Introduction

In Mexico, more than 1,800,000 people are dedicated to handicraft production or related to this craft (Sales, 2013); they are distributed among ten regions that produce ethnic textiles. Ethnic textiles are important because they represent an element of collective identity and help preserve the most important cultural and ethnographic heritage in Mexico. Furthermore, they constitute a business opportunity for both local and national development (Toledo-López, Mendoza-Ramírez & Sánchez-Medina, 2016), and are the livelihood of marginal communities where women support their families when male members migrate to the United States (Hernández, 2012). However, the handicraft sector faces a difficult situation because the product sales are low (Toledo-López, 2012).

Hernández, Domínguez and Mendoza (2010) and Toledo-López (2013) suggested that piracy was the cause of the handicrafts weak sales; also, the lack of differentiation in terms of designs and the use of modern products that have displaced handicrafts. Consequently, to fit the global market conditions, the crafts sector has been forced to increase production, making use of different sources of raw materials, implement new ways of commercialization and create changes in their designs (Hoyos, 2013). For example, some fashion designers work with ethnic textile craftsmen and create unique clothes with indigenous inspiration to compete in global markets (Castellanos, 2016).

Most artisans in their native communities operate in subsistence markets and direct their product to their equals, the consumers at the base of the pyramid (Toledo et al., 2016). For generations, they have focused on this market segment with utilitarian designs, such as “rebozos”, traditional costumes, and everyday clothing in the community, among others, which led to a dynamic of the low-income market due to the purchase frequency and product price, as well as an intense competition among local producers. As a result, profits have been sacrificed for price competition (Mendoza & Toledo, 2014)

Moreover, Karnani (2012) proposed that to reduce poverty among the producers at the base of the pyramid, they must create added value for their products to fulfill the market needs in the next level of the pyramid: the medium level. Also, ethnic textile producers could innovate and focus on a middle-class segment that might be willing to pay a higher price for a differentiated product (Toledo-López, 2013) and who could become potential customers for craft textiles. In Mexico, this consumer segment has an approximate size of 38 million people (DOF, 2014) and their purchasing power is rising (Dobbs, Remes, Manyika, Roxburgh, Smit & Schaer, 2012; Kravets & Sandikci, 2014). The middle-class consumer is on average 28.4 years-old (Boumphrey & Bevis, 2013) and has completed at least high school (INEGI, 2013); their average monthly income is above 652 dollars (Beteta, 2013) and provides 30% of the family’s income for discretional purchases of automobiles, home appliances, housing clothes, education, leisure and health (Cavusgil & Buckley, 2016). Additionally, the buyers in this market segment are socially responsible, when they acquire a product they look for environmental features such as energy efficiency, sustainability during manufacturing and minimal impact on the environment during use; they also expect the purchase will allow saving money to benefit the household finances (Boumphrey & Bevis, 2013).

Purchase intention has been studied extensively from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen (1991), which emphasizes the consumer’s attitude as a key variable to explain his behavior. Although recent studies describe a positive direct relation between purchase attitude and purchase intentions (Chen, 2013; Patrícia-Silva, Figueiredo, Hogg & Sottomayor, 2014; Cheah, Phau & Liang, 2015), this model does not address how the ethnic identity of consumers influences the purchase intention within a context of artisan products. Studies on purchasing behavior consider ethnical identity as a predictor to explain the attitude and purchase intention because it is related to the emotions and attitude of consumers who are proud of their ethnic origins (Ha-Brookshire & Norum, 2011). Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyze how the purchase attitude mediates the relation between ethnic identity and intention to purchase ethnic textiles. The results will provide information to help the crafts sector understand the middle-class consumer attitudes and their purchase intentions, so they can redirect their crafts towards a market segment that is growing and searching for innovative products. Moreover, they would be able to increase their sales, improve their product prices and create an added value for their crafts.

The article is structured as follows. First, a review of the literature on the middle-class consumer in Mexico and the purchase intention, and its relation to the variables behavioral attitude and ethnic identity is introduced to develop the hypotheses of study. Second, the methodology is described. Third, the results are presented. Fourth, the discussions and implications of the study are revised.

Literature review

The middle-class consumer in Mexico

The middle-class in Mexico is the fastest growing segment and comprises 14.6 million households that represent 47% of the total households in the country; it is expected to exceed 18 million households by 2030. More than 50% of middle-class households in Mexico, which consist of four members on average, have at least one-color TV, a refrigerator, a cell phone and a washing machine. A little less than half of the middle-class households own a car, a microwave oven, satellite television and internet (Boumphrey, 2015).

Within the income pyramid in Mexico, the middle-class has two classifications, the upper-middle-class and the lower-middle-class. The upper-middle-class in Mexico is characterized for having at least a baccalaureate degree, living in urban areas, having dual incomes, working in the formal economy and having a smaller family with fewer children than households with low income. This consumer prioritizes the expenditure of their household budget on goods and services in the following importance order: education (40%), clothing (39%), furniture and home decor (20%) and electronics 16%). Specifically, they prefer to spend their household expenses on buying, renovating, decorating or furnishing a home (83%), leisure and leisure travel (51%), car expenses (36%), or dining out (10%). Financial security is also important for the Mexican upper-middle-class consumers; thus, they look for quality products that offer good designs and are sold at the right price (Boumphrey, 2015). In addition, this consumer aspires to be a part of the upper class, accordingly, they identify and mimic their buying trends in shopping centers located abroad or malls, or acquiring clothes from international brands made by luxury designers.

