficient of 0.250, and a determination coefficient of 0.062, which, according to Cohen (1988), is an R2 statistically significant to the sample size considered (see Table 7).

Table 7 Model summary

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .250a | .062 | .051 |

a. Predictors: (Constant), AC, AN, AR

b. Dependent variable: REASON

Source: own elaboration based on the statistical software IBM SPSS v23

Fisher’s F obtained a value of 5.463 with a significance of 0.001, which indicates that the proposed model has an adjustment with coefficient typified in the normative aspect variable of 0.203, significant at 5%, while the regulatory and cognitive aspects do not have significance for the regression model (see Table 8). In order to conduct the regression model, it was necessary to generate three new indicators based on the means of the manifested variables that comprise each dimension. The generation of new variables corresponds to that expressed by Hair et al. (2014) to analyze variables manifested as a whole in new first-order variables.

Conclusions

From the statistical point of view, the normative dimension, which corresponds to social perception, illustrates how the environment provides confidence to entrepreneurs to be able to interrelate in order to develop their business skills. It is this dimension that significantly influences the behavior of the sector. The results of Hechavarria and Reynolds (2009) share similar values, which suggests that motivations correspond to contextual understanding, given that certain cultural values can lead to the formation of successful new companies, and greater economic dynamism. According to the goals pursued by new entrepreneurs, the formation of the company can be more easily predicted from the three entrepreneurial perceptions that comprise the normative aspect: 1) perception of desirable personality, 2) perception of social support, and 3) perception of feasibility.

The origin of the opportunities that entrepreneurs have is not merely individual but based on the previous institutional baggage that guides their skills, confidence in the environment, and the protection they can obtain from this environment. Concerning the latter, the results outline what several researchers have stated, that the normative aspect that is present in Latin American countries responds to the fact that the environment has confidence (Aparicio, Urbano, & Audretsch, 2016; Fuentelsaz, González, Maícas, & Montero, 2015; Volchek, Saarenketo, & Jantunen, 2015); however, many of the regulatory factors such as laws, rules, and formal norms are not applied fairly and impartially. On the contrary, they tend to favor certain stake-holders that converge in the institutional environment, as illustrated by the high variability of the indicators of the regulatory aspect, since for some entrepreneurs, the regulatory aspect is not as benevolent as for others.

As detailed when the problem was first stated, economic actors in the economic environment interact and make individual decisions guided by institutional aspects that reduce the interaction costs and the negative effects of the decisions made (North, 1990; Scott, 1995, 2008). For this reason, it was essential to demonstrate the importance of the institutional environment, so it is appropriate to emphasize that the international bodies (World Bank, 2015; Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2014; Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, 2014) consulted for the study of the institutional environment did not provide empirical information to measure the effects of the regulatory, normative, and cognitive aspects on the identification of business opportunities. In conclusion, the rules of the game are important for the development of a better entrepreneurial environment.

The study focused on adding a grain of knowledge to the empirical study of the institutional aspects as a viable solution of endogenous character to current situations at the local, regional, and national levels. It primarily makes it possible to analyze the problem from a perspective that involves society as a whole, with the central axis being the creation of companies with high added value. External factors require a greater understanding of the institutional forces that influence the skills of those who manage companies, since the aggressive posture of the entrepreneurs is due in great measure to the lack of opportunities in an adequate state of legal protection, a better system of social values that generate confidence in entrepreneurs, and a complex blueprint that allows the social transmission of knowledge and management skills necessary to start a new business. Entrepreneurial practices are the accumulation of disseminated efforts that directly affect the decisions taken. The environment, sometimes unfavorable, is weakened by the lack of the rule of law combined with the fragility of the interpretation of the eventualities of supply and demand.

