INTRODUCTION

The marine otter, Lontra felina, is distributed along the South Pacific Ocean, from Peru (9°04ʹ S) to Cape Horn (56° S) in Chile, and in the southern tip of Argentina, on Isla de los Estados (54° S) (Castilla and Bahamondes 1979, Ostfeld et al. 1989, Sielfeld 1992, Parera 1996, Alfaro-Shigueto et al. 2011). This species occurs both in hydrographic environments of the Peruvian Andes (BMOD 1968, Hvidberg-Hansen 1970, AEDES 1998, Zeballos et al. 2002, Medina et al. 2018) and in marine environments (Estes 1986). On coastal shorelines, marine otters use a strip of 100-150 m offshore and 30 m on land (Castilla and Bahamondes 1979; Medina-Vogel et al. 2007, 2008).

Numerous studies have described behavioral aspects of marine otters on coastal shorelines with human presence (Medina-Vogel et al. 2007, 2008; Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009; Cursach et al. 2012). In these environments, the opportunistic behavior of marine otters allows them to coexist with non-hostile humans; in areas of high hostility, it shows the opposite pattern (Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009, Cursach et al. 2012). Despite its persistence in anthropic environments, the behavior and activity patterns of L. felina have been scarcely studied in coastal areas with human presence in Peru.

The marine otter is widely distributed on the Peruvian coast (Apaza and Romero 2012), where its presence and behavior depend on the intensity of human activities (Medina-Vogel et al. 2007, 2008; Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009). Currently, information on how anthropogenic disturbances, such as port activities and beach visits, influence the behavior of this predator is still limited. This issue impedes making effective decisions for the conservation of this carnivore, which is listed as endangered on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The aim of this study was to compare the diurnal behavior of the marine otter between 2 locations with different anthropic impact in the province of Islay in Arequipa, Peru.

Port activities influence marine otter behavior in the province of Islay. We expect more behavioral activity of marine otters to occur in localities with less influence of anthropic impact, that is, in natural environments where the impact is absent or minor, in contrast to localities with greater industrial port and fishing activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

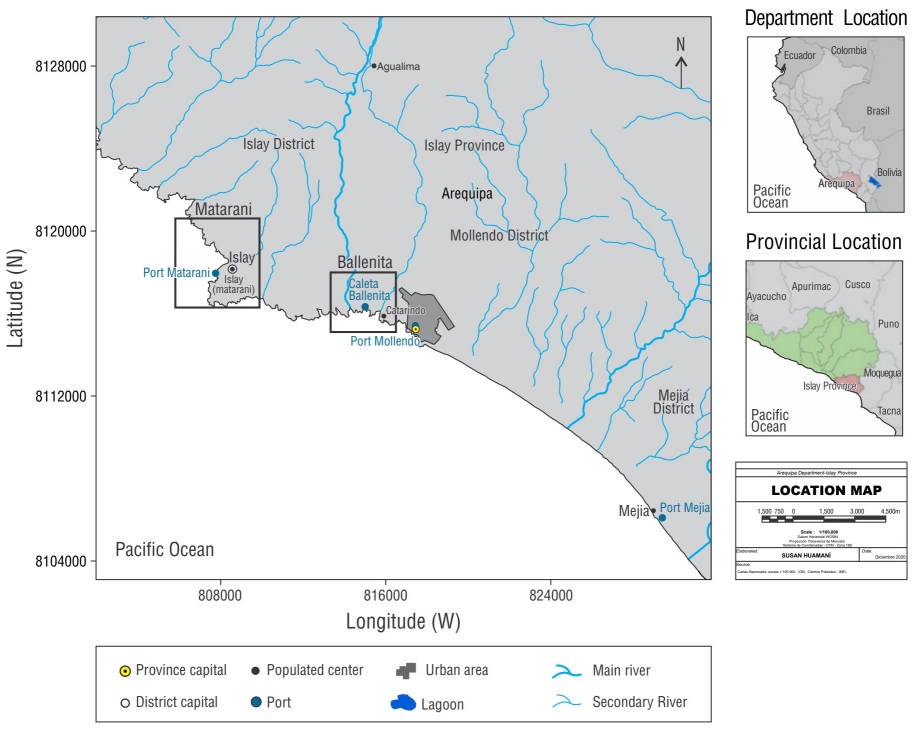

The study was carried out in 2 locations, Puerto Matarani 16°59ʹ59.39ʺ S, 72°6ʹ23.06ʺ W) and La Ballenita Bay (17°0ʹ56.32ʺ S, 72°2ʹ28.56ʺ W), politically located in the province of Islay, in the department of Arequipa, south of the Peruvian coast. Puerto Matarani comprises the Pesquero wharf and the Terminal Internacional del Sur wharf in the Islay district. La Ballenita comprises an islet and a beach surrounded by cliffs at both ends that is frequented by vacationers (Fig. 1).