On the other hand, the lower-middle-class in Mexico keep their level of ethnic identity because they are still in contact with the lower class of the income pyramid. These consumer values products that use raw materials and are not derived from endangered species, respect natural environments, are safe for the consumer’s health and participate in fair trade (Ocampo Perdomo-Ortiz & Castaño 2014). In addition, 40% of the lower-middle-class consumers expect that the characteristics of the responsible products will help them save money to protect their household finances. The 60% of the lower-middle-class consumers, being ethical and responsible consumers concerned for the environment and the marginalized populations, seek information on the origin and materials used to manufacture the products they buy, their environmental impact and the sustainable processes implemented in its elaboration (Boumphrey & Bevis, 2013). For this reason, the Mexican lower-middle-class could be considered the future market segment of buyers of ethnic textiles.

Purchase intention

Purchase intention is essential to understand the consumer behavior and is one of the most used indicators in marketing (Barden, 2014). The literature on studies about consumers’ purchasing behavior suggests that purchase intention explains the degree in which a person is willing to purchase a specific product (, Liang Chen, Duan & Ni, 2013; Chinomona, 2013).

This research analyzes ethnical identity and purchase attitude to explain purchase intentions regarding ethnic textiles in middle-class consumers in Mexico.

Purchase Attitude

Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) considered that attitude can predict purchase intentions, which can help explain a person’s behavior. Attitude can be defined as the degree of evaluation or favorable or non-favorable appraisal that the person does about his or herself, about others and about objects, when performing a specific behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Kim, Njite & Hancer, 2013; Vederhus, Zemore, Rise, Clausen & Høie, 2015). Moreover, it can be measured through semantical differentiation scales such as good-bad, beneficial-harmful, pleasurable, non-pleasurable (Ferdous & Polonsky, 2013); documentation of manifested behaviors such as the number of times that participants perform different activities (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001); participation in focus groups (Patricia-Silva et al., 2014); or questions on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 5=strongly agree to 1=strongly disagree (Mohd-Suki, 2014).

For Chen & Lee (2015), the characteristics of a product that results in a positive attitude towards products are quality and the materials used to manufacture them. Consumers acquire a positive purchase attitude based on the expectations, desires, and needs that they have regarding the properties and quality of the product. Therefore, the material’s quality and the traditional production methods (such as handmade) of the products are determinant to develop a positive purchase attitude in middle-class consumers. Nevertheless, the characteristics of the product by themselves cannot ensure that middle-class Mexican consumers search the product they desire in a local context since in emerging markets such as Mexico, foreign products are generally perceived as superior with regards to local products in terms of their attributes (Kinra, 2006). Thus, the idea that ethnic textiles have lower quality and value than products from contemporary brands jeopardizes establishing a cultural and ethnographic Mexican collective identity. For this reason, to analyze intention to purchase ethnic textiles it is essential to understand the degree of identification the middle-class consumers have towards ethnic textiles and the communities that produce them.

Ethnical identity

Ethnical identity can be defined as a complex psychological process of thoughts and feelings that a person possesses with regards to him/herself and about other people based on perception, cognition, affection, and knowledge (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Mansori, Sambasivan & Md-Sidin, 2015). Ethnical identity has a multidimensional character as a construct in which the components significantly and collectively contribute to the sense of belonging to ethnic collectives (Guitart. 2011; Guitart, Damián & Daniel, 2011). Several studies defined ethnical identity based on the displayed force, such as the affiliation intensity a person has towards a specific ethnic group (Ogden, Ogden & Schau, 2004; Makgosa, 2012); the level of dependence an individual has towards a specific ethnic group (Phinney, 1992); and, the attitudes and sense of belonging a person shows in relation to a specific ethnic group (Jamal & Chapman, 2000).

Furthermore, Phinney (1990) identified five initial components of ethnical identity: 1) ethnicity, which refers to a personal heritage and ethnical heritage of the parents or country of origin; 2) self-identification as a member of an ethnical group; 3) ethnical belonging, this is, the sense of belonging to a specific ethnic group; 4) ethnical involvement, this means the active participation as a member of an ethnical group; and 5) ethnical attitude that denotes an individual personal opinion regarding the ethnical group to which the person identifies. On the other hand, it is also assumed that ethnic identity is a multidimensional construct consisting of five components: 1) the cognitive component or ethnic self-identification, which refers to the description a person performs in itself based on ethnic labels; 2) the evaluation component related to the value an individual attaches to membership of an ethnic group; 3) the affective component of the emotional bond that the person has with the ethnic group; 4) the behavioral component, this is, the participatory attitude the individual has with respect to the cultural practices of the ethnic group; and 5) the development component of ethnic identity (Castro, 2002). Nevertheless, recent research (Sabatier, 2008; Dandy, Durkin, McEvoy, Barber & Houghton, 2008; Guitart et. al., 2011) suggests that there are two basic components of ethnical identity: the ethnic affirmation which refers to the description a person performs based on ethnic labels and the value an individual gives to his membership of a specific ethnic group, and the ethnic exploration described as the participatory attitude the individual has regarding cultural practices of the ethnic group. These studies used the Multigroup Ethnic Identity (MEIM) measurement scale by Phinney (1992) to measure ethnic identity. This scale includes 14 items to assess three aspects of ethnic identity, positive ethnic attitudes, and ethnicity; achievement of ethnic identity, which includes both exploration and problem-solving identity; and behavior or ethnic practices.