It is decisive that the three loads converge in promoting entrepreneurial activities that encourage business opportunities. The normative and cognitive aspects evolve gradually since they represent the adaptation of social structures that mutate based on understanding the differences between historical states before states of social change. Therefore, according to the results obtained, in order to benefit the entrepreneurial environment, it is necessary to develop public policies that provide greater interest to the confidence of entrepreneurial behavior, where interests are compatible within the social spectrum. This spectrum is characterized by an encouraging landscape for social values, such as the satisfaction of being an entrepreneur, acceptance of a good reputation as an entrepreneur, and competition in entrepreneurial activities, which are cultivated through the generation of certainty in social interactions.

From a particular approach, the authors conclude that when the institutional environment is hostile, opportunities are scarce, which generates a tendency to adopt an aggressive posture, without conscientious decision-making (Ntayi, Mutebi, Kamanyi, & Byangwa, 2013; Tang & Hull, 2012; Zahra & Garvis, 1996). That is to say that the management processes developed by entrepreneurs for decision-making are full of misconceptions about how to evaluate the market since they lack the necessary skills, reinforced by an adequate legal framework, and a value system that strengthens entrepreneurial capabilities.

Since the normative load behaves differently, it is necessary to consider further studies that relate the institutional configuration to the elements that determine a social approach based on the recognition of individuals in charge of performing economic activities, by virtue of social values that cover the widespread perception of business owners on issues considered from age, gender, and even social class.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments to the National Council on Science and Technology for providing the necessary funding to train the authors and prepare this project. Likewise, acknowledgments to the entrepreneurs who participated in the information-gathering period.

REFERENCES

Acs, Z. J., & Amorós, J. E. (2008). Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 305-322. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9133-y [ Links ]

Aguilar-Barojas, S. (2005). Fórmulas para el cálculo de la muestra en investigaciones de salud. Salud en Tabasco, 11(1-2), 333-338. [ Links ]

Ali, A. (2012). On the Structure and Internal Mechanisms of Business Incubators: A Comparative Case Study. Irlanda: DCU Business School, Dublin City University. [ Links ]

Ali, D. (2015). The effects of demographic, cognitive and institutional factors on development of entrepreneurial intention: Toward a socio-cognitive model of entrepreneurial career. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 13, 452-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-015-0144-x [ Links ]

Angulo-Guerrero, M., Pérez-Moreno, S., & Abad-Guerrero, I. (2017). How economic freedom affects opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in the OECD countries. Journal of Business Research (73), 30-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.017 [ Links ]

Aparicio, S., Urbano, D., & Audretsch, D. (2016). Institutional factors opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technological Forecasting & Social Change (102), 45-61. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.04.006 [ Links ]

Ayyagari, M., Thorsten, B., & Asli, D.-K. (2003). e-Library: Small and Medium Enterprises across the Globe: A New Database. sitio web de The World Bank. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/content/workingpaper/10.1596/1813-9450-3127 [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2015). Ranking del estudio Doing Business 2015. Retrieved from http://espanol.doingbusiness. org/rankings [ Links ]

Berrone, P., Gertel, H., Giuliodori, R., Bernard, L., & Meiners, E. (2014). Determinants of Performance in Microenterprises: Preliminary Evidence from Argentina. Journal of Small Business Management, 477-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12045 [ Links ]

Bjornskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: Revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 419-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ejpoleco.2010.03.001 [ Links ]

Boso, N., Story, V., & Cadogan, J. (2013). Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, network ties, and performance: Study of entrepreneurial firms in a developing economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 708-727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.04.001 [ Links ]

Bowen, H., & De Clercq, D. (2008). Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 747-767. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25483297 Consultado: 21/10/2015 [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2008). Structural equation modeling with EQS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. New Jersey, USA: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Camisón-Zornoza, C., & Lucio, J. J. (2010). La competitividad de las PYMES españolas ante el reto de la globalización. Economía industrial, 375, 19-40. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3197368 Consultado: 12/05/2015 [ Links ]

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (Vol. 295, pp. 295-336). New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Chowdhury, F., Terjesen, S., & Audretsch, D. (2015). Varieties of entrepreneurship: institutional drivers across entrepreneurial activity and country. European Journal of Law and Economics, 40(1), 121 bv148. doi:10.1007/ s10657-014-9464-x [ Links ]