Data collection

To record the largest number of behavioral activities of L. felina, the data were taken according to the ad libitum observation method (Altmann 1974). We observed the behavior of marine otters between February 1 and May 31, 2019, during the austral seasonal periods of summer and autumn. To avoid changes in the behavior of marine otters, we observed them from strategic locations (cliffs, rocks, and wharfs), ensuring a wide observation angle to differentiate 2 types of surfaces, aquatic and rocky, as habitat indicators (Villegas 2000). Observations occurred between 05:30 AM and 5:30 PM, and this time period was denominated an observation session. Each observation session was subdivided into 1-h intervals denominated observation events, with a maximum of 13 observation events per session. We counted marine otter sightings during each observation session as recommended by Badilla and George-Nascimento (2009). We performed sightings during 3 time slots: from 05:30 AM to 09:30 AM, from 09:30 AM to 1:30 PM, and from 1:30 PM to 5:30 PM. The occurrence of 6 types of behavior was timed and recorded: feeding, moving, diving, socializing, grooming, and resting. Feeding is the consumption of prey, and it is carried out in water and on rocks; marine otters hold prey on their chest with their forelimbs while floating in the water (Pizarro 2014). Moving is the most frequent behavior in marine otters in southern Peru, and it is considered as the movement from one place to another; pollution by mine tailings, intense artisanal fishing, and high concentration of human settlements cause individuals of L. felina to move in search of resources (Pizarro 2014). Grooming occurs once a day, usually on rocks, among seaweed, or in their burrows; grooming is the action of scratching against the rocks and the scratching of the neck with the hind limbs, in an assisted manner, with bites or licks (Pizarro 2014). Resting is the resting period when otters observe their surroundings for 5-18 s (Castilla and Bahamondes 1979).

We elaborated distribution maps of sightings in Puerto Matarani and in La Ballenita to spatially position marine otter sightings. In addition, we classified the presence/absence (1/0 records) of anthropic activities (fishing and port activities) delimiting a line parallel to the coast, established 50 m away and perpendicular to the observation site. We used this distance as a reference because marine otters use a range between 100-150 m offshore and 30 m on land (Castilla and Bahamondes 1979; Medina-Vogel et al. 2007, 2008). Finally, we divided the sightings into offshore and nearshore (50 m) using the previously established perpendicular distance to shore (Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009).

Data analysis

We used the χ 2 test to determine differences in sighting frequencies according to the type of surface (rock and water), the presence/absence of human activities, the type of behavior between study locations, and in diurnal activities according to the time slots (Greenwood and Nikulin 1996). We compared the diving behavior between both locations using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for 2 samples (Zar 1996). Finally, we evaluated whether there were differences in the presence or absence of anthropic activities using Fisher’s exact probability test.

RESULTS

Diurnal behavior

In total, we carried out 75 observation events, with 271 sightings and 12,405.4 s of activity. We carried out 52 observation events at Puerto Matarani, with 119 sightings and 6,721.8 s of activity, and 23 observation events at La Ballenita, with 152 sightings and 5,683.6 s of activity.

Moving was the most frequent type of behavior in Puerto Matarani, with 61.3% of the sightings and 39.8% of the time. This behavior was observed more frequently in water than on rocks. Of 73 sightings, 72.6% of the records corresponded to moving in water. Regarding diving, this behavioral category represented 28.6% of the records and was the second most performed activity. We timed 34 sightings at this locality; 3 showed animals with prey, and the average duration of diving was 68.2 s. On the other hand, the less frequent behaviors were feeding (1.7% of the sightings and 7.6% of the time) and grooming (1.7% of the sightings and 0.9% of the time; Tables 1, 2).

Table 1 Number of sightings of the behavioral categories of marine otters in Puerto Matarani and La Ballenita (Peru) in 2019.

| Behavioral category |

Puerto Matarani | La Ballenita | Total | |||||

| Water | Rock | Subtotal | Water | Rock | Subtotal | |||

| Feeding | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Moving | 53 | 20 | 73 | 37 | 33 | 70 | 143 | |

| Diving | 34 | - | 34 | 13 | - | 13 | 47 | |

| Socializing | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 8 | |

| Grooming | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 29 | 29 | 31 | |

| Resting | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 37 | |

| Total | 92 | 27 | 119 | 55 | 97 | 152 | 271 | |

Table 2 Duration (in seconds) of behavioral categories for the marine otter in Puerto Matarani and La Ballenita (Peru) in 2019.