Hypothesis

Ethnical identity and purchase intention

Although the literature on intention to purchase ethnic textiles is scarce, some studies report that ethnical identity should be considered to explain purchase intention. In this regard, Webster (1994) concluded that Hispanic husbands who have a strong ethnic identity exert greater influence on purchasing decisions than their wives, while husbands and wives with weak ethnic identity exhibit joint purchase decisions. Weinberg and Berger (2011) pointed out that people who identified strongly with an ethnic group tend to look for ethnic features when they choose a product. Similarly, other authors found that ethnic identity significantly predicts the intention to consume and pay more for products made from organic materials (Ellis et al., 2012). Also, it was found that ethnic identity significantly predicts purchase intention and the willingness to pay more for products made with organic materials (Shen & Dickson., 2001; Ellis et al, 2012). In addition, identification of a consumer that recognizes cultural and emotional significance of a product of ethnic origin directly influences purchase intention towards ethnic clothing (Chattaraman & Lennon, 2008). Recent studies endorse the existence of a relationship between ethnic identity and purchase intention (Bartikowski, Taieb & Chandon, 2016; Fischer, & Zeugner-Roth, 2016; Yen, Wang, & Yang, 2017). Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. The ethnic identity of the Mexican middle-class consumers influences their purchase intention.

Ethnic Identity, attitude and purchase intention

The reviewed literature does not refer to the attitude of consumer behavior as a mediating variable between ethnic identity and purchase intention. However, research has found a positive and significant relationship between ethnic identity and purchase attitude, and purchase attitude and purchase intention. Laroche, Kim and Tomiuk (1998) found that ethnic identity influences attitudes towards consumption with cultural and ethnic significance of local products. Furthermore, Crane, Hamilton and Wilson (2004) reported that ethnic identity has a positive influence on the attitudes of Scottish consumers who use traditional costumes while residing in the United States and Canada. According to Vida, Dmitrovic and Obadia (2008), ethnic identity has a direct and positive impact on consumption of domestic products in consumers of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Similarly, Kim and Arthur (2003) concluded that Asian-Americans consumers who expressed pride in their ethnic identity also maintained a more positive attitude towards their country’s traditional costumes. Recent studies from Jensen y Limbu (2016), Yen et al. (2017), Jones, Reilly, Cox y Cole (2017), y Moriuchi y Jackson (2017), support the existence of a relation between purchase attitude and purchase intention.

At the same time, the literature reviewed confirms that a positive attitude encourages the purchase of organic clothing (Kang, Liu & Kim, 2013; Cowan & Kinley, 2014, Han & Chung, 2014) and the purchase intention of products with an ethnic origin. For example, Forney and Rabolt (1985-1986) found that consumers of seven ethnic groups in the San Francisco Bay, who had a high degree on the scale of ethnic identity, use and identify more with the use of clothing produced in a traditional way. Likewise, Kang et al. (2013) found that the attitudes of behavior in young consumers from South Korea, China, and the United States, modify the intention to purchase textiles and eco-friendly clothing. Besides, Cowan and Kinley (2014) reported that personal attitudes towards the environment of US consumers have an impact on purchase intentions of eco-friendly clothing. For Han and Chung (2014), the attitudes of female Korean consumers changed the intention to purchase clothes made with organic cotton. Recent studies indicate that there is a relation between purchase attitude and purchase intention (Hung, de Kok, & Verbeke, 2016; Ganesan, Sridhar, & Priyadharsani, 2016; Bong Ko, Bong Ko, Jin, & Jin, 2017). The research cited above points out that the ethnic identity determines the positive attitude of the consumer towards products elaborated with traditional techniques and organic material; similarly, this positive purchase attitude explains the purchase intention. The following mediation model illustrates the purchase intention from the ethnic identity and attitude of the consumer behavior perspective, and leads to the second hypothesis proposed:

H2. The purchase attitude mediates the relationship between ethnic identity and the intention to purchase ethnic textiles of the middle-class consumers in Mexico.