Coase, R. (1937). The Nature of the Firm. Economica, 4(16), 386-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Hillsdale, NJ, 20-26. [ Links ]

Covin, J., & Slevin, D. (1989). Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 75-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107 [ Links ]

Covin, J., & Slevin, D. (1991). A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879101600102 [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555 [ Links ]

Cuevas-Vargas, H. (2016). La influencia de la innovación y la tecnología en la competitividad de las Pymes manufactureras del estado de Aguascalientes. (Ph.D.), Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Mexico. [ Links ]

Danis, W., De Clercq, D., & Petricevic, O. (2011). Are social networks more important for new business activity in emerging than developed economies? An empirical extension. International Business Review, 20, 394-408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.08.005 [ Links ]

De Clercq, D., Danis, W., & Dakhli, M. (2010). The moderating effect of institutional context on the relationship between associational activity and new business activity in emerging economies. International Business Review, 19, 85-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.09.002 [ Links ]

De Clercq, D., Meuleman, M., & Wright, M. (2012). A cross-country investigation of micro-angel investment activity: The roles of new business opportunities and institutions. International Business Review, 21, 117-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.02.001 [ Links ]

DOF, Diario Oficial de la Federación 29/12/2010, (2010). Disponible: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5173063&fecha=29/12/2010 [ Links ]

Díaz-Casero, J. C., Ferreira, J. J. M., Hernández Mogollón, R., & Barata Raposo, M. L. (2012). Influence of institutional environment on entrepreneurial intention: a comparative study of two countries university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(1), 55-74. doi:10.1007/s11365-009-0134-3 [ Links ]

Dickson, P., & Weaver, M. (2008). The role of the institutional environment in determining firm orientations towards entrepreneurial behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal (4), 467-483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0088-x [ Links ]

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160. doi: 10.2307/2095101 [ Links ]

Dwairi, M., & Akour, I. (2014). The moderating role of country institutional profile on the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationships in the service industry. International Journal of Business, Marketing, & Decision Science, 7(1), 80-94. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.dibpxy.uaa.mx/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=644b1710-2b44-4a36-980b-d55e46e0801f%40pdc-v-sessmgr03 Consultado: 11/08/2016 [ Links ]

Eunni, R., & Manolova, T. (2012). Are the BRIC economies entrepreneur-friendly? An Institutional Perspective. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 20(2), 171-202. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495812500082 Consultado: 03/11/2014 [ Links ]

Ferreira, J., Garrido, S., & Fernández, R. (2011). Contribution of Resource-Based View and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Small Firm Growth. Cuadernos de Gestión, 11(1), 95-116. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=274319549005 [ Links ]

Fogel, G. (2001). An Analysis of Entrepreneurial Environment and Enterprise Development in Hungary. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 103-109. https://doi.org/10.1111/0447-2778.00010 Consultado: 21/10/2015 [ Links ]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104 [ Links ]

Fuentelsaz, L., González, C., Maícas, J., & Montero, J. (2015). How different formal institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. Business Research Quarterly (18), 246-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. brq.2015.02.001 [ Links ]

García-Cabrera, A. M., García-Soto, M. G., & Días-Furtado, J. (2015). Emprender en Economías Emergentes: el Entorno Institucional y su Desarrollo. Innovar, 25, 133-156. https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v25n57.50357 [ Links ]

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2014). Monitor Global de la Actividad Emprendedora. México 2013. Sitio web de GEM. http://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/3368/gem-mexico-2013-report [ Links ]

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Producer). (2014b). What is GEM? Sitio web de la Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. Retrieved from http://www.gemconsortium.org/What-is-GEM [ Links ]

Gold, A. H., & Arvind Malhotra, A. H. S. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214. [ Links ]

Gupta, V., Guo, C., Canever, M., Yim, H., Sraw, G., & Liu, M. (2012). Institutional environment for entrepreneurship in rapidly emerging major economies: the case of Brazil, China, India, and Korea. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0221-8 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6 [ Links ]