| Behavioral category | Puerto Matarani | La Ballenita | Total | |||||

| Water | Rock | Subtotal | Water | Rock | Subtotal | |||

| Feeding | 49.0 | 465.0 | 514.0 | 18.0 | 282.0 | 300.0 | 814.0 | |

| Moving | 2,371.6 | 305.8 | 2,677.4 | 1,960.2 | 351.6 | 2,311.8 | 4,989.2 | |

| Diving | 2,317.4 | - | 2,317.4 | 1,438.8 | - | 1,438.8 | 3,756.2 | |

| Socializing | 811.0 | 0.0 | 811.0 | 334.0 | 0.0 | 334.0 | 1,145.0 | |

| Grooming | 0.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 643.0 | 643.0 | 703.0 | |

| Resting | 0.0 | 342.0 | 342.0 | 0.0 | 656.0 | 656.0 | 998.0 | |

| Total | 5,549.0 | 1,172.8 | 6,721.8 | 3,751.0 | 1,932.6 | 5,683.6 | 12,405.4 | |

Moving was the most frequent behavior in La Ballenita, with 46.1% of the sightings and 40.7% of the time. At this location, moving of marine otters was remarkably similar in both water and rocks (52.9% and 47.1%, respectively), followed by resting (21.7%) and grooming (19.1%). Diving represented 8.6% of the behavioral categories recorded; we observed the manipulation of prey only in 1 of these 13 sightings. The average duration of diving at this location was 110.7 s. The least frequent behavior was feeding (2.0% of sightings and 5.3% of the time; Tables 1, 2).

In Puerto Matarani, marine otters were sighted more frequently in the water (77.3% of the sightings and 82.5% of the time), whereas in La Ballenita they were sighted mostly on the rocks (63.8% of sightings and 34.0% of the time; χ 2 = 43.80, d.f. = 1, P < 0.001). The frequency of observations of different behavior types showed significant differences between locations (χ 2 = 52.60, d.f. = 5, P < 0.001). It was more frequent to observe marine otters moving and resting in La Ballenita and moving and diving in Puerto Matarani. The behavioral types feeding and socializing showed no significant differences between locations. In Matarani, moving was more frequent in water than on rocks (χ 2 = 5.16, d.f. = 1, P < 0.005), whereas in La Ballenita, there were no significant differences. Diving duration was significantly longer in Puerto Matarani (U = 295.5, P < 0.0001). Grooming and resting were only recorded in rocky environments at both locations.

In Puerto Matarani, the frequency of sightings of different types of behavior did not differ significantly in the 4 months evaluated (February-March: χ 2 = 3.65, d.f. = 5, P = 0.601; March-April: χ 2 = 2.90, d.f. = 5, P = 0.715; April-May: χ 2 = 6.15, d.f. = 5, P < 0.001). Regarding sighting frequency, from February to March moving increased by 44.2% and diving by 40.0%; between March and April, moving decreased by 51.2% and diving by 57.9%; and between April and May, moving increased, again, by 33.4% and diving by 28.6% (Fig. 2). In La Ballenita, the sighting frequency of the types of behavior differed. In February-March, no comparisons were made. We found significant differences (χ 2 = 9.284, d.f. = 5, P < 0.001) between April and May. Between February and March, the frequency of the behavior types moving, diving, and socializing decreased, with zero records of each. From March to April, moving and resting increased; between April and May, moving increased by 53.1%, diving by 81.8%, grooming by 93.1%, and resting by 81.8% (Fig. 3).

Figure 2 Frequencies of behavioral categories for the marine otter in Puerto Matarani (Peru) during February, March, April, and May 2019. ALI: feeding; TRA: transit; BUC: diving; SOC: socialization; ACI: grooming; and DES: rest.

Figure 3 Frequencies of behavioral categories for the marine otter in La Ballenita (Peru) during February, March, April, and May 2019. ALI: feeding, TRA: moving, BUC: diving, SOC: socializing, ACI: grooming, and DES: resting.

Sighting distribution according to the distance (nearshore/offshore) from the coast showed no significant differences (χ 2 = 0.56, d.f. = 1, P < 0.4439), although it was common to see marine otters near the coast in both locations (Table 3). At Puerto Matarani, we recorded more nearshore sightings in the presence of human activities (96.6%) than in their absence; however, there were no significant differences (Fisher’s exact probability test, P = 1). At La Ballenita, we recorded more sightings nearshore and in the absence of human activities (98.7%) than in their presence (Fisher’s exact probability test, P = 1).