Method

Sample and data collection

This research was quantitative, exploratory and transversal. The middle-class in Mexico is classified as lower-middle-class and upper-middle-class (DOF, 2014). The lower-middle-class was chosen as the study population because they identify themselves as ethical consumers and responsible for fair trade products that come from native communities; also, they are interested in knowing the origin of the products they purchase and are considered as the next generation buyers of ethnic textiles in Mexico. The sample of future middle-class buyers were selected according to the following criteria: (1) consumers with incomes between 166 and 344 dollars a month per person, according to the INEGI (2013), the minimum household income middle-class is between 653 and 737 dollars a month; (2) level of education equal to graduate degree or higher (De la Calle & Rubio, 2010); (3) age between 20 and 29 years-old age corresponding to 23% of the economically active population in Mexico (INEGI, 2014); and, (4) having knowledge of the indigenous communities that produced ethnic textiles. Accordingly, postgraduate students in Mexico were selected, who for their age, education and knowledge, will become the next generation of the middle-class in Mexico once they join the work environment and will belong to the market segment of consumers with economic capacity who tend towards the purchase of ethnic and artisanal products from Mexican native populations. Furthermore, they were selected as the future consumers because they are concentrated in places with access to the data required to test the hypotheses of this study. Correspondingly, postgraduate students in Mexico who met the following criteria were selected from the sample: (1) have an income between $ 479 and $ 638 per month as part of a study grant from the National Quality Graduate Program (PNPC) Conacyt; (2) age between 24 and 30 years-old (3) have completed a bachelor’s and / or master’s degree; and, (4) they currently reside in one of the Mexican states with native communities that produce handcrafted textiles, which means they have information about the product origin, the materials they are made of and the producers of ethnic textiles from the state where they live.

From a list of 207 graduate programs that are in the PNPC Conacyt, we selected the five universities with the greatest amount of quality graduate programs in states of Mexico with greater representation of places where ethnic textiles are produced. The sampling site included the National Autonomous University of Chiapas (UNACH), the Interdisciplinary Center for Integral Research and Regional Development, Oaxaca’s Unit (CIIDIR Oaxaca) National Polytechnic Institute, the Autonomous University of Puebla (BUAP), the Veracruzana University (UV) and the Autonomous University of Yucatan (UADY).

The survey was applied to 405 postgraduate students, of which 63% studied at a master’s level and 37% studied at Ph.D. level. Regarding their location, 46.9% of the total were surveyed in the UV, 24.7% in the BUAP, 12.3% in the UADY, 8.6% in the UNACH and 7.4% in the CIIDIR Oaxaca. Concerning their profile, 50.6% of respondents were female and 49.4% male; 68.4% were single and 72.9% were between 24 and 31 years-old; also, 73.3% reported having worked before starting their postgraduate studies. With regards to clothing purchases, 67.1% spent 10% of their monthly income on clothes, while 83.5% went shopping for clothes 10 times in the last year. About ethnicity, 97.8% identified themselves as non-members to any ethnic group and 98.3% expressed they did not speak an indigenous language.

Operationalization of variables

Purchase intention was defined as the disposition and willingness of consumer to purchase ethnic textiles. Disposition was specified as for how frequent the consumer bought and recommended purchasing ethnic textiles. Willingness was set as the degree to which the consumer expressed their desire to purchase ethnic textiles. Several questions were established to measure the variable, such as: When you are buying clothing, how often do you purchase ethnic textiles? and how often do you purchase, give or recommend ethnic textiles to your relatives and friends? A Likert-type scale of 5 points was used in which 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = almost always 5 = always.

Ethnic identity was specified as the sense of ethnic affirmation and exploration the consumer had with their ethnic group. Ethnic affirmation was operatively defined as the emotional connection consumer had towards an ethnic group. To measure this dimension, a 5-point Likert-type scale was used in which 1 = None, 2 = A little, 3 = Fair, 4 =Much 5 = Too Much. Ethnic exploration was operatively defined as the frequency with which consumer investigates and participates in activities related to an ethnic group. To measure the variable, consumer was asked: To what extent do you feel a strong attachment to your ethnic group? and How often do you have dedicated time to find out more about your ethnic group? A Likert-type scale of 5 points was used in which, 1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Almost always, 5 = Always.

The purchase attitude was set as the degree to which the consumer evaluates a purchase of ethnic textiles as favorable when compared with a conventional garment from the perspective of the product, market and manufacturing. The product dimension was operationally defined as the consumer attitude toward the physical characteristics and the materials ethnic textiles are made from. The market was specified as the consumer attitude regarding distribution channels and places where ethnic textiles can be bought. Production was operationally defined as the attitude the consumer has over traditional techniques used to manufacture ethnic textiles. To measure the variable, consumer was asked: How favorably do you evaluate the purchase of ethnic textiles because they are of better quality than conventional garments have a fair price, and they are handmade? A 5-point Likert scale was used in which 1 = Not at all favorable, 2= Unfavorable, 3 = Fair, 4 = Favorable and 5 = Very favorable.

Results

Reliability and validity analysis

The internal validity of the scales was an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the maximum likelihood technique with Promax Rotation and Kaiser Normalization to reduce the dimensions. The items selected were factor loadings ≥0.5. For reliability using Cronbach’s alpha. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and the Bartlett sphericity were tested for sampling adequacy to determine the relevance of the factor analysis. There were six components labeled: disposition to purchase (Factor 1), willingness to purchase (Factor 2), attitude towards the production (Factor 3), attitude towards the product (Factor 4), ethnic affirmation (Factor 5) and ethnic exploration (Factor 6). The total variance explained was 68.285%, with a KMO of 0.921 and a Cronbach alpha of 0.945. The Bartlett test result was statistically significant (Chi-square=13124.50; p=0.000) (Table 1). The six components used to explain the research model proposed in this research were valid and reliable for the following inferential analyzes.