Hansen, J., Deitz, G., Tokman, M., Marino, L., & Weaver, M. (2011). Cross-national invariance of the entrepreneurial orientation scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 61-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.05.003 [ Links ]

Hechavarria, D. M., & Reynolds, P. D. (2009). Cultural norms & business start-ups: the impact of national values on opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(4), 417. doi:10.1007/s11365-009-0115-6 [ Links ]

Henisz, W., & Levitt, R. (2011). Regulative, Normative and Cognitive Institutional Supports for Relational Contracting in Infrastructure Projects. Collaboratory for Research on Global Projects. https://gpc.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/wp055-1_0.pdf [ Links ]

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 [ Links ]

Hodgson, G. (2001). El enfoque de la economía institucional. Análisis Económico, 16(33), 3-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2001.181.48468 [ Links ]

Hsieh, C., & Klenow, P. (2012). The Life Cycle of Plants in India and Mexico. NBER Working Paper Series. http://www.nber.org/papers/w18133 [ Links ]

INEGI. (2013). Banco de Información INEGI. Retrieved from http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/biinegi/?ind=3103003004#A [ Links ]

Instituto Mexicano de la Competitividad. (2014). Índice de Competitividad Internacional 2014. Sitio web de IMCO. http://imco.org.mx/competitividad/indice-global-de-competitividad-2014-2015-via-wef/ [ Links ]

Kostova, T. (1999). Transnational Transfer of Strategic Organizational Practices: A Contextual Perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 308-324. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.1893938 [ Links ]

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2002). Adoption of an Organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects. Academy of Management, 45(1), 215-233. doi: 10.2307/3069293 [ Links ]

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2011). Regulatory Burden, Rule of Law, and Entry of Strategic Entrepreneurs: An International Panel Study. Journal of Management Studies, 1392-1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01006.x [ Links ]

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. (1996). Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking it to Performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568 [ Links ]

Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340-363. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2778293 Consultado: 18/09/2015 [ Links ]

Miller, D., & Breton-Miller, I. (2011). Governance, Social Identity, and Entrepreneurial Orientation in Closely Held Public Companies. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 35(5), 1051-1076. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00447.x [ Links ]

Minniti, M. (2012). El emprendimiento y el crecimiento económico de las naciones. Economía Industrial (383), 23-30. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3903869 [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. (1973). Strategy-Making in Three Modes. California Management Review, 16(2), 44-53. https://doi.org/10.2307/41164491 [ Links ]

Misangyi, V., Weaver, G., & Elms, H. (2008). Ending Corruption: The Interplay Among Institutional Logics, Resources, and Institutional Entrepreneurs. Academy of Management, 33(3), 750-770. doi: 10.2307/20159434 [ Links ]

North, D. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

North, D. (1994). Economic Performance Through Time. The American Economic Review, 84(3), 359-368. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118057 Consultado: 08/10/2014 [ Links ]

Ntayi, J. M., Mutebi, H., Kamanyi, S., & Byangwa, K. (2013). Institutional framing for entrepreneurship in sub‐ Saharan Africa: a case of Uganda. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 9(2/3), 133-154. doi:doi:10.1108/WJEMSD-01-2013-0016 [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. (2009). Teoría Psicométrica. México: Trillas. [ Links ]

Ortega, D., Kamiya, M., & Fagre, E., Stern, Mauricio. (2013). Políticas para el emprendimiento, el empleo y la productividad. In Emprendimientos en América Latina: Desde la subsistencia hacia la transformación productiva (pp. 203-269). Colombia: Corporación Andina de Fomento. [ Links ]

Parga-Montoya, N. (2016). La influencia de los aspectos institucionales en la orientación emprendedora y las redes de trabajo de las pequeñas y micro empresas de la ciudad de Aguascalientes. (PhD), Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, Mexico. [ Links ]

Peng, M., Sun, S., Pinkham, B., & Chen, H. (2009). The Institution-Based View as a Third Leg for a Strategy Tripod. Academy of Management, 23(3), 63-81. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2009.43479264 [ Links ]

Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional Transitions and Strategic Choices. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275-296. doi:10.2307/30040713 [ Links ]

Peters, G., & Pierre, J. (1998). Institutions and Time: Problems of Conceptualization and Explanation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(4), 565-583. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart. a024396 [ Links ]

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Roxas, B., & Chadee, D. (2013). Effects of formal institutions on the performance of the tourism sector in the Philippines: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Tourism Management, 37, 1-12. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.016 [ Links ]

Ruiz-Ortega, M. J., & Parra-Requena, J. R. (2014). Environmental dynamism and entrepreneurial orientation. The moderating role of firm’s capabilities. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26(3), 475-493. [ Links ]

Sanguinetti, P. (2013). Emprendimientos en América Latina: Desde la subsistencia hacia la transformación productiva. Colombia: Corporación Andina de Fomento. [ Links ]

Santizo, C. (2007). El Neoinstitucionalismo y las interacciones sociales. Ide@s CONCYTEG, 2(28), 742-751. [ Links ]

Scott, R. (1995). Institutions and Organizations. EUA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Scott, R. (2008). Approaching adulthood: the maturing of institutional theory. Theory adn Society, 37(5), 427-442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-008-9067-z [ Links ]

Simon, H. (1958). Models of Man. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53(282), 600-603. [ Links ]

Slevin, D., & Terjesen, S. (2011). Entrepreneurial Orientation: Reviewing Three Papers and Implications for Further Theoretical and Methodological Development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 973-987. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00483.x [ Links ]

Smart, D., & Conant, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial Orientation, Distinctive Marketing Competences and Organizational Performance. Journal of Applied Business Research, 10(3), 28-38. doi: 10.19030/jabr.v10i3.5921 [ Links ]

Stenholm, P., Acs, Z., & Wuebker, R. (2013). Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 176-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusvent.2011.11.002 [ Links ]

Tang, Z., & Hull, C. (2012). An Investigation of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Perceived Environmental Hostility, and Strategy Application among Chinese SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 132-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00347.x [ Links ]

Teo, T. S., Srivastava, S. C., & Jiang, L. (2008). Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(3), 99-132. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222250303 [ Links ]

Tonoyan, V., Strohmeyer, R., Habib, M., & Perlitz, M. (2010). Corruption and Entrepreneurship: How Formal and Informal Institutions Shape Small Firm Behavior in Transition and Mature Market Economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 803-832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00394.x [ Links ]

Urbano, D., Vaillant, Y., & Toledano, N. (2007). Nuevas empresas e instituciones de apoyo: el caso de la promoción empresarial en los ámbitos rurales y urbanos de Cataluña. Revista Española de Estudios Agrosociales (214), 103-126. [ Links ]

Van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2005). The Effect of Entrepreneurial Activity on National Economic Growth. Small Business Economics, 24, 311-321. Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40229425 Consultado: 21/10/2015 [ Links ]

Van Stel, A., Storey, D., & Thurik, R. (2007). The Effect of Business Regulations on Nascent and Young Business Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28, 171-186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9014-1 [ Links ]

Veblen, T. (1899). Teoría de la Clase Ociosa. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Volchek, D., Saarenketo, S., & Jantunen, A. (2015). Structural Model of Institutional Environment Influence on International Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. In S. Marinova (Ed.), Institutional Impacts on Firm Internationalization (pp. 190-216). UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Williams, N., & Williams, C. (2014). Beyond necessity versus opportunity entrepreneurship: some lessons from englis deprived urban neighbourhoods. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal (10), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0190-3 [ Links ]

Williamson, O. (1975). Las Instituciones económicas del capitalismo. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

World Bank. (2018). Ranking del estudio Doing Business en México. Doing Business. http://espanol.doingbusiness.org/Rankings/mexico/ [ Links ]

Zahra, S., & Garvis, D. (1996). International Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performance: The Moderating Effect of International Environmental Hostility. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 469-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00036-1 [ Links ]

Received: June 22, 2018; Accepted: January 21, 2019

texto en

texto en