Table 3 Records of marine otter sightings according to proximity/remoteness from the coast and presence (P)/absence (A) of human activities in the locations of Puerto Matarani and La Ballenita (Peru) in 2019.

| Location | Puerto Matarani | La Ballenita | Total | ||

| P | A | P | A | ||

| Near the coast | 106 | 4 | 2 | 143 | 255 |

| Far from the coast | 9 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 16 |

| Total | 115 | 4 | 2 | 150 | 271 |

Diurnal activity according to time slots

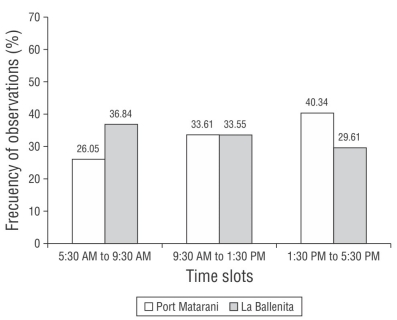

We found significant differences in the frequency of sightings between localities according to the time slots (χ 2 = 4.7, d.f. = 2, P < 0.001). At Puerto Matarani, the highest record of behavioral activity was between 1:30 PM and 5:30 PM, with 40.3% of the number of sightings and 73.2% of the time. At La Ballenita, the maximum value of behavioral activity occurred between 05:30 AM and 09:30 AM, with 36.8% of the records of sightings and 22.0% of the time (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

The diurnal behavior of marine otters described in this study indicates that this species persists in environments with different anthropic impacts, such as port activities and the presence of vacationers. At both locations, the behavior types observed were feeding, moving, diving, socializing, grooming, and resting. The frequency of occurrence of the behavior types moving and diving suggest that, in the study area, the marine otter could have a generalist and opportunistic behavior, which has been described in other localities of its geographic range (Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009, Cursach et al. 2012, Poblete et al. 2019).

It is possible that the greater number of sightings of marine otters moving and diving in the water in Puerto Matarani is related to the lower exposure to waves at this location, due to the presence of a breakwater and wharf, which also allows greater frequencies of socializing and resting times. Conversely, in La Ballenita, the greater exposure to waves could explain the similar frequencies of moving on land and moving in water and the consequent longer resting and grooming times. This phenomenon was described in northern Chile (Villegas et al. 2007), where an opposite pattern was observed on the central coast (Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009). Nevertheless, it is important to consider that other environmental factors, such as the availability of resources, the presence of human activities, or differences in productivity, are also associated with this behavior (Villegas et al. 2007, Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009). We suggest that our hypothesis regarding the influence of exposure to waves be tested in future studies to determine, under a quantitative approach, how differences in wave energy are associated with the movement of this marine mustelid.

Regarding the behavioral variations during the sampling period, we assumed the possibility that the presence of similar behavioral patterns during the months of study in Puerto Matarani could be related to the fishing activities in this location. Here, fishing residues could be a constant resource for marine otters, which alters their behavior. On the other hand, the different patterns of behavior recorded at La Ballenita can be explained by the fluctuations in human presence in this location. For example, between the months of February and March, the constant presence of vacationers and their associated impacts, such as noise and solid and organic waste, and the presence of stray dogs, alter the quality of the habitat for marine otters, which explains the absence of records of marine otters in that period of time. We suggest that this inference be interpreted with caution because it is possible that other factors not considered in this study could explain the differences between both locations. In general, variations in the time dedicated to various behaviors may be mediated by the presence of competitors, the breeding season, or environmental fluctuations at different times of the year (Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009).

Another important aspect to consider is the greater presence of marine otters near the coast at both locations. However, in Puerto Matarani, the presence of the otter was observed in the presence of humans, whereas in La Ballenita, the coast was used in the absence of humans. Otters exhibited the ability to take advantage of fishing residues (Cursach et al. 2012), which could explain their greater occurrence in Puerto Matarani, whereas the presence of vacationers would not offer usable waste for the otters; moreover, invasive activities of vacationers and their pets may promote the perception of increased threat in marine otters (Badilla and George Nascimento 2009). Numerous studies suggest that, although the marine otter can persist in environments with human presence, its response to different human activities depends on how hostile they are (Medina-Vogel et al. 2007, 2008; Badilla and George-Nascimento 2009; Cursach et al. 2012).

Regarding diurnal activity patterns, our results diverge between both study locations. According to the sightings, otters showed more activity starting at midday in Puerto Matarani (location with the presence of fishing residues), which agrees with the results in Badilla and George-Nascimento (2009). On the other hand, the peak of marine otter activity during mornings at La Ballenita can be explained by the reduced human activity during this time slot. A factor that reinforces this hypothesis was the absence of vacationers at La Ballenita during May, when the marine otter returned to its habitat at La Ballenita and increased its activities.

The results we show in this study are the first approximation to understanding diurnal behavior of the marine otter in the province of Islay, where human activities exert different impacts on the biodiversity associated with this marine coast. Medina-Vogel et al. (2008) suggest that anthropogenic development on coastal shores may increase the disturbance to the habitat of this predator, due to air and water pollution, presence of noise, presence of stray dogs, artificial lighting, and competition for resources. Given this, it is essential to determine how this predator responds to increasingly prevalent disturbances. This will make it possible to provide plausible recommendations to decision makers to effectively conserve marine otters. Data from this research can serve as a basis for future conservation and research efforts in the study area and other locations at different latitudes.

texto en

texto en