Table 1 Properties of the measurement model

| ID | Items | EFA load factor | Total variance explained | CFA standardized factor | CRa | AVEb |

| Disposition to purchase | 33.325 | 0.949 | 0.675 | |||

| ID11 go back to buy textiles frequently | 0.907 | 0.861 | ||||

| ID17 support the work of artisans | 0.850 | 0.846 | ||||

| ID13 recommend visiting artisan communities | 0.843 | 0.872 | ||||

| ID14 promote the purchase of ethnic textiles within my family | 0.840 | 0.895 | ||||

| ID10 I like to buy ethnic textiles | 0.818 | 0.839 | ||||

| ID12 visit artisans to buy an ethnic textile | 0.795 | 0.745 | ||||

| ID4 prefer ethnic textiles that come from artisanal communities | 0.776 | 0.716 | ||||

| ID2 choose ethnic textiles when I buy clothes | 0.731 | 0.710 | ||||

| Willingness to purchase | 7.237 | 0.918 | 0.617 | |||

| IV3 give away an ethnic textile frequently | 0.901 | 0.759 | ||||

| IV5 have the wish to buy an ethnic textile for my relatives | 0.900 | 0.780 | ||||

| IV6 have the wish to buy an ethnic textile for my friends | 0.861 | 0.711 | ||||

| IV4 have the wish to buy an ethnic textile for myself | 0.806 | 0.903 | ||||

| IV8 go back to buy ethnic textiles frequently | 0.748 | 0.888 | ||||

| IV2 visit artisans to buy ethnic textiles | 0.657 | 0.810 | ||||

| IV7 buy an ethnic textile for my classmates | 0.611 | 0.609 | ||||

| Attitude towards the production | 5.876 | 0.877 | 0.590 | |||

| APR4 ethnic textiles use traditional production techniques | 0.869 | 0.879 | ||||

| APR2 ethnic textiles help preserve the ethnic culture of the community | 0.806 | 0.758 | ||||

| APR3 ethnic textiles are made with traditional designs | 0.750 | 0.755 | ||||

| APR1 ethnic textiles stimulate the economy of local producers | 0.741 | 0.660 | ||||

| APR6 ethnic textiles are handmade | 0.708 | 0.772 | ||||

| Attitude towards the product | 3.48 | 0.848 | 0.653 | |||

| AP5 ethnic textiles have better quality than conventional garments | 0.884 | 0.870 | ||||

| AP6 ethnic textiles are more resistant than conventional garments | 0.839 | 0.859 | ||||

| AP7 ethnic textiles are more functional than conventional garments | 0.629 | 0.681 | ||||

| Ethnic affirmation | 14.557 | 0.954 | 0.724 | |||

| IEA3 feel a strong attachment to my ethnic group | 0.925 | 0.863 | ||||

| IEA8 I feel strongly linked to my ethnic group | 0.896 | 0.900 | ||||

| IEA1 have a strong sense of belonging to my ethnic group | 0.889 | 0.803 | ||||

| IEA2 understand what it means to belong to my ethnic group | 0.867 | 0.808 | ||||

| IEA7 understand the meaning of my ethnic background | 0.828 | 0.908 | ||||

| IEA9 I am aware of my ethnic roots | 0.786 | 0.871 | ||||

| IEA5 I feel good about my ethnic origin | 0.779 | 0.769 | ||||

| IEA4 feel very proud of my ethnic group | 0.768 | 0.876 | ||||

| Ethnic exploration | 3.809 | 0.903 | 0.654 | |||

| IEE2 participate in the cultural practices of my ethnic group | 0.876 | 0.847 | ||||

| IEE1 devote time to find out more about my ethnic group | 0.819 | 0.864 | ||||

| IEE3 talk to other people to learn more about my ethnic group | 0.801 | 0.906 | ||||

| IEE4 actively participate in social groups that include members of my ethnic group | 0.773 | 0.769 | ||||

| IEE5 think about how my life is affected by belonging to an ethnic group | 0.533 | 0.626 | ||||

| Total variance explained | 68.285 | |||||

| KMO | 0.921 | |||||

| Sig. Bartlett sphere. test | 0.000 | |||||

| Cronbach alpha | 0.945 |

a Composite reliability = (P standardized loading)2/ (P standardized loading)2 +P measurement error.

b Variance extracted =P (standardized loading)2/ P (standardized loading)2 +P measurement error.

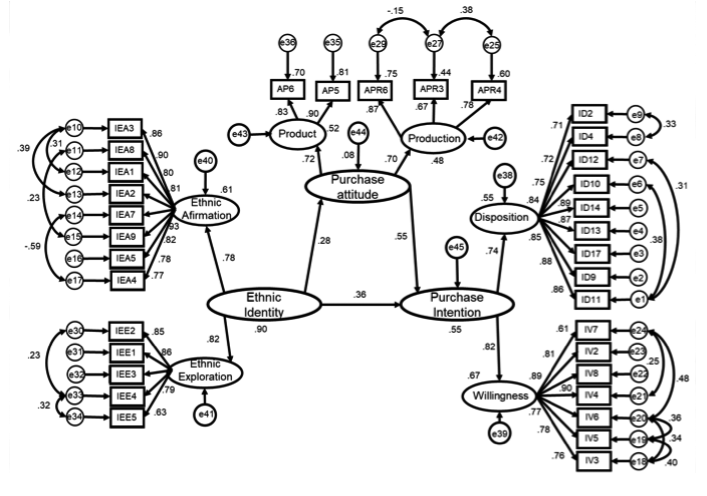

Furthermore, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on all scales with AMOS version 21 to confirm the structure obtained in the EFA using the maximum likelihood method. The CFA showed an appropriate model fit with a GFI of 0.870, which is considered within the traditional values as it tends to 1; and with better values (SRMR = 0.046, RMSEA = 0.049, CFI = 0.955) by the proposed parameters (SRMR <0.08, RMSEA <0.06, IFC> 0.95) by Hu and Bentler (1999). Additionally, the following acceptable parsimony indexes were found: a chi-square normalization (CMIN / DF) of 1.969 and a Parsimony Ratio (PRATIO) of 0.898. The CFA results showed that factorial loads of the dimensions were higher than 0.5 and statistically significant (Table 1).

Reliability was assessed using composite reliability (CR) whose value should be greater than 0.60 according to Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt (2011). All the constructs showed coefficients greater than 0.75. The square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct exceeded the reference point of 0.50 recommended by Hair et al. (2010), thus an adequate convergent validity was obtained. To assess their discriminant validity, the square root of the extracted mean-variance (AVE) for each latent variable was compared with the correlation coefficients for the other latent variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All the AVE (0.949, 0.954, 0.918, 0.877, 0.903, 0.848) were higher than the correlation coefficient of other variables (0.675, 0.724, 0.617, 0.590, 0.654, 0.653 respectively), with a favorable discriminant validity between each dimension in this study (Table 1).

Analysis of reliability and validity of the model

After, a second-order CFA was performed to integrate the components obtained into second-order constructs. A structure of three factors of second order (ethnic identity, purchase attitude and purchase intention) was obtained from 34 items; during the process, two questions of the attitude towards production component and one question of the attitude towards the product component were eliminated. The CFA showed a proper model fit with a GFI of 0.881, SRMR = 0.050, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.962, CMIN / DF = 1.922 and PRATIO = 0.893.

As shown in Table 2, the measurement model presented adequate indexes of reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity. Reliability was assessed by composite reliability (CR) which showed coefficients greater than 0.75 for all constructs. The AVE coefficients were higher than the correlation coefficient of other variables, thus there was a favorable discriminant validity between each dimension in this study. The second order CFA results showed that the factorial loads of the dimensions were all higher than 0.5 and statistically significant.

Table 2 Convergence reliability and validity - CFA

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | Ethnic identity | Purchase intention | Purchase attitude | |

| Ethnic identity | 0.833 | 0.714 | 0.264 | 0.857 | 0.845 | ||

| Purchase intention | 0.756 | 0.608 | 0.426 | 0.902 | 0.514 | 0.780 | |

| Purchase attitude | 0.668 | 0.502 | 0.426 | 0.918 | 0.280 | 0.653 | 0.709 |

Source: Author’s own

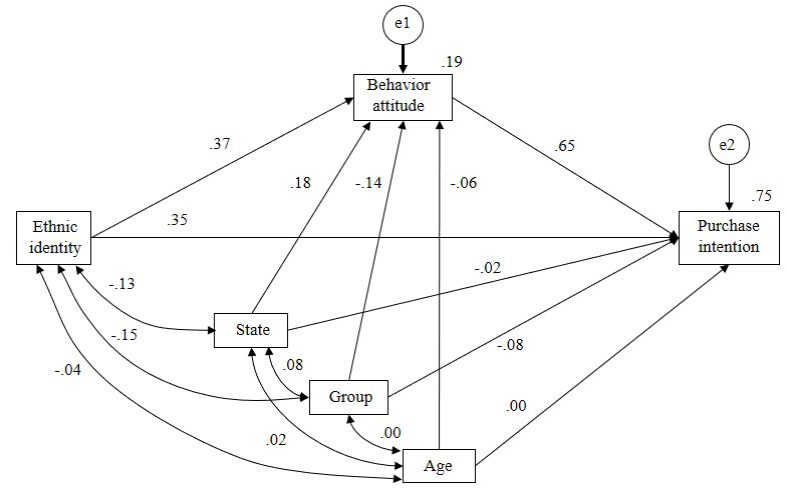

Test of the model and hypothesis

The structural equations model (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses. SEM was performed using the maximum likelihood estimation method. The structural model and hypotheses were analyzed by assessing the importance of the path coefficient and the variance explained for the study constructs (Figure 2). The model showed a proper fit with the data (GFI = 0.881, SRMR = 0.050, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.962, CMIN / DF = 1.922 and PRATIO = 0.893).

The path coefficient of the ethnic identity towards the purchase intention was 0.608 and was statistically significant (p = 0.001), which confirmed the H1: Ethnic identity influences the purchase intention of ethnic textiles in middle-class consumers in Mexico (Table 3).

Table 3 Results of the structural model

| Hypothesis | Direct without effect mediator | Direct with effect mediator | Indirect effect | Result |

| H1: Ethnic identity àPurchase intention | 0.608, p=0.001 | Proved | ||

| H2: Ethnic identity à Purchase attitude à Purchase intention | 0.608, p=0.001 | 0.301, p=0.001 | 0.214, p=0.001 | Partial mediation |

Source: Author’s own

To test H2, which proposed that behavioral attitude mediates the relationship between ethnic identity and intention to purchase ethnic textiles of the middle-class consumers, the indirect effect of ethnic identity was measured using the bootstrapping method proposed by Hayes (2009) and 2000 bootstrap samples were obtained by resampling. This method is more persuasive than the causal step approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). The presence of the behavioral attitude as a mediating variable between the ethnic identity and the purchase intention had a coefficient of 0.301 and was statistically significant (p = 0.001); an indirect effect coefficient of 0.214 was also significant (p = 0.001). Therefore, the mediation is partially proved (Table 3) because the coefficient of the direct effect of ethnic identity on the purchase intention without the presence of the attitude, is higher than the coefficient of the indirect effect between the ethnic identity and the purchase intention with the presence of the attitude as mediator (0.608, p = 0.001). Thus, hypothesis 2 is partially proved.

Moreover, to avoid the spurious effect of demographic variables, such as place of origin, age, and ethnic group of the consumer, the purchase intention model analyzed the influence of demographic variables State -which indicated if the interviewee came from a state producing ethnic textiles-, age and group, to measure as a control variable if the consumer belonged to an ethnic group and in that case, if this had an influence on the model. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 4, the demographic variable State (0.176, p = 0.001) is the only one that showed influence in the model as a control variable. Besides, neither age nor ethnic group membership was significant as control variables in the model.

Table 4 Regression model with the control variables

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

| Purchase attitude | <--- | State | 0.176 | 0.024 | 3.887 | *** |

| Purchase attitude | <--- | Group | -0.142 | 0.051 | -3.13 | 0.002 |

| Purchase attitude | <--- | Age | -0.064 | 0.02 | -1.419 | 0.156 |

| Purchase intention | <--- | State | -0.019 | 0.017 | -0.76 | 0.447 |

| Purchase intention | <--- | Group | -0.081 | 0.035 | -3.188 | 0.001 |

| Purchase intention | <--- | Age | -0.003 | 0.014 | -0.106 | 0.916 |

Source: Author’s own

Conclusions

The model obtained in our research shows that the purchase intention of ethnic textiles from the middle-class in Mexico is determined by their ethnic identity and purchasing attitude. However, the purchase attitude plays a mediating role in the relationship between ethnic identity and purchase intention. The Mexican middle-class consumer is willing and intends to buy an ethnic textile when their purchase attitude shifts from the conventional garment towards textiles. The attitude of the consumer is manifest when they evaluate positively the purchase of an ethnic textile and this change surfaces according to how much they identify with the ethnic group of the producer. Thus, the purchase attitude towards an ethnic textile modifies partially and significantly the relationship between ethnic identity and purchase intention.

Furthermore, the disposition and willingness of the middle-class consumer in Mexico to buy ethnic textiles are more meaningful when they feel emotionally connected to an ethnic group, and have information about the history, traditions and customs or participate directly in cultural and support activities of the ethnic group. These results coincide with Moore, Weinberg and Berger (2010) research on immigrant women, as they found that a person with a greater ethnic identity looks for ethnic attributes in a product they intend to purchase.

Additionally, the middle-class consumers in Mexico who identify and feel proud of belonging to an ethnic group, have a positive attitude about learning more about the cultural activities of the ethnic identification group. Therefore, the crafts that include designs and cultural symbols developed by the producers of 68 ethnic groups represent the identity of consumers in Mexico; this ethnic identity helps to increase the intention to purchase textiles. The consumers expressed their disposition and willingness to buy ethnic textiles for three main reasons. First, for the resistance, quality and functionality of textiles. Second, there is a social value given by the communities of origin, therefore consumers perceive that the purchase of textiles contributes directly to the economy of small producers and preserves the ethnic culture and traditional techniques of the communities. Third, consumers assign ethnic textiles an ecological value as they are made of organic and regional materials that do not damage the environment. This positive attitude of the middle-class consumers in Mexico towards ethnic products coincides with Moriuchi and Jackson (2017) research, which stated that consumers with strong ethnic identification show a positive attitude towards brands and products that refer to their ethnic origin, and that this positive attitude directly and significantly influences the intention to purchase.

Our research concluded that middle-class consumers in Mexico still identify and maintain a sense of belonging to Mexican ethnic textile groups, even though individuals in the middle-class do not participate directly in the activities of the ethnic group they belong to. This social class is characterized by their multiple occupations, such as work, academic, professional improvement, and family welfare. However, they show a great willingness to contribute to the preservation of the ethnic group culture, and maintain their emotional connection with the identification group by purchasing an ethnic textile that contributes directly to the economic income of the artisan’s families. Moreover, they participate in protecting the environment by choosing a product made from an organic raw material, and are aware that when they purchase an ethnic textile, they are also buying functional, resistant and quality garments. This research provides empirical evidence that in Mexico ethnic identity plays an important role in changing the attitude of consumers towards the purchase of products with ethnic attributes, which for their quality contribute significantly to society, the environment and the family economy of the consumers.

The middle-class is a large and growing market segment that possesses knowledge and information on the attributes of the ethnic product; its quality, social, cultural and environmental value, helps improve the economic income of local producers. Thus, we can conclude that this market segment could be the future consumers of ethnic products in Mexico, if the production and marketing of the items conserve the cultural, traditional, social and environmental characteristics and symbols. The middle-class consumers in Mexico show a strong intention towards the purchase of ethnic textiles. They also constitute a segment of potential buyers due to their emotional connection with ethnic groups and their knowledge and information on the origin and the materials with which the ethnic products are made, making them the preferred clothing. The middle-class prefers purchasing ethnic textiles because this social class is characterized by being ethical and responsible.

From these observations, we can say that the most information about the origin and production of ethnic products the middle-class has, the greater chance they will be the future buyers of ethnic textiles in Mexico. Empirically, this study shows that graduate students, who represent the middle-class, are willing to buy ethnic textiles if they receive information about the origin of the product, the environmentally friendly materials they used and the ethnic group that produced them. This contributes significantly to the marketing literature by extending the standard model of the TPB, as it provides evidence that ethnic identity plays an important role in explaining the intention to purchase an ethnic product. Moreover, ethnic identity modifies the purchase attitude towards ethnic products if they generate social, cultural and ecological benefits, and do not affect the economic income of consumers. The purchase attitude is a predictor variable of the purchase intention, but it also has a significant influence as a mediating variable when explaining the purchase intention of a product with ethnic attributes within the model of purchase intention with ethnic, ethical, socially and environmentally responsible consumers.

The model resulting from our research has consequences for the social and ecological practitioners, as well as for professional marketers. We propose a model of purchase intention of a product with an ethnic, social and ecological attributes, which is a model prior to purchasing behavior. The results aim to find and identify a potential market segment for products with ethnic attributes such as handicrafts in Mexico. These products are representative of the country and represent the identity and a source of income for the families of the communities of origin. In general, a marketing plan that attracts the attention of the middle-class niche market with a profile of an ethnic consumer, who is socially and environmentally responsible, will help to preserve the tradition, knowledge and hereditary cultural symbols for generations in Mexico. Increasing the purchasing behavior of products with ethnic attributes will favor the economy of the communities of ethnic origin; consequently, they will improve the family income of the producers and will contribute to the non-deterioration of the environment.

Implications

This study has both theoretical and practical implications. From an academic point of view, the results identified valid measures of ethnic identity and purchase attitude dimensions within the context of intention to purchase ethnic textiles. This research enriches current literature on how purchase attitude mediates the relationship between ethnical identity and intention to purchase ethnic textiles, offering a comprehensive profile of middle-class consumers in Mexico.

On the practical side, the study identified that the middle-class has knowledge about the cultural importance of ethnic textiles and have a positive attitude towards them; they intend to purchase them to support the financial improvement of the producer’s communities and protect the environment. Craftsmen should provide information on the cultural contents of their design, symbols and models, as well as on the quality, resistance, and functionality features of ethnic textiles so the middle-class consumers can purchase their products directly and not through intermediaries such as designers and stores; this would increase their sales and allow them to compete in the global market.

Moreover, the results provide artisanal producers with important information on the middle-class consumer’s segment, which could help them increase their participation and sales in this market. Considering that the middle-class consumer is academically prepared and has access to information, artisans must generate marketing strategies to provide information on the textile’s origin and its ethnic and cultural meaning, including the organic composition of the product materials to generate positive attitudes in this growing market segment; it is estimated that middle-class consumers will spend about 20 trillion dollars by 2025 (Dobbs et al., 2012; Kravets & Sandikci, 2014).

The study tested a marketing model to reorient marketing strategies for ethnic and artisanal products, which are currently sold to two segments of the income pyramid: through designers labeled as ethnical who direct their products to the upper class of the income pyramid; and through local markets targeting the low-income market segment on the base of the income pyramid. However, the middle-class segment of the income pyramid in Mexico is a growing potential market, whose members still maintain an ethnic identity and show a sense of belonging to ethnic groups, they are informed of what they are consuming and with a great sense of responsibility and commitment to the native populations, as well as with culture, traditions, environment and vulnerable groups. Consequently, this model should provide consumers in general, with or without ethnic identity, with information about the origin of the products, the materials used in the production and the benefits for the producer, to increase the purchase intention of artisanal products and in a future, attain a purchasing behavior that improves the economic income of artisans.

For future research, we recommended selecting a sample of consumers without a sense of belonging to an ethnic group and ethnic identity to show the influence of the purchase attitude when there is no ethnic identity. Also, to use a sample of consumers that live in a different location from where the ethnic and artisanal products are made to find the influence of behavioral attitude when there is no direct information about the origin and the materials and techniques used to produce craft products. Furthermore, members of the middle-class in Mexico should be selected without distinguishing between upper and lower-middle-class, as well as other types of consumers to validate the model with different consumers from the income pyramid.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)